Difference between revisions of "Samuel Vaughan"

V-Federici (talk | contribs) m |

M-westerby (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{Person | ||

| + | |Birth Present=No | ||

| + | |Birth Date=April 23, 1720 | ||

| + | |Birth Circa=No | ||

| + | |Birth Concurrence=Exact | ||

| + | |Birth Questionable=No | ||

| + | |Birth HasEndDate=No | ||

| + | |Birth Present End=No | ||

| + | |Birth Circa End=No | ||

| + | |Birth Questionable End=No | ||

| + | |Death Present=No | ||

| + | |Death Date=1802 | ||

| + | |Death Circa=No | ||

| + | |Death Concurrence=Exact | ||

| + | |Death Questionable=No | ||

| + | |Death HasEndDate=No | ||

| + | |Death Present End=No | ||

| + | |Death Circa End=No | ||

| + | |Death Questionable End=No | ||

| + | |Keywords=Alley; Avenue; Bed; Clump; Fence; Grove; Hothouse; Kitchen garden; Lawn; Mall; Mound; Seat; Shrubbery; Square; View/Vista; Walk; Wall; Yard | ||

| + | |Other resources={{ExternalLink | ||

| + | |External link URL=http://id.loc.gov/authorities/names/n78053741.html | ||

| + | |External link text=Library of Congress Name Authority File | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | }} | ||

'''Samuel Vaughan''' (April 23, 1720–1802) was a London merchant and owner of sugar [[plantation]]s in Jamaica. An ardent supporter of the cause of American independence, Vaughan contributed to the development of several important American sites and institutions, including the [[State House Yard]] and the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia, where he also designed the popular [[pleasure ground]] known as [[Gray’s Garden]]. | '''Samuel Vaughan''' (April 23, 1720–1802) was a London merchant and owner of sugar [[plantation]]s in Jamaica. An ardent supporter of the cause of American independence, Vaughan contributed to the development of several important American sites and institutions, including the [[State House Yard]] and the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia, where he also designed the popular [[pleasure ground]] known as [[Gray’s Garden]]. | ||

| Line 69: | Line 94: | ||

==Other Resources== | ==Other Resources== | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[http://tclf.org/pioneer/samuel-vaughan/biography-samuel-vaughan The Cultural Landscape Foundation] | [http://tclf.org/pioneer/samuel-vaughan/biography-samuel-vaughan The Cultural Landscape Foundation] | ||

Latest revision as of 21:31, October 5, 2021

Overview

Birth Date: April 23, 1720

Death Date: 1802

Used Keywords: Alley, Avenue, Bed, Clump, Fence, Grove, Hothouse, Kitchen garden, Lawn, Mall, Mound, Seat, Shrubbery, Square, View/Vista, Walk, Wall, Yard

Other resources: Library of Congress Name Authority File;

Samuel Vaughan (April 23, 1720–1802) was a London merchant and owner of sugar plantations in Jamaica. An ardent supporter of the cause of American independence, Vaughan contributed to the development of several important American sites and institutions, including the State House Yard and the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia, where he also designed the popular pleasure ground known as Gray’s Garden.

History

During the 1740s Samuel Vaughan established extensive commercial enterprises in London, the West Indies, and the American colonies. He purchased large quantities of land and slaves in the vicinity of Montego Bay in Jamaica, where he established lucrative sugar plantations.[1] Vaughan strengthened his ties to America through marriage in 1747 to Sarah Hallowell (1727–1809), daughter of the wealthy Boston merchant, shipbuilder, and landowner Benjamin Hallowell.[2] Unlike his loyalist father-in-law, Vaughan was a passionate advocate of American liberty and a great admirer of George Washington. In London he was a member of the “Club of Honest Whigs”—a liberal coterie of intellectuals and religious dissenters (several of them, like Vaughan, were Unitarians) who met to discuss science, philosophy, and social and political reform.[3] At his home in the English village of Wanstead, Vaughan hosted visiting American patriots such as Benjamin Franklin, who became an intimate family friend, and Josiah Quincy Jr., to whom Franklin introduced Vaughan in 1774.[4] It was possibly at Wanstead that Vaughan developed the knowledge of landscape gardening that he later brought to America. Nearby Wanstead House—a magnificent Palladian residence designed by Colen Campbell—was among the first in England to have its existing formal gardens renovated (c. 1725–71) in the Romantic, naturalistic mode that became known as the English style. Thousands of shrubs and trees were added to the park, along with architectural accents (such as a boathouse-grotto on the man-made lake and an ornamental temple that also functioned as a poultry house and keeper’s lodge).[5] Vaughan would include similar garden features in the landscape projects he later oversaw in Philadelphia.

Within months of the conclusion of the American Revolutionary War, Vaughan relocated his family to Philadelphia where, in December 1783, he met and initiated an enduring friendship with his hero, George Washington, to whom he was introduced by Benjamin Rush.[6] Vaughan took particular interest in the architecture, grounds, and interior decoration of Mount Vernon, advising Washington on fashionable English trends, offering to supply skilled workmen, and sending gifts such as an English fireplace mantel carved with rustic subjects.[7] Vaughan also became a driving force within Philadelphia’s intellectual, civic, and scientific communities. By January 1784 he had engaged a workman to implement his ambitious plan to landscape the State House Yard (an open green at the center of State House Square) as a public garden.[8] He joined the American Philosophical Society in the same month, and assumed responsibility for planning Philosophical Hall, the Society’s new headquarters on the grounds of the State House Yard. In a letter of March 8, 1784, Vaughan assured the Society’s founder, Benjamin Franklin, that the building would “be sufficiently ornamental not to interfere materially with the views of making a publick walk.”[9] Vaughan initially envisioned the State House Yard as a national arboretum, with “a specimen of every sort of [tree and shrub] in America that will grow in this state.”[10] Vaughan purchased many of these specimens from John and William Bartram, and also consulted the Bartrams’ cousin Humphry Marshall. His high regard for Marshall’s efforts to document the “original botanical information of the New World,” led Vaughan in May 1785 to solicit support from the American Philosophical Society (of which he was now a vice-president) and the Philadelphia Society for the Promotion of Agriculture (which he had co-founded a few months earlier). When those efforts failed, he personally supervised and financed publication of Marshall’s manuscript, Arbustrum [sic] Americanum (1785), and even translated Latin terms for the English language index.[11]

Although Vaughan ultimately scaled back his encyclopedic plan for landscaping the State House Yard, he nevertheless assembled a great number and variety of specimens, which he laid out in accordance with the naturalistic conventions of the English style. In addition to receiving accolades for his good taste and generosity in developing the State House Yard, Vaughan was praised for his signal contributions to the American Philosophical Society. In a letter of August 2, 1786, Benjamin Rush observed, “He [Vaughan] has been the principal cause of the resurrection of our Philosophical Society. He has even done more, he has laid the foundation of a philosophical hall which will preserve his name and the name of his family among us for many, many years to come.”[12] Less well known was Vaughan’s responsibility for the fashionable pleasure garden recently opened at Gray’s Tavern on the Schuylkill River. With the aid of an English gardener and a team of laborers, Vaughan had transformed the steep, wooded grounds into a romantic park known as Gray’s Garden. A maze of paths meandered through informal plantings of flowers and shrubs, and featured picturesque views of fanciful garden structures such as grottoes, Chinese bridges, and a rustic hermitage that functioned as a bathhouse.[13]

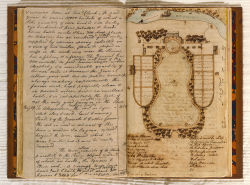

Despite his many occupations in Philadelphia, Vaughan traveled frequently to Boston and visited other regions of the United States. In July 1786 he and Manasseh Cutler began preparations for a trip to the White Mountains, where they intended to study native flora, fauna, and minerals (Vaughan’s pet subject), aided by scientific instruments that Vaughan had imported from Europe.[14] In 1787 Vaughan hosted two dinners for George Washington while the president was in Philadelphia for the Federal Convention, and then set off on a 1400-mile journey to Mount Vernon. During his trip, Vaughan kept a journal in which he detailed the sites and natural phenomena he encountered while traveling through Pittsburgh (celebrating the 4th of July at Fort Pitt), Berkeley Springs, Williamsburg, and other towns.[15] At Mount Vernon Vaughan made notes on the mansion and grounds and completed a sketch [Fig. 2], from which he later produced two more detailed versions, one of which he sent as a gift to Washington.[16]

In 1790 Vaughan took his final leave of America and returned to England. Just prior to his departure, he formally requested that William Bartram—rather than an English gardener—be entrusted with maintaining the shrubs and trees at the State House Yard, asserting: “He is fully competent to the business, which I conceive not to be the case of the English Gardiner proposed, who not being acquainted with the productions of this Country & who hath neither ability to judge or means to procure the variety necessary to supply those destroyed or dead.”[17] From the other side of the Atlantic, Vaughan continued to exchange scientific information and specimens with Cutler, Washington, and other American friends. He also supervised the development of property inherited from his father-in-law, Benjamin Hallowell, in the town of Hallowell, Maine. As early as 1784, he had sought to establish a Unitarian community there and he continued to promote the spiritual, agricultural, and mercantile growth of the town through family members who became residents—most notably his son Benjamin, who developed a noted garden while advancing the pioneering horticultural work that had become a family tradition.[18]

—Robyn Asleson

Texts

- Vaughan, Samuel, May 28, 1785, in a letter to Humphry Marshall[19]

- “As it is my wish to plant in the State house square specimens of every tree & shrub that grow in the several states on this Continent that will thrive here, I have enclosed a sketch of such others as I have been able to procure since the 7th of last month, with a list of such others as have occurred to me hitherto, but as I am unacquainted with the vast variety remaining & that you have turned your thoughts in that line, I have to request, & shall be much obliged to you for a list of such as occur to you, with directions in what state or place they are to be had; that I may lay out to procure them to plant in the fall.”

- Hunter, Robert, October, 1785, describing the State House Yard in Philadelphia, PA (quoted in 1943: 169)[20]

- “The state-house is infinitely beyond anything I have either seen in New York or Boston, and the walk before it does infinite honor to Mr. Vaughan’s taste and ingenuity in laying it out.”

- Cutler, Manasseh, July 1787, describing the State House Yard in Philadelphia, PA (quoted in 1888: 1:262–63)[21]

- “As you enter the Mall through the State House, which is the only avenue to it, it appears to be nothing more than a large inner Court-yard to the State House, ornamented with trees and walks. But here is a fine display of rural fancy and elegance. It was so lately laid out in its present form that it has not assumed that air of grandeur which time will give it. The trees are yet small, but most judiciously arranged. The artificial mounds of earth, and depressions, and small groves in the squares have a most delightful effect. The numerous walks are well graveled and rolled hard ; they are all in a serpentine direction, which heightens the beauty, and affords constant variety. That painful sameness, commonly to be met with in garden-alleys, and others works of this kind, is happily avoided here, for there are no two parts of the Mall that are alike. Hogarth’s 'Line of Beauty' is here completely verified. The public are indebted to the fertile fancy and taste of Mr. Sam'l Vaughan, Esq., for the elegance of this plan. It was laid out and executed under his direction about three years ago. The Mall is at present nearly surrounded with buildings, which stand near to the board fence that incloses it, and the parts now vacant will, in a short time, be filled up. On one part the Philosophical Society are erecting a large building for holding their meetings and depositing their Library and Cabinet. This building is begun, and, on another part, a County Court-house is now going up. But, after all the beauty and elegance of this public walk, there is one circumstance that must forever be disgusting and must greatly diminish the pleasure and amusement which these walks would otherwise afford. At the foot of the Mall, and opposite to the Court-house, is the Prison, fronting directly to the Mall.

- Vaughan, Samuel, July 1787, describing Mount Vernon, plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (quoted in 1961: 273)[22]

- “Before the front of the house. . . there are lawns, surrounded with gravel walks 19 feet wide. with trees on each side the larger, for shade. outside the walks trees & shrubberies. Parralel [sic] to each exterior side a Kitchen Gardens. with a stately hot house on one side. the exteriour side of the garden inclosed with a brick wall.”

- Anonymous, July 1787, “Account of the State-House of Pennsylvania” (Columbian Magazine 1: 513)[23]

- “The state-house yard has been highly improved by the exertions of Mr. Samuel Vaughan, and affords two gravel walks, shaded with trees, a pleasant lawn, and several beds of shrubs and flowers.”

- Anonymous [“B.”], January 1790, “Explanation of the Plate, exhibiting a View of several Public Buildings in the City of Philadelphia” (Columbian Magazine 4: 25–26)[24]

- “The State-house square... is inclosed [sic], on three sides, by a brick wall.... This area has, of late, been judiciously improved, under the direction of Samuel Vaughan, Esq. It consists of a beautiful lawn, interspersed with little knobs or tufts of flowering shrubs, and clumps of trees, well disposed. Through the middle of the gardens, runs a spacious gravel-walk lined with double rows of thriving elms, and communicating with serpentine walks which encompass the whole area. These surrounding walks are not uniformly on a level with the lawn; the margin of which, being in some parts a little higher, forms a bank, which, in fine weather, affords pleasant seats. When the trees attain to a larger size, it will be proper to place a few benches under them, in different situations, for the accommodation of persons frequenting the walks.

- “These gardens will soon, if properly attended to, be in a condition to admit of our citizens indulging themselves, agreeably, in the salutary exercise of walking. The grounds, though not so extensive as might be wished, are sufficiently large to accommodate very considerable numbers: the objects within view are pleasing; and the situation is open and healthy. If the ladies, in particular, would occasionally recreate themselves with a few turns in these walks, they would find the practice attended with real advantages.”

Images

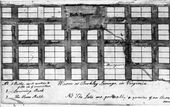

Samuel Vaughan, Sketch plan of Mount Vernon, June–September 1787.

Samuel Vaughan, Plan of Mount Vernon, 1787.

Samuel Vaughan, Plan of Bath [Berkeley Springs], Virginia, 1787, from the diary of Samuel Vaughan, June–September 1787.

Samuel Vaughan, “Warm or Berkeley Springs in Virginia,” 1787, from the diary of Samuel Vaughan, June–September 1787.

Other Resources

The Cultural Landscape Foundation

The Massachusetts Historical Society

Vaughan family papers, Massachusetts Historical Society

Notes

- ↑ Alan Taylor, Liberty Men and Great Proprietors: The Revolutionary Settlement on the Maine Frontier, 1760–1820 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1990), 34, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Emma Huntington Nason, Old Hallowell on the Kennebec (Augusta, ME: Press of Burleigh & Flynt, 1909), 74–75, view on Zotero; Biographical Sketches of Representative Citizens of the State of Maine, American Series of Popular Biographies—Maine Edition (Boston: New England Historical Publishing Company, 1903), 167, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Verner W. Crane, “The Club of Honest Whigs: Friends of Science and Liberty,” William and Mary Quarterly, 23 (April 1966): 220–21, 228, view on Zotero; Samuel Vaughan, “Samuel Vaughan’s Journal, or ‘Minutes Made by S.V., from Stage to Stage, on a Tour to Fort Pitt.’ Part I,” ed. Edward G. Williams, Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine 44 (March 1961): 52–53, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Josiah Quincy, Memoir of the Life of Josiah Quincy, Junior, of Massachusetts Bay: 1744–1775, ed. Eliza Susan Quincy (Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1875), 204, 214, 242, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Sally Jeffery, “The Gardens of Wanstead,” in Proceedings of a Study Day held at the Temple, Wanstead Park, Greater London, September 25, 1999, ed. Katherine Myers (London: London Historic Parks and Gardens Trust, 2003), 24–36, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anna Coxe Toogood, Independence Square, Volume 1: Historical Narrative (Independence Historical National Park: National Park Service, 2004), 74, view on Zotero; Craig Compton Murray, “Benjamin Vaughan (1751–1835): The Life of an Anglo-American Intellectual” (PhD diss., Columbia University, 1989), 200, view on Zotero; Sarah P. Stetson, “The Philadelphia Sojourn of Samuel Vaughan,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 73 (1949): 461, view on Zotero.

- ↑ George Washington to Samuel Vaughan, June 20, 1784, The Papers of George Washington, Confederation Series, ed. William Wright Abbot and Dorothy Twohig, 6 vols. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1992), 1:466, view on Zotero; see also 1:45–46, 273–74; 2:326; 4:384; Robert F. Dalzell and Lee Baldwin Dalzell, George Washington’s Mount Vernon: At Home in Revolutionary America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), 112–15, view on Zotero; Joseph Manca, George Washington’s Eye: Landscape, Architecture, and Design at Mount Vernon (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 9, 22, 25, 171, 173–74, 194, 198, view o Zotero; “Samuel Vaughan and George Washington,” Mount Vernon website.

- ↑ Toogood 2004, 72, 82–83, view on Zotero; John C. Greene, “The Development of Mineralogy in Philadelphia, 1780–1820,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 113 (August 1969): 283–95, view on Zotero; Stetson 1949, 464–65, 469, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Vaughan quoted in Toogood 2004, 73, view on Zotero; see also 82–83; Greene 1969, 290, view on Zotero; Stetson 1949, 464–65, 469, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Quotation from Samuel Vaughan to Humphry Marshall, May 14, 1785, Series X, Manuscripts, Box 10/4, file “Humphry Marshall Papers,” USDA History Collection 7, Special Collections, National Agricultural Library, view on Zotero. See also Toogood 2004, 86, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Quotation from Samuel Vaughan to Humphry Marshall, April 30, 1785, Series X, Manuscripts, Box 10/4, file “Humphry Marshall Papers,” USDA History Collection, Special Collections, National Agricultural Library, view on Zotero. See also Toogood 2004, 82, view on Zotero; Joseph Ewan, “Philadelphia Heritage: Plants and People,” in America’s Garden Legacy: A Taste for Pleasure, ed. George H. M. Lawrence (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1978), 28 view on Zotero; Stetson, 1949, 469–470, view on Zotero.

- ↑ William E. Lingelbach, “Philosophical Hall: The Home of the American Philosophical Society,” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 43 (1953): 49, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Toogood 2004, 83, view on Zotero; Stetson 1949, 467–68, view on Zotero; Manasseh Cutler, Life, Journals and Correspondence of Rev. Manasseh Cutler, LL.D., ed. William Parker Cutler and Julia Perkin Cutler, 2 vols. (Cincinnati: Robert Clarke & Co., 1888), 1: 275–77, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Cutler 1888, 2:247, 271, 281, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Williams, March 1961, 53, 56–65, view on Zotero; Samuel Vaughan, “Samuel Vaughan’s Journal, or ‘Minutes Made by S.V., from Stage to Stage, on a Tour to Fort Pitt.’ Part II, From Carlisle to Pittsburgh,” ed. Edward G. Williams, Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine 44 (June 1961): 160–73, view on Zotero; Samuel Vaughan, “Samuel Vaughan’s Journal, or ‘Minutes Made by S.V., from Stage to Stage, on a Tour to Fort Pitt.’ Part III. From Pittsburgh to Fort Cumberland Thence to Mount Vernon,” ed. Edward G. Williams, Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine 44 (September 1961): 261–85, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Williams, June 1961, 273–74, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Stetson 1949, 80, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Taylor 1990, 34–37, view on Zotero; Murray 1989, 204, view on Zotero; Nason 1909, 50–51, view on Zotero; George Willis Cooke, Unitarianism in America: A History of Its Origin and Development (Boston: American Unitarian Association, 1902), 77, view on Zotero; John H. Sheppard, Reminiscences of the Vaughan Family, and More Particularly of Benjamin Vaughan, LL.D. (Boston: David Clapp & Son, 1865), 5–6, 12–15, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Series X, Manuscripts, Box 10/4, file “Humphry Marshall Papers,” Special Collections, National Agricultural Library, 1785), USDA History Collection, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Robert Hunter, Quebec to Carolina in 1785–1786: Being the Travel Diary and Observations of Robert Hunter, Jr., a Young Merchant of London, ed. Louis B. Wright and Marion Tinling (San Marino, CA: Huntington Library, 1943), 169, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Cutler 1888, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Vaughan 1961, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, “Account of the State-House of Pennsylvania,” Columbian Magazine, 1, no. 11 (July 1787): 513, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous [“B.”], “Explanation of the Plate, exhibiting a View of several Public Buildings in the City of Philadelphia,” Columbian Magazine 4, no. 1 (January 1790): 25–26, view on Zotero.