Pleasure ground/Pleasure garden

History

In colonial and federal America, pleasure ground typically denoted an ornamented landscape composed of lawn, trees, shrubs, flowers, intersecting walks, and decorative structures. The designation was employed in reference to both private and public landscapes catering to pleasure and amusement, including the public park or mall and the grounds of wealthy estates. The terms “ornamented grounds” or “ornamental grounds” also were used in reference to these designed landscapes, although with much less frequency than “pleasure ground” or simply “ground.” The single word “ground,” or “grounds,” was used in reference to areas surrounding a house, but did not necessarily distinguish between ornamental and utilitarian or agricultural spaces.

Although defined with slight variations in treatises, the pleasure ground was consistently associated with beauty, order, and the improvement of nature. As such, the feature was promoted frequently as an ideal complement to a well-designed house, as Benjamin Henry Latrobe insisted in 1805 (). Typically located in close proximity to the house, the pleasure ground was visible and easily accessible from prominent rooms of the house. British landscape designer Humphry Repton occasionally described the pleasure ground as “dressed,” which underscores the term’s reference to an improved part of the landscape (view text).

Pleasure ground was also a term applied to public gardens [Fig. 1]. The term implied both ornament and outdoor enjoyment, explaining its frequent use in relation to urban parks. Assigning the term to such spaces signaled that they were treated aesthetically, designed in accord with principles used in private grounds. This parallel was relevant particularly for spaces that had been formerly utilitarian. For example, when Boston Common was redesigned into a public park, various contemporary speakers described the resulting space as a pleasure ground in order to reaffirm its shift in use from a site for husbandry to one of public amusement and enjoyment.[1] Commons, in fact, typically had been used for activities such as grazing or bivouacking.

The term appears to have come into general use in the late 18th century. It is related to the term pleasure garden, used by such treatise writers as Antoine-Joseph Dezallier d'Argenville (1712) to describe ornamented landscapes that included parterres, groves, grass plots, arbors, fountains, and cascades.[2] The terms were relatively interchangeable in the 19th century, as indicated by Charles Drayton's 1806 use of the phrase “pleasure ground or garden” to describe the designed landscape at The Woodlands near Philadelphia (view text), and by treatise writer Bernard M’Mahon, who in the same year referred to the “Pleasure, or Flower-Garden, or Pleasure-ground”(view text). By the time George William Johnson published his dictionary in 1847, however, pleasure ground had emerged as the preferred of the two terms (view text). Although his definition listed exactly the same features as those catalogued by Dezallier d'Argenville, Johnson chose to associate these with the term “pleasure ground.”

The lack of distinction between pleasure grounds and pleasure gardens resulted from their shared function and shared materials. Both catered to sensual and visual pleasure, and both utilized flowers and shrubs, which were also used in flower gardens and shrubberies. The distinguishing characteristic of the pleasure ground appears to have been its larger size. A flower garden or shrubbery could, for example, be encompassed within a pleasure ground, but not the reverse. A pleasure ground might thus include lawns, woods, and water, in addition to shrubs and flowers. As John Abercrombie and James Mean explained in 1817, the pleasure ground should be a judicious mixture and balance of flower garden, lawn, and shrubbery, in emulation of “the moderation with which nature scatters her ornaments” (view text).

In keeping with the use of the pleasure ground as a display for ornamental plants, a marked interest in shrubs and trees can be detected in numerous accounts of American pleasure grounds. For example, David Meade’s (1793) pleasure ground featured forest and fruit trees; William Hamilton's (1802) pleasure ground at The Woodlands included copses “of native trees, interspersed with artificial groves. . . set with trees collected from all parts of the world”; and Judge William Peters’s (1849) pleasure ground was known for its “rarest trees and shrubs.”

For the pleasure grounds at the National Mall in Washington, DC, Downing proposed a “picturesque” scheme “thickly planted with the rarest trees and shrubs, to give greater seclusion and beauty to its immediate precincts.”[3] In addition to displaying plant material and providing an appropriately ornamented setting for the house, pleasure grounds provided spaces for walks. Englishman Augustus John Foster (1807), for example, attributed the lack of pleasure grounds in Virginia to a lack of appreciation for walking outdoors.

Although the pleasure ground was easily conflated with other ornamental features, it was considered distinct from utilitarian areas of the grounds, such as kitchen gardens. (See, for example, references from J. C. Loudon [1826] and Jane Loudon [1843].) The decoration of pleasure grounds reinforced the distinction between the utilitarian and the ornamental; in 1804 Thomas Jefferson, for example, noted that garden temples were more appropriate to the pleasure ground than to the kitchen garden (view text). Other ornamental structures found in pleasure grounds included summerhouses (also called pleasure houses), trellises, bowers, and rustic seats.

Decorative objects and structures were important not only as ornaments to the pleasure grounds, but also as markers of particular styles, as Jane Loudon argued in 1843 (view text). Loudon and Bernard M’Mahon (1806) distinguished pleasure grounds executed in the ancient style from those done in the modern style. The former was characterized by geometric design and the latter by broad curving sweeps of vegetation assembled in imitation of rural nature.

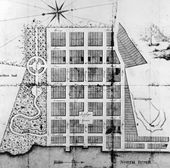

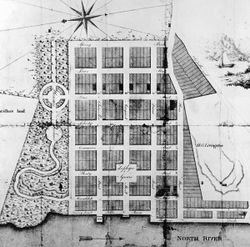

The modern style of pleasure ground described by Loudon and M’Mahon bore a strong resemblance to a park, which also displayed clumps of trees and swatches of grass. Some designers preferred distinct boundaries between the two features. In his 1803 treatise, Repton advocated separating the pleasure ground from the park by a wall that would prevent passers-by from looking into the private realm of the house (view text). In his 1807 plan for the White House, Latrobe proposed that a road divide the adjacent public park from the inner sanctum of the president’s pleasure grounds [Fig. 2]. Devices such as hedges, live fences, stone walls, palisade fences, and iron fences were also proposed as boundary markers.

Other designers obliterated any division between pleasure ground and park. M’Mahon, in his extensive definition of pleasure grounds, argued that the precinct of the pleasure ground might include adjacent fields and parks (view text). To that same end, Downing (1849), like many of his British predecessors, proposed using a ha-ha to blend visually the pleasure ground with the park beyond (view text).

—Anne L. Helmreich

Texts

Usage

- Goelet, Capt. Francis, c. 1750, describing the residence and garden of Edmund Quincy, Boston, MA (quoted in Pearson 1980: 6)[4]

- “. . . about Ten Yards from the House is a Beautiful Cannal, which is Supplyd by a Brook which is well Stockt with Fine Silver Eels, we Cought a fine Parcell and carried them Home and had them drest for Supper, the House has a Beautifull Pleasure Garden Adjoyning it, and on the Back Part the Building is a Beautiful Orchard with fine fruit trees, etc.” [Fig. 3]

- Anonymous, January 28, 1771, describing Vauxhall Garden, New York, NY (New York Gazette, and Weekly Mercury)

- “To be sold at private Sale, the commodious house and large gardens, in the out ward of this city, known by the name of VAUXHALL; the situation extremely pleasant, having a very extensive view both up and down the North River. . . there are 36 lots and a half of ground laid out to great advantage in a pleasure, and kitchen garden, well stock’d with fruit and other trees, vegetables, &c.

- . . . and several summer houses which occasionally may be removed; the whole in extreme good order and repair, well fenced in, very fit for a large family, or to entertain the gentry, &c. as a public garden, &c. The premises are on lease from Trinity Church, sixty one years of which are yet to come.”

- Anonymous, July 6, 1790, “Grays Gardens,” Federal Gazette, and Philadelphia Daily Advertiser (quoted in Beamish 2015: 202)[5]

- “How shall we attempt to describe this enchanting spot, this fairy ground of pleasure and festivity, where new scenes met the eye at every step. The splendid, every where diversified, illumination, the superb fireworks, the distant waterfall, faintly seen through the trees, attracting the attention and pointing itself out by its murmuring sound, the ship union elegantly lighted up, and shining with superior lustre, the artificial island with its farmhouse and garden, these and many other scenes almost pained the eye with delight.”

- Spooner, John Jones, 1793, describing Maycox Plantation, estate of David Meade, Prince George’s County, VA (quoted in Martin 1991: 103)[6]

- “. . . pleasure grounds of David Meade, Esq., of Maycox. . . These grounds contain about twelve acres, laid out on the banks of James river in a most beautifull and enchanting manner. Forest and fruit trees are here arranged, as if nature and art had conspired together to strike the eye most agreeably. Beautiful vistas, which open as many pleasing views of the river.”

- Weld, Isaac, 1799, describing the White House, Washington, DC (1799: 2:47)[7]

- “One hundred acres of ground, towards the river, are left adjoining to the house for pleasure grounds.”

- Ogden, John Cosens, 1800, describing Bethlehem, PA (1800: 13)[8]

- “The sloping banks formed by nature, and the walks by which we mount the hill, prepared by labor, join their varieties, to convert this fertile spot into the appearance of a pleasure garden.”

- Cutler, Manasseh, January 2, 1802, describing The Woodlands, seat of William Hamilton, near Philadelphia (1987: 2:145)[9]

- “We then walked over the pleasure grounds in front and a little back of the house. It is formed into walks, in every direction, with borders of flowering shrubs and trees. Between are lawns of green grass, frequently mowed to make them convenient for walking, and at different distances numerous copse of native trees, interspersed with artificial groves, which are set with trees collected from all parts of the world.” [Fig. 4]

- Jefferson, Thomas, 1804, describing Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, VA (quoted in Nichols and Griswold 1978: 110–11)[10]

- “At the Rocks. . . a turning Tuscan temple. . . proportions of Pantheon, . . . at the Point, . . . build Demosthene’s lantern. . . The kitchen garden is not the place for ornaments of this kind. bowers and treillages suit that better, & these temples will be better disposed in the pleasure grounds.” back up to History

- Latrobe, Benjamin Henry, March 26, 1805, describing a design for a house in Philadelphia, PA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “The design No. I, if no larger in extent as to the ground it occupies than is wished combines as far as I possess the talent to combine them, the separate advantages of an English and a French town residence of a genteel family. My objects in this residence design were: 1. To avoid back buildings, for which the ground is indeed to shallow if a pleasure ground and stables on the Alley, both necessary appendages to a good house, are required.” back up to History

- Drayton, Charles, November 2, 1806, describing The Woodlands, seat of William Hamilton, near Philadelphia, PA (1806: 54)[11]

- “The Approach, its road, woods, lawn & clumps, are laid out with much taste & ingenuity. Also the location of the Stables; with a Yard between the house, stables, lawn of approach or park, & the pleasure ground or garden.” back up to History

- Foster, Sir Augustus John, c. 1807, describing Montpelier, plantation of James Madison, Montpelier Station, VA (1954: 142)[12]

- “There are some very fine woods about Montpellier, but no pleasure grounds, though Mr. Madison talks of some day laying out space for an English park, which he might render very beautiful from the easy graceful descent of his hills into the plains below. The ladies, however, whom I have known in Virginia, like those of Italy generally speaking, scarcely even venture out of their houses to walk or to enjoy beautiful scenery. A high situation from whence they can have an extensive prospect is their delight and in fact the heat is too great in these latitudes to allow of such English tastes to exist in the same degree at least as in the mother country. A pleasure ground, too, to be kept in order, would in fact be very expensive, and all hands are absolutely wanted for the plantation.”

- Latrobe, Benjamin Henry March 17, 1807, describing the White House, Washington, DC (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “My idea is to carry the road below the hill under a Wall about 8 feet high opposite to the center of the president’s house. At this point, I should propose, at a future day to thrown an Arch, or Arches over the road in order to procure a private communication between the pleasure ground of the president’s house and the park which reaches to the river, and which will probably be also planted, and perhaps be open to the public.”

- Ramsay, David, 1809, describing a private garden in Charleston, SC (1809: 2:1230)[13]

- “Another is in St. Paul’s district and was originally formed by William Williamson, but now belongs to John Champneys. It contains twenty-six acres, six of which are in sheets of water and abound in excellent fish; ten acres in pleasure grounds, walks, and banks; the remainder is used for horticultural and agricultural purposes. The pleasure grounds are planted with every species of flowering trees, shrubs, and flowers that this and the neighboring States can furnish; and also with similar curious productions of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Another part contains a great number of fruit trees; especially piccan nut and pear trees, which are ripe in succession from the middle of May to the middle of October.”

- Peale, Charles Willson, c. 1825, describing New York, NY (Miller et al., eds., 2000: 5:248)[14]

- “Walking with Mrs. Peale one evening to take the fresh air at the Battery, in those pleasant gravelly walks skirted with Trees. Adjoining to these pleasure grounds they observed places of entertainment brilliantly lighted up with lamps and to regaile the Ear a variety of Musick.” [Fig. 5]

- Trollope, Frances Milton, 1830, describing the Laurel Mountains in Pennsylvania (1832: 1:276)[15]

- “. . . but I little expected that the first spot which should recal the garden scenery of our beautiful England would be found among the mountains: yet so it was. From the time I entered America I had never seen the slightest approach to what we call pleasure-grounds; a few very worthless and scentless flowers were all the specimens of gardening I had seen in Ohio; no attempt at garden scenery was ever dreamed of, and it was with the sort of delight with which one meets an old friend, that we looked on the lovely mixture of trees, shrubs, and flowers, that now continually met our eyes.”

- Anonymous, 1834—35, describing Kentucky (quoted in Schwaab 1973: 266–67)[16]

- “The dwellings are all commodious and comfortable, and the most of them very far superior to those usually inhabited by farmers. Many of them are surrounded by gardens and pleasure-grounds, adorned with trees and shrubs in the most tasteful manner; and the eye is continually regaled with a beautiful variety of rural embellishment. There is a something substantial as well as elegant in the residence of a farmer of this part of Kentucky; a combination of taste, neatness, comfort, and abundance, which is singularly interesting, and which evinces a high degree of liberality in the use of wealth, as well as great industry in its production.”

- Derby, Ezekiel Hersey, January 1, 1836, “Cultivation and Management of the Buckthorn (Rhamnus Catharticus) for Live Hedges” (Horticultural Register 2: 28)[17]

- “It is now about thirty two years, since I first attempted the formation of a live hedge as a boundary for my own pleasure-grounds.”

- Adams, Nehemiah, 1838, describing the city of Boston, MA (1838: 45)[18]

- “And were cities themselves more generally provided with agreeable pleasure grounds, walks, and gardens, and trees, the temptation and the necessity of resorting to the country would be greatly diminished. And while the greater part of those who reside in cities must reside in them throughout the year, they must have their gardens and their shady walks, within the city.”

- Donaldson, Robert, December 16, 1840, in a letter to Mrs. Edward (Louise) Livingston, describing the joint border of Montgomery Place, country home of Mrs. Edward (Louise) Livingston, and Blithewood, seat of Robert Donaldson, Dutchess County, NY (quoted in Haley 1988: 76)

- “If we buy the stream. . . our pleasure grounds extend to the creek from the Cataract to the River—& a lake for fish formed, with ornamental waterfalls—which would render the places all that could be desired.” [Fig. 6]

- Kirkbride, Thomas S., April 1848, describing the pleasure grounds and farm of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, Philadelphia, PA (American Journal of Insanity 4: 347–52)[19]

- “The pleasure grounds and farm of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, as shown in the accompanying plan, comprise a tract of one hundred and ten acres of well improved land, lying two miles west of the City of Philadelphia, between the Westchester and Haverford roads, on the latter of which is the only gate of entrance.

- “Of this land, forty-one and three-quarter acres constitute the pleasure grounds, which surround the Hospital buildings, and are enclosed by a substantial stone wall, of an average height of ten and a half feet. The remaining sixty-nine and one-quarter acres comprise the farm of the Institution. . .

- “The pleasure grounds of the two sexes are very effectually separated on the eastern side, by the deer-park, surrounded by a high palisade fence. . .

- “In the pleasure grounds of the ladies, is a fine piece of woods, from which the farm is overlooked, as well as both of the public roads passing along the premises, and a handsome district of country beyond.

- “The undulating character of the pleasure grounds throughout, gives them many advantages, and the brick, gravel and tan walks for the ladies, are more than a mile in extent. . .

- “The cultivation of the gardens and the improvement of the pleasure grounds, offer the generality of patients the most desirable forms of labour. It is sufficiently varied, not too laborious, and in some division of it many will engage who could not be induced to assist upon the farm or in any other kind of employment, out of doors. . .

- “If the pleasure grounds are sufficiently extensive it is desirable that the two sexes would have their portions, entirely distinct, although some parts may be used in common, under the superintendence and direction of the proper officer. Without this arrangement certain classes will be much more restricted in out-door exercise than is proper or desirable.” [Fig. 7]

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1849, describing Camac Cottage, near Philadelphia, PA (1849: 58)[20]

- “The house is a picturesque cottage, in the rural gothic style, with very charming and appropriate pleasure grounds, comprising many groups and masses of large and finely grown trees, interspersed with a handsome collection of shrubs and plants; the whole very tastefully arranged.” [Fig. 8]

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1849, describing Belmont, estate of Judge William Peters, near Philadelphia, PA (1849: 42–43)[20]

- “Its proprietor had a most extended reputation as a scientific agriculturist, and his place was also no less remarkable for the design and culture of its pleasure-grounds, than for the excellence of its farm. Long and stately avenues, with vistas terminated by obelisks, a garden adorned with marble vases, busts, and statues, and pleasure grounds filled with the rarest trees and shrubs, were conspicuous features here.” [Fig. 9]

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1849, describing Hyde Park, seat of David Hosack, on the Hudson River, NY (1849: 45–46)[20]

- “But the efforts of art are not unworthy so rare a locality; and while the native woods, and beautifully undulating surface, are preserved in their original state, the pleasure-grounds, roads, walks, drives, and new plantations, have been laid out in such a judicious manner as to heighten the charms of nature.”

- Justicia [pseud.], March 1849, “A Visit to Springbrook,” seat of Caleb Cope, near Philadelphia, PA (Horticulturist 3: 411)[21]

- “The elegant mansion is surrounded with a spacious lawn, kept in a masterly style; and the pleasure-grounds are enclosed by a light iron fence, about half a mile in length, and studded with many varieties of hardy trees, backed by a natural piece of the most majestic woods,—giving a fine sylvan character to the place.”

- Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), December 1849, describing Oatlands, residence of D. F. Manice, Hempstead, NY (Magazine of Horticulture 15: 529)[22]

- “The house is a handsome building, in a kind of castellated gothic, standing about fifty feet from the road, with the conservatory and hothouse, and flower garden on the left,—the kitchen garden and forcing-houses on the right,—and the lawn and pleasure ground, in the rear of the house, separating it from the park.”

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1850, describing Boston Common, Boston, MA (1850: 332–33)[23]

- “856. Public Gardens. . .

- “At Boston there are extensive public pleasure-grounds called the Common, consisting of seventy-five acres, in the very heart of the city. This piece of ground is well laid out, and contains many fine trees. The state-house, and the handsome houses of the city, surround it on three sides.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, August 1851, “The New-York Park” (Horticulturist 6: 346–47)[24]

- “That because it is needful in civilized life for men to live in cities,—yes, and unfortunately too, for children to be born and educated without a daily sight of the blessed horizon,—it is not, therefore, needful for them to be so miserly as to live utterly divorced from all pleasant and healthful intercourse with gardens and green fields. He [Mayor Kingsland] informs them that cool umbrageous groves have not forsworn themselves within town limits, and that half a million of people have a right to ask for the ‘greatest happiness’ of parks and pleasure grounds, as well as for paving stones and gas lights. . .

- “Five hundred acres is the smallest area that should be reserved for the future wants of such a city, now, while it may be obtained. Five hundred acres may be selected between 39th-street and the Harlem river, including a varied surface of land, a good deal of which is yet waste area, so that the whole may be purchased at something like a million of dollars. In that area there would be space enough to have broad reaches of park and pleasure-grounds, with a real feeling of the breadth and beauty of green fields, the perfume and freshness of nature.”

Citations

- Cobbett, William, 1802, remarks on “Notes Adapting the Rules of the Treatise to the Climates and Seasons of the United States of America,” in A Treatise on the Culture and Management of Fruit Trees (Forsyth 1802: 151)[25]

- “To those American gentlemen, who have land to lay out in pleasure grounds, and most of them have land, which might, at a very little expence, be so disposed of, I would beg leave to recommend the perusal, and, indeed, the study, of the late Lord Orford’s celebrated work on ‘Modern Gardening, and laying out of pleasure grounds, parks, farms, ridings, &c. &c. illustrated by Descriptions.’ This work is a most excellent guide in the study of the higher order of gardening, and very far surpasses what has been written by Gilpin, and, indeed, by all other authors on the subject.”

- Repton, Humphry, 1803, Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1803: 8, 99, 180)[26]

- “The pleasure ground, immediately near the house, is separated from the park by a wall, against which the earth is every where laid as before described, so as to carry the eye over the heads of persons who may be walking in the adjoining foot-path. This wall not only hides them from the house, but also prevents their overlooking the pleasure ground. . .

- “This line of separation [between the ground exposed to cattle and the ground annexed to the house] being admitted, advantage may be easily taken to ornament the lawn with flowers and shrubs, and to attach to the mansion that scene of 'embellished neatness,' usually called a Pleasure Ground. . .

- “I would make the dressed pleasure ground to the right and left of the house, in plantations, which would skreen the unsightly appendages, and form the natural division between the park and the farm, with walks communicating to the garden and the farm.” back up to History

- M’Mahon, Bernard, 1806, American Gardener’s Calendar (1806: 55–56)[27]

- “THE district commonly called the Pleasure, or Flower-Garden, or Pleasure-ground, may be said to comprehend all ornamental compartments, or divisions of ground, surrounding the mansion; consisting of lawns, plantations of trees and shrubs, flower compartments, walks, pieces of water, &c. whether situated wholly within the space generally considered as the Pleasure-Garden, or extended to the adjacent fields, parks, or other out-grounds.

- “In designs for a Pleasure-ground, according to modern gardening; consulting rural disposition, in imitation of nature; all too formal works being almost abolished, such as long straight walks, regular intersections, square grass-plats, corresponding parterres, quadrangular and angular spaces, and other uniformities, as in ancient designs; instead of which, are now adopted, rural open spaces of grass-ground, of varied forms and dimensions, and winding walks, all bounded with plantations of trees, shrubs, and flowers, in various clumps; other compartments are exhibited in a variety of imitative rural forms; such as curves, projections, openings, and closings, in imitation of a natural assemblage; having all the various plantations and borders, open to the walks and lawns. . . .

- “In designs for a Pleasure-ground, according to modern taste, a tract of ground of any considerable extent, may have the prospect varied and diversified exceedingly, in a beautiful representation of art and nature, as that in passing from one compartment to another, still new varieties present themselves, in the most agreeable manner; and even if the figure of the ground is irregular, and the surface has many inequalities, the whole may be improved without any great trouble of squaring or levelling; for by humouring the natural form, you may cause even the very irregularities and natural deformities, to carry along with them an air of diversity and novelty, which fail not to please and entertain most observers.” back up to History

- Abercrombie, John, with James Mean, 1817, Abercrombie’s Practical Gardener (1817: 337–38, 453, 460)[28]

- “The lines of distinction between the Flower Garden, the Shrubbery, and the Pleasure Ground, can neither be positively marked, nor constantly observed, in treating the subjects which may seem to fall under one of these heads more properly than under either of the others.

- “The flowering shrubs connect the two former. For instance, can there be such an exact partition between the Flower Garden and the Shrubbery, as would destroy their communication, while the plant which bears the beautiful rose belongs, in a catalogue of names, to the latter department? Or can we prevent the Pleasure Ground from running into the Flower Garden and Shrubbery, so as scarcely to know where one begins and the other ends, as long as a Pleasure Ground, with the most happy diversity of lawns, wood, and water, would be incomplete without flowers and shrubs?

- “The substantial difference between the two former Flower Garden and Shrubbery], lies in the proportion in which the two classes of plants are cultivated: hence, where a great preponderance of plants without woody stems display their bloom, the characteristics of a Flower Garden seem obvious enough: if another spot is almost covered with clumps of shrubs, and merely dotted with a few creeping flowers, it will be termed, without hesitation, a Shrubbery.

- “The most essential point of separation between a Flower Garden and a Pleasure Ground seems to turn on the extent of the place. To cover twenty acres with mere flowering plants, producing nothing esculent in the root, leaves, or fruit, would be puerile and ridiculous, as it would exceed the moderation with which nature scatters her ornaments; hence as the surface to be dressed, even for pleasure, widens, plots of grass are interposed, clumps of shrubs, and other circumstances of relief; and if the limits of the ground are yet farther removed, pastured lawns and groves of timber show that utility and beauty of effect may harmonize. On the other hand, if a circumscribed garden were so occupied by mown grass as to leave but a few feet for the florist, it would not be a Pleasure Ground. . .

- “A PLEASURE GROUND is an extensive garden laid out in a liberal taste, and embellished after nature. At the sight of such a garden, fortunately placed and judiciously improved, in which the cultivator has availed himself of every advantage which the immediate site and surrounding landscape presents, almost every mind concurs in associating the idea of a garden with a seat of happiness. When the romantic illusions of a first view are dissolved, to enjoy the beauties of such a place is one of the purest gratifications. . .

- “While the Kitchen Garden is concealed by buildings or plantations, the Flower Garden and Pleasure Ground should stand conspicuously attached to the family-residence.” back up to History

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826: 451, 1021)[29]

- “2355. To unite the agreeable with the useful is an object common to all the departments of gardening. The kitchen-garden, the orchard, the nursery, and the forest, are all intended as scenes of recreation and visual enjoyment, as well as of useful culture; and enjoyment is the avowed object of the flower-garden, shrubbery, and pleasure-ground. . .

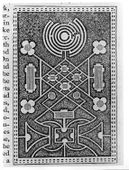

- “7264. The pleasure-ground is a term applied generally to the kept ground and walks of a residence. Sometimes the walk merely passes, in a winding direction, through glades and groups of common scenery, kept polished by the scythe, and from whence cattle, &c. are excluded. At other times it includes a part of, or all the scenes above mentioned; and may include several others, as verdant amphitheaters, labyrinths. . . a Linnaean, Jussieuean, American, French, or Dutch flower-garden, a garden of native, rock, mountain, or aquatic plants, picturesque flower-garden, or a Chinese garden, exhibiting only plants in flower, inserted in the ground, and removed to make room for others when the blossom begins to fade, &c.” [Fig. 10]

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828: 2:n.p.)[30]

- “PLEAS'URE-GROUND, n. Ground laid out in an ornamental manner and appropriated to pleasure or amusement. Graves.”

- Walsh, Alexander, March 1841, “Remarks on Ornamental Gardening” (New England Farmer 19: 308)[31]

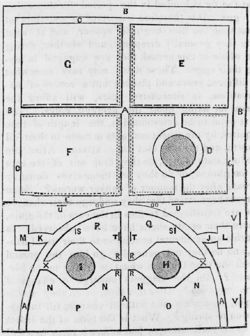

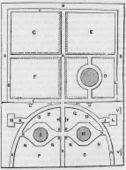

- “The garden and pleasure ground I would describe, is of an oblong form, 165 feet by 120 feet, with one end next the north side of the house, (fig. 1.) A walk 5 feet in width, A A, of a semi-elliptical form, passes from north hall door to the principal rear building on the west, extending in its course to the north 60 ft.; a walk of 5 ft. in width extends through the centre from south to north, 159 ft. A A, and is crossed at right angles by another of the same width 47 feet from the north edge of the elipsis; walks of 4 ft. width C C C C, surround the four squares. The walks graveled; formed rising at the centre to the height of the beds, with a descent each side, of an inch and a half to the border, which border is composed of bricks laid edgewise, the outer side flush with the soil, the inner side an inch and a half above the lowest part of the walk. H and I two mounds 12 inches diameter, 3 feet 6 inches high, enclosed by octagons, leaving a walk 4 feet in the narrowest part, with openings of 6 feet to the centre walk and elipsis; the mounds enclosed with brick, placed endwise, inclining to the centre, and sunk 3 inches in the ground; the enclosure filled with soil; each mound has growing in its centre an evergreen tree. H covered with evergreen periwinkle, Vica minor, and I covered with variegated periwinkle, Vica minor fl. alba.” [Fig. 11]

- Loudon, Jane, 1843, Gardening for Ladies (1843: 239–40)[32]

- “PLEASURE-GROUND is that portion of a country residence which is devoted to ornamental purposes, in contradistinction to those parts which are exclusively devoted to utility or profit, such as the kitchen-garden, the farm, and the park. In former times, when the geometrical style of laying out grounds prevailed, a pleasure-ground consisted of terrace-walks, a bowling-green, a labyrinth, a bosquet, a small wood, a shady walk commonly of nut-trees, but sometimes a shady avenue, with ponds of water, fountains, statues, &c. In modern times the pleasure-ground consists chiefly of a lawn of smoothly-shaven turf, interspersed with beds of flowers, groups of shrubs, scattered trees, and, according to circumstances, with a part or the whole of the scenes and objects which belong to a pleasure-ground in the ancient style. The main portion of the pleasure-ground is always placed on that side of the house to which the drawing-room windows open; and it extends in front and to the right and left more or less, according to the extent of the place; the park, or that part devoted exclusively to pasture and scattered trees, being always on the entrance front. There is no limit to the extent either of the pleasure-ground or the park, and no necessary connection between the size of the house and the size of the pleasure-ground. . . In small places of an acre or two, the most interesting objects which may be introduced in a pleasure-ground, are collections of trees, shrubs, and herbaceous plants, which may always be arranged to combine as much picturesque beauty and general effect as if there were only the few kinds of trees and shrubs planted which were formerly in use in such scenes.” back up to History

- Johnson, George William, 1847, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening (1847: 465)[33]

- “PLEASURE-GROUND is a collective name for that combination of parterres, lawns, shrubberies, waters, arbours, &c. which are noticed individually in these pages. One observation may be applied to all—let congruity preside over the whole. It is a great fault to have any one of those portions of the pleasure ground in excess; and let the whole be proportioned to the residence. It is quite as objectionable to be over-gardened as to be over-housed. Above all things eschew what has aptly been termed gingerbread-work. Nothing offends a person of good taste so much as the divisions and sub-divisions we are sometimes compelled to gaze on ‘with an approving smile.’” back up to History

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, October 1848, “A Talk About Public Parks and Gardens” (Horticulturist 3: 156)[34]

- “Make the public parks or pleasure grounds attractive by their lawns, fine trees, shady walks and beautiful shrubs and flowers, by fine music, and the certainty of ‘meeting everybody,’ and you draw the whole moving population of the town there daily.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1849, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849: 34, 82, 88)[20]

- “Previous artists had confined their efforts within the rigid walls of the garden, but [William] Kent, who saw in all nature a garden-landscape, demolished the walls, introduced the ha-ha, and by blending the park and the garden, substituted for the primness of the old inclosure, the freedom of the pleasure-ground. . .

- “In pleasure-grounds, while the whole should exhibit a general plan, the different scenes presented to the eye, one after the other, should possess sufficient variety in the detail to keep alive the interest of the spectator, and awaken further curiosity.

- “. . . while, in a more elevated and enlightened taste, we are able to dispose them [trees] in our pleasure-grounds and parks, around our houses, in all the variety of groups, masses, thicket, and single trees, in such a manner as to rival the most beautiful scenery of general nature.” back up to History

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, June 1850, “Our Country Villages” (Horticulturist 4: 540)[35]

- “After such a village was built, and the central park planted a few years, the inhabitants would not be contented with the mere meadow and trees, usually called a park in this country. By submitting to a small annual tax per family, they could turn the whole park, if small, or considerable portions, here and there, if large, into pleasure-grounds. In the latter, there would be collected, by the combined means of the village, all the rare, hardy shrubs, trees and plants usually found in the private grounds of any amateur in America. Beds and masses of everblooming roses, sweet-scented climbers and the richest shrubs would thus be open to the enjoyment of all during the whole growing season. Those who had neither the means, time, nor inclination to devote to the culture of private pleasure-grounds, could thus enjoy those which belonged to all. Others might prefer to devote their own garden to fruits and vegetables, since the pleasure-grounds, which belonged to all, and which all would enjoy, would, by their greater breadth and magnitude, offer beauties and enjoyments which few private gardens can give.”

Images

Inscribed

Pierre Pharoux, “Plan of Tivoli Laid Out into Town Lots” [detail], NY, 1795. “Pleasure ground” is inscribed on the left of the plan.

J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, "The pleasure-ground", in An Encyclopaedia of Gardening, 4th ed. (1826), 1021, fig. 719.

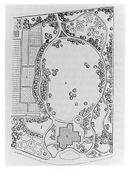

Thomas S. Sinclair, “Plan of the Pleasure Grounds and Farm of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane at Philadelphia,” in Thomas S. Kirkbride, American Journal of Insanity 4, no. 4 (April 1848): pl. opp. 280. “Gentlemens Pleasure Grounds” to the far right of the plan. “Ladies Pleasure Grounds” just right of the hospital buildings.

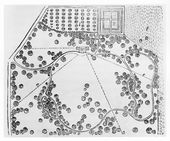

Anonymous, “Plan of a Suburban Villa Residence” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), 118, fig. 26. “Pleasure ground” is marked as b.

A. J. Downing, Plan Showing Proposed Method of Laying Out the Public Grounds at Washington, 1851.

A. J. Downing, Plan Showing Proposed Method of Laying Out the Public Grounds at Washington, 1851. Manuscript copy by Nathaniel Michler, 1867.

A. J. Downing, Plan Showing Proposed Method of Laying Out the Public Grounds at Washington [detail], 1851. Manuscript copy by Nathaniel Michler, 1867.

Associated

John Drayton, A View of the Battery and Harbour of New York, and the Ambuscade Frigate, 1794.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Sketch plan for landscaping the grounds of the President’s House, c. 1802—5.

Alexander Jackson Davis, View in Grounds at Blithewood, Seat of Robt. Donaldson, Dutchess Co. Hud[son] riv[er]. N.Y., 1840.

Anonymous, “View in the Grounds at Hyde Park” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), 45, fig. 1.

Anonymous, “Kenwood, Residence of J. Rathbone, Esq. near Albany, N.Y.” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), 50, fig. 9.

Anonymous, “Belmont Place, near Boston, the seat of J. P. Cushing, Esq.” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), pl. opp 54, fig. 10.

Anonymous, “Mr. Dunn’s Cottage, Mount Holly, N. J.” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), pl. opp. 54, fig. 11.

Anonymous, “View in the Grounds of James Arnold, Esq.” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), pl. opp. 57.

Anonymous, “The Seat of George Sheaff, Esq.” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), pl. between 58 and 59, fig. 12.

Anonymous, “Mrs. Camac’s Residence,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), pl. between 58 and 59, fig. 13.

Anonymous, “Plan of the foregoing grounds as a Country Seat, after ten years’ improvement,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), 114, fig. 24.

Anonymous, “Plan of a Mansion Residence, laid out in the natural style” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), 115, fig. 25. Pleasure grounds are at g and h.

Attributed

Anonymous, “Lemon Hill,” in M. M. Ballou, ed., Ballou’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion 8, no. 19 (May 12, 1855): 297.

Notes

- ↑ Also see A. J. Downing’s writings between 1850 and 1851 about public parks and his plans for the National Mall in Washington, DC. The latter included a pleasure ground in front of the Smithsonian Institution, to be filled with ornamental plantings and a monumental park.

- ↑ A.-J Dézallier d'Argenville, The Theory and Practice of Gardening, trans. John James (1712; repr., Farnborough, England: Gregg International, 1969), 1-2, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Therese O’Malley, “‘A Public Museum of Trees’: Mid-Nineteenth Century Plans for the Mall,” in The Mall in Washington, 1791–1991, ed. Richard Longstreth (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1991), 68, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Danella Pearson, “Shirley-Eustis House Landscape History,” Old-Time New England 70 (1980), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anne Beamish, “Enjoyment in the Night: Discovering Leisure in Philadelphia’s Eighteenth-Century Rural Pleasure Gardens,” Studies in the History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes 35, no. 3 (2015): 198–212, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Peter Martin, Pleasure Gardens of Virginia: From Jamestown to Jefferson (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Isaac Weld, Travels through the States of North America and the Provinces of Upper and Lower Canada, during the Years 1795, 1796, and 1797, 2 vols. (London: John Stockdale, 1799), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John C. Ogden, An Excursion into Bethlehem & Nazareth, in Pennsylvania, in the Year 1799 (Philadelphia: Charles Cist, 1800), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Parker Cutler, Life, Journals, and Correspondence of Rev. Manasseh Cutler, LL.D. (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1987), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Frederick Doveton Nichols and Ralph E. Griswold, Thomas Jefferson, Landscape Architect, (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1978), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Drayton, “The Diary of Charles Drayton I, 1806,” Drayton Hall: A National Historic Trust Site, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Sir Augustus John Foster, Jeffersonian America, Notes on the United States of America Collected in the Years 1805–1806–1807 and 1811–1812, ed. Richard Beale Davis (San Marino, CA: Huntington Library, 1954), view on Zotero.

- ↑ David Ramsay, The History of South-Carolina: From Its First Settlement in 1670, to the Year 1808, 2 vols. (Charleston: David Longworth, 1809), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Lillian B. Miller, et al., eds., The Selected Papers of Charles Willson Peale and His Family, vol. 5, The Autobiography of Charles Willson Peale (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Frances Trollope, Domestic Manners of the Americans 3rd ed., 2 vols. (London: Wittaker, Treacher, 1832), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Eugene L. Schwaab, Travels in the Old South, with the collaboration of Jacqueline Bull (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1973), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Ezekiel Hersey Derby, “Cultivation and Management of the Buckthorn (Rhamnus Catharticus) for Live Hedges,” Horticultural Register, and Gardener’s Magazine 2 (January 1, 1836): 27–29, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Nehemiah Adams, The Boston Common; or, Rural Walks in Cities (Boston: George W. Light, 1838), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas S. Kirkbride, “Description of the Pleasure Grounds and Farm of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, with Remarks,” American Journal of Insanity 4, no. 4 (April 1848): 347–54, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening Adapted to North America. . . , 4th ed. (New York: G. P. Putnam, 1849), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Justicia [pseud.], “A Visit to Springbrook, the Seat of the President of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 3, no. 9 (March 1849): 411–14, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Mason Hovey, “Notes of a Visit to Oatlands, Hempstead, L.I., N.Y., the Residence of D. F. Manice, Esq.,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 15, no. 12 (December 1849): 529–33, view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, new ed. (London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1850), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Andrew Jackson Downing, “The New-York Park,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 6, no. 8 (August 1851): 345–49, view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Forsyth, A Treatise on the Culture and Management of Fruit Trees (Philadelphia: J. Morgan, 1802), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Humphry Repton, Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (London: Printed by T. Bensley for J. Taylor, 1803), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bernard M’Mahon, The American Gardener’s Calendar: Adapted to the Climates and Seasons of the United States. Containing a Complete Account of All the Work Necessary to Be Done. . . for Every Month of the Year. . . (Philadelphia: Printed by B. Graves for the author, 1806), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Abercrombie, Abercrombie’s practical gardener or, Improved system of modern horticulture, with additions by James Mean (London: T. Cadell and W. Davies, 1817), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, 4th ed. (London: Longman et al., 1826), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alexander Walsh, “Remarks on Ornamental Gardening, With a Plan of a Fruit, Flower and Vegetable Garden,” New England Farmer, and Horticultural Register 19, no. 39 (March 31, 1841): 308–9, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jane Loudon, Gardening for Ladies; and Companion to the Flower-Garden, ed. A. J. Downing (New York: Wiley & Putnam, 1843), view on Zotero.

- ↑ George William Johnson, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening, ed. David Landreth (Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1847), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Andrew Jackson Downing, “A Talk About Public Parks and Gardens,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 3, no. 4 (October 1848): 153–58, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Andrew Jackson Downing, “Our Country Villages,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 4, no. 4 (June 1850): 537–41, view on Zotero.