Bowling green

(Boleing green, Bolling green, Boulingrin, Bowling-green)

See also: Green, Lawn

History

The term bowling green is derived from its frequent association with the turfed, circular space used for ball games popular in Europe and America. European garden treatises, such as A.-J. Dezallier d’Argenville’s Theory and Practice of Gardening (1712), noted that the term “bowling green” denoted several, interrelated meanings: a sunken, generally round, turfed lawn; a close-cropped playing field for bowls; and a recessed turfed area in the midst of a parterre or grove. In America before 1850, the term “bowling green” encompassed each of these three definitions, often in combination, and was applied to both public and private spaces. As a resolution by the New York Common Council in 1733 suggests, the bowling green’s ornamental and recreational functions often were inseparable. The term is complicated by the fact that lawn bowling took place on spaces other than bowling greens. For example, in 1611, Sir Thomas Dale disapproved of the bowlers’ language as they played in the streets of Jamestown, Virginia, and an 1826 engraving of the University of Virginia shows students bowling between the pavilions on the lawn, which was neither sunken nor circular in shape [Fig. 1].[1]

The term “bowling green” in Anglo-American culture is clearly allied to its British counterpart, but the history of bowling greens as a landscape feature in the two countries differed in large part because of the fundamentally different social structure and land-holding practices in England. For instance, in England bowling was legally restricted to private gardens by the government, which feared archery was being neglected. By the time of the Civil War in 1688 “there were few gentry gardens which did not include a bowling green.”[2]

In early America, bowling was not restricted in the same way. While images of public bowling greens are relatively rare in the colonial period, descriptions indicate that public bowling greens, such as those in Williamsburg, Virginia, Boston, and New York contributed to the beauty of the town or city and provided a venue for social gatherings and recreation [Fig. 2]. As early as the 1670s, tavern owners in New York provided bowls, ninepins, or skittles for their customers, resulting in the Common Council’s passage in 1676 of new Sabbath laws, which declared “all and Every Wine and Rum or Beare Sellas [beer sellers] who shall permitt any Person Upon the Sabbath day to Drinke or Game In their houses Gardens or Yards Shall for ye first offense forfeict five and Twenty Guildars.”[3] Bowling greens toward the end of the 18th century were commonly operated at taverns, hotels, and public pleasure grounds as part of the growing competition for public entertainment.[4] The Centre House Tavern at Centre Square in Philadelphia and Chatsworth Garden in Baltimore are two such examples. As the popularity of bowling declined in the early nineteenth century, public greens that had been used for sport often kept their names and became small enclosed parks, such as Bowling Green at the end of Broadway in New York [Fig. 3]. The flat, open space of a bowling green also made it ideal for other recreational purposes, such as a horse race held in Alexandria, Virginia, reported in 1790.

In private settings, as well, the bowling green combined ornament and recreation. The paucity of 17th- and early 18th-century examples of bowling greens on private estates suggests that only those colonists who had substantial resources, such as William Byrd II and William Middleton, devoted the labor and space necessary to construct the turfed greens. It has been argued that genteel sports—such as lawn bowling, fencing, and riding—in developing their particular rules, modes of performance, and conventions, helped to define the colonial social structure.[5] In the second half of the 18th century, the practice of constructing bowling greens on estates of the economic and political elite grew as more gentry had the luxury of expending their efforts on ornamental and recreational landscape features. Examples include Thomas Jefferson's Poplar Forest in Bedford County, Virginia, Charles and Margaret Tilghman Carroll’s plantation, Mount Clare, in Baltimore, and George Washington's Mount Vernon. The praise garnered by these landscape features suggests that bowling greens carried with them connotations of leisure and sophistication and that they were visible markers of their owners’ status.

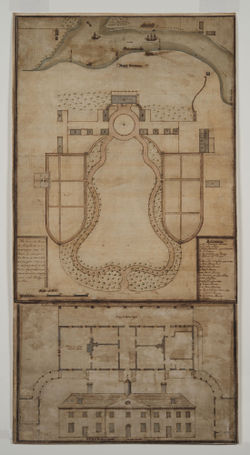

According to visual and textual evidence, bowling greens varied in their physical form and placement within the garden. One example of a bowling green depicted as a recessed area can be found in Charles Varlé’s design for the town of Bath, in which he included a bowling green within a parterre at “H” [Fig. 4]. Eliza Lucas Pinckney in 1743 also described the bowling green as sunk below the level of the rest of the garden. Private bowling greens could be circular, as at Mount Vernon [Fig. 5], or rectangular, as at the estate of John Penn in Philadelphia [Fig. 6], and they were generally near the house. Their flat, green swath of turf made an attractive foreground for a house and was related to the feature of lawns. In addition, the bowling green [Fig. 7] provided an excellent viewing platform from which to gaze over a prospect. In fact, by the second half of the 18th century, the term had entered the language of landscape description at a metaphorical level, when P. Campbell in 1793 referred to an area that was “flat as a bowling green.”

—Elizabeth Kryder-Reid

Texts

Usage

- Sanford, Robert, July 1666, describing a Native American settlement near Port Royal, SC (quoted in Salley, ed., 1911: 100)[6]

- “Found as to the forme of building in every respect like that of Eddistowe, with a plaine place before the great round house for their bowling recreation, att th’ end of which stood a faire wood-den Crosse of the Spaniards ereccon.”

- Byrd, William, II, April 26, 1720 and May 4–5, 1721, describing the bowling green in Williamsburg, VA (Wright and Tinling, eds., 1958: 399, 525–26)[7]

- “After dinner we walked to the bowling green where I gave the woman a pistole to encourage the green. . .

- “Then we walked to the bowling green and from thence to Colonel Bassett’s. . .

- “After dinner we walked to the bowling green where I lost five shillings.”

- Byrd, William, II, March 16, 1721, describing Westover, seat of William Byrd II, on the James River, VA (Wright and Tinling, eds., 1958: 507)[7]

- “This day we began to turf the bowling green.”

- Common Council, March 12, 1733, describing New York, NY (quoted in Hedrick 1988: 64)[8]

- “Resolved that this Corporation will lease a piece of Land lying at the lower end of Broadway fronting to the Fort, to some of the inhabitants of the said Broadway in order to be inclosed. . . to make a Bowling Green thereon, for the Beauty and Ornament of said Street as Well as for the Recreation & Delight of the Inhabitants of This City.”

- Pinckney, Eliza Lucas, c. May 1743, describing Crowfield, plantation of William Middleton, vicinity of Charleston, SC (1972: 61)[9]

- “Opposite on the left hand is a large square boleing green sunk a little below the level of the rest of the garden with a walk quite round composed of a double row of fine large flowering Laurel and Catulpas which form both shade and beauty.”

- Anonymous, September 12, 1754, describing a property for sale in Charleston, SC (South Carolina Gazette)

- “TO BE SOLD by the Subscriber, the House up the Path wherein he now liveth, together with all the Out houses, Bowling Green, Gardens, and other Land thereto belonging.”

- Fisher, Daniel, May 25, 1755, describing Centre House (Tavern), Philadelphia (quoted in Pecquet du Bellet 1907: 2:802)[10]

- “In coming home, I went into a Tavern called the ‘Centre House,’ as being seated in the very midst of the original Plan of the first intended City. . . Here is a Bowling Green.”

- Ecuyer, Capt. Simeon, April 1764, describing Fort Pitt, Pittsburgh (quoted in Stotz 1970: 14)[11]

- “. . . the deer park, the little garden, and the bowling green, I am just now making into one garden, it will be extreamly [sic] pretty and very useful to this garrison, the King’s garden will be put in proper order.”

- Ambler, Mary M., 1770, describing Mount Clare, plantation of Charles and Margaret Tilghman Carroll, Baltimore, MD (1937: 166)[12]

- “. . . took a great deal of Pleasure in looking at the Bowling Green. . . the House where this Gentn & his Lady reside in the Sumer stands upon a very High Hill & has a fine Veiw [sic] of Petapsico River You Step out of the Door into the Bowlg Green from which the Garden Falls & when You stand on the Top of it there is such an Uniformity of Each side as the whole Plantn seems to be laid out like a Garden.”

- Carter, Robert, 1770 and 1772, describing the garden at Sabine Hall, estate of Landon Carter, Richmond County, VA (quoted in Martin 1991: 116)[13]

- [March 1770] “I had my Ewes first on my bowling green yesterday and then on the hill sides. . .

- [April 25, 1772] “Talbot set to work yesterday to shave the bowling green, he seems to do it well, but he is very slow.”

- Carroll, Charles (of Annapolis), 1775, describing Carroll Garden, Annapolis, MD (Maryland Historical Society, A. E. Carroll Papers)

- “Examine the Gardiner strictly as to. . . Whether he is an expert at levelling, making grass plots & Bowling Greens, Slopes, & turfing them well.”

- Braxton, Col. George, 1776–81, describing his garden in King and Queen County, VA (quoted in Horner 1898: 147–48)[14]

- “I agreed wth Alexander Oliver Gardener to make a Courtyard before my Door according to Art; and after the best manner I shall think proper, that is likewise to finish my falling Garden with a Bolling Green.”

- Washington, George, 1785, describing Mount Vernon, plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (Jackson and Twohig, eds., 1978: 4:199, 215)[15]

- [September 30] “Began again to Smooth the Face of the Lawn, or Bolling Green on the West front of my House—what I had done before the Rains, proving abortive. . .

- [October 28] “Finished levelling and Sowing the lawn in front of the Ho[use] intended for a Bolling Green—as far as the Garden Houses.” [Fig. 8]

- Anonymous, September 20, 1790, describing in the Virginia Gazette and Alexander Advertiser a bowling green in Alexandria, VA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “THE VIRGINIA JOCKEY-CLUB RACES will commence at the Bowling Green on the second Tuesday in October next, and will continue three days.”

- Anonymous, June 25, 1792, describing a property for sale in New York, NY (New York Diary or Loudon’s Register)

- “A bowling green is in front, and stables, wood house and other necessary offices in the rear of the house.”

- Drayton, John, 1793, describing the Battery, New York, NY (quoted in Deák 1988: 1:130)[16]

- “The flag staff rises from the midst of a stone tower, and is decorated on the top with a golden ball: and the back part of the ground is laid out in smaller walks, terraces, and a bowling green.— Immediately behind this, and overlooking it, is the government house; built at the expence of the state.”

- Campbell, P., 1793, describing the journey from Frederick Town to Quebec (1793: 89)[17]

- “In this way [by canoe] we kept on our course, and on the first day passed many spacious fertile islands, averaged at about 100 acres extent each, flat as a bowling green, mostly covered with the loftiest hard timber imaginable, delightfully situated, the soil deep and of the richest quality, the country closely inhabited.”

- Niemcewicz, Julian Ursyn, June 1798, describing Mount Vernon, plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (quoted in Martin 1991: 140)[13]

- “Two bowling greens, a circular one near the house, the other very large and irregular, form the courtyard in front of the house. All kinds of trees, bushes, flowering plants, ornament the two sides of the court. . . The path which runs all around the bowling green is planted with a thousands kind[s] of trees, plants and bushes; crowning them are two immense Spanish chestnuts that Gl. Wash planted himself.”

- Martin, William Dickinson, May 15, 1805, describing the court house in Caroline County, VA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “Just at Sunrise we breakfasted at Caroline Court House, perhaps better known by the Bowling-Green, having travelled fifty miles the preceding night. This place is called the Bowling Green, from the extensiveness & evenness. . . of its plane, & high state of Cultivation. It was formerly the property of Mr. John Holmes, who has added so much to the stock of Horses in America, by his importation. It descended to his son on his death, & for many years has been well known in the racing world.”

- Hemings, J., 28 August 1825, describing Poplar Forest, property of Thomas Jefferson, Bedford County, VA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “The Area of the Triangle made by the Wash-House, Stable & School-House is perfectly levil, & designed for a bowling-Green, laid out in rectangular Walks which are paved with Brick, & covered over with burnt Oyster-Shells.”

- Lambert, John, 1816, describing the vicinity of Charleston, SC (1816: 2:231)[18]

- “The road was narrow, and nearly as level as a bowling-green; the soil varied in different places, but in general it was a light sandy earth, and free from stones.”

- Buckingham, James Silk, 1841, describing New York, NY (1841: 1:38–39)[19]

- “Of the public places for air and exercise with which the Continental cities of Europe are so abundantly and agreeably furnished, and which London, Bath, and some other of the larger cities of England contain, there is a marked deficiency in New-York. Except the Battery, which is agreeable only in summer—the Bowling Green is a confined space of 200 feet long by 150 broad; the Park, which is a comparatively small spot of land (about ten acres only) in the heart of the city, and quite a public thoroughfare; Hudson Square, the prettiest of the whole, but small, being only about four acres; and the open space within Washington Square, about nine acres, which is not yet furnished with gravel-walks or shady trees—there is no large place in the nature of a park, or public garden, or public walk, where persons of all classes may take air and exercise. This is a defect which, it is hoped, will ere long be remedied, as there is no country, perhaps, in which it would be more advantageous to the health and pleasure of the community than this to encourage, by every possible means, the use of air and exercise to a much greater extent than either is at present enjoyed.”

Citations

- Cotton, Charles, 1674, The Compleat Gamester (1674; repr., 1970: 39–41)[20]

- “BOWLING is a Game of Recreation, which if moderately used is very healthy for the body, and would be much more commendable than it is, were it not for those swarms of Rooks which so pester Bowling-Greens, Bares, and Bowling-Alleys where any such places are to be found, some making so small a spot of Ground yield them more Annually than fifty Acres of Land shall do elsewhere about the City, and this done, cunning, betting, crafty matching any basely playing booty.

- “In Bowling there is a great Art in chusing out his ground, and preventing the windings, hanging, and many turning advantages of the same, whether it be in open wide Places, as Bares, and Bowling-greens, or in close Bowling-Alleys. Where note that in Bowling the chusing of the Bowl is the greatest cunning. Flat Bowls are best for close Alley; round bypassed Bowls for open Grounds of Advantage, and Bowls round as a Ball for green Swarths that are plain and level. . .

- “The Character of a Bowling-Ally and Bowling-Green.

- “A Bowling-Green, or Bowling-Ally is a place where three things are thrown away besides Bowls, viz. Time, Money and Curses, at the last ten for one. The best sport in it, is the Gamesters, and he enjoyns it that looks on and betts nothing. . .

- “To give you the Moral of it, it is the Emblem of the World, or the Worlds Ambition, where most are short, over, wide or wrong bypassed, and some few justle in to the Mistress, Fortune! And here it is as in the Court, where the nearest are the most spighted, and all Bowls aim at the other.”

- Dezallier d’Argenville, Antoine-Joseph, The Theory and Practice of Gardening (1712: 61–62)[21]

- “THE Invention and Original of the Word Bowling-green, comes to us from England. Many Authors derive it from two English Words, namely, from Bowl, which signifies a round Body; and from Green, which denotes a Meadow, or Field of Grass; probably, because of the Figure in which it is sunk, which is commonly round, and cover’d with Grass. Others will have it, that the Word Bowling-green takes its Name from the large Green-plots, on which they are wont to play at Bowls in England, and for which purpose the English take care to keep their Grass very short, and extremely smooth and eaven.

- “A BOWLING-GREEN in France differs from all this. We mean no other by this Word, than certain hollow Sinkings and Slopes of Turf, which are practis’d, either in the Middle of very large Grass-works and Green-plots, or in a Grove, and sometimes in the Middle of a Parterre after the English Mode; which makes some People confound the Parterre à l’Angloise with the Boulingrin, believing them to be the same Thing, because the Invention of these two Compartiments comes from England, and they are both cover’d with Turf. However, in Gardens we ought to distinguish, and not to use the Word indifferently for all that is Grasswork, or improperly for other Parts of a Garden, as for large Flats of Grass that are in Groves, unless they are sunk hollow, for ’tis nothing but the Sinking that makes it a Bowling-green, together with the Grass that covers it.”

- Johnson, Samuel, 1755, A Dictionary of the English Language (1755: 1:n.p.)[22]

- “Bo'wling-green. n.s. [from bowl and green.] A level piece of ground, kept smooth for bowlers.”

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828: 1:n.p.)[23]

- “BOWLING-GREEN, n. [bowl and green.]

- “A level piece of ground kept smooth for bowling.

- “2. In gardening, a parterre in a grove, laid with fine turf, with compartments of divers figures, with dwarf trees and other decorations. It may be used for bowling; but the French and Italians have such greens for ornament. Encyc.”

- Johnson, George William, 1847, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening (1847: 584)[24]

- “[TERRACES. . .] Mr. Loudon is more practical on this subject, and observes. . .

- “‘In some cases the terrace-walls may be so extended as to enclose ground sufficient for a level plot to be used as a bowling green. These are generally connected with one of the living-rooms, or the conservatory; and to the latter is frequently joined an aviary, and the entire range of botanic stoves.’—Enc. Gard.”

Images

Inscribed

William Burgis, Plan of Boston in New England, 1728. The bowling green at Mill Pond was centrally located for social gatherings and recreation.

John Nancarrow, “Plan of the Seat of John Penn jun’r: Esqr: in Blockley Township and County of Philadelphia,” c. 1785. Note the reference “d. The Bowling Green.”

Mutual Assurance Society, Richmond, Declaration for Assurance Book, vol. 26, policy no. 2049, Insurance policy drawings for Mount Vernon, March 13, 1803. The term “bolling green” is inscribed across the circular lawn in front of the house.

Charles Varlé, Project for the Improvement of the Square and the Town of Bath, 1809. The “bolling green, etc” is the lower quadrangle marked at “H.”

James Smillie after Charles Burton, “Bowling Green, New York,” in Bourne Views of New York (1831), plate 2d.

Anonymous, “Bowling Green Fountain,” in E. Porter Belden, New-York, Past, Present, and Future (1850), opp. p. 30.

Anonymous (artist), Nathaniel Currier (lithographer), View of the Great Conflagration at New York July 19th 1845, 1845. Note the reference in the title "View of the Great Conflagration at New York July 19th 1845. From the Bowling Green."

Associated

Samuel Vaughan, Plan of Mount Vernon, 1787.

Edward Savage, The West Front of Mount Vernon, c. 1787–92.

Anonymous, A View of Mount Vernon, c. 1790.

George Isham Parkyns, Mount Vernon, 1795.

Anonymous (artist), A. Kollner (lithographer), “North West View of the Mansion of George Washington Mount Vernon,” in Franklin Knight, ed., Letters on Agriculture from His Excellency George Washington (1847), opp. p. 124.

Attributed

Franz Xaver Habermann, “La destruction de la statue royale à Nouvelle Yorck,” 1776.

Anthony St. John Baker, Mount Airy, Virginia; northeast front, 1827, in Mémoires d’un voyageur qui se repose (1850), part IV, p. 520A.

Anthony St. John Baker, Mount Airy, Virginia; southwest front as viewed from the bowling green, 1827, in Mémoires d’un voyageur qui se repose (1850), part IV, p. 520B.

Anthony St. John Baker, “Back View of Mount Airy, Va.,” 1827, in Mémoires d’un voyageur qui se repose (1850), part IV, p. 520B.

Anthony St. John Baker, “Front View of Mount Airy, Virginia,” 1827, in Mémoires d’un voyageur qui se repose (1850), part IV, p. 520A.

Notes

- ↑ Ulrich Troubetzkoy, “Bowls and Skittles,” Virginia Cavalcade 9 (Spring 1960): 15, view on Zotero. The game of bowls required little equipment and was played by two or more participants. A small white earthenware ball called the jack was tossed toward the players, who rolled their unevenly weighted spherical bowls, trying to be the closest to the jack. Ninepins, or skittles, was played in an alley, either indoors or out. Pins, often made of bone, were lined up and players tried to tip them over with the bowl until the winner scored exactly thirty-one points.

- ↑ Tom Williamson, Polite Landscapes: Gardens and Society in Eighteenth-Century England (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995), 34, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Myers Garrett, “A History of Pleasure Gardens in New York City, 1700–1865” (PhD diss., New York University, 1978), 57, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Taverns also often included other entertainment facilities such as cockpits and rings for boxers. Nancy L. Struna, “Sport and the Awareness of Leisure,” in Of Consuming Interests: The Style of Life in the Eighteenth Century, ed. Cary Carson, Ronald Hoffman, and Peter J. Alberts (Charlottesville and London: University of Virginia Press, 1994), 409, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Nancy L. Struna, “The Formalizing of Sport and the Formation of an Elite: The Chesapeake Gentry, 1650–1720s,” Journal of Sport History 13 (Winter 1986): 212–34, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alexander Salley Jr., ed., Narratives of Early Carolina, 1650–1708 (New York: Scribners, 1911), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Louis B. Wright and Marion Tinling, eds., The Secret Diary of William Byrd of Westover, 1709–1712 (New York: Arno Press, 1972), view on Zotero.

- ↑ U. P. Hedrick, A History of Horticulture in America to 1860; with an Addendum of Books Published from 1861–1920 by Elisabeth Woodburn (Portland, OR: Timber Press, 1988), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Eliza Lucas Pinckney, The Letterbook of Eliza Lucas Pinckney, 1739–1762, ed. Elise Pinckney (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1972), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Louise Pecquet du Bellet, ed., Some Prominent Virginia Families, 4 vols. (Lynchburg, VA: J. P. Bell, 1907), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Morse Stotz, Point of Empire, Conflict at the Forks of the Ohio (Pittsburgh: Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania, 1970), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Mary M. Ambler, “Diary of M. Ambler, 1770,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 45 (April 1937), 152–70, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Peter Martin, The Pleasure Gardens of Virginia: From Jamestown to Jefferson (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Frederick Horner, The History of the Blair, Banister, and Braxton Families (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1898), view on Zotero.

- ↑ George Washington, The Diaries of George Washington, ed. Donald Jackson and Dorothy Twohig, 6 vols. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1978), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Gloria Gilda Deák, Picturing America, 1497–1899: Prints, Maps, and Drawings Bearing on the New World Discoveries and on the Development of the Territory That Is Now the United States, 2 vols. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1988), view on Zotero.

- ↑ P. Campbell, Travels in the Interior Inhabited Parts of North America, In the Years 1791 and 1792 (Edinburgh: Printed by J. Guthrie, 1793), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Lambert, Travels through Canada, and the United States of North America in the Years 1806, 1807, and 1808, 2 vols. (London: Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy, 1816), view on Zotero.

- ↑ James Silk Buckingham, America, Historical, Statistic, and Descriptive, 2 vols. (New York: Harper, 1841), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Cotton, The Compleat Gamester (1674; repr., Barre, MA: Imprint Society, 1970), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A.-J. (Antoine Joseph) Dézallier d’Argenville, The Theory and Practice of Gardening; Wherein Is Fully Handled All That Relates to Fine Gardens, . . . Containing Divers Plans, and General Dispositions of Gardens. . . , trans. John James (London: Geo. James, 1712), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language: In Which the Words Are Deduced from the Originals and Illustrated in the Different Significations by Examples from the Best Writers, 2 vols. (London: W. Strahan for J. and P. Knapton, 1755), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ George William Johnson, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening, ed. David Landreth (Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1847), view on Zotero.