Mound

See also: Mount

History

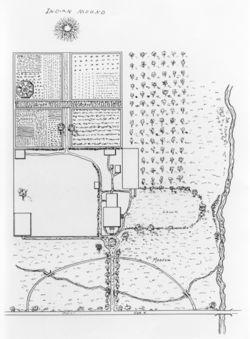

The term mound connoted raised features in both the natural and designed landscape, but in landscape-design vocabulary it usually signified an artificial hill. Both Ephraim Chambers's Cyclopaedia (1741–43) and Noah Webster's An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828) defined a mound as a bank of earth. In common usage it usually denoted a rounded or conical elevation of earth. Native Americans in the eastern half of the United States had built mounds for millennia [Fig. 1]. While the similarity in form links these prehistoric conical and platform mounds to the mounds created in American gardens, differences in their scale and use suggest various meanings in each context. Native American mounds were used for burials and, in the case of larger platform mounds, for elite residences and sacred areas. In European and American gardens, mounds were used as observation places or as an ornamental variety of surface. Garden mounds or mounts, which appear to have been built mainly in the late 18th through mid-19th centuries, were planted with grass, ground cover, shrubs, trees, or a combination of these materials.[1] For example, the mound at the Elias Hasket Derby Farm in Peabody, Massachusetts, was turfed, while at Mount Vernon in Fairfax Country, Virginia, willow trees and at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts, evergreens were planted. Periwinkle was recommended by the New England Farmer in 1841 as a ground cover for mounds; and grass, altheas, gelder roses, lilacs, calycanthus, weeping willows, and aspens were planted on the mounds at Thomas Jefferson's Poplar Forest in Bedford County, Virginia.

The relatively simple form of a mound of earth or earth and stone was used as a design element in American gardens to achieve a variety of purposes or effects. Mounds were sometimes used for the base of a garden house, such as the brick study or chapel described in 1801 at John Burgwin’s Hermitage, in Wilmington, North Carolina. Not only did the mound’s elevated position enhance the structure as a viewing platform, but it also served as a focal point within the garden. Furthermore, symmetrically placed mounds could be used to frame distant views, as at Mount Vernon, or to frame a house, as at Poplar Forest. The mounds at Poplar Forest were connected to the house with double rows of poplars, which functioned visually like hyphens. Mounds may also have been added to provide sculptural relief and visual interest to relatively flat areas, as in the yard at the State House Yard in Philadelphia, which the Rev. Manasseh Cutler described in 1787. This use of mounds was occasionally controversial; C. M. Hovey described the much-criticized mounds on the grounds of the White House in Washington, DC, in an 1842 issue of the Magazine of Horticulture. A mound offered a slope against which to plant, creating much the same effect as plants of successive height arrayed in a shrubbery. In this way, a mound allowed the viewer at ground level to see the pattern of the plantings in much the same way an elevated view allowed one to appreciate the intricacies of a flat parterre.[2]

Several extant and archaeological examples also indicate that small mounds were often created in the construction of domestic icehouses, as Thomas Moore advised in his 1803 treatise.[3] Mounds provided insulation and were also a convenient way to use fill that had been excavated for the ice pit. While not using the term “mound,” George Washington noted in his diary in December of 1785 that he had “[f]inished covering my Ice House with dirt and [the] sodding of it.”[4] Several images, from about that time, show what appear to be mounds, particularly those near a main house; these may have been icehouse mounds [Fig. 2]. Mounds were also associated with burials, as seen in James Smillie’s engraving of the “Indian Mound” at Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York [Fig. 3], or the mound at Mount Auburn Cemetery, which, according to H. A. S. Dearborn (1832), harkened back to the ancient tumuli of Troy.

—Elizabeth Kryder-Reid

Texts

Usage

- Washington, George, 1786, describing Mount Vernon, plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (Jackson and Twohig, eds., 1978: 4:267, 293)[5]

- “[January 25] And set about the Banks round the Lawn, in front of the gate between the two Mounds of Earth. . . [Fig. 4]

- “[March 13] The ground being in order for it, I set the people to raising and forming the mounds of Earth by the gate in order to plant weeping willow thereon.”

- Cutler, Manasseh, July 13, 1787, describing the State House Yard, Philadelphia (1987: 1:262)[6]

- “It was so lately laid out in its present form that it has not assumed that air of grandeur which time will give it. The trees are yet small, but most judiciously arranged. The artificial mounds of earth, and depressions, and small groves in the squares have a most delightful effect.”

- Constantia [Judith Sargent Murray], June 24, 1790, “Description of Gray’s Gardens, Pennsylvania” (Massachusetts Magazine 3: 415)

- “On one hand, the lovely valley richly shaded, is fancifully adorned, the mountain laurel condescending to flourish there—and on the other, grass grown mounds variegate the view. . . At every turn shaded seats are artfully contrived, and the ground abounds with arbours, alcoves, and summer houses, which are handsomely adorned with odoriferous flowers. Among these the little federal temple claims the principal regard. It is the very edifice, that upon the celebration of the ratification of the constitution, was carried in triumphant procession through the streets of this metropolis; and, upon a gentle acclivity, upon the summit of a green mound infixed, it hath now obtained a basis.”

- Bartram, William, 1791, describing Indian settlements in North Carolina, Georgia, and Florida (1996: 566–67)[8]

- “In the Cherokee country, all over Carolina, and the Northern and Eastern parts of Georgia, wherever the ruins of ancient Indian towns appear, we see always beside these remains one vast, conical-pointed mound. To mounds of the kind I refer when I speak of pyramidal mounds. To the south and west of the Altamaha, I observed none of these in any part of the Muscogulge country, but always flat or square structures. The vast mounds upon the St. John’s, Alachua, d Musquito [sic] rivers, differ from those amongst the Cherokee with respect to their adjuncts and appendages, particularly in respect to the great highway or avenue, sunk below the common level of the earth, extending from them, and terminating either in a vast savanna or natural plain, or an artificial pond or lake. A remarkable example occurs at Mount Royal, from whence opens a glorious view of Lake George and its environs.

- “Fig. 6 is a perspective plan of this great mound and its avenues, the latter leading off to an expansive savanna or natural meadow. A, the mound, about forty feet in perpendicular height; B, the highway leading from the mound in a straight line to the pond C, about a half a mile distant. . . The sketch of the mound also illustrates the character of the mounds in the Cherokee country; but the last have not the highway or avenue, and are always accompanied by vast square terraces, placed upon one side or the other. On the other hand, we never see the square terraces accompanying the high mounds of East Florida.” [Fig. 5]

- Clitherall, Eliza Caroline Burgwin, active 1801, describing the Hermitage, seat of John Burgwin, Wilmington, NC (quoted in Flowers 1983: 126)[9]

- “In a small brick building called the study, on a high mound in the Big Garden, was a fine collection of books, writing desk and tables.”

- Southgate, Eliza, July 6, 1802, describing Elias Hasket Derby Farm, Peabody, MA (quoted in Kimball 1940: 76)[10]

- “. . . at the upper end of the garden there was a beautiful arbour formed of a mound of turf and ’twas surrounded by a thick row of poplar trees which branched out quite to the bottom and so close together that you could not see through.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, February 1811–13, describing Poplar Forest, property of Thomas Jefferson, Bedford County, VA (quoted in Chambers 1993: 69)[11]

- “[February 1811] Memom. plant on each mound 4. weeping willows on the top in a square 20 f. apart. Golden Willows in a circle round middle. 15. f. apart. Aspens in a circle round the foot. 15.f. apart. . .”

- Dearborn, H. A. S., 1832, describing Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, MA (quoted in Harris 1832: 76)[12]

- “The approach from the main road leading to Watertown, was by a broad and umbrageous avenue to the foot of the hill, which closes the dale of consecration on the north. This small eminence was thickly overgrown with pines and cedars, but the lower limbs having been pruned, the symmetrical contour of the mound was disclosed, and it assumed the appearance of an ancient tumulus, reared to the memory of some great chieftain, like that of Achilles, of Ajax, and of Patroclus, on the plains of Troy.”

- Walsh, Alexander, March 31, 1841, “Remarks on Ornamental Gardening” (New England Farmer 19: 308)[13]

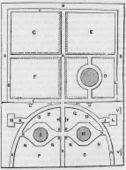

- “H and I two mounds 12 inches diameter, 3 feet 6 inches high, enclosed by octagons, leaving a walk 4 feet in the narrowest part, with openings of 6 feet to the centre walk and elipsis [sic]; the mounds enclosed with brick, placed endwise, inclining to the centre, and sunk 3 inches in the ground; the enclosure filled with soil; each mound has growing in its centre an evergreen tree. H covered with evergreen periwinkle, Vica minor, and I covered with variegated periwinkle, Vica minor fl. alba.” [Fig. 6]

- Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), April 1842, “Notes made during a Visit to New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, &c.,” describing the White House, Washington, DC (Magazine of Horticulture 8: 128–29)[14]

- “The garden consists of nothing but a plain piece of ground, formerly quite level, but now made uneven and unmeaning by three artificial mounds. . . The mounds which we have referred to have been thrown up, and thus remain, without any plantations of shrubs or trees to give a character to the garden, or hide the nakedness of these elevations, seeming more like heaps of earth accidentally placed there, and grown with turf, rather than the natural undulations of the surface. We can conceive of no worse taste than the execution of the work as it now is: the object of these mounds seems to have been to hide one part of the garden from another.”

Citations

- Chambers, Ephraim, 1741–43, Cyclopaedia (1743: 2:n.p.)[15]

- “MOUND, a term used for a bank, rampart, or other fence, particularly of earth.”

- Moore, Thomas, 1803, An Essay on the Most Eligible Construction of Ice-houses (1803: 13)[16]

- “In level situations, where a drain cannot be conveniently dug out from the bottom of the pit; I should suppose it would answer very well to enclose the ice by a mound raised entirely above the surface of the earth, through which the water may be discharged. . . This perhaps would not be quite so cool a repository as if under the surface of the earth; unless the mound was very thick; but I am persuaded that the loss of a few degrees in temperature bears very little proportion to the advantage resulting from dryness.”

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828: 2:n.p.)[17]

- “MOUND, n. [Sax. mund; W. mwnt, from mwn; L. mons. See Mount.]

- “Something raised as a defense or fortification, usually a bank of earth or stone; a bulwark; a rampart or fence.

- “God has thrown

- “That mountain as his garden mound, high raised. Milton.

- “To thrid the thickets or to leap the mounds. Dryden.”

Images

Inscribed

William Bartram, “Plan of the Ancient Chunky-Yard,” in “Observations on the Creek and Cherokee Indians” (1789), from Transactions of the American Ethnological Society 3, part 1 (1853): 52, fig. 2. “B, a circular eminence. . . upon this mound stand a great Rotunda, Hot house, or Winter Council House of the present Creeks.”

William Bartram, A great mound and its avenues, at Mount Royal, near Lake George, Georgia, in “Observations on the Creek and Cherokee Indians” (1789), from Transactions of the American Ethnological Society 3, part 1 (1853): 57, fig. 6.

Associated

Samuel Vaughan, Plan of Mount Vernon, 1787.

George Isham Parkyns, Mount Vernon, 1795.

Anonymous, “Mount Auburn,” in American Magazine of Useful and Entertaining Knowledge 1, no. 10 (June 1835): 450.

Attributed

Batty Langley, “Design of a Garden and Wilderness in an Island,” in New Principles of Gardening (1728), pl. XV.

Notes

- ↑ Although the first usage noted in this study is George Washington’s 1786 diary entry, Eliza Lucas Pinckney’s description in 1743 of the mount in William Middleton’s garden suggests that similar garden features were built earlier in the century, even if they were not identified as mounds. In addition, Native American mounds predate the first English-language accounts by nearly half a millennia.

- ↑ This observation has been made about English shrubberies in Mark Laird, “Ornamental Planting and Horticulture in English Pleasure Grounds, 1700–1830,” in Garden History: Issues, Approaches, Methods, ed. John Dixon Hunt (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1992), 257, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Examples of icehouses with mounds include the Governor’s Palace, Williamsburg, VA, and General Charles Ridgely’s estate, Hampton, in Baltimore County, Maryland.

- ↑ George Washington, The Diaries of George Washington, ed. Donald Jackson and Dorothy Twohig, 6 vols. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1978), 4:244, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Washington in Jackson and Twohig 1978, view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Parker Cutler, Life, Journals, and Correspondence of Rev. Manasseh Cutler, LL.D. (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1987), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Constantia [Judith Sargent Murray], “Description of Gray’s Gardens, Pennsylvania,” Massachusetts Magazine, or, Monthly Museum of Knowledge and Rational Entertainment 7, no. 3 (July 1791): 413–17, view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Bartram, Travels, and Other Writings, ed. Thomas Slaughter (New York: Library of America, 1996), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Flowers, “People and Plants: North Carolina’s Garden History Revisited,” Eighteenth Century Life 8 (1983): 117–29, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Fiske Kimball, Mr. Samuel McIntire, Carver, the Architect of Salem (Portland, ME: Southworth-Anthoensen, 1940), view on Zotero.

- ↑ S. Allen Chambers Jr., Poplar Forest and Thomas Jefferson (Forest, VA: Corporation for Jefferson’s Poplar Forest, 1993), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thaddeus William Harris, A Discourse Delivered before the Massachusetts Horticultural Society on the Celebration of Its Fourth Anniversary, October 3, 1832 (Cambridge, MA: E. W. Metcalf, 1832), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alexander Walsh, “Remarks on Ornamental Gardening, With a Plan of a Fruit, Flower and Vegetable Garden,” New England Farmer, and Horticultural Register 19, no. 39 (March 31, 1841): 308–9, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Mason Hovey, “Notes Made during a Visit to New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington, and Intermediate Places, from August 8th to the 23rd, 1841,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 8, no. 4 (April 1842): 121–29, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Ephraim Chambers, Cyclopaedia, or An Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences. . . , 5th ed., 2 vols. (London: D. Midwinter et al., 1741–43), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Moore, An Essay on the Most Eligible Construction of Ice-Houses (Baltimore: Bonsal and Niles, 1803), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero.