Belvedere/Prospect tower/Observatory

(Belvidere, Prospect-arbour, Prospect gallery)

See also: Pavilion

History

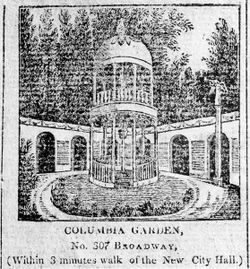

The feature known as belvedere, prospect tower, or observatory was a raised structure or tower placed either on top of a building or as an independent structure in the garden. The belvedere provided a viewing platform from which to look out to the garden or surrounding landscape. With a continuous tradition in Europe since the Renaissance, by the late 18th century the belvedere was recorded as being part of American gardens. Although many images have been collected illustrating this feature in American gardens, relatively few specific written references have been found. It seems that the terms “tower,” “pavilion,” “summerhouse,” “obelisk,” and “column” were all used interchangeably to describe multi-storied structures that permitted viewers to ascend to a height that would offer a new, broader view not available from ground level [Fig. 1]. Regarding André Parmentier’s Horticultural and Botanical Garden in Brooklyn, New York, A. J. Downing (1849) reported that although “the garden walks afforded no prospect,” from the summit of the tower, “a beautiful reach of neighborhood for miles was enjoyed.” In 1802 Eliza Southgate described the summerhouse at the Elias Hasket Derby Farm, which had a staircase “by which you ascend into a square room. . . it has a fine airy appearance and commands a view of the whole garden.”[1]

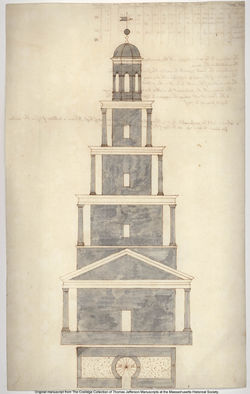

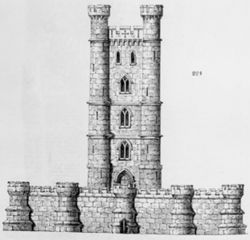

The belvedere in the garden was often the focus of highly inventive designs, such as the observation tower at Monticello. During the course of several years, Jefferson made alternate designs for a multi-staged tower [Figs. 2 and 3], in which he experimented with a Gibbsian round-headed cupola for one and for the other a castellated turret. This latter design represents an early American foray into the Gothic revival style that would become popular only after the turn of the century, as seen in a British example that J. C. Loudon had published in An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1834) [Fig. 4]. Notes on the verso of Jefferson’s c. 1771 drawing indicate that the tower was intended for “directing the line of sight to Monticello.” He later changed his mind and planned a 200-foot tall column, with a balustrade at the top.[2]

Belvedere or prospect towers were designed in all shapes and sizes. The central characteristic of the feature was that it provided a viewing platform rising above the surrounding site, offering a beautiful view, a prospect, a bel vedere. The importance of the prospect is critical to understanding the belvedere in landscape design. Since ancient Rome, the awareness of the delights of the prospect guided the development of villa design.[3] The drawing of the belvedere in the grounds of the Vassall-Craigie-Longfellow House [Fig. 5] gives some sense of the concern for height; it is depicted as located on top of a hill with angles of sight measured from its peak to the lowest ground level. The image of the tower at Monte Video [Fig. 6] illustrates that the height of the belvedere contributed to its importance in the designed landscape.

The provision of height for a belvedere could be achieved either by building a multi-staged tower, as at Monticello and the Vassall-Craigie-Longfellow House, or by placing a viewing platform on top of another building or by using the natural eminence of a hilltop, cliff, or water’s edge. A painting of Harlem in Baltimore [Fig. 7] depicts both a prospect tower and a castellated belvedere surmounting the mansion itself. The Harlem tower, in fact, looks like a raised summerhouse. It was reported to be “a pavilion,” on an eminence under which was “a well-constructed ice vault.”[4]

The stylistic ornamentation and even basic shape of these constructions ranged broadly. A. J. Downing (1849) for example, as a proponent of rural architecture, recommended that prospect towers be constructed of rustic branches and thatch such as that at André Parmentier’s Horticultural and Botanical Garden in Brooklyn, New York. The observatory at Bute, Massachusetts, described by William Bailey Lang (1845), adhered more closely to the neoclassical tradition, and resembled a truncated obelisk, another popular form of belvedere. Observation towers in the form of monumental obelisks were frequently used for public monuments, beginning with Solomon Willard’s design of 1825 for the Bunker Hill Monument in Boston.[5]

The garden belvedere was carefully sited so as to take in the most desirable views of the property and the landscape surrounding it. For example, the location of the belvedere at Point Breeze in Bordentown, New Jersey, facilitated a view that encompassed both the natural and designed landscapes surrounding the mansion. A painting of Cannon House and Wharf depicts a prospect tower in the garden [Fig. 8]. This house belonged to the family of Capt. John Cannon, a prominent merchant in New York; the belvedere would have provided a fine view of the wharf and harbor that was the source of the family’s wealth and fame. A. J. Downing described an “American Mansion” with a plan that included a prospect tower “on a little eminence overlooking the whole estate,” suggesting again, the claim of ownership implied by the view.[6]

“Belvedere” or related words were often given as names to country seats in America. Estates called “Belvidere” could be found in the cities of Richmond and Baltimore and the state of New York, to mention just a few examples. It carried with it a sense of pride of ownership and the importance of selecting a site with a bel vedere (see Alcove, Eminence, Prospect, and View for further discussion of the significance and control of vision in American gardens).[7]

—Therese O'Malley

Texts

Usage

- Anburey, Thomas, September 2, 1781, describing the Moravian community in Bethlehem, PA (1781; repr., 1969: 2:513)[8]

- “The house of the single men is upon the same principle as that of the women; upon the roof of which is a Belvidere, from whence you have not only a most delightful prospect, but a distinct view of the whole settlement.”

- Wansey, Henry, May 17, 1794, describing New York, NY (1970: 76)[9]

- “In the evening. . . took a walk. . . to the Belvidere, about two miles out of New York towards the Sound, an elegant tea drinking house, encircled with a gallery, at one story high, where company can walk round the building and enjoy the fine prospect of New York harbour and shipping. You have a delightful sea view from thence, commanding Staten, Long Island and Governor’s Island, Paulus Hook, Brooklyn and the Sound.”

- Lang, William Bailey, 1845, describing the observatory at Butte, MA (1845: n.p.)[10]

- “OBSERVATORY AT BUTE.

- “FEW persons are aware of the advantages to be gained in prospect by a slight elevation upon their grounds. This Observatory, situated in the woods of BUTE, is only thirty feet high, yet from its top may be seen Boston, Cambridge, Charlestown, Chelsea, Dorchester, the Ocean, and the Hotel at Nahaut.” [Fig. 9]

- Tuthill, Louisa C. (Louisa Caroline), 1848, describing the country seat of Gerard Halleck, New Haven, CT (1848; repr., 1988: 284)[11]

- “An Elizabethan villa, the country-seat of Gerard Halleck, Esq. It stands by the water-side, near the shore of New Haven harbour. The observatory commands an extensive and beautiful prospect.”

Citations

- Dezallier d’Argenville, Antoine-Joseph, 1712, The Theory and Practice of Gardening (1712: 76–77)[12]

- “THE Ends and Extremities of a Park are beautified with Pavilions of Masonry, which the French call Belvederes or Pavilions of Aurora, which are as pleasant to rest ones self in, after a long Walk, as they are to the Eye, for the handsome Prospect they yield; they serve also to retire into for Shelter when it rains. The Word Belvedere is Italian, and signifies a beauteous Prospect, which is properly given to these Pavilions.”

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828: n.p.)[13]

- “BEL’VIDERE, n. [L. bellus, fine, and video, to see.] . . .

- “2. In Italian architecture, a pavilion on the top of an edifice; an artificial eminence in a garden. Encyc.”

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1834, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1834: 616)[14]

- “2619. The prospect-tower is a noble object to look at, and a gratifying and instructive position to look from. It should be placed on the highest grounds of a residence, in order to command as wide a prospect as possible, to serve as a fixed recognised point to strangers in making a tour of the grounds. It may very properly be accompanied by a cottage; or the lower part of it may be occupied by the family of a forester, gamekeeper, or any rural pensioner, to keep it in order, &c.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1849, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849; repr., 1991: 116–17, 459–60)[15]

- “A prospect tower is a most desirable and pleasant structure in certain residences. Where the view is comparatively limited from the grounds, on account of their surface being level, or nearly so, it often happens that the spectator, by being raised some twenty-five or thirty feet above the surface, finds himself in a totally different position, whence a charming coup d’oeil or bird’s-eye view of the surrounding country is obtained. Those of our readers who may have visited the delightful garden and grounds of M. Parmentier, near Brooklyn, some half a dozen years since. . . will readily remember the rustic prospect-arbor or tower, Fig. 87, which was situated at the extremity of his place. . . from its summit, though the garden walks afforded no prospect, a beautiful reach of neighborhood for many miles was enjoyed. Figure 88 is a design for a rustic prospect tower of three stories in height, with a double thatched roof. It is formed of rustic pillars or columns, which are well fixed in the ground, and which are filled in with a fanciful lattice of rustic branches. A spiral staircase winds round the interior of the platform of the second and upper stories, where there are seats under the open thatched roof.” [Figs. 10 and 11]

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1850, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850; repr., 1968: 288, 350–51, 360–61)[16]

- “In the second story plan. . . we find four bedrooms of good size, with two small ones, one of them used as a dressing-room. There is also a bath-room, with space for a water-closet at the end of the entry. At a, a narrow flight of stairs ascends to the apartment, 9 by 9 feet, in the top of the tower—which may be a museum or a prospect gallery. . .

- “A smaller and lighter flight of stairs ascends in the tower, from the chamber floor to the top, where there is an apartment, 10 feet square, which may be the private sanctum of the master of the house, or a general belvedere or ‘look-out’ for visitors, as the taste of the proprietor may lead him to appropriate it.” [Fig. 12]

- “This latter apartment, a charming prospect gallery or belvedere in a country of varied scenery, would be a very agreeable feature.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1850, describing a design for a country house (1850: 360-361)[17]

- “In the large dressing room, 13 by 13 feet, there is a light and pretty staircase, rising to the apartment in the upper part of the tower. This latter apartment, a charming prospect gallery or belvedere in a country of varied scenery, would be a very agreeable feature ; hence, the bed-room, 16 by 20, connected with the dressing-room below, might be the "state bed-room," with both dressing-room and belvedere attached to it.” [Fig. 13]

Images

Inscribed

George Hayward after J. Anderson, View of The Belvedere Club House 1794, 1828.

J. C. Loudon, “A lofty prospect tower,” in An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1834), 328, fig. 224.

Miller & Co., Map of the residence & park grounds, near Bordentown, New Jersey: of the late Joseph Napoleon Bonaparte, ex-king of Spain, 1847.

Anonymous, “Plan of a Mansion Residence, laid out in the natural style,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849), 115, fig. 25.

A. J. Downing, “Design for a rustic prospect tower,” in A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849), 460, fig. 88.

Associated

Anonymous, Map of Mr. Parmentier’s Horticultural and Botanical Garden, at Brooklyn, Long Island, Two Miles From the City of New York, c. 1828. A prospect is indicated by the letter "I" in the upper left hand corner of the garden (rustic arbor).

Anonymous, “Second Floor” of a Villa in the Italian Style, in A. J. Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850), 288, fig. 121.

Anonymous, “A Lake or River Villa,” in A. J. Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850), pl. opp. 343, fig. 164.

Anonymous, "Southern Villa—Romanesque Style," in A. J. Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850), pl. opp. 353, fig. 168.

Anonymous, “Second Floor” of A Villa in the Romanesque Style, in A. J. Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850), 361, fig. 170.

Anonymous, “Rustic prospect-arbor,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849), 460, fig. 87.

Attributed

Thomas Jefferson, Study for an observation tower for Monticello, c. 1771.

Thomas Jefferson, Study for an observation tower for Monticello, c. 1784.

Jonathan Budington, View of the Cannon House and Wharf, 1792. The belvedere is seen in the distant center, left of the house.

Charles Saunders, The survey of a tract of Land in Cambridge. And a perspective delineation of the Summer house theron, Mathematical Thesis, 1802.

William S. Jewett, Mount Washington, 1847.

Samuel McIntire, Elevation of the summer house designed for the Elias Hasket Derby Farm, n.d.

Notes

- ↑ Fiske Kimball, Mr. Samuel McIntire, Carver, the Architect of Salem (Portland, ME: Southworth-Anthoensen, 1940), 75–76, view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Howard Adams, ed., The Eye of Thomas Jefferson (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1976), 332 and 336, view on Zotero. William L. Beiswanger, “The Temple in the Garden: Thomas Jefferson’s Vision of the Monticello Landscape,” in Eighteenth Century Life 8 (January 1983): 175–76, view on Zotero.

- ↑ James S. Ackerman, The Villa: Form and Ideology of Country Houses (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990), 61, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Federal Gazette, 14 June 1800, as quoted in Barbara Wells Sarudy, “Eighteenth-Century Gardens of the Chesapeake,” Journal of Garden History 9, no. 3 (July 1989): 136, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Zukowsky, “Monumental American Obelisks: Centennial Vistas,” Art Bulletin 58 (December 1976): 578, view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1991), 116, view on Zotero.

- ↑ For a case study on this issue of creating views and prospects see Elizabeth Kryder-Reid, “The Archaeology of Vision in Eighteenth-Century Chesapeake Gardens,” Journal of Garden History 14, no. 1 (Spring 1994): 42–54, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Anburey, Travels through the Interior Parts of America, 2 vols. (1781; repr., New York: New York Times and Arno Press, 1969), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Henry Wansey, Henry Wansey and His American Journal, ed. David John Jeremy (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1970), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Bailey Lang, Views with Ground Plans, of the Highlands Cottages at Roxbury (Boston: L. H. Bridgham and H. E. Felch, 1845), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Louisa C. Tuthill, History of Architecture, from the Earliest Times; Its Present Condition in Europe and the United States; with a Biography of Eminent Architects, and a Glossary of Architectural Terms, by Mrs. L. C. Tuthill (1848; repr., Philadelphia: Lindsay and Blakiston, 1988), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A.-J. (Antoine Joseph) Dézallier d’Argenville, The Theory and Practice of Gardening; Wherein Is Fully Handled All That Relates to Fine Gardens, . . . Containing Divers Plans, and General Dispositions of Gardens. . . , trans. John James (London: Geo. James, 1712), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, new ed. (London: Longman et al, 1834), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America, 4th ed. (1849; repr. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses; Including Designs for Cottages, Farm-Houses, and Villas (New York: D. Appleton, 1850; repr., New York: Da Capo, 1968), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, Landscape Gardening and Rural Architecture (New York and London: Wiley and Putnam, 1850), view on Zotero.