Difference between revisions of "Noah Webster"

V-Federici (talk | contribs) m |

V-Federici (talk | contribs) m (→Images) |

||

| Line 868: | Line 868: | ||

==Images== | ==Images== | ||

<gallery widths="170px" heights="170px" perrow="7"> | <gallery widths="170px" heights="170px" perrow="7"> | ||

| + | |||

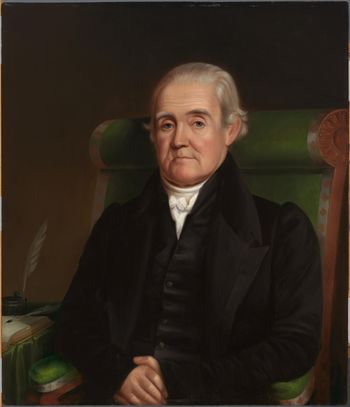

| + | File:2189.jpg|Samuel Finley Breese Morse, ''Portrait of Noah Webster'', [1823]. | ||

File:2285.jpg|James Herring, Noah Webster, 1833. | File:2285.jpg|James Herring, Noah Webster, 1833. | ||

Revision as of 10:33, April 8, 2021

Noah Webster (October 16, 1758–May 28, 1843), a lexicographer, editor, political writer, and author, made important contributions to the articulation of a distinctive national culture in post-Revolutionary America. He is best known as the creator of the first comprehensive American dictionary, which documented many of the differences between American and British usage of the English language.

History

Following an unsatisfactory early education, Noah Webster studied Latin and Greek privately and, at the age of fifteen, entered Yale College, where he came under the influence of Ezra Stiles and Timothy Dwight. He went on to study law and teach school before turning his attention to writing a series of newspaper articles promoting the American Revolution and urging a permanent separation from Britain. After founding a private school in Goshen, New York, he produced a three-volume compendium, A Grammatical Institute of the English Language, consisting of a speller (1783), a grammar (1784), and a reader (1785).[1] These works provided alternatives to imported English textbooks and established a uniquely American approach to teaching children how to read, spell, and pronounce words. Webster’s speller was the most popular American book of its time, with 15 million copies sold by 1837.[2] In 1787 Webster founded the American Magazine with the intention of promoting an American cultural identity distinct from that of Britain.[3]

Proceeds from the speller funded Webster’s work on a dictionary through which he intended to promote an American language with its own idioms, pronunciation, and style. In 1806 Webster published A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language, the first truly American dictionary. He immediately began work on a more ambitious work, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828). His research on word origins necessitated learning twenty-eight languages, including Anglo-Saxon, Aramaic, Russian, and Sanskrit.[4] Webster also documented unique American words that had not yet appeared in British dictionaries. Comprising 70,000 words—12,000 of which had never been published before—the American Dictionary surpassed the scope and authority of Samuel Johnson’s magisterial Dictionary of the English Language, published in London in 1755.[5] Although British examples predominate, Webster also referred to the American context for words such as avenue (“A wide street, as in Washington, Columbia”) (view text); differentiated American usage from British in the case of words such as meadow, orchard, plantation, and wood; and included quotations from American authors who imbued the English language with New World associations, as in the phrase attributed to Washington Irving, “The tremendous cataracts of America thundering in their solitudes [sic]” (view text). Despite his monumental achievement, Webster made little money from his dictionary and he went deeply into debt in order to finance a revised and expanded second edition, which was published in 1841, two years before his death.

—Robyn Asleson

Texts

An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828)

Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, vol. 1 (New York: S. Converse, 1828)[6]

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1: n.p.)

- “AL'LEY, n. al'ly [Fr. allée, a passage, from aller to go; Ir. alladh. Literally, a passing or going.]

- “1. A walk in a garden; a narrow passage.

- “2. A narrow passage or way in a city, as distinct from a public street.

- “3. A place in London where stocks are bought and sold. Ash.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1: n.p.)

- “ARBOR, n. [The French express the sense by berceau, a cradle, an arbor, or bower; Sp. emparrade, from parra, a vine raised on stakes, and nailed to a wall. Qu. L. arbor, a tree, and the primary sense.]

- “1. A frame of lattice work, covered with vines, branches of trees or other plants, for shade; a bower.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1: n.p.)

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1: n.p.)

- “ARCH, n. [See Arc.] A segment or part of a circle. A concave or hollow structure of stone or brick, supported by its own curve. It may be constructed of wood, and supported by the mechanism of the work. This species of structure is much used in bridges.

- “A vault is properly a broad arch. Encyc.

- “3. Any curvature, in form of an arch.

- “4. The vault of heaven, or sky. Shak.

- “Triumphal arches are magnificent structures at the entrance of cities, erected to adorn a triumph and perpetuate the memory of the event.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1: n.p.)

- “AV'ENUE, n. [Fr. from venir, to come or go; L. venio.]

- “1. A passage; a way or opening for entrance into a place; any opening or passage by which a thing is or may be introduced.

- “2. An alley, or walk in a garden, planted with trees, and leading to a house, gate, wood, &c., and generally terminated by some distant object. The trees may be in rows on the sides, or, according to the more modern practice, in clumps at some distance from each other. Encyc.

- “3. A wide street, as in Washington, Columbia.”

- back up to History

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1: n.p.)

- “A'VIARY, n. [L. aviarium, from avis, a fowl.]

- “A bird cage; an inclosure for keeping birds confined. Wotton.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1: n.p.)

- “BAS'IN, n. básn. [Fr. bassin; Ir. baisin; Arm. baçzin; It. bacino, or bacile; Port. bacia. . .]

- “1. A hollow vessel or dish, to hold water for washing, and for various other uses.

- “2. In hydraulics, any reservoir of water.

- “3. That which resembles a basin in containing water, as a pond, a dock for ships, a hollow place for liquids, or an inclosed part of water, forming a broad space within a strait or narrow entrance; a little bay.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1: n.p.)

- “B`ATH, n. [Sax. baeth, batho, a bath; bathian, to bathe; W. badh, or baz; D. G. Sw. Dan. bad, a bath; Ir. bath, the sea; Old Phrygian bedu, water. Qu. W. bozi, to immerse.]

- “1. A place for bathing; a convenient vat or receptacle of water for persons to plunge or wash their bodies in. Baths are warm or tepid, hot or cold, more generally called warm and cold. They are also natural or artificial. Natural baths are those which consist of spring water, either hot or cold, which is often impregnated with iron, and called chalybeate, or with sulphur, carbonic acid, and other mineral qualities. These waters are often very efficacious in scorbutic, bilious, dyspeptic and other complaints.

- “2. A place in which heat is applied to a body immersed in some substance. Thus,

- “A dry bath is made of hot sand, ashes, salt, or other matter, for the purpose of applying heat to a body immersed in them.

- “A vapor bath is formed by filling an apartment with hot steam or vapor, in which the body sweats copiously, as in Russia; or the term is used, for the application of hot steam to a diseased part of the body. Encyc. Tooke.

- “A metalline bath is water impregnated with iron or other metallic substance, and applied to a diseased part. Encyc. . .

- “3. A house for bathing. In some eastern countries, baths are very magnificent edifices.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1: n.p.)

- “BED, n. [Sax. bed; D. bed; G. bett or beet; Goth. badi. The sense is a lay or spread, from laying or setting.] . . .

- “4. A plat or level piece of ground in a garden, usually a little raised above the adjoining ground. Bacon.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1: n.p.)

- “BEE'-GARDEN, n. [bee and garden.] A garden, or inclosure to set bee-hives in. Johnson. . .”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1: n.p.)

- “BEL'VIDERE, n. [L. bellus, fine, and video, to see.] . . .

- “2. In Italian architecture, a pavilion on the top of an edifice; an artificial eminence in a garden. Encyc.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1: n.p.)

- “BORD'ER, n. [Fr. bord; Arm. id; Sp. bordo; Port. borda; It. bordo. See Board.]

- “The exterior part of a garden, and hence a bank raised at the side of a garden, for the cultivation of flowers, and a row of plants.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1: n.p.)

- “BOTAN'IC, BOTAN'ICAL, a. [See Botany.] Pertaining to botany; relating to plants in general; also, containing plants, as a botanic garden.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1: n.p.)

- “BOW'ER, n. [Sax. bur, a chamber or private apartment, a hut, a cottage; W. bwr, an inclosure.]

- “1. A shelter or covered place in a garden, made with boughs of trees bent and twined together. It differs from arbor in that it may be round or square, whereas an arbor is long and arched. Milton. Encyc.

- “2. A bed-chamber; any room in a house except the hall. Spencer. Mason.

- “3. A country seat; a cottage. Shenston., B. Johnson.

- “4. A shady recess; a plantation for shade. W. Brown. . .

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1: n.p.)

- “BOWLING-GREEN, n. [bowl and green.]

- “A level piece of ground kept smooth for bowling.

- “2. In gardening, a parterre in a grove, laid with fine turf, with compartments of divers figures, with dwarf trees and other decorations. It may be used for bowling; but the French and Italians have such greens for ornament. Encyc."

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1: n.p.)

- “BRIDGE, n. [Sax. bric, brieg, brigg, or brye, bryeg; Dan. broe; Sw. bryggia, bro; D. brug; Ger. brücke; Prus. brigge.]

- “1. Any structure of wood, stone, brick, or iron, raised over a river, pond, or lake, for the passage of men and other animals. Among rude nations, bridges are sometimes formed of other materials; and sometimes they are formed of boats, or logs of wood lying on the water, fastened together, covered with planks, and called floating bridges. A bridge over a marsh is made of logs or other materials laid upon the surface of the earth. . . Encyc.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1: n.p.)

- “CANAL', n. [L. canalis, a channel or kennel; these being the same word differently written; Fr. canal; Arm. can, or canol; Sp. Port. canal; It. canale. See. Cane. It denotes a passage, from shooting, or passing.]

- “1. A passage for water; a water course; properly, a long trench or excavation in the earth for conducting water, and confining it to narrow limits; but the term may be applied to other water courses. It is chiefly applied to artificial cuts or passages for water, used for transportation; whereas channel is applicable to a natural water course.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1: n.p.)

- “CASCA'DE, n. [Fr. cascade; Sp. cascada; It. cascata, from cascare, to fall.]

- “A waterfall; a steep fall or flowing of water over a precipice, in a river or natural stream; or an artificial fall in a garden. The word is applied to falls that are less than a cataract. . . .”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1: n.p.)

- “CAT'ARACT, n. [L. cataracta; . . . ]

- “1. A great fall of water over a precipice; as that of Niagara, of the Rhine, Danube and Nile. It is a cascade up on a great scale.

- “The tremendous cataracts of America thundering in their solitudes. Irving. . .”

- back up to History

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1: n.p.)

- “CLUMP, n. [Ger. klump; D. klomp; Sw. klimp; Dan. klump, a lump; W. clamp. It is lump with a prefix. It coincides with plump, and L. plumbum, lead; as the D. lood, G. loth, Dan. lod., Eng. lead, coincide with clod. It signifies a mass or collection. . .]

- “1. A thick, short piece of wood, or other solid substance; a shapeless mass. Hence clumper, a clot or clod.

- “2. A cluster of trees or shrubs; formerly written plump. In some parts of England, it is an adjective signifying lazy, unhandy. Bailey."

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1: n.p.)

- “COL'UMN, n. col'um. [L. columna, columen; W. colov, a stalk or stem, a prop; colovyn, Arm. coulouenn; Fr. colonne; It. colonna; Sp. columna; Port. columna or coluna. This word is from the Celtic, signifying the stem of a tree, such stems being the first columns used. The primary sense is a shoot, or that which is set.]

- “1. In architecture, a long round body of wood or stone, used to support or adorn a building, composed of a base, a shaft and a capital. The shaft tapers from the base, in imitation of the stem of a tree. There are five kinds or orders of columns. 1. The Tuscan, rude, simple and massy; the highth [sic] of which is fourteen semidiameters or modules, and the diminution at the top from one sixth to one eighth of inferior diameter. 2. The Doric, which is next in strength to the Tuscan, has a robust, masculine aspect; its highth [sic] is sixteen modules. 3. The Ionic is more slender than the Tuscan and Doric; its highth [sic] is eighteen modules. 4. The Corinthian is more delicate in its form and proportions, and enriched with ornaments; its highth [sic] should be twenty modules. 5. The Composite is a species of the Corinthian, and of the same highth [sic]. Encyc.

- “In strictness, the shaft of a column consists of one entire piece; but it is often composed of different pieces, so united, as to have the appearance of one entire piece. It differs in this respect from a pillar, which primarily signifies a pile, composed of small pieces. But the two things are unfortunately confounded; and a column consisting of a single piece of timber is absurdly called a pillar or pile.

- “2. An erect or elevated structure resembling a column in architecture; as the astronomical column at Paris, a kind of hollow tower with a spiral ascent to the top; gnomonic column, a cylinder on which the hour of the day is indicated by the shadow of a style; military column, among the Romans; triumphal column; &c.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1: n.p.)

- “COP'PICE, COPSE, n. [Norm. coupiz, from couper, to cut, Gr. . . .]

- “A wood of small growth, or consisting of underwood or brushwood; a wood cut at certain times for fuel.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1: n.p.)

- “DOVE-COT, n. A small building or box in which domestic pigeons breed. . .

- “DOVE-HOUSE, n. A house or shelter for doves. . .

- “PIG'EON, n. . .

- “The domestic pigeon breeds in a box, often attached to a building, called a dovecot or pigeon-house. The wild pigeon builds a nest on a tree in the forest.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1: n.p.)

- “EDG'ING, n. That which is added on the border, or which forms the edge; as lace, fringe, trimming, added to a garment for ornament. . .

- “2. A narrow lace.

- “3. In gardening, a row of small plants set along, the border of a flower-bed; as an edging of box. Encyc.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1: n.p.)

- “EM'INENCE, EM'INENCY, n. [L. eminentia, from eminens, emineo, to stand or show itself above; e and minor, to threaten, that is, to stand or push forward. . . .]

- “1. Elevation, highth [sic], in a literal sense; but usually, a rising ground; a hill of moderate elevation above the adjacent ground.

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1: n.p.)

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1: n.p.)

- “FOUNT', FOUNT'AIN, n. [L. fons; Fr. fontaine; Sp. fuente, It. fonte, fontana; W. fynnon, a fountain or source; fyniaw, fynu, to produce, to generate, to abound; fwn, a source, breath, puff; fwnt, produce.]

- “1. A spring, or source of water; properly, a spring or issuing of water from the earth. This word accords in sense with well, in our mother tongue; but we now distinguish them, applying fountain to a natural spring of water, and well to an artificial pit of water, issuing from the interior of the earth.

- “2. A small basin of springing water. Taylor.

- “3. A jet; a spouting of water; an artificial spring. Bacon.

- “4. The head or source of a river. Dryden.

- “5. Original; first principle or cause; the source of any thing.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1: n.p.)

- “GATE, n. [Sax. gate, geat; Ir. greata; Scot. gait; The Goth. gatwo, Dan. gade, Sw. gata, G. gasse, Sans. gaut, is a way or street. In D. gat is a gap or channel. . .]

- “1. A large door which gives entrance into a walled city, a castle, a temple, palace or other large edifice. It differs from door chiefly in being larger. Gate signifies both the opening or passage, and the frame of boards, planks or timber which closes the passage.

- “2. A frame of timber which opens or closes a passage into any court, garden or other inclosed ground; also, the passage.

- “3. The frame which shuts or stops the passage of water through a dam into a flume.

- “4. An avenue; an opening; a way. Knolles.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1: n.p.)

- “GREEN, n. The color of growing plants. . . .

- “2. A grassy plain or plat; a piece of ground covered with verdant herbage.

- “O'er the smooth enameled green. Milton.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1: n.p.)

- “GROT, GROT'TO, n. [Fr. grotte, It. grotta, Sp. and Port. gruta; G. and Dan. grotte; D. grot; Sax. grut. Grotta is not used.]

- “1. A large cave or den; a subterraneous cavern, and primarily, a natural cave or rent in the earth, or such as is formed by a current of water, or an earthquake. Pope. Prior. Dryden.

- “2. A cave for coolness and refreshment.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1: n.p.)

- “GROVE, n. [Sax. groef, graf, a grave, a cave, a grove; Goth. groba; from cutting an avenue, or from the resemblance of an avenue to a channel.]

- “1. In gardening, a small wood or cluster of trees with a shaded avenue, or a wood impervious to the rays of the sun. A grove is either open or close; open, when consisting of large trees whose branches shade the ground below; close, when consisting of trees and underwood, which defend the avenues from the rays of the sun and from violent winds. Encyc.

- “2. A wood of small extent. In America, the word is applied to a wood of natural growth in the field, as well as to planted trees in a garden, but only to a wood of small extent and not to a forest.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1: n.p.)

- “HEDGE, n. hej. [Sax. hege, heag, hoeg, hegge; G. heck, D. heg, haag; Dan. hekke or hek; Sw. hagn, hedge, protection; Fr. haie; W. cae. Hence Eng. haw, and Hague in Holland. . . .]

- “Properly, a thicket of thorn-bushes or other shrubs or small trees; but appropriately, such a thicket planted round a field to fence it, or in rows, to separate the parts of a garden.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1: n.p.)

- “HER'MITAGE, n. The habitation of a hermit; a house or hut with its appendages, in a solitary place, where a hermit dwells. Milton.

- “2. The cell in a recluse place, but annexed to an abbey. Encyc.

- “3. A kind of wine.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1: n.p.)

- “ICEHOUSE, n. [ice and house.] A repository for the preservation of ice during warm weather; a pit with a drain for conveying off the water of the ice when dissolved, and usually covered with a roof.”

Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, vol. 2 (New York: S. Converse, 1828)[7]

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “LAB'YRINTH, n. [L. labyrinthus. . .]

- “1. Among the ancients, an edifice or place full of intricacies, or formed with winding passages, which rendered it difficult to find the way from the interior to the entrance. The most remarkable of these edifices mentioned, are the Egyptian and the Cretan labyrinths. Encyc. Lempriere.

- “2. A maze; an inexplicable difficulty.

- “3. Formerly, an ornamental maze or wilderness in gardens. Spenser.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “LAKE, n. [G. lache, a puddle; Fr. lac; L. lacus; Sp. It. lago; Sax. luh; Scot. loch; Ir. lough; Ice. laugh. A lake is a stand of water, from the root of lay. Hence L. lagena, Eng. flagon, and Sp. laguna, lagoon.]

- “1. A large and extensive collection of water contained in a cavity or hollow of the earth. It differs from a pond in size, the latter being a collection of small extent; but sometimes a collection of water is called a pond or a lake indifferently.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “LAWN, n. [W. llan, an open, clear place. It is the same word as land, with an appropriate signification, and coincides with plain, planus, Ir. cluain.]

- “Betwixt them lawns or level downs, and flocks

- “Grazing the tender herbs, were interspers'd. Milton.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “MEAD, MEADOW, n. meed, med’o. [Sax. moede, moedewe; G. matte, a mat, and a meadow; Ir. madh. The sense is extended or flat depressed land. It is supposed that this word enters into the name Mediolanum, now Milan, in Italy; that is, mead-land.]

- “A tract of low land. In America, the word is applied particularly to the low ground on the banks of rivers, consisting of a rich mold or an alluvial soil, whether grass land, pasture, tillage, or wood land; as the meadows on the banks of the Connecticut. The word with us does not necessarily imply wet land. This species of land is called, in the western states, bottoms, or bottom land. The word is also used for other low or flat lands, particularly lands appropriated to the culture of grass.

- “The word is said to be applied in Great Britain to land somewhat watery, but covered with grass. Johnson.

- “Meadow means pasture or grass land, annually mown for hay; but more particularly, land too moist for cattle to graze on in winter, without spoiling the sward. Encyc. Cyc.

- “[Mead is used chiefly in poetry.]"

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “MOUND, n. [Sax. mund; W. mwnt, from mwn; L. mons. See Mount.]

- “Something raised as a defense or fortification, usually a bank of earth or stone; a bulwark; a rampart or fence.

- “God has thrown

- “That mountain as his garden mound, high raised. Milton.

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “MOUNT, n. [Fr. mont; Sax. munt; It. Port. Sp. monte; Arm. menez, mene; W. munt, a mount, mountain or mound, a heap; L. mons, literally a heap or an elevation. Ir. moin or muine; Basque, mendia. . .]

- “1. A mass of earth, or earth and rock, rising considerably above the common surface of the surrounding land. Mount is used for an eminence or elevation of earth, indefinite in highth [sic] or size, and may be a hillock, hill or mountain. We apply it to Mount Blanc, in Switzerland, to Mount Tom and Mount Holyoke, in Massachusetts, and it is applied in Scripture to the small hillocks on which sacrifice was offered, as well as to Mount Sinai. Jacob offered sacrifice on the mount or heap of stones raised for a witness between him and Laban. Gen. xxxi.

- “2. A mound; a bulwark for offense or defense.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “NURS'ERY, n. . .

- “2. A place where young trees are propagated for the purpose of being transplanted; a plantation of young trees. Bacon.

- “3. The place where anything is fostered and the growth promoted.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “OB'ELISK, n. [L. obeliscus; Gr. . . .]

- “1. A truncated, quadrangular and slender pyramid intended as an ornament, and often charged with inscriptions or hieroglyphics. Some ancient obelisks appear to have been erected in honor of distinguished persons or their achievements. Ptolemy Philadelphus raised one of 88 cubits high in honor of Arsinee. Augustus erected one in the Campus Martius at Rome, which served to mark the hours on a horizontal dial drawn on the pavement. Encyc.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “OR'CHARD, n. [Sax. ortgeard; Goth. aurtigards; Dan. urtegaard; Sw. ortegard; that is, wort-yard, a yard for herbs. The Germans call it baumgarten, tree-garden, and the Dutch boomgaard, tree-yard. See Yard.]

- “An inclosure for fruit trees. In Great Britain, a department of the garden appropriated to fruit trees of all kinds, but chiefly to apples trees. In America, any piece of land set with apple trees, is called an orchard; and orchards are usually cultivated land, being either grounds for mowing or tillage. In some parts of the country, a piece of ground planted with peach trees is called a peach-orchard. But in most cases, I believe the orchard in both countries is distinct from the garden.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “P`ARK, n. [Sax. parruc, pearruc; Scot. parrok; W. parc; Fr. id.; It. parco; Sp. parque; Ir. pairc; G. Sw. park; D. perk. . . .]

- “A large piece of ground inclosed and privileged for wild beasts of chase, in England, by the king’s grant or by prescription. To constitute a park, three things are required; a royal grant or license; inclosure by pales, a wall or hedge; and beasts of chase, as deer, &c. Encyc.

- “Park of artillery, or artillery park, a place in the rear of both lines of an army for encamping the artillery, which is formed in lines, the guns in front, the ammunition-wagons behind the guns. . . Encyc. . .

- “Park of provisions, the place where the sutlers pitch their tents and sell provisions, and that where the bread wagons are stationed.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “PAVILION, n. pavil’yun [Fr. pavillon; Sp. pabellon; Port. pavilham; Arm. pavihon; W. pabell; It. paviglione and padiglione; L. papilio; a butterfly, and a pavilion. According to Owen, the Welsh pabell signifies a moving habitation.]

- “1. A tent; a temporary movable habitation.

- “2. In architecture, a kind of turret or building, usually insulated and contained under a single roof; sometimes square and sometimes in the form of a dome. Sometimes a pavilion is a projecting part in the front of a building; sometimes it flanks a corner. Encyc.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “PIAZ'ZA, n. [It. for plazza; Sp. plaza; Port. praça, for plaça; Fr. place; Eng. id.; D. plaats; G. platz; Dan. plads; Sw. plats.]

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “PLANTA'TION, n. [L. plantatio, from planto, to plant.]

- “1. The act of planting or setting in the earth for growth.

- “2. The place planted; applied to ground planted with trees, as an orchard or the like. Addison.

- “3. In the United States and the West Indies, a cultivated estate; a farm. In the United States, this word is applied to an estate, a tract of land occupied and cultivated, in those states only where the labor is performed by slaves, and where the land is more or less appropriated to the culture of tobacco, rice, indigo and cotton, that is, from Maryland to Georgia inclusive, on the Atlantic, and in the western states where the land is appropriated to the same articles or to the culture of the sugar cane. From Maryland, northward and eastward, estates in land are called farms.

- “4. An original settlement in a new country; a town or village planted. . .

- “5. A colony.

- “6. A first planting; introduction; establishment; as the plantation of Christianity in England. K. Charles.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “PLEAS'URE-GROUND, n. Ground laid out in an ornamental manner and appropriated to pleasure or amusement. Graves.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “GARDEN-PLOT, n. The plot or plantation of a garden. Milton. . .

- “PLOT, n. [a different orthography of plat.]

- “2. A plantation laid out. Sidney.

- “3. A plan or scheme. . . Spenser.

- “4. In surveying, a plan or draught of a field, farm or manor surveyed and delineated on paper.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “POND, n. [Sp. Port. It. pantano, a pool of stagnant water, also in Sp. hinderance, obstacle, difficulty. The name imports standing water, from setting or confining. It may be allied to L. pono; Sax. pyndan, to pound, to pen, to restrain, and L. pontus, the sea, may be of the same family.]

- “1. A body of stagnant water without an outlet, larger than a puddle, and smaller than a lake; or a like body of water with a small outlet. In the United States, we give this name to collections of water in the interior country, which are fed by springs, and from which issues a small stream. These ponds are often a mile or two or even more in length, and the current issuing from them is used to drive the wheels of mills and furnaces.

- “2. A collection of water raised in a river by a dam, for the purpose of propelling mill-wheels. These artificial ponds are called mill-ponds.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “PORCH, n. [Fr. porche, from L. porticus, from porta, a gate, entrance or passage, or from portus, a shelter.]

- “1. In architecture, a kind of vestibule supported by columns at the entrance of temples, halls, churches or other buildings. Encyc.

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “PORTICO, n. [It. portico; L. porticus, from porta or portus.]

- “In architecture, a kind of gallery on the ground, or a piazza encompassed with arches supported by columns; a covered walk. The roof is sometimes flat; sometimes vaulted. Encyc.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “POT, n. [Fr. pot; Arm. pod; Ir. pota; Sw. potta; Dan. potte; W. pot, a pot, and potel, a bottle; poten, a pudding, the paunch, something bulging; D. pot; a pot, a stake, a hoard; potten, to hoard.]

- “1. A vessel more deep than broad, made of earth, or iron or other metal, used for several domestic purposes; as an iron pot, for boiling meat or vegetables; a pot for holding liquors; a cup, as a pot of ale; and earthern pot for plants, called a flower pot, &c.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “PROMENA'DE, n. [Fr. from promener; pro and mener, to lead.]

- “1. A walk for amusement or exercise.

- “2. A place for walking.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “PROS'PECT, n. [L. prospectus, prospicio, to look forward; pro and specio, to see.]

- “1. View of things within the reach of the eye.

- “Eden and all the coast in prospect lay. Milton.

- “2. View of things to come; intellectual sight; expectation. . .

- “3. That which is presented to the eye; the place and the objects seen. There is a noble prospect from the dome of the state house in Boston, a prospect diversified with land and water, and every thing that can please the eye.

- “4. Object of view.

- “Man to himself

- “Is a large prospect. Denham.

- “5. View delineated or painted; picturesque representation of a landscape. Reynolds.

- “6. Place which affords an extended view. Milton.

- “7. Position of the front of a building; as a prospect towards the south or north. Ezek. xl.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “QUARTER, n. quort'er. [Fr. quart, quartier; It. quartiere; Sp. quartel; D. kwartier; G. quartier; Sw. quart, quartal; Dan. quart, quartal, quarteer; L. quartus, the fourth part; from W. cwar, a square.] . . .

- “6. A particular region of a town, city or country; as all quarters of the city; in every quarter of the country or of the continent. Hence,

- “7. Usually in the plural, quarters, the place of lodging or temporary residence; appropriately, the place where officers and soldiers lodge, but applied to the lodgings of any temporary resident. He called on the general at his quarters; the place furnished good winter quarters for the troops. I saw the stranger at his quarters.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “ROCK'-WORK, n. Stones fixed in mortar in imitation of the asperities of rocks, forming a wall.

- “2. A natural wall of rock. Addison.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “RUST'IC, RUST'ICAL, a. [L. rusticus, from rus, the country.]

- “1. Pertaining to the country; rural; as the rustic gods of antiquity. Encyc.

- “2. Rude; unpolished; rough; awkward; as rustic manners or behavior.

- “3. Coarse; plain; simple; as rustic entertainment; rustic dress.

- “4. Simple; artless; unadorned. Pope.

- “Rustic work, in a building, is when the stones, &c. in the face of it, are hacked or pecked so as to be rough. Encyc. . .

- “RUSTIC, n. An inhabitant of the country; a clown.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “SEAT, n. [It. sedia; Sp. sede, sitio, from L. sedes, situs; Sw. sate; Dan. soede; G. sitz; D. zetel, zitplaats; W. sez; Ir. saidh; W. with a prefix, gosod, whence gosodi, to set. See Set and Sit. . .]

- “1. That on which one sits. . .

- “3. Mansion; residence; dwelling; abode; as Italy the seat of empire. The Greeks sent colonies to seek a new seat in Gaul.

- “In Alba he shall fix his royal seat. Dryden.

- “4. Site; situation. The seat of Eden has never been incontrovertibly ascertained. . .

- “8. The place where a thing is settled or established. London is the seat of business and opulence. So we say, the seat of the muses, the seat of arts, the seat of commerce.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “SHRUB'BERY, n. Shrubs in general.

- “2. A plantation of shrubs.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “SQUARE, n. . .

- “2. An area of four sides, with houses on each side.

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “STAT'UE, n. [L. statua; statuo, to set; that which is set or fixed.]

- “An image; a solid substance formed by carving into the likeness of a whole living being; as a statue of Hercules or of a lion.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “SUM'MER-HOUSE, n. 1. A house or apartment in a garden to be used in summer. Pope, Watts.

- “2. A house for summer’s residence.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “SUN'DIAL, n. [sun and dial], An instrument to show the time of day, by means of the shadow of a gnomon or style on a plate. Locke.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “TEM'PLE, n. [Fr.; L. templum; It. tempio; Sp. templo; W. temyl, temple, that is extended, a seat; temlu, for form a seat, expanse or temple; Gaelic, teampul.]

- “1. A public edifice erected in honor of some deity. Among pagans, a building erected to some pretended deity, and in which the people assembled to worship.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “TREILLAGE, n. trel'lage. [Fr. from treillis, trellis.]

- “In gardening, a sort of rail-work, consisting of light posts and rails for supporting espaliers, and sometimes for wall trees. Cyc. . .

- “TREL'LIS, n. [Fr. treillis, grated work.] In gardening, a structure or frame of cross-barred work, or lattice work, used like the treillage for supporting plants.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “VASE, n. [Fr. from L. vas, vasa, a vessel; It. vaso.]

- “2. An ancient vessel dug out of the ground or from rubbish, and kept as a curiosity.

- “3. In architecture, an ornament of sculpture, placed on socles or pedestals, representing the vessels of the ancients, as incense-pots, flower-pots, &c. They usually crown or finish facades or frontispieces. Cyc.

- “4. The body of the Corinthian and Composite capital; called also the tambor or drum.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “VERAN'DA, n. An oriental word denoting a kind of open portico, formed by extending a sloping roof beyond the main building. Todd.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “2. The whole extent seen. . .

- “3. Sight; power of seeing, or limit of sight. . .

- “4. Intellectual or mental sight. . . .

- “5. Act of seeing. . .

- “6. Sight; eye. . .

- “7. Survey; inspection; . . .

- “9. Appearance; show. . .

- “10. Display; . . .

- “11. Prospect of interest.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “GRAV'EL-WALK, n. A walk or alley covered with gravel, which makes a hard and dry bottom; used in gardens and malls. . .

- “WALK, n. wauk. The act of walking; the act of moving on the feet with a slow pace.

- “2. The act of walking for air or exercise; as a morning walk; an evening walk. Pope.

- “4. Length of way or circuit through which one walks; or a place for walking; as a long walk; a short walk. The gardens of the Tuilerie and of the Luxemburgh are very pleasant walks.

- “5. An avenue set with trees. Milton.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “WALL, n. [L. vallum; Sax. weal; D. wal; Ir. Gaelic, balla and fal; Russ. val; W. gwal. In L. vallus is a stake or post, and probably vallum was originally a fence of stakes, a palisade or stockade; the first rude fortification of uncivilized men. The primary sense of vallus is a shoot, or that which is set, and the latter may be the sense of wall, whether it is from vallus, or from some other root.].

- “1. A work or structure of stone, brick or other materials, raised to some highth [sic], and intended for a defense or security. Walls of stone, with or without cement, are much used in America for fences on farms; walls are laid as the foundation of houses and the security of cellars. Walls of stone or brick from the exterior of buildings, and they are often raised round cities and forts as a defense against enemies.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “WATERFALL, n. [water and fall.] A fall or perpendicular descent of the water of a river or stream, or a descent nearly perpendicular; a cascade; a cataract. But the word is generally used of the fall of a small river or rivulet. It is particularly used to express a cascade in a garden, or an artificial descent of water, designed as an ornament. Cyc.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “WIL'DERNESS, n. [from wild.] A desert; a tract of land or region uncultivated and uninhabited by human beings, whether a forest or a wide barren plain. In the United States, it is applied only to a forest. In Scripture, it is applied frequently to the deserts of Arabia. The Israelites wandered in the wilderness forty years.

- “2. The ocean. . .

- “3. A state of disorder. . .

- “4. A wood in a garden, resembling a forest.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “WOOD, n. [Sax. wuda, wudu; D. woud; W. gwyz.]

- “1. A large and thick collection of trees; a forest.”

- 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2: n.p.)

- “YARD, n. [Sax. geard, gerd, gyrd, a rod, that is, a shoot.] . . .

- “2. [Sax. gyrdan, to inclose; Dan. gierde, a hedge, an inclosure; gierder, to hedge in, Sw. garda.] An inclosure; usually, a small inclosed place in front of or around a house or barn. The yard in front of a house is called a court, and sometimes a court-yard. In the United States, a small yard is fenced round a barn for confining cattle, and called barn-yard, or cow-yard.”

An American Dictionary of the English Language (1848)

Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language. . . Revised and Enlarged by Chauncey A. Goodrich. . . (Springfield, MA: George and Charles Merriam, 1848)[8]

- 1848, An American Dictionary of the English Language. . . Revised and Enlarged (p. 32)

- “AL'COVE, AL-COVE, n. [Sp. alcoba, composed of al, with the Ar. . . . kabba, to arch, to construct with an arch, and its derivatives, an arch, a rounded house; Eng. cubby.] . . .

- “3. A covered building, or recess, in a garden.

- “4. A recess in a grove.”

- 1848, An American Dictionary of the English Language. . . Revised and Enlarged (p. 65)

- “ARBORETUM, n. A place in a park, nursery, &C, in which a collection of trees, consisting of one of each kind, is cultivated. Brande.”

- 1848, An American Dictionary of the English Language. . . Revised and Enlarged (p. 363)

- “DOVE'-COT, (duv’-kot,) n. A small building or box, raised to a considerable hight [sic] above the ground, in which domestic pigeons breed.”

- 1848, An American Dictionary of the English Language . . . Revised and Enlarged (p. 776)

- “OR'AN-GER-Y, n. [Fr. orangerie.]

- “A place for raising oranges; a plantation of orange-trees.”

- 1848, An American Dictionary of the English Language. . . Revised and Enlarged (p. 806)

- “PAVILION, n. pavil'yun [Fr. pavillon; Sp. pabellon; Port. pavilham; Arm. pavihon; W. pabell; It. paviglione and padiglione; L. papilio; a butterfly, and a pavilion. According to Owen, the Welsh pabell signifies a moving habitation.]

- “1. A tent; a temporary movable habitation.

- “2. In architecture, a kind of turret or building, . . . Gwilt.

- “The name is sometimes, though improperly, given to a summer-house in a garden. Brande.”

- 1848, An American Dictionary of the English Language. . . Revised and Enlarged (p. 824)

- “PIAZ'ZA, n. [It. for plazza; Sp. plaza; Port. praça, for plaça; Fr. place; Eng. id.; D. plaats; G. platz; Dan. plads; Sw. plats.]

- “2. In Italian, it denotes a square open space surrounded by buildings. Gwilt.”

- 1848, An American Dictionary of the English Language. . . Revised and Enlarged (p. 848)

- “POR'TI-CO, n. [It. portico; L. porticus, from porta or portus.]

- “In architecture, originally, a colonnade or covered ambulatory; but at present, a covered space, inclosed by columns at the entrance of a building. P. Cyc.”

- 1848, An American Dictionary of the English Language. . . Revised and Enlarged (p. 961)

- “ROCK'-WORK, (-wurk,) n. 1. Stones fixed in mortar in imitation of the asperities of rocks, forming a wall.

- “2. In gardening, a pile of stones or rocks, . . . for growing plants adapted for such a situation. P. Cyc.”

- 1848, An American Dictionary of the English Language. . . Revised and Enlarged (p. 972)

- “RUST'IC, RUST'ICAL, a. [L. rusticus, from rus, the country.]. . .

- “5. In architecture, a term denoting a species of masonry, the joints of which are worked with grooves, or channels, to render them conspicuous. The surface of the work is sometimes left or purposely made rough, and sometimes even or smooth. Gloss. of Archit.”

- 1848, An American Dictionary of the English Language. . . Revised and Enlarged (p. 1139)

- “TER'RACE, n. [Fr. terrasse; It. terrazzo; Sp. terrado; from L. terra, the earth.]

- “1. A raised level space or platform of earth, supported on one or more sides by a wall or bank of turf, &c., used either for cultivation or for a promenade.

- “2. A balcony or open gallery. Johnson.

- “3. The flat roof of a house.”

An American Dictionary of the English Language (1850)

Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language (Springfield, MA: George and Charles Merriam, 1850)[9]

- 1850, An American Dictionary of the English Language (p. 252)

- “CON-SERV'A-TO-RY, n. A place for preserving any thing in a state desired, as from loss, decay, waste, or injury. . .

- “2. A greenhouse for exotics, often attached to a dwelling-house as an ornament. In large conservatories, properly so called, the plants are reared on the free soil, and not in pots. Brande.”

- 1850, An American Dictionary of the English Language (p. 409)

- “ES-PAL'IER, (es-pal’yer,) n. [Fr. espalier; Sp. espalera; H. spalliera; from L. palus, a stake or pole.]

- “1. A row of trees planted about a garden or in hedges, so as to inclose quarters or separate parts, and trained up to a lattice of wood-work, or fastened to stakes, forming a close hedge or shelter to protect plants against injuries from wind or weather. Ency.

- “2. A lattice-work of wood, on which to train fruit-trees and ornamental shrubs. Brande.”

- 1850, An American Dictionary of the English Language (p. 1239)

- “VIS'TA, n. [It., sight; from L. visus, video.]

- “A view or prospect through an avenue, as between rows of trees; hence, the trees or other things that form the avenue.

- “The finished garden to the view

Other Resources

Library of Congress Name Authority File

Dictionary of National Biography

Noah Webster House and West Hartford Historical Society

Images

Notes

- ↑ David Micklethwait, Noah Webster and the American Dictionary (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2005), 21–22, 54–73, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Catherine Reef, Education and Learning in America (New York: Infobase Publishing, 2009), 22, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Edward E. Chielens, “Periodicals and the Development of an American Literature,” in Making America, Making American Literature, ed. A. Robert Lee and W. M. Verhoeven (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1996), 95–96, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Joshua Kendall, The Forgotten Founding Father: Noah Webster’s Obsession and the Creation of an American Culture (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 2010), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Joshua Lawrence Eason, “Dictionary-Making in the English Language,” Peabody Journal of Education 5 (May 1928): 349, view on Zotero; Joseph W. Reed Jr., “Noah Webster’s Debt to Samuel Johnson,” American Speech 37 (1962): 95–105, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), vol. 1, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), vol. 2 view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language. . . Revised and Enlarged by Chauncey A. Goodrich. . . (Springfield, MA: George and Charles Merriam, 1848), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language (Springfield, MA: George and Charles Merriam, 1850), view on Zotero.