Edging

History

In 18th- and 19th-century gardening practice, edging referred to materials placed along the outer margins of planted areas (such as beds or borders) or along circulation routes (such as walks or avenues). Edgings were composed predominantly of plants, such as boxwood (also called “box”). Edging could also be made of inert substances such as earthenware, stone, iron, or wood, as Charles Marshall indicated in 1799. The choice of live or inert materials often depended upon the site, intended function, and dimensions of the edging. Early 19th-century treatises indicated that plant edgings were used to mark the boundaries of flower beds and borders in order to distinguish dug ground from walks, and to shore up and stabilize the worked earth of the bed or border [Fig. 1].

At Monticello, recent archaeology has shown that Thomas Jefferson used “brick bats” (or pieces of brick placed flat, end to end) to mark the perimeters of a garden bed.[1] The use of such edging in beds was often dictated by the garden style. For example, according to A. J. Downing (1849), flower beds cut into the turf (as in the irregular garden or the English garden), did not require edgings, whereas flower gardens featuring beds separated by walkways (as in the French or embroidery garden), required edgings.

H. A. S. Dearborn (1832) when recommending planting arrangements at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts, argued that plant edgings should be regarded only as a means of outlining space and not as barriers. Therefore, he believed they should be kept fairly low so as not to obstruct passage or viewing. If an obstacle or barrier was required, then the use of what Downing called “durable” material was often appropriate. A painting of about 1765 illustrates such an edging [Fig. 2].

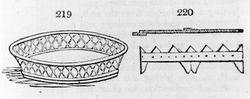

In An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826), J. C. Loudon recommended the use of basket edgings (such as dwarf fences made of basket willows) to keep small dogs and children out of flower beds. Basket edging fell within the category that Loudon defined as “moveable edgings”: edgings made of easily portable materials, such as earthenware, boards, and iron shoe tines stabilized in the ground.

As a result of the industrial revolution, decorative ironwork became cheaper and more accessible to the middle-class consumer in the early 19th century. Many of the gardens described by Loudon and Downing advocated the use of ornamental ironwork in outlining flower beds, particularly those set in lawns to emulate cut flowers in baskets or vases [Fig. 3]. Yet, artifice in edging was not necessarily dependent upon industrial technology. In 1816, G. (George) Gregory described edging flower beds with wood that was painted to resemble lead. Edgings, particularly those of woodwork or stone, also had the advantage of extending the lines and architectural style, or “character,” of the house into the garden, thus unifying house and garden, as Jane Loudon noted in 1845. Even edgings made of plants, especially boxwood, could carry architectural overtones. Treatise writers insisted frequently that box edgings be kept neat and trim, creating an architectonic effect.

Although box was repeatedly cited as the preeminent edging material—see, for example, J. C. Loudon (1826), Noah Webster (1828), Thomas Bridgeman (1832), and Robert Buist (1841)—other plants also were used, such as daisies and violets. Zebedee Cook Jr., in his 1830 address to the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, disputed the superiority of boxwood and claimed that grass was preferable for edging. M. A. W., writing in 1840 in the Magazine of Horticulture (a journal that, in general, touted box), also disparaged the nearly universal use of this plant. This writer believed that while box was useful for edging large garden features (such as avenues or broad walks), its scale overwhelmed small parterres and dooryard gardens. George William Johnson, in his 1847 definition, echoed this idea when he stated that box was appropriate for ornamental edgings, while herbs were more suited to kitchen or utilitarian gardens. Grass could be substituted for box, Johnson explained, but cautioned that it must be kept “in order.” Joseph Breck also cited thyme, hyssop, winter savory, and pinks as possible edging material, but concluded that “nothing . . . makes so neat and trim an edging as box.”

Given Jane Loudon's 1845 assertion that “[m]uch of the beauty of all gardens . . . depends on the neatness and high keeping of the edgings,” there are surprisingly few usage records of the term. In contrast, the numerous treatise citations instructing gardeners to employ edgings in the layout of their gardens underscore the importance that the feature held for gardeners.

—Anne L. Helmreich

Texts

Usage

- Dearborn, H. A. S., 1832, describing Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, MA (1833: 83)[2]

- “Edgings for such limited compartments as the Cemetery lots, must be formed of very humble plants, to be in keeping with their size and character; the box, violet, auricula, Burgundy rose, daisy, or some other plants, not more aspiring, can alone be used; and for the purpose of protecting the monument, on its circumscribed location, these would constitute no barrier.”

- Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), August 1841, “Notes made during a Visit to New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, &c.,” describing the residence of J. M. Bradhurst, Harlem, NY (Magazine of Horticulture 7: 323)[3]

- “The flower garden, containing about one eighth of an acre, in the form of a square, is laid out in small beds of various shapes, with box edgings. Each of the beds we found full of annuals and perennials, and green-house plants turned out of the pots into the ground.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, October 1847, describing the flower garden at Montgomery Place, country home of Mrs. Edward (Louise) Livingston, Dutchess County, NY (Horticulturist 2: 159)[4]

- “The walks are fancifully laid out, so as to form a tasteful whole; the beds are surrounded by low edgings of turf or box, and the whole looks like some rich oriental pattern or carpet of embroidery. In the centre of the garden stands a large vase of the Warwick pattern; others occupy the centres of parterres in the midst of its two main divisions, and at either end is a fanciful light summer-house, or pavilion, of Moresque character.” [Fig. 4]

Citations

- Miller, Philip, 1754, The Gardeners Dictionary (1754; repr., 1969: 459)[5]

- “EDGINGS. The best and most durable Plant for Edgings in a Garden is Box; which, if well planted, and rightly managed, will continue in Beauty for several Years: the best Season for planting this is either in Autumn, or very early in the Spring: for if you plant it late, and the Season should prove hot and dry, it will be very subject to miscarry, unless great Care is taken to supply it with Water. The best Sort for this Purpose is the Dwarf Dutch Box.

- “These Edgings are only planted upon the Sides of Borders next Walks, and not, as the Fashion was some Years ago, to plant the Edgings of Flower-beds, or the Edges of Fruit-borders, in the Middle of Gardens, unless they have a Gravel walk between them; which renders it proper to preserve the Walks clean, by keeping the Earth of the Borders from washing down in hard Rains.

- “It was also the Practice formerly, to plant Edgings of divers Sorts of aromatic Herbs, as Thyme, Savory, Hyssop, Lavender, Rue, &c. But these being subject to grow woody, so that they can’t be kept in due Compass, and in hard Winters being often killed in Patches, whereby the Edgings are rendered incomplete, they are now seldom used for this Purpose.

- “Some People make Edgings of Daisies, Thrift, Catchfly, and other flower Plants; but these also require to be transplanted every Year, in order to have them handsome; for they soon grow out of Form, and are subject also to decay in Patches; so that there is not any Plant which so completely answers the Design as Dwarf Box, which must be preferr’d to all others.”

- Marshall, Charles, 1799, An Introduction to the Knowledge and Practice of Gardening (1799: 1:55)[6]

- “Edgings of all sorts should be kept in good order and repair, as having a singular neat effect in the appearance of a garden. The dead edgings will sometimes, and the live edgings often want putting to rights; either cutting, clipping, or making up complete.”

- Gregory, G. (George), 1816, A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (1816: 1–2:n.p.)[7]

- “[vol. 1] EDGINGS, among gardeners, a series of small but durable plants, set round the edges or borders of flower-beds, &c.

- “The best and most durable plant for this use is box, which, if well planted, and rightly managed, will continue in strength and beauty for many years. The seasons for planting these are the autumn and very early in the spring; and the best species for this purpose is the dwarf Dutch box. The edgings of box are now only planted on the sides of borders next walls, and not, as was some time since the fashion, all round borders, or fruit-beds, in the middle of gardens, unless they have a gravel-walk between them, in which case it serves to keep the earth of the borders from washing down on the walks in hard rains, and fouling the gravel. Daisies, thrift, or sea-july-flowers, and chamomile, are also used by some for this purpose; but they grow out of form, and require yearly transplanting. . .

- “[vol. 2] GARDENING. . .

- “If edgings are to be made, in order to separate between the earth and gravel, especially if of stone, or wood, or box, they should be done first, and they will be a good rule to lay the box by. . .

- “Figured parterres have got out of fashion, as a taste for open and extensive gardening has prevailed; but when the beds are not too fanciful, but regular in their shapes, and chiefly at right angles, after the Chinese manner, an assemblage of all sorts of flowers, in a fancy spot of about 60 feet square, is a delightful home scource [sic] of pleasure, worthy of pursuit. There should be neat edgings of box to these beds, or rather of neat inch-boards, painted lead colour, to keep up the mould.”

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826: 296, 797)[8]

- “1500. Moveable edgings to borders, beds, or patches of flowers, are of different species.

- “1501. The basket-edging (fig. 219.) is a rim or fret of iron-wire, and sometimes of laths; formed, when small, in entire pieces, and when large, in segments. Its use is to enclose dug spots on lawns, so that when the flowers and shrubs cover the surface, they appear to grow from, or give some allusion to, a basket. These articles are also formed in cast-iron, and used as edgings to beds and plots, in plant-stoves and conservatories.

- “1502. The earthenware border. . . is composed of long narrow plates of common tile-clay, with the upper edge cut into such shapes as may be deemed ornamental. They form neat and permanent edgings to parterres; and are used more especially in Holland, as casings, or borderings to beds of florists’ flowers. [Fig. 5]

- “1503. Edgings of various sorts are formed of wire, basket-willows, laths, boards, plate-iron, and cast-iron; the last is much the best material. . .

- “6107. Edgings. In parterres where turf is not used as a ground or basis out of which to cut the beds and walks, the gravel of the latter is disparted from the dug ground of the former by edgings or rows of low-growing plants, as in the kitchen-garden. Various plants have been used for this purpose; but, as Neill observes, the best for extensive use is the dwarfish Dutch box, kept low and free from blanks. Abercrombie says, ‘Thrift is the neatest small evergreen next to box. In other parts, the daisy, pink, London-pride, primrose, violet, and periwinkle, may be employed as edgings. The strawberry, with the runners cut in close during summer, will also have a good effect; the wood-strawberry is suitable under the spreading shade of trees. Lastly, the limits between the gravel-walks and the dug-work may sometimes be marked by running verges of grass kept close and neat. Whatever edgings are employed, they should be formed previous to laying the gravel.’

- “6108. Basket-edgings. Small groups near the eye, and whether on grass or gravel, may be very neatly enclosed by a worked fence of basket-willows from six inches to a foot high. These wicker-work frames may be used with or without verdant edgings; they give a finished and enriched appearance to highly polished scenery; enhance the value of what is within, and help to keep off small dogs, children, &c.”

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828: 1:n.p.)[9]

- “EDG’ING, n. That which is added on the border, or which forms the edge; as lace, fringe, trimming, added to a garment for ornament. . .

- “2. A narrow lace.

- “3. In gardening, a row of small plants set along, the border of a flower-bed; as an edging of box. Encyc.”

- Cook, Zebedee, Jr., 1830, An Address, Pronounced Before the Massachusetts Horticultural Society (1830: 22–23)[10]

- “Grass edgings are preferable to those of box, their symmetry can be preserved with less care, and are less obnoxious to the charge of the treasonable practice of affording shelter and sustenance to myriads of insects which prey upon the delicious products of the vine and other rare fruit.”

- Bridgeman, Thomas, 1832, The Young Gardener’s Assistant (1832: 112, 122)[11]

- “Box and other edgings should be kept clear of weeds, and neatly trimmed every spring. . .

- “although box is superior to any thing else for edgings; yet in extensive gardens, dwarf plants of various kinds may be used for such purpose.”

- Sayers, Edward, 1838, The American Flower Garden Companion (1838: 15, 127–28)[12]

- “The beds [of a flower garden] should also be well proportioned, and not too much cut up into small figures, which when bordered with box edging, have the appearance of so many figures formed for the amusement of children more than for the purpose of growing flowers. There is also another great error sustained in this method, namely, the edging will retard the growth of the flowers by being close to them; for indeed there is nothing that so much exhausts the soil of nutriment, as box edging. . .

- “The flower garden attached to city residences,—when well managed,—embraces many useful features relative to health and pleasure. . .

- “The plan of the garden I recommend to be such as to give ease with variety; so as to accommodate various plants and shrubs; the walks to be of clean gravel, with an edging of box or neat dwarf plants—as the Thrift, Dwarf Iris, Moss pink, and such like.”

- W., M. A., February 1840, “On Flower Beds” (Magazine of Horticulture 6: 52–53)[13]

- “It is probably as difficult to fix upon the most suitable plant for the edging of a flower bed, as it is to determine the best shrub for a hedge around fields. For the borders of main avenues, or broad walks in grounds of considerable extent, box, as recommended, Vol. V., p. 350, is undoubtedly the best; but for small parterres, or the flower beds in a front door yard, it seems much less suitable. They can commonly be taken in at one glance of the eye, and notwithstanding all that has been said of the artificial or geometric style, it is the proper one for such places; for symmetry, or a perfect balance of corresponding parts, greatly strengthens the impression of such a scene, taken as a whole, or single mass of objects. The beds, therefore, will not only be small, but when there is the proper variety in the form of them, some, at least, must have quite acute angles. . .

- “And, upon the whole, perhaps no single plant whatever can fulfil all the requisite conditions, viz., a narrow and low line of perpetual green, diversified with flowers, to delight us with the contrast of their colors or the deliciousness of their perfume. A new charm would be added, if we could procure a successive variety of these; for what is likely to meet the eye several times every day, for months together, will soon lose its effects from monotony. We must, therefore, have recourse to a combination of several kinds, which will vegetate and flower in succession, without interfering with each other, upon the same ground.”

- Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), March 1840, “Some Remarks on the Formation of the Margins of Flower Beds on Grass Plots or Lawns” (Magazine of Horticulture 6: 84–85)[14]

- “We are glad to learn that our observations have been the means of drawing attention to the subject, and that they have, in some instances, induced amateurs to adopt the style of planting small grass plots, and forming upon them circular, or other shaped beds, for flowers. In front gardens to small suburban villas, nothing can be prettier than this plan of occupying the ground, and the method is, generally, to be much preferred to the old, and almost universally followed system, of forming gravelled walks, with board, grass, or box edgings, and dug borders. This is particularly so, when the object is to have a neat garden, and kept in order at the least expense.”

- Buist, Robert, 1841, The American Flower Garden Directory (1841: 31)[15]

- “BOX EDGINGS.

- “May be planted any time this month [March], or beginning of next, which in most seasons will be preferable. We will give a few simple directions how to accomplish the work. In the first place, dig over the ground deeply where the edging is intended to be planted, breaking the soil fine, and keeping it to a proper height, namely, about one inch higher than the side of the walk; but the taste of the operator will best decide, according to the situation.”

- Loudon, Jane, 1845, Gardening for Ladies (1845: 197)[16]

- “EDGINGS are lines of plants, generally evergreens, to separate walks from beds or borders. The plant in most universal use for this purpose in British gardens is the dwarf Box. . .

- “Edgings to beds and borders are also formed of other materials, such as lines of bricks, tiles, or slates, or of narrow strips of stone, or even of wood. In general, however, edgings of this kind have a meager appearance, especially in small gardens, though they have this advantage, that they do not harbour snails, slugs, or other vermin. In architectural flower-gardens, near a house, where the garden must necessarily partake of the character of the architecture of the building, stone or brick edgings are essential, and they should be formed of strips of curb-stone, bedded on stone or brickwork, so as never to sink. . .

- “Much of the beauty of all gardens, whether useful or ornamental, depends on the neatness and high keeping of the edgings; for whatever may be the state of the boundary fence, of the gravel, or pavement of the walks, and of the soil or plants of the borders, if the edgings have an uneven, ragged appearance, or if the plants be either too large or too small, the garden will be at once felt to be in bad keeping.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, April 1847, “Hints on Flower Gardens” (Horticulturist 1: 443)[17]

- “our own taste leads us to prefer the modern English style of laying out flower gardens upon a ground work of grass or turf, kept scrupulously short. Its advantage over a flower garden composed only of beds with a narrow edging and gravel walks, consists in the greater softness, freshness and verdure of the green turf, which serves as a setting to the flower beds, and heightens the brilliancy of the flowers themselves. Still, both these modes have their merits, and each is best adapted to certain situations, and harmonizes best with its appropriate scenery.”

- Johnson, George William, 1847, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening (1847: 208)[18]

- “EDGING. This for the kitchen-garden and all other places where neatness, not ornament, is the object, may consist of useful herbs, the strawberry &c. As an ornamental edging nothing can compare with the dwarf Box, especially in light soils. On heavy low lands it suffers during winter and may, perhaps, be totally destroyed; in such situations grass may be used, though it is troublesome to keep in order.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1849, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849; repr., 1991: 428–29)[19]

- “In almost all the different kinds of flowergardens, two methods of forming the beds are observed. One is, to cut the beds out of the green turf, which is ever afterwards kept well-mown or cut for the walks, and the edges pared; the other, to surround the beds with edgings of verdure, as box, etc., or some more durable material, as tiles, or cut stone, the walks between being covered with gravel. The turf is certainly the most agreeable for walking upon in the heat of summer, and the dry part of the day; while the gravelled flowergarden affords a dry footing at nearly all hours and seasons.”

- Breck, Joseph, 1851, The Flower-Garden (1851: 24)[20]

- “Thrift, if neatly planted, makes handsome edgings to borders or flower-beds. This may be planted as directed for box, slipping the old plants into small slips; setting the plants near enough to touch one another, forming a tolerably close row.

- “Thyme, hyssop, winter savory, and pinks are frequently used for edgings, but they are too prone to grow out of compass, and therefore not be recommended.

- “Many other plants are often used for edgings, but there is nothing that makes so neat and trim an edging as box.”

Images

Inscribed

J. C. Loudon, Moveable edgings: basket edging and the earthenware border, in An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826), 296, figs. 219 and 220.

Associated

J. C. Loudon, Plan of French parterre of embroidery, in An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826), 797, fig. 550.

Anonymous, “The Conservatory,” Montgomery Place, in A. J. Downing, ed., Horticulturist 2, no. 4 (October 1847): 159, fig. 28.

Anonymous, “Design for a Geometric Flower Garden,” in A. J. Downing, ed., Horticulturist 2, no. 12 (June 1848): 558, fig. 67.

Attributed

Anonymous, “The Seat of George Sheaff, Esq.” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849), pl. between 58 and 59, fig. 12.

Anonymous, “Mrs. Camac’s Residence,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849), pl. between 58 and 59, fig. 13.

Notes

- ↑ William M. Kelso, “Landscape Archaeology and Garden History Research: Success and Promise at Bacon’s Castle, Monticello, and Poplar Forest, Virginia,” in Garden History, Issues, Approaches, Methods, ed. John Dixon Hunt (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1992), 42, view on Zotero.

- ↑ H. A. S. (Henry Alexander Scammell) Dearborn, An Address Delivered before the Massachusetts Horticultural Society (Boston: J. T. Buckingham, 1833), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Mason Hovey, “Notes Made during a Visit to New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington, and Intermediate Places, from August 8th to the 23rd, 1841,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 7, no. 9 (September 1841): 321–27, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alexander Jackson Downing, "A Visit to Montgomery Place,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 2, no. 4 (October 1847): 153–60, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Philip Miller, The Gardeners Dictionary (1754; repr., New York: Verlag Von J. Cramer, 1969), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Marshall, An Introduction to the Knowledge and Practice of Gardening, 1st American ed., 2 vols. (Boston: Samuel Etheridge, 1799), view on Zotero.

- ↑ George Gregory, A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences, 1st American ed., 3 vols. (Philadelphia: Isaac Peirce, 1816), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, 4th ed. (London: Longman et al., 1826), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Zebedee Cook Jr., An Address, Pronounced before the Massachusetts Horticultural Society (Boston: Isaac R. Butts, 1830), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Bridgeman, The Young Gardener’s Assistant, 3rd ed. (New York: Geo. Robertson, 1832), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Edward Sayers, The American Flower Garden Companion, Adapted to the Northern States (Boston: Joseph Breck and Company, 1838), view on Zotero.

- ↑ M. A. W., “On Flower Beds,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 6, no. 2 (February 1840): 51–54, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Mason Hovey, “Some Remarks on the Formation of the Margins of Flower Beds on Grass Plots or Lawns,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 6, no. 3 (March 1840): 84–86, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Robert Buist, The American Flower Garden Directory, 2nd ed. (Philadelphia: Carey and Hart, 1841), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jane Loudon, Gardening for Ladies; and Companion to the Flower-Garden, ed. A. J. Downing (New York: Wiley & Putnam, 1845), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. Downing, “Hints on Flower Gardens,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 1, no. 10 (April 1847): 441–45, view on Zotero.

- ↑ George William Johnson, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening, ed. David Landreth (Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1847), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America, 4th ed. (1849; repr., Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Joseph Breck, The Flower-Garden, or Breck’s Book of Flowers (Boston: John P. Jewett, 1851), view on Zotero.