Pavilion

(Pavillion)

See also: Belvedere, Summerhouse, Temple

History

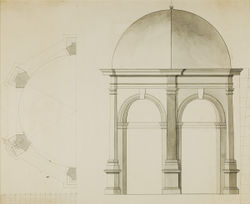

Pavilion was a term that appeared throughout the Eastern colonies and, later, the states from New England to the Deep South. Advertisements for garden services in the 18th and 19th centuries included the pavilion in lists of structures for sale. Ephraim Chambers's 1741—43 definition of a pavilion noted three standard meanings of the term as it was used during the colonial and early Republic periods. First, it referred to a tent-like or domed building under a single roof [Fig. 1]; second, it denoted a projecting piece in front of or on the corner of a building; and third, it described a garden building also known as a summerhouse, temple, or pleasure house. All three denotations have relevance in the history of the designed landscape.

Samuel Johnson's 1755 definition suggested that a pavilion could be a moveable or temporary structure. This type of pavilion was also described in an early 19th-century account of structures built to accommodate socializing and dancing at Custis-Lee Mansion (Arlington House) in Arlington, Virginia. Alexander Jackson Davis in 1836 sketched a canopied pavilion for Blithewood [Fig. 2]. Its delicate appearance suggests that it might have been temporary. Pavilions, however, were more frequently permanent structures that were part of an architectural or landscape design.

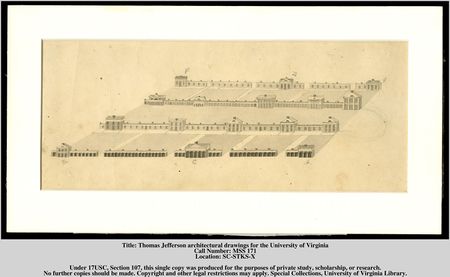

In his design for the University of Virginia, Thomas Jefferson placed along the main lawn two rows of individual professor’s houses, which he identified as pavilions. These temple-like buildings, each ornamented with a different classical order, were linked by covered walkways or piazzas and backed by enclosed gardens. In this instance, the choice of the term with its garden overtones suggests that Jefferson conceived of the whole composition based on the interrelationship of architecture and landscape [Fig. 3]. At Monticello, Jefferson again planned temple-like structures that he called pavilions, which stood at the end of each of two symmetrical walkways that extended from the main house into the garden. A letter of 1808 from Jefferson indicates that he planned to use at least one of these new pavilions as a library.

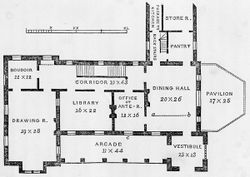

The application of the term “pavilion” to a structure that was attached to a house as a porch-like space seems to have gained popularity with the advent of house pattern books in the 1840s. “More than a veranda,” Downing wrote, the pavilion was “a room in the open air.” For the frontispiece of an issue of the Horticulturist, he used a drawing by Davis depicting the pavilion at Montgomery Place in Dutchess County, New York, through which the surrounding landscape was seen. In another view of the same estate, Davis depicted what was described in the accompanying article as two types of pavilions: an attached structure and a separate temple-like building in the garden [Fig. 4].

The garden pavilion was illustrated in Downing’s publications as a wooden structure made in a variety of light framework types. It had a single roof and generally provided shelter for a garden seat. Some pavilions were simple and rustic in appearance, with climbing plants and curved branches adding to their character, while others offered a more finished treatment, such as circular or pedimental temples designed in the classical style [Fig. 5]. Downing's advocacy of a “unity of expression” and his concern for the appropriateness of style is illustrated by his choice of a pavilion that corresponded in style to the garden and its architectural or topographical features.

Pavilions were often located at the terminus of a walk, the summit of a hill, or the edge of a garden to provide resting and viewing places. The plan for Calverton, near Baltimore [Fig. 6], is an example of a pleasure ground design that uses such criteria to determine the placement of pavilions within the landscape.

The term “pavilion” was often used interchangeably with “summerhouse” and “temple.” A regional preference is not discernable in the textual evidence for any of these terms. Only Noah Webster, in the later edition of An American Dictionary of the English Language (1848), suggested that the word “pavilion” was not appropriate for describing a summerhouse in a garden, without explanation. More commonly, pavilion was used broadly to encompass a variety of garden building types. Within one passage, Downing described one pavilion that formed the north wing of the house at Montgomery Place, and another separate garden temple as a “little rustic pavilion” located at the water’s edge. In either case, the function of the pavilion was to offer an open-air structure with a sheltering roof that was linked visually and spatially with the landscape. Downing (1850) used this particular feature to illustrate the “story of a desideratum growing out of our climate,” and the American adaptation in design to both northern and southern conditions.

—Therese O’Malley

Texts

Usage

- Anonymous, n.d., advertisement for design and construction services for parks and gardens (quoted in Chase 1973: 37–39)[1]

- “[A surveyor by the name of Theophilus Hardenbrook] ‘Designs all sorts of Buildings, well suited to both town and country, Pavilions, Summer-Rooms, Seats for Gardens. . . also Water-houses for Parks. . . Eye Traps to represent a Building terminating a walk, or to hide some disagreeable Object, Rotundas, Colonades, Arcades, Studies in Parks or Gardens, Green Houses for the Preservation of Herbs.’”

- Raspberry, Thomas, 1758, describing yardage of mosquito netting for a pavilion in Savannah, GA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “. . . netted lawn for Pavillions or [M]usqito Netts—10 Yards each ps at 10d per Yd.”

- Carroll, Charles (of Annapolis), 1777, describing Carroll Garden, Annapolis, MD (Maryland Historical Society, A. E. Carroll Papers)

- “I like my pavillions: they are rather small.”

- Bartram, William, 1791, describing Indian village south of Charlotia (1928: 250–51)[2]

- “We were received and entertained friendlily [sic] by the Indians, the chief of the village conducting us to a grand, airy pavilion in the center of the village. It was four square; a range of pillars or posts on each side supporting a canopy composed of Palmetto leaves, woven or thatched together, which shaded a level platform in the center, that was ascended to from each side by two steps or flights, each about twelve inches high, and seven or eight feet in breadth, all covered with carpets or mats, curiously woven, of split canes dyed of various colours. Here being seated or reclining ourselves, after smoaking tobacco, baskets of the choicest fruits were brought and set before us.”

- Latrobe, Benjamin Henry, May 11, 1805, in a letter to Thomas Jefferson, describing the White House, Washington, DC (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “The upper floor of the Middle pavilions, level with the surface of the ground on the North side, and opening on it, must ultimately be destined for coachhouses.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, February 23, 1808, in a letter to Hugh Chisolm, describing Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, VA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “I shall be anxious that the south pavilion be in readiness when I come home in April, because I have as many trunks of books now arrived in Monticello.”

- Caldwell, John Edwards, 1808, describing Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, VA (1951: 38)[3]

- “Through the antes of the house, from N. to S. on the cellar floor, is a passage of 300 feet long, leading to two wings or ranges of building of one story, that stand equi-distant from each end of the house, and extend 120 feet eastwardly from the passages, terminated by a pavillion of two stories at the end of each.”

- Dennie, Joseph, December 1809, describing The Woodlands, seat of William Hamilton, near Philadelphia, PA (The Portfolio 2: 505)

- “The building is of stone, and in the Doric order; the north front is ornamented, in the centre, by six Ionic pilasters, and on each side with a pavilion; the south front by a magnificent portico, twenty-four feet in height, supported by six stately Tuscan columns.”

- Paulding, James Kirke, 1816, describing Berkeley Springs, VA (later WV) (1817: 2:235)[4]

- “There is a pavilion built over the spring, which is used for drinking, and two bath-houses —one for either sex. The spring which supplies the ladies’ bath is one of the finest I have ever seen. It bursts from a fissure in the rock in the form of a cone, much larger than the crown of a hat, and, together with the others, forms a fine stream, in some places six or eight yards wide.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, September 9, 1819, describing Poplar Forest, property of Thomas Jefferson, Bedford County, VA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “I wish you therefore to come with the three carpenters under you, as soon as they have done what I directed, that is to say. . . to put in the sleepers of the north pavilion and secure all the plank and stuff belonging to it.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, June 22, 1822, describing the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “I am suspicious of some mistake in the ornaments for the Pavilion No. 1 which must have happened through looking at the same order in the portico at Monticello that a note tells me of 30 (mettle?) heads but no ox skulls. Should there be any sculls [sic] in the same frieze with human heads. If there ought to I am sorry having cast in (?) 12 human heads for that pavillion 1. In the example by Nicholson from the Baths of Diocletian no ox skull is shown or can I find it so in any other work that I have looked at. In fact this mistake of mine if it is one would extend to every frieze of that order and example, and therefore I see the (validity) of your opinion.”

- Eppes, Francis, June 23, 1826, describing the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “Knowing that all your pavilions at the University have tin coverings, I write to learn whether they have ever leaked, and if so what method or prevention has been used.” [See Fig. 3]

- Smith, Margaret Bayard, August 2, 1828, describing the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (1906: 225–56)[5]

- “. . . on two other sides running from north to south are the Pavillions, or Professor’s houses, at about 60 or 70 feet apart, connected by terraces, beneath which are the dormitories, or lodging sleeping rooms of the students. The terrace projects about 8 feet beyond the rooms and is supported on brick arches, forming beneath the arches a paved walk, sheltered from the heat of summer and the storms of winter. A vast wide lawn separates the two rows of pavillions and dormitories. . . There are 12 Pavillions, each one exhibiting the different orders of architecture and built after classic models, generally Grecian.”

- Thacher, James, December 3, 1830, “An Excursion on the Hudson,” describing Hyde Park, seat of David Hosack, on the Hudson River, NY (New England Farmer 9: 156)[6]

- “At the termination of these romantic walks fanciful pavilions are erected, where visitors may contemplate a captivating display of nature’s magnificence in these regions of wonder.”

- Martineau, Harriet, 1834, describing Hyde Park, seat of David Hosack, on the Hudson River, NY (1838: 1:55)[7]

- “Then crossing the road, after paying our respects to his dairy of fine cows, we drove through the orchard, and round Cape Horn, and refreshed ourselves with the sweet river views on our way home. There we sat in the pavilion, and he told me much of De Witt Clinton, and showed me his own Life of Clinton, a copy of which he said should await me on my return to New-York.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, October 1847, describing Montgomery Place, country home of Mrs. Edward (Louise) Livingston, Dutchess County, NY (quoted in Haley 1988: 46, 47, 52)[8]

- “Without going into any details of the interior, we may call attention to the unique effect of the pavilion, thirty feet wide, which forms the north wing of this house. It opens from the library and drawing-room by low windows. Its ribbed roof is supported by a tasteful series of columns and arches, in the style of an Italian arcade. As it is on the north side of the dwelling, its position is always cool in summer; and this coolness is still farther increased by the abundant shade of tall old trees, whose heads cast a pleasant gloom, while their tall trunks allow the eye to feast on the rich landscape spread around it. [Fig. 7]

- “At the distance of some hundred yards, we find ourselves on the river shore, and on a pretty jutting point of land stands a little rustic pavilion, from which a much lower and wider view of the landscape is again enjoyed. . .

- “Passing under neat and tasteful archways of wirework, covered with rare climbers, we enter what is properly

- “THE FLOWER GARDEN.

- “In the centre of the garden stands a large vase of the Warwick pattern; others occupy the centres of parterres in the midst of its two main divisions, and at either end is a fanciful light summer-house, or pavilion, of Moresque character.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1850, describing a design for a country house (1850: 357)[9]

- “[Referring to Design XXXII] On the right of this hall is a noble veranda, which, for want of a better name, we call the pavilion. To a Southern house, this would be the greatest necessity, besides adding much to the architectural beauty of the house—for, in fact, such a pavilion would be the lounging place, conversazione, and often dining-room itself, since it would be the coolest, airiest, and most agreeable part of the house during a certain part of the day. In summer, this pavilion, or its shadow, would give a softened light to the dining hall, while the large windows, thrown open to the floor, between the two, would make the dining-room fresh and pleasant in the most sultry days. To vary the uses of the pavilion, we will only suggest that the dinner being over, the dessert might be served there, and the dessert being concluded, gentlemen addicted to the soothing indulgence of a fragrant ‘Havana,’ would find the pavilion the best of smoking apartments, after the ladies had retired to the drawing-room.

- “Even in the Middle states, the enjoyment of a large pavilion of this kind is very great during four months of the year. The only example that we have seen of such an appendage to the house is at Montgomery Place—one of the finest seat on the Hudson, where it is placed on the drawing-room side of the house, and at once impresses every visitor by its combination of beauty, dignity and utility. In short, although this feature may be omitted, without materially diminishing the beauty or convenience of this design, its adoption would give a completeness and significance to a first-rate country-house like this; completeness, since it affords something more than a veranda, viz. a room in the open air, the greatest luxury in a warm summer; significance, since it tells the story of a desideratum growing out of our climate, architecturally and fittingly supplied.” [Fig. 8]

- Vedder, Sarah E., 1830–51, describing Custis-Lee Mansion (Arlington House), Arlington, VA (Junior League of Washington 1977: 77)[10]

- “Arlington. . . was daily visited by strangers, and many were the picnic parties enjoyed there in the lovely woods surrounding the mansion. . . Mr. Custis had two or three pavillions built to accommodate the parties, either to set the tables or to dance. Frequently he would come down to the grounds and participate in their amusements.”

Citations

- Dezallier d’Argenville, Antoine-Joseph, 1712, The Theory and Practice of Gardening (1712: 76–77)[11]

- “The Ends and Extremities of a Park are beautified with Pavilions of Masonry, which the French call Belvederes, or Pavilions of Aurora, which are as pleasant to rest ones self in, after a long Walk, as they are to the Eye, for the handsome Prospect they yield; they serve also to retire into for Shelter when it rains. The word Belvedere is Italian, and signifies a beauteous Prospect, which is properly given to these Pavilions.”

- Chambers, Ephraim, 1743, Cyclopaedia (1743: 2:n.p.)[12]

- “PAVILLION,*in architecture, signifies a kind of turret, or building usually insulated, and contained under a single roof; sometimes square, and sometimes in form of a dome: thus called from the resemblance of its roof to a tent.

- “*The word comes from the Italian padiglione, tent, and that from the Latin papilio.

- “Pavillions are sometimes also projecting pieces, in the front of a building, marking the middle thereof. . .

- “There are pavillions built in gardens, popularly called summer-houses, pleasure-houses, &c.—Some castles or forts consist only of a single pavillion.”

- Johnson, Samuel, 1755, A Dictionary of the English Language (1755: 2:n.p.)[13]

- “PAVI’LION. n.s. [pavillion, French.] A tent; a temporary or moveable house.”

- Repton, Humphry, 1803, Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1803: 153)[14]

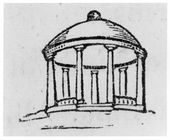

- “Yet the summit of a naked brow, commanding views in every direction, may require a covered seat or pavilion; for such a situation, where an architectural building is proper, a circular temple with a dome, such as the temple of the Sybils, or that of Tivoli, is best calculated.”

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828: 2:n.p.)[15]

- “PAVILION, n. pavil’yun [Fr. pavillon; Sp. pabellon; Port. pavilham; Arm. pavihon; W. pabell; It. paviglione and padiglione; L. papilio; a butterfly, and a pavilion. According to Owen, the Welsh pabell signifies a moving habitation.]

- “1. A tent; a temporary movable habitation.

- “2. In architecture, a kind of turret or building, usually insulated and contained under a single roof; sometimes square and sometimes in the form of a dome. Sometimes a pavilion is a projecting part in the front of a building; sometimes it flanks a corner. Encyc.”

- Webster, Noah, 1848, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1848: 806)[16]

- “1. A tent. . .

- “2. In architecture, a kind of turret. . . Gwilt.

- “The name is sometimes, though improperly, given to a summer-house in a garden. Brande.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1849, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849; repr. 1991: 456, 473)[17]

- “The temple and the pavilion are highly finished forms of covered seats, which are occasionally introduced in splendid places, where classic architecture prevails. There is a circular pavilion of this kind at the termination of one of the walks at Mr. Langdon’s residence, Hyde Park. . . [Fig. 9]

- “Unity of expression is the maxim and guide in this department of the art, as in every other. . .

- “With regard to pavilions, summer-houses, rustic seats, and garden edifices of like character, they should, if possible, in all cases be introduced where they are manifestly appropriate or in harmony with the scene. Thus. . . a classic temple or pavilion may crown a beautiful and prominent knoll.”

Images

Inscribed

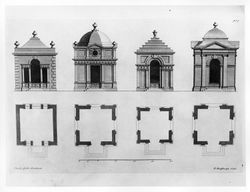

James Gibbs, “Two other Pavilions propos’d for the same place [Bowling-Green at Down Hall in Essex],” in A Book of Architecture (1728), pl. 69.

James Gibbs, “A Pavilion design’d for Sir John Curzon for his seat near Derby,” in A Book of Architecture (1728), pl. 70.

James Gibbs, “Two Uprights of another Pavillion built at Hackwood,” in A Book of Architecture (1728), pl. 73.

James Gibbs, “The Plan, Upright and Section of a Pavillion [sic] for the Right Honorable the Lord Viscount Cobham in his Garden at Stowe in Buckinghamshire,” in A Book of Architecture (1728), pl. 75.

James Gibbs, “Another Design for two Pavillions at Stowe,” in A Book of Architecture (1728), pl. 76.

James Gibbs, Four of “Eight Square Pavillions for my Lord Cobham and others,” in A Book of Architecture (1728), pl. 77.

Thomas Jefferson, Plan of Monticello with oval and round flower beds [detail], 1807.

Thomas Jefferson, Early study for pavilion VII, University of Virginia, 1817.

Anonymous, “Plan of a Mansion Residence, laid out in the natural style,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), 115, fig. 25. “A prospect tower, or rustic pavilion, on a little eminence overlooking the whole estate is shown at j.”

Anonymous, “Principal Floor” of a Southern Villa—Romanesque Style, in A. J. Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850), 353, fig. 169.

Associated

William Bartram, Plan of a “plantation” (or “villa”) of a Creek Indian chief, in “Observations on the Creek and Cherokee Indians” (1789), from Transactions of the American Ethnological Society 3, part 1 (1853): 38, fig. 1.

William Bartram, Plan of a Cherokee Private “Habitation,” in “Observations on the Creek and Cherokee Indians” (1789), from Transactions of the American Ethnological Society 3, part 1 (1853): 56, fig. 5.

Joshua Rowley Watson, From the Piazza looking towards the Pavilion 21st May 1817, 1817.

Thomas Jefferson, Bird’s-eye view of the University of Virginia, c. 1820. This view depicts the 16 campus pavilions, which were positioned at intervals on the lawn and back gardens.

Jane Braddick Peticolas, View of the West Front of Monticello and Garden, 1825. Jefferson’s pavilions frame this depiction of the main house.

Alexander Jackson Davis, Canopied pavilion at Blithewood, 1836.[18]

Alexander Jackson Davis, Montgomery Place—Shore Seat, c. 1847.

Alexander Jackson Davis, “Montgomery Place,” in A. J. Downing, ed., Horticulturist 2, no. 4 (October 1847): pl. opp. 153.

Alexander Jackson Davis, View from Montgomery Place, October 1847.

Anonymous, “A Rustic Alcove,” in A. J. Downing, ed. Horticulturist 2, no. 8 (February 1848): pl. opp. 345, fig. 4.

Anonymous, “View in the Grounds at Hyde Park,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), pl. opp. 45, fig. 1.

Anonymous, “A circular pavilion,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), 456, fig. 81.

Attributed

Thomas Jefferson, Design for a decorative outchamber at Monticello, c. 1778.

Pierre Pharoux, Frontal view of two pavilions on the water for the city of Speranza, 1795.

Pierre Pharoux, Aerial view of two pavilions on the water for the city of Speranza, 1795.

William Russell Birch, “Fountain Green Pennsylv.a the Seat of Mrs. Meeker,” The Country Seats of the United States (1808), pl. 8.

Thomas Kelah Wharton, Crystal Cove, Hyde Park. New York, September 11, 1839.

Alexander Jackson Davis, Octagonal Garden Structure for Montgomery Place, c. 1850

Notes

- ↑ David B. Chase, “The Beginnings of the Landscape Tradition in America,” Historic Preservation 25 (1973): 34–41, view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Bartram, Travels through North and South Carolina, Georgia, East and West Florida, ed. Mark Van Doren (New York: Dover, 1928), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Edwards Caldwell, A Tour through Part of Virginia, in the Summer of 1808; Also, Some Account of the Islands of the Azores, ed. William M. E. Rachal (Richmond, VA: Dietz, 1951), view on Zotero.

- ↑ James Kirke Paulding, Letters from the South, 2 vols. (New York: James Eastburn, 1817), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Margaret Bayard Smith, The First Forty Years of Washington Society, ed. Gaillard Hunt (New York: Charles Scribner’s, 1906), view on Zotero.

- ↑ James Thacher, “An Excursion on the Hudson. Letter II,” New England Farmer, and Horticultural Journal 9, no. 20 (December 3, 1830): 156–57, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Harriet Martineau, Retrospect of Western Travel, 2 vols. (London: Saunders and Otley, 1838), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jacquetta M. Haley, ed., Pleasure Grounds: Andrew Jackson Downing and Montgomery Place (Tarrytown, NY: Sleepy Hollow Press, 1988), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, Landscape Gardening and Rural Architecture (New York and London: Wiley and Putnam, 1850), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Junior League of Washington, The City of Washington: An Illustrated History (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1977), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A.-J. (Antoine Joseph) Dézallier d’Argenville, The Theory and Practice of Gardening; Wherein Is Fully Handled All That Relates to Fine Gardens, . . . Containing Divers Plans, and General Dispositions of Gardens, trans. John James (London: Geo. James, 1712), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Ephraim Chambers, Cyclopaedia, or An Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences . . . , 5th ed., 2 vols. (London: D. Midwinter et al., 1741–43), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language: In Which the Words Are Deduced from the Originals and Illustrated in the Different Significations by Examples from the Best Writers, 2 vols. (London: W. Strahan for J. and P. Knapton, 1755), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Humphry Repton, Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (London: Printed by T. Bensley for J. Taylor, 1803), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language. . . Revised and Enlarged by Chauncey A. Goodrich (Springfield, MA: George and Charles Merriam, 1848), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America, 4th ed. (1849; repr., Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alexander Jackson Davis, Blithewood Estate, Barrytown, N.Y., 1830-1870, view on Zotero.