Bath/Bathhouse

(Bath-house, Bathing house)

History

The bath and bathhouse in America had many forms, including private versions attached to houses or separately constructed in a garden, and public baths at resorts, in public gardens, and at the seaside. The term “bath” referred both to the structure covering the water and to the watering receptacle or pool itself. The structures were sometimes called bathhouses or bathing houses. Baths at natural sources of mineral waters were also referred to as spas and springs.

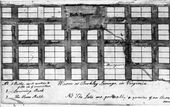

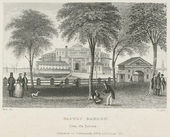

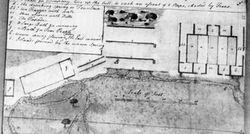

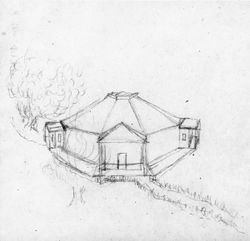

Although garden treatise literature contains few references to garden baths, other evidence indicates that the bathhouse held a prominent position in American ornamental landscapes. Baths were situated in public gardens, such as a public bath and garden in Norfolk, Virginia, or Bathsheba’s Bath and Bower in Philadelphia, and in many private gardens, such as John Donnell’s Willow Brook in Baltimore and Charles Willson Peale's Belfield in Philadelphia. Baths at private estates might be simple, as suggested by the note in the South Carolina Gazette in 1733, of “frames, Planks, &c. to be fix’d in and about a Spring. . . intended for a Cold Bath.” They also could be quite substantial, as was Charles Carroll of Carrollton’s stone-lined bath, which he ordered in 1778 to measure ten by eight feet with a depth of four-and-a-half feet. Few detailed descriptions of the architecture of these bathhouses survive, however. At Monte Video in Connecticut, the bathhouse was described merely as Gothic. More is known about the architecture of public baths, where the structures were larger and often quite elaborate. Many textual descriptions and images of baths survive because they were considered civic amenities, such as the bath at Castle Garden in New York [Fig. 1]. Samuel Vaughan's plan of 1787 for the town of Bath included “baths [at a] for company 5 by 18 feet that fills in 5 minutes & emties [sic] in four,” dressing rooms [b], two piazzas with seats [bb], a large bath for swimming [f], and a separate “Bath for Poor People [g]” [Fig. 2]. Sophie Madeleine du Pont in 1837 described and sketched a bathhouse at Warm Springs (Berkeley Springs), Virginia (later West Virginia), with a thirty-foot octagonal masonry basin and four separate bathing rooms [Fig. 3].

Mineral springs were visited as early as 1669 when Massachusetts colonists took the waters at Lynn Red Spring, but it was not until the end of the French and Indian War that springs began to be developed widely as commercial establishments.[1] A bath at Stafford Springs in Connecticut opened in 1765 and became, in the words of Samuel Peters, “where the sick and rich resort to prolong life, and acquire the polite accomplishments.”[2] In addition to bathing, spas, such as Yellow Sulphur Springs, near Philadelphia, often included a variety of entertainments such as dining, dancing, and overnight lodging.[3] Bathing, as a general practice, was argued to have healthful effects. J. B. Bordley wrote in 1798 that “[e]very family in this fine climate ought to have its bath. . . Bathing moistens, soaks, washes, supples and refreshes the whole body.” At the age of 95, Charles Carroll of Carrollton credited his longevity to daily cold baths. When bathed in and imbibed, mineral waters rich in sulfur and iron were particularly renowned for their curative properties for ailments such as rheumatism, cholera, malaria, hysteria, gout, and digestive disorders. Du Pont, seeking relief from a back and knee ailment, took the waters of Warm Springs, and she described vividly the sulfur-rich water’s “odour of half spoiled eggs.”

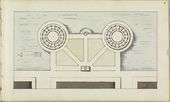

As their popularity grew, accommodations and other facilities were built at many of the springs to cater to the travelers seeking rest and refreshment. These resorts often included elaborate gardens. In 1776, the Virginia Assembly laid out the town of Bath around a spring that had been owned by Lord Fairfax. Lots sold at 25 guineas each, and Bath included a theater, inns, and places to ride and play billiards. Charles Varlé’s landscape design for the town in 1809 [Fig. 4] included a reservoir or fountain “covered with a vine treliage in a form of a dome or copula,” a jet d’eau, a bowling green, and two labyrinths “contrived so as to be different in their issues and windings.” The town became a fashionable resort; visitors included Baron and Baroness de Riedesel and Mrs. Charles Carroll of Carrollton.[4]

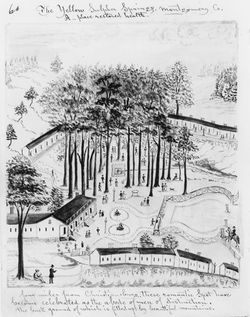

The Bath resort community declined in popularity with the rise of the other Virginia springs in the Allegheny highlands described by Thomas Jefferson as “medicinal springs.” These springs became part of a social tour that lasted from July through mid-September. The tour generally started at Warm Springs, and continued on to Hot Springs, White Sulphur Springs, Sweet Springs, Salt Sulphur Springs, and Red Sulphur Springs.[5] Lewis Miller’s sketch of Yellow Sulphur Springs illustrates accommodations, walks, benches, lighting, and other features for the recreation of the bathers [Fig. 5]. Historian Carl Bridenbaugh credits these resorts, at least in colonial times, with “promoting colonial union and. . . nourishing nascent Americanism.” He argues that, in addition to the springs’ appeal as salubrious escapes from humidity, heat, and noise, they offered the “most significant intercolonial meeting places. . . [and] provided a powerful solvent of provincialism.”[6] As some of the most elaborate landscape designs of the period suggest, resorts may also have done much to disseminate the fashion for baths and bathhouses in residential gardens as well.

—Elizabeth Kryder-Reid

Texts

Usage

- Anonymous, July 28, 1733, describing a plantation for sale in Charleston, SC (South Carolina Gazette)

- “A Plantation about two Miles above Goose-Creek Bridge. . . [had] a Spring within 3 Stones throw of the House, intended for a Cold Bath.”

- Anonymous, February 6, 1746, describing in the Boston Weekly News-Letter the property of John Welch, Boston, MA (quoted in Benes 1996: 53)[7]

- “TO BE LETT, (exclusive of the Bath-House) The Bath-Garden, at the Westerly Part of the Town, which has for many Years been improv’d as a public Garden, and contains a Variety of the best Fruit-Trees, a great Quantity of Currant and Gooseberry Bushes, some of the best Grape Vines, a handsome Summer-House, Glasses for Hot-Beds, &c Enquire of John Welch, and know further. N.B. The Cold Bath is in good Order for Use and has been found beneficial to several that have used it, even this Winter-Season: Price 40 Shillings a Year or 5 Shillings each single Time, old Tenor.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, 1771, describing Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, VA (1944: 26)[8]

- “. . . a few feet below the spring level the ground 40 or 50 f. sq. let the water fall from the spring in the upper level over a terrace in the form of a cascade. then conduct it along the foot of the terrace to the Western side of the level, where it may fall into a cistern under a temple, from which it may go off by the western border till it falls over another terrace at the Northern or lower side. let the temple be raised 2. f. for the first floor of stone. under this is the cistern, which may be a bath or anything else. the 1st story arches on three sides; the back or western side being close because the hill there comes down, and also to carry up stairs on the outside. the 2d story to have a door on one side, a spacious window in each of the other sides, the rooms each 8. f. cube; with a small table and a couple of chairs. the roof may be Chinese, Grecian, or in the taste of the Lantern of Demosthenes at Athens.”

- Quincy, Josiah, May 3, 1773, describing the country seat of John Dickensen, near Philadelphia, PA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “This worthy and arch-politician. . . here enjoys otium cum dignitate as much as any man. Take into consideration the antique look of his house, his gardens, green-house, bathing-house, grotto, study, fish-pond, fields, meadows, vista, through which is distant prospect of Delaware River.”

- Carroll (of Carrollton), Charles, May 24, 1778, in a letter to his father, Charles Carroll (of Annapolis), describing the Carroll Garden, Annapolis, MD (Maryland Historical Society, A. E. Carroll Papers, MS 206, no. 479)

- “If Joe has finished all the Jobbs at Annapolis, I wish you would set him about preparing stones to line a cold bath; the stones already raised at the soap stone quarry would be sufficient for this purpose, as the bath need not be in the clear more than 10 feet long & 8 broad & 4 feet 6 inches deep. When I return I will direct where it shall be dug.”

- Peters, Samuel, 1782, describing Stafford Springs, CT (quoted in Bridenbaugh 1946: 153)[9]

- “. . . the New England Bath, where the sick and rich resort to prolong life and acquire the polite accomplishments.”

- Anonymous, April 28, 1786, describing a new bathing house in Charleston, SC, in the Charleston Morning Post, and Daily Advertiser (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “A Bathing House BEING about to be erected at the Retreat, those Gentlemen who wish to become subscribers, are requested to leave their name and the Needful at the said place, as speedily as possible. . . Many attempts have been made to establish a BATHING HOUSE, but none of them have succeeded, and when it is recollected that in this climate, such an Establishment would be in the highest degree beneficial, it seems truly astonishing. . . in a considerable measure by this reflection, the Subscriber now issues Proposals for the erection of a permanent and elegant BATHING HOUSE.”

- Peale, Charles Willson, June 1788, describing Annapolis, MD (Miller et al., eds., 1983: 1:498)[10]

- “. . . being invited to dine with the fish Club, I took my Gun for further Amusement; the club had a marqui fixed opposite the Cool Spring (bath House) on the other side of the creek. They have skittle Ground and qu[o]ites to amuse themselves.”

- Chapman, Thomas, 1795–96, describing a plantation near Harrodsburg, KY (quoted in Schwaab 1973: 28)[11]

- “Colonel Nicholas’s Plantation is in a higher State of Improvement than any other in the State of Kentucky. Exclusive of a good Framed Commodious House, a famous Spring Dairey [sic], where Milk can be kept cool in the hotest [sic] Day of Summer, there is a large Barn, Stable, and out Offices, and a large Grist Mill, supplied with Water from the same Spring wch [sic] passes through the Spring House. There is also a bathing House connected with the Dairey [sic], and an Apple Orchard of 400 Young thriving Trees.”

- Bentley, William, July 12, 1797, describing Salem, MA (1962: 2:228)[12]

- “12. Plenty of Mackerel in the market at 6 cents pr. lb. A Bath house is begun on the back of our land which is to extend 64 feet upon B., & to have eight apartments. The success is doubtful for it is said such a thing much talked of was not much used when gotten.”

- Dwight, Timothy, 1799, describing a lunatic asylum in New York, NY (1822: 3:454)[13]

- “Among its conveniences are an excellent garden, fruit trees, walks, a large ice-house, bathing-house, and stables.”

- Anonymous, April 18, 1800, describing in the Federal Gazette Willow Brook, seat of John Donnell, Baltimore, MD (quoted in Sarudy 1989: 137)[14]

- “In the garden is a neat wooden house, with a twelve foot passage, and five rooms: a gardener’s house, a fish pond well stocked with fish, and an elegant bath with two dressing springs of fine soft water.”

- Bentley, William, 1800 and 1802, describing Salem, MA (1962: 2:339, 437)[12]

- “31. [May 1800] The weather begins to feel like Summer. I bathed in the river this evening, & the Bath House was opened for the first time. . .

- “July 1 [1802] walked down Seargeant’s new wharf, which is now the best in the Town. Near it, eastward, is a bathing house for salt water, lately erected for females, but little used.”

- Latrobe, Benjamin Henry, March 26, 1805, describing a design for a house in Philadelphia, PA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “From the kitchen a door leads to the Back stairs, which communicate immediately with the Dining room, and the Lady’s apartment above stairs. At the foot of these stairs is a small room, which can be well adapted to the purpose of a bath, or a store room.”

- Caldwell, John Edwards, 1808, describing Hot Springs, VA (1951: 31)[15]

- “The Hot Springs are in Bath county, 36 miles from the Sweet Springs. Here are three baths, one of vital heat, or 96 degrees of Farenheit’s thermometer: one of 104°, and it is said that the hottest is 112°, and sufficiently hot to boil an egg. The patient, on coming out of the two latter, is wrapped up in blankets, and lies stewing in the sweating room adjoining the bath, until the perspiration has freely spent itself from every pore of the body.”

- Peale, Charles Willson, July 29, 1810, in a letter to his son, Rembrandt Peale, describing Belfield, estate of Charles Willson Peale, Germantown, PA (Miller et al., eds., 1991: 3:55)[16]

- “The Barn and one of the Barracks on the West, the Coach-House near the Center, Spring-house on the East side and the Bath House below it. There is 4 large Popplers (Tulip Tree) which crosses the Road, and the Lumbardy Poppler a row of them on your right hand. Just above the bath-House is a small fish pond with about 200 Catfish which I brought from the falls of Schulkill.”

- Anonymous, April 24, 1813, describing Norfolk, VA (Norfolk Gazette and Publick Ledger)

- “PUBLIC BATHS AND GARDEN, OPPOSITE THE THEATRE.

- “The subscriber, ever grateful to his friends and the public in general for their past favors, takes this method of informing them that his Baths will be opened every day (when fair) from 6 A.M. to 9 P.M. He flatters himself that by the neatness and promptitude which he will exert himself in serving those who will favor him with their custom, to merit the public patronage. The price for Baths, as heretofore, three for one dollar; 37 1-2 cents for a single one.”

- Anonymous, September 18, 1813, describing in the City Gazette and Commercial Daily Advertiser a proposed bathhouse in Charleston, SC (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “A splendid Establishment. The subscriber has it in contemplation to erect at the East Bay in this city a CIRCULAR FLOATING BATHING HOUSE, on a new, highly approved, extensive and elegant plan—to go into operation in the season of 1814. It will be 250 feet in circumference, built of the best materials, and in the most substantial manner, forming a beautiful structure, which (besides increasing the resources of health and pleasure) will be greatly ornamental to the city. It will contain FORTY capacitus private bathing rooms, lighted by VENETIAN windows: a large SWIMMING bath in the centre, of about 160 feet circumference: FORTY dressing CLOSETS attached to the swimming bath: two spacious SITTING rooms, one for the accommodation of LADIES, and the other for GENTLEMEN.”

- Anonymous, March 29, 1815, describing a sale in Richmond, VA (Daily Compiler)

- “MARBLE MANTLES FOR SALE. A number of elegant marble Mantles, from Philadelphia, at the house formerly occupied as a Bathing house, on the cross street leading to Mayo’s Bridge.”

- Lambert, John, 1816, describing Charleston, SC (1816: 2:139–40)[17]

- “The garden dignified by the name Vauxhall is also under the direction of Mr. Placide. It is situated in Broad-street, a short distance from the theatre, surrounded by a brick wall, but possesses no decoration worthy of notice. It is not to be compared even with the common tea-gardens in the vicinity of London. There are some warm and cold baths on one side for the accomodation of the inhabitants. . . The heavy dews and vapours which arise from the swamps and marshes in its neighbourhood, after a hot day, are highly injurious to the constitution, particularly while it is inflamed by the wine and spirituous liquors which are drunk in the garden. It is, also, the period of the sickly season when the garden is open for public amusement, and the death of many performers and visitors may be ascribed to the entertainments given at that place.”

- Paulding, James Kirke, 1816, describing Warm Springs (Berkeley Springs), VA (later WV) (1817: 1:167, 169; 2:235)[18]

- “[Vol. 1]. The bath here is the most luxurious of any in the world; its temperature about that of the body, its purity almost equal to that of the circumambient air: and the fixed air plays against the skin, in a manner that tickles the fancy wonderfully. . .

- “The bath is about thirty feet in diameter, forming an octagon, walled two or three feet above the water’s edge; the bottom covered with pebbles, and the water so pure, that if it were only deeper, a man’s head would turn in looking down into it. . .

- “[Vol. 2]. There is a pavilion built over the spring, which is used for drinking, and two bathhouses—one for either sex. The spring which supplies the ladies’ bath is one of the finest I have ever seen. It bursts from a fissure in the rock in the form of a cone, much larger than the crown of a hat, and, together with the others, forms a fine stream, in some places six or eight yards wide.”

- Warden, David Bailie, 1816, describing Bladensburg, MD (1816: 160)[19]

- “The mineral spring is pleasantly situated on the side of the stream, near a fine clump of trees at the entrance of the village. It would not require much expense to make this an agreeable watering place. . . By means of a thermometer, which Mr. Diggs politely procured, we found the temperature of the water to be 55 1/2°. Some years ago, a public bath was constructed near the spring, but the temperature was found to be disagreeably cold, and it was entirely abandoned.”

- Deford, William, May 5, 1819, describing in the American Beacon and Norfolk & Portsmouth Daily Advertiser Wigwam Gardens in Norfolk, VA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “Bathing imparts new vigour and elasticity to the system—It is the grand restorative of nature. Public Bathing house. THE Subscriber having, at a considerable expense, and with much personal labour, put his BATHS in such order as to render them worthy of the public attention, hopes to receive that remuneration which h[i]s efforts merit, and which, he feels assured, a prudent regard to the preservation of their health, will ensure to him, from his fellow citizens.

- “In his arrangements for the Season, which commenced on the 1st ins. he flatters himself, that he has neglected nothing which may be necessary to recommend his Baths for cleanliness, convenience, privacy, or attendance, and Ladies and Gentlemen can be accommodated at any hour, with Hot, Cold, or Tepid Baths, as may be best adapted to their health or taste.”

- Anonymous, March 22, 1820, describing in the City Gazette and Commercial Daily Advertiser a salt water bathing house proposal in Charleston, SC (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “SALT WATER BATHING HOUSE. Many attempts have been made to establish a BATHING HOUSE, but none of them have succeeded, and when it is recollected that in this climate, such an Establishment would be in the highest degree beneficial, it seems truly astonishing.—in a considerable measure by this reflection, the Subscriber now issues Proposals for the erection of a permanent and elegant BATHING HOUSE. It depends upon the public whether his plans are carried into execution or not. Should a sufficient number of Subscribers be obtained, the work will be completed by the latter end of May: but it is not necessary that two hundred be obtained by the middle of April.

- “The following is a brief sketch of the plan and situation: The Building will be erected at the East end of Laurens street, a low water mark: the Foundation to be made of Palmetto Logs, 46 feet square, containing 14 private Baths, with a Bath in the centre of 20 feet diameter: the bottom of the baths to be floored: over the Dressing Room will be a Platform and Railing, over which there will be a Roof. There will be a Bridge leading form Laurens street to the Bathing House.

- “Those Gentlemen who feel disposed to encourage the undertaking are requested to subscribe immediately.”

- Silliman, Martha Trumbull, September 1, 1821, describing Monte Video, property of Daniel Wadsworth, Avon, CT (quoted in Saunders and Raye 1981: 20)[20]

- “The place is a great deal handsomer than I expected. The buildings are all Gothic. First there is Uncles beautiful house; 2d the tower, 3d the cottage & the barns 4th the boat house & 5th the bathing house 6th a grape house 7th an ice house & 8th the bee house & a Gothic gate.”

- “This is a very remarkable fountain. Unlike most mineral waters, it issues from a high hill; the water boils up in a space of ten feet wide, by three and a half deep. . . the water discharged amounts to eighteen barrels in a minute, and not only supplies the baths very copiously, simply by running down hill to them.”

- Peale, Charles Willson, c. 1825, describing New York, NY (Miller et al., eds., 2000: 5:247–48)[22]

- “Peale went to a bathing house on the north river, this building has a private as well as public bathing places, for men or women. The cost of public bathing is 12 1/2 Cts. and 25 Cents for private bathing. . .

- “The public Bath is extended wings on each side about 40 feet into the river on which there are a range of boxes to dress and undress, these have stairs with ropes to decend into the water on the 3 sides and at the end next the river is a sunken vessel of an oblong square, and the debth of the water therein is about 4 feet, for the accomdation of those who cannot swim. In the private baths they have the same kind of vessels which rise and fall with the tide. You are furnished with a towel and an oil cap for the head. They have warm baths for those who want them. The[re] is another bathing house on the same river, which at present is not in order except for the accomodation of women.

- “If there were also Bathing houses on the east river, and it was the custom generally for the Inhabitants to make frequent use, especially during the hot seasons, it would contribute much to ward off those dreadful fevers which too oftain afflict large Cities.”

- du Pont, Sophie Madeleine, July 21, 1837, describing Warm Springs (Berkeley Springs), VA (later WV) (quoted in Low and Hinsley 1987: 173, 179)[23]

- “Warm Springs. . . The most abundant of these gushes from the earth in the middle of a large octagonal basin of mason work covered with a wooden building having an opening at the top, & four neat & comfortable rooms on as many sides for the accommodation of bathing. This bath is thirty eight feet in diameter; & the temperature of water 96 degrees—It is one of the most curious & beautiful objects I have seen, the water is pure & translucent to an almost dazzling degree, & rises in ceaseless flow, accompanied by showers of bright gleaming air bubbles. . .

- “There are several other springs of the same kind in the meadow—round one a platform is built with benches, under shady trees, for those who drink the water, which notwithstanding its odour of half spoiled eggs & its warmth, is not very nauseous to the taste—Another bath house contains four small baths, into one of which a spout is arranged for the benefit of those who are recommended to take douches. I have tried this at Dr Horner’s request & think it of service to me, as well as the bathing.” [Fig. 6]

- Alcott, William A., August 1838, “Embellishment and Improvement of Towns and Villages” (American Annals of Education 8: 343)[24]

- “In all our larger cities and towns there should be public baths, and custom should require their daily use by those who have not the means of private ones. And if we do not recommend public bathing houses to every town and village of New England, of every size, it is because we do humbly hope our citizens will provide themselves with conveniences of the kind at their own expense, when they can be made to feel their importance.”

- Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), October 1850, “Notes on Gardens and Nurseries,” describing a residence in Cambridge, MA (Magazine of Horticulture 16: 462)[25]

- “The sailing pond, with the exception of the walks around the border, and the planting of a few trees on the island in the centre, have been completed since last year, and a fine boat-house, to combine a bathing-house, &c., was now just being finished.”

- Watson, John Fanning, 1857, describing Bathsheba’s Bath and Bower, Philadelphia, PA (1857: 1:411)[26]

- “I had long heard traditional facts concerning the rural beauty and charming scenes of Bathsheba's bath and bower, as told among the earliest recollections of the aged. They had heard their parents talk of going out over the Second street bridge into the country about the Society hill, and there making their tea—regale at the above—named spring.”

Citations

- Chambers, Ephraim, 1741, Cyclopaedia (1741: 1:n.p.)[27]

- “BATH, BALNEUM, a convenient receptacle of water for persons to wash, or plunge in, either for health or pleasure. See WATER. Baths are either natural or artificial. Natural, again, are either hot or cold. . .

- “BATHS, BALNEA, in architecture, denote large pompous buildings among the ancients, erected for the sake of bathing.

- “Baths made a part of the ancient gymnasia.”

- Bordley, J. B., July 1798, Country Habitations (1798: 11)[28]

- “Thus from water thrown up, every house might have family baths; the most important of all building—improvements for the health and comfort of families, that can be adopted in our climate especially. You now rise from bed and wash face and hands—your tip ends. Why not rise and plunge into your wash-bason—a bath adjacent to your bed-chamber? instead of using a gallon vessel of water, only for hands and face! Every family in this fine climate ought to have its bath; and when there are servants, proper bathing places should be provided for them.

- “Bathing moistens, soaks, washes, supples and refreshes the whole body. When the water is tepid, bathing is always safe, cleaning and refreshing; when cold, or made more than blood warm, it is wholesome or not according to the state of health; but is very beneficial in many cases, when well advised to use the one or the other, according to the state of health.”

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828: 1:n.p.)[29]

- “B`ATH, n. [Sax. baeth, batho, a bath; bathian, to bathe; W. badh, or baz; D. G. Sw. Dan. bad, a bath; Ir. bath, the sea; Old Phrygian bedu, water. Qu. W. bozi, to immerse.]

- “1. A place for bathing; a convenient vat or receptacle of water for persons to plunge or wash their bodies in. Baths are warm or tepid, hot or cold, more generally called warm and cold. They are also natural or artificial. Natural baths are those which consist of spring water, either hot or cold, which is often impregnated with iron, and called chalybeate, or with sulphur, carbonic acid, and other mineral qualities. These waters are often very efficacious in scorbutic, bilious, dyspeptic and other complaints.

- “2. A place in which heat is applied to a body immersed in some substance. Thus,

- “A dry bath is made of hot sand, ashes, salt, or other matter, for the purpose of applying heat to a body immersed in them.

- “A vapor bath is formed by filling an apartmentwith hot steam or vapor, in which the body sweats copiously, as in Russia; or the term is used, for the application of hot steam to a diseased part of the body. Encyc. Tooke.

- “A metalline bath is water impregnated with iron or other metallic substance, and applied to a diseased part. Encyc. . .

- “3. A house for bathing. In some eastern countries, baths are very magnificent edifices.”

- Ranlett, William H., 1849, The Architect (1849; repr., 1976: 1:33)[30]

- “Design V.—Elevations, plans, details, ground plot and scenic view of a cottage in the Tudor style, designed for a country residence on the bank of the Bronx river, in Westchester County, N. Y. The tenement comprises ten acres of ground. . . The premises will contain a gardener’s lodge, summer-house, stone bridge, coach-house, bathhouse, and out-buildings, screened by ornamental shrubbery.”

Images

Inscribed

Samuel Vaughan, Plan of Bath [Berkeley Springs], VA [detail], 1787, from the diary of Samuel Vaughan, June–September 1787. “f. a large Bath for swimming” and “g. a Bath for Poor People.”

Samuel Vaughan, “Warm or Berkeley Springs, in Virginia,” 1787, from the diary of Samuel Vaughan, June–September 1787.

Charles Varlé, Project for the Improvement of the Square and the Town of Bath [detail], 1809. “F. addition of Bath.”

Anonymous, “Barrell Farm,” Pleasant Hill, 1817. “Bathing House” is located just below the poplar grove.

Sophie Madeleine du Pont, Spout bath at the Warm Springs (Berkeley Springs), 1837.

Frances Palmer, Plan and section of Villa at Oswego, New York, in William H. Ranlett, The Architect (1851), vol. 2, pl. 12. “bath-house, L.”

Associated

Sophie Madeleine du Pont, Octagonal Bath at Warm Springs (Berkeley Springs), 1837.

Attributed

Pierre Pharoux, Frontal view of two pavilions on the water for the city of Speranza, 1795.

Pierre Pharoux, Aerial view of two pavilions on the water for the city of Speranza, 1795.

Notes

- ↑ Carl Bridenbaugh, “Baths and Watering Places of Colonial America,” William and Mary Quarterly 3, no. 2 (April 1946): 152, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel Peters, A General History of Connecticut (London: Printed for the author, 1781), 174. A detailed description of a visit to Stafford Springs is recorded in John Adams’s diary in 1771, although he does not use the term “bath,” view on Zotero.

- ↑ Barbara G. Carson, “Early American Tourists and the Commercialization of Leisure,” in Of Consuming Interests: The Style of Life in the Eighteenth Century, ed. Cary Carson, Ronald Hoffman, and Peter J. Albert (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1994), 390, view on Zotero; Carol Shiels Roark, “Historic Yellow Springs: The Restoration of an American Spa,” Pennsylvania Folklife 24 (autumn 1974): 28–38, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Percival Reniers, The Springs of Virginia: Life, Love, and Death at the Waters, 1775–1900 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1941), 34, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Reniers, The Springs of Virginia, 26, view on Zotero; B. Carson, “Early American Tourists,” 393–97, view on Zotero. Cary Carson includes, along with his discussion of consumer behavior in America, a measured drawing of the oldest extant bathhouse in America, the Gentlemen’s bathhouse in Warm Springs (Berkeley Springs), Virginia (later West Virginia). See Cary Carson, “The Consumer Revolution in Colonial America: Why Demand?” in Of Consuming Interests: The Style of Life in the Eighteenth Century, ed. Cary Carson, Ronald Hoffman, and Peter J. Albert (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1994), 444–697, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bridenbaugh, “Baths and Watering Places,” 180–81, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Peter Benes, “Horticultural Importers and Nurserymen in Boston, 1719–1770,” in Plants and People: Annual Proceedings of the Dublin Seminar for New England Folklife, 1995, ed. Peter Benes (Boston: Boston University, 1996), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson, The Garden Book, ed. Edwin M. Betts (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1944), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bridenbaugh, “Baths and Watering Places,” 151–81, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Lillian B. Miller et al., eds., The Selected Papers of Charles Willson Peale and His Family, vol. 1, Charles Willson Peale: Artist in Revolutionary America, 1753–1791 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1983), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Eugene L. Schwaab and Jacqueline Bull, Travels in the Old South (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1973), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 William Bentley, The Diary of William Bentley, D.D., Pastor of the East Church, Salem, Massachusetts (Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1962), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Timothy Dwight, Travels; in New-England and New-York, 4 vols. (New Haven: T. Dwight, 1821), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Barbara Wells Sarudy, “Eighteenth-Century Gardens of the Chesapeake,” Journal of Garden History 9, no. 3 (July–September 1989): 104–59, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Edwards Caldwell, A Tour through Part of Virginia, in the Summer of 1808; Also, Some Account of the Islands of the Azores, ed. William M. E. Rachal (Richmond, VA: Dietz, 1951), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Lillian B. Miller et al., eds., The Selected Papers of Charles Willson Peale and His Family, vol. 3, The Belfield Farm Years, 1810–1820 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Lambert, Travels through Canada, and the United States of North America in the Years 1806, 1807, and 1808, 2 vols. (London: Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy, 1816), view on Zotero.

- ↑ James Kirke Paulding, Letters from the South, 2 vols. (New York: James Eastburn, 1817), view on Zotero.

- ↑ David Bailie Warden, A Chronographical and Statistical Description of the District of Columbia (Paris: Printed and sold by Smith, 1816), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Richard Saunders and Helen Raye, Daniel Wadsworth, Patron of the Arts (Hartford, CT: Wadsworth Atheneum, 1981), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Benjamin Silliman, Remarks Made on a Short Tour between Hartford and Quebec, in the Autumn of 1819 (New Haven, CT: S. Converse, 1824), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Lillian B. Miller et al., eds., The Selected Papers of Charles Willson Peale and His Family, vol. 5, The Autobiography of Charles Willson Peale (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Betty-Bright Low and Jacqueline Hinsley, Sophie du Pont, A Young Lady in America: Sketches, Diaries, & Letters, 1823–1833 (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1987), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William A. Alcott, “Embellishment and Improvement of Towns and Villages,” American Annals of Education 8, no. 8 (August 1838): 337–47, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Mason Hovey, “Notes on Gardens and Nurseries,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 16, no. 10 (October 1850): 461–62, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Fanning Watson, Annals of Philadelphia and Pennsylvania in the Olden Time; Being a Collection of Memoirs, Anecdotes, and Incidents of the City and Its Inhabitants, and of the Earliest Settlements of the Inland Part of Pennsylvania, from the Days of the Founders, 2 vols. (Philadelphia: E. Thomas, 1857), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Ephraim Chambers, Cyclopaedia, or An Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences. . . , 5th ed., 2 vols. (London: D. Midwinter et al., 1741), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. B. [John Beale] Bordley, Country Habitations (Philadelphia: Charles Cist, 1798), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William H. Ranlett, The Architect, 2 vols. (1849–51; repr., New York: Da Capo, 1976), view on Zotero.