Mall

See also: Common, Green, Lawn, Park, Public ground, Walk

History

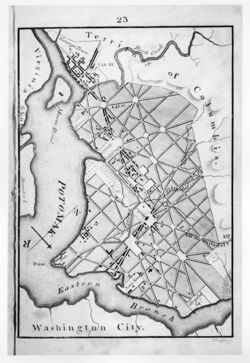

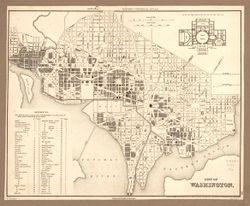

A public walk or promenade, the mall was part of the public appropriations of land in most major cities along the East Coast during the colonial and early Republic periods. The feature became such a constant part of the civic identity of American urban settlements that when the federal capital city was planned in the 1790s, a mall served as the ceremonial and geometrical center of the design [Figs. 1–3]. The choice of the term “mall” for the new public appropriation in Washington, DC, may have derived from the naming of the State House Yard in Philadelphia, which was also known as a mall. The association of the founding site of the new republic at Philadelphia with the new permanent capital city in Washington, DC, may be understood in this connection.

A mall referred not simply to open ground made available to the populace; but the term was also used to describe space that had been “improved” (see Common and Public ground). Most of the examples gathered for this study, both textual and visual, include references to improvement either by leveling or by the planting of an alley. Manasseh Cutler in 1787 described the mall in Middletown, Connecticut, as having been planted with buttonwoods. Images of the mall in Boston [Fig. 4] depict stylized trees demarcating it from the rest of the Boston Common, which until the 1830s was open ground used for assemblies and military exercises. The mall was used for more “civilized” activities, such as promenading. The national Mall in Washington, DC, was the preferred site for “gainful recreation”; as a result, it was the site of Benjamin Henry Latrobe’s proposed National University and, throughout the 19th century, a succession of botanic gardens and museums.[1]

The mall also served to link elements in the landscape. For example, Cutler described the mall at the State House Yard as an aisle leading from the street to the public building. Mall designs were generally linear, with an alley of trees demarcating the edges of the pathway or walk (see Promenade and Walk). A mall could also serve to enhance a view, as noted by Henry Wansey in 1794, in his description of the mall in Boston, where the canopy of the alley framed a view of the sea.

Records suggest that the specific plant material chosen for the planting of malls was frequently chosen for its cultural or political significance. After the American Revolution, Samuel Vaughan intended the State House Yard to be planted with trees from each of the states, presumably for symbolic purposes.[2] The buttonwood tree used for the mall in Middletown was a popular American export that was in high demand in England. In Savannah, Georgia, and Charleston, South Carolina [Fig. 5], the Pride of India, an exotic, non-native tree was selected to border the towns’ malls. It may not be a coincidence that from their founding, both of these southern port cities were important sites for the importation of and experimentation with non-native trees in the colonies.[3] If the selection of trees was also a statement of pride, then the civic expression was even more clearly associated with the creation and maintenance of a mall.

From Brunswick, Maine [Fig. 6], to Savannah, Georgia, malls were made to distinguish unimproved space and private land from that which was designed specifically for the use of the citizenry in an urban setting [Fig. 7]. Although it was a feature that appeared ubiquitously, it was not discussed in garden treatises. Perhaps, like the common or green, it was understood as a public and not individual construct, while the literature generally addressed the interests of the private gardener.

—Therese O’Malley

Texts

Usage

- Cutler, Manasseh, July 2, 1787, describing Middletown, CT (1987: 1:215–16)[4]

- “At the northern end of the city is a walk of two rows of buttonwood trees, from the front gate of a gentleman’s house down to a summer-house on the bank of the river, by far the most beautiful I ever saw. He permits the people of the city to improve it as a mall.”

- Cutler, Manasseh, July 13, 1787, describing State House Yard, Philadelphia (1987: 1:262–63)[4]

- “We passed through this broad aisle [of the State House] into the Mall. It is small, nearly square, and I believe does not contain more than one acre. As you enter the Mall through the State House, which is the only avenue to it, it appears to be nothing more than a large inner [[Court-yard to the State House]], ornamented with trees and walks. But here is a fine display of rural fancy and elegance. It was so lately laid out in its present form that it has not assumed that air of grandeur which time will give it. The trees are yet small, but most judiciously arranged. The artificial mounds of earth, and depressions, and small groves in the squares have a most delightful effect. The numerous walks are well graveled and rolled hard; they are all in a serpentine direction, which heightens the beauty, and affords constant variety. That painful sameness, commonly to be met with in garden-alleys, and others works of this kind, is happily avoided here, for there are no two parts of the Mall that are alike. Hogarth’s ‘Line of Beauty’ is here completely verified. The public are indebted to the fertile fancy and taste of Mr. Sam’l Vaughan, Esq., for the elegance of this plan. It was laid out and executed under his direction about three years ago. The Mall is at present nearly surrounded with buildings, which stand near to the board fence that incloses it, and the parts now vacant will, in a short time, be filled up.” [Fig. 8]

- Cutler, Manasseh, July 28, 1787, describing New York, NY (1987: 1:308)[4]

- “At the southern end of the city on the point of the Island, where North and East Rivers meet, is an old fort, now much out of repair. . . This fort is built on a prodigious mound of earth raised for that purpose, which makes the walls next the harbor near forty feet high, and seems to be well situated for commanding the entrance into both rivers. . . Around this fort is the Mall, where a vast concourse of gentlemen and ladies are constantly walking a little before sunset and in the evening. On the part of the Mall next the water, which is of considerable extent, is a broad and most beautiful glacis (built up with free-stone from the water), on which they walk. This is a cool and most delightful walk in an evening, having the sea open as far as Staten Island and Redhook, but in the day-time it greatly wants the shade of trees.”

- Enys, Lt. John, December 1, 1787, describing the mall in Boston, MA (quoted in Cometti, ed., 1976: 202)[5]

- “After Dinner we took a walk on the Mall as it is called which is a very excellent Gravel walk about half a Mile in Lenth with Trees on each side which is kept in very good order and is by far the best thing of the kind I have yet seen in America.”

- Wansey, Henry, May 11, 1794, describing the mall in Boston, MA (1794; repr., 1970: 60)[6]

- “On the south west side of the town, there is a pleasant promenade, called the Mall, adjoining to Boston Common, consisting of a long walk shaded by trees, about half the length of the Mall in St. James’s Park. At one end you have a fine view of the sea. The Common itself is a pleasant green field, with a gradual ascent from the sea shore, till it ends in Beacon Hill, a high point of land, commanding a very fine view of the country.”

- Dwight, Timothy, 1796, describing Newburyport, NH (1821: 1:439)[7]

- “A Mall has been begun on High-street; but on so small a scale, as ill to suit the purpose in view.”

- Bentley, William, September 12, 1801, describing Newburyport, MA (1962: 2:387)[8]

- “We then visited the beautiful mall which they have railed in High street above the pond. As it is now in high style & good order, it has very good effect.”

- Anonymous, 1817, describing Savannah, GA (quoted in Schwaab 1973: 144)[9]

- “Bay street is the principal street for business; it is parallel with the river, and being very wide, admits of a Mall in its centre, which is now completely shaded from the rays of the sun by the approximation of the boughs of two rows of those umbrageous trees [Pride of India], which enclose a space convenient either as a promenade for walking, or an exchange for commercial transactions.”

- Commissioner of Public Buildings, June 9, 1827, describing the Columbian Institute, Washington, DC (quoted in O’Malley 1989: 133)[10]

- “The new section of the Washington Canal was laid out along a line drawn through the middle of the Capitol and of the Mall. The pathway, canal and plantation in the garden do not coincide with this line, but diverge from it at an acute angle.”

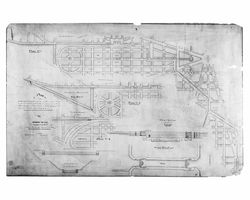

- Mills, Robert, February 23?, 1841, describing his design for the national Mall, Washington, DC (Scott, ed., 1990: n.p.)[11]

- “Agreeably to your requisition to prepare a plan of improvement to that part of the Mall lying between 7th and 12th Street West for a botanic garden. . . I have the honor to submit the following Report. . .

- “Drawing No. 1 presents a general plan of the entire Mall, including that annexed to the President’s house, with the particular improvement proposed of that part intended for the Institution and its objects.” [Fig. 9]

- Adams, Nehemiah, 1842, describing Boston Common, Boston, MA (1842: 12, 22–24, 43–45, 54)[12]

- “The elms and buttonwoods which adorn the Mall, are among the most interesting of the features of the Common. . .

- “The Common with its malls for hoops, and ball, and marbles, and wicker carriages. . . contributes as largely as any place can do to the formation of those youthful impressions which make childhood happy, and the remembrances of it pleasant. . .

- “The tents or booths around the Common on public days, are a study for a moralizer on human nature. . .

- “Early in the morning, the tables are piled with everything to tempt the appetite, and especially to draw the notice of the young. . . Many an urchin is in that crowd with two or three cents in his pocket, given him expressly to spend. . . He walks the whole length of the mall several times, uncertain upon which of the numerous objects of desire to bestow his little all. . .

- “It was resolved to continue the mall through the burial-ground, but it was foreseen that, in doing it, public accommodation would interfere with the private and sacred attachment of individuals to their ancestral tombs. . . The mall was continued through the burial-ground to make the entire circuit of the Common. . .

- “The brick side-walk around the Common is at present a more fashionable promenade than the beautiful mall with its arched avenue of trees. In the propensity of cultivated and fashionable life in our republican country to separate itself from the common and plebeian world, it is interesting to notice a different method of effecting its object from that in which an established nobility separates itself from the people. Nobility has its parks and terraced walks from which the public and cattle are excluded; but in this country the common people are peers of the realm, and the genteel, in order to maintain a separateness in their unavoidable union with them in certain enjoyments, give an artificial vogue to a place or thing which is obviously inferior to a thing of the same kind which the common people enjoy. This is probably the reason for the fact. . . that it is considered more genteel to promenade on the brick sidewalk, outside of the Common, than in the mall. . .

- “One of the next improvements in the Common we suspect will be a suitable supply of proper seats in the mall.”

Citations

- Johnson, Samuel, 1755, A Dictionary of the English Language (1755: 2:n.p.)[13]

- “MALL. n.s. [malleus, Lat. a hammer.] . . .

- “3. A walk where they formerly played with malls and balls.”

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828: 2:n.p.)[14]

- “MALL, n. mal. [Arm. mailh. Qu. from a play with mall and ball, or a beaten walk.]

- “A public walk; a level shaded walk. Allée d’arbres battue et bordée. Gregoire’s Arm. Dict.”

Images

Inscribed

Francis Dewing after John Bonner, A New Plan of ye Great Town of Boston in New England in America, 1743. The term “Mall” is indicated between the tree-lined alley under the word “Common,” at the left center of the image.

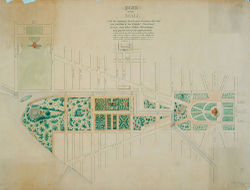

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Plan of the west end of the public appropriation in the city of Washington, called the Mall: as proposed to be arranged for the site of the university, 1816.

Anonymous, Map of the Columbian Institute's plot for a botanical garden on the Mall, 1820.

Robert Mills, Plan of the Washington Canal, 1831. “Mall” is inscribed in the lower left quadrant.

Robert Mills, Plan of the Mall, Washington, DC, 1841.

Associated

Pierre-Charles L'Enfant, Plan of the City intended for the Permanent Seat of the Government of the United States. . . , 1791.

Edward Weber, View of Washington City and Georgetown [detail], 1849.

Robert P. Smith, View of Washington, c. 1850.

Edward Sachse, View of Washington, 1852.

Attributed

Thomas Jefferson, Plan for the City of Washington, March 1791.

Notes

- ↑ Therese O’Malley, “‘A Public Museum of Trees’: Mid-Nineteenth Century Plans for the Mall,” in The Mall in Washington, 1791–1991, ed. Richard Longstreth (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Edward Riley, “The Independence Hall Group,” Historic Philadelphia: Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 43, part 1 (1953): 7–9, view on Zotero. Ultimately, one hundred elms were planted instead.

- ↑ Mark Catesby was active in Charlestown in introducing exotics from the Caribbean, the Old World, and also other parts of the colonies as early as the 1720s. The Trustees’ Garden in Savannah, for example, was established upon the founding of the city as a botanic garden where attempts were made to naturalize Old World plants and propagate native species.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 William Parker Cutler and Julia Perkins Cutler, eds., Life, Journals, and Correspondence of Rev. Manasseh Cutler, LL.D., 2 vols. (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1987), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Elizabeth Cometti, ed., The American Journals of Lt. John Enys (Syracuse, NY: Adirondack Museum and Syracuse University Press, 1976), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Henry Wansey, Henry Wansey and His American Journal, ed. David John Jeremy (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1970), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Timothy Dwight, Travels; in New-England and New-York, 4 vols. (New Haven: The Author, 1821), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Bentley, The Diary of William Bentley, D.D., Pastor of the East Church, Salem, Massachusetts (Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1962), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Eugene L. Schwaab and Jacqueline Bull, Travels in the Old South (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1973), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Therese O’Malley, “Art and Science in American Landscape Architecture: The National Mall, Washington, DC, 1791–1852” (PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1989), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Pamela Scott, ed., The Papers of Robert Mills (Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Resources, 1990), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Nehemiah Adams, Boston Common (Boston: William D. Ticknor and H. B. Williams, 1842), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (London: W. Strahan for J. and P. Knapton, 1755), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero.