Kitchen garden

(Kitchen-garden)

History

In New England’s Prospect (1634), William Wood described the Massachusetts Bay Colony geography “as it stands to our new-come English planters, and to the old native inhabitants.” Most important to the recent settlers was the suitability of the land for growing food in what was commonly called a kitchen garden. The kitchen garden provided vegetables, herbs, and often fruit for a family’s table. It was an essential part of a household’s subsistence base, particularly given the difficulty of transporting fresh produce long distances in the absence of refrigeration and a developed road system. Unlike agricultural fields, the kitchen garden was smaller in scale, contained a variety of crops, and was generally enclosed and located near the dwelling house.

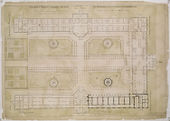

As European settlement expanded, travelers throughout the colonies recorded well-organized kitchen gardens as a sign of the prosperity of a region. As markets grew and produce became more widely available, the importance of kitchen gardens diminished, at least for households in towns. Mary M. Ambler (1770) commented that in Baltimore, “People depend on the Market for their Stuff for there is not more than Seven Gardens in the Whole Town.”[1] Living in Philadelphia, Benjamin Franklin noted that there existed such “well-furnished plentiful markets” that he converted his kitchen garden into grass plots and gravel walks with trees and flowering shrubs, rather than for the cultivation of peas and cauliflowers.[2] Kitchen gardens were essential, however, for those without access to markets.[3] They were not only in domestic but also institutional layouts, such as that mentioned in the description of the Friends Asylum for the Insane, near Frankford, Pennsylvania, and seen in the design for the Marine Asylum in Washington, DC [Fig. 1]. A kitchen garden primarily provided food and diversion for the asylum residents. In addition, as Thomas S. Kirkbride noted for the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane in Philadelphia, the three-and-a-half-acre vegetable garden was to be “large enough to furnish all of that description of supplies that may be required for the institution, and may occasionally be made profitable from sales of the excess.”[4]

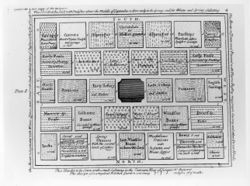

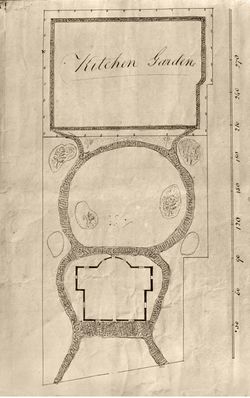

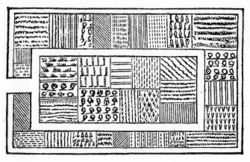

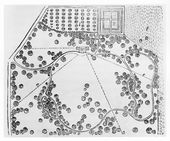

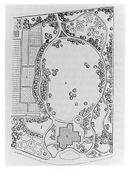

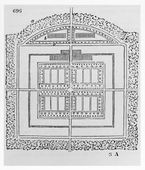

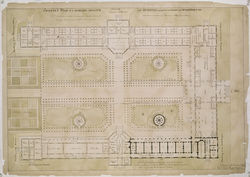

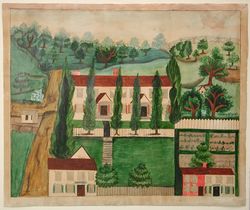

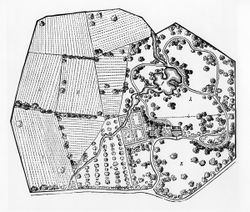

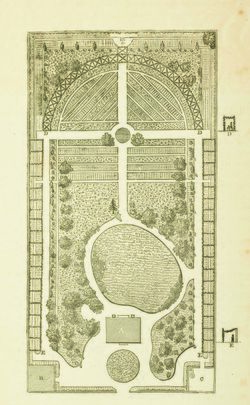

Garden treatises described in detail the layout and care of kitchen gardens and were remarkably consistent in their advice. The size of the kitchen garden depended upon the needs of the household, and several treatises mention a preference for regular shapes, such as a square or rectangle. All citations emphasized the need to enclose a kitchen garden with a wall or a fence. These barriers created sheltered environments and also deterred potential intruders. Within the confines of the garden, treatises also suggest laying out beds, squares, or quarters, dividing them by walks, and creating borders along the perimeters. Many texts suggest planting smaller varieties of fruit trees, either espaliered along the wall or fence or planted in borders. These trees not only bore fruit earlier than their less-protected counterparts, but also, as mentioned by Bernard M’Mahon (1806), their shelter created microclimates for the growth of smaller plants beneath them. While treatises often offered a variety of designs for the arrangement of plant material within the kitchen garden from the complex [Fig. 2] to the relatively simple [Fig. 3], American kitchen gardens appear to have been executed in fairly modest form, even at the most elaborate estates [Figs. 4 and 5].

The placement of a kitchen garden within the larger landscape of the farm or estate was a point of both practical and aesthetic debate in treatise citations, and, judging from the collected images [Figs. 6 and 7] and texts, a considerable variety of plans were adopted throughout the colonies. Some treatises suggested that the convenience of having the kitchen garden near the house for ease of tending and harvesting was balanced with the desire to remove the less attractive sights and smells of a manured garden, and crops such as cabbages and onions. Others extolled the convenience of placing the kitchen garden near the greenhouse (if one existed), or near the stables and barns for easy conveyance of dung. On a more aesthetic question, treatise writers disagreed about the relationship of the kitchen garden to more ornamental areas of an estate. Authors ranging from John Parkinson (1629) to J. C. Loudon (1826), George William Johnson (1847), and A. J. Downing (1849) in the 19th century advocated separating or at least screening the kitchen garden from other areas of the pleasure ground. Ephraim Chambers (1741) noted that kitchen and fruit gardens were for “service” while flower gardens were to be placed conspicuously “for pleasure, and ornament.” Downing's plan of a suburban villa residence offered one solution of screening the kitchen garden from the lawn by “thick groups of evergreen and deciduous trees.”[5] In garden periodicals and treatises of the 1840s, the kitchen garden saw a resurgence as an element of newly marketed plans for suburban domestic landscapes.

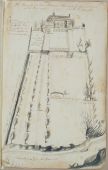

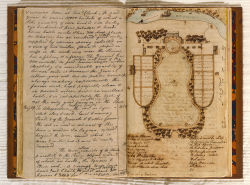

Other writers and practitioners emphasized the integration of the kitchen garden with other parts of the landscape. This general concept, first described by Stephen Switzer (1718) in Ichnographia rustica, more often was referred to as an “ornamental farm” (see Ferme ornée). Thomas Jefferson advised landowners to “lay off lots for the minor articles of husbandry. . . disposing them into a ferme ornée by interspersing occasionally the attributes of a garden.”[6] This aesthetic was exemplified at two of the colonies’ most famous sites, Monticello and Mount Vernon. In each instance, the kitchen garden was visually screened from the views from the house, but was nonetheless incorporated into the overall landscape design. For example, Vaughan’s Mount Vernon plan of 1787 [Fig. 8] depicted the kitchen and flower gardens symmetrically balanced, but the placement of the kitchen on the southern or “lower” side meant that it was visually much less prominent than the northern flower garden and its corresponding elaborate greenhouse. At Monticello, Jefferson's plans (most of which were never executed) called for interspersing pavilions, temples, a grotto, grove, flower beds, and other “ornamental” features throughout the grounds and linking them with walks and roundabouts. Jefferson (1804), however, admitted that “after all, the kitchen garden is not the place for ornaments of this kind, bowers and treillages suit that better.” The 19th-century legacy of this aesthetic of integration may be seen in plans such as that published by Downing in A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849) for the ferme ornée [Fig. 9].

—Elizabeth Kryder-Reid

Texts

Usage

- Byrd, William, II, April 2, 1721, describing Westover, seat of William Byrd II, on the James River, VA (1958: 513)[7]

- “. . . took a walk in the orchard and kitchen garden and ordered Captain C-p man some cider, who came to see the garden.”

- Anonymous, January 30, 1749, describing a plantation for sale near Charleston, SC (South Carolina Gazette)

- “TO BE SOLD at Public Vendue. . . his plantations on the Ashley-River and Wappoo-Creek. . . [with] a very large garden both for pleasure and profit. . . [and] a great deal of fine asparagus, and all kinds of kitchen-garden stuff.”

- Kalm, Pehr, June 23, 1749, describing the vicinity of Albany, NY (1937: 1:355–56)[8]

- “The farms were commonly built close to the river, on the hills. Each house had a little kitchen garden and a still lesser orchard. Some farms, however, had large gardens. The kitchen gardens yielded several kinds of pumpkins, watermelon and kidney beans. This year the trees had few or no apples on account of the frosty nights which had come in May and the drought which had continued throughout this summer.”

- Anonymous, January 28, 1771, describing Vauxhall Garden, New York, NY (New York Gazette, and Weekly Mercury)

- “To be sold at private Sale, the commodious house and large gardens, in the out ward of this city, known by the name of VAUXHALL; the situation extremely pleasant, having a very extensive view both up and down the North River. . . there are 36 lots and a half of ground laid out to great advantage in a pleasure, and kitchen garden, well stock’d with fruit and other trees, vegetables, &c. and several summer houses which occasionally may be removed; the whole in extreme good order and repair, well fenced in, very fit for a large family, or to entertain the gentry, &c. as a public garden, &c. The premises are on lease from Trinity Church, sixty one years of which are yet to come.”

- Carroll, Charles (of Annapolis), 1775, in a letter to his son, Charles Carroll (of Carrollton), advising him on his garden (Maryland Historical Society, A. E. Carroll Papers)

- “Examine the Gardiner strictly as to. . . in what Branch He had been Chiefly employed, ye Kitchen or Flower 'Garden'.”

- Hazard, Ebenezer, May 31, 1777, describing the College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA (quoted in Shelley 1954: 405)[9]

- “The Wings are on the West Front, between them is a covered Parade, which reaches from the one to the other. . . opposite to this Parade is a Court Yard & a large Kitchen Garden.”

- Vaughan, Samuel, 1787, describing Mount Vernon, plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (quoted in Norton and Schrage-Norton 1985: 142)[10]

- "Before the front of the house. . . there are lawns, surrounded with gravel walks 19 feet wide. with trees on each side the larger, for shade. outside the walks trees & shrubberies. Parralel [sic] to each exterior side a Kitchen Gardens. with a stately hot house on one side."

- Bentley, William, October 22, 1790, describing the Elias Hasket Derby Farm, Peabody, MA (1962: 1:180)[11]

- “[231] 22. . . Beyond the Garden is a Spot as large as the Garden which would form an admirable orchard now improved as a Kitchen garden, & has not an ill effect in its present state."

- Anonymous, May 31, 1791, describing a gardener for hire (Maryland Journal, and Baltimore Advertiser)

- “A Gardener, (A young Man) of great Knowledge and Experience, acquired in celebrated Gardens, in England and Ireland, would undertake to serve any Gentleman in That Capacity, either in a Kitchen or Flower Garden, in the most faithful Manner, and on Terms the most moderate.”

- La Rochefoucauld Liancourt, François Alexandre-Frédéric, duc de, 1795–97, describing a farm in Springmill, PA (1800: 1:19)[12]

- “No kitchen-garden can be in better order; the vine-props are already fixed in the ground.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, 1804, describing Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, VA (quoted in Nichols and Griswold 1978: 110–11)[13]

- “At the Rocks’. . . a turning Tuscan temple. . . proportions of Pantheon, . . . at the Point, . . . build Demosthenes’s lantern. . . The kitchen garden is not the place for ornaments of this kind. bowers and treillages suit that better, & these temples will be better disposed in the pleasure grounds.”

- Drayton, Charles, November 2, 1806, describing The Woodlands, seat of William Hamilton, near Philadelphia, PA (1806: 58)[14]

- “The kitchen garden & Hort. yard/Orchyard, which I did not see, are, I suppose behind the Stables, & adjacent.”

- Boudinot, Elias, 1809, describing the garden of Stephen Higginson, Brookline, MA (quoted in Emmet 1996: 9)[15]

- “The grounds around [the house] laid out much in the English style. . . The Kitchen garden at a distance, & thro’ Which Walks wind so as to extend them about a quarter of a mile, all bordered with Grapes & Flowers.”

- Waln, Robert Jr., 1825, describing the Friends Asylum for the Insane, near Frankford, PA (1825: 231–32)[16]

- “The flower garden, extending from the vestibule to a dark green hedge of cedar, which separates it from the kitchen garden, offers a rich repast to the eye. . . .

- “The kitchen garden comprises about one and an half acres of ground, and, under the care of a skilful horticulturalist, affords abundance of vegetables for the use of the patients. From this source alone, they are plentifully supplied, at the proper seasons, with a great variety of wholesome vegetables. Cauliflowers, and early vegetables of various kinds, are successfully reared in hot-beds; and a sufficient quantity of tobacco for the restricted consumption of the convalescent patients, is also grown on the premises. Salutary herbs, and medicinal plants, so essential to the invalid, are cultivated in large quantities.”

- Committee of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1830, describing a country residence near Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Boyd 1929: 439)[17]

- “Nothing on these grounds pleased us more than the perfect order of the kitchen garden. It contains about two acres, and is indeed, a picture of culinary horticulture. There are 4 walks in the length and 9 in the breadth; all intersecting at right angles, and making 24 divisions, besides borders; and these divisions are cropt with vegetables in the finest order: each division having its own cropt (not intermixed as we see in most gardens), which is through every stage attended with the utmost regularity. The walks gravelled and edged with boxwood neatly clipped; and all exhibiting a lovely specimen of the art.

- “A half acre of other ground is devoted to flowers and decorative shrubs. On the whole we can safely assert that there is not a finer kept, or better regulated kitchen garden on this continent. Indeed it will bear a comparison with European gardens of the highest cultivation, according to its size. And what is exceedingly gratifying, is, that the gardener is a native American, and has superintended the place 14 years; which shows at once capacity and constancy.”

- Martineau, Harriet, 1834, describing Hyde Park, seat of Dr. David Hosack, on the Hudson River, NY (1838: 1:55)[18]

- “We drove round his kitchen-garden too, where he had taken pains to grow every kind of vegetable which will flourish in that climate.”

- Downing, A. J., 1849, describing the grounds of Riverside Villa, Burlington, NJ (1849; repr., 1991: 117–18)[19]

- “The house, a, stands quite near the bank of the river, while one front commands fine water views, and the other looks into the lawn or pleasure grounds, b. On one side of the area is the kitchen garden, c, separated and concealed from the lawn by thick groups of evergreen and deciduous trees.” [Fig. 10]

- Downing, A. J., 1849, describing Cheshunt Cottage, property of William Harrison, near London, England (1849; repr., 1991: 517)[19]

- “The masses of trees and shrubs are chiefly on the mount near the lake, and along the margin which shuts out the kitchen-garden; and in these places they are planted in the gardenesque manner, so as to produce irregular groups of trees, with masses of evergreen and deciduous shrubs as undergrowth, intersected by glades of turf. They are scattered over the general surface of the lawn, so as to produce a continually varying effect, as viewed from the walks; and so as to disguise the boundary, and prevent the eye from seeing from one extremity of the grounds to the other, and thus ascertain their extent.”

- Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), December 1849, describing Oatlands, residence of D. F. Manice, Hempstead, NY (Magazine of Horticulture 15: 529)[20]

- “The house is a handsome building, in a kind of castellated gothic, standing about fifty feet from the road, with the conservatory and hothouse, and flower garden on the left,—the kitchen garden and forcing-houses on the right,—and the lawn and pleasure ground, in the rear of the house, separating it from the park.”

- Leuchars, R. B., February 1850, “Notes on Gardens and Gardening in the neighborhood of Boston,” describing Bellmont Place, residence of John Perkins Cushing, Watertown, MA (Magazine of Horticulture 16: 50)[21]

- “The inclosed space, of about two acres, forms the kitchen garden, which is finely laid out, trellised and planted with the finer sorts of pears, peaches, &c. These latter were on trellises, and protected with spruce branches, from the frost, or rather from the hot sun that succeeds it.”

Citations

- Parkinson, John, 1629, Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris (1629: 461)[22]

- “As before I shewed you that the beautie of any worthy house is much the more commended for the pleasant situation of the garden of flowers, or of pleasure, to be in the sight and full prospect of all the chiefe and choisest roomes of the house; so contrariwise, your herbe [or kitchen] garden should bee on the one or other side of the house, and those best and choyse roomes: for the many different sents that arise from the herbes, as Cabbages, Onions, &c. are scarce well pleasing to perfume the lodgings of any house; and the many overtures and breaches as it were of many of the beds thereof, which must necessarily bee, are also as little pleasant to the sight.”

- Wood, William, 1634, “Of the herbs, Fruits, Woods, Waters, and Minerals,” in New England’s Prospect (1634; repr., 1977: 36, 58)[23]

- “The ground affords very good kitchen gardens for turnips, parsnips, carrots, radishes, and pumpions, muskmellon, isquoterquashes, cucumbers, onions, and whatsoever grows well in England grows as well there, many things being better and larger. . . [in Dorchester] very good arable grounds and hay ground, fair cornfields and pleasant gardens, with kitchen gardens.”

- La Quintinie, Jean de, 1693, The Compleat Gard’ner (1693; repr., 1982: n.p.)[24]

- “Kitchen-Gardens are chiefly for Kitchen and Edible Plants.

- “Potagery, is a Term signifying all sorts of Herbs or Kitchen-plants, and all that concerns them, considered in general.”

- Chambers, Ephraim, 1741, Cyclopaedia (1741: 1:n.p.)[25]

- “GARDEN. . .

- “Gardens are distinguished into flower-gardens, fruit-gardens, and kitchen-gardens: the first for pleasure, and ornament; and therefore placed in the most conspicuous parts: the two latter for service; and therefore made in by-places.”

- Miller, Philip, 1754, The Gardeners Dictionary (1754; repr., 1969: 724, 726–27)[26]

- “KITCHEN-GARDEN: The kitchen-garden should always be situated on one Side of the House, so as not to appear in Sight; but must be placed near the Stables, for the Conveniency of Dung. . .

- “As to the Figure of the Ground, that is of no great Moment, since in Distribution of the Quarters all Irregularities may be hid; tho’, if you are at full Liberty, an exact Square, or an Oblong, is preferable to any other Figure. . .

- “Then you should proceed to dividing the Ground out into Quarters, which must be proportion’d to the Largeness of the Garden; but I would advise, never to make them too small, whereby your Ground will be lost in Walks; and the Quarters being inclosed by Espaliers of Fruit-trees, the Plants therein will draw up slender, and never arrive to half the Size as they would do in a more open Exposure.

- “The Walks of this Garden should be also proportion’d to the Size of the Ground, which in a small Garden should be six Feet, but in a large one ten; and on each Side of the Walk should be allow’d a Border three or four Feet wide between the Espalier and the Walk, whereby the Distance between the Espaliers will be greater, and the Borders being kept constantly work’d and manur’d, will be of great Advantage to the Roots of the Trees; and in these Borders may be sown some small Sallad, or any other Herbs, which do not continue long, or root deep; so that the Ground will not be lost. . .

- “The best Figure for the Quarters to be disposed into, is a Square, or an Oblong, where the Ground is adapted to such a Figure; otherwise they may be triangular, or of any other Shape, which will be most advantageous to the Ground.”

- Johnson, Samuel, 1755, A Dictionary of the English Language (1755: 1:n.p.)[27]

- “KI’TCHENGARDEN. n.s. [kitchen and garden.] Garden in which esculent plants are produced.”

- Bradley, Richard, 1757, A General Treatise of Agriculture, both Philosophical and Practical (quoted in Dillon 1987b: 135)[28]

- “Rule for methodizing and assorting a parcel of ground containing 60 rods, for the use of a family of seven or eight persons, or for providing a kitchen-garden with necessaries for twenty or thirty in family.”

- Miller, Philip, 1759, The Gardeners Dictionary (1759: n.p.)[26]

- “Therefore, before the general Plan of the Pleasure garden is settled, a proper Piece of Ground should be chosen for this Purpose, and the plan so adapted, as that the kitchen garden may not be offensive to the sight, which may be effected by proper Plantations of Shrubs to screen the walls; and through these Shrubts may be continued some winding walks, which will have as good an effect as those which are now commonly made in gardens for Pleasure only. In the choice of the Situation, if it does not obstruct the views of better objects, or shut out any material Prospect, there can be no Objection to placing it at a reasonable distance from the house or offices.”

- Mawe, Thomas, and John Abercrombie, 1778, The Universal Gardener and Botanist (1778: n.p.)[29]

- “KITCHEN-GARDEN, a principal district of garden-ground allotted for the culture of all kinds of esculent herbs and roots for culinary purposes, &c.

- “A Kitchen-garden may be said to be the most useful and consequential part of gardening; since its products plentifully supply our tables, with the necessary support of life. . . This garden is not only useful for raising all sorts of esculent roots and herbs, but also all the choicer sorts of tree and shrub-fruits, &c. both on espaliers, wall-trees, and standards. . .

- “As to the place of disposition of this garden respecting the other districts, if it is designed principally as a Kitchen and fruit-garden, distinct from the other parts, and there is room for choice of situation, it should generally be placed detached entirely from the pleasure-ground; also as much out of view of the habitation as possible, at some reasonable distance, either behind it, or towards either side thereof, so as its walls or other fences may not obstruct any desirable prospect either of the pleasure-garden, park, fields, or the adjacent country. . .

- “But as in many places they are limited to a moderate compass of ground, in others have scope enough, and require but a moderate extent of garden; that in either case, have often the Kitchen, fruit, and pleasure-garden all in one; having the principal walks spacious, and the borders next them of considerable breadth; the back part of them planted with a range of espalier fruit-trees, surrounding the quarters; the front with flowers and small shrubs; and the inner quarters for the growth of the Kitchen-vegetables, &c. . .

- “The ground must be divided into compartments for regularity and convenience. A border must be carried all round the boundry-walls, not less than four, but if six, eight or ten feet wide, the better, for the benefit of the wall-trees. . . next to this border a walk should be continued also all round the garden, of due width. . . proceed to divide the interior parts into two, four, or more principal divisions and walks, if its extent be large.”

- Deane, Samuel, 1790, The New-England Farmer (1790: 110–11, 155–56)[30]

- “GARDEN. . .

- “I consider the kitchen garden as of very considerable importance, as pot-herbs, sallads, and roots of various kinds, are useful in housekeeping. Having a plenty of them at hand, a family will not be so likely to run into the errour, which is too common in this country, of eating flesh in too great a proportion for health. Farmers, as well as others, should have kitchen-gardens: And they need not grudge the labour of tending them, which may be done at odd intervals of time, which may otherwise chance to be consumed in needless loitering. . .

- “KITCHEN-GARDEN, a garden to produce vegetables for the kitchen. . .

- “I cannot approve of the quantity of land he [Mr. Miller] proposes to be laid out for a garden. Four or five acres I should think three or four times too much for almost any person in this country. Half an acre will be sufficient for almost any family, unless we except those who have independent fortunes.”

- Marshall, Charles, 1799, An Introduction to the Knowledge and Practice of Gardening (1799: 1:42)[31]

- “the kitchen garden should be adorned with a sprinkling of the more ordinary decorations, to skirt the quarters, which should be chiefly those of the most powerful sweet scents.”

- Forsyth, William, 1802, A Treatise on the Culture and Management of Fruit Trees (1802: 11, 150–51)[32]

- “If in the kitchen garden for Standards, I would always recommend the planting of Dwarfs. . . If the garden is laid out with crosswalks, or foot-paths, about three feet wide, make the borders six feet broad, and plant the trees in the middle of them. . .

- “Walls of kitchen gardens should be from ten to fourteen feet high. . .

- “When bricks can be had, I would advise never to build garden walls of stone; as it is by no means so favourable to the ripening of fruit as brick. When a kitchen garden contains four acres, or upwards, it may be intersected by two or more cross walls, which will greatly augment the quantity of fruit, and also keep the garden warm and shelter it greatly from high winds.”

- Repton, Humphry, 1803, Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1803: 127, 181)[33]

- “. . . the kitchen garden. . . might easily be concealed from the park by a shrubbery kept low. . .

- “The many interesting circumstances that lead us into a kitchen garden, the many inconveniences which I have witnessed from the removal of old gardens to a distance, and the many instances in which I have been desired to bring them back to their original situations, have led me to conclude that a kitchen garden cannot be too near, if it be not seen from the house.”

- M’Mahon, Bernard, 1806, The American Gardener’s Calendar (1806: 16)[34]

- “Espaliers. . . are commonly arranged in a single row in the borders, round the boundaries of the principal divisions of the kitchen-garden; there, serving a double or treble purpose, both profitable, useful, and ornamental. They produce large fine fruit plentifully, without taking up much room, and being in a close range, hedge-like; they in some degree shelter the esculent crops in the quarters; and having borders immediately under them each side, afford different aspects for different plants, and also they afford shelter in winter, forwardness to their south-border crops in spring, and shade in summer.”

- Gregory, G. (George), 1816, A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (1816: 1:n.p.)[35]

- “GARDENING. . .

- “It is also fashionable to make a separation between the pleasure and the kitchen garden. This may indeed preserve the few shrivelled fruit which the latter, on a diminutive scale, is capable of affording, from the hands of rapacious visitors; but the range of the proprietor becomes by this appointment most deplorably limited and diminished; and the vegetables will want what alone can render them fine and flourishing, the free circulation of air.”

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826: 309, 451, 455–58, 464–65, 1020)[36]

- “1582. Of fixed structures, the brick wall, both as a fence, and retainer of heat, may be reckoned essential to every kitchen-garden; and in many cases the mode of building them hollow may be advantageously adopted. . .

- “2355. To unite the agreeable with the useful is an object common to all the departments of gardening. The kitchen-garden, the orchard, the nursery, and the forest, are all intended as scenes of recreation and visual enjoyment, as well as of useful culture; and enjoyment is the avowed object of the flower-garden, shrubbery, and pleasure-ground. . .

- “2382. The situation of the kitchen-garden, considered artificially or relatively to the other parts of a residence, should be as near the mansion and the stable-offices, as is consistent with beauty, convenience, and other arrangements. Nicol observes, ‘In a great place, the kitchen-garden should be so situated as to be convenient, and, at the same time, be concealed from the house. . .’

- “2383. Sometimes we find the kitchen-garden placed immediately in front of the house, which Nicol ‘considers the most awkward situation of any. . . Generally speaking, it should be placed in the rear or flank of the house, by which means the lawn may not be broken and rendered unshapely where it is required to be most complete. The necessary traffic with this garden, if placed in front, is always offensive. . .’

- “2388. Main entrance to the garden. Whatever be the situation of a kitchen-garden, whether in reference to the mansion or the variations of the surface, it is an important object to have the main entrance on the south side, and next to that, on the east or west. The object of this is to produce a favorable first impression on the spectator, by his viewing the highest and best wall (that on the north side) in front; and which is of still greater consequence, all the hot-houses, pits, and frames in that direction. . .

- “2389. Bird’s-eye view of the garden. When the grounds of a residence are much varied, the general view of the kitchen-garden will unavoidably be looked down on or up to from some of the walks or drives, or from open glades in the lawn or park. Some arrangement will therefore be requisite to place the garden, or so to dispose of plantations that only favorable views can be obtained of its area. To get a bird’s-eye view of it from the north, or from a point in a line with the north wall, will have as bad an effect as the view of its north elevation, in which all its ‘baser parts’ are rendered conspicuous. . .

- “2396. The extent of the kitchen-garden must be regulated by that of the place, of the family, and of their style of living. In general, it may be observed, that few country-seats have less than an acre, or more than twelve acres in regular cultivation as kitchen-garden, exclusive of the orchard and flower-garden. From one and a half to five acres may be considered as the common quantities enclosed by walls. . .

- “2401. The kitchen-garden should be sheltered by plantations; but should by no means be shaded, or be crowded by them. If walled round, it should be open and free on all sides, or at least to the south-east and west, that the walls may be clothed with fruit-trees on both sides. . .

- “2431. In regard to form, almost all the authors above quoted [London, Wise, Evelyn, Hitt, Lawrence] agree in recommending a square. . . or oblong, as the most convenient for a [kitchen] garden; but Abercrombie proposes a long octagon, in common language, an oblong with the angles cut off. . .

- “2436. Walls are built round a garden chiefly for the production of fruits. A kitchen-garden, Nicol observes, considered merely as such, may be as completely fenced and sheltered by hedges as by walls, as indeed they were in former times, and examples of that mode of fencing are still to be met with. But in order to obtain the finer fruits, it becomes necessary to build walls, or to erect pales and railings. . .

- “7260. The kitchen-garden should be placed near to, and connected with the flower-garden, with concealed entrances and roads leading to the domestic offices for culinary purposes, and to the stables and farm-buildings for manure.”

- Dearborn, H. A. S., September 19, 1829, An Address, Delivered Before the Massachusetts Horticultural Society (1833: 16–17)[37]

- “The natural divisions of Horticulture are the Kitchen Garden, Seminary, Nursery, Fruit Trees and Vines, Flowers and Green Houses, the Botanical and Medical Garden, and Landscape, or Picturesque Gardening.

- “The Kitchen Garden is an indispensable appendage to every rural establishment, from the stately mansion of the wealthy, to the log hut of the adventurous pioneer, on the borders of the wilderness. In its rudest and most simple form, it is the nucleus, and miniature sample of all others, having small compartments of the products of each, which are gradually extended, until the whole estate combines those infinitely various characteristics, and assumes that imposing aspect, which constitutes what is graphically called the picturesque.”

- Anonymous, October 9, 1829, “Gardens” (New England Farmer 8: 92)[38]

- “People in general are too inattentive to that part of domestic economy which is denominated gardening. We do not mean by this term, any of the higher branches of this useful, as well as ornamental art, but choose to confine our remarks to the simple subject of kitchen gardens.

- “Within our own observation, these have been unwisely and unaccountably neglected by the agricultural community. That which might be easily made the most productive of profit, as well as luxury and comfort of any part of a farm, is too often the most neglected, and the least profitable. . .

- “We have said nothing of flowers and ornamental shrubs, because we address these remarks to practical and laboring men. These are indeed matters of luxury, and when they are properly cultivated, evince a fine taste, and deservedly attract the attention and admiration of those who witness them. But the cultivation of these have nothing to do with making a useful kitchen garden, and it is to this, we repeat, we confine these observations.”

- Bridgeman, Thomas, 1832, The Young Gardener’s Assistant (1832: 1–2)[39]

- “. . . some important matters essential to the good management of a Kitchen Garden. . .

- “To this end, he [the gardener] may form a border round the whole garden, from five to ten feet wide, according to the size of the piece of land; next to this border, a walk may be made from three to six feet wide; the centre part of the garden may be divided into squares, on the sides of which a border may be laid out three or four feet wide, in which the various flowering plants may be raised, unless a separate flower garden is intended. The centre beds, may be planted with all the various kinds of vegetables as well as Gooseberries, Currants, Raspberries, Strawberries, &c. The outside borders facing the East, South and West, will be useful for raising the earliest fruits and vegetables, and the North border being shady and cool, will serve for raising, and pricking out such young plants, slips and cuttings as require to be screened from the intense heat of the sun.”

- Johnson, George William, 1847, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening (1847: 96, 208, 228, 302–3, 334–35)[40]

- “BORDER. . .

- “1. Fruit-borders.—Next to the wall should be a path three feet wide, for the convenience of pruning and gathering. Next to this path should be the border, eight or nine feet wide; and then the broad walk, which should always encompass the main compartments of the kitchen garden. . .

- “EDGING. This for the kitchen-garden and all other places where neatness, not ornament, is the object, may consist of useful herbs, the strawberry &c. . .

- “FLOWER GARDEN. . .

- “it is usual to arrange it so that the kitchen garden is immediately beyond it. . . A very common proportion for a small cottage is, the flower garden being one-fourth the size of the kitchen garden.”

- “[HORTICULTURE. . .]

- “The kitchen garden is an indispensable appendage to every rural establishment. In its simplest form, it is the nucleus of all others. Containing small compartments for the culture of esculent vegetables, fruits and ornamental plants, these may be gradually extended, until the whole estate assumes the imposing aspect of picturesque or landscape scenery. . . “ KITCHEN GARDEN.

- “Situation of the Kitchen Garden.—In selecting the site, and in erecting the inclosures, as well as in the after preparation of the soil, the ingenuity and science of the horticulturist are essentially requisite. He will be called upon to rectify the defects and to improve the advantages which nature affords; for it is very seldom that the natural situation of a mansion, or the plan of the grounds, allows him to construct it in the most appropriate spot.

- “A gentle declination towards the south, with a point to the east, is the most favourable aspect; to the north-east the least so: in short, any point to the south is to be preferred to one verging towards the north. A high wall should inclose it to the north and east, gradually lowering to the south and west. If, however, a plantation or building on the east side, at some distance, shelter it from the piercing winds, which blow from that quarter, and yet are at such a distance as not to intercept the rays of the rising sun, it is much to be preferred to heightening the wall. It is a still greater desideratum to have a similar shelter, or that of a hill on the south-west and north-west points. The garden is best situated at a moderate elevation; the summit of a hill, or the bottom of a valley, is equally to be avoided. It is a fact not very difficult of explanation, that low lying ones are the most liable to suffer from blights and severe frosts; those much above the level of the sea are obviously most exposed to inclement winds.

- “Size of the Kitchen Garden.—To determine the appropriate size of a kitchen garden is impossible. It ought to be proportionate to the size of the family, their partiality for vegetables, and the fertility of the soil.

- “It may serve as some criterion to state, that the management of a kitchen garden occupying the space of an acre, affords ample employment for a gardener, who will also require an assistant at the busiest period of the year. In general, a family of four persons, exclusive of servants, requires a full rood of open kitchen garden.

- “Plan of the Kitchen Garden.—In forming the ground plan of a kitchen garden, utility is the main object. The form and aspect represented in the accompanying sketch . . . are, perhaps, as unobjectionable as any, since none of the walls face the north, and consequently the best aspects are obtained for the trees. A narrow path two feet wide should extend round, adjoining the wall, and then a border about ten feet, the widest on those broad sides that face the south, which not only is beneficial to the trees, but convenient for raising early crops, &c. Next to this should be walk five feet in width, likewise extending round the area. [Fig. 11]

- “Respecting the inclosure of the kitchen garden, see Hedges and Walls.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1849, “Design for a Suburban Garden” (Horticulturist 3: 380)[41]

- “The whole garden is surrounded by a wall, which is covered with fruit trees trained. . .

- “At the end of this wall, we come to the semicircular Italian arbor, D. This arbor, which is very light and pleasing in effect, is constructed of slender posts, rising 8 or 9 feet above the surface, from the tops of which strong transverse strips are nailed, as shown in the plan. . .

- “Beyond this arbor, and at the termination of the central walk, is a vase, rustic basket, or other ornamental object, e. The semi-circle, embraced within the arbor, is a space laid with regular beds. This is devoted to kitchen garden crops, as is also all the outside border behind it. The other borders (under the vines, E,) may be cropped with strawberries, or lettuces, and other small culinary vevetables [sic] with a narrow grouping of flowers near the walk or not, as the taste of the owner may dictate. The small trees, planted in rows on the border, between the walk, E, and the ornamental lawn, are dwarf pears and apples.” [Fig. 12]

- Kidd, George, April 1849, “A Hint on Kitchen Gardens” (Horticulturist 3: 471)[42]

- “It is desirable, in many respects, that the kitchen-garden should be near the barn-yard, and so arranged that the bulk of the work may be performed with the plough.”

Images

Inscribed

Batty Langley, The Design of an Elegant Kitchen Garden Contain’g ARP 1.2.20. Including Walks, in New Principles of Gardening (1728), pl. V.

Batty Langley, “Design of a Small Garden Situated in a Park,” in New Principles of Gardening (1728), pl. XII.

John or William Bartram, "A Draught of John Bartram’s House and Garden as it appears from the River", 1758.

Samuel Vaughan, Sketch plan of Mount Vernon, June–September 1787. “16. Kitchen Gardens.”

John Nancarrow, "Plan of the Seat of John Penn jun’r: Esqr: in Blockley Township and County of Philadelphia," c. 1785. The “kitchen garden” is designated at “e,” at some distance from the main house.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, General Plan of a Marine Asylum and Hospital proposed to be built at Washington, 1812. Kitchen gardens are indicated on the far left of the plan.

Anonymous, “Plan of the foregoing grounds as a Country Seat, after ten years' improvement,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), 114, fig. 24. The "kitchen garden adjacent at h”.

Anonymous, “Plan of a Mansion Residence, laid out in the natural style,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), 115, fig. 25. A kitchen garden is indicated at “d.”

Anonymous, “Plan of a Suburban Villa Residence,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), 118, fig. 26. The “kitchen garden” is designated at “c.”

Anonymous, “View of a Picturesque farm (ferme ornée),” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening 4th ed. (1849), 120, fig. 27. ". . . the kitchen garden at e."

Associated

J. C. Loudon, Kitchen garden, in An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1834), 721, fig. 696.

Anonymous, “Plan of a Suburban Garden,” in A. J. Downing, ed., Horticulturist 3, no. 8 (February 1849): pl. opp. 353.

Attributed

Jonathan Buddington, View of the Cannon House and Wharf, 1792.

Rebecca Chester, A Full View of Deadrick’s Hill, 1810.

Charles H. Wolf, attr., Pennsylvania Farmstead with Many Fences, c. 1847. A kitchen garden can be seen in the center of the image between the two buildings.

Notes

- ↑ Mary Ambler, “The Diary of M. Ambler,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 45 (April 1937): 166, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Benjamin Franklin to Mrs. Mary Hewson, May 6, 1786, quoted in Agnes Addison Gilchrist, “Market Houses in High Street,” Historic Philadelphia (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1953), 304–12, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Gardens producing vegetables and fruit for sale were often called “market gardens” and were an important source of income for many living in the vicinity of markets. For example, in 1791 a slave named Sophia Browing sold produce from her market garden at the Alexandria market, eventually earning the four hundred dollars to buy her husband’s freedom. See Mary Beth Corrigan, “The Ties That Bind: The Pursuit of Community and Freedom among Slaves and Free Blacks in the District of Columbia, 1800–1860,” in Southern City, National Ambition: The Growth of Early Washington, DC, 1800–1860, ed. Howard Gillette Jr. (Washington, DC: George Washington University, Center for Washington Area Studies, 1995), 75, view on Zotero. Also see Gregory J. Brown, “Distributing Meat and Fish in Eighteenth-Century Virginia,” Research Report on file, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Department of Archaeological Research (1988), 5. For an in-depth discussion about the development of markets in 19th-century America, see Helen Tangires, “Meeting on Common Ground: Public Markets and Civic Culture in Nineteenth-Century America” (PhD diss., George Washington University, 1999), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas S. Kirkbride, “Description of the Pleasure Grounds and Farm of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane with Remarks,” American Journal of Insanity 4, no. 4 (April 1848): 352, view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (New York: G. P. Putnam, 1850), 118, fig. 26, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jefferson to Mr. Bacon, February 1, 1808, in Thomas Jefferson, The Garden Book, ed. Edwin M. Betts (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1944), 360, view on Zotero. Also see Peter Martin, Pleasure Gardens of Virginia (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991), 148, view on Zotero. For a discussion of the broader aesthetic and political implications of the ferme orneé, also see Therese O’Malley, “Landscape Gardening in the Early National Period,” in Views and Visions, American Landscape Before 1830, ed. Edward J. Nygren with Bruce Robertson (Washington, DC: Corcoran Gallery of Art, 1986), 135–37, view on Zotero; William A. Brogden, “The Ferme Ornée and Changing Attitudes to Agricultural Improvement,” Eighteenth Century Life 8 (January 1983): 39–40, view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Byrd, The London Diary, 1717–1721, and Other Writings, ed. Louis B. Wright and Marion Tinling (New York: Oxford University Press, 1958), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Pehr Kalm, The America of 1750: Peter Kalm’s Travels in North America. The English Version of 1770, 2 vols. (New York: Wilson-Erickson, 1937), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Fred Shelley, ed., “The Journal of Ebenezer Hazard in Virginia, 1777”, Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 62 (1954): 400–23, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John D. Norton and Susanne A. Schrage-Norton, “The Upper Garden at Mount Vernon Estate—Its Past, Present, and Future: A Reflection on 18th Century Gardening. Phase II: The Complete Report” (Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association Library, 1985), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Bentley, The Diary of William Bentley, D.D., Pastor of the East Church, Salem, Massachusetts (Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1962), view on Zotero.

- ↑ François-Alexandre-Frédéric duc de La Rochefoucauld Liancourt, Travels through the United States of North America, the Country of the Iroquois, and Upper Canada, in the Years 1795, 1796, and 1797, ed. Brisson Dupont and Charles Ponges, trans. H. Newman, 2nd ed., 4 vols. (London: R. Philips, 1800), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Frederick Doveton Nichols and Ralph E. Griswold, Thomas Jefferson, Landscape Architect (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1978) , view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Drayton, “The Diary of Charles Drayton I, 1806,” Drayton Papers, MS 0152, Drayton Hall, SC, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alan Emmet, So Fine a Prospect: Historic New England Gardens (Hanover, NH University Press of New England, 1996), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Robert Waln Jr., “An Account of the Asylum for the Insane, Established by the Society of Friends, near Frankford, in the Vicinity of Philadelphia,” Philadelphia Journal of the Medical and Physical Sciences 1 (1825): 225–51, view on Zotero.

- ↑ James Boyd, A History of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1827–1927 (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1929), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Harriet Martineau, Retrospect of Western Travel, 2 vols. (London: Saunders and Otley, 1838), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America, 4th ed. (1849; Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Mason Hovey, “Notes of a Visit to Oatlands, Hempstead, L.I., N.Y., the Residence of D. F. Manice, Esq.,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 15, no. 12 (December 1849): 529–33, view on Zotero.

- ↑ R. B. Leuchars, “Notes on Gardens and Gardening in the neighborhood of Boston,” The Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 16, no. 2 (February 1850): 49–60, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Parkinson, Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris (London: Humfrey Lownes and Robert Young, 1629), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Wood, New England’s Prospect, ed. Alden T. Vaughan (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1977), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jean de La Quintinie, The Compleat Gard’ner, or Directions for Cultivating and Right Ordering of Fruit-Gardens and Kitchen Gardens, trans. John Evelyn (1693; repr., New York: Garland, 1982), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Ephraim Chambers, Cyclopaedia, or An Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences. . . , 5th ed., 2 vols. (London: D. Midwinter et al., 1741–43), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Philip Miller, The Gardeners Dictionary (1754; repr., New York: Verlag Von J. Cramer, 1969), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language: In Which the Words Are Deduced from the Originals and Illustrated in the Different Significations by Examples from the Best Writers, 2 vols. (London: W. Strahan for J. and P. Knapton, 1755), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Clarissa F. Dillom, ““A Large, an Useful, and a Grateful Field”: Eighteenth-Century Kitchen Gardens in Southeastern Pennsylvania, the Uses of the Plants, and Their Place in Women’s Work” (PhD diss., Bryn Mawr College, 1987), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Mawe and John Abercrombie, The Universal Gardener and Botanist, or A General Dictionary of Gardening and Botany (London: Printed for G. Robinson et al., 1778),view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel Deane, The New-England Farmer, or Georgical Dictionary (Worcester, MA: Isaiah Thomas, 1790), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Marshall, An Introduction to the Knowledge and Practice of Gardening, 1st American ed., 2 vols. (Boston: Samuel Etheridge, 1799), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Forsyth, A Treatise on the Culture and Management of Fruit Trees (Philadelphia: J. Morgan, 1802), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Humphry Repton, Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (London: Printed by T. Bensley for J. Taylor, 1803), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bernard M’Mahon, The American Gardener’s Calendar: Adapted to the Climates and Seasons of the United States. Containing a Complete Account of All the Work Necessary to Be Done. . . for Every Month of the Year. . . (Philadelphia: Printed by B. Graves for the author, 1806), view on Zotero.

- ↑ George Gregory, A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences, 1st American ed., 3 vols. (Philadelphia: Isaac Peirce, 1816), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, 4th ed. (London: Longman et al., 1826), view on Zotero.

- ↑ H. A. S. (Henry Alexander Scammell) Dearborn, An Address Delivered before the Massachusetts Horticultural Society (Boston: J. T. Buckingham, 1833), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, “Gardens,” New England Farmer, and Horticultural Journal 8, no. 12 (October 9, 1829): 92, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Bridgeman, The Young Gardener’s Assistant, 3rd ed. (New York: Geo. Robertson, 1832), view on Zotero.

- ↑ George William Johnson, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening, ed. David Landreth (Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1847), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. Downing, “Design for a Suburban Garden,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 3, no. 8 (February 1849): 380, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Geo. Kidd, “A Hint on Kitchen Gardens,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 3, no. 10 (April 1849): 471–72, view on Zotero.