Park

(Parke)

See also: Deer park, Public garden

History

The term park denotes both private and public expanses of ground. Eighteenth-century writers used park to refer exclusively to private grounds often enclosed by fences, walls, or ha-has; if devoted to keeping deer, it was sometimes called a deer park. Early nineteenth-century lexicographers continued to stress the definition of park as an expanse of private property, although Noah Webster in 1828 noted that parks also designated army encampments, perhaps anticipating the term’s increasing association with public grounds. Writers also focused upon the material advantages of parks, which included the production of timber in addition to grazing land. It is clear from treatises that parks also fulfilled aesthetic and symbolic functions.

J. C. Loudon, for example, stated in 1826 that a park added “grandeur and dignity to the mansion.” The notion of park as part of a large estate was closely connected to eighteenth-century British land practices, and, in particular, to the idea that land ownership provided both prestige and economic security. [1] The concept translated to America despite differences in landholding practices and in the legal system. As landscape gardener A. J. Downing noted in 1851, Americans generally would have much smaller parks than their British counterparts because inheritable land and money typically were divided among descendants instead of passing only to the first son, as was the case in Great Britain.

One of the earliest documented private parks in North America, dating from the period of British colonization, was the park that surrounded the Governor’s Palace in Williamsburg, Va., begun in 1699 [Fig. 1]. Hugh Jones, when describing the grounds of the College of William and Mary (1722), distinguished between the gardens immediately surrounding the building and those located in the larger 150-acre park. Nineteenth-century treatise writers maintained this distinction between gardens that were situated near the house and parks that encompassed the outlying area.

Writers of garden treatises, including Downing, specified how to arrange the key components of a park–grassy areas, woods, rolling hills, and water and how to establish desirable views. As styles in gardening changed, so did the arrangement of parks. Loudon in 1826 contrasted parks executed in the ancient or geometric style, which were “subdivided into fields . . . enclosed in walls or hedges,” with parks done in the modern or natural style “to resemble” the landscape of a “scattered forest.” One key aspect of parks executed in the latter style was the introduction of plantations or belts of trees to unify the landscape visually with patterns of lines of light and shadow formed by groupings of trees. Practitioners of the modern style, such as Downing, were concerned with creating discrete boundaries for parks: they often relied upon plantings either to define or to occlude views.

Landowners, such as William Hamilton, took the existing topography of their estates and manipulated it to fit the prevailing aesthetic. Views of late eighteenth-century estates often featured smooth lawns punctuated with clumps of trees and woods [Fig. 2]. In country house portraits, trees were often important elements—framing the house or drawing the viewer’s attention to the background. This emphasis paralleled treatise writers’ concern with trees as key components in park designs [Fig. 3]. Downing argued that artfully sited large trees added nobility, dignity, and a sense of age to a park, and he believed that such trees allowed American landscapes to rival those of the English.

Public parks, open landscaped spaces under government control, accommodated a wide variety of functions. Generally located in urban settings, many eighteenth- and nineteenth-century parks evolved from land originally set aside for commons, city squares, bowling greens, or other forms of pleasure grounds (see Common). Pierre-Charles L’Enfant described his plan for the national Mall in Washington, D.C., as a “place of general resort.”[2] With the growth of towns and cities in the first half of the nineteenth century and attendant fears of crowding and disease, civic improvement campaigners repeatedly expressed a desire to designate green spaces or parks that could act as “lungs” to bring in fresh air and mitigate toxic urban ills. Moreover, with the marked popularity of rural cemeteries in the 1840s, it became evident that urban populations were interested in open spaces. Public spaces were called parks early in America, but were also described as public grounds, public gardens, pleasure grounds, or pleasure gardens, to underscore either their accessibility to citizens or their leisure function.

A desire for sites of public commemoration also stimulated the development of public parks. The designation of the national Mall in Washington, D.C., as a park was linked intimately with the mission of public education envisioned by its founders. For example, in 1851 Downing described the Mall as a “sylvan museum”—an institution that would shape public taste in landscaping and in the selection of trees and plants.[3]

As was the case with many city parks, the land for present-day City Hall Park in New York originally was set aside as a common early in the city’s history. In 1803, when City Hall was erected on a site next to it, this land was designated as a park. Ornamented with gates, fountains, and plantings, it provided an elegant setting for the public building, according to the descriptions of William Dickinson Martin (1809) and John Lambert (1816), and a printed view of the park area (c. 1849) [Fig. 4]. Similarly, the oval Union Park in New York, often illustrated, had a large central fountain [Fig. 5]. Both parks featured broad walks and trees and shrubs. In these parks and others, significant goals of civic improvement—clean water, fresh air, green spaces—were united.[4] Bowling Green [Fig. 6] and Battery Park [Fig. 7] are two more New York public parks that date from the early eighteenth century.

Although New York City’s most important park, Central Park, was not designed until 1856, the idea for large-scale open space for the city dates much earlier. In 1811, the Streets Commission of New York produced a survey of the city, plotted by John Randel, Jr., to serve as a template for future development, and it put into place the grid that today still distinguishes the city. This grid also included open spaces, most significantly a “Grand Parade,” 240 acres bounded by Third and Seventh Avenues, and 23rd and 34th Streets, and this area was intended for military exercise, assembly, and, if necessary, “the force destined to defend the City.”[5] The concept of open space in the city was taken up again in the late 1840s and early 1850s, perhaps most notably by Downing in the Horticulturist. Claiming that the city’s existing parks were inadequate for the task of providing “exercise and refreshment of her jaded citizens,” Downing pushed for the creation of a large park, more than five hundred acres, to be located between 39th Street and the Harlem River. He proposed that it contain, among other attractions, carriage rides, monumental sculpture, water works, and walks set within green fields. Although Downing did not live to see this vision realized, his proposal anticipated Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux’s Central Park, and more generally, the American park movement.[6]

-- Anne L. Helmreich

Texts

Usage

- Penn, William, 9 April 1687, describing Pennsbury Manor, country estate of William Penn, near Philadelphia, Pa. (quoted in Thomforde 1986: 47)[7]

- “tis pitty a pale did not cross ye neck half way towards ye south point, for the beginning of a Park.”

- Jones, Hugh, 1722, describing the College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, Va. (1956: 67)[8]

- “It is approached by a good walk, and a grand entrance by steps, with good courts and gardens about it, with a good house and apartments for the Indian Master and his scholars, and outhouses; and a large pasture enclosed like a park with about 150 acres of land adjoining, for occasional uses.”

- Hamilton, Alexander, 26 June 1744, describing a garden near Albany, N.Y. (1948: 63)[9]

- “Mr. M——s [Milne] and I dined att his house and were handsomly entertained with good viands and wine. After dinner he showed us his garden and parks, and M——s [Milne] got into one of his long harangues of farming and improvement of ground.”

- Fisher, Daniel, 25 May 1755, describing the Proprietor’s Garden, Philadelphia, Pa. (quoted in Pecquet du Bellet 1907: 2:802)[10]

- “descending from the House is a neat little Park tho’ I am told there are no Deer in it.”

- Burnaby, Rev. Andrew, 1760, describing a park and garden near the Passaic River, N.J. (1775: 57)[11]

- “I went down two miles farther to the park and gardens of . . . colonel Peter Schuyler. In the gardens is a very large collection of citrons, oranges, limes, lemons, balsams of Peru, aloes, pomegranates, and other tropical plants; and in the park I saw several American and English deer, and three or four elks or moose-deer.”

- Fithian, Philip Vickers, 31 December 1773, describing Nomini Hall, Westmoreland County, Va. (1943: 59)[12]

- “Mrs. Carter told the Colonel that he must not think her setled (for they have been for a long time from this place in the City Williamsburg, and only left it about a year and a half ago) till he made her a park and stock’d it.”

- Hamilton, William, April 1779, describing the Woodlands, seat of William Hamilton, near Philadelphia, Pa. (quoted in Madsen 1988: A2)[13]

- “I have just been making some considerable Improvements at the Woodlands. . . . You may recollect the Ground is Hill ’n Dale Woodland and plain and therefore well enough calculated to make a small parke, and I am endeavoring to give it as much as possible a parkish Look.” [Fig. 8]

- Chastellux, François Jean, Marquis de, 1780–82, describing a garden on the Pamunkey River, Va. (1787: 2:12)[14]

- “embellished with a garden, laid out in the English style. It is even pretended, that this kind of park, through which the river flows, yields not in beauty to those, the model of which the French have received from England, and are now imitating with such success.”

- Washington, George, 18 August 1785, describing Mount Vernon, plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, Va. (Jackson and Twohig, eds., 1978: 4:184)[15]

- “Began with James and Tom to work on my Park fencing.”

- Morse, Jedidiah, 1789, describing Mount Vernon, plantation of [[[George Washington]], Fairfax County, Va. ([1789] 1970: 381) [16]

- “A small park on the margin of the river, where the English fallow-deer, and the American wild-deer are seen through the thickets, alternately with the vessels as they are sailing along, add a romantic and picturesque appearance to the whole scenery.”

- L’Enfant, Pierre-Charles, 22 June 1791, describing Washington, D.C. (quoted in Reps 1967: 17)[17]

- “I placed the three grand Department of States contiguous to the principle Palace and on the way leading to the Congressional House the gardens of the one together with the park and other improvement on the dependency are connected with the publique walk and avenue to the Congress house in a manner as most [must] form a whole as grand as it will be agreeable and convenient to the whole city which form [from] The distribution of the local [locale] will have an early access to this place of general resort and all along side of which may be placed play houses, room of assembly, academies and all such sort of places as may be attractive to the learned and afford diversion to the idle.”

- L’Enfant, Pierre-Charles, 4 January 1792, describing Washington, D.C. (quoted in Caemmerer 1950: 164) [18]

- “H. Grand Avenue, 400 feet in breadth, and about a mile in length, bordered with gardens, ending in a slope from the houses on each side. This Avenue leads to Monument A and connects the Congress Garden with the

- “I. President’s park and the

- “K. well-improved field.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, c. 1804, describing Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, Va. (Massachusetts Historical Society, Coolidge Collection)

- “The north side of Monticello below the Thoroughfare roundabout quite down to the river, and all Montalto above the thoroughfare to be converted into park & riding grounds, connected at the Thoroughfare by a bridge, open, under which the public road may be made to pass so as not to cut off the communication between the lower & upper park grounds.”

- Drayton, Charles, November 2, 1806, describing The Woodlands, seat of William Hamilton, near Philadelphia, Pa. (1806: 54–58)[19]

- “The Approach, its road, woods, lawn & clumps, are laid out with much taste & ingenuity. Also the location of the Stables; with a Yard between the house, stables, lawn of approach or park, & the pleasure ground or garden.

- "The Fences separating the Park-lawn from the Garden on one hand, & the office yard on the other, are 4 ft. 6 high. . . . The park lawn is not in good order, for lack of being fed upon. Its fences where it is not visible from the house, is of common posts & rails.

- ". . . . One is led into the garden from the portico, to the east or lefthand. or from the park, by a small gate contiguous to the house, traversing this walk, one sees many beauties of the landscape—also a fine statue, symbol of Winter, & age,—& a spacious Conservatory about 200 yards to the West of the Mansion. . . .

- "The Stable Yard, tho contiguous to the house, is perfectly concealed from it, the Lawn, & the Garden. . . . From the Cellar one enters under the bow window & into this Screen, which is about 6 or 7 feet square. Through these, we enter a narrow area, & ascend some few Steps [close to this side of the house,] into the garden—& thro the other opening we ascend a paved winding slope, which spreads as it ascends, into the yard. This sloping passage being a segment of a circle, & its two outer walls concealed by loose hedges, & by the projection of the flat roofed Screen of masonry, keeps the yard, & I believe the whole passage out of sight from the house—but certainly from the garden & park lawn."

- Foster, Sir Augustus John, c. 1807, describing Montpelier, plantation of James Madison, Montpelier Station, Va. (1954: 142)[20]

- “There are some very fine woods about Montpellier, but no pleasure grounds, though Mr. Madison talks of some day laying out space for an English park, which he might render very beautiful from the easy graceful descent of his hills into the plains below.”

- Latrobe, Benjamin Henry, 17 March 1807, describing the White House, Washington, D.C. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; hereafter CWF)

- “My idea is to carry the road below the hill under a Wall about 8 feet high opposite to the center of the president’s house. At this point, I should propose, at a future day to thrown an Arch, or Arches over the road in order to procure a private communication between the pleasure ground of the president’s house and the park which reaches to the river, and which will probably be also planted, and perhaps be open to the public.”

- Martin, William Dickinson, 21 May 1809, describing City Hall Park, New York, N.Y. (CWF)

- “St. Paul’s is on the same street, a little North of Trinity on the West side also, with an elegant steeple, tho’ too large for the rest of the building. It stands on a large triangular area, called the Park, rail’d in, & ornamented with trees & walks. Bridewell, the Alms House & County Jail, stand on the North Side of the Park, on the East is the New Theatre.”

- Lambert, John, 1816, describing City Hall Park, New York, N.Y. (2:58)[21]

- “A Court-house on a larger scale, and more worthy of the improved state of the city, is now building at the end of the Park, between the Broadway and Chatham-street, in a style of magnificence unequalled in many of the larger cities of Europe. . . . The Park, though not remarkable for its size, is, however, of service, by displaying the surrounding buildings to greater advantage; and is also a relief to the confined appearance of the streets in general. It consists of about four acres planted with elms, planes, willows, and catalpas; and the surrounding foot-walk is encompassed by rows of poplars: the whole is enclosed by a wooden paling. Neither the Park nor the Battery is very much resorted to by the fashionable citizens of New York, as they have become too common.”

- Lambert, John, 1816, describing the State House, Boston, Mass. (2:330)[21]

- “The new state-house is, perhaps, more indebted to its situation for the handsome appearance which it exhibits, than to any merit of the building itself. It is built upon part of the rising ground upon which Beacon Hill is situated, and fronts the park, an extensive common planted with a double row of trees along the borders. . . .

- “The Park was formerly a large common, but has recently been enclosed, and the borders planted with trees. On the east side there has been for many years a mall, or walk, planted with a double row of large trees, somewhat resembling that in St. James’s Park, but scarcely half its length. It affords the inhabitants an excellent promenade in fine weather. At the bottom of the park is a branch of the harbour; and along the shore, to the westward, are several extensive rope-walks built upon piers.”

- Hodgeson, Adam, 1819, describing Natchez, Miss. (quoted in Lockwood 1934: 2:389)[22]

- “Their houses are spacious and handsome and their grounds laid out like a forest park.”

- Bryant, William Cullen, 25 August 1821, describing the Vale, estate of Theodore Lyman, Waltham, Mass. (1975: 108–9)[23]

- “He took me to the seat of Mr. Lyman. . . . It is a perfect paradise. . . . North of the house was a park, with a few American deer in it and a large herd of spotted deer—a beautiful animal imported from Bengal.” [Fig. 9]

- Peale, Charles Willson, c. 1825, describing Wye House, estate of Col. Edward Lloyd, Talbot County, Md. (Miller, Hart, and Ward, eds., 2000: 5:147)[24]

- “The Coll. is possessed of immence property, he had 400 Ars. of land in a park to keep Deer, round which was a fence of 20 rails high, Maise were planted within for sustenance of his deer.”

- Anonymous, June 1829, describing City Hall Park, New York, N.Y. (The Casket 4: 241)

- “The City Hall of New York, is situated at the northern extremity, or base, of a triangular enclosure of four acres, called the ‘Park.’ The eastern and western sides are respectively bounded by Chatham street and Broadway, which here meet in a point near St. Paul’s church.

- “The approach from the south along Broadway, is peculiarly striking. The front and west end of the building present an angular view between the luxuriant foliage of trees surrounding the Park; while the brilliant whiteness of the facade, in contrast with the placid verdure of the lawn, in front, produces a luminous and aerial effect that fascinates every spectator.” [Fig. 10]

- Anonymous, June 1829, describing Sedgeley, seat of James C. Fisher and William Crammond, near Philadelphia, Pa. (The Casket 4: 265)

- “The natural advantages of Sedgeley Park are not frequently equalled even upon the banks of the romantic Schuylkill. From the height upon which the mansion is erected, it commands an interesting and extensive view. . . .

- “In the arrangement of the grounds the proprietor has been peculiarly happy. The park exhibits the marks of cultivation and taste, and the mansion is beautifully shaded with the native and luxuriant forest trees of the country.” [Fig. 11]

- Dearborn, H.A.S., 1832, describing Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, Mass. (quoted in Harris 1832: 84)[25]

- “The general appearance of the whole grounds, should be that of a well-managed park, and the lots only so far ornamented with shrubs and flowers, as to constitute rich borders to the avenues and pathways, without giving to them the aspect of a dense and wild coppice, or a neglected garden, whose trees and plants have so multiplied and interlaced their roots and branches, as to completely destroy all that airiness, grace, and luxuriance of growth, which good taste demands.”

- Bryant, William Cullen, 29 June 1832, describing the Jefferson Barracks, Jacksonville, Ill. (1975: 353) [23]

- “the Jefferson Barracks, a military station of the United States. . . . It is situated in a fine natural park of noble trees principally black oak which extends I am told for some miles back from the shore. The trees are at considerable distances from each other and the tops are spreading and full of foliage.”

- Martineau, Harriet, 1835, describing Cincinnati, Ohio (1838: 2:51)[26]

- “The proprietor has a passion for gardening, and his ruling taste seems likely to be a blessing to the city. He employs four gardeners, and toils in his grounds with his own hands. His garden is on a terrace which overlooks the canal, and the most park like eminences form the background of the view. Between the garden and the hills extend his vineyards, from the produce of which he has succeeded in making twelve kinds of wine, some of which are highly praised by good judges.”

- Downing, A. J., January 1837, “Notices on the State and Progress of Horticulture in the United States,” describing Hyde Park, seat of Dr. David Hosack, on the Hudson River, N.Y. (Magazine of Horticulture 3: 5)[27]

- “The most distinguished amateur and patron of gardening, in every sense of the word, in this state, was the late Dr. Hosack. Hyde '''Park''', on the Hudson, the seat of this gentleman, has been probably the best specimen of a highly improved residence in the United States . . . the park large, well wooded, and intersected by a fine stream.”

- Adams, Rev. Nehemiah, 1838, describing Boston Common, Boston, Mass. ([Adams] 1838: 22)[28]

- “Much as public squares, and parks, and avenues, and fountains contribute to the beauty of a city, they are no less necessary to its salubrity. It was not intended by the Creator that the habitations of men should be piled upon each other, as they are in some cities, almost like boxes of merchandize in a warehouse; and he has made no provision for the security of life and health, under the circumstances which preclude the supply of an abundance of fresh and pure air.”

- Willis, Nathaniel Parker, 1840, describing New York, N.Y. ([1840] 1971: 151)[29]

- “The present City Hall was erected in 1803, at an expense of half a million of dollars. . . . When the trees of the park are in full leaf, it is difficult to get an entire view of it.

- “The park is the centre of New York, and its two most thronged and finest avenues from the two sides of it. Broadway, the much crowded and much praised Broadway, the Corso, the Toledo, the Regent Street, of New York, pours its tide of population past the western side of the verdant triangle, and, just at the park, its crowd and its bustle are thickest.”

- Buckingham, James Silk, 1841, describing New York, N.Y. (1:38–39)[30]

- “Of the public places for air and exercise with which the Continental cities of Europe are so abundantly and agreeably furnished, and which London, Bath, and some other of the larger cities of England contain, there is a marked deficiency in New-York. Except the Battery, which is agreeable only in summer—the Bowling Green is a confined space of 200 feet long by 150 broad; the Park, which is a comparatively small spot of land (about ten acres only) in the heart of the city, and quite a public thoroughfare; Hudson Square, the prettiest of the whole, but small, being only about four acres; and the open space within Washington Square, about nine acres, which is not yet furnished with gravel-walks or shady trees—there is no large place in the nature of a park, or public garden, or public walk, where persons of all classes may take air and exercise. This is a defect which, it is hoped, will ere long be remedied, as there is no country, perhaps, in which it would be more advantageous to the health and pleasure of the community than this to encourage, by every possible means, the use of air and exercise to a much greater extent than either is at present enjoyed.”

- Dickens, Charles, 1842, describing Yale College, New Haven, Conn. (p. 94)[31]

- “New Haven, known as the City of Elms, is a fine town. Many of its streets (as its alias sufficiently imports) are planted with rows of grand old elm-trees; and the same natural ornaments surround Yale College, an establishment of considerable eminence and reputation. The various departments of this Institution are erected in a kind of park or common in the middle of the town, where they are dimly visible among the shadowing trees. The effect is very like that of an old cathedral yard in England; and when their branches are in full leaf, must be extremely picturesque.” [Fig. 12]

- Barber, John Warner, and Henry Howe, 1844, describing Point Breeze, the estate of Joseph Bonaparte (Count de Survilliers), Bordentown, N.J. (pp. 102–3)[32]

- “The park and grounds of the Count comprise about fourteen hundred acres, which, from a wild and impoverished tract, he has converted into a place of beauty, blending the charms of woodland and plantation scenery with a delightful water-prospect. . . . While here, his time was occupied in planning and executing improvements upon his grounds. He did not mingle in society; but was frequently seen walking through his park, attending to his workmen, or, with hatchet in hand, lopping branches from the trees.” [Fig. 13]

- Kirkbride, Thomas S., April 1848, describing the pleasure grounds and farm of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, Philadelphia, Pa. (Journal of Insanity 4: 348)[33]

- “The pleasure grounds of the two sexes are very effectually separated on the eastern side, by the deer-park, surrounded by a high palisade fence, but the Park itself is so low that it is completely overlooked from both sides; and the different animals in it are in full viewfrom the adjoining grounds used by the patients of both sexes.”

- Downing, A. J., October 1848, describing Geneseo, seat of James S. Wadsworth, Genesee River Valley, N.Y. (Horticulturist 3: 164–65)

- “And what a prospect! The whole of that part of the valley embraced by the eye—say a thousand acres—is a park, full of the finest oaks,—and such oaks as you may have dreamed of, (if you love trees,) or, perhaps, have seen in pictures by CLAUDE LORRAINE, or our own DURAND; but not in the least like those which you meet every day in your woodland walks through the country at large. Or rather, there are thousands of such as you may have seen half a dozen examples of in your own country. . . .

- “No underwood, no bushes, no thickets; nothing but single specimens or groups of giant old oaks, (mingled with, here and there, an elm) with level glades of broad meadow beneath them! An Englishman will hardly be convinced that it is not a park, planted by the skilful hand of man hundreds of years ago.

- “This great meadow park is filled with herds of the finest cattle—the pride of the home-farm.”

- Downing, A. J., 1849, describing Livingston Manor, seat of Mary Livingston, on the Hudson River, N.Y. (p. 46)[34]

- “The mansion stands in the midst of a fine park, rising gradually from the level of a rich inland country, and commanding prospects for sixty miles around. The park is, perhaps, the most remarkable in America, for the noble simplicity of its character, and the perfect order in which it is kept. The turf is, everywhere, short and velvet-like, the gravel-roads scrupulously firm and smooth, and near the house are the largest and most superb evergreens.”

- Loudon, J. C., 1850, describing St. John’s Park, New York, N.Y. (p. 332)[35]

- “856. Public Gardens....

- “At New York. . . . St. John’s Park is of considerable extent, and has lately been thrown open to the inhabitants: it is tastefully and very judiciously planted, with the ornamental trees and shrubs indigenous to the country. (Gard. Mag., vol. iii. p. 347.)”

- Hovey, C. M., September 1850, “Notes on Gardens and Gardening in the neighborhood of Boston,” describing Bellmont Place, residence of John Perkins Cushing, Watertown, Mass. (Magazine of Horticulture 16: 412)

- “The new and elegant mansion, so long vacant, is now occupied by the proprietor, and an air of liveliness, which they did not before possess, is now communicated to the park, the pleasure-ground and the garden. . . . The vast expanse of park, which adds so much to the character of the old English residence, would possess only half the attraction it now does, but for the herds of deer which traverse its bounds, giving life and animation to the scene.”

- Downing, A. J., 1851, describing plans for improving the public grounds of Washington, D.C. (quoted in Washburn 1967: 54–55)[36]

- “My object in this Plan has been three-fold:

- “1st: To form a national Park, which should be an ornament to the Capital of the United States; 2nd: To give an example of the natural style of Landscape Gardening which may have an influence on the general taste of the Country. . . .

- “1st: The President’s Park or Parade “This comprises the open Ground directly south of the President’s House. Adopting suggestions made me at Washington I propose to keep the large area of this ground open, as a place for parade or military reviews, as well as public festivities or celebrations. A circular carriage drive 40 feet wide and nearly a mile long shaded by an avenue of Elms, surrounds the Parade, while a series of foot-paths, 10 feet wide, winding through thickets of trees and shrubs, forms the boundary to this park, and would make an agreeable shaded promenade for pedestrians....

- “2nd: Monument Park

- “This comprises the fine plot of ground surrounding the Washington monument and bordered by the Potomac. To reach it from the President’s Park I propose to cross the canal by a wire suspension bridge, sufficiently strong for carriages, which would permit vessels of moderate size to pass under it, and would be an ornamental feature in the grounds. I propose to plant Monument Park wholly with American trees, of large growth, disposed in open groups, so as to al[l]ow of fine vistas of the Potomac river. . . .

- “4th: Smithsonian Park or Pleasure Grounds

- “An arrangement of choice trees in the natural style, the plots near the Institution would be thickly planted with the rarest trees and shrubs, to give greater seclusion and beauty to its immediate precincts. . . .

- “6th: The Botanic Garden...

- “The pleasing natural undulations of surface, where they occur, I propose to retain, instead of expending money in reducing them to a level. The surface of the Parks, generally, should be kept in grass or lawn, and mown by the mowing machine used in England, by which, with a man and horse, the labor of six men can be done in one day. . . .

- “A national Park like this, laid out and planted in a thorough manner, would exercise as much influence on the public taste as Mount Auburn Cemetery near Boston, has done. Though only twenty years have elapsed since that spot was laid out, the lesson there taught has been so largely influential that at the present moment the United States, while they have no public parks, are acknowledged to possess the finest rural cemeteries in the world. The Public Grounds at Washington treated in the manner I have here suggested, would undoubtedly become a Public School of Instruction in every thing that relates to the tasteful arrangement of parks and grounds, and the growth and culture of trees, while they would serve, more than anything else that could be devised, to embellish and give interest to the Capital. The straight lines and broad Avenues of the streets of Washington would be pleasantly relieved and contrasted by the beauty of curved lines and natural groups of trees in the various parks. By its numerous public buildings and broad Avenues, Washington will one day command the attention of every stranger, and if its un-improved public grounds are tastefully improved they will form the most perfect background or setting to the City, concealing many of its defects and heightening all its beauties.” [Fig. 14]

- Downing, A. J., August 1851, “The New-York Park” (Horticulturist 6: 345–49)[37]

- “THE leading topic of town gossip and newspaper paragraphs just now, in New-York, is the new park proposed by MAYOR KINGSLAND. Deluded New-York has, until lately, contented itself with the little door-yards of space—mere grass plats of verdure, which form the squares of the city, in the mistaken idea that they are parks. . . .

- “Thanking MAYOR KINGSLAND most heartily for his proposed new park, the only objection we make to it is that it is too small. One hundred and sixty acres of park for a city that will soon contain three-quarters of a million of people? It is only a child’s play-ground. . . .

- “Looking at the present government of the city as about to provide, in the Peoples’ Park, a breathing zone, and healthful place for exercise for a city of half a million of souls, we trust they will not be content with the limited number of acres already proposed. Five hundred acres is the smallest area that should be reserved for the future wants of such a city, now, while it may be obtained. Five hundred acres may be selected between 39th-street and the Harlem river, including a varied surface of land, a good deal of which is yet waste area, so that the whole may be purchased at something like a million of dollars. In that area there would be space enough to have broad reaches of park and pleasure-grounds, with a real feeling of the breadth and beauty of green fields, the perfume and freshness of nature. In its midst would be located the great distributing reservoirs of the Croton aqueduct, formed into lovely lakes of limpid water, covering many acres, and heightening the charm of the sylvan accessories by the finest natural contrast. In such a park, the citizens who would take excursions in carriages, or on horseback, could have the substantial delights of country roads and country scenery, and forget for a time the rattle of the pavements and the glare of brick walls. Pedestrians would find quiet and secluded walks when they wished to be solitary, and broad alleys filled with thousands of happy faces, when they would be gay. The thoughtful denizen of the town would go out there in the morning to hold converse with the whispering trees, and the wearied tradesmen in the evening, to enjoy an hour of happiness by mingling in the open space with ‘all the world.’

- “The many beauties and utilities which would gradually grow out of a great park like this, in a great city like New-York, suggest themselves immediately and forcibly. Where would be found so fitting a position for noble works of art, the statues, monuments, and buildings commemorative at once of the great men of the nation, of the history of the age and country, and the genius of our highest artists?

- “We have said nothing of the social influence of such a great park in New-York. But this is really the most interesting phase of the whole matter. . . .

- “Even upon the lower platform of liberty and education that the masses stand in Europe, we see the elevating influences of a wide popular enjoyment of galleries of art, public libraries, parks and gardens, which have raised the people in social civilization and social culture to a far higher level than we have yet attained in republican America. And yet this broad ground of popular refinement must be taken in republican America, for it belongs of right more truly here, than elsewhere. It is republican in its very idea and tendency. It takes up popular education where the common school and ballot-box leave it, and raises up the working-man to the same level of enjoyment with the man of leisure and accomplishment. The higher social and artistic elements of every man’s nature lie dormant within him, and every laborer is a possible gentleman, not by the possession of money or fine clothes—but through the refining influence of intellectual and moral culture.”

- Downing, A. J., December 1851, “State and Prosperity of Horticulture” (Horticulturist 6: 540)[38]

- “From cemeteries we naturally rise to public parks and gardens. As yet our countrymen have almost entirely over-looked the sanitary value and importance of these breathing places for large cities, or the powerful part which they may be made to play in refining, elevating, and affording enjoyment to the people at large. . . . The plan [for a public ground in Washington] embraces four or five miles of carriage-drive—walks for pedestrians—ponds of water, fountains and statues—picturesque groupings of trees and shrubs, and a complete collection of all the trees that belong to North America. It will, if carried out as it has been undertaken, undoubtedly give a great impetus to the popular taste in landscape-gardening and the culture of ornamental trees; and as the climate of Washington is one peculiarly adapted to this purpose—this national park may be made a sylvan museum such as it would be difficult to equal in beauty and variety in any part of the world.”

- Mark Twain, 26 October 1853, describing Fairmount Waterworks, Philadelphia, Pa. (quoted in Gibson 1988: 2)[39]

- “Seeing a park at the foot of the hill, I entered—and found it one of the nicest little places about.” [Fig. 15]

Citations

- Chambers, Ephraim, 1741–43, Cyclopaedia (2:n.p.)[40]

- “PARK,* PARCUS, a large inclosure, privileged for wild beasts of chase, either by the king’s grant, or by prescription.

- “*The word is originally Celtic, it signifies an inclosure, or place shut up with walls.

- “Manwood defines a park a place of privilege for beasts of venery, and other wild beasts of the forest, and of chase, tam sylvestres quam campestres.—A park differs from a forest in that, as Crompton observes, a subject may hold a park by prescription, or the king’s grant, which he cannot do by a forest. See FOREST.

- “A park differs from a chase also; for that a park must be enclosed; if it lie open, it is a good cause of seizing it into the king’s hand; as a free chase may be, if it be enclosed. Nor can the owner have any action against such as hunt in his park, if it lie open. See CHASE.

- “Du Cange refers the invention of parks to king Henry I. of England; but Spelman shews, it is much more ancient; and was in use among the Anglo-Saxons. Zosimus assures us, the ancient kings of Persia had parks.

- “PARK is also used for a moveable pallisade set up in the fields to inclose sheep in to feed, and rest in during the night. See HURDLES.

- “The shepherds shift their park, from time to time, to dung the ground, one part after another.”

- Whately, Thomas, 1770, Observations on Modern Gardening ([1770] 1982: 157, 182–83)[41]

- “A garden is intended to walk or to sit in, which are circumstances not considered in riding; a park comprehends all the uses of the other two; and these uses determine the proportional extent of each; a large garden would be but a small park; and the circumference of a considerable park but a short riding.

- “A park and a garden are more nearly allied, and can therefore be accommodated to each other, without any disparagement to either. . . .

- “The affinity of the two subjects is so close, that it would be difficult to draw the exact line of separation between them: gardens have lately encroached very much both in extent and in style on the character of a park; but still there are scenes in the one, which are out of the reach of the other; the small sequestered spots which are agreable in a garden, would be trivial in a park; and the spacious lawns which are among the noblest features of the latter, would in the former fatigue by their want of variety; even such as being of a moderate extent may be admitted into either, will seem bare and naked, if not broken in the one; and lose much of their greatness, if broken in the other. The proportion of a part to the whole, is a measure of its dimensions: it often determines the proper size for an object, as well as the space fit to be allotted to a scene; and regulates the style which ought to be assigned to either.

- “But whatever distinctions the extent may occasion between park and garden, a state of highly cultivated nature is consistent with each of their characters; and may in both be of the same kind, though in different degrees. The same species of preservation, of ornament, and of scenery, may be introduced; and though a large portion of a park may be rude; and the most romantic scenes are not incompatible with its character.”

- Sheridan, Thomas, 1789, A Complete Dictionary of the English Language (n.p.)[42]

- “PARK, pa’rk. s. A piece of ground inclosed and stored with deer and other beasts of chase.”

- Repton, Humphry, 1803, Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (pp. 13, 93–94)[43]

- “There is no error more prevalent in modern gardening, or more frequently carried to excess, than taking away hedges to unite many small fields into one extensive and naked lawn, before plantations are made to give it the appearance of a park; and where ground is subdivided by sunk fences, imaginary freedom is dearly purchased at the expence of actual confinement. . . .

- “The chief beauty of a park consists in uniform verdure; undulating lines contrasting with each other in variety of forms; trees so grouped as to produce light and shade to display the varied surface of the ground; and an undivided range of pasture. . . .

- “The farm, on the contrary, is for ever changing the colour of its surface in motley and discordant hues; it is subdivided by straight lines of fences. The trees can only be ranged in formal rows along the hedges; and these the farmer claims a right to cut, prune, and disfigure.”

- Nicol, Walter, 1812, The Planter’s Kalendar (p. 378)[44]

- “It may, however, be humbly suggested, that the Park, or the Lawn, should never be daubed too full of groups, or of single plants. When there are too many put in, the whole park acquires a confined air and appearance; and, whatever be the intrinsic worth of the plants individually considered, the eye turns from the appearance with dislike.”

- Loudon, J. C., 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (pp. 1021, 1028)[45]

- “7265. The park is a space devoted to the growth of timber, pasturage for deer, cattle, and sheep, and for adding grandeur and dignity to the mansion. On its extent and beauty, and on the magnitude and architectural design of the house, chiefly depend the reputation and character of the residence. In the geometric style, the more distant or concealed parts were subdivided into fields, surrounded by broad stripes or double rows, enclosed in walls or hedges, and the nearer parts were chiefly covered with wood, enclosing regular surfaces of pasturage. In the modern style, the scenery of a park is intended to resemble that of a scattered forest, the more polished glades and regular shapes of lawn being near the house, and the rougher parts towards the extremities. The paddocks or small enclosures are generally placed between the family stables and the farm, and form a sort of intermediate character. . . .

- “7313. Public parks, or equestrian promenades, are valuable appendages to large cities. Extent and a free air are the principle requisites, and the roads should be arranged so as to produce few intersections; but at the same time so as carriages may make either the tour of the whole scene, or adopt a shorter tour at pleasure. In the course of long roads, there ought to be occasional bays or side expansions to admit of carriages separating from the course, halting or turning. Where such promenades are very extensive, they are furnished with places of accommodation and refreshment, both for men and horses; this is a valued part of their arrangement for occasional visitors from a distance, or in hired vehicles.”

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (n.p.)[46]

- “PARK, n. [Sax. parruc, pearruc; Scot. parrok; W. parc; Fr. id.; It. parco; Sp. parque; Ir. pairc; G. Sw. park; D. perk. . . .]

- “A large piece of ground inclosed and privileged for wild beasts of chase, in England, by the king’s grant or by prescription. To constitute a park, three things are required; a royal grant or license; inclosure by pales, a wall or hedge; and beasts of chase, as deer, &c.

- “Park of artillery, or artillery park, a place in the rear of both lines of an army for encamping the artillery, which is formed in lines, the guns in front, the ammunition-wagons behind the guns. . . . Encyc.

- “Park of provisions, the place where the sutlers pitch their tents and sell provisions, and that where the bread wagons are stationed.”

- Johnson, George William, 1847, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening (p. 418)[47]

- “PARK, in the modern acceptation of the word, is an extensive adorned inclosure surrounding the house and gardens, and affording pasturage either to deer or cattle.”

- Downing, A. J., October 1848, “A Talk About Public Parks and Gardens” (Horticulturist 3: 156–57)[48]

- “Make the public parks or pleasure grounds attractive by their lawns, fine trees, shady walks and beautiful shrubs and flowers, by fine music, and the certainty of ‘meeting everybody,’ and you draw the whole moving population of the town there daily. . . .

- “you must remember that there is no forced intercourse in the daily reunions in a public garden or park. There is room and space enough for pleasant little groups or circles of all tastes and sizes, and no one is necessarily brought into contact with uncongenial spirits; while the daily meeting of families, who ought to sympathise, from natural congeniality, will be more likely to bring them together than any other social gatherings. Then the advantage to our fair country-women— health and spirits, of exercise in the pure open air, amid the groups of fresh foliage and flowers, with a chat with friends, and pleasures shared with them, as compared with a listless lounge upon a sofa at home, over the last new novel or pattern of embroidery! . . .

- “Judging from the crowds of people in carriages, and on foot, which I find constantly thronging [[Greenwood Cemetery|Green-wood and Mount Auburn, I think it is plain enough how much our citizens, of all classes, would enjoy public parks on a similar scale. Indeed, the only drawback to these beautiful and highly kept cemeteries, to my taste, is the gala-day air of recreation they present. People seem to go there to enjoy themselves, and not to indulge in any serious recollections or regrets.”

- Downing, A. J., 1849, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (pp. 31, 95, 109–11, 115–16, 169, 173, 219, 333)[34]

- “It must not be forgotten that, during all this period, or nearly six centuries, parks were common in England. . . .

- “Although these parks were more devoted to the preservation of game and the pleasures of the chase than to any other purpose, their existence was, we conceive, not wholly owing to this cause—but we look upon them as indicating that love of nature and that desire to retain beautiful portions of it as part of a residence, which form the ground-work of the taste for the modern or landscape gardening, since the latter is only an epitome of nature with the charms judiciously heightened by art.

- “And as the Avenue, or the straight line, is the leading form in the geometric arrangement of plantations, so let us enforce it upon our readers, the GROUP is equally the key-note of the Modern style. The smallest place, having only three trees, may have these pleasingly connected in a group; and the largest and finest park—the Blenheim or Chatsworth, of seven miles square, is only composed of a succession of groups, becoming masses, thickets, woods. . . .

- “One of the loveliest charms of a fine park is, undoubtedly, variation or undulation of surface. Everything, accordingly, which tends to preserve and strengthen this pleasing character, should be kept constantly in view. . . .

- “Where the grounds of the residence to be planted are level, or nearly so, and it is desirable to confine the view, on any or all sides, to the lawn or park itself, the boundary groups and masses must be so connected together as, from the most striking part or parts of the prospect (near the house for example) to answer this end. . . .

- “But where the house is so elevated as to command a more extensive view than is comprised in the demesne itself, another course should be adopted. The grounds planted must be made to connect themselves with the surrounding scenery. . . . Where the park joins natural woods, connexion is still easier, and where it bounds upon one of our noble rivers, lakes, or other large sheets of water, of course connexion is not expected; for sudden contrast and transition is there both natural and beautiful. . . .

- “Were it not that of late it [the linden tree] is so liable to insects, we could hardly say too much in its praise as a fine ornament for streets and public parks. There, its regular form corresponds well with the formality of the architecture; its shade affords cool and pleasant walks, and the delightful odor of its blossoms is doubly grateful in the confined air of the city. . . .

- “The beech is quite handsome and graceful when young, and when large it forms one of the heaviest and grandest of beautiful park trees. ...

- “When the Black walnut stands alone on a deep fertile soil it becomes a truly majestic tree; and its lower branches often sweep the ground in a graceful curve, which gives additional beauty to its whole expression. It is admirably adapted to extensive lawns, parks, or plantations, where there is no want of room for the attainment of its full size and fair proportions. . . .

- “In places of large extent there may be scenes in different portions of the park of totally different character; one simply beautiful, abounding with graceful and flowing lines, and another highly picturesque, and full of spirited breaks and variations.”

- Downing, A. J., January 1849, “On the Mistakes of Citizens in Country Life” (Horticulturist 3: 309)

- “If you wish for rural beauty, at a cheap rate, either on the grand or the moderate scale, choose a spot where the two features of home scenery are trees and grass. You may have five hundred acres of natural park—that is to say, fine old woods, tastefully opened, and threaded with walks and drives, for less cost, in preparation and annual outlay, than it will require to maintain five acres of artificial pleasure-grounds. A pretty little natural glen, filled with old trees, and made alive by a clear perennial stream, is often a cheaper and more unwearying source of enjoyment than the gayest flower garden. Not that we mean to disparage beautiful parks, pleasure-grounds, or flower gardens; we only wish our readers, about settling in the country, to understand that they do not constitute the highest and most expressive kind of rural beauty,—as they certainly do the most expensive.”

- Loudon, J. C., 1850, Encyclopaedia of Gardening (p. 329)[35]

- “841. Landscape-Gardening is practised in the United States on a comparatively limited scale; because, in a country where all men have equal rights, and where every man, however humble, has a house and garden of his own, it is not likely that there should be many large parks. The only splendid examples of park and hothouse gardening that, we trust, will ever be found in the United States, and ultimately in every other country, are such as will be formed by towns and villages, or other communities, for the joint use and enjoyment of all the inhabitants or members.”

- Jeffreys [pseud.], January 1850, “Critique on November Horticulturist” (Horticulturist 4: 311–12)[49]

- “A true country house should also have some appearance of rusticity—not vulgarity—but a keeping with all which surround it. Not castellated, nor magnificent; neither ostentatious nor pretending, but plain, dignified, quiet and unobtrusive; yet of ample dimensions, and exceeding convenience. Then, in park or lawn, on hill or plain, flanked with mossy foliage, and well kept grounds, it becomes a perfect picture in a finished landscape.”

- Downing, A. J., June 1850, “Our Country Villages” (Horticulturist 4: 540)[50]

- “The indispensable desiderata in rural villages of this kind [newly planned in the suburbs of a great city], are the following: 1st, a large open space, common, or park, situated in the middle of the village—not less than 20 acres; and better, if 50 or more in extent. This should be well planted with groups of trees, and kept as a lawn. The expense of mowing it would be paid by the grass in some cases; and in others a considerable part of the space might be enclosed with a wire fence, and fed by sheep or cows, like many of the public parks in England.

- “This park would be the nucleus or heart of the village, and would give it an essentially rural character. Around it should be grouped all the best cottages and residences of the place; and this would be secured by selling no lots fronting upon it of less than one-fourth of an acre in extent. . . .

- “After such a village was built, and the central park planted a few years, the inhabitants would not be contented with the mere meadow and trees, usually called a park in this country. By submitting to a small annual tax per family, they could turn the whole park, if small, or considerable portions, here and there, if large, into pleasure-grounds. In the latter, there would be collected, by the combined means of the village, all the rare, hardy shrubs, trees and plants usually found in the private grounds of any amateur in America.”

- Downing, A. J., March 1851, “The Management of large Country Places” (Horticulturist 6: 106–7)

- “The great and distinguishing beauty of England, as every one knows, is its parks. And yet the English parks are only very large meadows, studded with great oaks and elms—and grazed—profitably grazed, by deer, cattle and sheep. We believe it is a commonly received idea in this country, with those who have not travelled abroad, that English parks are portions of highly dressed scenery—at least that they are kept short by frequent mowing, etc. It is an entire mistake. The mown lawn with its polished garden scenery, is confined to the pleasure grounds proper—a spot of greater or less size, immediately surrounding the house, and wholly separated from the park by a terrace wall, or an iron fence, or some handsome architectural barrier. The park, which generally comes quite up to the house on one side, receives no other attention than such as belongs to the care of the animals that graze in it. As most of these parks afford excellent pasturage, and though apparently one wide, unbroken surface, they are really subdivided into large fields, by wire or other invisible fences, they actually pay a very fair income to the proprietor, in the shape of good beef, mutton and venison. ...

- “Of course, any thing like English parks, so far as regards extent, is almost out of the question here; simply because land and fortunes are wisely divided here, instead of being kept in large bodies, intact, as in England. Still, as the first class country-seats of the Hudson now command from $50,000 to $75,000, it is evident that there is a growing taste for space and beauty in the private domains of republicans. What we wish to suggest now, is, simply, that the greatest beauty and satisfaction may be had here, as in England—(for the plan really suits our limited means better,) by treating the bulk of the ornamental portion as open park pasture—and thus getting the greatest space and beauty at the least original expenditure, and with the largest annual profit. . . .

- “All that is to be borne in mind is, that the park may be as large as you can afford to purchase—for it may be kept up at a profit—while the pleasure-grounds and garden scenery, may, with this management, be compressed into the smallest space actually deemed necessary to the place—thereby lessening labor, and bestowing that labor, in a concentrated space, where it will tell.”

Images

Inscribed

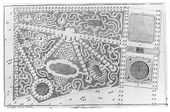

Batty Langley, "Design of a Small Garden Situated in a Park," in New Principles of Gardening, (1728), pl. XII.

Batty Langley, "Part of a Park Exhibiting their manner of Planting, after a more Grand manner than has been done before," in New Principles of Gardening, (1728), pl. XIII.

Batty Langley, "Part of a Park Exhibiting their manner of planting, after a more grand manner than has been done before," in New Principles of Gardening, (1728), pl. XIV.

William Smith after Alexander Jackson Davis, View of St. John's Chapel, From the Park, 1829.

Anonymous, "View in the Meadow Park at Geneseo," in A. J. Downing, ed., The Horticulturist, 3, no. 4 (October 1848): pl. opp. p. 153.

Anonymous, "View in the Grounds at Hyde Park," in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, (1849), pl. opp. p. 45, fig. 1.

Anonymous, "Plan of a Mansion Residence, laid out in the natural style," in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, (1849), p. 115, fig. 25.

A. J. Downing, Plan Showing Proposed Method of Laying Out the Public Grounds at Washington, 1851.

Anonymous, Study of trees in Park Scenery, in A. J. Downing, "Study of Park Trees," Horticulturist, vol. 6, no. 9 (September 1, 1851), pl. opp. p. 394.

Lewis Miller, Title page, Sketchbook of Landscapes in the State of Virginia, (1853).

A. J. Downing, Plan Showing Proposed Method of Laying Out the Public Grounds at Washington, 1851.

Associated

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Horsdumonde, the House of Colonel Henry Skipwith, Cumberland County, Virginia, June 14, 1796.

A. J. Downing, "Presidents Arch at the end of Penna Avenue," 1851.

Anonymous, "Mount Fordham—the Country Seat of Lewis G. Morris, Esq.," in A. J. Downing, ed., Horticulturist 6, no. 8 (Aug. 1, 1851): pl. opp. p. 345.

Attributed

Batty Langley, One of two "Designs for Gardens that lye irregularly to the grand House . . . ," in New Principles of Gardening, (1728), pl. X.

Batty Langley, One of two "Designs for Gardens that lye irregularly to the ground House . . .," in New Principles of Gardening (1728), pl. XI.

Batty Langley, "Variety of Lawns, or Openings, before a grand Front of a Building, into a Park, Forest, Common, &c." in New Principles of Gardening, (1728), pl. XVI.

Alexander Jackson Davis, Castle Garden, N. York, c. 1825–1828.

Anthony St. John Baker, "Front View of Mount Airy, Virginia," 1827, in Mémoires d’un voyageur qui se repose (1850), part IV, p. 520A.

Anthony St. John Baker, Mount Airy, Virginia; northeast front, 1827, in Mémoires d’un voyageur qui se repose (1850), part IV, p. 520A.

Notes

- ↑ Joseph S. Wood, The New England Village (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997), 65, view on Zotero.

- ↑ For a history of the development of American parks and civic ideology, see David Schuyler, The New Urban Landscape: The Redefinition of City Form in Nineteenth-Century America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986), view on Zotero. Also see George F. Chadwick, The Park and the Town: Public Landscape in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries (New York: F. A. Praeger, 1966), view on Zotero, and Galen Cranz, The Politics of Park Design: A History of Urban Parks in America (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1982), view on Zotero.

- ↑ For more about the history of the Mall, see Therese O’Malley, “Art and Science in American Landscape Architecture: The National Mall, Washington, D.C., 1791–1852” (Ph.D. diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1989), view on Zotero, and Richard Longstreth, ed., The Mall in Washington, 1791–1991 (Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Likewise, in Philadelphia, the construction of the Fairmount Park and Waterworks|Fairmount Waterworks was accompanied by the construction of a designed landscape, which rarely was referred to as a park in this period. For a history of Fairmount Park, see Jane Mork Gibson, “The Fairmount Waterworks,” Bulletin, Philadelphia Museum of Art 84 (summer 1988): 5–40, view on Zotero, and Theo B. White, Fairmount, Philadelphia’s Park (Philadelphia: Art Alliance Press, 1975), view on Zotero. H. M. Pierce Gallagher, in his monograph of Robert Mills, noted that the architect never referred to the site as Fairmount Park, but rather as the Philadelphia Water Works. H. M. Pierce Gallagher, Robert Mills, Architect of the Washington Monument, 1781–1855 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1935), 128, view on Zotero. Michael J. Lewis, “The First Design for Fairmount Park,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 130, no. 3 (July 2006): 283–97, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace, Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 421, view on Zotero.

- ↑ For an overview of the history of the park, see Roy Rosenzweig and Elizabeth Blackmar, The Park and the People: A History of Central Park (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1992), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Thomforde, "William Penn’s Estate at Pennsbury and the Plants of Its Kitchen Garden" (unpublished Master’s thesis, Public Horticulture Administration, University of Delaware, 1986), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Hugh Jones, The Present State of Virginia, From Whence Is Inferred a Short View of Maryland and North Carolina, ed. by Richard L. Morton (Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 1956), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alexander Hamilton, Gentleman’s Progress: The Itinerarium of Dr. Alexander Hamilton, 1744, ed. by Carl Bridenbaugh (Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 1948), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Louise Pecquet du Bellet, ed., Some Prominent Virginia Families, 4 vols (Lynchburg, Va.: J. P. Bell, 1907), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Andrew Burnaby, Travels through the Middle Settlements in North-America, in the Years 1759 and 1760, 2nd edn (London: Printed for T. Payne, 1775), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Philip Vickers Fithian, Journal & Letters of Philip Vickers Fithian, 1773-1774: A Plantation Tutor of the Old Dominion, ed. by Hunter D. Farish (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg, 1943), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Karen Madsen, "William Hamilton’s Woodlands", 1988, view on Zotero.

- ↑ François Jean Marquis de Chastellux, Travels in North America in the Years 1780, 1781, and 1782, 2 vols (London: G. G. J. and J. Robinson, 1787), view on Zotero.

- ↑ George Washington, The Diaries of George Washington, ed. by Donald Jackson and Dorothy Twohig, 6 vols (Charlottesville, Va.: University Press of Virginia, 1978), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jedidiah Morse, The American Geography; Or, A View of the Present Situation of the United States of America (Elizabeth Town, N.J.: Shepard Kollock, 1789), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John W. Reps, Monumental Washington, The Planning and Development of the Capital Center (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1967), view on Zotero.

- ↑ H. Paul Caemmerer, The Life of Pierre-Charles L’Enfant, Planner of the City Beautiful, The City of Washington (Washington, D.C.: National Republic Publishing Company, 1950), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Drayton, "The Diary of Charles Drayton I, 1806," 1806, Drayton Hall: A National Historic Trust Site, http://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:27554, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Sir Augustus John Foster, Jeffersonian America: Notes on the United States of America Collected in the Years 1805-1806-1807 and 1811-1812, ed. by Richard Beale Davis (San Marino, Calif.: Huntington Library, 1954), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 John Lambert, Travels through Canada, and the United States of North America in the Years 1806, 1807, and 1808, 2 vols (London: Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy, 1816), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alice B. Lockwood, ed., Gardens of Colony and State: Gardens and Gardeners of the American Colonies and of the Republic before 1840, 2 vols (New York: Charles Scribner’s for the Garden Club of America, 1931), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 William Cullen Bryant, The Letters of William Cullen Bryant, ed. by William Cullen II Bryant and Thomas G. Voss (New York: Fordham University Press, 1975), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Lillian B. Miller et al, eds., The Selected Papers of Charles Willson Peale and His Family: Charles Willson Peale: Artist in Revolutionary America, 1735-1791. Vol. 1; Charles Willson Peale, Artist as Museum Keeper, 1791-1810. Vol 2, Pts. 1-2; The Belfield Farm Years, 1810-1820. Vol. 3; The Autobiography of Charles Willson Peale. Vol. 5. (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1983–2000), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thaddeus William Harris, A Discourse Delivered before the Massachusetts Horticultural Society on the Celebration of Its Fourth Anniversary, October 3, 1832 (Cambridge, Mass.: E. W. Metcalf, 1832), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Harriet Martineau, Retrospect of Western Travel, 2 vols (London: Saunders and Otley, 1838), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Andrew Jackson Downing, "Notices on the State and Progress of Horticulture in the United States", The Magazine of Horticulture, 3 (1837), 1–10, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Nehemiah Adams, Boston Common (Boston: William D. Ticknor and H. B. Williams, 1842), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Nathaniel Parker Willis, American Scenery; Or, Land, Lake and River Illustrations of Transatlantic Nature (London: G. Virtue, 1840)

- ↑ James Silk Buckingham, America, Historical, Statistic, and Descriptive, 2 vols (New York: Harper, 1841), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Dickens, American Notes (Paris: Baudry’s European Library, 1842), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Warner Barber and Henry Howe, Historical Collections of the State of New Jersey; Containing a General Collection of the Most Interesting Facts, Traditions, Biographical Sketches, Anecdotes, &c. Relating to History and Antiquities, with Geographical Descriptions of Every Township in the State (Newark, N.J.: Benjamin Olds, 1844), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas S. Kirkbride, "Description of the Pleasure Grounds and Farm of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, with Remarks", The American Journal of Insanity, 4 (1848), 347–54, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America, 4th edn (Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, new ed., corr. and improved (London: Longman et al., 1850), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Wilcomb E. Washburn, "Vision of Life for the Mall", AIA Journal, 47 (1967), 52–59, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Andrew Jackson Downing, "The New-York Park", The Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste, 6 (1851), 345–49, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Andrew Jackson Downing, "The State and Prospects of Horticulture", The Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste, 6 (1851), 537–41, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jane Mork Gibson, "The Fairmount Waterworks’", Bulletin, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 84 (1988), 5–40, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Ephraim Chambers, Cyclopaedia, or An Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences. . . ., 5th edn, 2 vols (London: D. Midwinter et al, 1741), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Whately, Observations on Modern Gardening, 3rd edn (London: Garland, 1982), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas A. Sheridan, A Complete Dictionary of the English Language, Carefully Revised and Corrected by John Andrews...., 5th edn (Philadelphia: William Young, 1789), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Humphry Repton, Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (London: Printed by T. Bensley for J. Taylor, 1803), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Walter Nicol, The Planter’s Kalendar (Edinburgh: D. Willison for A. Constable, 1812), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, 4th edn (London: Longman et al, 1826), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ George William Johnson, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening, ed. by David Landreth (Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1847), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Andrew Jackson Downing, "A Talk About Public Parks and Gardens", The Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste, 3 (1848), 153–58, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jeffreys [pseud.], "Critique on the October Horticulturist", The Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste, 4 (1849), 268–71, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Andrew Jackson Downing, "Our Country Villages", The Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste, 4 (1850), 537–41, view on Zotero.