Gray’s Garden

Overview

Alternate Names: Gray’s Ferry; Gray’s Ferry Tavern; Gray’s Tavern; Lower Ferry; Lower Ferry House

Site Dates: 1786–1789

Site Owner(s): George Gray I 1693–c. 1748; George Gray II 1725–1800; George Gray III 1757–1800; Robert Gray; George Weed;

Associated People: Samuel Vaughan 1720–1802, landscape designer;

Location: Philadelphia, PA

Condition: Demolished

Keywords: Alcove; Alley; Arbor; Avenue; Bath/Bathhouse; Bed; Border; Bower; Bridge; Cascade/Cataract/Waterfall; Chinese manner; Eminence; Fence; Flower garden; Fountain; Gate/Gateway; Greenhouse; Grotto; Grove; Hermitage; Icehouse; Labyrinth; Mound; Orchard; Parterre; Piazza; Picturesque; Pleasure ground/Pleasure garden; Plot/Plat; Pond; Promenade; Prospect; Seat; Shrubbery; Summerhouse; Temple; Thicket; View/Vista; Walk; Wilderness; Wood/Woods

Gray’s Garden was the earliest and most famous of several pleasure gardens that flourished near Philadelphia in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Its picturesque walks, greenhouse, and groves provided the setting for entertainments that attracted local pleasure-seekers as well as tourists passing through the city. Gray’s Garden was also a favorite location for patriotic civic ceremonies and welcoming parties.

History

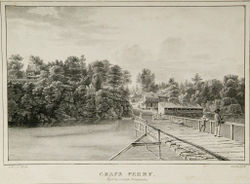

A flower garden on a hill overlooking the Schuylkill River was reportedly among the improvements that George Gray (1693–1748/49?) made at Lower Ferry, the river crossing that he operated a few miles south of Philadelphia. The garden provided a refined setting for the new inn Gray constructed as an enticement to travelers sometime before 1740. During the Revolutionary War, British troops destroyed the “elegant and spacious” flower garden, along with the ferry house, adjacent woods, and cedar fencing.[1] By that time, the ferry and surrounding property had passed to Gray’s son, also George Gray (1725–1800), of Whitby Hall. The younger Gray was a prominent patriot and public figure, serving in a number of political and military posts, including member (1772–1775) and speaker (1783–1784) of the Pennsylvania Assembly.[2] He was also a member of the American Philosophical Society (from January 1784) and one of the area’s largest landowners, having purchased additional parcels of land in the vicinity of Gray’s Ferry.[3] Prior to the war, he made numerous improvements to the ferry grounds, including carving stone steps to the elevated garden, as seen in a watercolor by Joshua Rowley Watson [Fig. 1].

After the war, the younger Gray’s sons, George (1757–1800) and Robert (b. 1759), assumed responsibility for operating the river crossing (by then a floating pontoon bridge) and repairing the damaged property. They re-established the inn as Lower Ferry House (also known as Gray’s Tavern) and in 1786 permitted the enterprising British merchant Samuel Vaughan to carry out an ambitious landscaping project that transformed twelve acres of hilly wilderness into a picturesque fantasyland.[4] As laid out by Vaughan, Gray’s Garden became the first American pleasure garden modeled on English example. Capitalizing on the natural drama of the hilly terrain—which lent itself to distant prospects and scenic overlooks—Vaughan's design dazzled visitors with an array of romantic features, including variegated plantings, meandering paths, arbors, a summerhouse, Chinese bridges, hermitages, grottoes, a piazza, and water features that included “one of the finest cascades in America.”[5] To accomplish all this, Vaughan reportedly hired an English gardener who directed a team of ten or so laborers.

Several years in the making, Gray’s Garden attracted curious visitors long before it opened officially to the public. Jacob Hiltzheimer and members of his family went to see “the great improvements made in the gardens” on April 13 and July 17, 1787. On the latter occasion, Hiltzheimer bumped into George Washington and “a number of gentlemen of the Federal Convention who were spending the afternoon there.”[6] Three days earlier, Samuel Vaughan had led a party of Convention delegates (including James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and George Mason) on an early morning visit to Bartram’s Garden, followed by a tour of Gray’s Garden. In his lengthy account of the visit, Manasseh Cutler noted that the landscape work at Gray’s had yet to be completed. A hillside labyrinth and a number of grottoes and hermitages were still under construction and lacked the effects of age “to give them that highly romantic air which they are capable of attaining.”[7] Cutler’s detailed description conveys a sense of the bewildering complexity of Gray’s Garden, with its superabundance of plantings and seemingly innumerable deviating paths, stimulating the imagination with thoughts of “all the apparatus of eastern fable,” but leaving the “mind really fatigued with so long a scene of pleasure”(view text).

The Gray brothers officially opened their garden to the public on May 20, 1789. In addition to “groves, arbours, . . . shrubs, trees and flowers, . . . summer houses, alcoves and seats,” they advertised free concerts, fine food and drink, a “spacious Saloon, for dances, clubs, or large dining parties,” and even fishing tackle upon request (view text) [Fig. 2]. The Grays also drew attention to their collection of exotic plants, cultivated in a towering, three-story greenhouse. They evidently offered some of their botanical specimens for sale. William Hamilton (whose estate, The Woodlands, neighbored Gray’s Garden) urged his private secretary to search local plant dealers for specimens of Arabian Jasmine, African Heath, and double myrtles “as good as Gray’s.” In 1792 he complained of his secretary’s failure to “properly secure von Rohrs agave at Gray’s,” as he “wish’d to prevent its getting into other hands.” For the same reason, Hamilton was eager to obtain the Grays’ specimens of Arbutus and Rose apple, “which however are priced so high that I do not imagine they will find a ready sale before my return.”[8]

The Grays hosted numerous public celebrations and ceremonies at their garden, for which they orchestrated elaborate botanical decorations, temporary architecture, and illuminations.[9] For example, when Washington passed through Philadelphia on April 20, 1789, en route to assume the presidency in New York, the Grays greeted him with an elaborate display of banners and state flags designed by Charles Willson Peale. The artist had also lined the pontoon bridge with artificial laurel hedges and terminated each end with a triumphal arch fashioned of laurel and pine [Fig. 3]. As the President passed beneath the western arch, a child (reportedly Peale’s young daughter, Angelica, in costume) lowered a laurel wreath onto his head.[10] On July 4, 1790, the Grays decorated the pontoon bridge with shrubbery, flowers, and state flags and, in one of the garden’s groves, erected a temple symbolic of the union of thirteen states, with thirteen “shepherds” and thirteen “shepherdesses” singing an ode to Liberty. By night, classical statuary in the garden was illuminated, along with portraits of Washington and an artificial island decorated with a farmhouse and garden. Two months later, on September 4, a grove at Gray’s Garden was the site of a private picnic, concert, and illumination held for the Washington family and 200 guests.[11] After witnessing one of these spectacles, the Pennsylvania congressman John Swanwick (1740–1798) penned “Lines Written at a Country Seat near This City, on Seeing Crouds [sic] Passing to the so justly Celebrated Garden of Messrs Grays,” one of several poems ostensibly inspired by the spectacular melding of art and nature at Gray’s Garden.[12]

From 1793 to 1803 Gray’s Garden continued as a pleasure garden under the management of George Weed. Thereafter, it faced competition from gardens located more centrally to Philadelphia, and become known chiefly for the excellence of the food and drink offered at the inn.[13] In the early 19th century, under a succession of proprietors, the landscape fell into disrepair and was no longer operated as a public place of entertainment.[14] The character of the site was altered further in 1838 by the construction of the Newkirk Viaduct crossing the Schuylkill River at Gray’s Ferry, providing the first direct rail connection between Philadelphia and Baltimore. To commemorate the viaduct’s completion, a fifteen-foot-high monument in the form of an obelisk, surrounded by a low iron fence, was erected on the grounds in 1839 [Fig. 4]. The monument was designed by Thomas Ustick Walter, who later designed the dome of the United States Capitol.[15] For travelers passing by on the train, the Newkirk Viaduct monument served as a bittersweet reminder of the garden that had once existed there. Directing his readers’ attention to the former site of Gray’s Garden, the author of the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad Guide noted nostalgically, “the utilitarianism of the age has shorn Gray’s garden of its beauties, and the banks of the ‘classic stream,’ which once echoed with festivities and mirth, now re-echo to the hoarse trumpet of the locomotive.”[16]

—Robyn Asleson

Texts

- Hiltzheimer, Jacob, July 17, 1787, diary entry (1893: 128)[17]

- “In the afternoon went with my wife, Mr. Matthew Clarkson, Mr. and Mrs. Barge to Mr. Gray’s ferry, where we saw the great improvements made in the garden—; summer houses and walks in the woods—and met General Washington with a number of gentlemen of the Federal Convention, who were spending the afternoon there.”

- Cutler, Manasseh, July 14, 1787 (1888: 1:274–79)[18]

- “ . . . This tavern is on the south side of the Schuylkill, at the foot of the floating bridge. . . There we were entertained with scenes romantic and delightful beyond the power of description. I know not how nor where to begin or end, nor can I give the faintest idea of this prodigy of art and nature. . . Nothing appears from the house, or in passing the street, that would attract the attention of the most inquisitive traveler, unless it be a flight of steps cut out of the solid rock at the east end of the house, by which you ascend to a beautiful grass plat, shaded with a number of large trees, in the rear of the house. . . From this grass plat we went into a piazza one story high, next the street, very pleasant, as it is in full view of the river. Here we breakfasted. Mr. Vaughan invited us to take a view of the Gardens. We returned to the grass plat, from which we ascended several glaces [gentle slopes] by a serpentine gravel walk, and came to the Green-house. It is a very large stone building, three stories in the front and two in the rear. The one-half of the house is divided lengthwise, and the front part is appropriated to a green-house, and has no chamber floors. It is finished in the completest manner for the purpose of arranging trees and plants in the most beautiful order. The windows are enormous. I believe some of them to be twenty feet in length, and proportionably wide. There is a fine gallery next the other part of the house, where company may view the vegetables to the best advantage. At this time, the trees and plants were removed into the open air, and the room whitewashed and as neat as a parlor. The other part of the house, which communicates with the gallery, is divided into Halls and small apartments, for the accommodation of several large companies (who would not wish to have intercourse) at the same time. All these apartments are handsomely furnished. On the top of the house is a spacious walk, where we had a delightful view of the city of Philadelphia. We then took a view of the contents of the green-house, beautifully arranged in the open air on the south of the garden. Here were most of the trees and fruits that grow in the hottest climates. Oranges, lemons, etc., in every stage from blossoms to ripe fruit; pine-apples in bloom, and those that were fully ripe. The flowers were numerous and extremely fragrant. We then rambled over the Gardens, which are large—seemed to be in a number of detached areas, all different in size and form. The alleys were none of them straight, nor were there any two alike. At every end, side, and corner, there were summer-houses, arbors covered with vines or flowers, or shady bowers encircled with trees and flowering shrubs, each of which was formed in a different taste. In the borders were arranged every kind of flower, one would think, that nature had ever produced, and with the utmost display of fancy, as well as variety. As we were walking on the northern side of the Garden, upon a beautiful glacis, we found ourselves on the borders of a grove of wood and upon the brow of a steep hill. Below us was a deep, shady valley, in the midst of which was a purling stream of water, meandering among the rocks in its way down to the river. At a distance, we could just see three very high arched bridges, one beyond the other. They were built in the Chinese style; the rails on the sides open work of various figures, and beautifully painted. We saw them through the grove, the branches of the trees partly concealing them, which produced the more romantic and delightful effect. As we advanced on the brow of this hill, we observed a small foot-path, which led by several windings into the grove. We followed it; and though we saw that it was the work of art, yet it was a most happy imitation of nature. It conducted us along the declivity of the hill, which on every side was strewed with flowers in the most artless manner, and evidently seemed to be the bounty of nature without the aid of human care. At length we seemed to be lost in the woods, but saw in the distance an antique building, to which our path led us. It is built of large stones, very low and singular in its form, standing directly over the brook in the valley. It instantly struck me with the idea of a hermitage, and I found that so it was called. Every thing was neat and clean about it, but we saw no inhabitant. We ventured, however, to open the door, which was large and heavy and seemed to grate upon its rusty hinges, and echoed a hoarse groan through the grove. We found several apartments, and at one end a fine place for bathing, which seems to be the design of the building. At this hermitage we came into a spacious graveled walk, which directed its course further along the grove, which was tall wood interspersed with close thickets of different growth. As we advanced, we found our gravel walk dividing itself into numerous branches, leading into different parts of the grove. We directed our course nearly north, though some of our company turned into the other walks, but were soon out of sight, and thought proper to return and follow us. We at length came to a considerable eminence, which was adorned with an infinite variety of beds of flowers and artificial groves of flowering shrubs. On the further side of the eminence was a fence, beyond which we perceived an extensive but narrow opening. When we came to the fence, we were delightfully astonished with the view of one of the finest cascades in America, which presented itself directly before us at the further end of the opening. A broad sheet of water comes over a large horizontal rock, and falls about seventy feet perpendicular. It is in a large river, which empties into the Schuylkill just above us. The distance we judged to be about a quarter of a mile, which being seen through the narrow opening in the tall grove, and the fine mist that rose incessantly from the rocks below, had a most delightful effect. Here we gazed with admiration and pleasure for some time, and then took a different route in our return through the grove, and followed a walk that led down toward the Schuylkill. Here the scene was varied. Toward the river the lands were more broken. The walks were conducted in every direction, over little eminences, or along their sides, or through a deep bottom or along a valley, with numerous other walks coming in or going out from the one that we followed. Indeed, the walks were nearly alike, only leading in different directions. This piece of ground in some parts is extremely rude, but those parts are improved to the best advantage; for here we found Grottoes wrought out of the sides of ledges of rocks, the entrance almost obscured by the shrubs and thickets that were placed before them, and the passage into them by a kind of labyrinth. There were several other hermitages, constructed in different forms; but the Grottoes and Hermitages were not yet completed, and some space of time will be necessary to give them that highly romantic air which they are capable of attaining. We crossed the deep valley with the purling stream at the lower end, next the river, where we had a fine view of the lofty Chinese bridges above us. Here is a curious labyrinth with numerous windings begun, and extends along the declivity of the hill toward the gardens, but has hardly yet received its form. At the bottom of the vale, and on the bank of the river, is a huge rock, which I judged to be at least fifteen feet high, and surrounded with tall spruces and cedars. On the top of it I observed a spacious summer-house, as I supposed, for I could see it only through the boughs of the trees. The roof was in the Chinese form. It was surrounded with rails of open work, and a beautiful winding staircase led up to it.

- “From this valley we ascended a steep precipice on to the grass plat in the rear of the house from which we set out. During the whole of this romantic, rural scene, I fancied myself on enchanted ground, and could hardly help looking out for flying dragons, magic castles, little Fairies, Knight-errants, distressed Ladies, and all the apparatus of eastern fable. I found my mind really fatigued with so long a scene of pleasure. This tract of ground, in some parts, consists of gentle risings and depressions; in others, hills and vales; and in others, rocky, rude, and broken. There is every variety that imagination can conceive, but the whole improved and embellished by art, and yet the art so blended with nature as hardly to be distinguished, and seems to be only an handmaid to her operations. On the side of the road opposite to the house is a high hill, which ends abruptly next the river, in a large extended rock, twenty feet high. In this rock a flight of steps is cut, in a winding or kind of lunette form, from the road to the top of the hill, wide enough for two or three persons to walk abreast, with little gutters on each side to conduct the water that runs down. At the summit of the hill you enter a grove of walnuts, oaks, and pines, under which are arranged benches for one hundred people to sit, several long tables, etc. This is the only work of art on this hill. But, under the trees and on the sides of the hill, are many blueberry, whortleberry, and bilberry bushes, raspberries, blackberries, and some other kinds of wild fruit. It affords a fine prospect down the Schuylkill and its opposite shore.

- “This tavern used to be no more than a common Inn, but Mr. Samuel Vaughan Sr., when he came from England a few years ago, was charmed with the situation, advised the present owner, who had just purchased it, and was an ambitious young fellow, to undertake these works, assuring him he would soon reimburse his expenses and accumulate a large estate from the company he would draw from Philadelphia. Mr. Vaughan promised to plan the works and furnish him with a gardener from England who would answer his purpose. This gardener is now with him, and he constantly employs about ten laborers under the gardener’s direction. The company from Philadelphia, we are told, far exceeded the Inn-keeper’s expectations, and he finds himself in a fair way to make a fortune.” back up to History

- Anonymous, August 1787, “Verses upon Gray’s Ferry” (Columbian Magazine 1: 607)[19]

- “A winding vale, with skill divine he [Jove] forms,

- “Secure from summer’s heat, and winter’s storms;

- “And Schuylkill here in gentle murmur glides:

- “Above the rest two rocks of equal size,

- “With their aspiring fronts assail the skies;

- “The one ascended, yields the glorious sight,

- “Where Delaware and Schuylkill's streams unite:

- “The other [rock] by the hand of art array'd,

- “Affords a mansion’s shelter and a forest’s shade. . .

- “Beyond these rocks, the vale obliquely bends

- “To where the Woodland's airy Mount ascends;

- “There down the steep a fountain gently slides,

- “Or swell'd with rain, rolls on its foamy tides,

- “Then through the vale in wild meanders flows,

- “Now hides its limpid head, now kindly shows.”

- Anonymous, May 19, 1787, Pennsylvania Packet (quoted in Stubbs 2013: 56)[20]

- “The expence [sic] is very moderate, and promotes domestic circulation, great part of it consisting in the consumption of our native delicacies. . . An agricultural people, as we are, should be fond of gardening and ornamental planting, [and pleasure gardens] awaken a taste so natural and noble, and by displaying the charms of our country will make us love it the more. [In addition] those rural entertainments are congenial with republican manners, and have a salutary influence on public liberty.”

- George and Robert Gray, May 20, 1789, broadside advertisement (1789: n.p.)[21]

- “THE Subscribers have spared no expence or attention to render the accommodations for travellers, and the entertainment of the citizens, at Gray’s FERRY, as complete as possible.

- “The Bridge over Schuylkill will be maintained in good repair, and attendance given, as usual, night and day.

- “The Gardens are kept in the neatest order, and are laid out with as much variety as the grounds would admit; are decorated with groves, arbours, and a great collection of shrubs, trees and flowers, and accommodated with summer houses, alcoves and seats.

- “The elegant new House in the garden is now finished, and consists of a spacious Saloon, for dances, clubs, or large dining parties, with several apartments for small companies.--From the Saloon there is a passage into

- “The Green House, which is furnished with an extensive collection of exotic plants, &c. in high perfection.” back up to History

- Constantia [Murray, Judith Sargent], June 1790, “Description of Gray’s Gardens, Pennsylvania” (Massachusetts Magazine 3: 413–17)[22]

- ”Did I not promise you in my last a jaunt to the Schuylkill Gardens? . . . Several gravel walks present—the left leading to the house. We ascend the glacis, five easy steps in the first, and ten in the second, produces us in the area exactly before the door, and we then command a full view of a romantick summer house, in the front of which is a whole length transparent picture of Columbia’s illustrious Chief [George Washington]—Fame, is crowning him with the laurel—the picture is as large as the life, and the likeness, it is said, is happily preserved. Underneath this summer house, is an ice house, convenient and well planned, and upon the right of this building is an oblong section of the garden, prettily enclosed, which is chiefly devoted to exotics.

- “Upon the grass plats, loose seats are thrown up and down, and tall trees of an umbrageous foliage form an ample shade. The serpentine gravel walks, which are irregularly regular, seem to point different ways; they, however, terminate in one object. If we proceed straight forward, we pass through an elegant arched gate, which seems to be guarded by the figure of a satyr, extremely well painted. But this, as well as all the smaller avenues, alike produces us in the wilderness, into which we enter, passing over a neat Chinese bridge, preparing with much pleasure to penetrate a recess so charming. It is indeed a wilderness of sweets, and the views instantly become romantically enchanting, the scene is every moment changing. Now, side long bends the path; then, pursues its winding way; now, in a straight line; then, in a pleasing labyrinth is lost, until, in every possible direction, it breaketh upon us, amid thick groves of pines, walnuts, chestnuts, mulberries, &c. &c. we seem to ramble, while at the same time, we are surprized [sic] by borders of the richest, and most highly cultivated flowers, in the greatest variety, which even from a royal parterre we might be led to expect.

- “Every gale comes forward loaded with perfumes, and by odoriferous breezes we are momently fanned. In the flower borders, the silver pine, the turin poplar, bay tree, and a variety of ever greens, are judiciously interspersed. By the bounteous hand of Nature the scene is apparently moulded, though we cannot admit the deception as to exclude from our idea her handmaid Art. On one hand, the lovely valley richly shaded, is fancifully adorned, the mountain laurel condescending to flourish there—and on the other, grass grown mounds variegate the view—here, the excavated cavern gives a degree of wildness to the prospect; and there, the tall woods, with their enfolding branches, insensibly disposeth the mind to all the pleasures of contemplation; while the bending river, breaking through the trees, largely contributes to beautify the whole. Suddenly, however, an open plain is outspread before us, and we are presented with a pleasing horizon—but as suddenly, thick trees again intervene, until at the extremity of the walks, a mill and a beautiful natural cascade terminates the prospect. At every turn shaded seats are artfully contrived, and the ground abounds with arbours, alcoves, and summer houses, which are handsomely adorned with odoriferous flowers. Among these the little federal temple claims the principal regard. It is the very edifice, that upon the celebration of the ratification of the constitution, was carried in triumphant procession through the streets of this metropolis; and, upon a gentle acclivity, upon the summit of a green mound infixed, it hath now obtained a basis. It is a Rotunda, its cupola is supported by thirteen pillars handsomely finished; their base, is to receive the cypher of the several states, which they represent, with a star upon every capital, and its top is crowned with the figure of Plenty grasping the cornucopia and other insignia. The ascent to this Temple is easy, and we gain it by the semicircular steps neatly turned, and the view therefrom is truly interesting.”

- Anonymous, July 6, 1790, “Grays Gardens,” Federal Gazette, and Philadelphia Daily Advertiser (quoted in Beamish 2015: 202)[23]

- “How shall we attempt to describe this enchanting spot, this fairy ground of pleasure and festivity, where new scenes met the eye at every step. The splendid, every where diversified, illumination, the superb fireworks, the distant waterfall, faintly seen through the trees, attracting the attention and pointing itself out by its murmuring sound, the ship union elegantly lighted up, and shining with superior lustre, the artificial island with its farmhouse and garden, these and many other scenes almost pained the eye with delight.”

- Wansey, Henry, June 9, 1794, diary entry (1970: 112)[24]

- “On our return [from Bartram’s Garden] we stopped at Gray’s Gardens, a place of entertainment, like Bagnigge Wells. The ground has every advantage of hill and dale, for being laid out in great variety; and it is neatly decorated with alcoves, arbours, shady walks, etc. It stands at the ferry of the Skuylkill [sic], about four miles from the city, and its much frequented by parties of pleasure from thence. This river makes a most beautiful meander just at this place; the fine curve it forms, appearing mathematically true.

- “We had tea, coffee, syllabubs, cakes, etc. etc. for all which, we paid only half a dollar each, horses’ hay included. The river is pretty wide at this place, very rapid at times, and ebbs and flows six feet: on these accounts, no common bridge will do, as the abutments could not stand long; it is therefore a floating bridge, which rises and falls with the tide. . . .”

- Costa Pereira Furdado de Mendonça, Hipólito José da, April 10, 1799, diary entry (quoted in Smith 1954: 104–5)[25]

- “I have been to Gray’s Ferry to a place of recreation on the banks of the Schuylkill. It has the most picturesque location in the world, with the views of the bridge, the woods, the house itself, etc., etc. In the summer everyone in the city goes out there to sup or dine or have a picnic meal. It costs nothing to enter, but you pay for what you eat and drink. It is 3 miles distant from the city. I have also been to another similar establishment called Harrowgate 6 miles in the direction of Trenton. The location is not so fine as that of Gray’s Ferry, but there the garden is larger and more tidy. I am told that the two places are much frequented in the summer months.”

- Wilson, Alexander, 1800, “The Invitation” (Literary Magazine and American Register 2: 265–67)[26]

- “From Schuylkill's rural banks overlooking wide

- “The glitt'ring pomp of Philadelphia’s pride,

- “From laurel groves that bloom forever here,

- “I hail my dearest friend with heart sincere. . .

- “Come, then, O come! your burning streets forego.

- “Your lanes and wharves, where winds infectious blow.

- “Where sweeps and oystermen eternal growl,

- “Carts, crowds, and coaches harrow up the soul,

- “For deep, majestic woods, and op'ning glades.

- “And shining pools, and awe-inspiring shades;

- “Where fragrant shrubs perfume the air around.

- “And bending orchards kiss the flow'ry ground.

- “And luscious berries spread a feast for Jove,

- “And golden cherries stud the boughs above;

- “Amid these various sweets thy rustic friend

- “Shall to each woodland haunt thy steps attend,

- “His solitary walks, his noontide bowers,

- “The old associates of his lonely hours. . .”

- Wilson, Alexander, August 10, 1804, “A Rural Walk. The Scenery drawn from Nature,” Gray’s Ferry (1876: 1:359, 361–64)[27]

- A wide extended waste of wood,

- “Beyond in distant prospect lay;

- “Where Delaware’s majestic flood

- “Shone like the radiant orb of day. . .

- “There market-maids, in lovely rows,

- “With wallets white, were riding home;

- “And thund’ring gigs, with powder’d beauxs [sic],

- “Through Gray’s green festive shade to roam.

- “There Bacchus fills his flowing cup,

- “There Venus’ lovely train are seen;

- “There lovers sigh, and gluttons sup,

- “But dearer pleasures warm my heart,

- “And fairer scenes salute my eye;

- “As thro' these cherry-rows I dart

- “Where Bartram’s fairy landscapes lie.”

- Anonymous [“M.”], February 1829, “Gray’s Ferry, Inn, and Garden” (Casket 4: 73–74)[28]

- “Mr. [George] Gray [d. 1740] . . . opened an inn, and expended much money in improving the rural site as a flower garden, on the commanding eminence to the north of his mansion, and overlooking the serpentine river which washes its borders.—Multitudes flocked from the city to this now celebrated place of entertainment. . .

- “He [George Gray’s son, George (1725–1800)] became possessed in fee of this valuable estate. His attention was drawn to its immediate improvement: he leveled and widened the present road, through the rock, to the river, and had those solid steps, by which visiters [sic] ascend to the garden, and to Say’s place on the south, hewn out of the same primitive and permanent formation. . .

- “By order of the republican Committee of Safety, (of which he was an active and efficient one,) the rope ferry was destroyed, and the scows sunk in the deep channel of the Delaware river. The British soon afterwards took possession of the premises, where they established an outpost. The rabble soldiery destroyed the elegant and spacious garden, consumed the cedar fencing, cut down a part of the woods, and burnt the remainder. Mr. Gray’s estate extended over the river on the eastern side, and amongst other improvements, he had erected a good substantial brick dwelling, on the north side of the main road, about fifty yards from the river.—This house the British also occupied; and when they evacuated the city, to consummate the work of devastation, gave it to the flames. . . .

- “Mr. Gray’s sons, George [1757–1800] and Robert [b. 1759], succeeded their father as tenants of the repaired premises, at the close of the war of independence. They laid out a beautiful garden, and built the spacious green-house, above the ferry house, where, since their tenant days, many a time and oft, hundreds now living, and some thousands dead, have tripped the light fantastic toe, to merry music. . .

- “About the year 1794, the late George Weed succeeded the Grays, as the tenant, under their father, George. Possessing amiable and affable manners, he was eminently successful in establishing a name and fame for this place of entertainment, equaling, if not surpassing, any of its competitors, at least in constant, abundant, and profitable custom. The garden and promenades which had been laid out by the Grays, at great expense and with exquisite taste, were preserved. Embowered summer-houses, temples, groves, alcoves, and all the convenient embellishments and appurtenances of a pleasant summer retreat, arose, as if by magic. Here the senses were regaled, in the verdant seasons, with the perfumes of indigenous exotic shrubbery, plants, and flowers. At night there were occasional illuminations, concerts, fireworks, & c. & c. Engraved brass plates, here and there affixed to the stately trees in the garden notified, the visiters against certain trespasses. It was briefly a gentle warning for all, noli me tangere—these are forbidden fruits. . .

- “It would indeed be a needless reminiscence to describe the cultivated grounds, as they were laid out under the superintendence of the brothers Gray, and preserved by Mr. Weed and the Ogdens. It would indeed be a painful task to contrast them with their present dilapidated and wasteful condition. Memory will supply the place of minute description to the old and middle aged who know what Gray’s gardens once were; and all of the present generation, younger in years, who would probably be interested in the description, can readily imagine, from a present view, and this sketch, assisted by a little imagination, what a beautiful and picturesque place of public entertainment and agreeable promenade the lads and lasses of Philadelphia, and the neighbouring country, enjoyed in days of yore. It is a lamentable fact that no such place exists at this time in the environs of Philadelphia, notwithstanding her unbounded wealth and trebled population. Even the far-famed, splendid gardens, fountains, baths, and fish-ponds of Harrowgate, near Frankford, have been suffered to go to decay under the mouldering and unsparing hand of time, because the renovating hand of art has been unnerved, by the want of adequate public favour, and generous support to the enterprising proprietors.”

Images

James Trenchard after Charles Willson Peale, “An East View of Gray’s Ferry, on the River Schuylkill,” in Columbian Magazine 1 (August 1787): pl. opp. p. 565.

Joshua Rowley Watson, The Lower Bridge on Schuylkill at Gray’s Ferry 5 [-]ber 1816, 1816.

Other Resources

Philadelphia Architects and Buildings

The Redemption of the Lower Schuylkill

Notes

- ↑ Anonymous [“M.”], “Gray’s Ferry, Inn, and Garden,” Casket; or, Flowers or Literature, Wit and Sentiment 4, no. 2 (February 1829): 73, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Robert Patterson Robins, James Coultas, and Thomas Stretch, “Colonel James Coultas, High Sheriff of Philadelphia, 1755–1758,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 11 (1887): 50, 56, 57, view on Zotero; Mary Stanley Field Liddell, The Hon. George Gray, 4th of Philadelphia: His Ancestors & Descendants (Ann Arbor: Privately printed, 1940), view on Zotero.

- ↑ See “Mapping West Philadelphia: Landowners in October 1777,” a project hosted by the University of Pennsylvania Archives. See also Dora Harvey Develin, Historic Lower Merion and Blockley (Bala, PA: Privately printed, 1922), 94, 96, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Naomi Stubbs, Cultivating National Identity through Performance: American Pleasure Gardens and Entertainment (New York: Palgrave Mamillan, 2013), 11, 48, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Manasseh Cutler, Life, Journals and Correspondence of Rev. Manasseh Cutler, LL.D., ed. William Parker Cutler and Julia Perkin Cutler, 2 vols. (Cincinnati: Robert Clarke & Co., 1888), 1:276–77, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jacob Hiltzheimer, Extracts from the Diary of Jacob Hiltzheimer of Philadelphia, 1765–1798, ed. Jacob Cox Parsons (Philadelphia: William F. Fell & Co., 1893), 124, 128, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Cutler 1888, 1:277, view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Hamilton and Benjamin H. Smith, “Some Letters from William Hamilton, of the Woodlands, to His Private Secretary (Concluded),” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 29 (1905): 257–67 260, 264, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Stubbs 2012, 12, 32, 56, view on Zotero; Harold Donaldson Eberlein and Cortlandt Van Dyke Hubbard, “The American 'Vauxhall' of the Federal Era Article Stable,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 68 (April 1944): 163–65, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Karen Stanworth, “Rhetoric, Ritual, and the Fashioning of Public Memory in Washington’s America,” Social History/Histoire Sociale 29 (1996): 317–21, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Thomas Scharf and Thompson Westcott, History of Philadelphia, 1609–1884, 3 vols. (Philadelphia: L. H. Everts & Co., 1884), 1:464, view on Zotero; 2:942–43, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Swanwick, Poems on Several Occasions (Philadelphia: F. and R. Bailey, 1797), 102–104, view on Zotero. See also Eugene L. Huddleston, “Poetical Descriptions of Pennsylvania in the Early National Period,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 93 (October 1969): 493–95, view on Zotero; James Southall Wilson, Alexander Wilson, Poet Naturalist: A Study of His Life with Selected Poems (New York and Washington: Neale Publishing Company, 1906), 59–60, 63–64, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Eberlein and Hubbard 1944, 165–67, view on Zotero.

- ↑ W. A. Newman Dorland, “The Second Troop Philadelphia City Cavalry (continued),” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 46 (1922): 73, view on Zotero; Scharf and Westcott 1888, 2:922, 944, view on Zotero; Anonymous [“M.”] 1829, 74, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles P. Dare, Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad Guide: Containing a Description of the Scenery, Rivers, Towns, Villages, and Objects of Interest Along the Line of Road (Philadelphia: Fitzgibbon & Van Ness, 1856), 115–20, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Dare 1856, 118, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Hiltzheimer 1893, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Cutler 1888, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, “Verses upon Gray’s Ferry,” Columbian Magazine 1, no. 12 (August 1787): 607–608, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Stubbs 2013, view on Zotero.

- ↑ George Gray and Robert Gray, “Broadside Advertising Gray’s Ferry,” May 29, 1789, Printed Ephemera Collection, Library of Congress, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Constantia, “Description of Gray’s Gardens, Pennsylvania,” Massachusetts Magazine 3 (June 1790), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anne Beamish, “Enjoyment in the Night: Discovering Leisure in Philadelphia’s Eighteenth-Century Rural Pleasure Gardens,” Studies in the History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes 35, no. 3 (2015): 198–212, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Henry Wansey, Henry Wansey and His American Journal, ed. David John Jeremy (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1970), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Robert C. Smith, “A Portuguese Naturalist in Philadelphia, 1799,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 78 (1954), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alexander Wilson, “The Invitation. Addressed to Mr. C. . .s [Charles] O. . .r [Orr],” Literary Magazine and American Register 2, no. 10 (July 1804): 265–67, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alexander Wilson, The Poems and Literary Prose of Alexander Wilson, the American Ornithologist, ed. Alexander B. Grosart, 2 vols. (Paisley: Alex. Gardner, 1876), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous [“M.”] 1829, view on Zotero.