Green

See also: Bowling green, Common, Lawn, Plot, Square

History

The term green in American landscape design was used to describe two types of landscape features. The first was level plats or lawns, often the setting for garden buildings such as the summerhouse described in 1762 at Belmont, Judge William Peters's estate near Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, or other garden features, such as the basin at Crowfield, William Middleton’s plantation near Charleston, South Carolina, reported by Eliza Lucas Pinckney in 1743. These lawns sometimes had utilitarian functions, as with the “bleaching green” that Walter Elder described in 1849 for whitening laundry in the sunshine (view text). The usage of the term to describe a level lawn may have been related to “greensward” (used rarely but synonymously with lawn) or bowling green, although these connections are not articulated in any of the treatises or descriptions (see Bowling green and Lawn).

The second and more frequent use of the term referred to open public spaces, generally centrally located in towns or villages and particularly characteristic of New England settlements, such as that described by John Warner Barber (1844) at Taunton, Massachusetts (view text). For a detailed discussion of the variety of New England settlement patterns, and the history of open spaces in town planning, see Common. Like commons and squares, greens were admired for their spaciousness within the close confines of a town, as conveyed by the descriptions of Newcastle, Delaware, in 1727 and New Haven, Connecticut, in 1750. Town greens also provided open space for communal gatherings such as military exercises, markets, or special ceremonial occasions such as the Cherokee dance performance on the green of the Governor’s Palace in Williamsburg, Virginia [Fig. 1], or the Marquis de Lafayette’s procession in Newark, New Jersey, in 1824. Greens set the stage for the kind of social promenading and recreation depicted in William Russell Birch's illustration of the State House Yard in Philadelphia [Fig. 2]. In addition to serving multiple purposes as a communal space, the green was often a setting for prominent public buildings: meetinghouses, watch houses, and government buildings. Greens were also used for the purpose of burying grounds, as at New Haven, and Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. These public greens were landscaped with grass, walkways or paths, and shade trees, often planted around the perimeter or alongside the walks. The level of ornamentation ranged from the simple tree plantings, as depicted in Barber’s view of Newark [Fig. 3], to more elaborate plantings, such as the rows of elms and poplars and gravel walks described by William Dickinson Martin in 1809 in Philadelphia (view text). Chronologically, these designs register an increasing use of ornamentation, particularly in New England in the second quarter of the 19th century, reflecting the prosperity and development of the village commercial centers.

New Haven Green, one of the best-known and documented examples of this feature in the United States, provides an interesting case study of communal space in the history of American landscape design.[1] The nine-square plan was laid out in 1638 by London merchant Theophilus Eaton.[2] As the 1748 plan [Fig. 4] indicates, the outer squares were divided into lots. The central square, however, was kept intact and used for a variety of purposes and public buildings at different points in time. In 1639, it was the scene of a public display of the decapitated head of a Native American accused of murdering English settlers,[3] and in 1645 it was the gathering place for the Artillery Company. Between 1638 and 1665 it was the location of the watch house, the prison house, and a schoolhouse. A meetinghouse was authorized on the site in 1639, one of a series whose successor may be seen on the 1748 map. The various civic uses of the central space are reflected in its numerous early appellations. The first reference to the space as a “markett place” occurred in 1639, but it was not until 1759 that the term “green” first appeared in print in an advertisement in the Connecticut Gazette. These two designations were used interchangeably until 1784 when the officials of the newly incorporated city began to use the more cosmopolitan sounding “Public Square” and “Great Square.” According to recent scholarship, the term “green” continued to be used popularly in New Haven, but it was not until after the Civil War that the “New Haven Green” became the clear title of the city’s central space.

—Elizabeth Kryder-Reid

Texts

Usage

- Ross, George, March 1, 1727, describing Newcastle, DE (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “In the middle of the Town lies a spacious green in form of a square, in a corner whereof stood formerly a Fort &c.”

- Pinckney, Eliza Lucas, May 1743, describing Crowfield, plantation of William Middleton, vicinity of Charleston, SC (1972: 61)[4]

- “. . . as you draw nearer [the house] new beauties discover themselves. . . a spacious bason in the midst of a large green presents itself as you enter the gate that leads to the house.”

- Birket, James, October 9, 1750, describing Yale College, New Haven, CT (1916: 36)[5]

- “YALE COLLEDGE [sic]. . . A new one [structure] of Brick which Seems to be About 3 foot Above the Ground & And will front towards a large Spacious green in the Middle of the town.” [Fig. 5]

- Sansom, Hannah Callender, June 30, 1762, diary entry describing Belmont, estate of William Peters, near Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Callender 2010: 183)[6]

- “. . . a broad walk of english Cherre trys leads down to the river, the doors of the hous opening opposite admitt a prospect [of] the length of the garden thro’ a broad gravel walk, to a large hansome summer house in a grean. . .”

- Anonymous, June 12, 1777, describing the peace talks with Cherokee nation in Williamsburg, VA (Maryland Gazette)

- “After the talk was concluded, they [the members of the Cherokee nation] favoured the public with a dance on the green in front of the palace, where a considerable number of spectators, both male and female, were agreeably entertained.”

- Strickland, William, November 2, 1794, describing Weathersfield, MA (1971: 198)[7]

- “This is one of the neatest towns I have seen since I enterd the New-England States where all the towns are neat: it consists of many good houses detached from each other, or scatterd along a wide street, or rather along the edge of a Green of excellent turf, on a sandy soil keeping itself continually dry and firm.”

- Dwight, Timothy, 1796, describing New Haven Green, New Haven, CT (1821: 1:190–91)[8]

- “Indubitable proofs of the enterprise of the inhabitants are seen in the Institutions already mentioned. . . Of these, levelling and enclosing the green, accomplished by subscription, at an expense of more than two thousand dollars, and the establishment of a new public cemetery, accomplished at a much greater expense, are particularly creditable to their spirit.”

- Strickland, William, September 24, 1796, describing Newark, NJ (1971: 67)[7]

- “This town strikingly resembles many of the neat villages in the southern counties of England, consisting of a mixture of stone, brick, and weatherboarded houses, many of them handsome and eligant, and all bearing the appearance of comfort and neatness, scatterd on the edge of an open green, spotted here and there with a large Hickory, or Black-wallnut-tree, with a little garden in front of each; It is not easy to meet with a more pleasing scene.”

- Martin, William Dickinson, May 20, 1809, describing the State House Yard, Philadelphia, PA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation),

- “The State House. . . is a large building on the south side of Chestnut Street. . . Attached to the State House, is a large green occupying a whole square to Walnut Street. [See Fig. 2] This is a neat place, ornamented with rows of Elms & Poplars: as also having handsome gravel walks, one of which extends thro' the Centre with grass plots on each side. The whole is enclosed in high brick walls.” back up to History

- Martin, William Dickinson, May 21, 1809, describing Princeton, NJ (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “In front of it [the College] is a very handsome green square of about four Acres, enclosed in a railing, & produces very fine herbage. It is attached to the College as a place of recreation & amusement for the students.” [Fig. 6]

- Silliman, Benjamin, 1824, describing Sandy Hill, NY (1824: 136–39)[9]

- “This pretty and flourishing village is regularly laid out, and composed of neat and handsome houses, many of which surround a beautiful central green. . .

- “Sandy Hill. . . is an incorporated village, exhibiting a great appearance of neatness and comfort. It is said to be very healthy. I observed the citizens busied in sweeping their public green with brooms, and in cleaning their streets—a commendable example for other villages; it is done here by a kind of common law.”

- Forman, Martha Ogle, September 1, 1824, describing the entrance of the Marquis de Lafayette into Newark, NJ (1976: 187)[10]

- “The entrance of La Fayette into Newark was very interesting, he was ushered in by the firing of Cannon and ringing of bells. They had erected on the green a number of arches representing the different states, all wreathed with Laurels and the effect was very beautiful.”

- Douglass, Frederick, 1825, describing Wye House, estate of Col. Edward Lloyd, Talbot County, MD (1855; repr., 1987: 46)[11]

- “There was a windmill (always a commanding object to a child’s eye) on Long Point—a tract of land dividing Miles river from the Wye—a mile or more from my old master’s house. There was a creek to swim in, at the bottom of an open flat space, of twenty acres or more, called 'the Long Green'—a very beautiful play-ground for the children.”

- Adams, Nehemiah, 1838, describing Fort Hill, Boston, MA (1838: 24)[12]

- “After the Common, we ought to mention the green upon Fort Hill, which serves the appropriate purpose of a play-ground for one of our public schools—such an one as every school ought to have access to.”

- Willis, Nathaniel Parker, 1840, describing New Haven Green, New Haven, CT (1840; repr., 1971: 219)[13]

- “In the centre of New Haven were originally laid out two open squares, divided by a street kept sacred from private buildings. The upper green is a beautiful slope, edged with the long line of the college edifices. Between the two squares stand three churches, at equal distances; two of the common order of architecture for places of public worship in this country (immense brick buildings, with tall white spires); and a third, which is presented in the drawing, a Gothic episcopal church, of singular purity and beauty. Behind and before it, spread away the verdant carpets of the two enclosed ‘greens’; above its turret and windows hang the drooping fans of elms, half disclosing and half concealing its pointed architecture; and to its door, from every direction, tend aisles of lofty trees, overhanging the paths with shadow, as if the first thought of the primitive settlers had been to create visible avenues to the house of God.” [Fig. 7]

- Trego, Charles, 1843, describing Chambersburg, PA (1843: 249)[14]

- “The Presbyterian church is much admired on account of its beautiful situation in a retired quiet spot, enveloped with trees and surrounded by a delightful green, at the west end of which is the burying ground of the congregation, and adjoining it, an ancient burying ground of the Indians.”

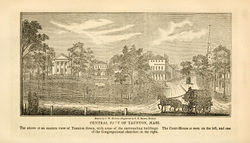

- Barber, John Warner, 1844, describing Taunton, MA (caption for pl. opp. 141, 143)[15]

"The above is an eastern view of Taunton Green, with some of the surrounding buildings. The Court-House is seen on the left, and one of the Congregational churches on the right. . .

- “The center of the main village is ornamented with an enclosed green with shade-trees, on one side of which is situated the court-house and other handsome buildings.” [Fig. 8] back up to History

- Tuthill, Louisa C. (Louisa Caroline), 1848, describing New Haven Green, New Haven, CT (1848: 319)[16]

- “The New Haven Green has been justly celebrated as one of the most beautiful public squares in this country. Its elms are remarkably fine; it has recently been enclosed with a light and tasteful iron railing, which adds much to its beauty.”

- Elder, Walter, 1849, describing Albany, NY (1849: 227)[17]

- “When in the service of Edward C. Delavan, Esq., (Champion of temperance,) we had that unique cottage at the corner of his noted flower garden in Albany, N.Y. It had three rooms on the first floor, and a good garret, and was finely shaded with a grape-vine arbour, which stretched over it; a neat bleaching green behind it, and a pump and well of ‘pure cold water’ for our private use.” back up to History

Citations

- Johnson, Samuel, 1755, A Dictionary of the English Language (1755: 1:n.p.)[18]

- “GREEN. n.s.. . .

- “2. A grassy plain.”

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828: 1:n.p.)[19]

- “GREEN, n. The color of growing plants. . .

- “2. A grassy plain or plat; a piece of ground covered with verdant herbage.

- “O’er the smooth enameled green. Milton.”

- Thomas, John J., April 1848, “The Shrubbery and Flower Garden” (Cultivator 5: 114)[20]

- “It is merely necessary to remark, that the boundary of the grounds is composed chiefly of trees and shrubs, the more central portion being devoted to flowers. The latter is a very smooth and closely shaven green, around which the walk passes, the beds being cut into the turf and raised scarcely above the surface.”

Images

Inscribed

Charles Fraser, A View in Charleston taken from Savage’s Green, 1796.

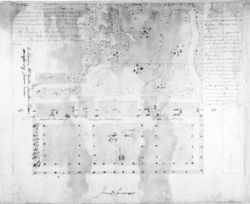

Solomon Drowne, Detailed plan of a botanic garden at Brown University, n.d. Green is inscribed at the bottom of the plan.

Associated

Amos Doolittle, A View of the Buildings of Yale College at New Haven, 1807.

John Warner Barber, “The Lower Green, or Military Common, Newark, N.J.,” in Historical Collections of the State of New Jersey (1844), pl. opp. 176.

Attributed

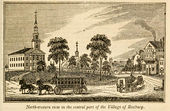

John Warner Barber, "North-western view in the central part of the Village of Roxbury," in Historical Collections, Being a general collection of interesting facts, traditions, biographical sketches, anecdotes, &c. . . ., (1844), p. 483.

L. S. Punderson, Public Square, New Haven, Ct., 1862.

Notes

- ↑ The New Haven Green is discussed at greater length in Rollin G. Osterweis, The New Haven Green and the American Bicentennial (Hamden, CT: Archon Books, 1976), 9–56, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anthony Garvan has linked the design of New Haven to two town-planning traditions: the English garrison town plans in Ireland and the Continent (such as Londonderry and Calais) and the classical principles of Vitruvius. See Anthony Garvan, Architecture and Town Planning in Colonial Connecticut (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1951), 44–49, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Records of the Colony and Plantation of New Haven, 1638–49, quoted in Osterweis 1976, 16, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Eliza Lucas Pinckney, The Letterbook of Eliza Lucas Pinckney, 1739–1762, ed. Elise Pinckney (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1972), view on Zotero.

- ↑ James Birket, Some Cursory Remarks (Made by James Birket in His Voyage to North America 1750–1751) (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1916), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Hannah Callender Sansom, The Diary of Hannah Callender Sansom: Sense and Sensibility in the Age of the American Revolution, ed. Susan E. Klepp and Karin Wulf (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2010), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 William Strickland, Journal of a Tour in the United States of America, 1794–1795, ed. J. E. Strickland (New York: New-York Historical Society, 1971), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Timothy Dwight, Travels in New England and New York, 4 vols. (New Haven, CT: Timothy Dwight, 1821), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Benjamin Silliman, Remarks Made on a Short Tour between Hartford and Quebec, in the Autumn of 1819 (New Haven, CT: S. Converse, 1824), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Martha Ogle Forman, Plantation Life at Rose Hill: The Diaries of Martha Ogle Forman, 1814–1845 (Wilmington, DE: Historical Society of Delaware, 1976), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Frederick Douglass, My Bondage and My Freedom, ed. William L. Andrews (1855; repr., Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1987), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Nehemiah Adams, The Boston Common, or Rural Walks in Cities (Boston: George W. Light, 1838), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Nathaniel Parker Willis, American Scenery, or Land, Lake and River Illustrations of Transatlantic Nature, 2 vols. (1840; repr., Barre, MA: Imprint Society, 1971), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles B. Trego, A Geography of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia: Edward C. Biddle, 1843), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Warner Barber, Historical Collections, Being a General Collection of Interesting Facts, Traditions, Biographical Sketches, Anecdotes, &c., Relating to the History and Antiquities of Every Town in Massachusetts, with Geographical Descriptions (Worcester, MA: Warren Lazell, 1844), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Louisa C. Tuthill, History of Architecture, from the Earliest Times. . . (Philadelphia: Lindsay and Blakiston, 1848), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Walter Elder, The Cottage Garden of America (Philadelphia: Moss, 1849), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language: In Which the Words Are Deduced from the Originals and Illustrated in the Different Significations by Examples from the Best Writers, 2 vols. (London: W. Strahan for J. and P. Knapton, 1755), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John J. Thomas, “The Shrubbery and Flower Garden,” Cultivator, a Monthly Publication, Devoted to Agriculture 5, no. 4 (April 1848): 114–16, view on Zotero.