Statue

History

British treatises available in North America frequently mentioned the statue as an ornament and set forth varied typologies. Batty Langley (1728), for example, categorized statues according to their arrangement and use in gardens (view text), whereas Isaac Ware (1756) used size to make distinctions (view text). Many statues in antebellum America were made of ephemeral materials, most notably wood, and, in some cases, painted plaster. In America, high-quality stone was not readily available for carving, and large metal casting was not popular until mid-century; as a result, before 1852 many statues were imported.[1] Treatise author Antoine-Joseph Dezallier d’Argenville commented in 1712 that “statues are not for every man, but princes and great ministers,” suggesting that decorum and propriety regarding class and status governed the use of statues and may have discouraged their use in the colonial period.[2] In addition, “statue” was not the only term used to refer to, in Noah Webster's 1828 words, “a solid substance formed by carving into the likeness of a whole living being” (view text). Other terms, such as “figure,” “sculpture,” “bust,” and “image,” were used with some frequency. Thomas Jefferson (1771), for example, described “a sleeping figure reclined on a plain marble slab, surrounded with turf” for his garden.[3]

Accounts of statues in the 18th century, such as those by Ezra Stiles (1754) and Daniel Fisher (1755) written with respect to the garden of Bush Hill, near Philadelphia, suggest that they ranged widely in quality. Stiles, on the one hand, claimed that the statues were exceptional—“in fine Italian marble curiously wrot” (view text); while Fisher, on the other, stated that the statues were merely ordinary (view text). Visitors’ garden descriptions indicate that statuary was often perceived to be worthy of mention, particularly when it was made of fine materials or when it illustrated significant themes. Philip Vickers Fithian, when extolling in 1774 the virtues of Mount Airy in Virginia, noted “four large beautiful Marble Statues” (view text). Charles Drayton, recounting in 1806 the “beauties of landscape” at The Woodlands, near Philadelphia, noted a “fine statue” that was included in portraits of the house (view text). Hannah Callender Sansom, writing in 1762, called attention to the statues of mythological subjects at Judge William Peters's estate, Belmont, near Philadelphia (view text). Classical themes for garden statuary frequently were recommended throughout the 18th and 19th centuries by treatise writers such as John James, Batty Langley, William Marshall, and G. Gregory.

Charles Willson Peale cut figures out of wooden board to resemble “statues in sculpture,” for his garden at Belfield (c. 1825) (view text). Elias Hasket Derby commissioned a group of four wooden “figures” from woodcarvers John Skillin and Simeon Skillin Jr. On September 25, 1793, the Skillin brothers presented Derby with a bill for “free standing figures of larger dimensions, ranging between 4 and 5 feet in height,” at a cost of approximately £7.10 each and .15 for priming. These statues were pastoral in theme and included a shepherdess, a gardener, and the figure of Plenty [Fig. 1]. The Skillins’s garden statuary resembled, both in handling and form, little figures on furniture, such as secretaries and chests, which were also carved by the brothers.[4]

One of the most elaborate and widely known displays of statues in 18th-century private gardens was that of Lord Timothy Dexter, who made a large fortune in the shoe business and in stock speculation. At his large house in Newburyport, Massachusetts, Dexter improved his garden by erecting a row of columns along the outer border of his front lawn. On the top of these columns he placed “colossal images carved in wood,” including figures of “Indian chiefs, military generals, philosophers, politicians and statesmen, now and then a goddess of Fame, or Liberty. . . [and] four lions” [See Fig. 11]. Dexter’s master carver Joseph Wilson (1779–1857) made approximately forty slightly less-than-life-size figures, which were occasionally repainted if a change in identity was desired.[5]

As a sketch (c. 1849) by Lewis Miller illustrates, statues were frequently incorporated into fountains [Fig. 2]. For the public fountain erected at Centre Square in Philadelphia [See Fig. 12], sculptor William Rush (1756–1833) provided a wooden female figure loosely based on classical statues. This work was reproduced many times in plaster casts and in prints. In an advertisement in the Philadelphia Gazette, and Daily Advertiser on July 20, 1820, Rush defended his choice of wood on the basis of economy and practicality.[6] The fountain figure, entitled Allegory of the Schuylkill River (or Water Nymph and Bittern), was moved to Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park in about 1829. Frances Milton Trollope described the striking effect of white painted wood against the dark rock Rush had amassed for the base. In both sites, the statue functioned as a visual focus for the designed landscape.

Statues were located throughout the garden or landscape. At the Moreau House in Morrisville, Pennsylvania, a classically inspired statue dominated the garden [Fig. 3]. At Belvedere in Baltimore, statues were interspersed with urns on the lawn [Fig. 4]. At Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts, they were placed on top of monuments or memorials [see Fig. 14]. At the Elias Hasket Derby House in Salem, Massachusetts, the extant sculpture Plenty was situated in front of a summerhouse, while the Gardener and the Shepherdess were positioned on the roof of a summerhouse designed by Samuel McIntire [Fig. 5]. At Fairmount Park, another William Rush statue, Mercury, was placed on top of a garden structure overlooking the river [Fig. 6]. Lemon Hill in Philadelphia was known for its collection of garden statues, including, as Benjamin L. C. Wailes noted on December 29, 1829, “a dog of natural size carved out of marble [who] sits just within the entrance [of the grotto],the guardian of the place.”[7]

Statues were used by garden designers to bring a focal point to the layout and to divert the eye. At Belmont, statues were placed in the center of the labyrinth, according to Hannah Callender Sansom. Statues often were placed on the lawn in front of the main façade of the house, as they were at The Woodlands, creating visual and physical ties between the ornamental style of the house and the garden scenery, as advised by British writer Thomas Whately (1770). Likewise, at Iranistan, in Bridgeport, Connecticut, statues on pedestals flanked the flower beds located near the grand entrance staircase [Fig. 7]. In other cases, statues were placed along the terrace, where they helped to articulate the divide between house and ornamented landscape. Charles Lyell in 1846 related this use of statues at country houses in Natchez, Mississippi. At Point Breeze, ancient statues overlooked the terrace and distant landscape [Fig. 8].

In public gardens, statues played a significant role in thematic spectacles, such as fireworks and transparent paintings, which were intended to lure customers. Statues of political and military heroes, together with those of figures from Greek mythology, as well as copies of renowned statues, such as the Medici Apollo, also decorated commercial gardens.

Statues were especially important in sites of public commemoration, such as public squares. The fate of the gilded lead statue of George III in the Bowling Green in New York illustrates the political charge such monuments could carry. In 1776, after a public reading of the Declaration of Independence, the statue purportedly was pulled down by the assembled crowd and melted for bullets.[8] In 1800, Latrobe recorded that the statue of Lord Botetourt was damaged by students at the College of William and Mary, in Williamsburg, as a statement of protest against British aristocracy; it was subsequently moved to a private garden. Statues could instruct as well as incite. When planning the public space in the center of Washington, DC, Pierre-Charles L’Enfant included statues representing those who helped the United States achieve liberty and independence and individuals worthy of imitation and adulation. In the 19th century, statues became crucial elements in the new public parks. A. J. Downing, when describing in 1851 the benefits of a park in New York, pointedly stated that such a place would provide an appropriate setting for statues and other works of art that commemorated the history of the nation.

A choice of style or subject of the statue might have been justified in one garden because it harmonized with the architectural style of the home. On the other hand, it might have been praised for the pleasing contrast it offered from plants in the surrounding landscape. In American gardens, it is important to note that in spite of changing taste and fashion, statues as garden elements were always valued, and a place was found for them whether on the terrace or hidden in a grove.

—Anne L. Helmreich

Texts

Usage

- Stiles, Ezra, 1754, describing Bush Hill, estate of Lt. Gov. James Hamilton, near Philadelphia, PA (1892: 375)[9]

- “Took a walk in his very elegant garden, in which are 7 statues in fine Italian marble curiously wrot.” back up to History

- Fisher, Daniel, May 25, 1755, describing Bush Hill, estate of Lt. Gov. James Hamilton, near Philadelphia, PA (Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 17: 267)

- “it [did not] contain anything that was curious, unless what is by some gazed at and spoke of, a few very ordinary statues. A shady walk of high trees leading from the further end of the Garden, looked well enough; but the Grass above knee high, thin and spoiling for the want of the Sythe.” back up to History

- Sansom, Hannah Callender, June 30, 1762, diary entry describing Belmont, estate of William Peters, near Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Sansom 2010: 183)[10]

- “. . . a broad walk of english Cherre trys leads down to the river, the doors of the hous opening opposite admitt a prospect [of] the length of the garden thro' a broad gravel walk, to a large hansome summer house in a grean, from these Windows down a Wisto terminated by an Obelisk, on the right you enter a Labarynth of hedge and low ceder with spruce, in the middle stands a Statue of Apollo, note: in the garden are the Statues of Dianna, Fame & Mercury, with urns. we left the garden for a wood cut into Visto’s, in the midst a chinese temple, for a summer house, one avenue gives a fine prospect of the City, with a Spy glass you discern the houses distinct, Hospital, & another looks to the Oblisk.” back up to History

- Jefferson, Thomas, 1771, describing Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, VA (1944: 26)[11]

- “. . . the ground just about the spring smoothed and turfed; close to the spring a sleeping figure reclined on a plain marble slab, surrounded with turf; on the slab this inscription:

- Hujus nympha loci, sacri custodia fontis

- Dormio, dum blandae sentio murmur aquae

- Parce meum, quisquis tangis cava Marmora, summum

- Rumpere; si bibas, sive lavere, tace”

- Robert, Patrick M., August 1771, describing New York, NY (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “Near the fort is an equestrian statue of King George the III. Upon an elegant pedestial in the middle of a fine green rail’s in with iron. At the crossing of two public streets, stands at full length a marble statue of Lord Chatham erected by the citizens in gratitude for his strenuous opposition to the stamp act in 1766.”

- Fithian, Philip Vickers, April 7, 1774, describing Mount Airy, property of John Tayloe II, Richmond County, VA (1943: 126)[12]

- “He has also a large well formed, beautiful Garden, as fine in every Respect as any I have seen in Virginia. In it stand four large beautiful Marble Statues.” back up to History

- Washington, George, July 19, 1776, describing the toppling of the statue of George III in New York, NY (1931–44: 5:246)[14]

- “Tho the General doubts not the persons who pulled down and mutilated the statue, in the Broadway, last night, were actuated by Zeal in the public cause; yet it has so much the appearance of riot, and want of order, in the Army, that he disapproves of the manner, and directs that in future these things shall be avoided by the Soldiery, and left to be executed by proper authority.” [Fig. 9]

- L’Enfant, Pierre-Charles, January 4, 1792, describing Washington, DC (quoted in Caemmerer 1950: 165)[15]

- “The center of each Square will admit of Statues, Columns, Obelisks, or any other ornament such as the different States may choose to erect: to perpetuate not only the memory of such individuals whose counsels or Military achievements were conspicuous in giving liberty and independence to this Country; but also those whose usefulness hath rendered them worthy of general imitation, to invite the youth of succeeding generations to tread in the paths of those sages, or heroes whom their country has thought proper to celebrate.”

- Latrobe, Benjamin Henry, April 24, 1800, describing a statue in Williamsburg, VA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “A very striking proof of the folly of expecting that any statue will be always respected exists in Williamsburg, where Lord Botetourts statue which had remained untouched during the whole war, was mutilated, and decapitated, by the young collegians, in the first frenzy of the French revolutionary maxiums, because it was the statue of a Lord. The Statue now graces Mrs. Hunt’s Garden in a very mutilated state. The pedestal has these inscriptions which remained the libel of the country and age, beneath the decapitated statue in 1797. . . I could furnish you with many other proofs of the perishability of statues, and the immortality of pyramids, from Rome Westminster Abbey, the cedevant place Louis XV, the cidevant Church St. Genevieve, Egypt, Greece and Italy, and (if Mr. Reed will permit) from South Carolina. General Washington’s statue at Richmond has already lost a spur. We know that even his virtues are hated, by fools and rogues, and unfortunately that sort of animals crawl much about in public buildings.”

- Anonymous, June 24, 1805, describing Vauxhall Garden, New York, NY (New York Daily Advertiser)

- “[Joseph Delacroix has] procured from Europe a choice selection of Statues and Busts. mostly from the finest models of Antiquity, and worthy the attention of Amateurs. . .

- “The BUSTS and STATUES. . .

“Gen. Washington, Gen. Hamilton, Addison “Cicero, Demosthenes Antinous “Ajax, Apollo B. Cleopatra “Antinious, Plenty Niobe “Hannibal, Hercules Pompey “Apollo di Belvedere Time Pope “[different sizes] Ceres “Venus, Serenity “Hebe, Modesty “Apollo di Medicis—THALIA, Comic Muse.”

- Anonymous, December 7, 1805, describing a botanic garden in Charleston, SC (Charleston Courier)

- “BOTANIC GARDEN. One Hundred Dollars Reward. On Thursday Evening last, after sun-set, some evil minded person, taking advantage of the Gardener’s absence, knocked the Gate, and on being admitted treated the servant insolently for not admitting him sooner; he went directly to the Statue of Mercury, which was standing in the middle of the Garden, and threw it down, by which means it is entirely destroyed. The man was well dressed.”

- Drayton, Charles, November 2, 1806, describing The Woodlands, seat of William Hamilton, near Philadelphia, PA (Drayton Hall, Charles Drayton Diaries, 1784–1820, typescript)

- “The Garden consists of a large verdant lawn surrounded by a belt or walk, & shrubbery for some distance. the outer side of the walk is adorned here & there, by scattered forest trees, thick & thin. It is bounded, partly as is described—partly by the Schylkill [sic] & a creek exhibiting a Mill & where it is scarcely noticed, by a common post and rail. The walk is said to be a mile long—perhaps it is something less. one is led in to the garden from the portico, to the east and lefthand. or from the park, by a small gate contiguous to the house. traversing this walk, one sees many beauties of landscape—also a fine statue, symbol of Winter, & age.” [Fig. 10] back up to History

- Smith, John Rubens, c. 1810, describing the home of Timothy Dexter, Newburyport, MA

- “A View of the Mansion of the late LORD TIMOTHY DEXTER in High Street, Newbury port. 1801. The Statues or rather Images have no pretentions to correctness of Character or even proportion but are faithfully delineated in order to convey a just representation of one of the Whims of this most truly excentric Character whose many singularities of Conduct and Speculations by which he acquired from the smallest beginnings a splendid Fortune are to be found in the Account of his Life . . .” [Fig. 11]

- Lambert, John, 1816, describing Vauxhall Garden, New York, NY (1816: 2:61)[16]

- “The Vauxhall garden is situated in the Bowery Road about two miles from the City Hall. It is a neat plantation, with gravel walks adorned with shrubs, trees, busts, and statues. In the centre is a large equestrian statue of General Washington.”

- Rush, William, July 20, 1820, describing his choice of wood for statues (quoted in Thompson 1982: 29–30)[17]

- “We pretend not to say that wooden statues are as elegant as marble. The contour may be as graceful, but there is a fineness in the lines of a marble figure which give it a great superiority. Wooden statues are, however, well adapted to the present state of this country, and seem perfectly appropriate in a Sylvan state. They cost only one-twelfth as much as marble statues: and will last quite as long as the buildings they are intended to ornament.” [Fig. 12]

- Peale, Charles Willson, c. 1825, describing the Brideswell (Workhouse), New York, NY (Miller et al., eds., 2000: 5:167–68)[18]

- “In the garden they saw the remains of the statue of Mr. Pitt. . . the head was gone and other parts much mutilated, This was done by the British, pehaps because the americans had broken to pieces the statue of King George, which was an equistrian statue of Lead, which they cast into bullets.”

- Peale, Charles Willson, c. 1825, describing Belfield, estate of Charles Willson Peale, Germantown, PA (Miller et al., eds., 2000: 5:381–82)[18]

- “He wanted a place to keep the garden seeds & Tools, and in a part of the Garden where a seat in the shade was often wanted, he built a shed or small room, and to hide that Salt-like-box, and to try his art of Painting, he made the front like [a] Gate Way with a step to form a seat, and above, steps painted as representing a passage through an Arch beyond which was represented a western sky, and to ornament the upper part over the arch, he painted several figures on boards cut to the outlines of said figures as representing statues in sculpture. And [so that] his design of those figures might be fully understood [by] visitors, he painted two pedestals ornamented with a ball to crown each. and the die of the Pedestals, on one the expla[na]tion of the figures vizt. America with an even ballance—as justifying her acts. The Fassie, emblematical of the several state[s], are bound together, incircled by a Rattle-snake, as inocent if not meddled with, but terrible if molested. This emblem of Congress is placed upright as that body ought to be, with wisdom its base, designed by the owl; the beehive and children; industry an increase the effects of good government, supported on one side, Truth and Temperance, on the other Industry, with her distaf, resting on the cornucopia— consequence a wise Policy will do away with wars. hence Mars is fallen. The figure of Mars was made on the end of shed roof to hide it. The making of this is rather of the Political cast, yet he had long given over being active in Politicks, but choose by it to shew his dislike of War.” back up to History

- Trollope, Frances Milton, 1830, describing Fairmount Waterworks, Philadelphia, PA (1832: 2:44)[19]

- “At another point, a portion of the water in its upward way to the reservoir, is permitted to spring forth in a perpetual jet d’eau, that returns in a silver shower upon the head of a marble naïad of snowy whiteness. The statue [Rush’s Allegory of the Schuylkill River] is not the work of Phidias, but its dark, rocky back-ground, the flowery catalpas which shadow it, and the bright shower through which it shews itself, altogether makes the scene one of singular beauty.” [Fig. 13]

- Lyell, Sir Charles, 1846, describing Natchez, MS (1849: 2:153)[20]

- “Many of the country-houses in the neighborhood are elegant, and some of the gardens belonging to them laid out in the English, others in the French style. In the latter are seen terraces, with statues and cut evergreens, straight walks with borders of flowers, terminated by views into the wild forest, the charms of both being heightened by contrast. Some of the hedges are made of that beautiful North American plant, the Gardenia, miscalled in England the Cape jessamine, others of the Cherokee rose, with its bright and shining leaves.”

- Walter, Cornelia W., 1847, describing Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, MA (1847: 105, 110–11)[21]

- “Erected upon a granite foundation, and facing the main entrance to Mount Auburn, stands the imposing bronze statue of the venerable Dr. Bowditch. . .

- “The monument which has been recently placed in Mount Auburn, is the first bronze statue of any magnitude in our country. . .

- “The statue has been erected by subscription, and placed in a conspicuous position amidst the woody foliage of Mount Auburn.” [Fig. 14]

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1849, describing Lemon Hill, estate of Henry Pratt, Philadelphia, PA (1849; repr., 1991: 43)[22]

- “Lemon Hill, half a mile above the Fairmount water-works of Philadelphia, was, 20 years ago, the most perfect specimen of the geometric mode in America, and since its destruction by the extension of the city, a few years since, there is nothing comparable with it, in that style, among us. All the symmetry, uniformity, and high art of the old school, were displayed here in artificial plantations, formal gardens with trellises, grottoes, spring-houses, temples, statues, and vases, with numerous ponds of water, jets-d’eau, and other water-works, parterres and an extensive range of hothouses.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, August 1851, “The New-York Park” (Horticulturist 6: 347)[23]

- “The many beauties and utilities which would gradually grow out of a great park like this, in a great city like New-York, suggest themselves immediately and forcibly. Where would be found so fitting a position for noble works of art, the statues, monuments, and buildings commemorative at once of the great men of the nation, of the history of the age and country, and the genius of our highest artists?”

Citations

- Dezallier d’Argenville, Antoine-Joseph, 1712, The Theory and Practice of Gardening (1712: 75–76)[24]

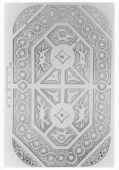

- “STATUES and Vases contribute very much to the Embellishment and Magnificence of a Garden, and extremely advance the natural Beauties of it. . .

- “THESE Figures represent all the several Deities, and illustrious Persons of Antiquity, which should be placed properly in Gardens, setting the River-Gods, as the Naiades, Rivers, and Tritons, in the Middle of Fountains and Basons; and those of the Woods, as Sylvanes, Faunes, and Dryads, in the Groves.” [Fig. 15]

- Langley, Batty, 1728, New Principles of Gardening (1728; repr., 1982: 195–206)[25]

- “General DIRECTIONS, &c. . . .

- “XIX. That in those serpentine Meanders, be placed at proper Distances, large Openings, which you surprizingly come to; and in the first are entertain’d with a pretty Fruit-Garden, or Paradice-Stocks, with a curious Fountain; from which you are insensibly led through the pleasant Meanders of a shady delightful Plantation; first, into an oven [sic] Plain environ’d with lofty Pines, in whose Center is a pleasant Fountain, adorn’d with Neptune and his Tritons, &c. secondly, into a Flower-Garden, enrich’d with the most fragrant Flowers and beautiful Statues; and from thence through small Inclosures of Corn, open Plains, of small Meadows, Hop-Gardens, Orangeries, Melon-Grounds, Vineyards, Orchards, Nurseries, Physick Gardens, Warrens, Paddocks of Deer, Sheep, Cows, &c. with the rural Enrichments of Hay-Stacks, Wood-Piles, &c. . . .

- “XXXVII. There is nothing adds so much to the Beauty and Grandeur of Gardens, as fine Statues; and nothing more disagreeable, than when wrongly plac’d; as Neptune on a Terrace-Walk, Mount, &c. or Pan, the God of Sheep, in a large Basin, Canal, or Fountain. But to prevent such Absurdities, take the following Directions.

- “For open Lawns and large Centers:

- “Mars, God of Battle, with the Goddess Fame; Jupiter, God of Thunder, with Venus, the Goddess of Love and Beauty; and the Graces Aglaio, Thalia, and Euphrosyne; Apollo, God of Wisdom, with the nine Muses, Cleio, Melpomene, Thalia, Euterpe, Terpsicoce, Erato, Calliope Urania, and Polymina; Minerva and Pallas, Goddesses of Wisdom, with the seven Liberal Sciences; the three Destinies, Clotho, Lachesis, and Atropos; Demegorgon and Tellus, Gods of the Earth; Priapus, the Garden-God; Bellona, Goddess of War; Pytho, Goddess of Eloquence; Vesta, Goddess of Chastity; Voluptia, Goddess of Pleasure; Atlas, King of Mauritania, a famous Astronomer; Tysias, the Inventor of Rhetorick; and Hercules, God of Labour.

- “Ceres and Flora; Sylvanus, God, and Ferona, Goddess of the Woods; Actaeon, a Hunter, whom Diana turn’d into a Hart, and was devoured by his own Dogs; Eccho, a Virgin rejected of her Lover, pined away in the Woods for Sorrow, where her Voice still remains, answering the Outcries of every Compaint, &c. Philomela, a young Maid ravish’d by Tereus, who afterwards imprison’d her, and cut out her Tongue; which cruel Action Progne, Sister to Philomela and Wife to Tereus, reveng’d, by killing her own son Itis, whom she had by Tereus, and mincing his Flesh, dress’d up a Dish thereof, which she gave her Husband Tereus to eat, (unknown to him,) instead of Meat. Philomela was afterwards transformed into a Nightingale, and Itis into a Pheasant; and lastly, Nuppaeae Fairies of the Woods.

- “Neptune, Palemon, Paniscus, and Oceanus, Gods, and Dione, Melicerta, Thetis, and Marica, Goddesses of the Sea; Salacia Goddess of Water; Naiades Fairies of the Water; and the Syrens Parthenope, Lygia, and Leusia.

- “Niches to be adorn’d with Dii minores.

- “For Fruit-Gardens and Orchards:

- “Pomona Goddess of Fruit, and the three Hesperides, Eagle, Aretusa, and Hisperetusa, who were three Sisters that had an Orchard of golden Apples kept by a Dragon, which Hercules slew when he took them away.

- “For Flower-Gardens:

- “Flora and Cloris, Goddesses of Flowers; and also Venus, Diana, Daphne, and Runcina the Goddess of Weeding.

- “For the Vineyard:

- “Bacchus God of Wine.

- “Aeolus, God of the Winds and Orcedes Fairies of the Mountains.

- “For Valleys:

- “The Goddess Vallonta.

- “For private Cabinets in a Wilderness or Grove:

- “Harpocrates God, and Agernoa Goddess of Silence, Mercury God of Eloquence.

- “For small Paddocks of Sheep, &c. in a Wilderness:

- “Morpheus and Pan Gods of Sheep; Pates the Shepherds Goddess; Bubona the Goddess of Oxen; and Nillo a famous Glutton, who used himself to carry a Calf every Morning, until it became a large Bull, at which Time he slew it with his Fist, and eat him all in one Day.

- “For small Enclosures of Wheat, Barley, &c. in a Wilderness:

- “Robigus a God who preserved Corn from being blasted; Segesta a Goddess of the Corn, and Tutelina a Goddess, who had the Tuition of Corn in the Fields.

- “For Ambuscadoes near Rivers, Paddocks, or Meadows:

- “For those near a Canal or River, Ulysses, who first invented the Shooting of Birds; and for those near a Paddock, wherein Sheep, &c. are kept, Cacus slaying by Hercules. For Cacus being a Shepherd, and a notorious Theif [sic] of great Strength and Policy, stole several Sheep and Oxen from Hercules, who perceiving his Loss, lay in Ambush, and took Cacus in the Fact, for which, with his Club, he knock’d out his Brains.

- “Lastly, for Places of Banquetting:

- “The God Comus.

- “Where Bees are kept in Hives:

- “The God Aristeus.” [Fig. 16] back up to History

- Ware, Isaac, 1756, Complete Body of Architecture (1756: 34–35, 650)[26]

- “STATUE.

- “The representation of some person distinguished by his actions, and placed free from any wall, and as an ornament for buildings. Statues are, according to their bigness, divided into four kinds; those smaller than life, those as big as life, those somewhat bigger, and lastly, those twice, or ever so much more than twice as big. These are called colossi, or colossal statues. . .

- “TERMINUS.

- “A kind of column adorned at the top with the head and sometimes part of the body of a man, woman, or pagan diety; and in the lower part diminishing into a kind of sheath or scabbard, as if the remainder of the figure were received into it. The common use of the termini is by way of statues to adorn gardens, but they are sometimes also placed as consoles or brackets to support entablatures. . .

- “Thus may the groves be constructed ornamentally to the other parts of the garden, elegant and pleasing in themselves, and fit to form recesses in which to place statues, temples, and other structures.” back up to History

- Whately, Thomas, 1770, Observations on Modern Gardening (1770; repr., 1982: 138)[27]

- “vases, statues, and termini, are usual appendages to a considerable edifice; as such they may attend the mansion, and trespass a little upon the garden, provided they are not carried so far into it as to lose their connection with the structure.”

- Marshall, Charles, 1799, An Introduction to the Knowledge and Practice of Gardening (1799: 1:123)[28]

- “Gardens, were formerly loaded with statues, and great improprieties were committed in placing them, as Neptune in a grove, and Vulcan at a fountain, large figures in small gardens, and small in large, &c. but, perhaps, works of statuary might still be introduced, and the meeting with Flora, Ceres, or Pomona, &c. well executed, and in proper places, could hardly give offence.”

- M’Mahon, Bernard, 1806, The American Gardener’s Calendar (1806: 58, 64)[29]

- “In various parts of the pleasure-ground, leave recesses and other places surrounded with clumps of trees and shrubs, for the erection of garden edifices, such as temples, grottos, rural seats, statues, &c. . . .

- “In some spacious pleasure-grounds various light ornamental buildings and erections are introduced, as ornaments to particular departments; such as temples, bowers, banquetting houses, alcoves, grottos, rural seats, cottages, fountains, obelisks, statues, and other edifices; these and the like are usually erected in the different parts, in openings between the divisions of the ground, and contiguous to the terminations of grand walks, &c. . . .

- “Fountains and statues, are generally introduced in the middle of spacious opens; statues are also often placed at the terminations of particular walks, sometimes in woods, thickets, and recesses, upon mounts, terraces, and other stations, according to what they are intended to represent.”

- Gregory, G. (George), 1816, A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (1816: 2:n.p.)[30]

- “Gardens were formerly loaded with statues, and great improprieties were committed in placing them, as Neptune in a grove, and Vulcan at a fountain, large figures in small gardens, and small in large, &c. but perhaps the works of the statuary might still be introduced if well executed, and in proper places. . . .”

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826: 361, 810)[31]

- “1843. Sculptures. Of statues, therms, busts, pedestals, altars, urns, and similar sculptures, nearly the same remark may be made. Used sparingly, they excite interest, often produce character, and are always individually beautiful, as in the pleasure-grounds of Blenheim, where a few are judiciously introduced; but profusely scattered about, they distract attention. . .

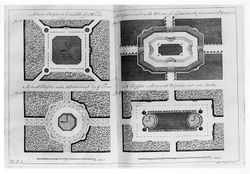

- “6158. Statues, whether of classical or geographical interest (figs. 564. and 565.), urns, inscriptions, busts, monuments, &c. are materials which should be introduced with caution. None of the others require so much taste and judgement to manage them with propriety. The introduction of statues, except among works of the most artificial kind, such as fine architecture, is seldom or never allowable; for when they obtrude themselves among natural beauties, they always disturb the train of ideas which ought to be excited in the mind, and generally counteract the character of the scenery. In the same way, busts, urns, monuments, &c. in flower-gardens, are most generally misplaced. The obvious intention of these appendages is to recall to mind the virtues, qualities, or actions of those for whom they were erected: now this requires time, seclusion, and undisturbed attention, which must either render all the flowers and other decoration of the ornamental garden of no effect; or, if they have effect, it can only be to interrupt the train of ideas excited by the other. As the garden, and the productions of nature, are what are intended to interest the spectator, it is plain that the others should not be introduced.” [Figs. 17 and 18]

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828: 2:n.p.)[32]

- “STAT’UE, n. [L. statua; statuo, to set; that which is set or fixed.]

- “An image; a solid substance formed by carving into the likeness of a whole living being; as a statue of Hercules or of a lion.” back up to History

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, August 1836, “Remarks on the Fitness of the different Styles of Architecture for the Construction of Country Residences, and on the Employment of Vases in Garden Scenery” (American Gardeners’ Magazine 2: 283–85)[33]

- “There can scarcely be a more appropriate, agreeable and beautiful residence for a citizen who retires to the country for the summer, than a modern Italian villa, with its ornamented chimneys, its broad verandah, forming a fine shady promenade, and its cool breezy apartments. Placed where a pleasant prospect could be enjoyed—a few statues distributed with taste over the well-kept lawn—a few Italian poplars, with their conical summits rising out of the gracefully-rounded clumps of foliage which should surround it—the whole would be quite perfect and delightful. . .

- “It will not be inadvertent to the present hasty remarks to hint at the additional charm which may be produced in highly finished places, especially where the buildings are in the Grecian style, by introducing into the lawns and gardens the classic vase in its different forms,*and, if thought desirable, statues also. They serve as it were as a connecting link between so highly artificial an object as a modern villa, and the verdant lawns and gay gardens which surround it. Elevated upon pedestals, and placed at suitable points in the view—on the parapets of terraces near the house—before a group of foliage upon the lawn, and at proper intervals in the garden, they give a classic and elegant air to the whole, which adds greatly to its value. Beautiful in their forms, contrasting finely with the deep green of vegetation, and leading the eye gradually from their own sculptured beauty to the architectural symmetry of the building, of which they form as it were a continuous though detached part, amalgamating it with the grounds in which it is placed—their effect can only be appreciated beforehand by those who have studied the excellent effect produced by their introduction into the scene.”

- Anonymous, April 1847, "Hints on Flower Gardens" (Horticulturalist 1: 444) [34]

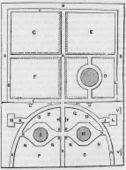

- ". . . still another most delightful scene is reserved, a so-called Rococo garden. . . A garden, laid out in this manner, demands much cleverness and skill in the gardener. . . Around it the most charming landscape open to the view, gently swelling hills, interspersed with pretty village, gardens and grounds. In the plan of the garden, a and b are massed of shrubs; c, circular beds, separated by a border or belt of turf, e, from the serpentine bed, d. The whole of this running pattern is surrounded by a border of turf, f; g and h are gravel walks; i, beds, with pedestal and statue in the centre; k, small oval beds, separated from the bed, l, by a border or turf; m, n, o, p, irregular arabesque bed, set in turf."

- Downing, A. J., 1849, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849; repr., 1991: 21, 30, 62–63, 92, 531)[22]

- “The beauties elicited by the ancient style of gardening were those of regularity, symmetry, and the display of labored art. These were attained in a merely mechanical manner. . . The geometrical form and lines of the buildings were only extended and carried out in the garden. In the best classical models, the art of the sculptor conferred dignity and elegance on the garden, by the fine forms of marble vases and statues.” [Fig. 19]

Images

Inscribed

John Rubens Smith (engraver), “A View of the Mansion of the late LORD TIMOTHY DEXTER in High Street, Newbury port. 1810,” 1810—20. “The Statues or rather Images. . .”

J. C. Loudon, Statue of classical interest, in An Encyclopædia of Gardening, 4th ed. (1826), 810, fig. 564. “Statues, whether of classical or geographical interest (figs. 564. and 565.). . .”

J. C. Loudon, Statue of geographical interest, in An Encyclopædia of Gardening, 4th ed. (1826), 810, fig. 565. “Statues, whether of classical or geographical interest (figs. 564. and 565.). . .”

Anonymous, "The Rococo Garden of Baron Hügel, near Vienna," Horticulturist, vol. 1, no. 10 (April 1847), pl. opp. p. 441. "i, beds, with pedestal and statue in the centre."

Associated

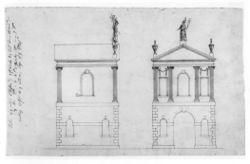

Samuel McIntire, Elevation of the summer house designed for the Elias Hasket Derby Farm, n.d.

William Strickland, “The Woodlands,” 1809, in Casket 5, no. 10 (October 1830): pl. opp. 432.

Joseph Drayton, View near Bordenton, from the gardens of the Count de Survilliers, c. 1820.

James Smillie, “The Bowditch Monument, Mount Auburn Cemetery,” in Cornelia W. Walter, Mount Auburn Illustrated (1847; repr., 1850), opp. 105.

Anonymous, “The Geometric style, from an old print,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), 62, fig. 14.

Attributed

Wilfred A. French (photographer), Exterior view of the Summer House, Royall House, Medford, MA, n.d.

Charles Willson Peale, John Beale Bordley, 1770.

Charles Willson Peale, Charles Carroll, c. 1770.

Anne-Marguerite-Henriette Rouillé de Marigny Hyde de Neuville, The Moreau House, July 2, 1809.

John Lewis Krimmel, Fourth of July in Centre Square, 1812.

George Bridport, Alternative designs for Washington Monument, Washington Square, Philadelphia, 1816.

Thomas Charles Millington, View of the Campus of The College of William and Mary, 1840.

Augustus Köllner, “President’s House,” 1848. The statue is located on the lawn in front of the White House.

Anonymous, “Residence of Gov. Morehead, North Carolina,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), 387, fig. 46.

Edward Weber, View of Washington City and Georgetown [detail], 1849.

Augustus Weidenbach, Belvedere, c. 1858.

Charles Willson Peale, Mary White (Mrs. Robert) Morris (1749-1827), from life, c. 1782.

Notes

- ↑ Wayne Craven, Sculpture in America (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1984), 15, view on Zotero.

- ↑ A.-J. Dézallier d’Argenville, The Theory and Practice of Gardening, trans. John James (1712; repr., Farnborough, England: Gregg International, 1969), 75–76, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson, The Garden Book, ed. Edwin M. Betts (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1944), 26, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Craven 1984, 14–15, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel L. Knapp, Life of Lord Timothy Dexter (Newburyport, MA: John G. Tilton, 1848), 19–20. According to Craven, “The only known surviving pieces [of Dexter’s assemblage] are two arms of a figure, now in the Newburyport Historical Society, and the figure of William Pitt, restored and preserved in the Smithsonian Institution in Washington. The figure is rather stiff and clearly belongs to the tradition of the figurehead carver” (see Craven 1984, 20), view on Zotero.

- ↑ D. Dodge Thompson, “The Public Work of William Rush: A Case Study in the Origins of American Sculpture,” in William Rush, American Sculptor, exh. cat. (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 1982), 29–30, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Hebron Moore, “A View of Philadelphia in 1829: Selections from the Journal of B.L.C. Wailes of Natchez,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 78 (July 1954): 353–60. Alexander Pope’s garden at Twickenham had a similar statue of a dog guarding the grotto, view on Zotero.

- ↑ See Craven 1984, 47–50, for a description of this statue, as well as one depicting William Pitt, both made by the British sculptor Joseph Wilton (1722–1803). These were two of four monumental statues in colonial America, the other being a copy of the William Pitt for Charleston, South Carolina, and Richard Hayward’s marble statue of Lord Botetourt in Williamsburg, Virginia. The political associations of statues could also be used in private contexts. In Charles Willson Peale’s portrait (1770) of John Beale Bordley I, the sitter is shown pointing at a statue of English law around the base of which grows poisonous jimson weed, symbolizing Bordley’s claim that the British Parliament was bent on destroying itsown laws of liberty in the Americas. It is not known if Bordley had such a statue at his Wye River estate, view on Zotero.

- ↑ “Ezra Stiles in Philadelphia, 1754,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 16 (1892): 375–76, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Hannah Callender Sansom, The Diary of Hannah Callender Sansom: Sense and Sensibility in the Age of the American Revolution, eds. Susan E. Klepp and Karin Wulf (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2010), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson, The Garden Book, ed. Edwin M. Betts (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1944), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Philip Vickers Fithian, Journal & Letters of Philip Vickers Fithian, 1773–1774: A Plantation Tutor of the Old Dominion, ed. Hunter D. Farish (Williamsburg, VA: Colonial Williamsburg, 1943), view on Zotero.

- ↑ The pictorial resurgence of the fall of George III is treated by Wendy Bellion in her volume "Iconoclasm in New York: Revolution to Reenactment," (Pennsylvania University Press, 2019), view on Zotero.

- ↑ George Washington, The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources, 1745–1799, ed. John C. Fitzpatrick, 39 vols. (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1931), view on Zotero.

- ↑ H. Paul Caemmerer, The Life of Pierre-Charles L’Enfant, Planner of the City Beautiful, The City of Washington (Washington, DC: National Republic Publishing Company, 1950), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Lambert, Travels through Canada, and the United States of North America in the Years 1806, 1807, and 1808, 2 vols. (London: Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy, 1816), view on Zotero.

- ↑ D. Dodge Thompson, “The Public Work of William Rush: A Case Study in the Origins of American Sculpture,” in William Rush, American Sculptor (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, 1982), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Lillian B. Miller et al., eds., The Selected Papers of Charles Willson Peale and His Family, vol. 5, The Autobiography of Charles Willson Peale (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Frances Trollope, Domestic Manners of the Americans, 3rd ed., 2 vols. (London: Wittaker, Treacher, 1832), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Sir Charles Lyell, A Second Visit to the United States of North America, 2 vols. (New York: Harper, 1849), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Cornelia Walter, Mount Auburn Illustrated in a Series of Views from Drawings by James Smillie (New York: Martin and Johnson, 1847) view on Zotero.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening. . . , 4th ed. (1849; repr., Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. Downing, “The New-York Park,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 6, no. 8 (August 1851): 345–49, view on Zotero.

- ↑ A.-J. (Antoine Joseph) Dézallier d’Argenville, The Theory and Practice of Gardening; Wherein Is Fully Handled All That Relates to Fine Gardens, . . . Containing Divers Plans, and General Dispositions of Gardens. . . , trans. John James (London: Geo. James, 1712), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Batty Langley, New Principles of Gardening, or The Laying out and Planting Parterres, Groves, Wildernesses, Labyrinths, Avenues, Parks, &c. (London: A. Bettesworth and J. Batley, etc., 1728; repr. New York: Garland, 1982), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Isaac Ware, A Complete Body of Architecture (London: T. Osborne and J. Shipton, 1756),view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Whately, Observations on Modern Gardening, 3rd ed. (1770; repr., London: Garland, 1982),view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Marshall, An Introduction to the Knowledge and Practice of Gardening, 1st American ed., 2 vols. (Boston: Samuel Etheridge, 1799), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bernard M’Mahon, The American Gardener’s Calendar: Adapted to the Climates and Seasons of the United States. Containing a Complete Account of All the Work Necessary to Be Done. . . for Every Month of the Year. . . (Philadelphia: Printed by B. Graves for the author, 1806), view on Zotero.

- ↑ George Gregory, A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences, 1st American ed., 3 vols. (Philadelphia: Isaac Peirce, 1816), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, 4th ed. (London: Longman et al., 1826), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. Downing, “Remarks on the Fitness of the different Styles of Architecture for the Construction of Country Residences, and on the Employment of Vases in Garden Scenery,” American Gardeners’ Magazine, and Register of Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Horticulture and Rural Affairs 2, no. 8 (August 1836): 281–86, view on Zotero.

- ↑ The Horticulturist and journal of rural art and rural taste 1., no. 10, (April 1847): 441-445, view on Zotero.