Flower garden

See also: Bed, Border, Edging, Lawn, Parterre, Pleasure ground, Shrubbery, Walk

History

The meaning of the term flower garden remained relatively unchanged between 1650 and 1850, and the placement of the flower garden within a designed landscape, as well as the plants and their arrangement contained therein, helped distinguish it from other garden features. Although flowers might appear in kitchen gardens, the kitchen garden carried connotations of utility while the flower garden signified ornament and pleasure. Moreover, the flower garden required specialized care and expertise, as implied by Charles Carroll (of Annapolis) in his 1775 query about the training of a potential gardener.

The siting of the flower garden distinguished it from the kitchen garden and orchard, which, as mainly utilitarian features, were often situated beyond the view of the main house. Flower gardens, in keeping with their ornamental function, were often placed in relative proximity to the most prestigious rooms of the house. In this location they could be viewed from the house and could act as adjuncts to reception and entertaining rooms. Some 18th-century British treatise writers stated that the flower garden should be situated at the “back-front” of the house, meaning the area adjacent to the rear of the house and often just below the terrace. Such a location also provided a degree of shelter conducive to nurturing plants.

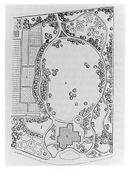

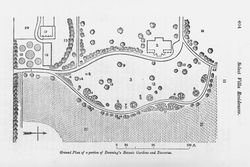

Flower gardens also could be placed at some distance from the house. Batty Langley (1728), for example, advised situating the flower garden within a wilderness. At the seat of John Penn, near Philadelphia, the flower garden was located in a wooded area away from the mansion [Fig. 1]. This placement of the flower garden distinguished it from the parterre, which, typically in the British and European context, was placed adjacent to the house. The 18th-century parterre used common plants, whereas the 18th-century flower garden was often devoted to exotic, unusual, or rare plants; hence Benjamin Henry Latrobe (1796) expressed disappointment in the flower garden at Mount Vernon because it contained “nothing very rare.” This “neat” layout arranged with precision met with Latrobe’s sarcasm as he described a parterre as “the expiring groans I hope of our Grandfather’s pedantry.” A sketch of John Bartram's famous garden depicts the botanist’s care and interest in “new flowers,” which were separated from the “common flower garden” [Fig. 2].

In England, long narrow beds were associated with florists’ gardens, which were devoted to the cultivation of rare or “choice” flowers, also known as “florists’ flowers.” Bernard M'Mahon's prescription in 1806 for a flower garden composed of narrow beds and planted with bulbous and tuberous rooted flowers, “each sort principally in separate beds,” suggests this English florist tradition.

By the 18th century in England, regular, geometric layout gave way to a new type of flower garden: island beds set into a lawn. Isaac Ware (1756) proposed planting flowers so as to resemble a nosegay emerging out of green lawn.[1] The island (or kidney-shaped bed), composed of flowers arranged in concentric circles or in a grid, gradually became a popular mode of flower garden design in 18th- and 19th-century English gardens.[2] Such practices were adopted in America in the 19th century.

J. C. Loudon An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826) attempted to order and clarify the increasing profusion of flower garden types by establishing a typology. For small gardens, he recommended a “regular figure” enclosed by a hedge. For larger gardens, Loudon recommended what he called an “irregular,” or alternately, a “modern” style garden, characterized by small groups or “garden scenes” of flowers set in the lawn and interspersed with shrubs. Loudon, in describing the modern garden, addressed an issue that had emerged for treatise writers of his time. As shrubbery developed as a garden feature, and as flowering shrubs were increasingly included in flower gardens, the “lines of distinction between the Flower Garden, the Shrubbery, and the Pleasure Ground,” as John Abercrombie and James Mean observed in The Practical Gardener (1817), “can neither be positively marked, nor constantly observed.” Indeed, writer Basil Hall (1828) conflated flowering shrubs in shrubbery and those in the flower garden when describing a plantation in the South.

Loudon outlined four types or classes of flower gardens. The first was the “general” or “mingled” flower garden, one in which graduated rows of flowers and shrubs were planted in a loose quincunx pattern that allowed taller species to rise up behind shorter species. In An Encyclopaedia, Loudon included a plan for planting a flower garden with respect to alternating the colors and sizes of plants, as well as the time of the plants’ flowering. The second type, the “select” flower garden, included only “particular kinds of plants,” that were cultivated or hybridized flowers grown by nurseries or florists, which were often massed in irregular drifts. The “changeable” flower garden, the third type, plunged plants (presumably greenhouse- or hothouse-raised) in their pots to correspond with seasonal changes. The final type, the “botanic” flower garden, had plants “arranged with reference to botanical study.” A. J. Downing similarly attempted to systematize the flower garden in A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849), in which he discussed the “irregular” flower garden, the “English” flower garden, and the “old French” flower garden.

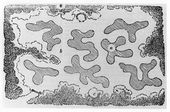

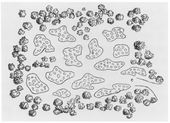

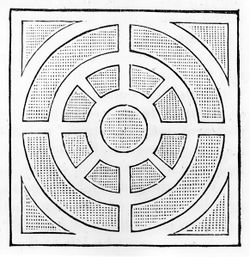

The 19th century witnessed another style of flower gardening: the “geometric” garden, as described in Downing’s 1847 article in the Horticulturist. The flower bed was divided into square or rectangular plots and subdivided into geometric figures. This manner of gardening had persisted since the 18th century and harkened back to such European Renaissance patterns as knots or cutwork parterres. The 1847 redesign of the Vassall-Craigie-Longfellow House flower garden in imitation of a Gothic stained-glass window was suggestive of this fashion [Fig. 3].

Greenhouses or conservatories were often located near or in flower gardens as they allowed for easy transport of plants. (See, for example, C. M. Hovey's 1839 description of Charles Phelps’s residence in Stonington, Connecticut.) At Montgomery Place, on the Hudson in New York, Downing (1847) placed the flower garden in front of the conservatory, echoing the “Moorish” character of this building with a flower garden designed to resemble an oriental carpet.

In addition to design and plant material, objects placed within the garden—seats, statues, arbors, and other decorative structures—contributed to the style of flower gardens. “Figures of statuary work of every character and description” characterized the “French” style according to Robert Buist (1841), whereas Jane Loudon (1845) included statues as well as vases, seats, basins of water, rustic baskets, and rock-work in the “modern English” flower garden. Edward Sayers, in The American Flower Garden Companion (1838), proposed a native American flower garden to be accompanied by a rustic seat and rockery in addition to a pond, shrubbery, and walk.

Given the plethora of styles and types of flower gardens in the nineteenth century, treatise writers emphasized the need for homeowners to select a mode of flower garden design that suited the characteristics of their house’s site and architecture, as well as the associative readings desired by the owners. Downing's explanation (1849) for why an “enthusiastic lover of the picturesque” whose residence was in the so-called “Rural Gothic” style would chose an “irregular” flower garden is an excellent example of this design logic.

Flower gardens often carried associations of status, wealth, and taste because of the expense of skilled gardening and of rare flower species.[3] Thomas Hancock in 1736, for example, fretted over the cost when he ordered plants, instructing that he wanted “Particular, Curious Things not of a high price.” Hancock’s concern about the potential financial liability of flowers was warranted. In 1737, for an order shipped from England of a “Baskett of flowers” (which, in fact, had arrived dead), he paid £26—a sizable amount of money considering that such luxury goods as lace, muslin, and silk could be purchased for a few pennies a yard.[4] While the cost of flowers declined with the growth of nurseries in America, prices remained relatively high compared to other goods and services.[5] For example, in 1839, the Ellwanger and Barry Nursery in Rochester, New York, sold a China Rose for $2.50 at a time when the average wage for nursery labor was $1.50 per day.[6] In 1850, Henry C. Bowen of Woodstock, Connecticut, a successful dry goods merchant, bought a tree peony for $1.00, the equivalent of the daily wage that he paid his laborers.[7] Thus the flower garden proposed by treatise writer Joseph Breck in 1851 at the cost of $10.00 dollars was the equivalent to approximately ten days’ salary for a laborer. Breck’s recommendation of old-fashioned plants as opposed to new hybrids or florists’ flowers may have been, in part, an attempt to decrease the cost of a flower garden.

The high cost of flowers enhanced the cachet of flower gardens. Despite her protests that she had neither taste nor the time, Caroline Bell (1831) expended much energy to create a garden that she hoped would be “pleasing to the eye or comfortable.” Treatise writers echoed and encouraged such attention. Charles Marshall (1799) wrote that no trouble should be spared in cultivating the “choicest gifts of Flora”; Thomas Green Fessenden (1828) claimed that “flower gardens were ever held in high estimation by persons of taste”; and C. M. Hovey (1844) insisted that “the flower garden is an appendage to almost every residence” and therefore should be planted in “a judicious manner” in order to be “an object of importance.” Fessenden also capitalized upon the notion of the flower garden as an index of taste when he proposed that young ladies cultivate flower gardens to learn neatness and correct taste and ideas. Writer M. A. W. (1840) commended flower gardening as a test of the gardener’s taste and skill. This didactic aspect of the flower garden resided in the link between gardening and moral behavior. Fessenden (1828) argued that by caring for plants young persons could learn that “every moral virtue must be protected, and every corrupt passion and propensity subdued.” Walter Elder (1849) implied that flower gardens could keep at bay the physical and moral corruption that he associated with the urban environment. Robert Squibb (1727; repr., 1827), in keeping with his notion that flowers were an expression of divinity, believed that flowers could ennoble, “refine,” and comfort their beholders and caretakers. Consistent with these discourses, many 19th-century institutions responsible for the care of individuals (including orphanages and insane asylums) kept flower gardens.

The labor and exercise associated with flower gardens resulted in their promotion as a source of healthy activity. Fessenden argued that flower gardens crossed class lines and appealed to everyone, and he described tending gardens as particularly suitable exercise for older citizens. Elder, in touting gardening for city dwellers, stipulated that no other activity could “more plainly bespeak” the “health and happiness” of the family. Sayers (1838) also argued that flower gardens were particularly healthful for city dwellers, basing his argument upon the notion that gardening helped to dispel the noxious vapors that condensed and settled on the ground.

Such texts helped to imbue flower gardens with pastoral, anti-urban associations and encouraged the recognition of the feature as a sign of the transformation of the American “wilderness” into a cultivated, even utopian, landscape. As was written in the Magazine of Horticulture in 1844, flower gardens suggested to the traveler “the steady march of taste and refinement, and the progress, though slow, of that art that transforms the wildest forest into a very Eden.”

—Anne L. Helmreich

Texts

Usage

- Lawson, John, 1709, describing North Carolina[8]

- “The Flower-Garden in Carolina is as yet arriv’d but to a very poor and jejune Perfection. We have only two sorts of Roses; the Clove-July-Flowers, Violets, Prince Feather, and Tres Colores.”

- Hancock, Thomas, December 20, 1736, requesting items for the garden of Thomas Hancock on Beacon Hill, Boston, MA (quoted in Hedrick 1988: 49)[9]

- “If you have any Particular, Curious Things not of a high price will Beautifie a flower Garden, Send a Sample with the price or a catalogue of ‘em. . . My Gardens all Lye on the South Side of a hill, with the most Beautifull Assent to the Top & it is Allowed on all hands the Kingdom of England don’t afford So Fine a Prospect as I have both of Land and water. Neither do I intend to Spare any Cost or Pains in making my Gardens Beautifull or Profitable.”

- Anonymous, 1 July 1771, describing in the New York Gazette or Weekly Post Bay a property in Staten Island, NY (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “To be SOLD. THE pleasant situated Place or Farm of LAWRENCE ROOME. . . on the North Side of Staten Island. . . There is on said Farm, a large Stone House and Kitchen. . . a neat Flower Garden before the door, also a large Kitchen Garden behind the House, all in Pale Fence.”

- Carroll, Charles (of Annapolis), 1775, describing Carroll Garden, Annapolis, MD (Maryland Historical Society, A. E. Carroll Papers)

- “Examine the Gardiner strictly as to. . . in what Branch He had been Chiefly employed, ye Kitchen or Flower Garden.”

- Bentley, William, June 12, 1791, describing Pleasant Hill, seat of Joseph Barrell, Charlestown, MA (1962: 1:264)[10]

- “[June] 12. Was politely received at dinner by Mr Barrell, & family, who shewed me his large & elegant arrangements for amusement, & philosophic experiments. . . His Garden is beyond any example I have seen. A young grove is growing in the back ground, in the middle of which is a pond, decorated with four ships at anchor, & a marble figure in the centre. The Chinese manner is mixed with the European in the Summer house which fronts the House, below the Flower Garden.”

- Latrobe, Benjamin Henry, July 19, 1796, describing Mount Vernon, plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (1977: 1:165)[11]

- “The ground on the West front of the house is laid out in a level lawn bounded on each side with a wide but extremely formal serpentine walk, shaded by weeping Willows. . . On one side of this lawn is a plain Kitchen garden, on the other a neat flower garden laid out in squares, and boxed with great precission. Along the North Wall of this Garden is a plain Greenhouse. The Plants were arranged in front, and contained nothing very rare, nor were they numerous. For the first time again since I left Germany, I saw here a parterre, chipped and trimmed with infinite care into the form of a richly flourished Fleur de Lis: The expiring groans I hope of our Grandfather’s pedantry.”

- Clitherall, Eliza Caroline Burgwin, active 1801, describing the Hermitage, seat of John Burgwin, Wilmington, NC (quoted in Flowers 1983: 126)[12]

- “These [gardens] were extensive and beautifully laid out. There was [sic] alcoves and summer houses at the termination of each walk, seats under trees in the more shady recesses of the Big Garden, as it was called, in distinction from the flower garden in front of the house.”

- Hamilton, Alexander, c. 1802, describing Hamilton Grange, estate of Alexander Hamilton, New York, NY (quoted in Hamilton 1910: 348)[13]

- “3. If it can be done in time I should be glad if space could be prepared in the center of the flower garden for planting a few tulips, lilies, hyacinths, and [missing]. The space should be a circle of which the diameter is Eighteen feet: and there should be nine of each sort of flowers; but the gardener will do well to consult as to the season.

- “They may be arranged thus: Wild roses around the outside of the flower garden with laurel at foot.”

- Martin, William Dickinson, 1809, describing the pleasure grounds at Salem Academy, Salem, NC (quoted in Bynum 1979: 29)[14]

- “Next, I visited a flower garden belonging to the female department. The flowers were very numerous, but none of them remarkable for their beauty or novelty—the garden was badly laid off, for it possessed neither taste, elegance nor convenience: the soil appeared barren & unproductive, & the flowers by no means flourishing. There was nothing uncommon in the garden.”

- Hall, Capt. Basil, 1828, describing a plantation he visited during his trip from Charleston, SC to Savannah, GA (quoted in Jones 1957: 98)[15]

- “From the drawing-room, we could walk into a verandah or piazza, from which, by a flight of steps, we found our way into a flower garden and shrubbery, rich with orange trees, laurels, myrtles, and weeping willows, and here and there a great spreading aloe.”

- Bell, Caroline, July 10, 1831, in a letter to Frances P. Butler, describing Plaqumine, Iberville, LA (Historic New Orleans Collection, Butler Family Papers, folder 545, MS 102)

- “You tell me to procure all the flowers & shrubs possible—this I will certainly do—& am sure you will do the same—and under your direction—I have not the least doubt, our Gardens will be most beautiful, and flourish—for my part my dear I have neither taste (altho’ I admire flower Gardens as much as any one) or time to devote to those things at least not as much as is necessary—I hope you will be more fortunate than I have been, I have made every exertion to have a great many Monthly Roses, without success, as I do not think that a dozen have taken—owing intirely, I believe, to the Yards being in White Clover—I have been equally unfortunate with the most beautiful, of all flowering shrubs—The flowering Pomgrancete [sic]—I’m sure I have set out the Pomigranite, the Rose and many other things half a dozen times— When they have died—Mr Bell thinks we will be obliged to cultivate the Yard to have things do well in it—I am of the same opinion—however we are in hopes that the Bermuda Grass sods which we have set about thro’ the yard—in time—will get the better of the Clover. Much, very much, is yet to do here, to render our place either pleasing to the eye or comfortable.”

- Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), March 1835, “Notices of Some of the Gardens and Nurseries in the Neighborhood of New York and Philadelphia; taken from Memoranda made in the Month of March last” (American Gardener’s Magazine 1: 241)[16]

- “There is another class of gardens in Philadelphia, called public gardens, which combine in addition to a flower garden, green-houses, hothouses, &c., a bar-room or tavern; this latter addition we are far from believing useful or needful.”

- Breck, Joseph, July 1, 1837, “Calls at Gardens and Nurseries in the Vicinity of Boston” (Horticultural Register 3: 271–72)[17]

- “One of the most interesting spots is the boys’ flower garden, an oblong square piece, handsomely fenced off, containing perhaps about a quarter of an acre. Every boy has his own spot, which is laid and planted to suit his own fancy, and the whole forms an assemblage of squares, triangles, circles, segments of circles, and every possible shape that their boyish notions dictated.”

- Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), October 1839, “Some Remarks upon Several Gardens and Nurseries in Providence, Burlington, (N.J.) and Baltimore,” describing the residences of Charles Phelps, Esq., Stonington, CT, and Horace Binney, Burlington, NJ (Magazine of Horticulture 5: 363)[18]

- “The flower garden contains about a quarter of an acre, in front of the house, and between that and the road, and is walled in on the north and west side. It is tastefully laid out in small beds, edged with box; on the north side stands a moderately sized green-house, about forty feet long.”

- “The flower garden is nearly a square, and is laid out with one main circular walk, running round the whole, and a border for flowers on each side; the centre forming a lawn scattered over with several large fruit trees.”

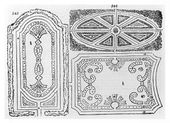

- Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), November 1841, “Select Villa Residences,” describing Highland Place, estate of A. J. Downing, Newburgh, NY (Magazine of Horticulture 7: 406–9)[19]

- “18. Flower garden, in front of the greenhouse. It is laid out in circular beds, edged with box, with gravel walks. Under the arbor vitae hedge, which is here planted against the boundary line, the green-house plants are principally placed during summer. . .

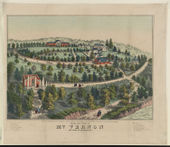

- “the flower garden (18,) a small space laid out with seven circular beds; the centre one nearly twice as large as the outer ones: these were all filled with plants: a running rose in the centre of the large bed, and the outer edge planted with fine phloxes, Bourbon roses, &c.: the other six beds were all filled with similar plants, excepting the running rose, which would be of too vigorous growth for their smaller size. Under the arbor vitae hedge here, on the south side of the garden, the green-house plants were arranged in rows, the tallest at the back.” [Fig. 4]

- B., P., January 1844, “Progress of Horticulture in Rochester, N.Y.” (Magazine of Horticulture 10: 17)[20]

- “Flower gardens and shrubberies are no longer objects of amazement; avenues of forest trees are not uncommon sights in the vicinity of dwellings; in fact the general neatness that pervades this beautiful section of country cannot fail to suggest to the traveller the steady march of taste and refinement, and the progress, though slow, of that art that transforms the wildest forest into a very Eden.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, October 1847, describing Montgomery Place, country home of Mrs. Edward (Louise) Livingston, Dutchess County, NY (quoted in Haley 1988: 52)[21]

- “Passing under neat and tasteful archways of wirework, covered with rare climbers, we enter what is properly

- “THE FLOWER GARDEN.

- “How different a scene from the deep sequestered shadows of the Wilderness! Here all is gay and smiling. Bright parterres of brilliant flowers bask in the full daylight, and rich masses of colour seem to revel in the sunshine. The walks are fancifully laid out, so as to form a tasteful whole; the beds are surrounded by low edgings of turf or box, and the whole looks like some rich oriental pattern of carpet or embroidery. In the centre of the garden stands a large vase of the Warwick pattern; others occupy the centres of parterres in the midst of its two main divisions, and at either end is a fanciful light summer-house, or pavilion, of Moresque character. The whole garden is surrounded and shut out from the lawn, by a belt of shrubbery, and above and behind this, rises, like a noble framework, the background of trees of the lawn and the Wilderness. If there is any prettier flower-garden scene than this ensemble in the country, we have not yet had the good fortune to behold it.” [Fig. 5]

- Longfellow, Samuel, November 16, 1847, in a letter to Alexander W. Longfellow, describing the Vassall-Craigie-Longfellow House, Cambridge, MA (quoted in Evans 1993: 42)[22]

- “At the Vassall-Craigie-Longfellow House|Craigie House there is nothing new I think save a new flower garden of larger growth which is in the process of completion under the direction of Richard Dolben Landscape gardener & florist from England & which promises to be very charming by next Summer, with a great Gothic Cathedral wheel or Rose-window in the centre.”

- Kirkbride, Thomas S., April 1848, describing pleasure grounds and farm of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, Philadelphia, PA (American Journal of Insanity 4: 349, 352)[23]

- “Between the north lodge and the deer-park, separated from the latter by a sunk palisade fence, is a neat flower garden. . . As on the men’s side, there is a private yard for females, and the flower-garden in front of the lodge, and the paved yards connected with it are similarly arranged. . . The cultivation of the gardens and the improvement of the pleasure grounds, offer the generality of patients the most desirable forms of labour. It is sufficiently varied, not too laborious, and in some division of it many will engage who could not be induced to assist upon the farm or in any other kind of employment, out of doors. . . The flower gardens should be as extensive as can be well taken care of by the inmates and persons employed in the Hospital. The good influences which these, as well as a high state of improvement about the buildings, generally produce on patients and their friends, is often of great importance.”

- Justicia [pseud.], March 1849, “A Visit to Springbrook,” seat of Caleb Cope, near Philadelphia, PA (Horticulturist 3: 411)[24]

- “We now sally forth into the flower garden. The flowers are grown in beds and masses, and consist of sorts that are either continually in bloom, or such as are succeeded by others from a reserve-garden, producing a magnificent display the entire season.”

- Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), December 1849, describing Oatlands, residence of D. P. Manice, Hempstead, NY (Magazine of Horticulture 15: 529–31)[25]

- “The house is a handsome building, in a kind of castellated gothic, standing about fifty feet from the road, with the conservatory and hothouse, and flower garden on the left,—the kitchen garden and forcing-houses on the right,—and the lawn and pleasure ground, in the rear of the house, separating it from the park. . .

- “Continuing our walk about the grounds, we entered the flower garden, which is laid out in beds, bordered with box; the dahlias were about all that remained in bloom at this late season, save here and there a stray rose.”

Citations

- La Quintinie, Jean de, 1693, The Compleat Gard’ner (1693; repr., 1982: n.p.)[26]

- “Thus was the Culture of Flowers begun indeed by such Gard’ners. . . when Men had a mind to have so great a number of them, as is now practised by way of Ornament, to the palaces of Great Persons, they begun to make particular Gardens of them which they called by a name proper to a Flower Garden; and because it was not possible for one Gard’ner at the same time, to manage the Culture of so great a number of Fruits, Legumes, Flowers, Shrubs, &c. as were then required, there was a necessity of establishing a second Class of Gard’ners, to ease those of the first, which new Gard’ners were commonly named Florists, to distinguish them from the others, which were called only plain Gard’ners. . .

- “Embroidery, is a term used in Flower Gardens, signifying, Flower Plots that are wrought in fine shapes, like patterns of Embroidery. . .

- “Gardens are choice inclosed pieces of Ground planted with Edible Plants, Fruit-Trees, and Flowers, and differ from Orchards, which are commonly planted with Standard Fruit-Trees, and are seldom walled, or so curiously inclosed as Gardens.

- “Kitchen-Gardens are chiefly for Kitchen and Edible Plants.

- “Fruit Gardens for Fruits.

- “And Flower-Gardens or Parterres, for Flowers. . .

- “Whence it is easie to conclude, how much I dislike in the Case of Kitchen-Gardens, all other Indented Figures, Diagonals, Rounds, Ovals, Triangles, &c. which are only proper for Thickets and Parterres, or Flower Gardens, in which Places they are at once both very useful, and of a great Beauty.”

- Langley, Batty, 1728, New Principles of Gardening (1728; repr., 1982: 195, 198)[27]

- “General DIRECTIONS, &c. . .

- “XIX. That in those serpentine Meanders, be placed at proper Distances, large Openings, which you surprizingly come to; and in the first are entertain’d with a pretty Fruit-Garden. . . from which you are insensibly led through the pleasant Meanders of a shady delightful Plantation; first, into an oven [sic] Plain. . . secondly, into a Flower-Garden, enrich’d with the most fragrant Flowers and beautiful Statues.”

- Deane, Samuel, 1790, The New-England Farmer (1790: 110)[28]

- “GARDEN, ‘a piece of ground cultivated and properly ornamented with a variety of plants, flowers, fruit-trees, &c. Gardens are usually distinguished into flower-garden, fruit-garden, and kitchen-garden: The first of which, being designed for ornament, is to be placed in the most conspicuous part, that is, next to the back front of the house; and the second and third, being designed for use, should be placed less in sight.’ Dict. of Arts.”

- Marshall, Charles, 1799, An Introduction to the Knowledge and Practice of Gardening (1799: 1:42)[29]

- “Mixed Gardening, as comprehending the useful with the sweet—the profitable with the pleasant, has been the subject hitherto, but if the flower garden and the kitchen garden are to be distinct things, the case is altered; yet not so much, but that still the kitchen garden should be adorned with a sprinkling of the more ordinary decorations, to skirt the quarters, which should be chiefly those of the most powerful sweet scents, as roses, sweet-briars, and honey-suckles, wall flowers, pinks, minionette, &c. in order to counteract the coarser effluvia of vegetables, or (perchance) of dead leaves.

- “The flower garden (properly so called) should be rather small than large; and if a portion of ground be separately appropriated for this, only the choicest gifts of Flora should be introduced, and no trouble spared to cultivate them in the best manner. The beds of this garden should be narrow, and consequently the walks numerous; and not more than one half or two thirds the width of the beds, except one principal walk all round, which may be a little wider. The gravel (or whatever the walks are made of) should lie about four inches below the edge. The beds for tulips, hyacinths, anemonies, ranunculuses, &c. may be three and an half, or four feet wide, and those for single flowers the same, or only two and a half feet wide in the borders; which was the most usual breadth in the old flower gardens, of which we have hardly an instance now. Let the mould lie rather rounded in the middle.”

- Repton, Humphry, 1803, Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1803: 99–101)[30]

- “If solitude delight, we seek it rather in the covert of a wood, or the sequestered alcove of a flower garden, than in the open lawn of an extensive pleasure ground. . .

- “Flower gardens on a small scale may, with propriety, be formal and artificial; but in all cases they require neatness and attention. . .

- “A flower garden should be an object detached and distinct from the general scenery of the place; and whether large or small, whether varied or formal, it ought to be protected from hares and smaller animals by an inner fence: within this enclosure rare plants of every description should be encouraged, and a provision made of soil, and aspect for every different class.”

- M’Mahon, Bernard, 1806, The American Gardener’s Calendar (1806: 55, 58, 71)[31]

- “THE district commonly called the Pleasure, or Flower-Garden, or Pleasure-ground, may be said to comprehend all ornamental compartments, or divisions of ground, surrounding the mansion; consisting of lawns, plantations of trees and shrubs, flower compartments, walks, pieces of water, &c. whether situated wholly within the space generally considered as the Pleasure-Garden, or extended to the adjacent fields, parks, or other out-grounds. . .

- “In the general arrangement, the great art is to vary the prospect of the different divisions, so as they may variously present an air of novelty, and source of convenience and entertainment. . .

- “Another part shall appear more gay and sprightly, displaying an elegant flower-ground, or flower-garden, designed somewhat in the parterre way, in various beds, borders, and other divisions, furnished with the most curious flowers; and the boundary decorated with an arrangement of various clumps, of the most beautiful flowering shrubs, and lively ever-greens, each clump also bordered with a variety of the herbaceous flowery tribe. . .

- “A commodious piece of good ground, for a flower-garden, situated in a convenient and well sheltered place, and well exposed to the sun and air, ought to be allotted for the culture of the more curious and valuable flowers.

- “The form of this ground may be either square, oblong, or somewhat circular; having the boundary embellished with a collection of the most curious flowering-shrubs; the interior part should be divided into many narrow beds, either oblong, or in the manner of a parterre; but plain four feet wide beds arranged parallel, having two feet wide alleys between bed and bed, will be found most convenient, yet to some not the most fanciful.

- “In either method, a walk should be carried round the outward boundary, leaving a border to surround the whole ground, and within this, to have the various divisions or beds, raising them generally in a gently rounding manner, edging such as you like with dwarf-box, some with thrift, pinks, sisyrinchium, &c. by way of variety, laying the walks and alleys with the finest gravel. Some beds may be neatly edged with boards, especially such as are intended for the finer sorts of bulbs, &c.

- “In this division you may plant the finest hyacinths, tulips, polyanthus-narcissus, double jonquils, anemones, ranunculus’s, bulbous-iris’s, tuberoses, scarlet and yellow amaryllis’s, colchicums, fritillaries, crown-imperials, snowdrops, crocus’s, lilies of various sorts, and all the different kinds of bulbous, and tuberous-rooted flowers, which succeed in the open ground; each sort principally in separate beds, especially the more choice kinds, being necessary both for distinction sake and for the convenience of giving, such as need it, protection from inclement weather; but for particulars of their culture, see the respective articles in the various months.”

- Abercrombie, John, with James Mean, 1817, Abercrombie’s Practical Gardener (1817: 337–40, 347, 433, 460)[32]

- “But in the Pleasure Ground, the gardener’s professed object is elegance; and the stores of vegetation, from the stage of flowers in the fore-ground to the hanging grove in the distance, are scattered about to augment the beauty of the landscape.

- “The lines of distinction between the Flower Garden, the Shrubbery, and the Pleasure Ground, can neither be positively marked, nor constantly observed. . . The flowering shrubs connect the two former. . .

- “The most essential point of separation between a Flower Garden and a Pleasure Ground seems to turn on the extent of the place. . .

- “With regard to the form, either a square or an oblong ground-plan is eligible; and although the shape must be often adapted to local circumstances, yet when a garden is so circumscribed that the eye at once embraces the whole, it is desirable that it should be of some regular figure.

- “Fences.—The Flower Garden, which is not an appendage to ornamented grounds, will require a fence, whenever the domestic buildings do not serve as a boundary. For the inclosure, a wall or close paling is on two accounts to be preferred on the north side; both to serve as a screen, and to afford a warm internal face for training fruit-trees. When one of those is not adopted, recourse may be had to a good hedge-fence, planted on a bank, and defended by an outward ditch. . .

- “For internal fences, to afford shade or shelter to particular compartments, yew, holly, laurel, and some of the other evergreens are occasionally used. . .

- “Style of laying out a Flower Department.—If a piece of ground be set apart for the cultivation of flowers, in what style should it be laid out? This may vary with the quantity of surface and the object of the cultivator. In the first place, carry a border round the garden, nowhere narrower than three or four feet. . . . In contact with the surrounding border, may be either a grass-plat or a gravel-walk. . . If the ground be at all dilated, handsome walks, crossing or leading to the centre, will be also requisite: let the principal walks be five or six feet in breadth. The interior of the garden is usually laid out in oblong beds three or four feet wide, with intervening alleys two feet wide, or from that down to twelve inches, when it is intended to abstract as little space as possible from the cultivation of the flowers; or, the same end may be attained by circular or oval beds, with smaller compartments between, of such a form as will leave the alleys of one regular width. The alleys, as well as the main walks, should be laid with gravel or some dry binding material; and the beds edged with box or thrift: box is to be preferred. Keep the edgings neat and regular, about two inches in height and breadth, by clipping them once or twice a year, in the interval from April to September. See also SHRUBBERY, Planting Box-Edgings; and Edgings of Borders and Gravel-walks, under the head PLEASURE GROUND.

- “Ground worked on the above plan may have regular divisions without being formal. The apology for beds and walks, varying in shape and direction, but finished in minute detail, must be, that the process of nature herself, in the small efflorescent plants, is delicate; the consummation of the process exquisite; and that the beauties of a flower can only be discerned on a near view. The more concentrated the beds in relation to the house, and the easier the approach, the greater will be the entertainment derived from those plants which, in the mode of germination, or foliation, or coming into flower, or showing and maturing fruit or seed-vessels, offer subjects for curious observation.

- “Quadrangular and circular patches on the side next the house may be laid with turf, which will have a good effect from the windows; besides, if the domestics have a passage through that quarter, flower-beds would be constantly exposed to casual injury. . .

- “For the regular beds of a professed Flower Department, choice and curious species should be chiefly selected,—comprehending prime varieties of the Tulip, Hyacinth, and Jonquil, the Polyanthus-narcissus, and other esteemed kinds of the Narcissus, the Fritillaria, Crown-imperial, Bulbous Iris, Persian Iris, Amaryllis, Ranunculus, Anemone, with such other BULBOUS and TUBEROUS-ROOTED FLOWERS as are chiefly prized; likewise of the FIBROUS-ROOTED TRIBE, admit the capital sorts of the Auricula, Polyanthus, Carnation, and Pink, with the beautiful or extraordinary among the other kinds enumerated in the respective tables of that class, Annuals, Biennials, and Perennials. . .

- “Distribution in the Garden.—As to the distribution of these hardy sorts in the garden: it is principally in small patches in the borders or beds, or separately in pots; to remain where sown for flowering. Observe, in placing the seeds in the compartments, to dispose the lower-stemmed plants towards the front. . . The larger in the next degree may stand proportionally more inward or retiring. . . The blossoms borne on the tallest stems will sufficiently strike the eye, in stations still farther removed from the front, near the back-part of borders or the centre of circular beds. . . Be careful so to distribute the patches, that each sort in full growth may stand separate, and distinct to view. Confine the seeds to the principal sorts, and sow a smaller number, rather than crowd the borders confusedly. . .

- “THE distinction between a Flower Garden and a Shrubbery, as an ornamental portion of ground, has been loosely marked in the opening of the last division. One branch of the ancient system of gardening was, to make large plantations entirely of shrubs intersected by gravel-walks: but this is now almost universally exploded; and shrubs are usually distributed over the grounds, sometimes in association with flowers, and sometimes with trees, or for a short space in a continued line, as the object is ornament, or shelter, or to form a side-screen. . .

- “The sense, however, in which we employ Shrubbery, as the title of this article, is merely that of a treatise on the culture of shrubs. . .

- “While the Kitchen Garden is concealed by buildings or plantations, the Flower Garden and Pleasure Ground should stand conspicuously attached to the family-residence.”

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826: 789–95, 797–98, 800, 1020)[33]

- “6075. Floriculture. . . The culture of flowers was long carried on with that of culinary vegetables, in the borders of the kitchen-garden, or in parterres or groups of beds, which commonly connected the culinary compartments with the house. In places of moderate extent, this mixed style is still continued; but in residences which aim at any degree of distinction, the space within the walled garden is confined to the production of objects of domestic utility, while the culture of plants of ornament is displayed in the flower-garden and the shrubbery. These, under the general term of pleasure-ground, encircle the house in small seats, and on a larger scale embrace it in one or more sides; the remaining part being under the character of park-scenery. . .

- “6076. The situation of the flower-garden, as of every department of floriculture, should be near the house, for ready access at all times, and especially during winter and spring, when the beauties of this scene are felt with peculiar force. . .

- “6079. To place the flower-garden south-east or south-west of the house, and between it and the kitchen-garden, is in general a desirable circumstance. . .

- “6080. In exposure and aspect, the flower-garden should be laid out as much as possible on the same principles as the kitchen-garden. . .

- “6081. The extent of the flower-garden depends jointly on the general scale of the residence, and the particular taste of the owner. If any proportion may be mentioned, perhaps, a fifth part of the contents of the kitchen-garden will come near the general average; but there is no impropriety in having a large flower-garden to a small kitchen-garden. . . As moderation, however, is generally found best in the end, we concur with the author of the Florist’s Manual, when she states, that ‘. . . If the form of ground, where a parterre is to be situated, is sloping, the size should be larger than when a flat surface, and the borders of various shapes, and on a bolder scale, and intermingled with grass; but such a flower-garden partakes more of the nature of pleasure-ground than of the common parterre, and will admit of a judicious introduction of flowering shrubs.’ . . .

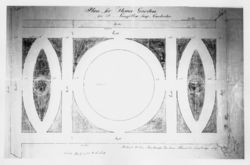

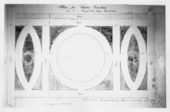

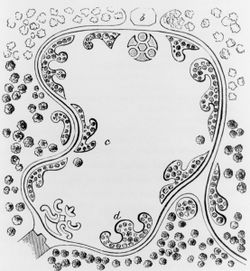

- “6082. Shelter is equally requisite for the flower as for the kitchen garden, and, where naturally wanting, is to be produced by the same means, viz. planting. . . Sometimes an evergreen hedge will produce all the shelter requisite, as in small gardens composed of earth and gravel only. . . but where the scene is large. . . and composed of dug compartments (a), placed on lawn (b) the whole may be surrounded by an irregular border (c) of flowers, shrubbery, and trees. . . [Fig. 6]

- “6086. Water. This material, in some form or other, is as essential to the flower as to the kitchen-garden. Besides the use of the element in common culture, a pond or basin affords an opportunity of growing some of the more showy aquatics, while jets, dropping-fountains, and other forms of displaying water, serve to decorate and give interest to the scene. . .

- “6087. The form of a small garden. . . will be found most pleasing when some regular figure is adopted, as a circle, oval, octagon, crescent, &c.: but where the extent is so great as not readily to be caught by a single glance of the eye, an irregular shape is generally more convenient, and it may be thrown into agreeable figures, or component scenes, by the introduction of shrubs so as to subdivide the space. . .

- “6090. Boundary fence, or screen. Parterres on a small scale may be enclosed by an evergreen hedge of holly, box, laurel, privet, juniper, laurustinus, or Irish whin. . . but irregular figures, especially if of some extent, can only be surrounded by a shrubbery, such as we have already hinted at (6082.) as forming a proper shelter for flower-gardens. . .

- “6093. Laying out the area. . . In laying out the area of the kitchen-garden, its destination being utility, affords in all cases a safe and fixed guide; but the flower-garden is a matter of fancy and taste, and where these are wavering and unsettled, the work will be found to go on at random. As flower-gardens are objects of pleasure, that principle which must serve as a guide in laying them out, must be taste. Now, in flower-gardens, as in other objects, there are different kinds of tastes; these embodied are called styles or characters; and the great art of the designer is, having fixed on a style, to follow it out unmixed with other styles, or with any deviation which would interfere with the kind of taste or impression which that style is calculated to produce. Style, therefore, is the leading principle in laying out flower-gardens, as utility is in laying out the culinary-garden. As subjects of fancy and taste, the styles of flower-gardens are various. The modern style is a collection of irregular groups and masses, placed about the house as a medium, uniting it with the open lawn. The ancient geometric style, in place of irregular groups, employed symmetrical forms; in France, adding statues and fountains; in Holland, cut trees and grassy slopes; and in Italy, stone walls, walled terraces, and flights of steps. In some situations, these characteristics of parterres may with propriety be added to, or used instead of the modern sort, especially in flat situations, such as are enclosed by high walls in towns, or where the principal building or object is in a style of architecture which will not render these appendages incongruous. There are other characters of gardens, such as Chinese, which are not widely different from the modern; the Indian, which consists chiefly of walks under shade, in squares of grass, &c.; the Turkish, which abounds in shady retreats, boudoirs of roses and aromatic herbs; and the Spanish, which is distinguished by trellis-work and fountains: but these gardens are not generally adapted to this climate, though from contemplating and selecting what is beautiful or suitable in each, a style of decoration for the immediate vicinity of mansions might be composed, greatly preferable to any thing now in use. . .

- “6099. The green-house or conservatory is generally placed in the flower garden, provided these structures are not appended to the house. . .

- “6110. The manner of planting the herbaceous plants and shrubs in a flower-garden depends jointly on the style and extent of the scene. With a view to planting, they may be divided into three classes, which classes are independently altogether of the style in which they are laid out. The first class is the general or mingled flower-garden, in which is displayed a mixture of flowers with or without flowering-shrubs according to its size. The object in this class is to mix the plants, as that every part of the garden may present a gay assemblage of flowers of different colors during the whole season. The second class is the select flower-garden, in which the object is limited to the cultivation of particular kinds of plants; as, florists’ flowers, American plants, annuals, bulbs, &c. Sometimes two or more classes are included in one garden, as bulbs and annuals; but, in general, the best effect is produced by limiting the object to one class only. The third class is the changeable flower garden, in which all the plants are kept in pots, and reared in a flower-nursery or reserve-ground. As soon as they begin to flower, they are plunged in the borders of the flower-garden, and, whenever they show symptoms of decay, removed, to be replaced by others from the same source. This is obviously the most complete mode of any for a display of flowers, as the beauties of both the general and particular gardens may be combined without presenting blanks, or losing the fine effect of assemblages of varieties of the same species; as of hyacinth, pink, dahlia, chrysanthemum, &c. The fourth class is the botanic flower-garden, in which the plants are arranged with reference to botanical study, or at least not in any way that has for its main object a rich display of blossoms. . .

- “6126. The botanic flower-garden being intended to display something of the vegetable kingdom, as well as its resemblances and differences, should obviously be arranged according to some system or method of study. . . [For a private botanic garden] a gravel walk may be so contrived as to form a tour of all the groups [of species]. . . displaying them on both sides; in the centre, or in any fitting part of the scene, the botanic hot-houses may be placed; and the whole might be surrounded with a sloping phalanx of evergreen plants, shrubs, and trees. . . It is hardly necessary to observe that the above modes, or others that we have mentioned of planting a flower-garden are alike applicable to every form or style of laying out the garden or parterre. . . [Fig. 7]

- “7259. The flower-garden should join both the conservatory and terrace; and, where the botanic stoves do not join the conservatory and the house, they, and also the aviary and other appropriate buildings and decorations, should be placed here.”

- Squibb, Robert, 1827, The Gardener’s Calendar for the States of North-Carolina, South-Carolina, and Georgia (1827: 1, 3)[34]

- “The Flower Garden.

- “It is a source of recreation and delight which but few are acquainted with, though calculated to exalt the mind, refine the taste and manners, and even qualify the temper, and sooth the feelings in many a gloomy hour. Flowers speak a language from the Creator. . .

- “The aspect of the [flower] garden is the next thing to be considered, which experience has proved to be best fronting the East or South-East, protected on the North and North-West by buildings or trees. The early suns; the cold winds which blow from the South-East, with the moisture accompanying those winds, are particularly favourable to our gardens; though many northern and eastern plants, and even from our interior, are obliged to be excluded from the gardens near Charleston on account of its vicinity to salt air.”

- Fessenden, Thomas Green, 1828, The New American Gardener (1828: 6, 109–10)[35]

- “Gardens are usually classed under the following heads:—the kitchen garden; the fruit garden; and the 'flower garden'. The flower garden, being designed principally for ornament, should be placed in the most conspicuous part, that is, in front, or next to the back part of the house; the kitchen garden and fruit garden may follow in succession. . .

- “FLOWERS, ORNAMENTAL.—Should the agriculturist have no taste for ornamental gardening, yet such is the laudable taste of the fair daughters of America, at the present day, that there are but comparatively few, that do not take an interest in a flower garden. . .

- “Flower gardens were ever held in high estimation by persons of taste. . .

- “The cultivation of flowers is an employment adapted to every grade, the high and the low, the rich and the poor; but especially to those who have retired from the busy scenes of active life. . . And what exercise is more fit for him, who is in the decline of life, than that of superintending a well ordered garden? . . .

- “Floriculture is peculiarly calculated for the amusement of youth. It may teach them many important lessons. . . Let them be instructed, that nothing valuable is to be obtained or preserved without labour, care, and attention—that as every valuable plant must be defended, and every noxious weed removed, so every moral virtue must be protected, and every corrupt passion and propensity subdued.

- “The cultivation of flowers is an appropriate amusement for young ladies. It teaches neatness, cultivates a correct taste, and furnishes the mind with many pleasing ideas. The delicate form and features, the mildness and sympathy of disposition, render them fit subjects to raise those transcendent beauties of nature, which declare the ‘perfections of the Creator’s power.’”

- Bridgeman, Thomas, 1832, The Young Gardener’s Assistant (1832: 110–12, 121)[36]

- “A Flower Garden should be protected from cold cutting winds by close fences, or plantations of shrubs, forming a close and compact hedge, which should be neatly trimmed every year. Generally speaking, a Flower Garden should not be upon a large scale; the beds or borders should in no part of them be broader than the cultivater can reach to, without treading on them: the shape and number of the beds must be determined by the size of the ground, and the taste of the person laying out the garden. Much of the beauty of a pleasure garden depends on the manner in which it is laid out; a great variety of figures may be indulged in for the Flower bed. Some choose oval or circular forms, others squares, triangles, hearts, diamonds, &c., and intersected winding gravel walks.

- “Neatness should be the prevailing characteristic of a Flower Garden, and it should be so situated as to form an ornamental appendage to the house; and where circumstances will admit, placed before windows exposed to a southern or southeastern aspect. The principle on which it is laid out, ought to be that of exhibiting a variety of colour and form, so blended as to present one beautiful whole. In a small Flower Garden, viewed from the windows of a house, this effect is best produced by beds, or borders formed on the side of each other, and parallel to the windows from whence they are seen, as by that position the colours show themselves to the best advantage. In a retired part of the garden, a rustic seat may be formed, over and around which honey-suckles and other sweet and ornamental creepers and climbers may he [sic] trained on trellises, so as to afford a pleasant retirement.

- “Although the greatest display is produced by a general flower garden, that is, by cultivating such a variety of sorts in one bed or border as may nearly insure a constant blooming, yet bulbous plants, while essential to the perfection of the Flower Garden, lose something of their peculiar beauty when not cultivated by themselves. The extensive variety of bulbous roots furnish means for the formation of a garden, the beauty of which arising from an intermixture of every variety of form and colour, would well repay the trouble of cultivation, particularly as by a judicious selection and management, a succession of bloom may be kept up for some length of time. As, however, bulbous flowers lose their richest tints about the time that annuals begin to display their beauty, there can be no well founded objection to the latter being transplanted into the bulbous beds, so that the opening blossoms of the annuals may fill the place of those just withered, and continueto [sic] supply the flower beds with all the gaiety and splendour of the floral kingdom.

- “But the taste of the florist will be exercised to little purpose, in his selection of flowers, if he does not pay strict attention to the general state of his garden. If there are lawns or grass walks, they should be frequently trimmed, and more frequently mowed and rolled, to prevent the grass from interfering with the flower beds, and to give the whole a neat regular carpet-like appearance. If there are gravel walks, they should be frequently cleaned, replenished with fresh gravel, and rolled. Box and other edgings should be kept clear of weeds, and neatly trimmed every spring. Decayed plants should be removed, and replaced with vigorous ones from the nursery bed. Tall flowering plants must be supported by neat poles or rods; and all dead stalks and leaves from decayed flowers, most be frequently removed. . .

- “The plants should be so arranged that they may all be seen. The most dwarfish may be placed in front, and others in a regular gradation to the tallest behind; or the tallest may be planted along the middle of the beds, and the others on each side according to their varied heights and colours.”

- Anonymous, December 5, 1832, “On Planting a Flower Garden” (New England Farmer 11: 164)[37]

- “The most efficacious plan for accomplishing this, and making the thing intelligible to every one, would be by giving a plan for a flower garden, with a list of plants, and reference to their proper site in every border, clump or parterre. Such it is in contemplation to publish in the Farmer at some future period; for the present, a few general hints must suffice. . . Whatever may be the arrangement decided upon, the plants generally selected for a flower garden are chosen for the beauty of their appearance, for being odoriferous, or for possessing some such distinguishing characteristic. . .

- “If a mixt flower garden, border or clump, be the object in view, particular attention must be given to the selection of sizes, colors, and the different times of flowering. In planting the different clumps, a proportion of ornamental flowering shrubs may, with propriety, be admitted. The herbaceous plants should be such as produce large heads or masses of flowers—an equal number of every color, and so selected that some shall always be in flower during spring, summer, and fall, with as near a proportion of the different colors as possible. All this can be effected with a very few flowers, so that none need be deterred from forming a flower garden, or properly distributing the various shades of color, under the impression that many plants are absolutely requisite to effect it. Much more regularity, and greater harmony in colors, may be effected by a select few, than by introducing a great number of sorts into one clump. For then a less distinctive or marked character would be the result. There should be a proper system decided upon before a single plant is planted, which will prevent the border or clump from appearing a heterogeneous mass, without meaning, without taste or design. In planting ‘the mingled flower garden,’ it is essential that the separate parts should, in their appearance, constitute a whole; and whatever be the ground plan, it will be no barrier, if proper attention be given to the mode of arranging the plants. . .

- “For what is termed the ‘select flower garden,’ a different style of planting is adopted—planting only one species of plant in each bed, such as tulips, hyacinths, dahlias, ranunculus, anemonies, pinks, &c. &c. This mode of planting is very simple, all that is requisite being only to plant them in beds of carefully prepared soil, and mix the colors as far as possible.”

- Sayers, Edward, 1838, The American Flower Garden Companion (1838: 13–16, 127–29, 130–31)[38]

- “The principal object of the ‘Flower garden’ being to please the eye, it should in every department have a clean and healthy appearance, which greatly facilitates the health and growth of the plants and flowers that it contains. . .

- “The principal object to be considered in laying out the flower garden, is the extent and location of the ground, and the taste of the owner.

- “At country residences, where a large extent is appropriated to this department, many convenient and pleasing appendages can be judiciously introduced; as rustic arbors, rustic seats, and rockery; and if water can be connected, it always gives a good effect. All such appendages, I recommend to be constructed in as natural a manner as possible. . .

- “In many cases, the flower garden will have a pleasing appearance, when various figures are cut in a well kept grass plat, where ease should invariably be attended to.

- “In laying out flower gardens, great care should always be taken, that there is a regular proportion of the beds and walks in the different departments; for it will have a bad effect if any thing is cramped. The walks should if possible be wide enough for two persons to walk abreast, in order to give a social effect, which should always be the first consideration in the flower garden. The beds should also be well proportioned, and not too much cut up into small figures, which when bordered with box edging, have the appearance of so many figures formed for the amusement of children more than for the purpose of growing flowers. . .

- “The manner of planting may be simply stated in a few words, combining trees, shrubs and flowers. . .

- “The flower garden attached to city residences, —when well managed, —embraces many useful features relative to health and pleasure, and in every way conveys to the proprietor a moral lesson in natural history of the most refined nature. I trust that every intelligent person is aware that the continual working of the ground, attached to city residences, is, in every way, conducive to the health of the inmates, by dispelling and rectifying the impure vapor, arising from smoke and other causes, that condenses and settles on the surface of the ground; which is purified if the earth is frequently turned up; and, in conjunction with this, the benefit arising is of common interest, in proportion to the quantity of ground kept in such order, in any city or town. . .

- “The plan of the garden I recommend to be such as to give ease with variety; so as to accommodate various plants and shrubs; the walks to be of clean gravel, with an edging of box or neat dwarf plants—as the Thrift, Dwarf Iris, Moss pink, and such like. . .

- “In laying out flower gardens, let them be so managed that many kinds of flowering shrubs may be introduced; for this purpose beds should be appropriated. The most common error is laying out city gardens is, that they are too much cut up into small figures, and consequently shrubs, so essential to give a variety, cannot be admitted. Nothing should be cramped, but every thing should have an open, easy appearance, in the flower garden. . .

- “Native plants and flowers are those which are found growing spontaneously, without the aid of culture; perhaps no country has a finer or more numerous collection of hardy flowering plants than the United States; indeed, no collection can be said to be complete, without the American Flora, which has engaged the attention of horticulturists to such an extent in Europe, that grounds have been prepared and adapted for American plants; and it is greatly to be hoped that the present good taste for gardening in this country, will be the means of introducing the many pretty varieties of flowers that are to be found in every part of the Union; particularly the beautiful Azelias, Kalmias, Rhododendrons, and many others, that are much wanted in the flower garden.

- “It would far exceed my prescribed limits to give a descriptive list of the many varieties of plants that deserve a place in the native flower garden. I have, therefore, given a list of those which most deserve notice; and, as in every section of this country, there are to be found native plants adapted to their peculiar situation, I recommend that such as are pretty be selected and planted as similar as possible to their natural location. This method will at once create a taste for cultivating native plants and flowers, and facilitate a practical knowledge of their habits and location, in a natural state. Nothing can be a more inviting appendage to the country residence, where a sufficient quantity of ground can be appropriated, than a plot converted into an American flower garden; especially on the banks of rivers and streams, as those of the Hudson, and many others, from which water might be introduced. In such situations, every variety of native plants might be commodiously planted, and grown to a high state of perfection.

- “The best method of laying out such gardens, is to manage the water so as to form a narrow strip or stream two or three feet deep, and if a natural stream can be hand, the better: at the end an artificial pond might be made at a trifling expense, for growing the Water Lily, and Native Aquatics; and also for the purpose of introducing gold and silver fishes.

- “The south margin of the stream might be advantageously planted with native flowering shrubs, as the Azelias, Kalmias, Spireas, and those that are found growing in such situations: the margin of the pond should be planted with drooping willows and trees of a pendulous habit for shade, under which a rustic seat might be properly placed for the accommodation of those who desire to view the sporting fishes, and other interesting objects by which they are surrounded. Attached to the pond or streams, I recommend a well arranged grass plot, with a few figures cut therein, which should be planted with native herbaceous plants, and dwarf shrubs. On the margin of the grass plot, a serpentine or some well contrived walk, bordered with shrubbery, leading to a rockery, of a semicircular form on the north side, and almost straight on the south. A rockery so situated, might be planted with various perennial and annual plants, and dwarf shrubs, which would there find a natural aspect and location.”

- W., M. A., February 1840, “On Flower Beds” (Magazine of Horticulture 6: 51–52)[39]

- “The laying out of a flower knot, or system of beds in a flower garden, is one of the first feats in which the young gardener undertakes to show off his abilities; and being one which affords the most ample scope for the play of fancy, is therefore, perhaps, the one in which he is most likely to manifest the display of a bad taste. Even where the design is of the most happy conception, and the plotting beautiful upon paper, the difficulty of defining and preserving accurately the outline of the figure, when practically applied, will often quite destroy the anticipated pleasing effect. Edge-boards of wood, so thin as to be easily bent to the required form, are commonly the first material employed. These soon warped out of shape, or quickly rot, and impart a deleterious principle to the soil in contact with them; and a very common fault is to have them too wide, so that the plants in the beds suffer from drought, while the paths between them resemble gutters more than walks for pleasure.”

- Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), May 1840, “On the Cultivation of Annual Flowers” (Magazine of Horticulture 6: 186–87)[40]

- “In the two following plans. . . we have shown the manner in which flower gardens may be laid out, either for the cultivation of a miscellaneous collection of bulbs, perennials and annuals, a collection of perennials and annuals together, a collection of annuals and green-house and frame plants turned out of the pots into the soil, or for a collection of annuals alone. The situation decided upon should be, if possible, near to or in front of the green-house or conservatory, or, if there are neither of these attached to the garden, near to the house, where it can be seen from the drawing-room or library; but, as in most gardens, there is space afforded in front of the green-house, that is certainly the best place. Its size may be regulated altogether by the taste and desire of the owner; it may be the full length of the conservatory and in the form of a parallelogram, or it may be exactly a square, or its form may be regulated by the space, aspect, &c.

- “In the two plans annexed, we have supposed the flower garden to be situated directly in front of the green-house and to be just the same length, (thirty-two feet, the ordinary length of a common sized house,) and width; the beds should be laid out with care, as on their precision much of their beauty depends: the beds may be surrounded with box edging, and gravel walks between, or they may be edged with what we have found to answer a good purpose, Iceland moss. This forms a perpetual green, and, if kept neatly trimmed, is full as desirable an edging around such common beds as the box: supposing this to be ALL completed, we next come to the planting of beds. This, as we have just observed, may be devoted wholly to annuals, to annuals and perennials, and to both, with the addition of tender plants, such as verbenas, &c. &c.; but we shall at present speak of them as only to be filled with annuals.” [Figs. 8 and 9]

- Buist, Robert, 1841, The American Flower Garden Directory (1841: 9–13)[41]

- “The Flower Garden is chiefly devoted to the cultivation of showy flowering plants, shrubs, and trees, either natives of this country or those of a foreign clime: it is a refined appendage to a country-seat, ‘suburban’ villa, or city residence; every age has had its principles of taste, and every country its system of gardening. . . . The Italian style is characterized by broad terraces and paralléle walks, having the delightful shade and agreeable fragrance of the orange and the myrtle. Terraces may be advantageously adopted to surmount steep declivities; and, if judiciously laid out, would convert a steril [sic] bank into a beautiful promenade or choice flower garden.

- “The French partially adopt the above system, interspersing it with parterres and figures of statuary work of every character and description. When such is well designed and neatly executed, it has a lively and interesting effect; but now the refined taste says these vagaries are too fantastic, and entirely out of place. A late writer says of Dutch gardening, that it ‘is rectangular formality:’ they take great pride in trimming their trees of yew, holly, and other evergreens, into every variety of form, such as mops, moons, halberds, chairs, &c. In such a system it is indispensable to order that the compartments correspond in formality, nothing being more offensive to the eye than incongruous mixtures of character.

- “The beauty of English gardening consists in an artful imitation of nature, and is consequently much dependent on aspect and locality. It is a desideratum where wood and water can be combined with the flower garden, and the practical eye can dispose of an object to advantage by interspersing shrubbery and walks, that the combined objects form an agreeable whole. They are not to be disposed with a view to their appearance in a picture, but to the use and enjoyment of them in real life.

- “We will now endeavour to give an explicit exposition of a system adapted to our variable climate of extreme heat and excessive cold. Where choice of aspects can be obtained, preference should be given to a south-east or east; but, if not, south or south-west, and, if possible, sheltered by rising ground or full-grown woods from the north-west and north. . . A good soil is the sure foundation on which to rear the grand floral superstructure, and the most genial is a sandy loam. . . With many, the arrangement of a flower garden is rather a matter for the exercise of fancy, than one calling for the application of refined taste. . . But, in commencing these operations, a design should be kept in view that will tend to expand, improve, and beautify the situation; not, as we too frequently see it, the parterre and borders with narrow walks up to the very household entrance: such is decidedly bad taste, unless compelled for want of room. For perspicuity, admit that the area to be enclosed should be from one to three acres, a circumambient walk should be traced at some distance within the fence, by which the whole is enclosed; the inferior walks should partly circumscribe and intersect the general surface in an easy serpentine and sweeping manner, and at such distances as would allow an agreeable view of the flowers when walking for exercise. Walks may be in breadth from three to twenty feet, although from four to ten feet is generally adopted. . . The outer margin of the garden should be planted with the largest trees and shrubs: the interior arrangement may be in detached groups of shrubbery and parterres. In order that the whole should not partake of an uniform and graduated character, it should be broken and diversified by single trees plantedin the turf, or arising in scattered groups from a base of shrubs. In some secluded spot rock-work or a fountain, or both, may be erected. . . The undertaking, when well completed, will present a field of varied and interesting study, and more than compensate for the labour and expense bestowed upon it. If it is desired that the flower garden should be a botanical study, there should be some botanical arrangement adopted.

- “The Linnean system is the most easily acquired. A small compartment laid out in beds might contain plants of all the twenty-four classes, and a few of all the hardy orders, which do not exceed one hundred. Or, to have their natural characters more assimilated, the Jussieuean system could be carried into effect by laying down a grass plat to any extent above one quarter of an acre, and cut therein small figures to contain the natural families, which if hardy plants we do not supposed would exceed one hundred and fifty. . . All the large divisions should be intersected by small alleys, or paths, about one and a half or two feet wide. When there is not a green-house attached to the flower garden, there should be at least a few sashes of framing or a forcing pit to bring forward early annuals, &c., for early blooming. These should be situate in some spot detached from the garden by a fence of Roses, trained to trellises, Chinese Arbour vitae, Privet, or even Maclura makes excellent fences.”

- Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), January 1844, “Retrospective View of the Progress of Horticulture for 1843” (Magazine of Horticulture 10: 9)[42]

- “In planting flower gardens, artistical effect is but little attended to. It is here, however, that amateurs often have the means of making a great deal out of a small spot of ground; lawns and pleasure grounds are only the accompaniments of the villa, while the flower garden is an appendage to almost every residence. To lay it out and plant in a judicious manner is consequently an object of importance.”

- Loudon, Jane, 1845, Gardening for Ladies (1845: 209–11)[43]

- “FLOWER-GARDENS embrace a subject on which a volume might be written without exhausting it; but the present article will be confined to a few general observations, applicable in every case; and to a short notice of the different kinds of flower-gardens which have been, or are, in most general use.

- “All flower-gardens, to have good effect, ought to be symmetrical; that is, they ought to have a centre, which shall appear decided and obvious at first sight, and sides; and all the figures or compartments into which the garden is laid out, ought to be in some way or other so connected with the centre as not to be separable from it, without injuring the general effect of the garden. All the beds and borders ought to have one general character of form and outline; that is, either curved, straight, or composite lines ought to prevail. The size of the beds ought also never to differ to such an extent, as to give the idea of large beds and small ones being mixed together; and the surface of the garden ought to be of the same character throughout; that is, it ought not to be curvilinear on one side of the centre, and flat or angular on the other. In the planting flower-gardens the same attention to unity ought to be kept in view. One side ought not to be planted with tall-growing plants, and the other with plants of low growth; nor one part with evergreens, whether ligneous or herbaceous, and the other part with annuals or bulbs. Flower-gardens which are intended to be ornamental all the year, ought to have a large proportion of evergreen herbaceous plants distributed regularly all over them; such as Pinks, Sweet Williams, Thrift, Saxifrages, and intermixed with very low evergreen shrubs. . . Flower-gardens which are intended to be chiefly ornamental in spring, ought to be rich in bulbs and early-flowering shrubs. . . those that are intended to be chiefly ornamental in summer, should be rich in annuals; and those that are to be in perfection in autumn, in Dahlias. Flower-gardens on a large scale never look so well as when the spaces between the beds are of turf; but those on a small scale may have the spaces between the beds of gravel, and the beds edged with box. . .

- “All the different kinds of flower-gardens may be reduced to the following:

- The French garden, or parterre, is formed of arabesques, or scrollwork, or, as the French call it, embroidery of Box, with plain spaces of turf or gravel, the turf prevailing. The Box is kept low, and there are but very few parts of the arabesque figures in which flowers or shrubs can be introduced. Those plants that are used, are kept in regular shape by cutting or clipping, and little regard is had to flowers; the beauty of these gardens consisting in the figures of the arabesques being kept clear and distinct, and in the pleasing effect produced on the eye by masses of turf, in a country where verdure is rare in the summer season. These embroidered or arabesque gardens originated in Italy and France, and they are better adapted for warm climates than for England: they are, indeed, chiefly calculated for being seen from the windows of the house, and not for being walked in, like English flower-gardens.

- “The ancient English flower-garden is formed of beds, connected together so as to form a regular or symmetrical figure; the beds being edged with Box, or sometimes with flowering plants, and planted with herbaceous flowers, Roses, and one or two other kinds of low flowering shrubs. The flowers in the beds are generally mixed in such a manner, that some may show blossoms every month during summer, and that some may retain their leaves during winter. This kind of garden should be surrounded by a border of evergreen and deciduous shrubs, backed by low trees; and in the centre there should be a sundial, a vase, a statue, or a basin and fountain.