Hothouse

History

The hothouse, or hot house, was a plant-keeping structure that provided enough heat to permit the cultivation of tropical and semi-tropical plants in temperate climates. The hothouse often formed part of a greenhouse [Figs. 1 and 2], although very often the terms were used synonymously and interchangeably with “conservatory.” Bernard M’Mahon (1806) wrote that the difference between a greenhouse and hothouse was that a greenhouse had only enough artificial heat to “keep off frost and dispel damps,”[1] whereas the latter had an interior stove and was covered in more glass (view text) (see Conservatory, Greenhouse, and Orangery).

An area’s climactic zone determined the extent to which a heating system was necessary. Heat could be generated in several ways. Dry heating systems included charcoal fires contained in metal pots and wheelbarrows that were placed within the hothouse to give off warmth. More sophisticated hypocaust systems used cellar boilers that circulated heat through flues. This latter type, which was developed by the ancient Romans, has been found in archaeological sites in Maryland, dating as early as around 1730.[2] John Evelyn, in his 1693 translation of Jean de La Quintinie, suggested caking the back wall of a hothouse with a thick layer of dry dung, fixed in place with wooden lathes.[3] This technique, or a related one that called for manure piles to be placed under the benches, could let off heat as the manure decomposed. Perfected in the early 1820s, a wet-air or steam system circulated heated water through pipes placed underneath benches. Opening and closing these water pipes allowed the regulation of heat. This kind of system, however, was considered a luxury until the late 19th century. A hothouse could also be built as a lean-to glasshouse, thus benefiting from the heating system of the main house, to which it was attached [Fig. 3].

In the early to mid-19th century, as fashions changed regarding the choice of certain plants, specialized hothouses were built and named accordingly. For example, the grapery or vinery, the peachery, pinery (for pineapples), palm house, rose house, camellia house, and geranium house, were built according to the specific heating and lighting requirements of each plant type.

—Therese O’Malley

Texts

Usage

- Redwood, Abraham, Jr., c. 1760, in a letter to his plantation manager, describing Redwood Farm, seat of Abraham Redwood Jr., Portsmouth, RI (Rhode Island Landscape Survey)

- “I would desire you send to me one hhd of good rum and one hhd of good sugar and I desire that you speak to your overseer to put up in Durt one dozen of Small orange Trees that has bore one or two years with the young fruit upon them, if to be had that has bore two or three years of Saffadella trees, four young figg trees and some Guavas roots, to put in my greenhouse, for I have made a garden of 1 1/2 acres of land and I have built a green house twenty-two feet long, Twelve feet wide and Twelve feet high, and a hotte house Sixteen feet long Twelve feet wide and Twelve feet high, and I have growing in my greenhouse Fifty young fruit trees from six inches to four feet high, and my Gardner says ye largest will not bear fruit these two years, and I have hotte house Strawberries, Bush beans and Crownations in Blossom.”

- Drowne, Samuel, June 24, 1767, describing Redwood Farm, seat of Abraham Redwood Jr., Portsmouth, RI (Rhode Island Landscape Survey)

- “Mr. Redwood’s garden. . . is one of the finest gardens I ever saw in my life. In it grows all sorts of West Indian fruits, viz: Oranges, Lemons, Limes, Pineapples, and Tamarinds and other sorts. It has also West Indian flowers—very pretty ones—and a fine summer house. It was told my father that the man that took care of the garden had above 100 dollars per annum. It had Hot Houses where things that are tender are put for the winter, and hot beds for the West India Fruit. I saw one or two of these gardens in coming from the beach.”

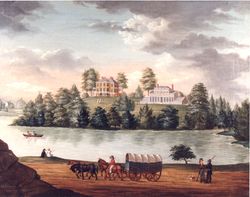

- Vaughan, Samuel, 1787, describing Mount Vernon, plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (quoted in Norton and Schrage-Norton 1985: 142)[4]

- “Before the front of the house. . . there are lawns, surrounded with gravel walks 19 feet wide. with trees on each side the larger, for shade. outside the walks trees & shrubberies. Parralel [sic] to each exterior side a Kitchen Gardens. with a stately hot house on one side.” [Fig. 4]

- Hamilton, William, 1789, in a letter to his secretary, Benjamin Hays Smith, describing The Woodlands, seat of William Hamilton, near Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Madsen 1988: A4)[5]

- “In my Hurry at the time of coming off from Home I omitted to put in the ground the exotic Bulbous roots & as I gave no direction to Hilton respecting them they may suffer more especially as they were all taken out of the pots & left dry on the Back flue of the Hot House.” [Fig. 5]

- Bentley, William, June 12, 1791, describing Pleasant Hill, seat of Joseph Barrell, Charlestown, MA (1962: 1:264)[6]

- “[June] 12. Was politely received at dinner by Mr Barrell, & family, who shewed me his large & elegant arrangements for amusement, & philosophic experiments. . . His Garden is beyond any example I have seen. . . Below is the Hot House. In the apartment above are his flowers admitted more freely to the air, & above a Summer House with every convenience. . . No expense is spared to render the whole amusing, instructive, & friendly.”

- Anonymous, 1798, describing Mount Airy, property of John Tayloe II, Richmond County, VA (quoted in Lounsbury 1994: 184)[7]

- “[Tayloe constructed a] Green & Hot house for £150; the smaller hothouses were attached to each side of the larger greenhouse.”

- Booth, William, 1799, describing in the Federal Gazette and Baltimore Advertiser a sale of botanical rarities in Baltimore (quoted in Sarudy 1989: 115)[8]

- “To Botanists, Gardeners and Florists, and to all other gentlemen, curious in ornamental, rare exotic or foreign plants and flowers, cultivated in the greenhouse, hot-house, or stove, and in the open ground. A large and numerous variety of such rarities is now offered for sale.”

- Searson, John, 1799, describing Mount Vernon, plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (quoted in Norton and Schrage-Norton 1985: 49)[4]

- “The gardens beautiful this time of year Requites the husbandman for all his care But, see with wonder, said my roving mind, A hot-house here a stranger soon will find: Hundreds of flow'rs and herbs you here may see That in a common garden cannot be.” [Fig. 6]

- Bentley, William, June 19, 1800, describing Elias Hasket Derby Farm, Peabody, MA (1962: 2:341–42)[6]

- “19. . . Stopped at Mr. Derby’s Garden in which we experienced the utmost attention of Mr. Heusler the Gardener. He first fed us with Cherries, & Strawberries, & then exhibited the Luxuries of the place. We saw Lemons growingin the Hot House. A great variety of the Aloe plant was shewn to us. We were shewn 5 species of the Geranium. We saw the prickly pear in flower, & received some of the flowers. I brought away a specimen of the Roof House leek, which was a beautiful species.”

- Clitherall, Eliza Caroline Burgwin (Caroline Elizabeth Burgwin), active 1801, describing a garden in Wilmington, NC (Lower Cape Fear Historical Society, Autobiography and Diary of Mrs. Eliza Clitherall, 2:1–3)

- “The Gardens were large, laid out in the English style—a Creek would thro’ the largest, upon its banks grew native shrubbery; in this Garden were several Alcoves, Summer Houses, a hothouse—an Octagon summer house.”

- Anonymous, January 30, 1804, describing possibly Vauxhall Garden, in New York, NY (New York Gazette & General Advertiser)

- “To be let. . . The land contains about 3 acres, on which is a great variety of fruit of the best quality, a hot-house, etc. and is in every respect well calculated for a gardener, or a summer residence.” [Fig. 7]

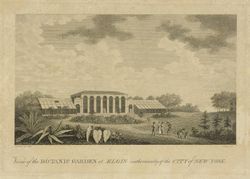

- Hosack, David, 1806, describing Elgin Botanic Garden, New York, NY (1806: 3–4)[9]

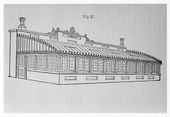

- “In the year 1801 I purchased, of the Corporation of the city of New-York, twenty acres of ground; the greater part of which is now in cultivation. Since that time. . . two Hot-Houses are now erecting for the preservation of those plants which require a greater degree of heat.” [Fig. 8]

- Drayton, Charles, November 2, 1806, describing The Woodlands, seat of William Hamilton, near Philadelphia, PA (1806: 55—56)[10]

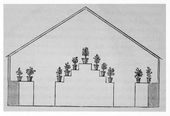

- “The Conservatory consists of a green house, & 2 hot houses—one being at each end of it. The green house may be about 50 feet long. The front only is glazed. Scaffolds are erected, one higher than another, on which the plants in pots or tubs are placed—so that it is representing the declivity of a mountain. At each end are step-ladders for the purpose of going on each stage to water the plants—& to a walk at the back-wall. On the floor a walk of 5 or 6 feet extends along the glazed wall & at each end a door opens into an Hot house—so that a long walk extends in one line along the stove walls of the houses & the glazed wall of the green house.

- “The Hot houses, they may extend in front, I suppose, 40 feet each. They have a wall heated by flues—& 3 glazed walls & a glazed roof each. In the center, a frame of wood is raised about 2 1/2 feet high, & occupying the whole area except leaving a passage along by the walls. In the flue wall, or adjoining, is a cistern for tropic aquatic plants. Within the frame, is composed a hot bed; into which the pots & tubs with plants, are plunged. This Conservatory is said to be equal to any in Europe. It contains between 7 & 8000 plants. To this, the Professor of botany is permitted to resort, with his Pupils occasionally.” [Fig. 9]

- Memorial of the Columbian Institute, December 1818, describing the Columbian Institute, Washington, DC (quoted in O’Malley 1989: 123)[11]

- “[Columbian Institute lottery for] enclosing the grounds, for the erection of their hall—their laboratory—their hot and green houses,—their library and museum, and for the cultivation of the botanic garden, wherein they hoped ‘to soon present to the view of their fellow citizens specimens of all the plants of this middle region of our country, with others exotic and domestic. . . for the promotion of a great national object. . .’”

- Wailes, Benjamin L. C., December 26, 1829, describing D. and C. Landreth’s Nursery on Federal Street, Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Moore 1954: 355)[12]

- “Rode out to Landreths Nursery and passed through his hot house [which contained] a number of dwarf Orange & Lemon trees in fruit, a few Camelia, Japonicas in Bloom.” [Fig. 10]

- Wailes, Benjamin L. C., December 29, 1829, describing Lemon Hill, estate of Henry Pratt, Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Moore 1954: 359–60)[12]

- “. . . the hot house is said to be the largest in the US. It is filled to overflowing with the choicest Exotics: the Chaddock Orange of different kinds & the Lemon loaded with fruit. There are two coffee trees with their berries. Some few shrubs were in flower & others seeded, & I was politely furnished with a few seed of 2 varieties of flowers (Myrtle & an accacia). In front of the hot house, one at each end, is a Lion of marble, well executed, & a dog in front. On the roof is a range of marble busts.”

- Committee of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1830, describing Lemon Hill, estate of Henry Pratt, Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Boyd 1929: 432)[13]

- “The treasures contained in the hot and green houses are numerous. Besides a very fine collection of Orange, Lemon, Lime, Citron, Shaddock, Bergamot, Pomgranate and Fig trees in excellent condition and full of fruit, we notice with admiration the many thousand of exotics to which Mr. Pratt is annually adding. The most conspicuous among these, are the tea tree; the coffee tree—loaded with fruit; the sugar cane; the pepper tree; Banana, Plantain, Guva, Cherimona, Ficus, Mango, the Cacti in great splendour, some 14 feet high, and a gigantic Euphorbia Trigonia—19 years old, and 13 feet high. The green houses are 220 feet long by 16 broad; exhibiting the finest range of glass for the preservation of plants, on this continent. . .

- “Mr. Pratt’s are furnished with the rarest productions of every clime, so that the committee place the conservatory of Lemon Hill at the very head of all similar establishments in this country.” [Fig. 11]

- Forman, Martha Ogle, October 12, 1830, describing Rose Hill, home of Martha Ogle Forman, Baltimore County, MD (1976: 292)[14]

- “I rode out with Mrs. Longstreeth to her country seat. I was very much pleased they have a very spacious house handsomely furnished, an elegant green house and hot house and all the grounds in beautiful order.”

- Thacher, James, December 3, 1830, “An Excursion on the Hudson,” describing Hyde Park, seat of David Hosack, on the Hudson River, NY (New England Farmer 9: 156)[15]

- “At an equal distance south, is to be seen the green house and hot house, a spacious edifice, constructed with great architectural taste and elegance, and well calculated for the preservation of the most tender exotics that require protection in our climate. It is composed of a centre and two wings, extending 110 feet in front and from 17 to 20 feet deep. One apartment is appropriated to a large collection of pines.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, January 1837, “Notices on the State and Progress of Horticulture in the United States,” describing Lemon Hill, estate of Henry Pratt, Philadelphia, PA (Magazine of Horticulture 3: 4)[16]

- “For a long time the grounds of Mr. Pratt, at Lemon Hill, near Philadelphia, have been considered the show-garden of that city: and the proprietor, with a praiseworthy spirit, opening his long-shaded walks, cool grottoes, jets d’eau, and the superb range of hot-houses, to the inspection of the citizens, contributed in a wonderful degree to improve the taste of the inhabitants, and to inspire them with a desire to possess the more beautiful and delicate productions of nature.”

- Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), October 1839, “Some Remarks upon several Gardens and Nurseries in Providence, Burlington, (N.J.) and Baltimore,” describing the residence of Dr. T. Edmondson Jr., Baltimore, MD (Magazine of Horticulture 5: 374)[17]

- “Attached to the garden is a green-house, hothouse and conservatory, with a blank roof in the old style: this is made use of to preserve a number of large old lemon and orange trees.” [Fig. 12]

- Willis, Nathaniel Parker, 1840, describing Mount Vernon, plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (1840: 2:38–39)[18]

- “In front of the house is a lawn, containing five or six acres of ground, with a serpentine walk around it, fringed with shrubbery, and planted with poplars. On each side of the lawn stands a garden; the one on the right is a flower-garden, and contains two green-houses, (one built by General Washington, the other by Judge Washington,) a hot-house, and a pinery. It is laid out in handsome walks, with box wood borders, remarkable for their beauty. It contains also a quantity of fig-trees, producing excellent fruit. The other is a kitchen-garden, containing only fruit and vegetables. . .

- “At the extremity of these extensive alleys and pleasure-grounds, ornamented with fruit-trees and shrubbery, and clothed in perennial verdure, stands two hot-houses, and as many greenhouses, situated in the sunniest part of the garden, and shielded from the northern winds by a long range of wooden buildings for the accommodation of servants. From the air of a frosty December morning, we were suddenly introduced into the tropical climate of these spacious houses, where we long sauntered among the groves of the coffee-tree, lemons and oranges, all in full bearing, regaling our senses with the flowers and odours of spring.

- “One of the hot-houses is appropriated entirely to rearing the pine-apple, long rows of which we saw in a flourishing and luxuriant condition. Many bushels of lemons and oranges, of every variety, are annually grown, which, besides furnishing the family with a supply of these fruits at all seasons, are distributed as delicacies to their friends, or used to administer to the comfort of their neighbours in cases of sickness. The coffee-plant thrives well, yields abundantly, and, in quality, is said to be equal to the best Mocha. The branches under which we walked were laden with the fruit, fast advancing to maturity. Among the more rare plants we saw the night-blooming cereas, the guava, aloes of a gigantic growth, the West India plantain, the sweet cassia in bloom, the prickly pear, and many others.”

- Mills, Robert, February 23?, 1841, in a letter to Joel R. Poinsett, describing a design for the national Mall, Washington, DC (Scott, ed., 1990: n.p.)[19]

- “A range of trees is proposed to surround three sides of the square which is intended to be laid open by an iron or other railing, the north side to be enclosed with a high brick wall to serve as a shelter and to secure the various hot houses and other buildings of an inferior character.” [Fig. 13]

- Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), August 1841, “Notes made during a Visit to New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, &c.,” describing the residence of J. A. Perry, New York, NY (Magazine of Horticulture 7: 367–68)[20]

- “The conservatory, forming one wing of the house, and the hot-house, we have before described, (Vol. V., p. 30.) Since then, there has been a palm-house added, which is one of the most lofty structures, as well as the only one, we believe, devoted to that peculiar purpose, in the country. It is the principal object of attraction, and connects the green-house and hot-house together, being built between the two. It is sixty feet long, and thirty-one wide, and twenty-eight feet high in the centre. It is built with a span roof, and side-sashes, which reach to the ground. The side lights are double, in order to keep out the cold air in winter, as it would require a great consumption of fuel, unless double sashes or outside shutters were used.

- “The interior arrangements of the palm-house are simply a large bed in the centre, with a walk of four feet wide all round it. The hot-water pipes, three in number, occupy one side of the walk. The palms, and other plants, are planted out in the bed, and presented a most vigorous and thrifty appearance.”

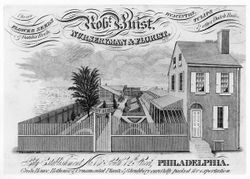

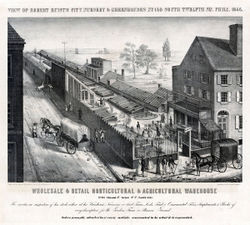

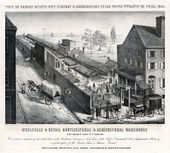

- Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), August 1841, “Notes made during a Visit to New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, &c.,” describing the grounds of Robert Buist’s City Nursery and Greenhouse, Philadelphia, PA (Magazine of Horticulture 8: 124)[21]

- “On it is a green-house, forty feet long; a camellia-house facing the north, forty feet; a hothouse, forty feet; and a geranium-house; about forty feet, the whole being a connected range. In addition to this, there is a rose-house, lately erected, about forty feet long. The whole we found well filled, for the season of the year, with a choice collection of healthy and well grown plants. The camellias were in excellent health; they are kept in the house the year round.” [Fig. 14]

- Horticola [pseud.], March 1852, “Notes on Gardens and Country Seats Near Boston,” describing Bellmont Place, residence of John Perkins Cushing, Watertown, MA (Horticulturist 7: 127)[22]

- “The principal feature of this place is the fine range of hot-houses, which are erected within an enclosure surrounded by a brick wall, and finely trellised for training fruit trees on its ample surface. There is a fine range of hot-houses on the southern wall, some three hundred feet long, with inferior ranges on the eastern and western walls for peaches. The conservatory, in the center, is a noble house, though somewhat badly arranged with regard to plant growing; yet the effect is good, where the plants are nicely arranged on the stages, and covered with bloom, as was the case during our visit.”

- Horticola [pseud.], March 1852, “Notes on Gardens and Country Seats Near Boston,” describing Oakley Place, seat of William Pratt, Boston, MA (Horticulturist 7: 127)[22]

- “The hot-houses [of Oakley Place] here are in excellent order, and a summer plant house was erected last year for arranging the camellias in during the summer months. This novel structure is perfectly unique, having the plan and elevation of a common span roofed green-house, but covered roof and sides with slats (narrow strips of boards) two inches wide, diamond fashion. This is a most useful house, as it shades the plants from the hot sun, yet admits sufficient air and light to enable them to mature their growth and buds.”

Citations

- Chambers, Ephraim, 1741, Cyclopaedia (1741: 1:n.p.)[23]

- “HOT-HOUSE. See STOVE, HYPOCAUSTUM, &c.”

- Salmon, William, 1762, Palladio Londinensis (1762: n.p.)[24]

- “Stove, a hot-house for preserving Exotic Plants; also a Kitchen Term for a Sort of Furnace where they prepare Ragouts, &c.”

- Abercrombie, John, 1789, The Hot-House Gardener (1789: 44)[25]

- “For covering the hot-house glasses in severe weather in winter, sometimes light wooden shutters are used, or those of light wood frames and painted canvas.”

- M’Mahon, Bernard, 1806, The American Gardeners Calendar (1806: 84)[26]

- “HOT-HOUSES, or STOVES, are buildings erected for preserving such tender exotic plants, natives of the warmer and hottest regions, as will not live in the respective countries where they are introduced, without artificial warmth in winter. . .

- “These stove departments are generally constructed in an oblong manner, ranging in a straight line east and west, with the glass front and roof fully exposed to the south sun.” back up to History

- Gregory, G. (George), 1816, A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (1816: 2:n.p.)[27]

- “HOT-HOUSE, in gardening, an erection intended for the culture of the tender exotics of tropical climates. It is usually built lower than a greenhouse, with double flues, and a pit in the middle for tanner’s bark, in which, as in a kind of hot-bed, the pots containing the plants are to be plunged. A hot-house should be kept at a regular heat, seldom less than 70°; and when the weather becomes about 10° below that extremity, the fires may be left off. The tan should be renewed twice a year, in spring and autumn; and care must be taken not to plunge the plants in it till the heat is risen to a proper degree.

- “The ingenious Dr. Anderson, so well known for his labours in agriculture, has lately constructed a hot-house to be kept warm by air chiefly warmed by the heat of the sun. It is entirely of glass, and the upper part is a close chamber to contain the heated air, which is let into the house by a valve. In the winter the chamber is heated by a lamp, and the warm air is admitted in the same manner as that which is warmed by the sun. The house is also moveable; but for further details we must refer to the doctor’s Agricultural Recreations.”

- Abercrombie, John, with James Mean, 1817, Abercrombie’s Practical Gardener (1817: 586–87)[28]

- “The term Hot-house, and that of Forcing-house, are not indiscriminately applied to the same description of place by practical men in general; nor is this a distinction without a difference. A Hot-house may be considered as constructed to sustain plants which are too tender to live in the open air of the country in which it is employed:—a Forcing-house may be defined to be an artificial garden for vegetables which will grow in the open air, but its aid to obtain a crop sooner than the natural operation of the seasons will raise and mature one:—thus the former is permanent and more uniform, resembling the steady elevation of temperature which prevails in the regions nearest the line: that of the latter fluctuates farther from a common medium; but whether raised or reduced, it is equally directed to an imitation of nature’s course in some climate. The Forcing-house, however, is frequently so assimilated in its construction and economy to the Hot-house, on account of the culture requisite for plants of a mixed nature, that the difference vanishes.”

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826: 312–15, 322–23, 811)[29]

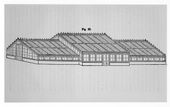

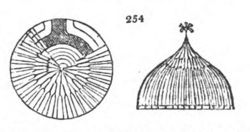

- “1595. The introduction and management of light is the most important point to attend to in the construction of hot-houses. . .

- “1602. The general form and appearance of roofs of hot-houses, was, till very lately, that of a glazed shed or lean-to; differing only in the display of lighter or heavier frame-work or sashes. But Sir George Mackenzie’s paper on this subject, and his plan and elevation of a semi-dome (Hort. Trans. vol. ii. p. 175.), have materially altered the opinion of scientific gardeners. . .

- “1603. Some forms of hot-houses on the curvilinear principle shall now be submitted, and afterwards some specimens of the forms in common use; for common forms, it is to be observed, are not recommended to be laid aside in cases where ordinary objects are to be attained in the easiest manner; and they are, besides the forms of roofs, the most convenient for pits, frames, and glass tents, as already exemplified in treating of these structures. . . [Fig. 15]

- “1640. Walls of some sort are necessary for almost every description of hot-house, for even those which are formed of glass on all sides are generally placed on a basis of masonry. But as by far the greater number are erected for culinary purposes, they are placed in the kitchen-garden, with the upper part of their roof leaning against a wall, which forms their northern side or boundary, and is commonly called the back wall, and the lower part resting on a low range of supports of iron or masonry, commonly called the front wall. . .

- “1647. The most general mode of heating hothouses is by fires and smoke-flues, and on a small scale, this will probably long remain so. Heat is the same material, however produced; and a given quantity of fuel will produce no more heat when burning under a boiler than when burning in a common furnace. Hence, with good air-tight flues, formed of well burnt bricks and tiles accurately cemented with lime-putty, and arranged so as the smoke and hot air may circulate freely, every thing in culture, as far as respects heat, may be perfectly accomplished. . .

- “6161. The hot-houses of floriculture are the frame, glass case, green-house, orangery, conservatory, dry-stove, the bark or moist stove, in the flower-garden, or pleasure-ground; and the pit and hot-bed in the reserve-garden. In the construction of all of these the great object is, or ought to be, the admission of light and the power of applying artificial heat with the least labor and expense.”

- Fessenden, Thomas Green, 1833, The New American Gardener (1833: 163)[30]

- “HOT-HOUSE.—'A hot-house is a building intended to form habitation for vegetables; either for such exotic plants as will not grow in the open air of the country where the building is erected, or for such indigenous and acclimated plants as it is desired to force or excite into a state of vegetation, or accelerate their maturation at an extraordinary season.

- “‘Such heat as is required, in addition to that of the sun, is most generally produced by the ignition of carbonaceous materials, which heat the air of the house,’ . . . Encyc. of Gardening.

- “Steam affords the most simple and effectual mode of heating hot-houses and indeed large bodies of air in any building, and is the most convenient carrier of heat, which human ingenuity has ever discovered or employed.—See Encyc. of Gardening, from p. 310 to pp. 333, 502, &c.”

- Buist, Robert, 1841, The American Flower Garden Directory (1841: 145, 148)[31]

- “ON THE CONSTRUCTION OF A HOTHOUSE. . .

- “Site and Aspect.—The house should stand on a situation naturally dry, and, if possible, sheltered from the north-west, and clear from all shade on the south, east, and west, so that the sun may at all times act effectually upon the house. The standard principle, as to aspect, is to set the front directly to the south. Any deviation from that point should incline to the east.

- “Dimensions.—The length may be from ten feet upward; but, if beyond forty feet, the number of fires and flues are multiplied. The medium width is from twelve to sixteen feet. . .

- “Bark Pit.—We consider such an erection in the centre of a hot-house a nuisance, and prefer a stage, which may be constructed according to taste. It should be made of the best Carolina pine, leaving a passage all round, to cause a free circulation of air.”

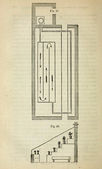

- Loudon, Jane, 1845, Gardening for Ladies (1845: 248–49)[32]

- “HOTHOUSES differ from greenhouses in being kept at a higher temperature, so as to suit tropical plants; and in having a flat bed for the principal part of the plants to stand on, instead of a sloping stage of shelves. This bed is commonly surrounded by a narrow brick wall, two or three feet high, and filled with tan in which the plants are plunged; but in some cases, instead of tan, or any other fermenting material, there is a cavity beneath the bed, in which flues or pipes of hot water are placed; and the surface of the bed is either covered with sand, or some other material, calculated to retain an equality of moisture, in which the pots are plunged in the same manner as in the tan.”

- Johnson, George William, 1847, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening (1847: 79, 203, 228–29, 270, 559)[33]

- “BARK STOVE, or Moist Stove, is a hot-house which, either by having a mass of fermenting matter, or an open reservoir of hot water within side, has its atmosphere constantly saturated with moisture, congenially with the habits of some tropical plants. It received the name of Bark Stove, because tanner’s bark was formerly a chief source of heat employed. (See Stove.) . . .

- “DRY STOVE is a hot-house devoted to the culture of such plants as require a high degree of heat, but a drier atmosphere than the tenants of the bark-stove. Consequently, fermenting materials and open tanks of hot-water are inadmissible; but the sources of heat are either steam or hot-water pipes, or flues. See Stove. . .

- “FLOWER POTS. . .

- “I cannot recommend an adoption of large pots, ensuring as they do such an immense sacrifice of room in the hot and green-houses. . . .

- “GREEN-HOUSE. This is a winter-residence for plants that cannot endure the cold of our winter, yet do not require either the high temperature or moist atmosphere of a stove [i e. hot-house]. . .

- “STOVES, as they are usually called in England, or hot-houses, as distinctive from greenhouses, are variously constructed in accordance with the habits of the plants for which they are intended.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, December 1848, “A Chapter on Green-Houses” (Horticulturist 3: 258)[34]

- “There are many of our readers who enjoy the luxury of green-houses, hot-houses, and conservatories,—large, beautifully constructed, heated with hot water pipes, paved with marble, and filled with every rare and beautiful exotic worth having, from the bird-like air plants of Guiana to the jewel-like Fuchsias of Mexico. They have taste, and much ‘money in their purses.’”

- Leuchars, Robert B., 1850, A Practical Treatise on the Construction, Heating, and Ventilation of Hothouses (1850: 192, 210-211)[35]

- "SECTION V.

- VARIOUS METHODS OF HEATING DESCRIBED IN DETAIL"

- "The heating of hot-houses, by any of the ordinary methods of warming these structures, has hitherto been attended with extravagant expense. . ."

- "Fig. 43 shows a house wherein provision is made for increasing the heating surface, when more than a very moderate degree of heat is required from the pipes. A box or tank, made of wood or zinc, is placed under the stage, and passes all round it on a level with the pipes. This tank is supplied by a branch pipe a, proceeding from the flow-pipe, and is provided with a tap at b, for shutting off and on the water when necessary. . ." [Fig. 16]

Images

Inscribed

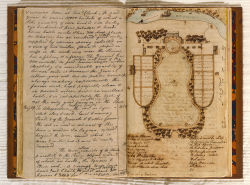

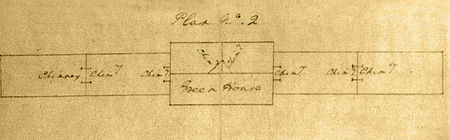

Samuel Vaughan, Sketch plan of Mount Vernon, June-September 1787. “15. Hot house” marked on the left side of the drawing.

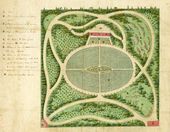

William Bartram, “Plan of the Ancient Chunky-Yard,” in “Observations on the Creek and Cherokee Indians” (1789), from Transactions of the American Ethnological Society (1853), vol. 3, part 1, 52, fig. 2. “B, a circular eminence. . . Upon this mound stands the Great Rotunda, Hot House, or Winter Council House of the present Creeks.”

Anonymous, Plan of the Harvard Botanic Garden, c. 1807. “E. Hot House” marked near the top of the plan.

J. C. Loudon, “The acuminated semi-globe” hot-house, in An Encyclopædia of Gardening (1826), 315, fig. 254.

J. C. Loudon, Culinary hot-houses placed in a range, in An Encyclopædia of Gardening (1826), 510, fig. 451.

J. C. Loudon, “General View of the Hot-houses, as seen across the American Garden,” Cheshunt Cottage, in The Gardener’s Magazine 15, no. 117 (December 1839): 646, fig. 161.

Associated

Jeremiah Paul, Robert Morris’ Seat on Schuylkill, July 20, 1794.

William Groombridge, View of Lemon Hill, c. 1800.

John Archibald Woodside, Lemon Hill, 1807.

William Satchwell Leney after Louis Simond, View of the botanic garden at Elgin in the vicinity of the City of New York, c. 1810.

Hugh Reinagle, Elgin Garden on Fifth Avenue, c. 1812.

J. C. Loudon, Plan of farmyard, garden offices and hot-houses at Cheshunt Cottage, in The Gardener’s Magazine 15, no. 117 (December 1839): 642, fig. 159.

Robert Mills, Alternative plan for the grounds of the National Institution, 1841.

Alfred Hoffy, View of Robert Buist’s City Nursery and Greenhouses, 1846.

George Washington, Plan for the greenhouse quarters at Mount Vernon, Plan No. 2, c. 1785.

Attributed

George Washington, Plan for the greenhouse quarters at Mount Vernon, Plan No. 1, c. 1785.

Anonymous (artist), George Hayward (lithographer), Vauxhall Garden 1803, 1856.

Notes

- ↑ Bernard M’Mahon, The American Gardener’s Calendar: Adapted to the Climates and Seasons of the United States. Containing a Complete Account of All the Work Necessary to Be Done. . . for Every Month of the Year (Philadelphia: Printed by B. Graves for the author, 1806), 78, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anne Yentsch, “The Calvert Orangery in Annapolis: A Horticultural Symbol of Power and Prestige in an Early Eighteenth-Century Community,” in William M. Kelso and Rachel Most, eds., Earth Patterns: Essays in Landscape Archaeology (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1990), 175, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jean de La Quintinie, “What sort of Culture is most proper for every particular Plant,” The Compleat Gard’ner, or Directions for cultivating and right ordering of fruit-gardens and kitchen gardens, trans. John Evelyn, 2 vols. (1693; repr., New York: Garland, 1982), 2: 193, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 John D. Norton and Susanne A. Schrage-Norton, “The Upper Garden at Mount Vernon Estate—Its Past, Present, and Future: A Reflection on 18th-Century Gardening. Phase II: The Complete Report” (Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association Library, 1985), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Karen Madsen, “William Hamilton’s Woodlands,” (paper presented for seminar in American Landscape, 1790–1900, instructed by E. McPeck, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University, 1988), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 William Bentley, The Diary of William Bentley, D.D., Pastor of the East Church, Salem, Massachusetts (Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1962), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Carl R. Lounsbury, ed., An Illustrated Glossary of Early Southern Architecture and Landscape (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Barbara Wells Sarudy, “Eighteenth-Century Gardens of the Chesapeake,” Journal of Garden History 9, no. 3 (July–September 1989): 104–59, view on Zotero.

- ↑ David Hosack, Catalogue of Plants Contained in the Botanic Garden at Elgin (New York: T. and Y. Swords, 1806), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Drayton, “The Diary of Charles Drayton I, 1806,” Drayton Papers, MS 0152, Drayton Hall, SC, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Therese O’Malley, “Art and Science in American Landscape Architecture: The National Mall, Washington, DC, 1791–1852” (PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1989), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 John Hebron Moore, “A View of Philadelphia in 1829: Selections from the Journal of B. L. C. Wailes of Natchez,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 78 (July 1954): 353–60, view on Zotero.

- ↑ James Boyd, A History of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1827–1927 (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1929), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Martha Ogle Forman, Plantation Life at Rose Hill: The Diaries of Martha Ogle Forman, 1814–1845 (Wilmington: Historical Society of Delaware, 1976), view on Zotero.

- ↑ James Thacher, “An Excursion on the Hudson. Letter II,” New England Farmer, and Horticultural Journal 9, no. 20 (December 3, 1830): 156–57, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Andrew Jackson Downing, “Notices on the State and Progress of Horticulture in the United States,” Magazine of Horticulture 3, no. 1 (January 1837): 1–10, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Mason Hovey, “Some Remarks upon Several Gardens and Nurseries, in Providence, Burlington, (N.J.) and Baltimore,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 5, no. 10 (October 1839): 361–76, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Nathaniel Parker Willis, American Scenery; or, Land, Lake and River Illustrations of Transatlantic Nature (London: G. Virtue, 1840), vol. 2, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Pamela Scott, ed., The Papers of Robert Mills (Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Resources, 1990), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Mason Hovey, “Notes Made during a Visit to New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington, and Intermediate Places, from August 8th to the 23rd, 1841,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 7, no. 10 (October 1841): 361–74, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Mason Hovey, “Notes Made during a Visit to New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington, and Intermediate Places, from August 8th to the 23rd, 1841,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 8, no. 4 (April 1842): 121–29, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Horticola [pseud.], “Notes on Gardens and Country Seats near Boston,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 7, no. 3 (March 1852): 126–28, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Ephraim Chambers, Cyclopaedia, or An Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences. . . , 5th ed., 2 vols. (London: D. Midwinter: 1741–43), vol. 1, view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Salmon, Palladio Londinensis, or The London Art of Building: In Three Parts. . . with Fifty-Four Copper Plates, to Which Is Annexed, The Builder’s Dictionary, ed. E. Hoppus, 6th ed. (London: Printed for C. Hitch et al., 1762), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Abercrombie, The Hot-House Gardener (London: J. Stockdale, 1789), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bernard M’Mahon, The American Gardener’s Calendar: Adapted to the Climates and Seasons of the United States. Containing a Complete Account of All the Work Necessary to Be Done. . . for Every Month of the Year (Philadelphia: Printed by B. Graves for the author, 1806), view on Zotero.

- ↑ George Gregory, A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences, 1st American ed., 3 vols. (Philadelphia: Isaac Peirce, 1816), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Abercrombie, Abercrombie’s Practical Gardener Or, Improved System of Modern Horticulture (London: T. Cadell and W. Davies, 1817), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, 4th ed. (London: Longman et al., 1826), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Fessenden, The New American Gardener, 7th ed. (Boston: Russell, Odiorne, 1833), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Robert Buist, The American Flower Garden Directory, 2nd ed. (Philadelphia: Carey and Hart, 1841), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jane Loudon, Gardening for Ladies; and Companion to the Flower-Garden, ed. A. J. Downing (New York: Wiley & Putnam, 1845), view on Zotero.

- ↑ George William Johnson, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening, ed. David Landreth (Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1847), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Andrew Jackson Downing, “A Chapter on Green-Houses,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 3, no. 6 (December 1848): 257–62, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Robert B. Leuchars, A Practical Treatise on the Construction, Heating, and Ventilation of Hothouses, (New York: O. Judd, 1850), view on Zotero.