J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon

John Claudius Loudon (8 April 1783 – 14 December 1843) was a Scottish botanist, landscape architect, cemetery designer, and author, as well as the most influential horticultural journalist of his time. Through an extraordinarily prolific publishing career, Loudon raised popular knowledge of and interest in botany, horticulture, and agriculture while shaping contemporary taste in gardens, public parks, and domestic architecture throughout Britain and much of the Western world. [1]

History

As a young man, Loudon worked part-time for nurserymen and landscape gardeners near Edinburgh while pursuing the study of animal husbandry, gardening, and agriculture. On moving to London in 1803, he swiftly established his authority as a practitioner and theorist of landscape gardening, and even dabbled in landscape painting, exhibiting five works at the Royal Academy of Arts between 1804 and 1817. [2] In addition to the study of art, his taste owed much to the reading of classical and modern writers, particularly English poets and aesthetic theorists. Uvedale Price, one of the principal theorists of the picturesque, was especially influential; Loudon later observed, “I believe that I am the first who has set out as a landscape gardener, professing to follow Mr. Price’s principles.” [3] Loudon’s plan for improving the public squares of London through picturesque plantings of trees and shrubs, published in the Literary Journal in 1803, initiated a voluminous outpouring of articles, books, and pamphlets that would occupy him for the rest of his life. [4]

Loudon traveled extensively in order to familiarize himself with the ornamental and agricultural use of land in Britain and continental Europe. Impressed by the productivity of Russian hothouses during a trip to Scandinavia and Eastern Europe (1813-14), he began experimenting with the use of curved iron and glass in innovative hothouse structures that could be adjusted to the changing angle of the sun’s rays [Fig. 1]. [5] In 1819 he visited France, Italy, Switzerland, and the Low Countries to gather material for An Encyclopaedia of Gardening: Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture and Landscape-gardening (1822)— by far the most comprehensive and systematic compendium of gardening information that had been published at the time. In contrast to many of Loudon’s previous publications, which were expensively produced and richly illustrated, the Encyclopaedia of Gardening was a practical guide intended for professional gardeners and middle-class amateurs rather than elite readers. As such, it established a new direction in garden literature that Loudon continued to develop in subsequent publications, such as Encyclopaedia of Cottage, Farm, and Villa Architecture (1833) and The Suburban Gardener and Villa Companion (1838). [6]

Landowners throughout England and Scotland sought Loudon’s advice on improving the grounds of their estates. [7] Following his marriage in 1830, he was greatly assisted by his wife, Jane Webb Loudon, who became an important gardening authority in her own right. [8] In 1826 Loudon launched The Gardener's Magazine — the first periodical devoted solely to horticulture—which aimed “to disseminate new and important information on all topics connected with horticulture and to raise the intellect and the character of those engaged in this art.” [9] Addressed to an expanding middle-class audience, the magazine became an international forum for the exchange of specialized information on scientific discoveries, technological improvements, aesthetic theories, and working designs. [10] An article Loudon published in the magazine in 1832 established the term “Gardenesque” to denote a deliberately artificial style of garden layout that lent itself to botanical study of individual plant specimens, revealing the art of the gardener as well as the beauty of nature [Fig. 2]. [11] Whereas earlier landscape artists had “looked on garden scenery entirely with the eye of a painter and a poet,” Loudon believed that “the modern artist adds to these the eye of the botanist and the cultivator." [12] Loudon’s most important work in the Gardenesque style is the Derby Arboretum (1839-41) — generally considered England’s first public park — which he designed with over one thousand different varieties of trees and shrubs. [13] Among Loudon’s numerous horticultural publications, the most ambitious was his copiously illustrated (and financially ruinous) eight-volume “paper arboretum," the Arboretum et Fruticetum Britannicum (1835-1838): a survey of all the trees and shrubs then growing in Britain, which he hoped would spur a taste for arboriculture and the cultivation of a greater variety of trees. [14]

--Robyn Asleson

Texts

Books

An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826, 4th Edition)

J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, 4th ed. (London: Longman et al, 1826) [15]

- Part I, Book I, Chapter III (pp. 26-27)

- “115. The Dutch are generally considered as having a particular taste in gardening, yet their gardens, Hirschfeld observes, appear to differ little in design from those of the French. The characteristics of both are symmetry and abundance of ornaments. The only difference to be remarked is, that the gardens of Holland are more confined, more covered with frivolous ornaments, and intersected with still, and often muddy pieces of water. . . .

- “116. Grassy slopes and green terraces and walks are more common in Holland than in any other country of the continent, because the climate and soil are favourable for turf; and these verdant slopes and mounds may be said to form, with their oblong canals, the characteristics of the Dutch style of laying out grounds.”

- Part I, Book I, Chapter V (pp. 103, 105, 106)

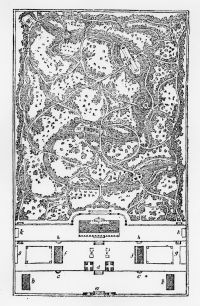

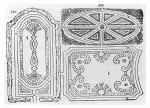

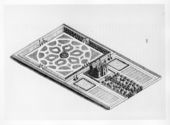

- “478. A plan of a Chinese garden and dwelling. . . . If this plan . . . is really correct, it seems to countenance the idea of the modern style being taken from that of the Chinese. . . . [Fig. 3]

- “482. . . .

- “The first work after a settlement [in North America] is to plant a peach and apple orchard, placing the trees alternately. The peach, being short-lived, is soon removed, and its place covered by the branches of the apple-trees."

- “486. Forest trees. . . . From the Transactions of the Society of Agriculture of New York, we learn, that hawthorn hedges and other live fences are generally adopted in the cultivated districts; but the time is not yet arrived for forming timber-plantations."

- Part II, Book III, Chapter I (pp. 284, 285, 296)

- “1407. Of flower-pots there are several species and many varieties.

- “The common flower-pot is a cylindrical tapering vessel of burnt clay, with a perforated bottom, and of which there are ten British sorts, distinguished by their sizes thus. . . .

- “Common flower-pots are sold by the cast, and the price is generally the same for all the 10 sorts; two pots or a cast of No. 1, costing the same price as eight pots, or a cast of No. 11.

- “The pot for bulbous roots is narrower and deeper than usual.

- “The pot for aquatics should have no holes in the bottom or sides.

- “The pot for marsh-plants should have three or four small holes in the sides about one third of the depth from its bottom. This third being filled with gravel, and the remainder with soil, the imitation of a marsh will be attended with success.

- “The stone-ware pot may be of any of the above shapes, but being made of clay, mixed with powdered stone of a certain quality, is much more durable.

- “The glazed pot is chiefly used for ornament; they are generally glazed green, but, for superior occasions, are sculptured and painted, or incrusted, &c.

- “1408. The propagation-pot . . . has a slit in the side, from the rim to the hole in the bottom, the use of which is to admit a shoot of a tree for propagation by ringing in the Chinese manner. . . .

- “The square pot is preferred by some for the three smallest sizes of pots, as containing more earth in a given surface of shelf or basis; but they are more expensive at first, less convenient for shifting, and, not admitting of such perfection of form as the circle, do not, in our opinion, merit adoption. They are used in different parts of Lombardy and at Paris.

- “The classic pot is the common material formed into vases, or particular shapes, for aloes and other plants which seldom require shifting, and which are destined to occupy particular spots in gardens or conservatories, or on the terraces and parapets of mansions in the summer season.

- “The Chinese pot is generally glazed, and wide in proportion to its depth; but some are widest below, with the saucer attached to the bottom of the pot, and the slits on the side of the pot for the exit or absorption of the water. Some ornamental Chinese pots are squared at top and bottom, and bellied out in the middle.

- “The French pot, instead of one hole in the centre of the bottom to admit water, has several small holes about one eighth of an inch in diameter, by which worms are excluded. . . .

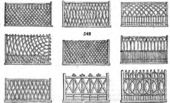

- “1412. The plant-box . . . is a substitute for a large pot; it is of a cubical figure, and generally formed of wood, though in some cases the frame is formed of cast-iron, and the sides of slates cut to fit, and moveable at pleasure. Such boxes are chiefly used for orange-trees.” [Fig. 4]

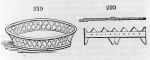

- “1501. The basket-edging (fig. 219.) is a rim or fret of iron-wire, and sometimes of laths; formed, when small, in entire pieces, and when large, in segments. Its use is to enclose dug spots on lawns, so that when the flowers and shrubs cover the surface, they appear to grow from, or give some allusion to, a basket. These articles are also formed in cast-iron, and used as edgings to beds and plots, in plant-stoves and conservatories.

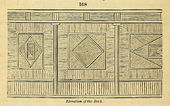

- “1502. The earthenware border (fig. 220.) is composed of long narrow plates of common tile-clay, with the upper edge cut into such shapes as may be deemed ornamental. They form neat and permanent edgings to parterres; and are used more especially in Holland, as casings, or borderings to beds of florists’ flowers. [Fig. 5]

- “1503. Edgings of various sorts are formed of wire, basket-willows, laths, boards, plate-iron, and cast-iron; the last is much the best material."

- Part II, Book III, Chapter II (pp. 303-06, 307-09, 310, 311-12, 314, 315, 322, 323, 328)

- “1555. Fixed structures consist chiefly of erections for the purpose of improving the climate of plants by shelter, by supplying heat, and by exposing them to the influence of the sun. The genera are walls and espalier rails, of each of which the species are numerous.

- “1556. Garden-walls are formed either of brick, wood, stone, or earth, or brick and stone together; and they are either solid, flued, or cellular, upright or sloping, straight or angular.

- “1557. Brick, stone, or mud walls consist of three parts, the foundation, the body of the wall, and the coping. . . .

- “1558. The brick and stone wall is a stone wall faced with four inches of brick-work, or what is called brick and bed, on the side most exposed to the sun, as on the south sides of east and west walls, and on the insides for the sake of appearance of the two end, or north and south walls of enclosed gardens. . . .

- “1559. The solid brick wall is the simplest of all garden-walls, and where the height does not exceed 6 feet, 9 inches in thickness will suffice; when above that to 13 feet, 14 inches, and when from 13 to 20 feet, 18 inches in width are requisite. . . .

- “1560. The flued wall, or hot-wall (figs. 236, & 237.) is generally built entirely of brick, though where stone is abundant and more economical, the back or north side may be of that material. A flued wall may be termed a hollow wall, in which the vacuity is thrown into compartments (a, a, a, a), to facilitate the circulation of smoke and heat, from the base or surface of the ground to within one or two feet of the coping. . . . A wooden or wire trellis is also occasionally placed before flued walls. . . .[Fig. 6]

- “1561. The cellular wall (fig. 238.) is a recent invention (Hort. Trans. vol. iv), the essential part of the construction of which is, that the wall is built hollow, or at least with communicating vacuities, equally distributed from the surface of the ground to the coping. . . . The advantages of this wall are obviously considerable in the saving of material, and in the simple and efficacious mode of heating; but the bricks and mortar must be of the best quality. . . . [Fig. 7]

- “1562. Hollow walls may also be formed by using English instead of Flemish bond: that is, laying one course of bricks along each face of the wall on edge, and then bonding them by a course laid across and flat. . . .

- “1563. Where wall-fruit is an object of consideration, the whole of the walls should be flued or cellular, in order that in any wet or cold autumn, the fruit and wood may be ripened by the application of gentle fires, night and day, in the month of September. . . .

- “1564. The mud or earth-wall (fig. 239.) is formed of clay, or better of brick earth in a state between moist and dry, compactly rammed and pressed together between two moveable boarded sides . . . retained in their position by a frame of timber . . . which form, between them the section of the wall . . . these boarded sides are placed, inclining to each other, so as to form the wall tapering as it ascends. . . .[Fig. 8]

- “1565. Boarded or wooden walls . . . are variously constructed. One general rule is, that the boards of which they are composed, should either be imbricated or close-jointed, in order to prevent a current of air from passing through the seams; and in either case well nailed to the battens behind, in order to prevent warping from the sun. When well tarred and afterwards pitched, such walls may last many years. They must be set on stone posts, or the main parts or supports formed of cast-iron. . . .\

- “1567. The wavy or serpentine wall (fig. 241.) has two avowed objects; first, the saving of bricks, as a wall in which the centres of the segments composing the line are fifteen feet apart, may be safely carried fifteen feet high, and only nine inches in thickness from the foundations; and a four-inch wall may be built seven feet high on the same plan. The next proposed advantage is, shelter from all winds in the direction of the wall; but this advantage seems generally denied by practical men. . . .

- “1568. The angular wall (fig. 242.) is recommended on the same general principles of shelter and economy as above; it has been tried nearly as frequently, and as generally condemned on the same grounds. [Fig. 9]

- “1569. The zig-zag wall . . . is an angular wall in which the angles are all right angles, and the length of their external sides one brick or nine inches. This wall is built on a solid foundation, one foot six inches high, and fourteen inches wide. It is then commenced in zig-zag, and may be carried up to the height of fifteen or sixteen feet of one brick in thickness, and additional height may be given by adding three or four feet of brick on edge. . . .

- “1570. The square fret wall . . . is a four-inch wall like the former, and the ground-plan is formed by joining a series of half-squares, the sides of which are each of the proper length for training one tree during two or three years.

- “1571. The nurseryman’s, or self-supported four-inch wall . . . is formed in lengths of from five to eight feet, and of one brick in breadth, in alternate planes, so that the points of junction form in effect piers nine by four and a half inches. . . .

- “1572. The piered wall . . . may be of any thickness with piers generally of double that thickness, placed at regular distances, and seldom exceeding the wall in height, unless for ornament. . . .[Fig. 10]

- “1575. Trellised walls are sometimes formed when the material of the wall is soft, as in mud walls; rough, as in rubble-stone walls, or when it is desired not to injure the face of neatly finished brick-work. Wooden trellises have been adopted in several places, especially when the walls are flued. . . .

- “1576. Espalier rails are substitutes for walls, and which they so far resemble, that trees are regularly spread and trained along them, are fully exposed to the light, and having their branches fixed are less liable to be injured by high winds. They are formed of wood, cast-iron, or wire and wood.

- “1577. The wooden espalier, of the simplest kind, is merely a straight row of stakes driven in the ground at six or eight inches asunder, and four or five feet high, and joined and kept in a line at top by a rail of wood, or iron hoop, through which one nail is driven into the heart of each stake. . . .

- “1578. The framed wooden espalier rail is composed of frames fitted with vertical bars at six or eight inches asunder, which are nailed on in preference to mortising, in order to preserve entire the strength of the upper and lower rails. . . .

- “1579. The cast-iron espalier rail (fig. 248.) resembles a common street railing, but it is made lighter. . . . [Fig. 11]

- “1580. The horizontal espalier rail (figs.249, &250.) is a frame of wood or iron, of any form or magnitude, and either detached or united, fitted in with bars, and placed horizontally, at any convenient distance from the ground. . . . [Fig. 12]

- “1581. The oblique espalier rail is composed of bars, wires, or lattice-work, placed obliquely.”

- “1582. Of fixed structures, the brick wall, both as a fence, and retainer of heat, may be reckoned essential to every kitchen-garden; and in many cases the mode of building them hollow may be advantageously adopted. . . .

- “1584. Green-houses were known in this country in the seventeenth century. They were then, and continued to be, in all probability, till the beginning of the 18th century, mere chambers distinguished by more glass windows in front than were usual in dwelling-rooms. Such was the green-house in the apothecaries’ garden at Chelsea. . . .

- “1585. The first æra of improvement may be dated 1717, when Switzer published a plan for a forcing-house, suggested by the Duke of Rutland’s graperies at Belvoir Castle. Miller, Bradley, and others, now published designs, in which glass roofs were introduced. . . .

- “1586. A second æra of improvement may be dated from the time when Dr. Anderson published a treatise on his patent hot-house, and from the publication of Knight’s papers in the Horticultural Society’s Transactions, both of which happened about 1809. Not that the scheme of Dr. Anderson ever succeeded, or is at all likely to answer to the extent imagined by its inventor; but the philosophical discussion connected with its description and uses, excited the attention of some gardeners, as did the remarks of Knight on the proper slope of glass roofs (Hort. Trans. vol. i.); and both contributed, there can be no doubt, to produce the patent hot-houses of Stewart and Jorden, and other less known improvements. These, though they may now be considered as reduced au merite historique, yet were really beneficial in their day. Knight’s improvements chiefly respected the angle of the glass roof; a subject first taken up by Boerhaave about a century before, adopted by Linnaeus (Amen. Acad. i. 44.), and subsequently enlarged on by Faccio in 1699, Adanson (Familles des Plantes, tom, i.) in 1763, Miller in 1768, Speechley in 1789, John Williams of New York (Tr. Ag. Soc. New York, 2d edit.) in 1801, Knight in 1806, and by some intermediate authors whom it is needless to name.

- “1587. The last and most important æra is marked by the fortunate discovery of Sir G. Mackenzie in 1815, ‘that the form of glass roofs best calculated for the admission of the sun’s rays is a hemispherical figure.’. . .

- “1591. . . . The object or end of hot-houses is to form habitations for vegetables, and either for such exotic plants as will not grow in the open air of the country where the habitation is to be erected; or for such indigenous or acclimated plants as it is desired to force or excite into a state of vegetation, or accelerate their maturation at extraordinary seasons. The former description are generally denominated green-houses or botanic stoves, in which the object is to imitate the native climate and soil of the plants cultivated; the latter comprehend forcing-houses and culinary stoves, in which the object is, in the first case, to form an exciting climate and soil, on general principles; and in the second, to imitate particular climates. . . .

- “1595. The introduction and management of light is the most important point to attend to in the construction of hot-houses. . . .

- “1602. The general form and appearance of roofs of hot-houses, was, till very lately, that of a glazed shed or lean-to; differing only in the display of lighter or heavier frame-work or sashes. But Sir George Mackenzie’s paper on this subject, and his plan and elevation of a semi-dome (Hort. Trans. vol. ii. p. 175.), have materially altered the opinion of scientific gardeners. . . .

- “1603. Some forms of hot-houses on the curvilinear principle shall now be submitted, and afterwards some specimens of the forms in common use; for common forms, it is to be observed, are not recommended to be laid aside in cases where ordinary objects are to be attained in the easiest manner; and they are, besides the forms of roofs, the most convenient for pits, frames, and glass tents, as already exemplified in treating of these structures. . . .

- “1640. Walls of some sort are necessary for almost every description of hot-house, for even those which are formed of glass on all sides are generally placed on a basis of masonry. But as by far the greater number are erected for culinary purposes, they are placed in the kitchen-garden, with the upper part of their roof leaning against a wall, which forms their northern side or boundary, and is commonly called the back wall, and the lower part resting on a low range of supports of iron or masonry, commonly called the front wall. . . .

- “1647. The most general mode of heating hot-houses is by fires and smoke-flues, and on a small scale, this will probably long remain so. Heat is the same material, however produced; and a given quantity of fuel will produce no more heat when burning under a boiler than when burning in a common furnace. Hence, with good air-tight flues, formed of well burnt bricks and tiles accurately cemented with lime-putty, and arranged so as the smoke and hot air may circulate freely, every thing in culture, as far as respects heat, may be perfectly accomplished. . . .

- “1671. Trellises are of the greatest use in forcing-houses and houses for fruiting the trees of hot climates. On these the branches are readily spread out to the sun, of whose influence every branch, and every twig and single leaf partake alike, whereas, were they left to grow as standards, unless the house were glass on all sides, only the extremities of the shoots would enjoy sufficient light. The advantages in point of air, water, pruning, and other parts of culture, are equally in favor of trellises, independently altogether of the tendency which proper training has on woody fruit-trees, to induce fruitfulness.

- “1672. The material of the trellis is either wood or metal; its situation in culinary hot-houses is against the back wall, close under the glass roof, or in the middle part of the house, or in all these modes. . . .

- “1674. The middle trellis. . . .

- “1675. The front or roof trellis. . . .

- “1676. The fixed rafter-trellis. . . .[Fig. 13]

- “1677. The moveable rafter-trellis. . . .

- “1678. The secondary trellis. . . .

- “1679. The cross trellis.”

- Part II, Book III, Chapter III (pp. 337, 339, 340, 341-342, 347, 348, 350, 351, 352, 354–55, 355-57, 358-59, 360, 361)

- “1712. Entrance lodges and gates more properly belong to architecture than gardening. But, as in small places, they are sometimes designed by the garden-architect, or landscape-gardener, a few remarks may be of use. . . . A handsome architectural entrance is but a poor compensation for its want of harmony with the mansion. . . .

- “1719. Ponds or large basins (fig. 286) are reservoirs formed in excavations, either in soils retentive of water, or rendered so by the use of clay. . . . Sometimes these basins are lined with pavement, tiles, or even lead, and the last material is the best, where complete dryness is an object around the margin. . . .[Fig. 14]

- “1722. Collecting and preserving ice, rearing bees, &c. however, unsuitable or discordant it may appear, it has long been the custom to delegate to the care of the gardener. In some cases also he has the care of the dove-house, fish-ponds, aviary, a menagerie of wild beasts, and places for snails, frogs, dormice, rabbits, &c. but we shall only consider the ice-house, apiary, and aviary, as legitimately belonging to gardening, leaving the others to the care of the gamekeeper, or to constitute a particular department in domestic or rural economy. . . .

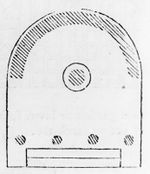

- “1725. The form of ice-houses commonly adopted at country-seats, both in Britain and in France, is generally that of an inverted cone, or rather hen’s egg, with the broad end uppermost. . . .[Fig. 15]

- “1733. The care of bees seems more naturally to belong to gardening than the keeping of ice; because their situation is naturally in the garden, and their produce is a vegetable salt. The garden-bee is found in a wild state in most parts of the globe, in swarms or governments; but never in groups of governments so near together as in a bee-house, which is an artificial and unnatural contrivance to save trouble, and injurious to the insect directly as the number placed together. . . . Hence, independently of other considerations, one disadvantage of congregating hives in bee-houses or apiaries. The advantages are, greater facility in protecting from heats, colds, or thieves, and greater facilities of examining their condition and progress. Independently of their honey, bees are considered as useful in gardens, by aiding in the impregnation of flowers. For this purpose, a hive is sometimes placed in a cherry-house, and sometimes in peach-houses; or the position of the hive is in the front or end wall of such houses, so as the body of the hive may be half in the house and half in the wall, with two outlets for the bees, one into the house, and the other into the open air. By this arrangement, the bees can be admitted to the house and open air alternately, and excluded from either at pleasure.

- “1734. The apiary, or bee-house. The simplest form of a bee-house consists of a few shelves in a recess of a wall or other building . . . exposed to the south, and with or without shutters, to exclude the sun in summer, and, in part, the frost in winter. The scientific or experimental bee-house is a detached building of boards, differing from the former in having doors behind, which may be opened at any time during day to inspect the hives. . . . Bee-houses may always be rendered agreeable, and often ornamental objects: they are particularly suitable for flower-gardens; and one may occur in a recess in a wood or copse, accompanied by a picturesque cottage and flower-garden. They enliven a kitchen-garden, and communicate particular impressions of industry and usefulness. . . .

- “1761. The canary or singing-bird aviary used not unfrequently to be formed in the opaque-roofed green-house or conservatory, by enclosing one or both ends with a partition of wire; and furnishing them with dead or living trees, or spray and branches suspended from the roof for the birds to perch on. Such are chiefly used for the canary, bullfinch, linnet, &c.

- “1762. The parrot aviary is generally a building formed on purpose, with a glass roof, front, and ends; with shades and curtains to protect it from the sun and frost, and a flue for winter heating. In these, artificial or dead trees with glazed foliage are fixed in the floor, and sometimes cages hung on them; and at other times the birds allowed to fly loose. . . .

- “1763. The verdant aviary is that in which, in addition to houses for the different sorts of birds, a net or wire curtain is thrown over the tops of trees, and supported by light posts or hollow rods, so as to enclose a few poles, or even acres of ground, and water in various forms. In this the birds in fine weather sing on the trees, the aquatic birds sail on the water, or the gold-pheasants stroll over the lawn, and in severe seasons they betake themselves to their respective houses or cages. Such an enclosed space will of course contain evergreen, as well as deciduous trees, rocks, reeds, aquatics, long grass for larks and partridges, spruce firs for pheasants, furzebushes for linnets, &c. . . .

- “1764. Gallinaceous aviary. At Chiswick, portable netted enclosures, from ten to twenty feet square, are distributed over a part of the lawn, and display a curious collection of domestic fowls. In each enclosure is a small wooden box or house for sheltering the animals during the night, or in severe weather, and for breeding. Each cage or enclosure is contrived to contain one or more trees or shrubs; and water and food are supplied in small basins and appropriate vessels. Curious varieties of aquatic fowls might be placed on floating aviaries on a lake or pond. . . .

- “1769. Useful decorations are such as while they serve as ornaments, or to heighten the effect of a scene, are also applied to some real use, as in the case of cottages and bridges. They are the class of decorative buildings most general and least liable to objection. . . .

- “1782. The bridge is one of the grandest decorations of garden-scenery, where really useful. None require so little architectural elaboration, because every mind recognises the object in view, and most minds are pleased with the means employed to attain that object in proportion to their simplicity. There are an immense variety of bridges, which may be classed according to the mechanical principles of their structure; the style of architecture, or the materials used. . . .

- “1783. The fallen tree is the original form, and may sometimes be admitted in garden-scenery, with such additions as will render it safe, and somewhat commodious.

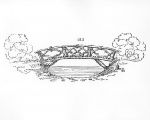

- “1784. The foot-plank is the next form, and may or may not be supported in the middle, or at different distances by posts.

- “1785. The Swiss bridge (figs'. 312, 313.) is a rude composition of trees unbarked, and not hewn or polished. . . . [Figs. 16 and 17]

- “1787. A very light and strong bridge may be formed by screwing together thin boards in the form of a segment, or by screwing together a system of triangles of timber. . . .

- “1788. Bridges of common carpentry . . . admit of every variety of form, and either of rustic workmanship or with unpolished materials, or of polished timber alone, or of dressed timber and abutments of masonry.

- “1789. Bridges of masonry . . . may either have raised or flat roads; but in all cases those are the most beautiful (because most consistent with utility) in which the road on the arch rises as little above the level of the road on the shores as possible. . . .

- “1790. Cast-iron bridges are necessarily curved; but that curvature, and the lines which enter into the architecture of their rails, may be varied according to taste or local indications. . . .

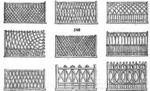

- “1794. The gate is of various forms and materials, according to those of the barrier of which it constitutes a part. In all gates, the essential part of the construction, or those lines which maintain its strength and position, and facilitate its motion, are to be distinguished from such (a, a, fig. 319; fig. 320.) as serve chiefly to render it a barrier, or as decorations. Thus a gate with a raised top or head (fig. 321.) is almost always in bad taste, because at variance with strength; while the contrary form (fig. 320.) is generally in good taste, for the contrary reason. In regard to strength, the nearer the arrangement of rails and bars approaches in effect to one solid lamina, or plate of wood or iron, of the gate’s dimensions, the greater will be the force required to tear or break it in pieces. But this would not be consistent with lightness and economy, and, therefore, the skeleton of a lamina is resorted to, by the employment of slips or rails joined together on mechanical principles; that is, on principles derived from a mechanical analysis of strong bodies. . . . [Fig. 18]

- “1800. Gates, as decorations, may be classed according to the prevailing lines, and the materials used. Horizontal, perpendicular, diagonal, and curved lines, comprehend all gates, whether of iron or of timber, and each of these may be distinguished more or less by ornamental parts, which may either be taken from any of the known styles of architecture, or from heraldry or fancy.

- “1801. The published designs for gates are numerous, especially those for iron gates; for executing which, the improvements made in casting that metal in moulds afford great facilities. By a judicious junction of cast and wrought iron, the ancient mode of enriching gates with flowers and other carved-like ornaments might be happily reintroduced.

- “1802. Gates in garden-scenery, where architectural elegance is not required to support character, simple or rustic structures (fig. 326.), wickets, turn-stiles, and even moveable or suspended rails, like the German schlagbaum . . . may be introduced according to the character of the scene. . . .[Fig. 19]

- “1804. Walls are unquestionably the grandest fences for parks; and arched portals, the noblest entrances; between these and the hedge or pale, and rustic gate, designs in every degree of gradation, both for lodges, gates, and fences, will be found in the works of Wright, Gandy, Robertson, Aikin, Pocock, and other architects who have published on the rural department of their art. The pattern books of manufacturers of iron gates and hurdles, and of wire workers, may also be advantageously consulted. . . .

- “1805. Of convenient decorations the variety is almost endless, from the prospect-tower to the rustic seat; besides aquatic decorations, agreeable to the eye and convenient for the purposes of recreations or culture. Their emplacement, as in the former section, belongs to gardening, and their construction to architecture and engineering. . . .

- “1808. Temples, either models or imitations of the religious buildings of the Greeks and heathen Romans, are sometimes introduced in garden-scenery to give dignity and beauty. In residences of a certain extent and character, they may be admissible as imitations, as resting-places, and as repositories of sculptures or antiquities. Though their introduction had been brought into contempt by its frequency, and by bad imitations in perishable materials, yet they are not for that reason to be rejected by good taste. They may often add dignity and a classic air to a scene; and when erected of durable materials, and copied from good models, will, like their originals, please as independent objects. . . .

- “1809. Porches and porticoes (fig. 330.) are sometimes employed as decorative marks to the entrances of scenes; and sometimes merely as roofs to shelter seats or resting benches.” [Fig. 20]

- "1810. Alcoves (fig. 331.) are used as winter resting places, as being fully exposed to the sun. . . .[Fig. 21]

- “1811. Arbors are used as summer seats and resting-places: they may be shaded with fruit-trees, as the vine, currant, cherry; climbing ornamental shrubs, as ivy, clematis, &c.; or herbaceous, as everlasting pea, gourd, &c. They are generally formed of timber lattice-work, sometimes of woven rods, or wicker-work, and occasionally of wire.

- “1812. The Italian arbor (fig. 332.) is generally covered with a dome, often framed of thick iron or copper wire painted, and covered with vines or honeysuckles.

- “1813. The French arbor (fig. 333.) is characterised by the various lines and surfaces, which enter into the composition of the roof. . . .[Fig. 22]

- “1815. Grottoes are resting-places in recluse situations, rudely covered externally, and within finished with shells, corals, spars, crystallisations, and other marine and mineral productions, according to fancy. To add to the effect, pieces of looking-glass are inserted in different places and positions.

- “1816. Roofed seats, boat-houses, moss houses, flint houses, bark huts, and similar constructions, are different modes of forming resting-places containing seats, and sometimes other furniture or conveniences in or near them. . . .[Fig. 23]

- “1817. Roofed seats of a more polished description are boarded structures generally semi-octagonal, and placed so as to be open to the south. Sometimes they are portable, moving on wheels, so as to be placed in different positions, according to the hour of the day, or season of the year, which, in confined spots, is a desirable circumstance. Sometimes they turn on rollers, or on a central pivot, for the same object, and this is very common in what are called barrel-seats. In general they are opaque, but occasionally their sides are glazed, to admit the sun to the interior in winter.

- “1818. Folding chairs. A sort of medium seat, between the roofed and the exposed, is formed by constructing the backs of chairs, benches, or sofas with hinges, so as they may fold down over the seat, and so protect it from rain. . . .

- “1819. Elegant structures of the seat kind for summer use, may be constructed of iron rods and wires, and painted canvas; the iron forming the supporting skeleton, and the canvass the protecting tegument. . . .[Fig. 24]

- “1820. Exposed seats include a great variety, rising in gradation from the turf bank to the carved couch. Intermediate forms are stone benches, root stools, sections of trunks of trees, wooden, stone, or cast-iron mushrooms painted or covered with moss, or mat, or heath; the Chinese barrel-seat, the rustic stool, chair, tripod, sofa, the cast-iron couch or sofa, the wheeling-chair, and many sub-varieties. . . .

- “1822. Of constructions for displaying water, as an artificial decoration, the principal are cascades, waterfalls, jets, and fountains. . . .

- “1826. The construction of the waterfall, where avowedly artificial, is nothing more than a strong-built wall across the stream, perfectly level at top, and with a strong, smooth, accurately fitted, and well jointed coping. . . . Where a natural waterfall is to be imitated, the upright wall must be built of huge irregular blocks; the horizontal lamina of water broken in the same way by placing fragments of rocks grouped here and there so as to throw the whole into parts; and as nature is never methodical, to form it as if in part a cascade. . . .

- “1827. In imitating a natural cascade in garden-scenery, the horizontal line must here also be perfect, to prevent waste of water in dry seasons, and from this to the base of the lower slope the surface must be paved by irregular blocks, observing to group the prominent fragments, and not distribute them regularly over the surface. . . .

- “1828. The greatest danger in imitating cascades and waterfalls, consisting in attempting too much, a very few blocks, disposed with a painter’s eye, will effect all that can be in good taste in most garden-scenes; and in forming or improving them in natural rivers, there will generally be found indications both as to situation and style, especially if the country be uneven, or stony, or rocky. . . .

- “1829. Jets and other hydraulic devices, though now in less repute than formerly, are not to be rejected in confined artificial scenes, and form an essential decoration where the ancient style of landscape is introduced in any degree of perfection.

- “1830. The first requisite for jets or projected spouts, or threads of water, by atmospheric pressure, is a sufficiently elevated source or reservoir of supply. This being obtained, pipes are to be conducted from it to the situations for the jets. . . .

- “1831. Adjutages are of various sorts. Some are contrived so as to throw up the water in the form of sheaves, fans, showers, to support balls, &c.; others to throw it out horizontally, or in curved lines, according to the taste of the designer; but the most usual form is a simple opening to throw the spout or jet upright. The grandest jet of any is a perpendicular column issuing from a rocky base, on which the water falling, produces a double effect both of sound and visual display. A jet rising from a naked tube in the middle of a basin or canal, and the waters falling on its smooth surface, is unnatural, without being artificially grand.

- “1832. Drooping fountains (figs. 341, 342, 343.), overflowing vases, shells (as the chama gigas), cisterns, sarcophagi, dripping rocks, and rockworks, are easily formed, requiring only the reservoir to be as high as the orifice whence the dip or descent proceeds. This description of fountains, with a surrounding basin, are peculiarly adapted for the growth of aquatic plants. . . .[Fig. 25]

- “1834. Sun-dials are venerable and pleasing garden-decorations; and should be placed in conspicuous frequented parts, as in the intersection of principal walks, where the ‘note which they give of time’ may be readily recognised by the passenger. Elegant and cheap forms are now to be procured in cast-iron, which, it is to be hoped, will render their use more frequent. . . .

- “1838. Rockworks for effect or character require more consideration than most gardeners are aware of. The first thing is to study the character of the country, and of the strata of earthy materials, whether earth, gravel, sand, or rock, or a mere nucleus of either of these, such as they actually exist, so as to decide whether rocks may, with propriety, be introduced at all; or, if to be introduced, of what kind, and to what extent. The design being thus finally fixed on, the execution is more a matter of labor than of skill. . . .

- “1842. Monumental objects, as obelisks, columns, pyramids, may occasionally be introduced with grand effect, both in a picturesque and historical view, of which Blenheim, Stow, Castle Howard, &c., afford fine examples; but their introduction is easily carried to the extreme, and then it defeats itself, as at Stow. . . .

- “1843. Sculptures. Of statues, therms, busts, pedestals, altars, urns, and similar sculptures, nearly the same remark may be made. Used sparingly, they excite interest, often produce character, and are always individually beautiful, as in the pleasure-grounds of Blenheim, where a few are judiciously introduced; but profusely scattered about, they distract attention."

- Part II, Book IV, Chapter II (pp. 375, 377)

- “1924. Intricate and fanciful figures of parterres are most correctly transferred to ground, as they are copied on paper, by covering the figure to be copied with squares (fig. 363. a) formed by temporary lines intersecting each other at equal distances and right angles, and by tracing on the ground similar squares, but much larger, according to the scale (fig. 363. b). Sometimes the figure is drawn on paper in black, and the squares in red, while the squares on the ground are formed as sawyers mark the intended path of the saw before sawing up a log of timber; that is, by stretching cords rubbed with chalk, which, by being struck on the ground (previously made perfectly smooth), leave white lines. With the plan in one hand and a pointed rod in the other, the design is thus readily traced across these indications. The French and Italians lay out their most curious parterres . . . in this way. . . .[Fig. 26]

- “1933. Levelling for terrace-slopes (fig. 369.), or for geometrical surfaces, however varied, is performed by the union of both modes, and requires no explanation to those who have acquired the rudiments of geometry, or understand what has been described." [Fig. 27]

- Part II, Book IV, Chapter IV (p. 451)

- “2355. To unite the agreeable with the useful is an object common to all the departments of gardening. The kitchen garden, the orchard, the nursery, and the forest, are all intended as scenes of recreation and visual enjoyment, as well as of useful culture; and enjoyment is the avowed object of the flower-garden, shrubbery, and pleasure ground."

- Part III, Book I, Chapter I (pp. 455, 456, 457-58, 464, 465)

- “2382. The situation of the kitchen-garden, considered artificially or relatively to the other parts of a residence, should be as near the mansion and the stable-offices, as is consistent with beauty, convenience, and other arrangements. Nicol observes, ‘In a great place, the kitchen-garden should be so situated as to be convenient, and, at the same time, be concealed from the house. . . .’

- “2383. Sometimes we find the kitchen-garden placed immediately in front of the house, which Nicol ‘considers the most awkward situation of any. . . . Generally speaking, it should be placed in the rear or flank of the house, by which means the lawn may not be broken and rendered unshapely where it is required to be most complete. The necessary traffic with this garden, if placed in front, is always offensive. . . .’

- “2388. Main entrance to the garden. Whatever be the situation of a kitchen-garden, whether in reference to the mansion or the variations of the surface, it is an important object to have the main entrance on the south side, and next to that, on the east or west. The object of this is to produce a favorable first impression on the spectator, by his viewing the highest and best wall (that on the north side) in front; and which is of still greater consequence, all the hot-houses, pits, and frames in that direction. . . .

- “2389. Bird’s-eye view of the garden. When the grounds of a residence are much varied, the general view of the kitchen-garden will unavoidably be looked down on or up to from some of the walks or drives, or from open glades in the lawn or park. Some arrangement will therefore be requisite to place the garden, or so to dispose of plantations that only favorable views can be obtained of its area. To get a bird’s-eye view of it from the north, or from a point in a line with the north wall, will have as bad an effect as the view of its north elevation, in which all its ‘baser parts’ are rendered conspicuous. . . .

- “2396. The extent of the kitchen-garden must be regulated by that of the place, of the family, and of their style of living. In general, it may be observed, that few country-seats have less than an acre, or more than twelve acres in regular cultivation as kitchen-garden, exclusive of the orchard and flower-garden. From one and a half to five acres may be considered as the common quantities enclosed by walls. . . .

- “2401. The kitchen-garden should be sheltered by plantations; but should by no means be shaded, or be crowded by them. If walled round, it should be open and free on all sides, or at least to the south-east and west, that the walls may be clothed with fruit-trees on both sides. . . .

- “2431. In regard to form, almost all the authors above quoted [London, Wise, Evelyn, Hitt, Lawrence] agree in recommending a square . . . or oblong, as the most convenient for a [kitchen] garden; but Abercrombie proposes a long octagon, in common language, an oblong with the angles cut off. . . .

- “2436. Walls are built round a garden chiefly for the production of fruits. A kitchen-garden, Nicol observes, considered merely as such, may be as completely fenced and sheltered by hedges as by walls, as indeed they were in former times, and examples of that mode of fencing are still to be met with. But in order to obtain the finer fruits, it becomes necessary to build walls, or to erect pales and railings."

- Part III, Book I, Chapter III (p. 482)

- “2527. An orchard, or separate plantation of the hardier fruit-trees is a common appendage to the kitchen garden, where that department is small, or does not contain an adequate number of fruit-trees to supply the contemplated demand of the family. Sometimes this scene adjoins the garden, and forms a part of the slip; at other times it forms a detached, and, perhaps, distant enclosure, and not unfrequently, in countries where the soil is propitious to fruit-trees, they are distributed in the lawn, or in a scene, or field kept in pasture. Sometimes the same object is effected by mixing fruit-trees in the plantations near the garden and house.”

- Part III, Book II, Chapter I (pp. 789-91, 792-93, 794, 796-797)

- “6075. Floriculture. . . . The culture of flowers was long carried on with that of culinary vegetables, in the borders of the kitchen-garden, or in parterres or groups of beds, which commonly connected the culinary compartments with the house. In places of moderate extent, this mixed style is still continued; but in residences which aim at any degree of distinction, the space within the walled garden is confined to the production of objects of domestic utility, while the culture of plants of ornament is displayed in the flower-garden and the shrubbery. These, under the general term of pleasure-ground, encircle the house in small seats, and on a larger scale embrace it in one or more sides; the remaining part being under the character of park-scenery. . . .

- “6076. The situation of the flower-garden, as of every department of floriculture, should be near the house, for ready access at all times, and especially during winter and spring, when the beauties of this scene are felt with peculiar force. . . .

- “6079. To place the flower-garden south-east or south-west of the house, and between it and the kitchen-garden, is in general a desirable circumstance. . . .

- “6080. In exposure and aspect, the flower-garden should be laid out as much as possible on the same principles as the kitchen-garden. . . .

- “6081. The extent of the flower-garden depends jointly on the general scale of the residence, and the particular taste of the owner. If any proportion may be mentioned, perhaps, a fifth part of the contents of the kitchen-garden will come near the general average; but there is no impropriety in having a large flower-garden to a small kitchen-garden. . . . As moderation, however, is generally found best in the end, we concur with the author of the Florist’s Manual, when she states, that ‘. . . If the form of ground, where a parterre is to be situated, is sloping, the size should be larger than when a flat surface, and the borders of various shapes, and on a bolder scale, and intermingled with grass; but such a flower-garden partakes more of the nature of pleasure-ground than of the common parterre, and will admit of a judicious introduction of flowering shrubs.’ . . .

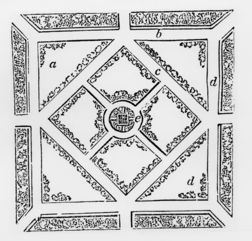

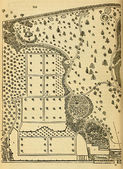

- “6082. Shelter is equally requisite for the flower as for the kitchen garden, and, where naturally wanting, is to be produced by the same means, viz. planting. . . . Sometimes an evergreen hedge will produce all the shelter requisite, as in small gardens composed of earth and gravel only . . . but where the scene is large (fig. 540), and composed of dug compartments (a), placed on lawn (b) the whole may be surrounded by an irregular border (c) of flowers, shrubbery, and trees. . . . [Fig. 28]

- “6086. Water. This material, in some form or other, is as essential to the flower as to the kitchen-garden. Besides the use of the element in common culture, a pond or basin affords an opportunity of growing some of the more showy aquatics, while jets, dropping-fountains, and other forms of displaying water, serve to decorate and give interest to the scene. . . .

- “6087. The form of a small garden . . . will be found most pleasing when some regular figure is adopted, as a circle, oval, octagon, crescent, &c.: but where the extent is so great as not readily to be caught by a single glance of the eye, an irregular shape is generally more convenient, and it may be thrown into agreeable figures, or component scenes, by the introduction of shrubs so as to subdivide the space. . . .

- “6090. Boundary fence, or screen. Parterres on a small scale may be enclosed by an evergreen hedge of holly, box, laurel, privet, juniper, laurustinus, or Irish whin . . . but irregular figures, especially if of some extent, can only be surrounded by a shrubbery, such as we have already hinted at (6082.) as forming a proper shelter for flower-gardens. . . .

- “6092. Rustic fences formed of shoots of the oak, hazel, or larch, may often be introduced with good effect both as interior and surrounding barriers. (fig. 542.) [Fig. 29]

- “6093. Laying out the area. . . . In laying out the area of the kitchen-garden, its destination being utility, affords in all cases a safe and fixed guide; but the flower-garden is a matter of fancy and taste, and where these are wavering and unsettled, the work will be found to go on at random. As flower-gardens are objects of pleasure, that principle which must serve as a guide in laying them out, must be taste. Now, in flower-gardens, as in other objects, there are different kinds of tastes; these embodied are called styles or characters; and the great art of the designer is, having fixed on a style, to follow it out unmixed with other styles, or with any deviation which would interfere with the kind of taste or impression which that style is calculated to produce. Style, therefore, is the leading principle in laying out flower-gardens, as utility is in laying out the culinary-garden. As subjects of fancy and taste, the styles of flower-gardens are various. The modern style is a collection of irregular groups and masses, placed about the house as a medium, uniting it with the open lawn. The ancient geometric style, in place of irregular groups, employed symmetrical forms; in France, adding statues and fountains; in Holland, cut trees and grassy slopes; and in Italy, stone walls, walled terraces, and flights of steps. In some situations, these characteristics of parterres may with propriety be added to, or used instead of the modern sort, especially in flat situations, such as are enclosed by high walls in towns, or where the principal building or object is in a style of architecture which will not render these appendages incongruous. There are other characters of gardens, such as Chinese, which are not widely different from the modern; the Indian, which consists chiefly of walks under shade, in squares of grass, &c.; the Turkish, which abounds in shady retreats, boudoirs of roses and aromatic herbs; and the Spanish, which is distinguished by trellis-work and fountains: but these gardens are not generally adapted to this climate, though from contemplating and selecting what is beautiful or suitable in each, a style of decoration for the immediate vicinity of mansions might be composed, greatly preferable to any thing now in use. . . .

- “6097. The materials which form the surface of flower-gardens (figs. 543, 544.) are gravel (a), turf (b), and dug borders, (c), patches (d), or compartments (e), and water (f); but a variety of other objects and materials may be introduced as receptacles for plants, or on the surfaces of walks; as grotesque roots, rocks, flints, spar, shells, scoriae in conglomerated lumps, sand and gravel of different colors; besides works of art introduced as decorations, or tonsile performances, when the old French style (fig. 545.) is imitated.” [Figs. 30 and 31]

- “6099. The green-house or conservatory is generally placed in the flower-garden, provided these structures are not appended to the house. . . .

- “6105. Walks. In most styles of parterres these are formed of gravel; but in the modern sort (fig. 549), which consist of turf, varied by wavy dug beds (1 and 2), and surrounded by shrubbery. . . . [Fig. 32]

- “6106. In extensive and irregular parterres, one gravel-walk, accompanied by broad margins of turf, to serve as walks by such as prefer that material, should be so contrived as to form a tour for the display of the whole garden. There should also be other secondary interesting walks of the same width, of gravel and smaller walks for displaying particular details. The main walk, however, ought to be easily distinguishable from the others by its broad margins of fine turf. In general the gravel is of uniform breadth throughout the whole length of the walk; but in that sort of French parterres which they call parterres of embroidery (fig. 550.), the breadth of the gravelled part (a) varies like that of the turf. Such figures, when correctly executed, carefully planted, judiciously intermixed with basket-work, shells, party-colored gravels, &c. and kept in perfect order, are highly ornamental; but very few gardeners enter into the spirit of this department of their art. The French and Dutch have long greatly excelled us in the formation of small gardens, and the display of flowers; and whoever wishes to succeed in this department ought to visit Amsterdam, Antwerp, Brussels, and Paris; and consult the old French works of Mallet, Boyceau, Le Blond, &c. [Fig. 33]

- “6107. Edgings. In parterres where turf is not used as a ground or basis out of which to cut the beds and walks, the gravel of the latter is disparted from the dug ground of the former by edgings or rows of low-growing plants, as in the kitchen-garden. Various plants have been used for this purpose; but, as Neill observes, the best for extensive use is the dwarfish Dutch box, kept low and free from blanks. Abercrombie says, ‘Thrift is the neatest small evergreen next to box. In other parts, the daisy, pink, London-pride, primrose, violet, and periwinkle, may be employed as edgings. The strawberry, with the runners cut in close during summer, will also have a good effect; the wood-strawberry is suitable under the spreading shade of trees. Lastly, the limits between the gravel-walks and the dug-work may sometimes be marked by running verges of grass kept close and neat. Whatever edgings are employed, they should be formed previous to laying the gravel.’

- “6108. Basket-edgings. Small groups near the eye, and whether on grass or gravel, may be very neatly enclosed by a worked fence of basket-willows from six inches to a foot high. These wicker-work frames may be used with or without verdant edgings; they give a finished and enriched appearance to highly polished scenery; enhance the value of what is within, and help to keep off small dogs, children, &c."

- Part III, Book II, Chapter II (pp. 797-98, 800-01)

- “6110. The manner of planting the herbaceous plants and shrubs in a flower-garden depends jointly on the style and extent of the scene. With a view to planting, they may be divided into three classes, which classes are independently altogether of the style in which they are laid out. The first class is the general or mingled flower-garden, in which is displayed a mixture of flowers with or without flowering-shrubs according to its size. The object in this class is to mix the plants, as that every part of the garden may present a gay assemblage of flowers of different colors during the whole season. The second class is the select flower-garden, in which the object is limited to the cultivation of particular kinds of plants; as, florists’ flowers, American plants, annuals, bulbs, &c. Sometimes two or more classes are included in one garden, as bulbs and annuals; but, in general, the best effect is produced by limiting the object to one class only. The third class is the changeable flower garden, in which all the plants are kept in pots, and reared in a flower-nursery or reserve-ground. As soon as they begin to flower, they are plunged in the borders of the flower-garden, and, whenever they show symptoms of decay, removed, to be replaced by others from the same source. This is obviously the most complete mode of any for a display of flowers, as the beauties of both the general and particular gardens may be combined without presenting blanks, or losing the fine effect of assemblages of varieties of the same species; as of hyacinth, pink, dahlia, chrysanthemum, &c. The fourth class is the botanic flower-garden, in which the plants are arranged with reference to botanical study, or at least not in any way that has for its main object a rich display of blossoms. . . .

- “6126. The botanic flower-garden being intended to display something of the extent and variety of the vegetable kingdom, as well as its resemblances and differences, should obviously be arranged according to some system or method of study. In modern times, the choice is almost limited to the artificial system of Linnaeus, and the natural method of Jussieu, though Adanson has given above fifty-six different methods by which plants may be arranged. . . . Whatever method is adopted, the plants may either be placed in regular rows, or each order may be grouped apart, and surrounded by turf or gravel. For a private botanic garden, the mode of grouping on turf is much the most elegant. . . .A gravel walk may be so contrived as to form a tour of all the groups [of species] (fig. 553.), displaying them on both sides; in the centre, or in any fitting part of the scene, the botanic hot-houses may be placed; and the whole might be surrounded with a sloping phalanx of evergreen plants, shrubs, and trees. . . . It is hardly necessary to observe that the above modes, or others that we have mentioned of planting a flower-garden are alike applicable to every form or style of laying out the garden or parterre. . . . [Fig. 34]

- “6127. Decorations. Even the apiary and aviary, or, at least, here and there a beehive, or a cage suspended from a tree, will form very appropriate ornaments.”

- Part III, Book II, Chapter III (pp. 802–3)

- “6130. By a shrubbery, or shrub-garden, we understand a scene for the display of shrubs valued for their beauty or fragrance, combining such trees as are considered chiefly ornamental, and some herbaceous flowers. The form or plan of the modern shrubbery is generally a winding border, or strip of irregular width, accompanied by a walk, near to which it commences with the herbaceous plants and lowest shrubs, and as it falls back, the shrubs rise in gradation and terminate in the ornamental trees, also similarly graduated. Sometimes a border of shrubbery accompanies the walk on both sides; at other times only one side, while the other side is, in some cases, a border for culinary vegetables surrounding the kitchen-garden, but most generally it is an accompanying breadth of turf, varied by occasional groups of trees and plants, or decorations, and with the border, forms what is called pleasure-ground.

- “6131. The sort of shrubbery formed under the geometric style of gardening . . . was more compact; it was called a bosque, thicket or wood, and contained various compartments of turf or gravel branching from the walks, and very generally a labyrinth. The species of shrubs in those times being very limited, the object was more walks for recreation, shelter, shade, and verdure, than a display of flowering shrubs. . . .

- “6132. In respect to situation, it is essential that the shrubbery should commence either immediately at the house, or be joined to it by the flower-garden; a secondary requisite is, that however far, or in whatever direction it be continued, the walk be so contrived as to prevent the necessity of going to and returning from the principal points to which it leads over the same ground."

- Part III, Book II, Chapter IV (pp. 804, 806, 807, 809, 810)

- “6138. On planting the shrubbery the same general remarks, submitted as introductory to planting the flower-garden, are applicable; and shrubs may be arranged in as many different manners as flowers. Trees, however, are permanent and conspicuous objects, and consequently produce an effect during winter, when the greater number of herbaceous plants are scarcely visible. This is more especially the case with that class called evergreens, which, according as they are employed or omitted, produce the greatest difference in the winter aspect of the shrubbery. We shall here describe four leading modes for the arrangement of the shrubbery, distinguishing them by the names of the mingled or common, the select or grouped manner, and the systematic or methodical style of planting. Before proceeding farther it is requisite to observe, that the proportion of evergreen trees to deciduous trees in cultivation in this country, is as 1 to 12; of evergreen shrubs to deciduous shrubs, exclusive of climbers and creepers but including roses, as 4 to 8; that the time of the flowering of trees and shrubs is from March to August inclusive, and that the colors of the flowers are the same as in herbaceous plants. These data will serve as guides for the selection of species and varieties for the different modes of arrangement, but more especially for the mingled manner. . . .

- “6141. The select or grouped manner of planting a shrubbery (fig. 559.) is analogous to the select manner of planting a flower-garden. Here one genus, species, or even variety, is planted by itself in considerable numbers, so as to produce a powerful effect. Thus the pine tribe, as trees, may be alone planted in one part of the shrubbery, and the holly, in its numerous varieties, as shrubs. After an extent of several yards, or hundreds of yards, have been occupied with these two genera, a third and fourth, say the evergreen fir tribe and the yew, may succeed, being gradually blended with them, and so on. A similar grouping is observed in the herbaceous plants inserted in the front of the plantation; and the arrangement of the whole as to height, is the same as in the mingled shrubbery. . . .[Fig. 35]

- “6144. Systematic or methodical planting in shrubberies consists, as in flower-planting, in adopting the Linnaean or Jussieuean arrangement as a foundation, and combining at the same time a due attention to gradation of heights. . . . But much the most interesting mode of arrangement would be that of Jussieu, by which a small villa of two or three acres might be raised, as far as gardening is concerned, to the ne plus ultra of interest and beauty. To aid in the formation of such scenes the tables . . . exhibiting the genera contained in each Linnaean or Jussieuean order, and also the number of species distributed according to their places in the garden, will be found of the greatest use. . . .[Fig. 36]

- “6156. Decorations in shrubberies. Those of the shrubbery should in general be of a more useful and imposing character than such as are adopted in the flower-garden. The green-house and aviary are sometimes introduced, but not, as we think, with propriety, owing to the unsuitableness of the scene for the requisite culture and attention. Open and covered seats are necessary, or, at least, useful decorations, and may occur here and there in the course of the walk, in various styles of decoration, from the rough bench to the rustic hut (fig. 561) and Grecian temple (fig. 562) Great care, however, must be taken not to crowd these nor any other species of decorations. Buildings being more conspicuous than either statues urns, or inscriptions, require to be introduced more sparingly, and with greater caution. In garden or ornamented scenery they should seldom obtrude themselves by their magnitude or glaring color; and rarely be erected but for some obvious purpose of utility. [Figs. 37 and 38]

- “6157. . . . Light bowers formed of lattice-work, and covered with climbers, are in general most suitable to parterres; plain covered seats suit the general walks of the shrubbery. . . .

- “6158. Statues, whether of classical or geographical interest (figs. 564. and 565.), urns, inscriptions, busts, monuments, &c. are materials which should be introduced with caution. None of the others require so much taste and judgement to manage them with propriety. The introduction of statues, except among works of the most artificial kind, such as fine architecture, is seldom or never allowable; for when they obtrude themselves among natural beauties, they always disturb the train of ideas which ought to be excited in the mind, and generally counteract the character of the scenery. In the same way, busts, urns, monuments, &c. in flower-gardens, are most generally misplaced. The obvious intention of these appendages is to recall to mind the virtues, qualities, or actions of those for whom they were erected: now this requires time, seclusion, and undisturbed attention, which must either render all the flowers and other decoration of the ornamental garden of no effect; or, if they have effect, it can only be to interrupt the train of ideas excited by the other. As the garden, and the productions of nature, are what are intended to interest the spectator, it is plain that the others should not be introduced.” [Figs. 39 and 40]

- Part III, Book II, Chapter V (pp. 811, 812, 813, 814)

- “6161. The hot-houses of floriculture are the frame, glass case, green-house, orangery, conservatory, dry-stove, the bark or moist stove, in the flower-garden, or pleasure-ground; and the pit and hot-bed in the reserve-garden. In the construction of all of these the great object is, or ought to be, the admission of light and the power of applying artificial heat with the least labor and expense. . . .

- “6164. The green-house may be designed in any form, and placed in almost any situation as far as respects aspect. Even a house looking due north, if glazed on three sides of the roof, will preserve plants in a healthy vigorous state. A detached green-house, even in the old style, may be rendered an agreeable object in a pleasure-ground . . . but the curvilinear principle applied to this class of structures, admits of every combination of form, and without militating against the admission of light and air. Though we are decidedly of opinion, however, that as iron roofs on the curvilinear principle become known, the clumsy shed-like wooden or mixed roofs now in use will be erected only in nursery and market-gardens. . . .[Fig. 41]

- “6165. The most suitable description of greenhouse or conservatory for the flower-garden is that with span roof (fig. 568), because such a house has no visible ‘hinder parts,’ back sheds, stock-holes, or other points of ugliness, with which it is difficult to avoid associating all the shed, or lean-to forms of glazed buildings with back walls. . . .[]

- “6166. In the interior of the green-house the principle object demanding attention is the stage, or platform for the plants. . . .

- “6171. The orangery is the green-house of the last century, the object of which was to preserve large plants of exotic evergreens during winter, such as the orange tribe, myrtles, sweet bays, pomegranates, and a few others. . . . The orangery was generally placed near to or adjoining the house, and its elevation corresponded in architectural design with that of the mansion. From this last circumstance has arisen a prejudice highly unfavorable to the culture of ornamental exotics, namely, that every plant-habitation attached to a mansion should be an architectural object, and consist of windows between stone piers or columns, with a regular cornice and entablature. By this mode of design, these buildings are rendered so gloomy as never to present a vigorous vegetation, and vivid glowing colors within; and as they are thus unfit for the purpose for which they are intended, it does not appear to us, as we have already observed at length (1590.), that they can possibly be in good taste. Perhaps the only way of reconciling the adoption of such apartments with good sense, is to consider them as lounges or promenade scenes for recreation in unfavorable weather, or for use during fêtes, in either of which cases they may be decorated with a few scattered tubs of orange-trees, camellias, or other evergreen coriaceous-leaved plants from a proper green-house, and which will not be much injured by a temporary residence in such places, which, as Nicol has observed, ‘often look more like tombs or places of worship, than compartments for the reception of plants; and, we may add that the more modern sort look like a combination of shop-fronts, of which that at Claremont is a notable example.’ Sometimes structures of this sort are erected to conceal some local deformity, of which, as an instance, we may refer to that (fig. 570) erected by Todd, for J. Elliot, Esq., at Pimlico. ‘This building was constructed for the purpose of preventing the prospect of some offices from the dwelling-house. The architectural ornaments, and the roof, not being of glass, are points in the construction not generally to be recommended; but, as it was built for the purpose above mentioned, the objections were overruled. There are three circular stages to this house, which are made to take out at pleasure. The ceiling forms part of a circle, and the floor is paved with Yorkshire stone. It is fifty feet long, and thirteen feet six inches wide, and heated by one fire, the flue from which makes the circuit of the house under the floor.’ (Plans of Green-Houses, &c. p. 10)”. . . .[Fig. 42]

- “6174. The conservatory is a term generally applied by gardeners to plant-houses, in which the plants are grown in a bed or border without the use of pots. They are sometimes placed in the pleasure-ground along with the other hot-houses; but more frequently attached to the mansion. The principles of their construction is in all respects the same as for the green-house, with the single difference of a pit or bed of earth being substituted for the stage, and a narrow border instead of surrounding flues. The power of admitting abundance of air, both by the sides and roof, is highly requisite both for the green-house and conservatory; but for the latter, it is desirable, in almost every case, that the roof, and even the glazed sides, should be removable in summer.”

- Part III, Book II, Chapter VIII (p. 884)

- “6525. The ground-plan and figure of the elevation of the rock-work must, as in the case of the aquarium, be made to harmonise with surrounding objects. Simple outlines and surfaces, not too much broken, show the plants to most advantage, and are not so liable to ridicule as imitations of hills or mountains, or high narrow cones, or peaks of scoriæ in the Chinese manner, which are to be seen in some places, A ground-plan, in the form of a crescent, or of any wavy figure widest towards the middle part of its length, and with the surface not steeper than forty-five degrees (fig. 619) will be found well suited to the less durable materials, such as bricks, pudding-stone, scoriæ, &c. which are found in flat countries. Sometimes one side of such rock-works may be nearly perpendicular, in which case, if facing the north, it affords an excellent situation for ferns and mosses.” [Fig. 43]

- Part III, Book III, Chapter II (pp. 942–43)

- "6810.Assemblage of trees, whether natural or artifical, differe in extent, outline, disposition of the trees and kind of trees.

- “6811. In regard to extent, the least is a group (fig. 628. e and d), which must consist at least of two plants; larger, it is called a thicket (b c); round and compact, it is called a clump (a); still larger, a mass; and all above a mass is denominated a wood or forest, and characterised by comparative degrees of largeness. The term wood may be applied to a large assemblage of trees, either natural or artificial; forest, exclusively to the most extensive or natural assemblages. . . .[Fig. 44]

- “6813. With respect to the disposition of the trees within the plantation, they may be placed regularly in rows, squares, parallelograms, or quincunx; irregularly in the manner of groups; without undergrowths, as in groves (fig. 629. a, b); with undergrowths, as in woods (c); all undergrowths, as in copse-woods (d). Or they may form avenues (fig. 630. a); double avenues (b); avenues intersecting in the manner of a Greek cross (c); of a martyr’s cross (d); of a star (e) or of a cross patée, or duck’s foot (patée d’oye) (f)." [Figs. 45 and 46]

- Part III, Book III, Chapter IV (pp. 950, 952, 954)

- “6853. The situations [of plantations] to be planted, with a view to effect, necessarily depends on the kind of effect intended; these may reduced to three—to give beauty and variety to general scenery, as in forming plantations here and there throughout a demesne; to give form and character to a country-residence, as in planting a park and pleasure-grounds; and to create a particular and independent beauty or effect, as in planting an extensive area or wood, unconnected with any other object, and disposing of the interior in avenues, glades, and other forms. . . .

- “6855. The outline of plantations, made with a view to the composition of a country-residence, is guided by the same general principles; whether the trees are to be disposed in regular forms, avowedly artificial; or in irregular forms, in imitation of nature. . . . The first thing is, in both modes, to compose a principal mass, from which the rest may appear to proceed; or be, or seem to be, connected. . . .

- “6861. Placing the groups. Another practice in the employment of groups, almost equally reprehensible with that of indiscriminate distribution, is that of placing the groups and thickets in the recesses, instead of chiefly employing them opposite the salient points. The effect of this mode is the very reverse of what is intended; for, instead of varying the outline, it tends to render it more uniform by diminishing the depth of recesses, and approximating the whole more nearly to an even line. The way to vary an even or straight line or lines, is here and there to place constellations of groups against it (fig. 649); and a line already varied is to be rendered more so, by placing large groups against the prominences (a) to render them more prominent; and small groups (b), here and there in the recesses, to vary their forms and conceal their real depths.” [Fig. 47]

- Part III, Book III, Chapter V (p. 965)