Mount

See also: Mound

History

The term mount connoted raised features in both the natural and designed landscape, but in landscape-design vocabulary it usually signified an artificial hill, and is closely related to that of mound. The two were used in similar and, at times, synonymous ways. For instance, the features at William Middleton’s plantation Crowfield, near Charleston, and the Hermitage appear from descriptions to have been very similar, yet one is described in 1743 as a mount and the other in 1801 as a mound. In general, “mount” was the preferred term of garden treatise writers, perhaps owing to their familiarity with foreign terms such as mont (French) and monte (Italian) or the tradition of mounts in medieval and Renaissance gardens. In contrast, American observers tended to use the term “mound” to describe what English travelers, such as William Eddis, called mounts. Yet, there were also subtle distinctions in their usage. Unlike “mound,” the term “mount” also carried the connotation of a hill, mountain, or natural elevation, as exemplified by Isaac Weld’s 1799 account of Mount Vernon, Augustus John Foster’s 1812 description of Monticello, and Charles Trego’s 1843 depiction of Fairmount Waterworks in Philadelphia. A. J. Downing in 1849 also noted on the grounds of William Harrison’s Cheshunt Cottage, near London, a mount where a cluster of agave plants had taken root. Perhaps because of this association with European usage and with natural elevations, the term “mount” was commonly employed in place names such as Mount Auburn Cemetery, Mount Vernon and Daniel Wadsworth’s Monte Video, in Avon, Connecticut. Despite these subtleties of usage, however, there appears to have been no difference in the reference to shape, planting, or function implied by the two terms when used to describe an artificial hill in a garden setting.

—Elizabeth Kryder-Reid

Texts

Usage

- Pinckney, Eliza Lucas, c. May 1743, in a letter to Miss Bartlett, describing Crowfield, plantation of William Middleton, vicinity of Charleston, SC (1972: 61)[1]

- “. . . come to the bottom of this charming spott where is a large fish pond with a mount rising out of the middle—the top of which is level with the dwelling house and upon it is a roman temple.”

- Hamilton, Alexander, August 21, 1744, describing Malbone Hall, country seat of Godfrey Malbone, Newport, RI (1948: 153)[2]

- “I walked out betwixt 12 and one with Dr. Moffat an[d] viewed Malbone’s house and gardens. We went to the lanthern, or cupola att top, from which we had a pritty view of the town of Newport and of the sea towards Block Island, and behind the house, of a pleasant mount gradually ascending to a great height from which we can have a view of almost the whole island.”

- Eddis, William, October 1, 1769, describing the Governor’s House, Annapolis, MD (1792: 17)[3]

- “The garden is not extensive, but it is disposed to the utmost advantage; the centre walk is terminated by a small green mount, close to which the Severn approaches; this elevation commands an extensive view of the bay, and the adjacent country. . . there are but few mansions in the most rich and cultivated parts of England, which are adorned with such splendid and romantic scenery.”

- Bartram, William, 1791, describing the area north of Wrightsborough, GA (1928: 56–57)[4]

- “. . . many very magnificent monuments of the power and industry of the ancient inhabitants of these lands are visible. I observed a stupendous conical pyramid, or artificial mount of earth, vast tetragon terraces, and a large sunken area, of a cubical form, encompassed with banks of earth; and certain traces of a larger Indian town, the work of a powerful nation, whose period of grandeur perhaps long preceded the discovery of this continent. . .

- “old Indian settlements, now deserted and overgrown with forests. These are always on or near the banks of rivers, or great swamps, the artificial mounts and terraces elevating them above the surrounding groves.”

- Bartram, William, 1791, describing an island off of Lake George, GA (1928: 104)[4]

- “On the site of this ancient town, stands a very pompous Indian mount, or conical pyramid of earth, from which runs in a straight line a grand avenue or Indian highway, through a magnificent grove of magnolias, live oaks, palms, and orange trees, terminating at the verge of a large green level savanna.”

- Weld, Isaac, 1799, describing Mount Vernon, plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (1799: 53)[5]

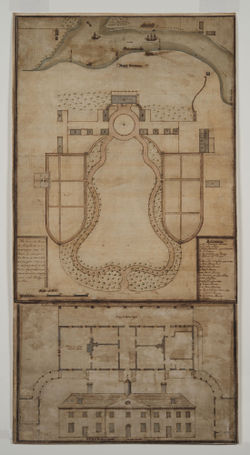

- “The ground in the rear of the house is also laid out in a lawn, and the declivity of the Mount, towards the water, in a deer park.” [Fig. 1]

- Foster, Sir Augustus John, 1812, describing Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, VA (1954: 144)[6]

- “. . . the house which is build on a level platform that was formed by the President’s father who cut down the top of the mount to the extent of about two acres.”

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), December 1839, describing Cheshunt Cottage, property of William Harrison, near London, England (Gardener’s Magazine 15: 667–68)[7]

- “The masses of trees and shrubs are chiefly on the mount near the lake, and along the margin which shuts out the kitchen-garden; and in these places they are planted in the gardenesque manner, so as to produce irregular groups of trees, with masses of evergreen and deciduous shrubs as undergrowth, intersected by glades of turf. They are scattered over the general surface of the lawn, so as to produce a continually varying effect, as viewed from the walks; and so as to disguise the boundary, and prevent the eye from seeing from one extremity of grounds to the other, and thus ascertain their extent.”

- Trego, Charles, 1843, describing Fairmount Waterworks, Philadelphia, PA (1843: 322)[8]

- “The mount is an oval shaped eminence, and on its top, which is 102 feet above the water in the river, and upwards of 50 feet above the highest ground in the city, are four reservoirs containing together about 22,000,000 of gallons.” [Fig. 2]

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1849, describing Cheshunt Cottage, property of William Harrison, near London, England (1849; repr., 1991: 517)[9]

- “The masses of trees and shrubs are chiefly on the mount near the lake, and along the margin which shuts out the kitchen-garden; and in these places they are planted in the gardenesque manner, so as to produce irregular groups of trees, with masses of evergreen and deciduous shrubs as undergrowth, intersected by glades of turf. They are scattered over the general surface of the lawn, so as to produce a continually varying effect, as viewed from the walks; and so as to disguise the boundary, and prevent the eye from seeing from one extremity of the grounds to the other, and thus ascertain their extent.”

Citations

- Parkinson, John, 1629, Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris (1629; repr., 1975: 5)[10]

- “For there may be therein [the garden]. . . a rocke or mount, with a fountaine in the midst thereof to convey water to every part of the Garden.”

- Switzer, Stephen, 1718, Ichnographia Rustica (1718; repr., 1982: 3:xi)[11]

- “Earth ever there is to spare by the digging of Cellars and the like, ought to be carry’d to some convenient Place, and a Mount made, and planted round promiscuously with Greens, Trees, &c. This will afford a good Prospect from several Parts of a Garden, and by going up to the Top an agreeable view about an Estate, and this is more particularly necessary where the Scituation [sic] of a House is on a large Flat.”

- Langley, Batty, 1728, New Principles of Gardening (1728; repr., 1982: vi–vii, 195–99)[12]

- “When the Situation of Gardens such, that the making of Slopes and Terraces are necessary, or cannot be avoided, they not only leave them naked of Shade as aforesaid, but break their Slopes into so many Angles, that their native Beauty is thereby destroy’d. Thus if by waste Earth a Mount be raised ten or twelve Feet high, you shall have its Slope, that should be entire from top to bottom, broken into three, if not four small trifling ones, and those mixt with Archs of Circles, &c. that still adds to their ill Effects: So that instead of having one grand Slope only with an easy Ascent, you have three or four small ones, that are poor and trifling.

- “And the only reason why they are made in this Stair or Step-like manner, is first to shew their Dexterity of Hand, without considering the ill Effect; and lastly to imitate those grand Amphitheatrical Buildings, used by the Ancients, of which they had no more Judgement, than of the excellent Proportions of Architecture that was used therein, when those noble Structures were first erected.

- “General DIRECTIONS, &c. . .

- “XII. That Earths cast out of Foundations, &c. be carried to such Places for raising of Mounts, from which, fine Views may be seen.

- “XIII. That the Slopes of Mounts, &c. be laid with a moderate Reclination, and planted with all Sorts of Ever-Greens in a promiscuous Manner, so as to grow all in a Thicket; which has a prodigious fine Effect.

- “In this very Manner are planted two beautiful Mounts in the Gardens of the Honourable Sir Fisher Tench at Low-Layton in Essex.

- “XIV. That the Walks leading up the Slope of a Mount, have their Breadth contracted at the Top, full one half Part; and if that contracted Part be enclosed on the Sides with a Hedge whose Leaves are of a light Green, ’twill seemingly add a great Addition to the Length of the Walk, when view’d from the other End. . .

- “XXI. Such Walks as must terminate within the Garden, are best finish’d with Mounts.”

- Chambers, Ephraim, 1743, Cyclopaedia (1743: 2:n.p.)[13]

- “MOUNT, an elevation of earth, called also mountain. See MOUNTAIN.

- The words mount and mountain are synonymous.”

- Johnson, Samuel, 1755, A Dictionary of the English Language (1755: 2:n.p.)[14]

- “MOUNT. n.s. [mont, French; mons, Latin.] . . .

- “2. An artificial hill raised in a garden, or other place.”

- M’Mahon, Bernard, 1806, The American Gardener’s Calendar (1806: 59, 64)[15]

- “In other parts are sometimes discovered eminences, or rising grounds, as a high terrace, mount, steep declivity, or other eminence, ornamented with curious trees and shrubs, with walks leading under the shade of trees, by easy ascents to the summit, where is presented to the view, an extensive prospect of the adjacent fields, buildings, hamlets, and country around, and likewise affording a fresh and cooling air in summer. . .

- “Fountains and statues, are generally introduced in the middle of spacious opens; statues are also placed at the terminations of particular walks, sometimes in woods, thickets, and recesses, upon mounts, terraces, and other stations, according to what they are intended to represent.”

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828: 2:n.p.)[16]

- “MOUNT, n. [Fr. mont; Sax. munt; It. Port. Sp. monte; Arm. menez, mene; W. munt, a mount, mountain or mound, a heap; L. mons, literally a heap or an elevation. Ir. moin or muine; Basque, mendia. . .]

- “1. A mass of earth, or earth and rock, rising considerably above the common surface of the surrounding land. Mount is used for an eminence or elevation of earth, indefinite in highth [sic] or size, and may be a hillock, hill or mountain. We apply it to Mount Blanc, in Switzerland, to Mount Tom and Mount Holyoke, in Massachusetts, and it is applied in Scripture to the small hillocks on which sacrifice was offered, as well as to Mount Sinai. Jacob offered sacrifice on the mount or heap of stones raised for a witness between him and Laban. Gen. xxxi.

- “2. A mound; a bulwark for offense or defense.”

Images

Inscribed

Batty Langley, "Variety of Lawns, or Openings, before a grand Front of a Building, into a Park, Forest, Common, &c." in New Principles of Gardening, or The laying out and planting parterres, groves, wildernesses, labyrinths, avenues, parks, &c. (1728), pl. XVI. "Mount" inscribed around the circular shape at right.

Samuel Vaughan, Plan of Mount Vernon, 1787.

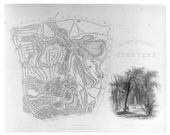

William Bartram, A great mound and its avenues, at Mount Royal, near Lake George, Georgia, in “Observations on the Creek and Cherokee Indians” (1789), from Transactions of the American Ethnological Society 3, part 1 (1853): 57, fig. 6.

George Isham Parkyns, Mount Vernon, 1795.

Anonymous, “Mount Auburn,” in American Magazine of Useful and Entertaining Knowledge 1, no. 10 (June 1835): 450.

John T. Bowen, A View of the Fairmount Water-Works with Schuylkill in the distance, taken from the Mount, 1838.

James Smillie (artist), John A. Rolph (engraver), “Indian Mound,” in Nehemiah Cleaveland, Green-Wood Illustrated (1847), opp. 19.

James Smillie, “Mount Auburn Cemetery,” in Cornelia W. Walter, Mount Auburn Illustrated (1847; repr., 1850), frontispiece. Mount inscribed at bottom of map.

James Smillie (artist) and John A. Rolph (etcher), “View of the Pilgrim Path, Mount Auburn Cemetery,” in Cornelia W. Walter, Mount Auburn Illustrated (1847; repr., 1850), opp. 10.

Anonymous, Boat House and Agave Mount, in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America, 4th ed. (1849), 517, fig. 17.

Frederick Graff, Plan of Lemon Hill and Sedgley Park, Fairmount and Adjoining Property, October 15, 1851.

Associated

William Bartram, “Plan of the Ancient Chunky-Yard,” in “Observations on the Creek and Cherokee Indians” (1789), Transactions of the American Ethnological Society (1853) 3, part 1: 52, fig. 2.

Attributed

Batty Langley, “Design of a Garden and Wilderness in an Island,” in New Principles of Gardening (1728), pl. XV.

Notes

- ↑ Eliza Lucas Pinckney, The Letterbook of Eliza Lucas Pinckney, 1739–1762, ed. Elise Pinckney (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1972), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alexander Hamilton, Gentleman’s Progress: The Itinerarium of Dr. Alexander Hamilton, 1744, ed. Carl Bridenbaugh (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1948), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Eddis, Letters from America: Historical and Descriptive; Compromising Occurances from 1769 to 1777 Inclusive (London: Printed for the author, 1792), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 William Bartram, Travels through North and South Carolina, Georgia, East and West Florida, ed. Mark Van Doren (New York: Dover, 1928), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Isaac Weld, Travels through the States of North America and the Provinces of Upper and Lower Canada, during the Years 1795, 1796, and 1797 (London: John Stockdale, 1799), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Sir Augustus John Foster, Jeffersonian America: Notes on the United States of America Collected in the Years 1805–1806–1807 and 1811–1812, ed. Richard Beale Davis (San Marino, CA: Huntington Library, 1954), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. Loudon, “Descriptive Notices of Select Suburban Residences, with Remarks on Each; Intended to Illustrate the Principles and Practices of Landscape-Gardening,” Gardener’s Magazine and Register of Rural & Domestic Improvement 15, no. 117 (December 1839): 633–74, view on Zotero

- ↑ Charles B. Trego, A Geography of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia: Edward C. Biddle, 1843), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America, 4th ed. (1849; repr., Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Parkinson, Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris (1629; repr., Norwood, NJ: W.J. Johnson, 1975), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Stephen Switzer, Ichnographia Rustica, or The Nobleman, Gentleman and Gardener’s Recreation. . . , 1st ed., 3 vols. (London: D. Browne, 1718), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Batty Langley, New Principles of Gardening, or The Laying out and Planting Parterres, Groves, Wildernesses, Labyrinths, Avenues, Parks, &c. (London: A. Bettesworth and J. Batley, etc., 1728; repr., New York: Garland, 1982), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Ephraim Chambers, Cyclopaedia, or An Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences. . . , 5th ed., 2 vols. (London: D. Midwinter et al., 1741), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language: In Which the Words Are Deduced from the Originals and Illustrated in the Different Significations by Examples from the Best Writers, 2 vols. (London: W. Strahan for J. and P. Knapton, 1755), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bernard M’Mahon, The American Gardener’s Calendar: Adapted to the Climates and Seasons of the United States. Containing a Complete Account of All the Work Necessary to Be Done. . . for Every Month of the Year. . . (Philadelphia: Printed by B. Graves for the author, 1806), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero.