Promenade

History

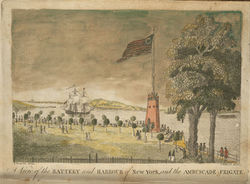

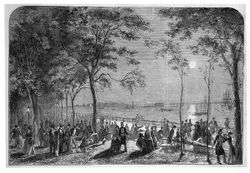

The term promenade, referring to an area of ground suitable for walking and riding, was generally applied to urban public spaces. It derived from the French promener (to walk), and was associated with walking as a leisure activity. As many observers noted, “barren” or primarily utilitarian spaces could be converted into promenades, often through the addition of such ornamentation as fences (to mark paths or walks) and trees, shrubs, and grass. Many places designated as promenades were also referred to by other terms that described either their accessibility to the public (such as public square or ground) or their association with entertainment (such as park or pleasure ground). Examples include the State House Yard in Philadelphia [Fig. 1], the Battery Park in New York [Fig. 2], Boston Common, and the national Mall in Washington, DC, all of which were also called promenades (see Common, Mall, Park, Public garden, and Square).

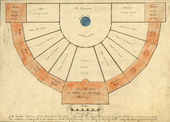

“Promenade” notably did not refer to the entire space encompassed by an urban public space. Instead, it designated a prominent walk or avenue within its boundaries. Shade trees, passage of sufficient breadth, and a resilient surface made these walks suitable for promenading. This form of social exercise was connected intimately with the rituals of fashionable display and decorous interaction. Respectable women were frequent patrons of promenades because of social conventions limiting where they could take exercise and seek entertainment. Note, for example, Fanny Kemble’s desperate search in 1839 for a promenade at one of her husband’s plantations at Butler Island, Georgia. This function required promenades to be not only suitably appointed but also sufficiently free of the exhibition of such vices as public drunkenness. In the case of New Orleans in 1801, it appears that drunkenness sabotaged efforts to convert public walks into promenades [Fig. 3]. This was the case along the levee and Place d’Armes (renamed Jackson Square).

Because promenades were associated with walking, the term was also applied to portions of buildings that provided ample space for walking, such as an arcade, gallery, piazza, porch, terrace, or veranda. As covered structures, the latter two were particularly well suited for patrons walking in inclement or hot weather. Outdoor promenades lined with shade trees offered a similar kind of buffer from the elements.

—Anne L. Helmreich

Texts

Usage

- Pintard, John, 1801, describing New Orleans, LA (quoted in Sterling, ed., 1951: 231)[1]

- “The only public walk is the levée, which is externally thronged with all sorts & conditions of people. It is far from an eligible promenade for the ladies—who are obliged to frequent it for exercise—It is about 8 feet wide, the slope towards the river presents all the shipping of the harbour with their usual concomitants of noisey [sic] drunken labourers & sailors.”

- Anonymous, 1815, describing in the Georgia Journal the improvements of the state capitol in Milledgeville, GA (quoted in Lounsbury 1994: 292)[2]

- “[Improvements included] the enclosure of the State-House square and avenues of trees planted in it, which in a few years will form an agreeable and beautiful prominade [sic].”

- Anonymous, 1817, describing Savannah, GA (quoted in Schwaab and Bull 1973: 144)[3]

- “Bay street is the principal street for business; it is parallel with the river, and being very wide, admits of a Mall in its centre, which is now completely shaded from the rays of the sun by the approximation of the boughs of two rows of those umbrageous trees [the Pride of India], which enclose a space convenient either as a promenade for walking, or an exchange for commercial transactions.”

- Anonymous, 1820, describing Memphis, TN (quoted in Schwaab and Bull 1973: 179)[3]

- “The streets run to the cardinal points. They are wide and spacious, and, together with a number of alleys, afford a free and abundant circulation of air. There are, besides, four public squares, in different parts of the town, and between the front lots and the river, is an ample vacant space, reserved as a promenade; all of which must contribute very much to the health and comfort of the place, as well as to its security and ornament.”

- Trollope, Frances Milton, 1830, describing New York, NY (1832: 2:158)[4]

- “The extreme point is fortified towards the sea by a battery, and forms an admirable point of defence; but in these piping days of peace, it is converted into a public promenade, and one more beautiful, I should suppose, no city could boast.” [Fig. 4]

- Anonymous, January 1, 1836, “Leaves from My Note Book” (Horticultural Register 2: 33)[5]

- “Apart from the beautiful scenery connected with these resorts [public walks in New York], or in themselves alone, they cannot compare with our fine Common, of which Bostonians deservedly pride themselves, and which at a little expense might be made one of the most splendid places of promenade in the country.” [Fig. 5]

- Anonymous, June 1, 1838, regarding a proposed botanic garden in Boston, MA (Horticultural Register 4: 239)[6]

- “A barren waste will soon be converted into a delightful promenade—a paradise in miniature.”

- Kemble, Fanny, January 1839, in a letter to Elizabeth Dwight Sedgwick, describing her husband’s plantations on Butler Island, GA (1984: 56)[7]

- “My walks are rather circumscribed, inasmuch as the dikes are the only promenades. On all sides of these lie either the marshy rice fields, the brimming river, or the swampy patches of yet unreclaimed forest.”

- Buckingham, James Silk, 1841, describing Philadelphia, PA (1841: 1:357)[8]

- “There are more public squares for promenades, and larger and better ones too in every respect, in Philadelphia than in New-York or Baltimore. They have been longer laid out, and their grass lawns, large trees, and fine gravel-walks render them most agreeable; but they are probably less valued here than they would be in almost any other city, from the circumstance of the streets being such agreeable places for walking, so perfectly level, so smoothly paved on the causeways at least, and so agreeably shaded with trees on each side.”

- Barber, John Warner, and Henry Howe, 1841, describing Hudson City, NY (1841: 116–17)[9]

- “Nearly all the streets intersect each other at right angles, except near the river, where they conform to the shape of the ground. The promenade at the western extremity, and fronting the principal street, commands a beautiful view of the river, the village of Athens opposite, the country beyond, and the towering Catskill mountains.”

- Hall, Abraham Oakley, 1846, describing the Place d’Armes (renamed Jackson Square), New Orleans, LA (quoted in Upton 1994: 283)[10]

- “A very neat railing, one or two respectable aged trees, a hundred or two blades of grass, a dilapidated fountain, a very naked flag-staff. . . It has a water view, and with a judicious expenditure of a few thousand dollars might be made an inviting promenade; it is now but a species of cheap lodging-house for arriving emigrants, drunken sailors, and lazy stevedores.’”

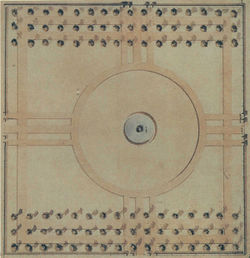

- Kirkbride, Thomas S., April 1848, describing the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane (American Journal of Insanity 4: 347–53)[11]

- “On the north and south side of the building are private yards, one hundred and seventeen feet wide, and extending two hundred feet from the return wings which form one of their sides. These yards are enclosed by a tight board fence seven and a half feet high, and are surrounded with a brick pavement, which affords a fine promenade at all seasons.

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1850, describing the State House Yard, Philadelphia, PA (1850: 332–33)[12]

- “856. Public Gardens. . .

- “Promenade at Philadelphia. There is a very pretty enclosure before the walnut tree entrance to the state-house, with good well-kept gravel walks, and many beautiful flowering trees. It is laid down in grass, not in turf; which indeed, Mrs. Trollope observes, ‘is a luxury she never saw in America.’”

- Anonymous, July 15, 1850, “Fashionable Promenades and Drives in the Metropolis,” describing New York, NY (New York Herald)

- “Our city is sadly deficient in fashionable promenades and drives, so that in the warm seasons the metropolis is scarcely endurable. There are no lungs to the island. It is made up entirely of veins and arteries. The Battery, Washington Parade Ground, the Park, Union Square, and a few small green spots in the arid desert of houses and streets, are all the places where fresh air can be obtained. These are only fit for pedestrians. We have nothing on the same scale of magnificence that marks European cities, such as Hyde Park and Kensington Gardens in London, the Champs Élysées of Paris, the Vauxhall of Berlin, the Corso of Milan, or the beautifully spacious drives of Berlin and Vienna.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1851, describing plans for improving the public grounds of Washington, DC (quoted in Washburn 1967: 54)[13]

- “1st: The President’s Park or Parade.

- “This comprises the open Ground directly south of the President’s House. Adopting suggestions made me at Washington I propose to keep the large area of this ground open, as a place for parade or military reviews, as well as public festivities or celebrations. A circular carriage drive 40 feet wide and nearly a mile long shaded by an avenue of Elms, surrounds the Parade, while a series of foot-paths, 10 feet wide, winding through thickets of trees and shrubs, forms the boundary to this park, and would make an agreeable shaded promenade for pedestrians.” [Fig. 6]

Citations

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826: 1028–29)[14]

- “7313. Public parks, or equestrian promenades, are valuable appendages to large cities. Extent and a free air are the principal requisites, and the roads should be arranged so as to produce few intersections; but at the same time so as carriages may make either the tour of the whole scene, or adopt a shorter tour at pleasure. . . .

- “7319. Public squares, of such magnitude as to admit of being laid out in ample walks, open and shady, are almost peculiar to Britain. The grand object is to get as extended a line of uninterrupted promenade as is possible within the given limits.”

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828: 2:n.p.)[15]

- “PROMENA’DE, n. [Fr. from promener; pro and mener, to lead.]

- “1. A walk for amusement or exercise.

- “2. A place for walking.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, August 1836, “Remarks on the Fitness of the different Styles of Architecture for the Construction of Country Residences, and on the Employment of Vases in Garden Scenery” (American Gardeners’ Magazine 2: 283)[16]

- “There can scarcely be a more appropriate, agreeable and beautiful residence for a citizen who retires to the country for the summer, than a modern Italian villa, with its ornamented chimneys, its broad verandah, forming a fine shady promenade, and its cool breezy apartments.”

- Johnson, George William, 1847, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening (1847: 584)[17]

- “[TERRACES. . .] Mr. Loudon is more practical on this subject , and observes. . .

- “‘Narrow terraces are entirely occupied as promenades, and may be either gravelled or paved; and different levels, when they exist, connected by inclined planes or flights of steps. . .’— Enc. Gard.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1850, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850; repr.,1968: 356)[18]

- “[Referring to Design XXXII.] Standing in the middle of the vestibule, the arcade extends to the drawing-room, affording a broad and airy promenade, nearly 60 feet long, sheltered from sun and rain.” [Fig. 8]

Images

Inscribed

Robert Mills, Plan of wings and courtyards, South Carolina Insane Asylum, 1821.

Anonymous, “Principal Floor” of a Southern Villa—Romanesque Style, in A. J. Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850), 353, fig. 169.

Associated

John Drayton, A View of the Battery and Harbour of New York, and the Ambuscade Frigate, 1794.

Nicolino Calyo, View of the Waterworks at Fairmount, 1835–36.

Thomas S. Sinclair, "Plan of the Pleasure Grounds and Farm of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane at Philadelphia," 1848 (detail). A promenade is visible at 10: “Gentlemen’s private yard”.

John Bachmann, Bird’s Eye View of Boston, c. 1850.

Anonymous, “Southern Villa—Romanesque Style,” in A. J. Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850), pl. opp. 353, fig. 168.

Attributed

Unknown, View of the Battery Looking North from the Churn, c.1812.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, “Plan of the public Square in the city of New Orleans, as proposed to be improved. . .” [detail], March 20, 1819.

Alexander Jackson Davis, Castle Garden, N. York, c. 1825–28.

Charles Willson Peale, Belfield Farm, c. 1816.

A. J. Downing, Plan Showing Proposed Method of Laying Out the Public Grounds at Washington, 1851.

W. Mason, “Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane,” c. 1841, in Thomas S. Kirkbride, Reports of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane: With a Sketch of its History, Buildings, and Organization (1851), frontispiece.

Notes

- ↑ David Lee Sterling, ed., “New Orleans, 1801: An Account by John Pintard,” Louisiana Historical Quarterly 34 (1951): 217–33, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Carl R. Lounsbury, ed., An Illustrated Glossary of Early Southern Architecture and Landscape (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Eugene L. Schwaab and Jacqueline Bull, Travels in the Old South (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1973), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Frances Milton Trollope, Domestic Manners of the Americans, 2 vols (London: Wittaker, Treacher & Co., 1832), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, “Leaves from My Note Book,” Horticultural Register, and Gardener’s Magazine 2 (January 1, 1836): 29–33, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, “Miscellaneous Matters,” Horticultural Register, and Gardener’s Magazine 4 (June 1, 1838): 238–39, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Frances Anne Kemble, Journal of a Residence on a Georgian Plantation in 1838–1839, ed. John A. Scott (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1984), view on Zotero.

- ↑ James Silk Buckingham, America, Historical, Statistic, and Descriptive, 2 vols. (New York: Harper, 1841), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Warner Barber and Henry Howe, Historical Collections of the State of New York. . . with Geographical Descriptions of Every Township in the State (New York: S. Tuttle, 1841), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Dell Upton, “The Master Street of the World, The Levee,” in Critical Perspectives on Public Space, eds. Çelik Zeynep, Diane Favro, and Richard Ingersoll (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994), 277–88, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas S. Kirkbride, “Description of the Pleasure Grounds and Farm of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, with Remarks,” American Journal of Insanity 4, no. 4 (April 1848): 347–54, view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, new ed. (London: Longman et al., 1850), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Wilcomb E. Washburn, “Vision of Life for the Mall,” AIA Journal 47 (1967): 52–59, view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, 4th ed. (London: Longman et al., 1826), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. Downing, “Remarks on the Fitness of the different Styles of Architecture for the Construction of Country Residences, and on the Employment of Vases in Garden Scenery,” American Gardeners’ Magazine, and Register of Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Horticulture and Rural Affairs 2, no. 8 (August 1836): 281–86, view on Zotero.

- ↑ George William Johnson, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening, ed. David Landreth (Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1847), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses; Including Designs for Cottages, Farm-Houses, and Villas (1850; repr., New York: Da Capo, 1968), view on Zotero.