Gate/Gateway

History

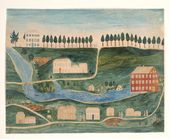

Ubiquitous in the American landscape, fences, walls, and hedges required openings or passages. As Noah Webster (1828) stated, a gate could refer to either the opening or the elements fitted into it. A distinction was sometimes made identifying a gateway as the opening and a gate as the elements that closed the opening. The terms, however, were often interchangeable. The gate and gateway served both practical and symbolic functions in landscape design and were related to other features, such as special stairs, stiles, posts, or turnstiles that regulated access to pedestrian or horse traffic. The positioning of these features was an essential part of a landscape design’s circulation pattern, as well as its visual organization. As a barrier, the gate or gateway provided protection and privacy, and as a passageway it provided access and control of foot and vehicular traffic. But such access points also signified the social importance of entrances and passageways, whether to an estate (as at Montgomery Place in Dutchess County, New York) or a holy ground (as at the “holy mount” in New Lebanon, New York). In the landscape design of residences, the gate or gateway often presented visitors with their first impression of an estate and conveyed the passage between public and private realms. When, in 1720, William Byrd II greeted honored guests at Westover, Virginia, on the James River, he “received them at the outer gate.” In images of residences, the gate was often placed in the foreground of the picture and was often shown open, possibly as a symbol of hospitality. In both public and private landscapes, the gate was often sited on the central axis of a building, marking the main approach, framing the building’s front façade and doorway, and directing views from the house into the distant landscape. A gate both enabled and marked the transition from one area to another, such as between yards devoted to different activities, between a work space and a more ornamental garden or front lawn, or between different sections of a garden.

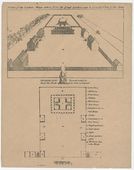

In spaces such as parks, public gardens, and commons, gates marked public entrances. Samuel McIntire’s design (1802) for the west gate of Washington Square in Salem, Massachusetts, included a wooden archway with a carved gilded eagle resting atop a medallion of Gen. George Washington. In 1790, at Gray’s Garden in Philadelphia the public similarly entered though “an elegant arched gate. . . guarded by the figure of a satyr.” A watercolor painting of City Hall Park in New York around 1825 depicts two gates in the iron fence that are noteworthy not only for their elaborate gateposts but also because they are mounted on wheels to facilitate movement [Fig. 1].

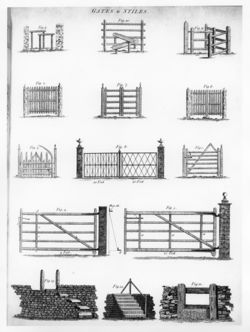

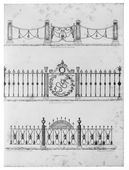

Depending on its context, gate or gateway design ranged from simple utility to elaborate ornamentation [Fig. 2]. J. C. Loudon's 1826 discussion of the gate exemplified the range of possible styles and materials. Whatever the style, the construction of a gate necessitated a balance between strength and lightness so that it might serve this purpose with a minimum of support. According to Loudon, a gate placed between pastures or animal yards needed only to be a simple wooden frame and boards strong enough to restrain the animals. In contrast, Benjamin Henry Latrobe's 1798 plan for the State Penitentiary in Richmond, Virginia, included specifications for a gate of the “utmost highth.”

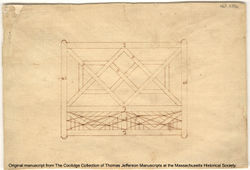

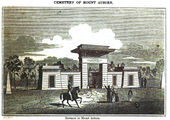

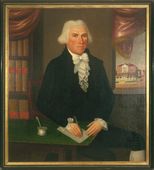

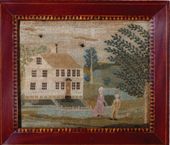

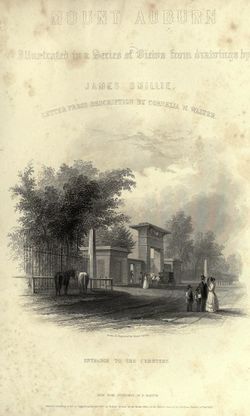

The decorative treatment of gates varied, as Loudon noted, “according to the character of the scene,” and there were numerous published designs for a variety of styles [Fig. 3]. Thomas Jefferson drew a gate [Fig. 4] inspired by the Chinese lattice popularized in books such as William Chambers’s Dissertation on Oriental Gardening (1772).[1] Mount Auburn and Lowell Cemeteries in Massachusetts, and New Haven Burying Ground in Connecticut, included entrance gates in an Egyptian style whose “imposing. . . massiveness” and “eternal duration” were symbolically appropriate for the sites. In contrast, C. M. Hovey in 1841 criticized the gate at Downing's residence for its “grecian” style because it contrasted to the Gothic architecture of the main house. Highly visible gates made suitable niches or platforms for statuary, urns, crests or other decorative sculpture and carving. In Boston in 1721 Judge Samuel Sewall decorated his gate leading to the street with carved cherubim heads. Latrobe reported in 1806 that an Italian sculptor was at work on a “Free Eagle” and “Colossal” for the Navy Yard in Washington, DC. William Dering’s 1754 portrait of George Booth depicted the sitter in front of a grand entrance gate flanked by statues [Fig. 5].[2] With the development of cast iron, decorative work on gates, such as those for rural cemetery family plots at Mount Auburn and at Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York, became more affordable and abundant (see Fence and Statue).

Gates were often painted in colors contrasting with an adjacent wall or fence. As Humphry Repton noted, this treatment emphasized the principle entrance gate, assuring that “no one may mistake it.” Marie L. Pilsbury’s Louisiana Plantation Scene (c. 1830) shows how painted gates stood out in the landscape [Fig. 6].

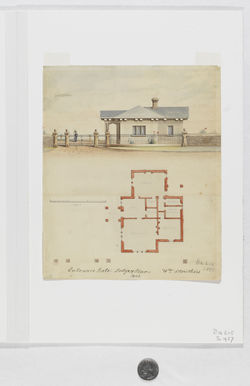

The gates of large estates, institutions, and rural cemeteries sometimes also incorporated a lodge or gatehouse such as those illustrated by William Struthers (1842) [Fig. 7], and described by James Thatcher (1830) at Hyde Park and Thomas Kirkbride (1848) at the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane in Philadelphia. In addition to their enhancement of the entranceway, these gate lodges served as residences for the gatekeeper.[3]

—Elizabeth Kryder-Reid

Texts

Usage

- Byrd, William, II, August 9, 1720, describing Westover, seat of William Byrd II, on the James River, VA (1958: 437)[4]

- “I got everything in great order long before the Governor came. . . and there came with him Colonel Ludwell, the Secretary and his son, and John Randolph. I received them at the outer gate and about six we went to dinner and had four dishes of courses.”

- Sewall, Judge Samuel, January 21, 1721, describing his garden in Boston, MA (quoted in Lockwood 1931: 1:27)[5]

- “Quickly after the wind rose to a prodigious height. . . It blew down the southernmost of my cherubim’s heads at the Street Gates.”

- Ball, Joseph, February 1734, describing a property in Virginia (Library of Congress, Joseph Ball Letterbook)

- “I would have a new Great Gate made out of the Stuff that I have ready Sav’d for that purpose: The Back & fore parts, that the the [sic] bars are to be mortois’d into, to be of Locust; which must be faln, and ly to Season awhile, to keep it from splitting. And let it be Cross-brac’d, and pinn’d Cleaverly to keep it from Saging; and let there be a Good Latch & Catch put as Low as the old one, to keep it fast, that hogs may neither go in nor out: and give charge, that it be always kept Shut: and indeed it must be so hung as the old one was, and kept Greas’d, that it may Shut itself. And I would have the old Gate, hinges and all, well mended and sent up into the Forrest, and well hung there, with the posts Large, and a Crosspeice at top; and sat, at least, three foot in the Ground; and well [illeg.] and a Large Cill laid in the Ground; the upper Side not to be above two Inches above Ground.”

- Bartram, John, July 18, 1739, describing Westover, seat of William Byrd II, on the James River, VA (1992: 121)[6]

- “Col Byrd is very prodigal in Gates roads walks hedges & seeders [cedars] trimed finely & A little green house with 2 or 3 [orange] trees. . .”

- Anonymous, 1769, describing in the Chester Parish Vestry Book a parish churchyard in Kent County, MD (quoted in Lounsbury 1994: 158)[7]

- “[A carpenter was] to make one good framed double gate each frame with good pine paling the said Gate to be hung to good locust posts with good iron hinges with an iron latch and ketch.”

- Constantia [Judith Sargent Murray], June 24, 1790, “Description of Gray’s Gardens, Pennsylvania” (Massachusetts Magazine 3: 414)[8]

- “If we proceed straight forward, we pass through an elegant arched gate, which seems to be guarded by the figure of a satyr, extremely well painted.”

- Latrobe, Benjamin Henry, November 1798, describing a prison at Richmond, VA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “The front Walls were built as high as the Ground line, and considerable progress had been made in erecting the Gate. . . The Gateway is carried up to its utmost highth, and will be perfectly finished during the winter. It contains two lodges for a porter and Guards, and on each Wing, a bath and storeroom, on the East for the Women, on the West, for the Men.”

- Bentley, William, 18 May 1802, describing Salem Common (later Washington Square), Salem, MA (1962: 2:431)[9]

- “18. . . . It is said that it is agreed to call the Common, which now is almost levelled [sic]& railled [sic], Washington Square. This is better than walking in common.

- “21. Mr. Hunt has succeeded in levelling the Common. The Subscription is not sufficient to answer all demands & is to be renewed. Col. Derby deserves all praise.

- “22. Subscription for elegant gates to the Washington Square, alias Common.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, c. 1804, describing improvements for Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, VA (Massachusetts Historical Society, Coolidge Collection)

- “A gate at the entrance of the garden, having a green house below.”

- Latrobe, Benjamin Henry, 1806, describing a sculpture created for the Navy Yard, Washington, DC (quoted in Lounsbury 1994: 158)[7]

- “[Italian sculptor Franzoni is] now engaged in a Free Eagle, also Colossal for the Gate of the Navy Yard.”

- Drayton, Charles, November 2, 1806, describing The Woodlands, seat of William Hamilton, near Philadelphia, PA (1806: 54—55)[10]

- “A common post & rail fence, [not in sight from the house,] winds from the public road gate, & joins to the garden fence, which is a double sloped ditch, with a low fence of posts & 3 rails. . .

- “. . . One is led into the garden from the portico, to the east or lefthand. or from the park, by a small gate contiguous to the house, traversing this walk, one sees many beauties of the landscape—also a fine statue, symbol of Winter, & age,—& a spacious Conservatory about 200 yards to the West of the Mansion.”

- Hening, William Waller, 1819–23, describing an act of the Virginia General Assembly (quoted in Lounsbury 1994: 158)[7]

- “[A 1667 act of the Virginia General Assembly required] that every person haveing a plantation shall, at the most plaine and convenient path that leades to his house, make a gate in his ffence for the convenience of passage of man and horse to his house about their occasions at the discretion of the owners.”

- Silliman, Martha Trumbull, September 1, 1821, describing Monte Video, property of Daniel Wadsworth, Avon, CT (quoted in Saunders and Raye 1981: 20)[11]

- “The place is a great deal handsomer than I expected. The buildings are all Gothic. First there is Uncles beautiful house; 2d the tower, 3d the cottage & the barns 4th the boat house & 5th the bathing house 6th a grape house 7th an ice house & 8th the bee house & a Gothic gate.”

- Douglass, Frederick, 1825, describing Wye House, estate of Col. Edward Lloyd, Talbot County, MD (1855; repr., 1987: 47)[12]

- “The carriage entrance to the house was a large gate, more than a quarter of a mile distant from it.”

- Mitchell, T., March 10, 1826, describing Hermitage, estate of Andrew Jackson, Nashville, TN (Hermitage Collections, Andrew Jackson Papers)

- “To Repairing Garden 106 pannels

- at 37 1/2 cents pr pannel

- Making Garden Gate $39.75

- 7.50

- 45.25

- Galt, William R., Fall 1828, describing Hermitage, estate of Andrew Jackson, Nashville, TN (Hermitage Collections, Andrew Jackson Papers)

- “We reached the Hermitage at about one o’clock P.M. We rode up to the gate, which was opened by a servant, who took our horses, directing us to go straight to the front door of the Great House. . . The approach to the Hermitage was by no means picturesque. There were two gates, a broad one for carriages, and a narrow one, to the east of the former, for men on horseback or wayfarers. As travelers approached from the South, they could see only the upper tier of windows of the Hermitage, the rest of the house being concealed from view by a rising ground in front.”

- Thacher, James, December 3, 1830, “An Excursion on the Hudson,” describing Hyde Park, seat of David Hosack, on the Hudson River, NY (New England Farmer 9: 156)[13]

- “From the turnpike road there are two gates of entrance into the premises, about half a mile from each other, and a porter’s lodge is connected with each gate. . . The entrance gate is finished in a very neat and imposing style of architecture. Mr Thompson of New York, is the skilful [sic] architect employed in the construction of these buildings. The south lodge, connected with a neat gateway, with the improvements of the surrounding grounds, present a very picturesque appearance.”

- Dearborn, H. A. S., September 30, 1831, describing Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, MA (quoted in Ward 1831: 46–47)[14]

- “Models and drawings of the Egyptian gateways, and of a Gothic tower, and a Grecian tower, one of which is proposed to be erected on the highest hill, have been made, and are offered for examination. . .

- “As the tract which has been solemnly consecrated, by religious ceremonies, as a burial-place forever, is so abundantly covered with forest trees, many of which are more than sixty years old, it only requires. . . gateways and appropriate edifices erected, to put the grounds in a sufficiently complete state for the uses designed, and to render them at once beautiful and interesting.”

- Latrobe, John H. B., 4 August 1832, describing Montpelier, plantation of James Madison, Montpelier Station, VA (quoted in Semmes 1917: 239)[15]

- “Mr. Madison resides about five miles from the Court House. . . You leave the Piedmont road about a mile from Montpelier and, turning to the left, pass through a dense forest for a considerable distance and until you descry at the end of a straight alley in the wood a high red gate, hung upon white posts. Entering this, you find yourself in a clearing, surrounded on all sides by the forest, and perhaps a quarter of a mile in diameter. Close against the opposite woods, you see the mansion of Mr. Madison. . . You now pass through a very large field. . . Another red gate admits you into the plantation, which more immediately belongs to the establishment. Stopping at a small gate in a very handsome paling, you ascend the gravel walk and find yourself under the portico of Montpelier.”

- Ingraham, Joseph Holt, 1835, describing the villas and gardens along the Mississippi River (1835: 1:230)[16]

- “An hour’s drive. . . brought us in front of a charming residence situated at the head of a broad, gravelled avenue, bordered by lemon and orange trees, forming in the heat of summer, by arching naturally overhead, a cool and shady promenade. We drew up at the massive gate-way and alighted.”

- Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), November 1841, “Select Villa Residences,” describing Highland Place, estate of A. J. Downing, Newburgh, NY (Magazine of Horticulture 7: 406)[17]

- “Commencing at the entrance gate, which we shall only stop to find fault with for the want of keeping in its Grecian style, with the Gothic architecture of the house, we pass by the flower garden, green-house, and a portion of the pleasure-ground, and arrive at the house.”

- W., February 1842, describing Lowell Cemetery, Lowell, MA (Magazine of Horticulture 8: 50)[18]

- “The plan of the gateway is designed upon the ancient Egyptian style of architecture, consisting of an elevation similar on both sides, which serve as gate piers, to which are hung gates folding in the centre. Each pier rests upon a base about five feet square, surmounted with a plain massive capital; the height of the elevation, from the ground to the apex of the wreathed head of the capitals, is twenty feet: upon the interior face of these piers, and next the gate, are pilasters supporting the Egyptian arch, which is twelve feet wide.”

- Anonymous, 28 July 1842, “Words of a Solomon and Sacred Roll. . . ,” describing New Lebanon, NY (Western Reserve Historical Society, Shaker Manuscript Collection)

- “Upon my holy Mount there shall be two large gates, 12 feet wide. And the entrance upon the holy ground I will now change; for my holy & sacred ground must be a place of perfect order, beauty and neatness.

- “The place for the congregation to enter shall be in the middle of the west end; here they shall enter the most holy ground and proceed to the altar brethren. . . The other gate shall be at the South east corner; this shall also be twelve feet wide. And it is my will, that those of the gathering order prepare and make these places of entrance upon my holy ground, for they stand as the door for souls to enter my holy and purifying work.”

- Rusticus [pseud.], August 1846, “Design for a Rustic Gate” (Horticulturist 1: 72)[19]

- “Dear Sir—I send you a little sketch of a rustic gate which I have erected this season, and which, though very simple, has been a good deal admired by those who have seen it.

- “The roof, or canopy over it, is, as I have ascertained in a previous case, a most useful addition, since by guarding the gate itself to a considerable degree from the storms, it prevents it from getting out of repair.

- “This gate stands at an angle in the boundary lines, at the entrance to a little wood. Its rustic and sylvan character agrees well with the situation in which it stands.” [Fig. 8]

- Cleaveland, Nehemiah, 1847, describing Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, MA (1847: 17–18)[20]

- “Originally the portal was of wood, rough-cast, in imitation of stone, and the connected paling on either side was of wood also. The lofty entrance-gate has now been reconstructed, in granite, in the same style of architecture as at first—the Egyptian—and it presents to the beholder an imposing structure, the very massiveness and complete workmanship of which, insures an almost eternal duration. It is less heavy, however, than the common examples of that style.” [Fig. 9]

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, October 1847, describing Montgomery Place, country home of Mrs. Edward (Louise) Livingston, Dutchess County, NY (quoted in Haley 1988: 45)[21]

- “On the east it [the natural boundary of the estate] touches the post road. Here is the entrance gate, and from it leads a long and stately avenue of trees, like the approach to an old French chateau.”

- Kirkbride, Thomas S., April 1848, describing the pleasure grounds and farm of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, Philadelphia, PA (American Journal of Insanity 4: 347)[22]

- “The entrance to the enclosure is through a handsome gate-way, on the west side of which is the Gate-keeper’s Lodge, and on the opposite side is a room for laying out the dead, access to which may be had from within as well as from without the pleasure grounds.”

Citations

- Johnson, Samuel, 1755, A Dictionary of the English Language (1755: 1:n.p.)[23]

- “GATE. n.s. [. . . Saxon.] . . .

- “2. A frame of timber upon hinges to give a passage into inclosed grounds. . .

- “3. An avenue; an opening.”

- Repton, Humphry, 1803, Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1803: 13, 144, 147–48)[24]

- “The entrance gate should not be visible from the mansion, unless it opens into a court yard. . .

- “If the entrance to a park be made from a town or village, the gate may with great propriety be distinguished by an arch. . .

- “As an entrance near a town, I prefer close wooden gates, for the sake of privacy, except where the view is only into a wood, and not into the open lawn.

- “The gates should be of iron, or close boards, if hanging to piers of stone or brick work; otherwise an open or common field gate of wood appears mean, or as if only a temporary expedient.

- “If the gates are of iron, the posts or piers ought to be conspicuous, because an iron gate hanging to an iron pier of the same colour, is almost invisible; and the principle entrance to a park should be so marked that no one may mistake it.

- “If the entrance gate be wood, it should for the same reason be painted white, and its form should rather tend to shew its construction, than aim at fanciful ornament of Chinese, or Gothic.”

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826: 337, 352, 354–55)[25]

- “1712. Entrance lodges and gates more properly belong to architecture than gardening. But, as in small places, they are sometimes designed by the garden-architect, or landscape-gardener, a few remarks may be of use. . . A handsome architectural entrance is but a poor compensation for its want of harmony with the mansion. . .

- “1794. The gate is of various forms and materials, according to those of the barrier of which it constitutes a part. In all gates, the essential part of the construction, or those lines which maintain its strength and position, and facilitate its motion, are to be distinguished from such. . . as serve chiefly to render it a barrier, or as decorations. Thus a gate with a raised top or head (fig. 321.) is almost always in bad taste, because at variance with strength; while the contrary form (fig. 320.) is generally in good taste, for the contrary reason. In regard to strength, the nearer the arrangement of rails and bars approaches in effect to one solid lamina, or plate of wood or iron, of the gate’s dimensions, the greater will be the force required to tear or break it in pieces. But this would not be consistent with lightness and economy, and, therefore, the skeleton of a lamina is resorted to, by the employment of slips or rails joined together on mechanical principles; that is, on principles derived from a mechanical analysis of strong bodies. . . [Fig. 10]

- “1800. Gates, as decorations, may be classed according to the prevailing lines, and the materials used. Horizontal, perpendicular, diagonal, and curved lines, comprehend all gates, whether of iron or of timber, and each of these may be distinguished more or less by ornamental parts, which may either be taken from any of the known styles of architecture, or from heraldry or fancy.

- “1801. The published designs for gates are numerous, especially those for iron gates; for executing which, the improvements made in casting that metal in moulds afford great facilities. By a judicious junction of cast and wrought iron, the ancient mode of enriching gates with flowers and other carved-like ornaments might be happily reintroduced.

- “1802. Gates in garden-scenery, where architectural elegance is not required to support character, simple or rustic structures. . . wickets, turn-stiles, and even moveable or suspended rails, like the German schlagbaum. . . may be introduced according to the character of the scene.” [Fig. 11]

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828: 1:n.p.)[26]

- “GATE, n. [Sax. gate, geat; Ir. greata; Scot. gait; The Goth. gatwo, Dan. gade, Sw. gata, G. gasse, Sans. gaut, is a way or street. In D. gat is a gap or channel. . .]

- “1. A large door which gives entrance into a walled city, a castle, a temple, palace or other large edifice. It differs from door chiefly in being larger. Gate signifies both the opening or passage, and the frame of boards, planks or timber which closes the passage.

- “2. A frame of timber which opens or closes a passage into any court, garden or other inclosed ground; also, the passage.

- “3. The frame which shuts or stops the passage of water through a dam into a flume.

- “4. An avenue; an opening; a way. Knolles.”

- Hooper, Edward James, 1842, The Practical Farmer, Gardener and Housewife (1842: 129–30)[27]

- “GATES. In their construction the great object is to combine strength with lightness. The gate post should be very large for steadiness. The timber should be well seasoned. Gates should be light in the fore parts.”

- Ranlett, William H., 1847–49, The Architect (1849: 2:43)[28]

- “PLATE 30.—Elevations and profiles of fences in six different styles, drawn to a scale of 3/4 of an inch to a foot ; the balusters in Fig. 1,2,3, and 4,1/2 inches square ; Fig. 6, 3 inch by 3/4 in. ; the g[ ]te and corner pos s cased and capped—all thee intervening posts to be squared and made smooth for painting—the gates made like the frames, and hung by heavy straps, hooks and bol[ ]s and secured by spring latches.

Images

Inscribed

Anonymous, A View of the Orphan House taken from the Great Garden-Gate & Ground Platt of the Same, 1739.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, "Principal Story of a Military School," 1800.

Thomas Jefferson, Plan of the grounds at Monticello, 1806. "gate" inscribed to the left.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Plan of the west end of the public appropriation in the city of Washington, called the Mall, as proposed to be arranged for the site of the university, 1816. Gate inscribed at center right.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Project for the Principal Gates of the Public Square at New Orleans, c. 1819—20.

J. C. Loudon, Examples of gates, in An Encyclopædia of Gardening, (1826), 353, figs. 319–21.

J. C. Loudon, A gate in a simple or rustic structure, in An Encyclopædia of Gardening, (1826), 354, fig. 326.

Anonymous, Design for a Rustic Gate, in Rusticus, “Design for a Rustic Gate,” Horticulturist 1, no. 2 (August 1846): 73.

Frances Palmer, “Ground Plot,” in William H. Ranlett, The Architect (1851), vol. 2, pl. 29. "M M M, gates made and hung to stone posts."

Frances Palmer, Elevations and profiles of wood fences, in William H. Ranlett, The Architect (1851), vol. 2, pl. 30.

Associated

Thomas Jefferson, Drawing for a gate in Chinese lattice at Monticello, c. 1771.

George Isham Parkyns, Mount Vernon, 1795.

George Ropes, Salem Common on Training Day, 1808.

Charles Willson Peale, Ground plot of Belfield, 1810.

Anne-Marguerite Hyde de Neuville, Entrance Gate to the White House Garden, Washington, D.C., 1818.

Anonymous, “Entrance to Mount Auburn,” in American Magazine of Useful and Entertaining Knowledge 1, no. 1 (September 1834): 9.

William Strickland, Elevation of the Entrance to Laurel Hill Cemetery, c. 1836.

Thomas U. Walter, Plan of Entrance to Laurel Hill Cemetery, May 14, 1836.

John Caspar Wild, Laurel Hill Cemetery, Philadelphia, 1838.

John Warner Barber, “Entrance to Mount Auburn Cemetery,” in Historical Collections, (1844), 361.

John T. Hammond (engraver), Plan of the Laurel Hill Cemetery, near Philadelphia [detail], c. 1845.

James Smillie, “Entrance to the Cemetery,” in Cornelia W. Walter, Mount Auburn Illustrated (1847; repr., 1850), title page.

A. J. Downing, “Presidents Arch at the end of Penna Avenue,” 1851.

Attributed

Anonymous, Fairhill, The Seat of Isaac Norris Esq., 18th century.

William Tennant, A North-West Prospect of Nassau Hall, with a Front View of the Presidents House in New-Jersey, Princeton College, 1764.

Eliza Coggeshall, Brick House with Flowers and Birds on Fence, 1784.

John Nancarrow, "Plan of the Seat of John Penn, jun:r Esq:r in Blockley Township and County of Philadelphia," c. 1785. A gate is visible near the point indicated with the letter "f".

Jonathan Budington, View of the Cannon House and Wharf, 1792.

Rufus Hathaway, A View of Mr. Joshua Winsor's House &c., 1793-95.

David Leonard, A S. W. view of the College in Providence, together with the President’s House & Gardens, c. 1795.

Anne Pope, Beige House, Birds Flying Over with Foreyard, 1796, in Sotheby’s New York, Important American Schoolgirl Embroideries: The Landmark Collection of Betty Ring (January 2012), p. 15.[29]

Joseph Meigs, Copy of the Plan of the New Haven Burying Ground, 1797.

Clarissa Deming, Map of Deming Orchard, after 1798.

Amy Cox, attr., Box Grove, c. 1800.

Jonathan Budington or Dr. Francis Forgue, attr., View of Main Street in Fairfield, Connecticut, c. 1800.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, North Elevation of a Military Academy, 1800.

Anonymous, New England Country Seat, c. 1800—20.

Anonymous (artist), George Hayward (lithographer), Vauxhall Garden 1803, 1856.

Francis Guy, Bolton, view from the South, c. 1805.

Francis Guy, Mount Deposit from the North, 1805.

Marie L. Pilsbury, Louisiana Plantation Scene, 1820.

Anne-Marguerite Hyde de Neuville, Washington City, 1821.

Arthur J. Stansbury, City Hall Park From the Northwest Corner of Broadway and Chambers Street, c. 1825.

Anonymous, The Plantation, c. 1825.

Alexander Jackson Davis, Castle Garden, N. York, c. 1825—1828. Gate is seen on the left.

J. C. Loudon, Examples of Treillage-Work, in An Encyclopædia of Gardening (1826), 355, fig. 328.

Anthony Imbert after Alexander Jackson Davis, View of the Battery and Castle Garden, 1826-28.

Alexander Jackson Davis, Ithiel Town, and James Dakin, New York University, Washington Square, 1833.

John Notman, Plan of the Lauren Hill Cemetery. Near Philadelphia, 1839. Gateway to Laurel Hill.

M. Schmitz (artist), Thomas S. Sinclair (lithographer), John B. Colahan (surveyor), Map of Washington Square, Philadelphia, 1843.

George W. Stilwell and Cornell & Jackson, Patterns of railings at Greenwood Cemetery, in Nehemiah Cleaveland, Green-Wood Illustrated (1847), pl. after 94.

Charles H. Wolf, attr., Pennsylvania Farmstead with Many Fences, c. 1847

Anonymous (artist) and H. Austin (architect), Entrance to the Cemetery at New Haven, in Louisa C. Tuthill, History of Architecture (1848), 336, pl. 33.

James Smillie (artist), Sarony & Major (printers), View of Union Park, New York, from the head of Broadway, 1849.

Edwin Whitefield, View of Hartford, CT. From the Deaf and Dumb Asylum, 1849.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, “Greenspring, home of William Ludwell Lee, James City County, Virginia,” n.d.

Notes

- ↑ William Howard Adams, ed., The Eye of Thomas Jefferson (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1976), 334, view on Zotero.

- ↑ David S. Bundy, comp., Painting in the South, 1564–1980 (Richmond: Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, 1983), 181, view on Zotero.

- ↑ James O’Gorman et al., Drawing Toward Building: Philadelphia Architectural Graphics, 1732–1986 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press for the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 1986), 88, view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Byrd, The London Diary, 1717–1721, and Other Writings, ed. Louis B. Wright and Marion Tinling (New York: Oxford University Press, 1958), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alice B. Lockwood, ed., Gardens of Colony and State: Gardens and Gardeners of the American Colonies and of the Republic before 1840, 2 vols. (New York: Charles Scribner’s for the Garden Club of America, 1931), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Bartram, The Correspondence of John Bartram, 1734–1777, ed. Edmund Berkeley and Dorothy Smith Berkeley (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1992), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Carl R. Lounsbury, ed., An Illustrated Glossary of Early Southern Architecture and Landscape (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Constantia [Judith Sargent Murray], “Description of Gray’s Gardens, Pennsylvania,” Massachusetts Magazine, or, Monthly Museum of Knowledge and Rational Entertainment 7, no. 3 (July 1791): 413–17, view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Bentley, The Diary of William Bentley, D.D., Pastor of the East Church, Salem, Massachusetts (Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1962), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Drayton, “The Diary of Charles Drayton I, 1806,” Drayton Papers, MS 0152, Drayton Hall, SC, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Richard Saunders and Helen Raye, Daniel Wadsworth, Patron of the Arts (Hartford, CT: Wadsworth Atheneum, 1981), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Frederick Douglass, My Bondage and My Freedom, ed. William L. Andrews (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1987), view on Zotero.

- ↑ James Thacher, “An Excursion on the Hudson. Letter II,” New England Farmer, and Horticultural Journal 9, no. 20 (December 3, 1830): 156–57, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Malthus A. Ward, An Address Pronounced Before the Massachusetts Horticultural Society (Boston: J. T. & E. Buckingham, 1831), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John E. Semmes, John H. B. Latrobe and His Times, 1803–1891 (Baltimore, MD: Norman, Remington, 1917), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Joseph Holt Ingraham, The South-West, 2 vols. (New York: Harper, 1835), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Mason Hovey, “Select Villa Residences, with Descriptive Notices of Each; Accompanied with Remarks and Observations on the Principles and Practice of Landscape Gardening: Intended with a View to Illustrate the Art of Laying Out, Arranging, and Forming Gardens and Ornamental Grounds,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 7, no. 11 (November 1841): 401–11, view on Zotero.

- ↑ W., “An Account of the Lowell Cemetery, Its Situation, Historical Associations, and Particular Description,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 8, no. 2 (February 1842): 47–50, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Rusticus [pseud]., “Design for a Rustic Gate,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 1, no. 2 (August 1846): 72–73, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Nehemiah Cleaveland, Green-Wood Illustrated (New York: R. Martin, 1847), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jacquetta M. Haley, ed., Pleasure Grounds: Andrew Jackson Downing and Montgomery Place (Tarrytown, NY: Sleepy Hollow Press, 1988), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas S. Kirkbride, “Description of the Pleasure Grounds and Farm of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, with Remarks,” American Journal of Insanity 4, no. 4(April 1848): 347–54, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language: In Which the Words Are Deduced from the Originals and Illustrated in the Different Significations by Examples from the Best Writers, 2 vols. (London: W. Strahan for J. and P. Knapton, 1755), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Humphry Repton, Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (London: Printed by T. Bensley for J. Taylor, 1803), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, 4th edn (London: Longman et al, 1826), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Edward James Hooper, The Practical Farmer, Gardener and Housewife, or Dictionary of Agriculture, Horticulture, and Domestic Economy (Cincinnati, Ohio: George Conclin, 1842), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William A. Ranlett, The Architect: A Series of Original Designs, for Domestic and Ornamental Cottages and Villas, Connected with Landscape Gardening, Adapted to the United States: Illustrated by Drawings of Ground Plots, Plans, Perspective Views, Elevations, Sections, and Details, 2 vols. (New York: William H. Graham et al., 1847–49), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Sotheby’s New York, Important American Schoolgirl Embroideries (January 2012), view on Zotero.