Rustic style

History

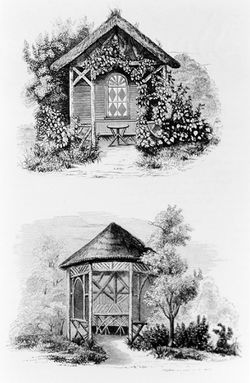

The term rustic was most commonly applied to garden architecture and decorative objects characterized by material or treatment of material that imparted a sense of the primitive, the unfinished, or, as J. C. Loudon wrote, the “common.” Rustic arbors, arches, baskets, bridges, columns, gates [Fig. 1], seats, summerhouses, [Fig. 2], and other structures were made from rough materials such as wood with the bark left on or from saplings. In some cases, as at Economy, Pennsylvania, roughly hewn stone was used in the construction of a rustic hermitage. In his extensive description of rustic work (1848–49), A. J. Downing included the moss-house (a framework covered with living mosses) as another type of rustic pavilion. Thatch for roofing also was frequently used for rustic structures, as Loudon prescribed in some of his designs [Fig. 4]. Downing said that structures made of these materials “appear but one remove from natural forms” and so were in harmony with their surroundings. He contrasted the “mural and highly artistical vase and statue” as most properly accompanying the beautiful landscape garden, with the rustic as the most fitting decoration of the picturesque landscape garden. Several garden writers recommended locating rustic artifacts and structures away from the highly finished villa, in secluded spots. As some images illustrate, rustic embellishment often was situated among heavy plantings or in densely wooded areas [Figs. 4–6].

Loudon and Downing, however, both occasionally endorsed the juxtaposition of styles. For example, Loudon depicted a Grecian urn under a rustic arch, because it could produce “a striking contrast.” The rustic was to be used, we are told by Loudon, “to attract attention” amidst otherwise “refined and artistical scenery, whether in the irregular or geometric styles.”

The rustic style suited the picturesque mode of landscape gardening (also known as the modern or natural style), which derived from the aesthetic discovery of the countryside and rural life in the late 18th and 19th centuries.[1] Loudon’s extensive discussion of the rustic exemplified this cultural trend. At times, the terms “grotesque” and “rustic” were used synonymously to denote an unrefined, common appearance. Loudon also used the words “rural” and “indigenous” as alternatives to “rustic,” to refer to the imitation of local scenery. The modern style dominated landscape taste in America after the Revolution, as illustrated by the numerous 19th-century descriptions and citations of the rustic that are included in this study.

Downing, who played an important role in the popularization of the “rural taste” in America, championed rusticity in the embellishment of gardens and homes. His publications provided many examples of rustic furniture and architecture, as well as advice on their materials, siting, and construction. He depended frequently upon Loudon’s publications, which he credited as his source. In an issue of the Horticulturist (January 1850), the writer Jeffreys, from New York, associated rusticity with rural taste: “A true country house should also have some appearance of rusticity—not vulgarity—but a keeping with all which surround it. Not castellated, nor magnificent; neither ostentatious nor pretending, but plain, dignified, quiet, and unobtrusive; yet of ample dimensions, and exceeding convenience. Then, in park or lawn, on hill or plain, flanked with mossy foliage, and well kept grounds, it becomes a perfect picture in a finished landscape.” To this pronouncement, the editor, Downing, added in brackets “[m]ost excellent and sensible.”[2]

—Therese O’Malley

Texts

Usage

- S., J. W., February 1832, describing André Parmentier’s horticultural and botanical garden, Brooklyn, NY (Gardener’s Magazine 8: 72)[3]

- “To the left of the garden, an avenue leads to a rustic arbour, in the grotesque style, constructed of the crooked limbs of trees in their rough state, covered with bark and moss: from the top of this arbour a view of the whole garden and the surrounding scenery is obtained; including Staten Island, the Bay, Governor’s Island, and the city of New York.”

- Wailes, Benjamin L. C., December 29, 1829, describing Lemon Hill, estate of Henry Pratt, Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Moore 1954: 359)[4]

- “Several summer houses in rustic style are made by nailing bark on the outside & thaching the roof. There is also a rustic seat built in the branches of a tree, & to which a flight of steps ascend. In one of the summer houses is a Spring with seats arrond it.”

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1838, describing the grounds of the Lawrencian Villa, residence of Mrs. Lawrence, Drayton Green, near London (1838: 581)[5]

- “The next scene of interest is the Italian walk, arrived at the point 8, in which, and looking back towards the paddock, we have, as a termination to one end of that walk, the rustic arch and vase. . . [Fig. 7]

- Buckingham, James Silk, April 1840, describing the garden of Father George Rapp, Economy, PA (1842: 2:227)[6]

- “At one quarter of the garden, Mr. Rapp pointed to a circular building of rustic masonry, composed of very large unhewn stones, rudely piled on each other, and covered with a sloping roof of straw-thatch, with rough bark door and portals, resembling the buildings called hermitages, often found in English grounds.” [Fig. 8]

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, June 13, 1848, describing Highland Place, estate of A. J. Downing, Newburgh, NY (quoted in Haley 1988: 33–34)[7]

- “I have also been making some little improvements in my own garden—and especially building a rustic summer house which we call the ‘hermitage,’ and which I think is so much in your own taste that I should be heartily glad to show it to you.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1849, describing André Parmentier’s horticultural and botanical garden, Brooklyn, NY (1849; repr., 1991: 459–60)[8]

- “Those of our readers who may have visited the delightful garden and grounds of M. Parmentier, near Brooklyn, some half a dozen years since, during the lifetime of that amiable and zealous amateur of horticulture, will readily remember the rustic prospect-arbor, or tower. . . which was situated at the extremity of this place. It was one of the first pieces of rustic work of any size, and displaying any ingenuity, that we remember to have seen here; and from its summit, though the garden walks afforded no prospect, a beautiful reach of the neighborhood for many miles was enjoyed.” [Fig. 9]

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1849, describing the estate of William H. Aspinwall, Staten Island, NY (1849; repr., 1991: 52)[8]

- “The Cottage residence. . . is a highly picturesque specimen of Landscape Gardening. . . In improving this picturesque site, a nice sense of the charm of natural expression has been evinced; and the sudden variations from smooth open surface, to wild wooden banks, with rocky, moss-covered flights of steps, strike the stranger equally with surprise and delight. A charming greenhouse, a knotted flower-garden, and a pretty, rustic moss-house, are among the interesting points of this spirited place.”

- Kirkbride, Thomas S., 1844, describing the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane (1851: 24–25)[9]

- “IMPROVEMENT OF THE PLEASURE GROUNDS. – During the year just closed, the prosecution of contemplated improvements upon the forty-one acres which compose our pleasure grounds, and are within the enclosure, has also furnished a great variety of interesting employment to various classes of patients. Many trees and shrubs have been planted; flower borders have been enlarged and improved; the brick walks, for use when the ground is soft or covered with snow, have been extended; other walks have been laid out through the different groves, and covered with tan, and their extension, now in progress, will give us more than a mile in the men’s division, and nearly as much in that appropriated to the females. These walks have been so located as to embrace our finest and most diversified views, to wind through the woods and clumps of trees which are scattered through the enclosure; and among them, it is hoped, will soon be seen summer-houses, rustic seats, and other objects of interest, to tempt the patients voluntarily to prolong their walks, and to spend a greater portion of their time out of the wards, and engaged in some agreeable occupation.

- “The importance and utility of having the grounds about an insane hospital highly cultivated and improved, and everything in perfect order, is much greater than is generally supposed. It exercises a beneficial influence on all patients and on their friends. The good taste of many enables them to appreciate all such things in detail, many are pleased with them as a whole and even those who are not capable of realizing their beauties, still have an indistinct recollection of something pleasant in connexion with them. . .

- “A surprising degree of interest is frequently excited among the patients, by having everything done in the neatest and best manner, by having fixtures and apparatus of the most approved kinds, and all the buildings and arrangements showing a peculiar fitness for the purposes for which they are intended. It is where these principles are fully carried out, that a farm, a garden, and various other external matters, become truly valuable aids in the management of the insane.”

Citations

- Gibbs, James, 1728, A Book of Architecture (1728: xix, xxi)[10]

- “Two Uprights of another Pavillion built at Hackwood. The Rustick Front looks upon a fine piece of Water, and the other on a beautiful Parterre. . . .

- “Three Designs for Columns, proper for pub-lick Places or private Gardens; viz. a plain Dorick Column upon its Pedestal with a Vase a top, a fluted Column properly adorn’d, and a Rustick frosted Column, with a Figure a-top, as I have made them for several Gentlemen. The Proportions of them are mark’d upon an upright Line, divided into so many Diameters of the Column for the Height.”

- Gregory, G. (George), 1816, A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (1816: 2:n.p.)[11]

- “GARDENING. . .

- “Near some pieces of water, as a cool retreat, it is desirable that there should be something of the summer-house kind; and why not the simple rustic arbour, embowered with the woodbine, the sweetbriar, the jessamine, and the rose? Pole arbours are tied well together with burk or ozier twigs.”

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826: 792)[12]

- “6092. Rustic fences formed of shoots of the oak, hazel, or larch, may often be introduced with good effect both as interior and surrounding barriers.”

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828: 2:n.p.)[13]

- “RUST’IC, RUST’ICAL, a. [L. rusticus, from rus, the country.]

- “1. Pertaining to the country; rural; as the rustic gods of antiquity. Encyc.

- “2. Rude; unpolished; rough; awkward; as rustic manners or behavior.

- “3. Coarse; plain; simple; as rustic entertainment; rustic dress.

- “4. Simple; artless; unadorned. Pope.

- “Rustic work, in a building, is when the stones, &c. in the face of it, are hacked or pecked so as to be rough. Encyc. . .

- “RUSTIC, n. An inhabitant of the country; a clown.”

- Sayers, Edward, 1838, The American Flower Garden Companion (1838: 131–32)[14]

- “. . . the margin of the pond should be planted with drooping willows and trees of a pendulous habit for shade, under which a rustic seat might be properly placed for the accommodation of those who desire to view the sporting fishes, and other interesting objects by which they are surrounded. . .

- “In some convenient place near the rockery, a rustic arbor may be very properly placed, and covered with native vines and creepers, for the accommodation of visitors, and the junior members of the family who wish to study botany.”

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1838, The Suburban Gardener (1838: 160–61, 166–69, 467)[5]

- “What is called the English, or natural, style of gardening, however, may be divided into three kinds: the picturesque, the gardenesque, and the rustic. . . the rustic style [has a constant reference] to what is commonly found accompanying the rudest description of labourers’ cottages in the country. The object of this last-mentioned style, or rather manner, is also to produce such fac-simile imitations of common nature, as to deceive the spectator into an idea that they are real or fortuitous. . .

- “The Rustic, Indigenous, or Fac-simile Imitations of Natural Scenery. . . Such scenes differ from those of the geometric style, and also from those of artistical imitation, in this, that the same person who contrives them must also execute them. They can have no merit in design, and only mechanical merit in the execution. They scarcely require the aid of either a professional landscape-gardener, or a professional horticulturist; but, at the same time, they could not be executed by every common labourer. The imitation of such scenes must be made by a sort of self-taught artist, or a regularly instructed artist who will condescend to accept of this kind of employment.

- “there are often clay pits or gravel pits on the ground which is to be let for building on; as in other situations there are old chalk pits or stone quarries. . . As a first example, we shall suppose that the pit is a clay pit, and not fit for a human habitation at the bottom. In this case, let the bottom of the pit be covered with turf, smooth in some places, and in others mixed with nettles, thistles, and other weeds, and varied by thorns, briars, brambles, elder bushes, and other trees and shrubs that generally spring up on waste ground. In one or two parts of the bottom of the pit let there be pools of water, with rushes and other aquatic plants, and some alders and willows of the commonest kind for shade. These and other details being executed in the bottom of the pit, surround it on the outside by a thick plantation of one or two kinds of trees and shrubs, such as are generally found in copse-wood; and let there be a winding straggling path through this copse-wood, of such a length as to obliterate for the moment the impression of the artificial scenery of the other parts of the pleasure-grounds on the mind of the spectator while he is pursuing the winding slightly marked path among the bushes to the bottom of the pit. If the plantation were surrounded by a hedge or other fence, and the entrance to the path were through a gap in this fence, the deception would be the more complete.

- “The second example we shall suppose to be a dry gravel pit, and that in the bottom of it a dwelling-place might be formed for a workman and his wife, with a hovel to serve as a cow-shed, in which cows might be kept for the family, and in which also an ass might be kept for the use of the gardener, in rolling his walks, carting manure and weeds, and for other purposes. Instead of a crooked footpath entering through a gap in a hedge, as in the first example, a rough winding road might be formed, by which it might be supposed that the gravel had been carted out of the pit, but which, owing to the lapse of time, had become principally covered with grass; and this might be entered through an old rickety gate; while in the bottom of the pit there might be the cottage dwelling, and the hovels, which, though comfortable within, ought to appear in a half-ruined state without; and a hayrick rudely fenced round, with a small stack of fagots for fuel, &c. The reader can easily supply the rest.

- “Both these examples would be fac-simile imitations, which might easily be mistaken for nature itself, or what we call rustic scenery; and though they might, and doubtless would, afford pleasure in themselves, and as contrasted with the scenery around them, yet that pleasure could in no respect be considered as resulting from them as works of art, unless we were told that they were artificial creations. . .

- “With respect to those modifications of the irregular style which we have described as the picturesque, gardenesque, and rustic or rural, the first, as it requires least labour in the management, is best adapted for grounds of considerable extent; the second is more suitable for those persons who are botanists rather than general admirers of scenery, because it is best calculated for displaying the individual beauty of trees and plants, and the high order and keeping of lawns, walks, &c.; and the third for persons of a romantic or sentimental turn of mind, who delight in surrounding themselves with scenery associated with a station in life strongly opposed to that in which they are really placed; or to attract attention by producing a striking contrast to refined and artistical scenery, whether in the irregular or geometric styles. . . .

- “Fig. 173. is another design for a rustic seat of the same general character, but on a smaller scale, and more elaborately finished. The lower part of the bonnet roof, instead of being of thatch, is of strips of wood with the bark on, closely joined, so as to exclude rain. The seat is also more elaborately finished.” [Fig. 10]

- Rusticus [pseud.], August 1846, “Design for a Rustic Gate” (Horticulturist 1: 72)[15]

- “Indeed, rustic work of all kinds is extremely pleasing in any situation where there is any thing like a wild or natural character; or even where there is a simple and rustic character. In the immediate proximity of a highly finished villa, it strikes me that rustic work, such as arbors, fences, flower baskets and the like, are rather out of place. The sculptured vase of marble, or terra cotta, would appear to be the most in keeping with an elegant place of the first class; that is to say, for all situations very near the house. In wooded walks, or secluded spots, rustic work looks well always.”

- Johnson, George William, 1847, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening (1847: 525)[16]

- “RUSTIC STRUCTURES are pleasing in recluse portions of the pleasure ground, if this style to be confined to the formation of either a seat, or a cottage; but it is ridiculous and disgusting to good taste, if complicated and elegant forms are constructed of rude materials. Thus we have seen a flower-box, intended to be Etruscan in its outlines, formed of split hazel stakes—a combination of the rude and the refined, giving rise to separate trains of ideas totally unassociable.”

- Webster, Noah, 1848, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1848: 972)[17]

- “RUS’TIC, RUS’TIC-AL, a. [L. rusticus, from rus, the country.] . . .

- “5. In architecture, a term denoting a species of masonry, the joints of which are worked with grooves, or channels, to render them conspicuous. The surface of the work is sometimes left or purposely made rough, and sometimes even or smooth. Gloss. of Archit.”

- Elder, Walter, 1849, The Cottage Garden of America (1849: 26–27)[18]

- “If [the rich gentleman’s lawn is constructed] in the rustic style, the beauties of the trees consist in their ivy and mossy trunks, their leaning habits, crooked limbs and other deformities.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1849, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849; repr., 1991: 454–57, 460–61)[8]

- “Open and covered seats are of two distinct kinds; one architectural. . . the other rustic, as they are called, which are formed out of trunks and branches of trees, roots, etc., in their natural forms. . .

- “rustic seats and structures, which, from the nature of the materials employed and the simple manner of their construction, appear but one remove from natural forms, are felt at once to be in unison with the surrounding objects. Again, the mural and highly artistical vase and statue, most properly accompany the beautiful landscape garden; while rustic baskets, or vases, are the most fitting decorations of the Picturesque Landscape Garden. . .

- “We consider rustic seats and structures as likely to be much preferred in the villa and cottage residences of the country. They have the merit of being tasteful and picturesque in their appearance, and are easily constructed by the amateur, at comparatively little or no expense. There is scarcely a prettier or more pleasant object for the termination of a long walk in the pleasure-grounds or park, than a neatly thatched structure of rustic work, with its seat for repose, and a view of the landscape beyond. On finding such an object, we are never tempted to think that there has been a lavish expenditure to serve a trifling purpose, but are gratified to see the exercise of taste and ingenuity, which completely answers the end in view. . .

- “Figure 84 is a covered seat or rustic arbor, with a thatched roof of straw. Twelve posts are set securely in the ground, which make the frame of this structure, the openings between being filled in with branches (about three inches in diameter) of different trees—the more irregular the better, so that the perpendicular surface of the exterior and interior is kept nearly equal. In lieu of thatch, the roof may be first tightly boarded, and then a covering of bark or the slabs of trees with the bark on, overlaid and nailed on. The figure represents the structure as formed round a tree. For the sake of variety this might be omitted, the roof formed of an open lattice work of branches like the sides, and the whole covered by a grape, bignonia, or some other vine or creeper of luxuriant growth. The seats are in the interior. . . [Fig. 11]

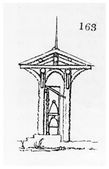

- “Figure 88 is a design for a rustic prospect tower of three stories in height, with a double thatched roof. It is formed of rustic pillars or columns, which are well fixed in the ground, and which are filled in with a fanciful lattice of rustic branches. A spiral staircase winds round the interior of the platform of the second and upper stories, where there are seats under the open thatched roof. . .

- “When the stream is large and bold, a handsome architectural bridge of stone or timber is by far the most suitable; especially if the stream is near the house, or if it is crossed on the Approach road to the mansion; because a character of permanence and solidity is requisite in such cases. But when it is only a winding rivulet or crystal brook, which meanders along beneath the shadow of tufts of clustering foliage of the pleasure-ground or park, a rustic bridge may be brought in with the happiest effect. . . The bark is allowed to remain on in every piece of wood employed in the construction of this little bridge; and when the wood is cut at the proper season (durable kinds being chosen), such a bridge, well made, will remain in excellent order for many years.” [Fig. 12]

- Anonymous, January 1850, “A Few Words on Rustic Arbours” (Horticulturist 4: 320)[19]

- “The most useful and most agreeable of all these [rustic seats], is the simple rustic arbor, with projecting roof, covered with thatch or bark. I send you herewith (see FRONTISPIECE) sketches of two of these, copied from a French volume on garden decorations. I have had one of these executed in a secluded spot, and the effect is highly satisfactory, and a covered arbor like this is agreeable at all seasons of the year, when a walk in the garden is sought after.

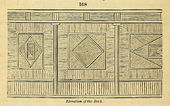

- “Rustic work, made of branches of trees indiscriminately, and exposed to the full action of the weather, perishes very speedily. But if it is protected from the rains by being under the shelter of an overhanging roof, as for example, covered like these arbors, it will last from 10 to 15 years without repairs. But by far the best material, where it can be obtained, is the wood of red cedar, as it will endure for 20 years or more. The stems of young cedars are usually straight, and may be split in halves so as to form excellent pieces for forming the inlaying or panel work of the insides of rustic arbors, as shown in the figures; and the larger limbs will form good pilars and lattice work for the open portions of the exterior. The frame of such arbors as these, is made by setting posts, cedar or other, with the bark on, at the corners, and then nailing rough boards between the posts, in those compartments that are to be worked close. Over these boards the halved or split rods, (those from one to two inches in diameter, are preferable,) are nailed on so as to form any pleasing patterns which the taste or fancy may dictate.” [Fig. 13]

Images

Inscribed

James Gibbs, “Two Uprights of another Pavillion built at Hackwood,” in A Book of Architecture (1728), pl. 73.

J. C. Loudon, Covered seats of the rustic kind, in An Encyclopædia of Gardening, 4th ed. (1826), 357, figs. 334–36.

J. C. Loudon, “Rustic fences,” in An Encyclopædia of Gardening, 4th ed. (1826), 792, fig. 542.

J. C. Loudon, Rough bench in rustic hut decorated in shrubberies, in An Encyclopædia of Gardening, 4th ed. (1826), 809, fig. 561.

J. C. Loudon, Rustic shed for bees, in An Encyclopædia of Gardening, new ed. (1834), 227, fig. 163.

J. C. Loudon, “Rustic arch and vase,” in The Suburban Gardener, and Villa Companion (1838), 581, fig. 231.

J. C. Loudon, “View of the rustic arch,” in The Suburban Gardener, and Villa Companion (1838), 586, fig. 240.

J. C. Loudon, A rustic thatched structure, in The Suburban Gardener, and Villa Companion (1838), 466, fig. 172.

J. C. Loudon, A rustic seat, in The Suburban Gardener, and Villa Companion (1838), 467, fig. 173.

J. C. Loudon, “Entrance to the Flower-garden at Wimbledon House,” in The Suburban Gardener, and Villa Companion (1838), 641, fig. 267. "Rustic structure."

J. C. Loudon, “Rustic Alcove,” Cheshunt Cottage, in The Gardener’s Magazine, and Register of Rural & Domestic Improvement 15, no. 117 (December 1839): 644, fig. 160.

J. C. Loudon, “Covered Seat, of grotesque and rustic Masonry,” Cheshunt Cottage, in The Gardener’s Magazine, and Register of Rural & Domestic Improvement 15, no. 117 (December 1839): 656, fig. 168.

J. C. Loudon, Elevation of the Back Woodwork of a Rustic Covered Seat, Cheshunt Cottage, in The Gardener’s Magazine, and Register of Rural & Domestic Improvement 15, no. 117 (December 1839): 660, fig. 168.

Anonymous, “Rustic Seat,” Montgomery Place, in A. J. Downing, ed., Horticulturist 2, no. 4 (October 1847): 157, fig. 26.

Anonymous, “A Rustic Arbour,” in Louisa Tuthill, History of Architecture (1848), 287, fig. 44.

Anonymous, “Simple rustic seat,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), 456, fig. 82.

Anonymous, “Covered seat or rustic arbor,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), 457, fig. 84.

Anonymous, “Rustic Covered Seat,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), 458, fig. 86.

A. J. Downing, “Design for a rustic prospect tower,” in A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), 460, fig. 88.

Anonymous, “A rustic bridge,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), 461, fig. 89.

Anonymous, “Rustic Arbours,” in A. J. Downing, ed., Horticulturist 4, no. 7 (January 1850): pl. opp. 297.

Associated

Anonymous, Grotto at the garden of Father George Rapp, c. 1820.

Anonymous, “Rustic prospect-arbor,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), 460, fig. 87.

Attributed

Alexander Jackson Davis, Montgomery Place—Shore Seat, n.d.

Alexander Jackson Davis, Rustic Cottage at Blithewood, 1836.

Alexander Jackson Davis, View in Grounds at Blithewood, Seat of Robt. Donaldson, 1840.

Anonymous, “A Rustic Alcove,” in A. J. Downing, ed. Horticulturist 2, no. 8 (February 1848): pl. opp. 345, fig. 4.

Notes

- ↑ Ann Bermingham, Landscape and Ideology: The English Rustic Tradition, 1740–1860 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986), 10, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jeffreys [pseud.], “Critique on November Horticulturist,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 4, no. 7 (January 1850): 311–12, view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. W. S., “Foreign Notices: North America,” Gardener’s Magazine, and Register of Rural & Domestic Improvement 8, no. 36 (February 1832): 70–77, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Hebron Moore, “A View of Philadelphia in 1829: Selections from the Journal of B. L. C. Wailes of Natchez,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 78 (July 1954): 353–60, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, The Suburban Gardener, and Villa Companion (London: Longman et al., 1838), view on Zotero.

- ↑ James Silk Buckingham, The Eastern and Western States of America, 3 vols. (London: Fisher, 1842), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jacquetta M. Haley, ed., Pleasure Grounds: Andrew Jackson Downing and Montgomery Place (Tarrytown, NY: Sleepy Hollow Press, 1988), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America, 4th ed. (1849; repr., Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Story Kirkbride, Reports of the Pennsylvania Hospital for The Insane, with a Sketch of its History, Buildings, and Organization (Philadelphia: Published by order of the Board of Managers, 1851), view on Zotero

- ↑ James Gibbs, A Book of Architecture, Containing Designs of Buildings and Ornaments (London: Printed for W. Innys et al., 1728), view on Zotero.

- ↑ George Gregory, A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences, 1st American ed., 3 vols. (Philadelphia: Isaac Peirce, 1816), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, 4th ed. (London: Longman et al., 1826), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Edward Sayers, The American Flower Garden Companion, Adapted to the Northern States (Boston: Joseph Breck and Company, 1838), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Rusticus [pseud]., “Design for a Rustic Gate,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 1, no. 2 (August 1846): 72–73, view on Zotero.

- ↑ George William Johnson, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening, ed. David Landreth (Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1847), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language. . . Revised and Enlarged by Chauncey A. Goodrich. . . (Springfield, MA: George and Charles Merriam, 1848), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Walter Elder, The Cottage Garden of America (Philadelphia: Moss, 1849), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, “A Few Words on Rustic Arbours,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 4, no. 7 (January 1850): 320–21, view on Zotero.