Point Breeze

Overview

Alternate Names: Bonaparte’s Park

Site Dates: 1816–present

Site Owner(s): Joseph Bonaparte 1816–1844; Joseph Lucien Bonaparte 1844–1847; Thomas Richards 1847–1850; Henry Beckett 1850–1874; Vincentian Fathers of Philadelphia 1874–1911; Harris Hammond 1911; Divine Word Seminary 1941;

Associated People: Theodore Mauroy, master mason; Michel Bouvier, cabinetmaker;

Location: Burlington County, NJ · 40° 9' 19.44" N, 74° 42' 44.89" W

Condition: Altered

Keywords: Alcove; Avenue; Aviary/Bird cage/Birdhouse; Belvedere/Prospect tower/Observatory; Bridge; Drive; Fountain; Lake; Lawn; Park; Parterre; Pavilion; Picturesque; Plantation; Pleasure ground/Pleasure garden; Prospect; Rustic style; Seat; Shrubbery; Statue; Terrace/Slope; View/Vista; Wood/Woods

Point Breeze on the Delaware River was the country estate of Joseph Bonaparte, older brother of Napoleon I, who resided in the United States between 1816 and 1839. Bonaparte regularly welcomed members of the public to enjoy the grounds and river views at Point Breeze, and his landscape design provided an important early model of a picturesque park in the United States.

History

Joseph Bonaparte (1768–1844), the former king of Naples and Spain, known as Count de Survilliers, resided at his country estate, Point Breeze, for much of his time in the United States between 1815 and 1839.[1] He first purchased seven tracts of land comprising approximately 395 acres near Bordentown, New Jersey. A 125-acre farm known as Point Breeze, at the junction of Crosswick Creek and the Delaware River, formed the core of the property. Soon after taking possession of the farm from Stephen Sayre (1736–1818) in July 1816, Bonaparte replaced Sayre’s existing Georgian home with a larger manor house situated on a sixty-foot promontory with spectacular views of the Delaware River.[2] Within four months he amassed an additional three hundred acres, and would continue to add to the estate over the next nineteen years until it reached approximately eighteen hundred acres.[3]

The proximity of Bordentown’s steamboat docks to Point Breeze made the estate readily accessible to visitors. According to Bonaparte, steamboats arrived four times daily (view text). In addition to frequently entertaining dignitaries, including many French exiles, at Point Breeze, Bonaparte welcomed members of the public on a weekly basis to view the picturesque park and gardens, and to see his collection of art (including a version of David’s Napoleon crossing the Alps), decorative arts, and library, then the largest in the United States (view text).[4] Noted artists including Thomas Birch (1779–1851) and Karl Bodmer (1809–1893) created paintings that emphasize Point Breeze’s elevated position over the river and highlight the fruits of Bonaparte’s efforts to transform the landscape, as one nineteenth-century account described it, from “a wild and impoverished tract... into a place of beauty” (view text) [Fig. 1].

For his landscape improvements at Point Breeze, Bonaparte drew on his previous experiences designing gardens at his European estates, Mortefontaine in France (where he lived off and on between 1798 and 1815) and Prangins in Switzerland (where he resided from 1814–1815). His designs reflected the taste for picturesque, asymmetrical landscapes that had recently become popular in France.[5] Point Breeze was an early example of this style of landscape design in the United States.[6] Teams of approximately thirty to fifty workmen planted trees and an orchard, built roads, created a deer park, and made a half-mile-long artificial lake [Fig. 2]. Islands in the lake were planted with velvet grass and exotic trees and shrubs, and swan-shaped pleasure boats were anchored at the boat house with an adjacent garden featuring forget-me-nots and veronica (view text). Twelve miles of carriage roads led passengers around the lake, over stone bridges, and past gazebos.[7] One commentator reported driving by the lake, an aviary, and statues situated in alcoves during a visit to Point Breeze in 1825 (view text).

Bonaparte imported plants and trees from France including apricots and peaches, but he also relied on the services of Philadelphia collectors and nurserymen. In the spring of 1818, for example, Stephen Girard wrote to Bonaparte offering him raspberry bushes, hazelnut trees, and artichokes. In 1821, Bonaparte received from Landreth Nursery shipments of grapevines and assorted shrubs and trees, including “20 White Lindens, 40 Athenia Poplars, 40 Lombardy Poplars, 20 Weeping Willows, [and] 10 Button-Flowering Locusts.” Bonaparte’s park included sassafras and tulip trees, beech, chestnut, ash white birch, sweet gum, dogwood, honey locust, pines, twenty-five species of oak, persimmon trees, and eight species of walnut. According to Bonaparte’s son-in-law, native wildflowers grew in the woods and fountains in the park were surrounded by rustic seats and planted with stargrass, andromeda, and tulip trees. He also reported that Bonaparte had planted azalea, mock orange, viburnum, and rhododendron near the main house.[8] During a visit to Point Breeze in June 1819, the Englishwoman Frances Wright observed that the mansion house stood on a lawn encircled by “the choice shrubs of the American forest, magnolias, kalmias, &c. planted tastefully under the higher trees” (view text).

After a fire destroyed Bonaparte’s first mansion house on January 4, 1820, he reportedly considered buying The Woodlands, William Hamilton’s estate on the west bank of the Schuylkill River, but decided instead to rebuild at Point Breeze. Bonaparte engaged French émigré Michel Bouvier, a skilled cabinetmaker, to supervise the building of the second manor house. It was constructed by expanding the existing stables (view text), which were located further back from the promontory than the first house had been. This new location, as seen in this 1823 sketched plan, provided better protection from high winds that had helped fan the flames and hasten the destruction of the first house. Only a belvedere, with winding interior stairs and various balconies, survived the fire and remained on the promontory [Fig. 3]. This and the terrace nearby offered extensive views of the river (). Bonaparte’s private apartments on the second floor of the home included a balcony, from which he could take in panoramic views of the gardens and river landscape.[9]

In addition to the new mansion, Bonaparte built several other dwellings on the property. The largest of these was a three-story Lake House, erected near the new mansion probably in the spring of 1820. Bonaparte’s daughter Zénaïde (1801–1854) resided in the Lake House with her husband, the ornithologist Charles-Lucien Bonaparte (1803–1857), after they emigrated in 1823.[10] Bonaparte also constructed a smaller guest house, known as the Wash or Ice House; a two-story gardener’s house (still extant) with kitchen garden; and servants’ quarters. The gardener’s house as well as tenant farmhouses were situated on the eastern end of the property, along a main road leading away from the second mansion house. At the site of the original mansion, Bonaparte added the servants’ house and a classical domed-circular temple. Winding sandstone steps led down the steep bluffs from this part of the property to the wharves and docks on Crosswicks Creek below.[11] Bonaparte also constructed subterranean tunnels, modeled after one at his Mortefontaine estate, to connect buildings throughout the grounds. These tunnels facilitated the transportation of supplies and hid laborers as they traversed the property. One tunnel connecting the main manor house to the lake had three doors leading to different destinations in the vicinity: the wine cellar, the Lake House, and icehouses that stored ice cut from the Delaware River in winter.[12]

Bonaparte retained ownership of Point Breeze until his death in 1844, but, finding himself in ill health, he returned permanently to Europe in 1839. After his death, Point Breeze passed to his grandson Joseph Lucien Bonaparte (1824–1865) who sold his grandfather’s possessions and country estate three years later. The purchaser, Thomas Richards (1780–1860) and his wife Anna Bartram (1787–1865), granddaughter of celebrated botanist John Bartram, sold it to Henry Beckett (1791–1871), the son of a British consul in Philadelphia, in 1850. According to scholar Patricia Tyson Stroud, Beckett, “a fervent Francophobe,” moved into the gatehouse and quickly razed Bonaparte’s manor house. He built a new home, which survived until it was destroyed by fire in 1983. The Vincentian Fathers of Philadelphia purchased Point Breeze in 1874 and used it as a summer retreat until 1911, before selling it to the wealthy industrialist Harris Hammond. Point Breeze was repossessed by Hammond’s bank following the 1929 stock market crash and lay derelict for many years. Since 1941 the Divine Word Seminary, a facility for Roman Catholic missionary priests, has occupied the site. Between 2005 and 2012, Point Breeze was the subject of investigation by archaeologists Richard Veit and Michael Gall, who led annual field schools in historic archaeology through Monmouth University and volunteer excavations by members of the Archaeological Society of New Jersey at the site. These investigations documented extant above-ground structures and conducted selective subsurface testing, shedding new light on the history and design of Point Breeze.[13]

—Lacey Baradel

Texts

- Bonaparte, Joseph, September 14, 1817, in a letter to his daughter Zénaïde Bonaparte, describing Point Breeze (quoted in Stroud 2005: 32)[14]

- “I am writing from a room which is the most appealing in the house and perhaps all of the left bank of the Delaware. It has seven windows of which five are on the river. Four times a day the steamboats stop below the windows—I hope that someday I will have the pleasure to be here with you. Today I am all alone.” back up to History

- Wright, Frances, June 1819, in a letter describing Point Breeze (Wright 1821: 99–103)[15]

- “It is a pretty villa, commanding a fine prospect of the river; the soil around it is unproductive; but a step removed from the pine-barren; the pines, however, worthless as they may be, clothe the banks pleasantly enough, and, altogether, the place is cheerful and pretty. Entering upon the lawn, we found the choice shrubs of the American forest, magnolias, kalmias, &c. planted tastefully under the higher trees which skirted, and here and there shadowed, the green carpet upon which the white mansion stood. Advancing, we were now faced at all corners by gods and goddesses in naked, —I cannot say majesty, for they were, for the most part, clumsy enough. . .

- “Until the entrance of the count, who was superintending the additions yet making to the house, we employed ourselves in considering the paintings and Canovas, of which last we found a small but interesting collection. It consists chiefly of busts of the different members of the Buonaparte family. The similar and classic outline prevailing in all is striking, and has truly something imperial in it. . . Turning to look at David’s portrait of Napoleon crossing the Alps, I was greatly disappointed with the expression of the young soldier; the horse has far more spirit than the rider, who sits carelessly on his steed, a handsome beardless boy, pointing his legions up the beetling crags as though they were some easy steps into a drawing room. Such, at least, was my impression. Count Survillier (he wears this title, perhaps, to save the awkwardness of Mr. Bonaparte) soon came to us from his workmen, in an old coat, from which he had barely shaken off the mortar, and, –a sign of the true gentleman, –made no apologies. . . He walked us round his improvements in-doors and out. When I observed upon the amusement he seemed to find in beautifying his little villa, he replied, that he was happier in it than he had ever found himself in more bustling scenes. He gathered a wild flower, and, in presenting it to me, carelessly drew a comparison between its minute beauties and the pleasures of private life; contrasting those of ambition and power with the more gaudy flowers of the parterre, which look better at a distance than upon a nearer approach. He said this so naturally, with a manner so simple, and accent so mild, that it was impossible to see in it attempt at display of any kind. . .” back up to History

- Douglas, David, August 27, 1823, in a journal entry describing Point Breeze (1914: 9)[16]

- “We set off by steamboat at 11 o’clock from Philadelphia to Bordentown. Here stands the house of Joseph Bonaparte, a most splendid mansion, fields well cultivated, pleasure ground laid out in the English style; there are many fine views.”

- Haines, Reuben, July 3, 1825, in a letter to Ann Haines, describing Point Breeze (quoted in Stroud 2002: 137)[17]

- “Drawn by two Elegant Horses along the ever varying roads of the park amidst splendid Rhododendrons on the margin of the artificial lake on whose smooth surface gently glided the majestic European swans. Stopping to visit the Aviary enlivened by the most beautiful English Pheasants, passing by alcoves ornamented with statues and busts of Parian marble, our course enlivened by the footsteps of the tame deer and the flight of the Woodcock, and when alighting stopping to admire the graceful form of two splendid Etruscan vases of Porphyry 3 ft. high & 2 in diameter presented by the Queen of Sweden.” back up to History

- Watson, John Fanning, 1826, describing Point Breeze (quoted in Stroud 2005: 81)[14]

- “Nothing can be more romantic than the whole Scenery–the Shades, where so required, are so very deep & impressive—In the midst of the premises is a beautiful Lake, surrounded by high Banks covered with innumerable Shrubs & Trees–In the middle an Island (artificial) beautifully covered with weeping Willows—Swans & Exotic Geese, sported upon the bosom of the Lake. . . The novelty of such costliness & elegance was like enchantment to my feelings & when I had traversed the various sections of the woods & lawns, through all their charming & meandering avenues & mazes, I could not forbear to think it was the best terrestrial paradise I ever enjoyed.” back up to History

- Trollope, Frances Milton, 1830, describing Point Breeze (1832: 2:153)[18]

- “The country is very flat, but a terrace of two sides has been raised, commanding a fine reach of the Delaware River; at the point where this terrace forms a right angle, a lofty chapel has been erected, which looks very much like an observatory.” back up to History

- Wied, Prince Maximilian, July 19, 1832, describing Point Breeze (2008: 1:73–75)[19]

- “Early on the nineteenth, I undertook a walk to the country home of Louis [sic, Joseph] Bonaparte, ex-king of Spain. It is located 300 paces from Bordentown, not far from the railroad from Amboy, which passes here in the direction of Camden, opposite Philadelphia, and is already sixty miles in length. This road is still under construction, and in sections of the valley, large embankments have been thrown up, as for a highway. . .

- “On the right side of the path, in the region near L. [sic, Joseph] Bonaparte’s country home, I went botanizing. Near a deep ditch in the swamp, with dense thickets and woods on the opposite side, there were magnificent rhododendron shrubs blooming, ten to fifteen and more feet tall, with thick tufts of large, beautiful white or pale reddish flowers and stiff, laurel-like leaves. The young blossoms are rose pink, the older ones almost completely white with a pale shimmer or reddish color. Count Survilliers’ gardener maintains that this is Rhododendron maximum. The shrubs were thickly entangled by wild grapevines. I took all of these plants with me. . .

- “As the day began to cool off, I went to Louis [sic, Joseph] Bonaparte’s country home. The gardener, who was working in the large garden, well and nicely planted with all sorts of European vegetables and fruits, opened the door for me. The county home itself is nice and simple, moderately large with three floors and a flat roof built in this shape [see diagram of house]: ‘a’ is the garden side; ‘b,’ a terrace surrounded with a white railing above a deep ditch, here passing through dark forest. Several heads (probably antiques) have been set up in ‘e.’ A flower garden is found in ‘c,’ before which, closer to the street, the administrative buildings of the superintendent, or manager, and servants are located. In ‘d,’ on the left wing of the house, there is a small, single-story pavilion with glass doors all around. Behind this wing a row of white and red oleander (Nerium), now in bloom, has been planted.

- “I now passed through the entire, very shady, park, which extends on the same level areas along Crosswicks Creek, a rapid brook that flows into the Delaware near Bordentown. On the elevation facing Bordentown, there is a high, narrow pavilion with a small tower and a balcony, from which there must be an excellent view. Around the pavilion there is a terrace with [a] railing from which one enjoys the beautiful view, high over the wooded bank of the river, toward the green region, covered with woods and bushes, through which the Delaware gently glides. From here dark, shady paths go along this tall bank, always on the edge, in twists and turns; this forest, as well as the one shading the mountain face down toward the creek, is magnificent.

- “All the beautiful forest trees of this region, with a now magnificently blooming undergrowth of rhododendron with its white-reddish tufts, provided dark shade. Coniferous and deciduous trees were intermingled. I heard only a few kinds of bird calls here, which seldom came from a few small songbirds but, on the contrary, frequently from catbirds (Turdus felivox Vicill.), which were uncommonly numerous here...

- “An elevated spot on the steep creek bank, mentioned earlier, is interesting. Here in the dark forest, a bridge with a railing has been constructed out over the edge, and beside a stout old hemlock fir (Pinus canadensis), from which I took branches with young fruit, there is a roomy, rectangular platform with benches and railings from which one has an extensive view of the Delaware and its green surroundings, as well as the creek emptying into it at the right and left. Along its banks this rapid brook has extensive strips of an aquatic plant with a shieldlike leaf. And the wooded slope below the park was adorned with the white-reddish flower clusters of the tall rhododendron. Farther away there were rugged pathways in this forest; everywhere the wild grape sent out vines and the rhododendron bloomed. In this park there are also several large fields on which grain had evidently been harvested; other grain was still standing.”

- Gordon, Thomas F., 1834, describing Point Breeze (1834: 106–7)[20]

- “From the brow of the hill, there is a delightful view of the majestic Delaware, pursuing for miles its tranquil course through the rich country which it laves. . . The attractions of the scene determined Joseph Buonaparte, Count de Surveilliers, in his choice of a residence in this country; and this distinguished exile, who has filled two thrones, and has pretensions based on popular suffrage to a third, has dwelt here many years in philosophic retirement. He has in the vicinity of about 1500 acres of land, part of which possessed natural beauty, which his taste and wealth have been employed to embellish. At the expense of some hundred thousand dollars, he has converted a wild and impoverished tract, into a park of surpassing beauty, blending the charms of woodland and plantation scenery, with a delightful water prospect. The present buildings, plain but commodious, are on the site of the offices of his original and more splendid mansion, which was destroyed by fire, together with some rare pictures from the pencils of the first masters, whose merit made them invaluable. With characteristic liberality, the County has opened his grounds to the public, we regret to perceive, that he has been ungratefully repaid, by the defacement of his ornamental structures and mutilation of his statues.” back up to History

- Barber, John Warner, and Henry Howe, 1844, describing Point Breeze (1844: 102–3)[21]

- “The park and grounds of the Count comprise about fourteen hundred acres, which, from a wild and impoverished tract, he has converted into a place of beauty, blending the charms of woodland and plantation scenery with a delightful water-prospect. . . While here, his time was occupied in planning and executing improvements upon his grounds. He did not mingle in society; but was frequently seen walking through his park, attending to his workmen, or, with hatchet in hand, lopping branches from the trees.” back up to History

- Berkley, Helen [Anna Cora Ogden Mowatt Ritchie], 1845, describing Point Breeze (1845: 184–86)[22]

- “We came within sight of his country-seat at eleven o’clock in the morning. I presume you have heard that his former residence had been burnt to the ground; his stables, which were about a quarter of a mile distant, remained uninjured. Their architectural construction was very beautiful and their situation remarkably picturesque. These he had converted into a mansion, hardly inferior in elegance to his former dwelling. The house was long and low, built of stone, and thickly embowered with fine old trees. The expansive folding doors of the front entrance, in spite of their finely-carved workmanship, reminded you that they had once been thrown back to admit horses and carriages instead of the guests which alighted from them. . . The doors at the further end of the hall were open, and displayed several marble fountains flinging their glittering spray over the willows–weeping willows I might say–that gracefully bent around them. We could steal but a hasty glance at the emblematical statues which graced the centre of every fountain. . .

- “About half an hour after the dejeuner, a couple of the count’s carriages drove to the door, and he invited us to take a drive around his grounds. . . I cannot even attempt to give you any idea of the romantic beauty of the grounds, or even of the tasteful manner in which they were laid out. Your imaginations will do them greater justice than any description, and yet will hardly overstep the bounds of reality. If I remember correctly, they are twelve miles round. We visited the site of his former chateau, but every trace of the conflagration had been carefully removed. The only portion of the building left is the observatory, which is surrounded by a stone enclosure and looked like a miniature ruin left purposely in this dilapidated state to add to the picturesqueness of the scene. A narrow stream winds itself gracefully through one part of the grounds, over which several rustic bridges are erected. Equally rustic seats are scattered beneath the shade of the tall trees on its banks, and upon its clear surface a flock of snow-white swans were floating about, diving for fish, or flapping their wings as they bathed their fleecy plumage in the clear stream. A few years ago, a railroad was cut through the count’s property, dividing off one of the pleasantest portions of his grounds. At this he was exceedingly incensed, and could only content himself by building a tunnel beneath the railroad, so that his carriage could drive through without traversing the offensive steam-car path.

- “We occupied several hours in driving about and enjoying the beautiful views. . .

- “The next morning we rose early, and each wrapping herself in a robe de chamber, stole into the garden and wandered for an hour or two through the private pleasure grounds, which we had not yet visited.” back up to History

Images

Thomas Birch, View from the Hill near Bordentown, 1818, Oil on Canvas, 37.5 x 48.5 in, Purchase 2004 Helen McMahon Brady Cutting Fund, Collection of the Newark Museum of Art 2004.12.

Joseph Drayton, View near Bordentown, from the Gardens of the Count de Survilliers, c. 1820.

Thomas Birch, Point Breeze, c. 1820, in Edward J. Nygren, Views and Visions: American Landscape before 1830 (1986), p. 146, pl. 120.

Karl Bodmer (Swiss, 1809-1893), View on the Delaware near Bordentown, 1832, watercolor on paper, Photograph © Bruce M. White, 2019, Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska, Gift of the Enron Art Foundation, 1986.49.24.

After Karl Bodmer (Swiss, 1809-1893), Carl Christian Vogel von Vogelstein, engraver, View on the Delaware near Bordentown, 1839, hand-colored aquatint, Photograph © Bruce M. White, 2019, Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska, Gift of Enron Art Foundation, 1986.49.542.50.

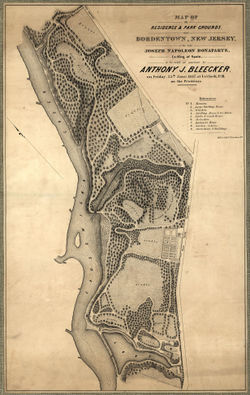

Miller & Co., Map of the residence & park grounds, near Bordentown, New Jersey: of the late Joseph Napoleon Bonaparte, ex-king of Spain, 1847.

Other Resources

The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia

Notes

- ↑ Bonaparte fled to the United States following the abdication and surrender to British forces of his younger brother Napoleon I after the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

- ↑ Although Bonaparte purchased Point Breeze from Sayre, historically the land had been owned by the Farnsworth and Douglas families. Richard Veit and Michael J. Gall, “‘He Will Be a Bourgeois American and Spend His Fortune in Making Gardens’: An Archaeological Examination of Joseph Bonaparte’s Point Breeze Estate,” in Historical Archaeology of the Delaware Valley, 1600–1850, ed. Richard Veit and David Orr (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2014), 299, view on Zotero. For the full ownership history of the property between 1681 and Bonaparte’s purchase of it in 1816, see United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, National Register of Historic Places—Nomination Form, “Point Breeze,” February 1977, 6, 8, view on Zotero. Bonaparte hired Theodore Mauroy, a master mason whom he had employed previously at his residence Mortefontaine in France, to design the new home, although Bonaparte largely oversaw the construction process himself. Stephen Girard, an entrepreneur, financier, and philanthropist, helped Bonaparte acquire high-quality building supplies, including Carolina pine and imported marble. Bonaparte moved into the house by August 1817. Patricia Tyson Stroud, The Man Who Had Been King: The American Exile of Napoleon’s Brother Joseph (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005), 23–24, 58, view on Zotero; and Veit and Gall 2014, 300, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bonaparte’s first land purchases had to be made through his agent, James Carret, because Bonaparte was not a United States citizen. However, the law changed in 1817, when New Jersey permitted non-naturalized foreigners from countries not at war with the United States to hold real estate. Stroud 2005, 23, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bonaparte’s collection of art and furnishings was very large; one 1818 memorandum lists nineteen cases of paintings, engravings, furniture, rugs, candelabra, sconces, mirrors, clocks, maps, table linens and kitchenware that Bonaparte shipped from Le Havre to Philadelphia. Stroud 2005, 57, view on Zotero. Paintings in the collection included, among others, a version of Jacques Louis David’s Bonaparte Crossing the Alps (1801) commissioned by Charles IV of Spain; Frans Snyders’s Two Lions and a Fawn; Charles Joseph Natoire’s La Toilette de Psyche (1745; New Orleans Museum of Art); Noël Nicolas Coypel’s Rape of Europa (1726–1727; Philadelphia Museum of Art); and various portrait statues and paintings of the Bonaparte family by artists such as Lorenzo Bartolini (1777–1850), Antonio Canova (1757–1822), Raimondo Trentanove (1792–1832), and François Gérard. Bonaparte often loaned artworks to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts’s annual exhibitions, making his collection even more widely accessible to the public. Bonaparte’s library included approximately eight thousand volumes, compared to the 6,500 in the Library of Congress during this period. Patricia Tyson Stroud, “Point Breeze: Joseph Bonaparte’s American Retreat,” Magazine Antiques 162, no. 4 (October 2002): 133–34, 136, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Stroud 2005, 74, 77, view on Zotero. Mortefontaine was located adjacent to Ermenonville, an estate belonging to the Marquis René-Louis Girardin (1735–1808), an eighteenth-century theorist of picturesque gardens whose ideas informed the design of the gardens at Mortefontaine. Ermenonville and Mortefontaine also informed Bonaparte’s landscape design for Point Breeze. See Constance A. Webster, “Bonaparte’s Park: A French Picturesque Garden in America,” Journal of Garden History 6, no. 4 (October–December 1986): 330–47, view on Zotero; and Constance A. Webster, “Recreating an American Landscape: Joseph Bonaparte’s Park at Point Breeze,” Journal of the New England Garden History Society 4 (Spring 1996): 14–15, view on Zotero. According to Stroud, the design also reflected Bonaparte’s familiarity with the gardens at El Escorial, the sixteenth-century palace of Philip II (1527–1598) located northwest of Madrid. Stroud 2005, 78, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Webster 1986, 330, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Stroud 2005, 59, 78, 80, view on Zotero; Stroud 2002, 137, view on Zotero; and Veit and Gall 2014, 302, view on Zotero. In the winter, Bonaparte and his guests used the frozen lake for ice skating. Webster 1996, 16, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Stroud 2005, 78–80; quote on 79, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bonaparte was away from Point Breeze when the fire broke out, but, thanks to the efforts of the people of Bordentown, most of his collection was saved. Stroud 2005, 46–7, 62–66, 71, view on Zotero; and Veit and Gall 2014, 300, view on Zotero.

- ↑ The Lake House was connected to the manor house by a forty-foot subterranean passage as well as a lattice-covered arcade. Stroud 2005, 81, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Veit and Gall 2014, 306–8, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Stroud 2005, 81, view on Zotero; and Veit and Gall 2014, 300, 302, 310, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Stroud 2005, 218–19, view on Zotero; and Rev. Raymond Lennon, "The Bordentown Story, 1941–2012," Chicago Province, 2014, view on Zotero. According to Veit and Gall, Hammond had hired the noted Ashcan artist Everett Shinn to help reconstruct the Bonaparte-era landscape at Point Breeze, but the plan was never executed due to Hammond’s losses in the 1929 stock market crash. Veit and Gall 2014, 297, 302, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Stroud 2005, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Frances Wright, Views of Society and Manners in America; in a Series of Letters from that Country to a Friend in England, During the Years 1818, 1819, and 1820 (New York: E. Bliss and E. White, 1821), view on Zotero.

- ↑ David Douglas, Journal Kept by David Douglas During His Travels in North America 1823–1827 Together with a Particular Description of Thirty-Three Species of American Oaks and Eighteen Species of Pinus, with Appendices Containing a List of the Plants Introduced by Douglas and an Account of His Death in 1834 (London: W. Wesley & Son, for the Royal Historical Society, 1914), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Stroud 2002, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Frances Milton Trollope, Domestic Manners of the Americans, 3rd ed., 2 vols. (London: Wittaker, Treacher, 1832), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Maximilian of Wied, The North American Journals of Prince Maximilian of Wied, Volume 1, May 1832–April 1833, edited by Stephen S. Witte and Marsha V. Gallagher (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas F. Gordon, A Gazetteer of the State of New Jersey (Trenton, NJ: Daniel Fenton, 1834), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Warner Barber and Henry Howe, Historical Collections of the State of New Jersey; Containing a General Collection of the Most Interesting Facts, Traditions, Biographical Sketches, Anecdotes, &c. Relating to History and Antiquities, with Geographical Descriptions of Every Township in the State (Newark, NJ: Benjamin Olds, 1844), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Helen Berkley, “A Sketch of Joseph Buonaparte,” Godey’s Lady’s Book 30 (April 1845): 184–87, view on Zotero.