Arcade

History

According to lexicographers, an arcade was a series of joined arches that could be used to support a roof and thus create a covered area or walk. Arcades created architectural and aesthetic links from the main building to side or outbuildings that were often situated away from the principal structure for practical reasons (for example, kitchens, which were typically located at some distance from the house to prevent the spread of fire). As connectors, arcades provided covered walkways, as well as channels of cooled air that circulated from ancillary structures to the main building.

The arcade form derived from antiquity and had been revived in the modern era, particularly in the work of Italian architect Andrea Palladio. From the late 17th century onward, Palladian-inspired architecture spread throughout continental Europe, England, and America, popularized in part through pattern books, which often feature the arcade form. The Capitol in Williamsburg, which utilized an arcade to link the two wings of the building, served as a model for several 18th-century public buildings in Virginia [Fig. 1].[1] Arcades were also found in early 19th-century campus designs, such as Joseph Jacques Ramée’s plan for Union College in Schenectady, New York, and Thomas Jefferson’s work at the University of Virginia, both of which became important precedents in this field [Figs. 2 and 3]. Here arcades helped to establish the framework of the campus and to enclose and define common space. A number of significant and well-known private dwellings, including Mount Vernon, Peacefield, and the White House also included arcades that made direct reference to Palladian designs and became models for subsequent builders, even up to the present day.

The significance of arcades for landscape design was rarely articulated by contemporary observers of American architecture, yet visual representations of sites employing arcades make plain the role such structures played in shaping their surroundings. At Mount Vernon, the open arcades that Washington built between his house and the neighboring outbuildings allowed him to maintain views of the Potomac (considered one of the chief sources of beauty at his estate) from the western side of the house [See Fig. 6]. Glimpses of water, land, and vegetation afforded by these arches helped to situate the house in the landscape, visually linking the house and its outbuildings to the shrubbery-lined walks on the land side of the house and the park landscape on the river side of the house. In the case of the White House, Anne-Marguerite-Henriette Rouillé de Marigny Hyde de Neuville's sketch of 1821 shows the arcades as arms extending out from the main structure into the landscape, visually and conceptually connecting the house to the grounds [Fig. 4].

Arcades also operated as viewing platforms, much like porches, pavilions, and other covered garden structures. In A. J. Downing's designs, for example, arcades were often placed where porches or verandas might also be situated. In fact, the term “arcade” was often elided with “porch” or “veranda.” A covered, open-air extension of the house, the arcade was also similar to a piazza, and structures resembling arcades in the colonial period were often referred to as piazzas. A case in point is an example from Batty Langley’s Gothic Architecture (1747), a publication that was available in America by the end of the 18th century [See Fig. 9].

Arcades were also associated with public gardens. For example, Columbia Garden in New York, which opened in 1810 under the ownership of Daniel Ensley, included two arcades that flanked and encircled the central tower that was used by performers, and they probably served as seating areas for outside entertainment [Fig. 5].[2]

—Anne L. Helmreich

Texts

Usages

- Anonymous, April 12, 1787, describing Harmony Hall, Charleston, SC (Columbian Herald)

- “Harmony Hall. THEATRICAL REPRESENTATIONS being prohibited by a late Act of the Legislature, Mr. Godwin, most respectfully acquaints his friends, and those Ladies and Gentlemen who have kindly patronized him, that his lease of the lot of land whereon the building called Harmony-Hall now stands, will not expire for some time; therefore, he is converting the house into an Assembly Room. . . ALSO, FOR CONCERTS. . . And Dancing. An excellent floor is to be laid over that part formerly called the Pit.—The side boxes will be turned to ARBOURS—the front boxes into an ARCADE—where the company may sit during the music, and enjoy the innocent, natural amusements of tea, cooling liquors, cold collation, &c.”

- Attmore, William, November 23, 1787, describing the Governor’s House, New Bern, NC (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “The palace is a building erected by the province before the Revolution—It is a large and elegant brick Edifice two Stories high, with two Wings for the offices, somewhat advanced in front towards the Road, these are also two Stories high but lower in height than the main Building, these Wings are connected with the principal Building by a circular arcade from each of the front Corners to the corner of the Wing.”

- Dwight, Timothy, 1796, describing the Hartford Statehouse, Hartford, CT (1821: 1:234)[3]

- “The State-House is fifty feet in width, fifty in height, and one hundred and thirty in length. . . From each front, finished with iron gates, projects an open arcade, sixteen feet wide, and forty long.”

- Latrobe, Benjamin Henry, July 19, 1796, describing Mount Vernon, plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (1977: 1:163)[4]

- “The general plan of the building is as at Mr. Man Pages at Mansfield near Fredericsburg, of the old School. . . The center is an old house to which a good dining room has been added at the North end, and a study &c. &c., at the South. The House is connected with the Kitchen offices by arcades.” [Fig. 6]

- Latrobe, Benjamin Henry, November 28, 1798, describing a prison in Richmond, VA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “The Ground floor contains the Kitchen and Bakehouse and an open Arcade, the use of which is to admit air into the Area of the building from the Westward, the Quarter from which the Summer winds most usually blow.”

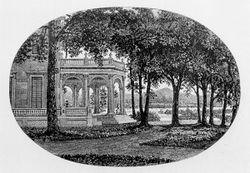

- Buckingham, James Silk, April 1840, describing the garden of Father George Rapp, Economy, PA (1842: 2:227)[5]

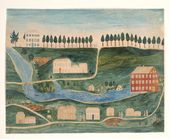

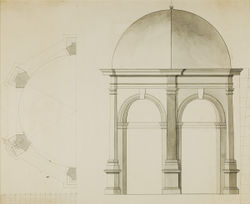

- “After a short introductory conversation, he invited us to accompany him to his garden, before the day closed in, and we readily attended him there. This covered about an acre and half of ground, and was neatly laid out in lawns, arbours, and flower-beds, with two prettily ornamented open octagonal arcades, each supporting a circular dome over a fountain.” [Fig. 7]

- Downing, A. J., October 1847, “A Visit to Montgomery Place,” describing Montgomery Place, the country home of Mrs. Edward (Louise) Livingston, Dutchess County, NY (Horticulturist 2: 155)[6]

- “Its ribbed roof is supported by a tasteful series of columns and arches, in the style of an Italian arcade. As it is on the north side of the dwelling, its position is always cool in summer; and this coolness is still farther increased by the abundant shade of tall old trees, whose heads cast a pleasant gloom, while their tall trunks allow the eye to feast on the rich landscape spread around it.” [Fig. 8]

Citations

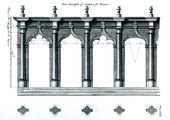

- Langley, Batty and Thomas, 1747, Gothic Architecture (1747: n.p)[7]

- “XXIX. Arcades for Piazzas, with the Geometrical Construction of their Curves.” [Fig. 9]

- Salmon, William, 1762, Palladio Londinensis (1762: n.p.)[8]

- “Arcade, a Range of Arches with open Places to walk, as that of Covent Garden, the Royal Exchange, &c.”

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828: 1:n.p.)[9]

- Tuthill, Louisa C. (Louisa Caroline), 1848, History of Architecture (1848; repr., 1988: 382)[10]

- “Arcade. A series of arched openings, with a roof or ceiling.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1850, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850; repr., 1968: 281, 354, 356)[11]

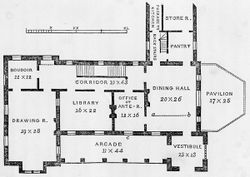

- “As a marked defect in this design. . . was the absence of all veranda, arcade, or covered walk—without which no country-house is tolerable in the United States, we have added a veranda in the angle between the library and drawing-room. . .

- “We see refined culture symbolized in the round-arch, with its continually recurring curves of beauty, in the spacious and elegant arcades, inviting to leisurely conversations, in all those outlines and details, suggestive of restrained and orderly action, as contrasted with the upward, aspiring, imaginative feeling indicated in the pointed or Gothic styles of architecture. . .

- “[Referring to Design XXXII.] Standing in the middle of the vestibule, the arcade extends to the drawing-room, affording a broad and airy promenade, nearly 60 feet long, sheltered from sun and rain.” [Fig. 10]

Images

Inscribed

Batty and Thomas Langley, “Four Examples of Arcades for Piazza’s,” in Batty Langley, Gothic Architecture (1747), pl. 29.

Anonymous, “Principal Floor” of a Southern Villa—Romanesque Style, in A. J. Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850), 353, fig. 169.

Associated

Anonymous, Plan of the garden pavilion at Economy, PA, c. 1830.

Anonymous (artist), A. Kollner (lithographer), “North West View of the Mansion of George Washington Mount Vernon,” in Franklin Knight, ed., Letters on Agriculture from His Excellency George Washington (1847), opp. p. 124.

Alexander Jackson Davis, “Montgomery Place,” in A. J. Downing, ed., Horticulturist 2, no. 4 (October 1847): pl. opp. 153.

Anonymous, “Southern Villa—Romanesque Style,” in A. J. Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850), pl. opp. 353, fig. 168.

Attributed

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Elevation of the South front of the President’s house, copied from the design as proposed to be altered in 1807, January 1817.

Robert Mills, Principal Front of the Lunatic Asylum Columbia South Carolina, c. 1820. Arcade is the range of arches in the center beneath the portico.

Anne-Marguerite Hyde de Neuville, Washington City, 1821.

Anthony St. John Baker, “View of the White House,” 1826, in Mémoires d’un voyageur qui se repose (1850).

Sarah Apthorp, A view of the Residence of the late President Adams at Quincy, Mass., 1837.

Notes

- ↑ Carl R. Lounsbury, ed., An Illustrated Glossary of Early Southern Architecture and Landscape (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994), 8, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Myers Garrett, “A History of Pleasure Gardens in New York City, 1700–1865” (PhD diss., New York University, 1978), 425, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Timothy Dwight, Travels; in New-England and New-York, 4 vols. (New Haven: The Author, 1821), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Benjamin Henry Latrobe, The Virginia Journals of Benjamin Henry Latrobe, 1795–1798, ed. Edward C. Carter II, 2 vols. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1977), view on Zotero.

- ↑ James Silk Buckingham, The Eastern and Western States of America, 3 vols. (London: Fisher, 1842), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alexander Jackson Downing, “A Visit to Montgomery Place,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 2, no. 4 (October 1847): 153–60, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Batty and Thomas Langley, Gothic Architecture, Improved by Rules and Proportions in Many Grand Designs (London: J. Millan, 1747), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Salmon, Palladio Londinensis, or The London Art of Building: In Three Parts. . . with Fifty-Four Copper Plates, to Which Is Annexed, The Builder’s Dictionary, ed. E. Hoppus, 6th ed. (London: Printed for C. Hitch et al., 1762), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Louisa C. Tuthill, History of Architecture, from the Earliest Times; Its Present Condition in Europe and the United States; with a Biography of Eminent Architects, and a Glossary of Architectural Terms, by Mrs. L. C. Tuthill (1848; repr., Philadelphia: Lindsay and Blakiston, 1988), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses; Including Designs for Cottages, Farm-Houses, and Villas (New York: D. Appleton, 1850; repr., New York: Da Capo, 1968), view on Zotero.