Conservatory

See also: Greenhouse, Hothouse, Nursery, Orangery

History

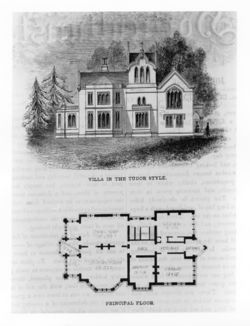

Numerous published definitions of conservatory indicate that this structure was intended for sheltering citrus trees and other tender plants during the winter. The building type seems to have been invented in the 16th century in England and named by John Evelyn in the 17th.[1] Although the conservatory was sometimes a free-standing building [Fig. 1], by the early 19th century it also was often attached to or formed part of the house, as noted in a plan in the June 1849 issue of the Horticulturist [Fig. 2]. Several garden writers, including C. M. Hovey and J. C. Loudon, attempted to distinguish the conservatory from the frequently synonymous term “greenhouse” by arguing that the two forms were fundamentally different. In a conservatory, plants were placed in “free soil” in beds or borders, whereas in the greenhouse they were placed in pots or tubs. In spite of this distinction, the terms seem to have been used synonymously in both American and British garden traditions (see Greenhouse, Hothouse, and Orangery).

Citations of the terms affirm their interchangeable nature. These references suggest no regional or chronological preference for one term over the other. If there was any nuance or difference in their usage, it was in references to a fine house or structure with architectural pretensions. In these cases, the term “conservatory” seems to have been preferred over that of “greenhouse,” which carried a less architectural and more utilitarian connotation. In his journal, the Horticulturist, A. J. Downing offered many plans for villas and country houses with conservatories. It is interesting to note that in his presentation of house plans, the textual description of some examples used the term “conservatory.” Downing’s plans, however, were inscribed with the word “greenhouse.” In another example, Downing was quite specific about the distinction between the conservatory and common greenhouse, saying that the latter served to supply the former with plants only as they came into “perfection.” The result was that the conservatory was always filled with flowers at the peak of bloom. This display of perennial blooms also led to the alternate name for the conservatory: winter garden. As collections became specialized, more specific terminology was used to describe the conservatory, such as pinery, grapery, or peachery.

In America, the term “conservatory” was applied to a variety of structures including large free-standing buildings, sometimes as long as eighty feet. The term was used also to describe modest spaces of eight to ten feet square (which sometimes were called “plant cabinets”), connected to a main house.[2] Although most descriptions record structures that were rectilinear in plan and longer than they were wide, centrally planned conservatories were also constructed. The architectural style of these buildings usually was matched to that of the houses with which they were associated. For example, Louisa C. (Louisa Caroline) Tuthill in her book History of Architecture from the Earliest Times (1848) singled out for praise a large conservatory with a variety of Gothic windows adorning an Elizabethan villa in New Haven.

The success of the conservatory depended upon the efficiency of its heating and ventilation systems. The structure might be as simple as a building with large south-facing windows and a glass roof (often removable) to maximize vertical sunlight. Some conservatories were heated by smoke flues or indoor enclosed stoves.[3] Another method of heating, mentioned by Hovey (1837), was to run hot-water pipes under raised walkways within the structure or along one interior wall.

Loudon brought about a major technical revolution in horticultural architecture in 1812 when he suggested using cast iron and copper for a conservatory’s frames and sashes instead of the traditional structural material of wood. With metals, it became possible to build curving glass-and-iron structures that would last longer, require less mass than wood, and admit more light.[4]

The conservatory was often positioned prominently within the garden because it represented the wealth and erudition of its owner. As John Abercrombie (1817) instructed, it was placed in a “conspicuous part of the Pleasure ground, contiguous to” the house. Since the conservatory was built for the collection of exotics (plants that could not survive without the protection of the glass house), a certain aura of luxury or erudition was associated with the building.

When attached to the house, the conservatory often acted as a transitional space between the architecture of the house and the garden or landscape. Hovey (1841) mentioned two examples where the conservatory could be opened by removing glass slats in the warm weather, giving the effect of a piazza adjoining the house.

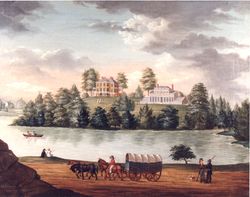

In the early republic, several of the most important botanical collections boasted large conservatories. Those at Lemon Hill in Philadelphia, dating from the late 18th century, were famous and often-illustrated landmarks [Fig. 3]. Elgin Botanic Garden in New York, founded in 1801 in association with the medical school of Columbia College, was represented in prints and paintings by its conservatory [Fig. 4]. The penchant for large private conservatories continued into the mid-19th century, illustrated by the conservatory designed in 1839 by Frederick Catherwood at Montgomery Place [Fig. 5].

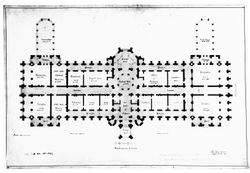

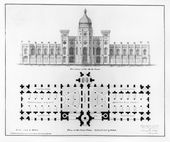

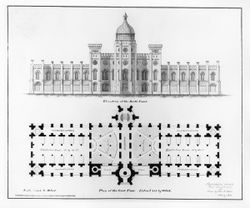

As the botanic garden became a part of public gardens and parks, its conservatories became popular places for socializing and spending leisure time in many towns and cities throughout America. As Dr. David Hosack said regarding conservatories in 1824, “[E]very such edifice, in a place of great public resort, will . . . have its influence in forming and directing the general taste of the country. The novelty of beautiful and curious exotics provided entertainment and rational amusement.” When architect Robert Mills proposed a building for the National Institute in Washington, DC, in 1841, he presented a Gothic revival museum with four conservatories, flanking the front and rear entrances [Fig. 6]. John Notman’s 1846 design for the Smithsonian Institution [Fig. 7] also featured both projecting conservatory and greenhouse, mirror images of one another.

During the 1830s and 1840s, the increasing appearance of conservatories in America reflected the general fashion for horticultural pursuits among the middle classes. It paralleled the development of commercial nurseries and popular horticultural literature promulgated by writers such as Hovey, Jane Loudon, and Downing, who encouraged the collection of plants in the home. The fashion for amateur gardening, the availability of many new plants, and the possibility of less expensive construction encouraged the addition of small domestic conservatories, a trend that reached a peak in the Victorian era.

—Therese O’Malley

Texts

Usage

- Hosack, David, 1806, describing Elgin Botanic Garden, New York, NY (1806: 3–4)[5]

- “In the year 1801 I purchased, of the Corporation of the city of New-York, twenty acres of ground; the greater part of which is now in cultivation. Since that time, a Conservatory, for the more hardy green-house plants, has been built.”

- Drayton, Charles, November 2, 1806, describing The Woodlands, seat of William Hamilton, near Philadelphia, PA (1806: 55—57)[6]

- “One is led into the garden from the portico, to the east or lefthand. or from the park, by a small gate contiguous to the house, traversing this walk, one sees many beauties of the landscape—also a fine statue, symbol of Winter, & age,—& a spacious Conservatory about 200 yards to the West of the Mansion.

- “The Conservatory consists of a green house, & 2 hot houses—one being at each end of it. The green house may be about 50 feet long. The front only is glazed. Scaffolds are erected, one higher than another, on which the plants in pots or tubs are placed—so that it is representing the declivity of a mountain. At each end are step-ladders for the purpose of going on each stage to water the plants—& to a walk at the back-wall. On the floor a walk of 5 or 6 feet extends along the glazed wall & at each end a door opens into an Hot house—so that a long walk extends in one line along the stove walls of the houses & the glazed wall of the green house.

- “The Hot houses, they may extend in front, I suppose, 40 feet each. They have a wall heated by flues—& 3 glazed walls & a glazed roof each. In the center, a frame of wood is raised about 2 1/2 feet high, & occupying the whole area except leaving a passage along by the walls. In the flue wall, or adjoining, is a cistern for tropic aquatic plants. Within the frame, is composed a hot bed; into which the pots & tubs with plants, are plunged. This Conservatory is said to be equal to any in Europe. It contains between 7 & 8000 plants. To this, the Professor of botany is permitted to resort, with his Pupils occasionally.

- “As the position of many plants require external exposure in the Summer season that also is contrived with much ingenuity & beauty.

- “There are 2 large oval grass plats in front of the Conservatory—& 2 behind. Holes are nicely made in these, to receive the pots & tubs with their plants, even to their rims. The tallest are placed in the centre, & decreasing to the verge. Thus they represent a miniature hill clothed with choice vegetation.”

- Newton, Joseph, Arthur Smith, John E. West, and Timothy B. Crane, 1810, describing the Elgin Botanic Garden, New York, NY (quoted in Hosack 1811: 45)[7]

- “Estimate of the Buildings at the Botanic Garden.

- “We, the subscribers, builders, and residents of the city of New-York, at the request of doctor David Hosack, have valued the improvements on his land, near the four mile stone, called the botanic garden, to wit: the hot bed frames, the conservatory or green house, and its appendages, the dwelling house, the hot houses and their back buildings, the lodges, the gates and the fences around the land, including the wells, at the sum of twenty-nine thousand three hundred dollars.” [Fig. 8]

- Waln, Robert, Jr., 1825, describing the Friends Asylum for the Insane, near Frankford, PA (1825: 12)[8]

- “A great variety of beautiful shrubs and flowers, mingle their rich and various tints, and shed around a delicious fragrance in this miniature conservatory of the beauties of nature.”

- Committee of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1830, describing Lemon Hill, estate of Henry Pratt, Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Boyd 1929: 432)[9]

- “The treasures contained in the hot and green houses are numerous. Besides a very fine collection of Orange, Lemon, Lime, Citron, Shaddock, Bergamot, Pomegranate and Fig trees in excellent condition and full of fruit, we notice with admiration the many thousand of exotics to which Mr. Pratt is annually adding. The most conspicuous among these, are the tea tree; the coffee tree—loaded with fruit; the sugar cane; the pepper tree; Banana, Plantain, Guva, Cherimona, Ficus, Mango, the Cacti in great splendour, some 14 feet high, and a gigantic Euphorbia Trigonia—19 years old, and 13 feet high. The green houses are 220 feet long by 16 broad; exhibiting the finest range of glass for the preservation of plants, on this continent. [See Fig. 4]

- “Colonel Perkins, near Boston, has it is true, a grapery and peach Espalier, protected by 330 feet of glass, yet as there are neither flues not foreign plants in them, they cannot properly be called green houses, whereas Mr. Pratt’s are furnished with the rarest productions of every clime, so that the committee place the conservatory of Lemon Hill at the very head of all similar establishments in this country.”

- Martineau, Harriet, 1834, describing Hyde Park, seat of David Hosack, on the Hudson River, NY (1838: 1:54)[10]

- “The conservatory is remarkable for America; and the flower-garden all that it can be made under present circumstances, but the neighbouring country people have no idea of a gentleman’s pleasure in his garden, and of respecting it.”

- Martineau, Harriet, 1835, describing Mount Vernon, plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (1838: 1:187)[10]

- “The conservatories were almost in ruins, scarcely a single pane of glass being unbroken; and the house looked as if it had not been painted on the outside for years.”

- Breck, Joseph, February 1, 1836, describing Bellmont Place, residence of John Perkins Cushing, Watertown, MA (Horticultural Register 2: 43–44)[11]

- “The garden is a square, level plot, bounded on the north side by the conservatories, which, if we are not mistaken, are four hundred feet in length. On the east and west are high, substantial brick walls, to which are trained a choice collection of fruit trees imported the last season, already formed for the purpose, some of which are protected by glass. The southern wall is very ornamental and substantial, and so low that the whole area and houses may be seen at a single glance outside the wall.”

- B., J., October 1, 1836, describing the garden of M. P. Sawyer, Portland, ME (Horticultural Register 2: 380–81)[12]

- “The garden of M. P. Sawyer, Esq. contains the only green-house of any note in the city or vicinity. This we visited, and found Mr Milne, who has charge of it, a man well skilled in his profession, and an ardent admirer of flowers. There are two houses upon it—The first a cold house for peaches and grapes, fiftythree feet long. The trees and vines were planted in it about the 20th June, 1835. The peach and some other trees are trained to the wall in a fine manner, and will probably produce fruit another season. . .

- “The other building is a common green-house or conservatory, fifty feet long, devoted in part to grapes.”

- Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), March 1837, describing the residence of N. I. Becar, New York, NY (Magazine of Horticulture 3: 162–63, 164–65)[13]

- “Attached to the garden of Mr. Becar is one of the finest conservatories I have ever seen. Indeed this, and that of Mr. Perry’s, in the same street, and but a short distance from Mr. Becar’s, taken together, may be considered as two of the best specimens of plant houses, in their peculiar style, that have ever been erected in the country. . .

- “This structure is not attached to the house, as is Mr. Perry’s, the situation of the garden not allowing of this; the distance is however, but a few steps, and it is thus easily accessible to the family at any season of the year. The length of the conservatory is upwards of fifty feet, and its width about fifteen. It fronts the garden, from which it is entered in the centre, and also at the end; the former entrance not being made use of during the mid-winter. The conservatory is built with a span roof, but is glazed only on the sides, the back being a solid brick wall. The situation of the garden being low, and the adjacent ground in the rear of the conservatory very high, it was found necessary to have it constructed in this manner; the back wall thus forms an excellent place for training up various kinds of runners and creepers, and when covered with them, will present a beautiful display of foliage and blossoms. . .

- “The interior of the house is constructed with a narrow border around the sides and ends, and an oblong bed in the centre; in the latter is planted out a great variety of choice plants, embracing several elegant and well grown specimens. The walk between this and the border, all round, is paved with marble; at each end of the large bed, is a beautiful marble vase, in which were growing vigorously, and running over the edges, that brilliant little gem, the Verbèna chamaedrifòlia. . .

- “The conservatory is warmed by a hot water apparatus, constructed by Mr. Anderson, an engineer, of Brooklyn. It is neat in its appearance, (the pipes being made of cast iron and bronzed;) but we do not admire the pipes running above the borders. In our opinion there is no method so neat, and at the same time equally as well adapted for heat in all kinds of horticultural structures, as that of running the hot water pipes under the walks, and allowing the heat to rise through a cast iron grating, or wooden trellis work.

- “Residence of ___ Perry, Esq.— . . . The conservatory here is heated on the same system as Mr. Becar’s, and the whole apparatus is precisely like his. The length and width of Mr. Perry’s conservatory is about the same as that of Mr. Becar’s; and the only superiority it possesses over his, is the facility with which it is entered from the parlor; adjoining immediately to the house, it is accessible at any moment during the day or evening. We noticed that elegant lamps were suspended in different parts of the conservatory; these, on many occasions, are lighted, and an evening promenade, much more extensive than most city gardens afford even in the summer season, and certainly presenting to the eye a far richer display of blossoms, can here be enjoyed during the most inclement weather of our long winters. The advantages are so many and important, of having the green-house connected with the mansion, either through the library or parlor, that we have often wondered at their generally isolated situation. This is particularly the case around Boston, where there is scarcely a green-house, certainly not one of any size or beauty, which connects with the living rooms to the dwelling house. We hope that those who are about erecting plant structures will bear this in mind.”

- Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), October 1839, “Some Remarks upon several Gardens and Nurseries in Providence, Burlington, (N.J.) and Baltimore,” describing Residence of Dr. T. Edmonson Jr. (Magazine of Horticulture 5: 374)[14]

- ". . . Attached to the garden is a green-house, hot-house, and conservatory with a blank roof in the old style: this is made use of to preserve a number of large old lemons and orange trees."

- Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), August 1841, describing the residence of J. A. Perry, New York, NY (Magazine of Horticulture 7: 367–68)[15]

- “The conservatory, forming one wing of the house, and the hot-house, we have before described, (Vol. V., p. 30.) Since then, there has been a palm-house added, which is one of the most lofty structures, as well as the only one, we believe, devoted to that peculiar purpose, in the country. It is the principal object of attraction, and connects the green-house and hot-house together, being built between the two. It is sixty feet long, and thirty-one wide, and twenty-eight feet high in the centre. It is built with a span roof, and side-sashes, which reach to the ground. The side lights are double, in order to keep out the cold air in winter, as it would require a great consumption of fuel, unless double sashes or outside shutters were used.

- “The interior arrangements of the palm-house are simply a large bed in the centre, with a walk of four feet wide all round it. The hot-water pipes, three in number, occupy one side of the walk. The palms, and other plants, are planted out in the bed, and presented a most vigorous and thrifty appearance.”

- Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), August 1841, describing the residence of James Dundas, Philadelphia, PA (Magazine of Horticulture 7: 420)[16]

- “The house fronts on Walnut street, with a small conservatory attached in the rear, and entered from one of the parlors. The house is built in the Grecian style, and the conservatory finished in good keeping with the architecture of the house, with pilasters, and a deep and ornamented entablature: it is about twenty feet in length, with a semicircular end, so that when the folding-doors are thrown open between that and the parlor, the whole appears as an oblong oval room, the end of the parlor being also semicircular: the doors which open into the hall and front room at the corners are set with the conservatory. In the evening, when the parlor is lighted up, this must have a most brilliant effect. The conservatory as well as the drawing-room, opens into a piazza.”

- Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), October 1843, describing the conservatory of James E. Teschemacher, Boston, MA (Magazine of Horticulture 9: 379–81)[17]

- “The old arrangement we described in our notice of the Conservatory some time ago. (Vol. V., p. 219.) It was that of a central, circular stage, diminishing to the top. On this stage nearly all the plants were placed, but in such crowded manner, that the effect of any fine specimen was entirely lost. Only a small portion of the stage being seen at one time, no breadth of foliage could be obtained, and the effect intended by the arrangement,—that of presenting a mass of plants to the eye at once,—was quite destroyed. In looking at the stage every view was nearly the same; and whether seen from the gallery above, or the walk beneath, there was the same monotonous scene, a pyramid of plants. Besides these objections to the old arrangement, in regard to effect, one-half of the plants were always in the shade, and soon became sickly and diseased: the other half were exposed to the fierce rays of the sun, and many of the leaves, particularly of the camellias, were scorched and much burnt every spring. The difficulty of watering the plants was also very great, and attended with much loss of time.

- “The entrance before was through the centre of the house, beneath the central stage: that entrance is now floored over, and in the same circle where the stage formerly stood, the plants are now placed, immediately upon the floor. The stairs are to the right and left of the entrance door, and land in the rear of the outer row of plants, so that no distinct view of the interior is obtained, until the spectator turns up one of the walks which cross the house, when a splendid scene is presented to the eye. The dome of the conservatory is supported by four pillars, placed so as to form the angles of a square in the centre: at the base of these are large boxes filled with rich earth, in which climbing plants are placed, intended to entwine and wreath around the columns with flowers and foliage. . . The open space formed by the square, is intended for seats, from whence every plant in the house may be partially seen, and the finest of them immediately before the eye. . . The surface of the boxes being covered, afford an opportunity for the display of rare subjects, such as the exquisite Achimenes longiflora, gloxinias, new fuchsias, &c. On one side there is a crescent-shaped stage reaching to the gallery, on which are placed those plants which show to good advantage, and are too large to stand upon the floor. Arranged thus, the whole show at one view, and from the four walks, which cross the circle, dividing it, as it were, into four quarters, as well as from the gallery, entirely new scenes follow the eye. That credit is certainly due to Mr. Teschemacher for the very picturesque and tasteful arrangement of the plants. There is nothing like the formal stiffness which was before exhibited, and one may now sit down and imagine himself in the midst of an open garden, studded with luxuriant creepers and shrubs. To young gardeners, and indeed to the amateurs of plants, there is the opportunity of a good study to learn the method of arrangement, which shall combine picturesque effect with economy of room. We have often thought if there was any one thing in which many of our best gardeners and amateur cultivators show a want of taste, it was in the arrangement of their greenhouse plants. There are indeed no walks to make, by which

- ‘Each ally has its brother,’

- but the principle is followed up of placing plant opposite plant, and making up a stage to resemble a clipt hedge, with all its formality. This is wrong, but yet it is as well to do this, as to attempt any other arrangement, unless guided by principles of true taste, which can only be acquired by some thought and study. We would certainly invite gardeners and amateurs to look at the Conservatory under its new arrangement.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, October 1847, describing Montgomery Place, country home of Mrs. Edward (Louise) Livingston, Dutchess County, NY (quoted in Haley 1988: 52)[18]

- “ . . . we emerge in the neighborhood of the CONSERVATORY.

- “This a large, isolated, glazed structure, designed by MR. CATHERWOOD, to add to the scenic effect of the pleasure grounds. On its northern side are, in summer, arranged the more delicate green-house plants; and in front are groups of large Oranges, Lemons, Citrons, Cape Jasmines, Eugenias, etc., in tubs—plants remarkable for their size and beauty.” [See Fig. 6]

- Tuthill, Louisa C. (Louisa Caroline), 1848, describing the estate of Gerard Halleck, New Haven, CT (1848; repr., 1988: 284)[19]

- “An Elizabethan villa, the country-seat of Gerard Halleck, Esq. It stands by the water-side, near the shore of New Haven harbour. The observatory commands an extensive and beautiful prospect. . . The large conservatory on the southern side, with its range of Gothic windows, adds much to the beauty of the exterior. Sydney M. Stone, architect.” [Fig. 9]

- Earle, Pliny, January 1848, describing Bloomingdale Asylum for the Insane, New York, NY (Journal of Medicine 10: 61)

- “The principle out-buildings on the premises are a barn, including stables and carriage-house, an ice-house, and a green-house, or conservatory. The barn is large, and built of stone in the most substantial manner. The green-house contains about seven hundred plants, many of them rare and beautiful exotics.”

- Massachusetts Horticultural Society, September 1848, describing the Twentieth Annual Exhibition in Boston, MA (1848: 4)

- “There was a great collection of Pot Plants from the various conservatories, and green-houses of our amateurs and nurserymen, but for the want of room they were not exhibited to the greatest advantage. . . Old Faneuil Hall never looked more lovely. The hallowed influence of fruits and flowers, seemed to have dissipated the political atmosphere of mists in which the place is wont to be shrouded, and it appeared to smile like the garden of Eden."

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1849, describing the Camac Cottage, near Philadelphia, PA (1849; repr., 1991: 58)[20]

- “. . . there is a conservatory attached to the house, in which the plants in pots are hidden in beds of soft green moss, and which, in its whole effect and management, is more tasteful and elegant than any plant house, connected with a dwelling, that we remember to have seen.” [Fig. 10]

- Justicia [pseud.], March 1849, “A Visit to Springbrook,” seat of Caleb Cope, near Philadelphia, PA (Horticulturist 3: 411)[21]

- “Connected with the dwelling is a span-roofed conservatory, filled with plants in bloom, including a carriage entrance, under glass, for the convenience of taking up the family in time of rain or sickness. Farther south is another span-roofed house, 32 feet long; one side for Geraniums, embracing 60 of the finest sorts and the other side for choice fancy Roses, many of them now in full bloom. Connected with this house is another, similar to it, for Azaleas, Rhododendrons, and other showy blooming plants of like treatment.”

- Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), December 1849, describing Oatlands, residence of D. P. Manice, Hempstead, NY (Magazine of Horticulture 15: 529–30)[22]

- “The house is a handsome building, in a kind of castellated gothic, standing about fifty feet from the road, with the conservatory and hothouse, and flower garden on the left,—the kitchen garden and forcing-houses on the right,—and the lawn and pleasure ground, in the rear of the house, separating it from the park. . .

- “The conservatory is a large and lofty building, sixty feet by thirty, and fourteen feet to the eaves, with a span roof. The interior arrangements are a narrow border on the sides and ends, with a broad walk all round, and a large paved bed in the centre, on which the plants are placed. The conservatory and stove are both heated with a powerful hot water apparatus, by which a good temperature is easily obtained, though so many cubic feet of air are to be warmed. The conservatory connects with the stove, transversely, from which it is entered at one end, opening at the other to the flower garden.”

- Londoniensis [pseud.], October 1850, “Notes and Recollections of a Visit to the Nurseries of Messrs. Hovey & Co., Cambridge” (Magazine of Horticulture 16: 443)[23]

- “Entering by this gate you find yourself upon a fine, smooth, promenade walk, about sixteen feet wide, bordered on each side by circular masses of exotic flowers; directly in front of you stands a span-roofed plant-house, or conservatory, of Grecian construction. It is about ninety feet long and twenty feet wide, with a low span-roof. The entrance-front, which is ascended by a broad flight of steps, is formed by projecting part of the main house, and comprises the office, gardener’s room, &c. The garden front shows a fine facade. The whole is highly finished with a heavy entablature, and pilasters between all the sashes, which reach to the floor all round.

- “It is seldom that a house like this, in an architectural point of view, is to be found in a nursery establishment; and its position is admirable, both as regards convenience and effect.”

Citations

- La Quintinie, Jean de, 1693, “Dictionary,” The Compleat Gard’ner (1693; repr., 1982: n.p.)[24]

- “A Conservatory is a close place where Orange-Trees, and other tender Plants are placed till warm weather come in. See Green house.”

- Chambers, Ephraim, 1741–43, Cyclopaedia (1741: 1:n.p.)[25]

- “CONSERVATORY, in gardening, See GREEN-House. . .

- “GREENHOUSE, or conservatory; a house of shelter in a garden, contrived for preserving the more tender and curious exotic plants, which will not bear the winter’s cold abroad in our climate. See EXOTIC.

- “Greenhouses, as now built, serve not only as conservatories, but likewise as ornaments of gardens; being usually large and beautiful structures, in form of galleries, wherein the plants are handsomely ranged in cases for the purpose. See GARDEN.”

- Anonymous, 1798, Encyclopaedia (1798: 8:128–29)[26]

- “GREEN-HOUSE, or Conservatory, a house in a Garden, contrived for sheltering and preserving the most curious and tender exotic plants, which in our climate will not bear to be exposed to the open air, especially during the winter season. These are generally large and beautiful structures, equally ornamental and useful.

- “The length of greenhouses must be proportioned to the number of plants intended to be preserved in them, and cannot therefore be reduced to rule: but their depth should never be greater than their height in the clear; which, in small or middling houses, may be 16 or 18 feet, but in large ones from 20 to 24 feet; and the length of the windows should reach from about one foot and a half above the pavement, and within the same distance of the cieling, which will admit of a corniche round the building over the heads of the windows. . .

- “Whilst the front of the greenhouse is exactly south, one of the wings may be made to face the south-east and the other the south-west. By this disposition the heat of the sun is reflected from one part of the building to the other all day, and the front of the main greenhouse is guarded from the cold winds. . . In each of these there should be a fire-place, with flues carried up against the back-wall, through which the smoke should be made to pass.”

- Repton, Humphry, 1803, Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1803: 103–4)[27]

- “There is no ornament of a flower garden more appropriate than a conservatory or greenhouse, where the flower garden is not too far from the house; but amongst the refinements of modern luxury, may be reckoned that of attaching a green-house to some room in the mansion, a fashion with which I have so often been required to comply, that it may not be improper in this work, to make ample mention of the various methods by which it has been effected in different places.”

- M’Mahon, Bernard, 1806, The American Gardener’s Calendar (1806: 82–83)[28]

- “The Green-house and Conservatory have been generally considered as synonymous; their essential difference is this: in the Green-house, the trees and plants are either in tubs or pots, and are placed on stands or stages during the winter, till they are removed into some suitable situation abroad in summer. In the Conservatory, the ground plan is laid out in beds and borders, made up of the best compositions of soils that can be procured, three or four feet deep. In these the trees or plants, taken out of their tubs or pots, are regularly planted, in the same manner as hardy plants are in open air. This house is roofed, as well as fronted with glass-work, and instead of taking out the plants in summer, as in the Green-house, the whole of the glass-roof is taken off, and the plants are thus exposed to the open air.”

- Abercrombie, John, with James Mean, 1817, Abercrombie’s Practical Gardener, or Improved System of Modern Horticulture (1817: 460, 557)[29]

- “When the horticultural establishment includes a conservatory, it is proper to have it in sight, and connected with the ornamented grounds; because the style of such a building, the plants within, and the scene without, under a tasteful arrangement, harmonize in character and effect. . .

- “A GREEN-HOUSE, or Conservatory, is a building adapted, by its situation and construction, for the seasonable shelter and nurture of such exotics from warmer climates as are not hardy enough to endure the colder vicissitudes of our year, but yet neither require, nor would prosper under, the intense and more artificial culture of a Hot-house. . .

- “A Green-house may be made a very ornamental object as a structure; the plants within comprise some of the most curious and elegant productions which the art of the Gardener can nurture; its situation is, therefore, usually in a conspicuous part of the Pleasure Ground, contiguous to the family residence. The front of the building should stand directly to the south, and the ends have an open aspect to the east and west.

- “Some persons distinguish between a Greenhouse and Conservatory; making the latter contain a border and pit: but this is to mix two systems of culture, which will proceed better separately.”

- Hosack, David, 1824, An Inaugural Discourse Delivered Before the New-York Horticultural Society (1824: 22)[30]

- “. . . we should also be provided with suitable conservatories for those plants which may be introduced from abroad. And I may add, that the buildings thus erected should be constructed agreeably to the most correct principles of architecture; for every such edifice, in a place of great public resort, will necessarily have its influence in forming and directing the general taste of the country.”

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826: 794, 811–14)[31]

- “6099. The green-house or conservatory is generally placed in the flower-garden, provided these structures are not appended to the house. . .

- “6161. The hot-houses of floriculture are the frame, glass case, green-house, orangery, conservatory, dry-stove, the bark or moist stove, in the flower-garden, or pleasure-ground; and the pit and hot-bed in the reserve-garden. In the construction of all of these the great object is, or ought to be, the admission of light and the power of applying artificial heat with the least labor and expense. . .

- “6165. The most suitable description of greenhouse or conservatory for the flower-garden is that with span roof. . . because such a house has no visible ‘hinder parts,’ back sheds, stock-holes, or other points of ugliness, with which it is difficult to avoid associating all the shed, or lean-to forms of glazed buildings with back walls. . .

- “6174. The conservatory is a term generally applied by gardeners to plant-houses, in which the plants are grown in a bed or border without the use of pots. They are sometimes placed in the pleasure-ground along with the other hot-houses; but more frequently attached to the mansion. The principles of their construction is in all respects the same as for the green-house, with the single difference of a pit or bed of earth being substituted for the stage, and a narrow border instead of surrounding flues. The power of admitting abundance of air, both by the sides and roof, is highly requisite both for the green-house and conservatory; but for the latter, it is desirable, in almost every case, that the roof, and even the glazed sides, should be removable in summer.” [Fig. 11]

- Teschemacher, James E., May 1, 1835, “On Horticultural Architecture” (Horticultural Register 1: 158)[32]

- “In many houses which are warmed throughout, the entrance is frequently appropriated to plants, and where it is feasible why may not a glass roof be substituted for the shingle or slate, thus affording the necessary vertical light? advance one step farther by giving a glass front and we have a green-house. . .

- “The interior arrangement of this small conservatory can be fixed to suit different tastes, but I should prefer any to the usual mode of a straight walk down the centre; for instance, the roof might be additionally supported by three or four slender pillars up which might be trained Lophospermum, Acacia pubescens, Cobea scandens, Eccremocarpus scaber or other beautiful climbing plants.”

- Loudon, Jane, 1845, Gardening for Ladies (1845: 166)[33]

- “CONSERVATORY.—This term originally implied a house in which orange-trees, and other large shrubs, or small trees, were preserved from frost during the winter; but at present it is applied to houses with glass roofs, in which the plants are grown in the free soil, and allowed to assume their natural shapes and habits of growth. A conservatory is generally situated so as to be entered from one of the rooms of the house to which it belongs; and from which it is often separated only by a glass door, or by a small lobby with glass doors. It should, if possible, have one side facing the south; but if it is glazed on every side, it may have any aspect, not even excepting the north: though in the latter case, it will only be suitable for very strong leathery-leaved evergreens, such as Camellias, Myrtles, &c. . . The plants should be of kinds that will grow in a few years nearly as high as the glass; and they should, as much as possible, be all of the same degree of vigour, otherwise the stronger kinds will fill the soil with their roots, and overpower the weaker. . . The pillars which support the roof, and, to a certain extent, the under side of the rafters, may be clothed with creepers. . . The most suitable plants for conservatories are those that flower in the winter season, or very early in the spring.”

- Johnson, George William, 1847, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening (1847: 165, 404, 584)[34]

- “CONSERVATORY. This structure is a green-house communicating with the residence, having borders and beds in which to grow its tenant plants; or it may be an appendage to the dwelling, of moderate size, into which the plants from the green-house are removed whilst in bloom, thus concentrating the more attractive specimens, and presenting a continuous show of flowers. . .

- “ORANGERY is a green-house or conservatory devoted to the cultivation of the genus Citrus. . .

- “[TERRACES. . .] Mr. Loudon is more practical on this subject, and observes. . .

- “‘In some cases the terrace-walls may be so extended as to enclose ground sufficient for a level plot to be used as a bowling green. These are generally connected with one of the living-rooms, or the conservatory; and to the latter is frequently joined an aviary, and the entire range of botanic stoves.’—Enc. Gard.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1849, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849; repr., 1991: 448–49, 454)[35]

- “The Conservatory or the Green-House is an elegant and delightful appendage to the villa or mansion, when there is a taste for plants among the different members of a family. Those who have not enjoyed it, can hardly imagine the pleasure afforded by a well-chosen collection of exotic plants, which, amid the genial warmth of an artificial climate, continue to put forth their lovely blossoms, and exhale their delicious perfumes, when all out-of-door nature is chill and desolate. The many hours of pleasant and healthy exercise and recreation afforded to the ladies of a family, where they take an interest themselves in the growth and vigor of the plants, are certainly no trifling considerations where the country residence is the place of habitation throughout the whole year. . .

- “The difference between the green-house and conservatory is, that in the former, the plants are all kept in pots and arranged on stages, both to meet the eye agreeably, and for more convenient growth; while in the conservatory, the plants are grown in a bed or border of soil precisely as in the open air. “Though a conservatory is often made an expensive luxury, attached only to the better class of residences, there is no reason why cottages of more humble character should not have the same source of enjoyment on a more moderate scale. A small green-house, or plant cabinet, as it is sometimes called, eight or ten feet square, communicating with the parlor, and constructed in a simple style, may be erected.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, December 1849, “Design for a Villa with a Conservatory Attached” (Horticulturist 4: 263–64)[36]

- “From the parlor, a door opens into the greenhouse, or conservatory. This is placed so as to form a wing on one side of the house, which is balanced by the kitchen wing on the other side. We have introduced this to show how a simple green-house may be treated, so as to give it some architectural character,—as we but too frequently see mere nursery-like glazed sheds, joined to houses otherwise in good taste, the effect of which is never satisfactory. A conservatory, properly so called,—which differs from a green-house in the plants being chiefly planted in the ground, instead of pots,—is the most satisfactory plan for such a structure when it is attached to a dwelling; because, although the glazed roof is partly taken out in summer, the plants remain, and the interior never has the deserted appearance of most green-houses at that season, but is an agreeable sight at all times.” [Fig. 12]

- Webster, Noah, 1850, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1850: 252)[37]

- “CON-SERV’A-TO-RY, n. A place for preserving any thing in a state desired, as from loss, decay, waste, or injury. . .

- “2. A greenhouse for exotics, often attached to a dwelling-house as an ornament. In large conservatories, properly so called, the plants are reared on the free soil, and not in pots. Brande.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1850, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850; repr., 1968: 305, 323)[38]

- “The broad and massive veranda. . . —the full second story, overshadowed by the overhanging eaves—the steep roof, to shed the snow and afford a well ventilated attic, and the tasteful or convenient appendages of conservatory for plants on one side and kitchen offices on the other,—these are all expressive of the comparatively modest but cultivated tastes and life of substantial country residents in the older parts of the Northern states. . .

- “[Referring to Design XXVIII.] When we notice, also, the conservatory, extending itself on one side, and the kitchen on the other, with a long veranda in the rear; it is easy to see that this design indicates the residence of a family thoroughly at home in the country, and understanding how best to enjoy it.” [Fig. 13]

Images

Inscribed

Solomon Drowne, Botanic Garden, 1818, 1818. The "conservatory" inscription can be found between the "shrubbery" and "college inclosure" inscriptions, to the left.

J. C. Loudon, Greenhouse or conservatory for a flower-garden, with a span roof, in An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826), 811, fig. 568.

Robert Mills, Elevation of the South Front and Plan of the First Floor, National Institute, February 1841.

Anonymous, “The Conservatory,” Montgomery Place, in A. J. Downing, ed., Horticulturist 2, no. 4 (October 1847): 159, fig. 28.

Anonymous, “English Flower-Garden,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849), 434, fig. 78. "b, the conservatory."

Anonymous, “Villa at Brooklyn, N.Y., with the Conservatory attached,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849), 453, fig. 79. The conservatory is the room on the left with full length windows and plants inside.

Anonymous, A greenhouse and a conservatory, in A. J. Downing, ed., Horticulturist 5, no. 3 (September 1850): 111, figs. 19 and 20.

Robert B. Leuchars, Ground plan of conservatory designed for gentleman’s country seat, in A Practical Treatise on the Construction, Heating, and Ventilation of Hothouses (1850), 95, fig. 32.

Associated

John Archibald Woodside, Lemon Hill, 1807.

Hugh Reinagle, Elgin Garden on Fifth Avenue, c. 1812.

William Satchwell Leney after Hugh Reinagle, “View of the Botanic Garden of the State of New York,” in David Hosack, Hortus Elginensis (1811), frontispiece.

Alexander Jackson Davis, “The Conservatory,” Montgomery Place, c. 1839.

Anonymous, “Mrs. Camac’s Residence,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849), pl. between 58 and 59, fig. 13.

Anonymous, “Design for a Country House,” in A. J. Downing, ed., Horticulturist 4, no. 6 (December 1849): pl. opp. 249.

Anonymous, “Rural Gothic Villa,” in A. J. Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850), pl. opp. 322, fig. 148.

Henry Gritten, Springside: View of Barn Complex and Gardens, 1852.

Attributed

Robert Squibb, Green-House: front and back walls, in The Gardener's Calendar for the States of North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia (1827), frontispiece.

Robert B. Leuchars, Orangery at Clifton Mansion, in A Practical Treatise on the Construction, Heating, and Ventilation of Hothouses (1850), fig. 14.

Notes

- ↑ The purpose of this invention was “to conserve greens,” as noted by Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe et al., eds., The Oxford Companion to Gardens (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), 234, view on Zotero.

- ↑ A relationship probably exists between the plant cabinet and the cabinet of curiosities, in which rare and exotic natural history specimens were collected, dating from the 16th and 17th century in Europe. See essays in Oliver Impey and Arthur MacGregor, eds., The Origins of Museums: The Cabinet of Curiosities in Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century Europe (Oxford: Clarendon, 1985), especially John Dixon Hunt’s essay, “Curiosities to Adorn Cabinets and Gardens,” 193–203, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jellicoe et al. 1986, 234, view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. Loudon, Hints on the Formation of Gardens and Pleasure Grounds (London: J. Harding, 1812), view on Zotero. See Melanie Simo, Loudon and the Landscape: From Country Seat to Metropolis, 1783–1843 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1988), especially chapters 6 and 7, view on Zotero.

- ↑ David Hosack, A Catalogue of Plants Contained in the Botanic Garden at Elgin: In the Vicinity of New York, Established in 1801 (New York: T. & J. Swords, 1806), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Drayton, “The Diary of Charles Drayton I, 1806,” Drayton Papers, MS 0152, Drayton Hall, SC, view on Zotero.

- ↑ David Hosack, A Statement of Facts Relative to the Establishment and Progress of the Elgin Botanic Garden (New York: C. S. Van Winkle, 1811), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Robert Waln Jr., “An Account of the Asylum for the Insane, Established by the Society of Friends, near Frankford, in the Vicinity of Philadelphia,” Philadelphia Journal of the Medical and Physical Sciences 1 (1825): 225–51, view on Zotero.

- ↑ James Boyd, A History of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1827–1927 (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1929), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Harriet Martineau, Retrospect of Western Travel, 2 vols. (London: Saunders and Otley, 1838), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Joseph Breck, “Gardens, Hot-Houses, &c., in the Vicinity of Boston,” Horticultural Register, and Gardener’s Magazine 2 (February 1, 1836): 41–47, view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. B., “Horticulture in Maine,” Horticultural Register, and Gardener’s Magazine 2 (October 1, 1836): 380–86, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Mason Hovey, “Notes on Some of the Nurseries and Private Gardens in the Neighborhood of New York and Philadelphia, Visited in the Early Part of the Month of March, 1837,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 3, no. 5 (May 1837): 161–69, view on Zotero.

- ↑ C. M. Hovey, “Some Remarks upon Several Gardens and Nurseries, in Providence, Burlington, (N.J.) and Balitmore,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 5, no. 10 (October 1839): 361–76, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Mason Hovey, “Notes Made during a Visit to New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington, and Intermediate Places, from August 8th to the 23rd, 1841,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 7, no. 10 (October 1841): 321–27, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Mason Hovey, “Notes Made during a Visit to New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington, and Intermediate Places, from Aug. 8th to the 23d, 1841,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 7, no. 11 (November 1841): 412–23, view on Zotero.

- ↑ C. M. Hovey, “Calls at Gardens and Nurseries,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 9, no. 10 (October 1843): 379–81, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jacquetta M. Haley, ed., Pleasure Grounds: Andrew Jackson Downing and Montgomery Place (Tarrytown, NY: Sleepy Hollow Press, 1988), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Louisa C. Tuthill, History of Architecture, from the Earliest Times; Its Present Condition in Europe and the United States; with a Biography of Eminent Architects, and a Glossary of Architectural Terms (1848; repr., Philadelphia: Lindsay and Blakiston, 1988),view on Zotero

- ↑ A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America, 4th ed. (1849; repr., Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Justicia [pseud.], “A Visit to Springbrook, the Seat of the President of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 3, no. 9 (March 1849): 411–14, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Mason Hovey, “Notes of a Visit to Oatlands, Hempstead, L.I., N.Y., the Residence of D. F. Manice, Esq.,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 15, no. 12 (December 1849): 529–33, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Londoniensis [pseud.], “Notes and Recollections of a Visit to the Nurseries of Messrs. Hovey & Co., Cambridge,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 16, no. 10 (October 1850): 442–47, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jean de La Quintinie, The Compleat Gard’ner, or Directions for Cultivating and Right Ordering of Fruit-Gardens and Kitchen Gardens, trans. John Evelyn (1693; repr., New York: Garland, 1982), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Ephraim Chambers, Cyclopaedia, or An Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences. . . , 5th ed., 2 vols. (London: D. Midwinter et al., 1741), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, Encyclopaedia, or A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Miscellaneous Literature, 18 vols. (Philadelphia: Thomas Dobson, 1798), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Humphry Repton, Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (London: Printed by T. Bensley for J. Taylor, 1803), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bernard M'Mahon, The American Gardener’s Calendar: Adapted to the Climates and Seasons of the United States. Containing a Complete Account of All the Work Necessary to Be Done. . . for Every Month of the Year. . . (Philadelphia: Printed by B. Graves for the author, 1806), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Abercrombie, Abercrombie’s Practical Gardener Or, Improved System of Modern Horticulture (London: T. Cadell and W. Davies, 1817), view on Zotero.

- ↑ David Hosack, An Inaugural Discourse, Delivered before the New-York Horticultural Society at Their Anniversary Meeting, on the 31st of August, 1824 (New York: J. Seymour, 1824), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, 4th ed. (London: Longman et al., 1826), view on Zotero.

- ↑ James E. Teschemacher, “On Horticultural Architecture,” Horticultural Register, and Gardener’s Magazine 1 (May 1, 1835): 157–61, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jane Loudon, Gardening for Ladies; and Companion to the Flower-Garden, ed. A. J. Downing (New York: Wiley & Putnam, 1845), view on Zotero.

- ↑ George William Johnson, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening, ed. David Landreth (Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1847), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America, 4th ed. (1849; repr., Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. Downing, “Design for a Villa with a Conservatory Attached,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 4, no. 6 (December 1849): 263–64, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language (Springfield, MA: George and Charles Merriam, 1850), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses; Including Designs for Cottages, Farm-Houses, and Villas (New York: D. Appleton, 1850; repr., New York: Da Capo, 1968), view on Zotero.