Difference between revisions of "View/Vista"

V-Federici (talk | contribs) m |

V-Federici (talk | contribs) m |

||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

In urban settings, where lot size and the proximity of buildings limited sightlines into the distance, gardens often reflected treatises’ instructions to enhance views with smaller property. Such structures as [[temple]]s or [[summerhouse]]s were placed in gardens to serve as both focal points and viewing platforms (see [[Belvedere]]). These effects could also be achieved without building; in 1758 Theophilus Hardenbrook advertised designs for “Niche’s eyetraps ''trompe l’oeil'', to represent a building, terminating a [[walk]], or to hide some disagreeable object” in the New York Gazette. Treatises also suggested enhancing small gardens by laying out [[walk]]s or [[terrace]]s with converging (rather than parallel) sides to create the impression of greater depth. Similarly, such features as alleys or [[avenue]]s with dimensions that appeared to converge created the illusion of distance from the viewer. | In urban settings, where lot size and the proximity of buildings limited sightlines into the distance, gardens often reflected treatises’ instructions to enhance views with smaller property. Such structures as [[temple]]s or [[summerhouse]]s were placed in gardens to serve as both focal points and viewing platforms (see [[Belvedere]]). These effects could also be achieved without building; in 1758 Theophilus Hardenbrook advertised designs for “Niche’s eyetraps ''trompe l’oeil'', to represent a building, terminating a [[walk]], or to hide some disagreeable object” in the New York Gazette. Treatises also suggested enhancing small gardens by laying out [[walk]]s or [[terrace]]s with converging (rather than parallel) sides to create the impression of greater depth. Similarly, such features as alleys or [[avenue]]s with dimensions that appeared to converge created the illusion of distance from the viewer. | ||

| − | Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe has commented that in England the importance of the creation of views and prospects “became apparent when the enclosed medieval walled garden gradually expanded into walled gardens of more than one compartment—preparing the way for a unity of design in the 17th c.”<ref>Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe, “Vista,” in ''Oxford Companion to Gardens'', ed. Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe et al. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), 590, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/S392BPJ8 view on Zotero].</ref> In England the importance of views into the countryside increased as a principle of garden design and as an aspect of changing land use and property-holding practices.<ref>For an example of the design practices used in creating views and prospects in eighteenth-century English gardens, see Douglas Chambers, “Prospects and the Natural Beauties of Places: Joseph Spence,” in ''The Planters of the English Landscape Garden'' (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1993), 164–76, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/S3BW6ZQK view on Zotero]. For a discussion of changing land-use practices and their implications on the organization of sight in landscape gardening, see Denis E. Cosgrove, ''Social Formation and Symbolic Landscape'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984), 189–222, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/NZTXKTCT view on Zotero]; Raymond Williams, ''The Country and the City'' (London: Palladin, 1973) [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/TR28NC32 view on Zotero]; Simon Pugh, ed., ''Reading Landscape: Country, City, Capital'' (Manchester, England: Manchester University Press, 1990) [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/9T4DIAXW view on Zotero], including the essay by John Barrell, “The Public Prospect and the Private View: the Politics of Taste in Eighteenth-Century Britain,” 19–40, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/DF29TKTA view on Zotero].</ref> For historians of American gardens, understanding the visual organization of space is equally important not only because it was a fundamental principle of imported garden design, but also because it was a key factor in the design of gardens in America’s unique political, economic, and social setting. Abigail Adams’s poetic rendering of the view from Richmond Hill, New York, in 1789 evokes not only a romantic view of nature but also a vision of American estates as villas, linking the new nation to a past era of republican ideals.<ref>For a fuller discussion of the villa in the New World, see James Ackerman, ''The Villa: Form and Ideology of Country Houses'' (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/2EC879QB view on Zotero].</ref> In 1824, Benjamin Silliman described Monte Video in Connecticut as poised between a [[wilderness]] of “rocks and forest” and a “vast sheet of cultivation, filled with inhabitants.” His evocative description expresses the landscape’s capacity to inspire both a sense of quiet contemplation and a connection to the industry and “frolicks” of village life. | + | Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe has commented that in England the importance of the creation of views and prospects “became apparent when the enclosed medieval walled garden gradually expanded into walled gardens of more than one compartment—preparing the way for a unity of design in the 17th c.”<ref>Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe, “Vista,” in ''Oxford Companion to Gardens'', ed. Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe et al. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), 590, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/S392BPJ8 view on Zotero].</ref> In England the importance of views into the countryside increased as a principle of garden design and as an aspect of changing land use and property-holding practices.<ref>For an example of the design practices used in creating views and prospects in eighteenth-century English gardens, see Douglas Chambers, “Prospects and the Natural Beauties of Places: Joseph Spence,” in ''The Planters of the English Landscape Garden'' (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1993), 164–76, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/S3BW6ZQK view on Zotero]. For a discussion of changing land-use practices and their implications on the organization of sight in landscape gardening, see Denis E. Cosgrove, ''Social Formation and Symbolic Landscape'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984), 189–222, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/NZTXKTCT view on Zotero]; Raymond Williams, ''The Country and the City'' (London: Palladin, 1973) [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/TR28NC32 view on Zotero]; Simon Pugh, ed., ''Reading Landscape: Country, City, Capital'' (Manchester, England: Manchester University Press, 1990), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/9T4DIAXW view on Zotero], including the essay by John Barrell, “The Public Prospect and the Private View: the Politics of Taste in Eighteenth-Century Britain,” 19–40, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/DF29TKTA view on Zotero].</ref> For historians of American gardens, understanding the visual organization of space is equally important not only because it was a fundamental principle of imported garden design, but also because it was a key factor in the design of gardens in America’s unique political, economic, and social setting. Abigail Adams’s poetic rendering of the view from Richmond Hill, New York, in 1789 evokes not only a romantic view of nature but also a vision of American estates as villas, linking the new nation to a past era of republican ideals.<ref>For a fuller discussion of the villa in the New World, see James Ackerman, ''The Villa: Form and Ideology of Country Houses'' (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/2EC879QB view on Zotero].</ref> In 1824, Benjamin Silliman described Monte Video in Connecticut as poised between a [[wilderness]] of “rocks and forest” and a “vast sheet of cultivation, filled with inhabitants.” His evocative description expresses the landscape’s capacity to inspire both a sense of quiet contemplation and a connection to the industry and “frolicks” of village life. |

Understanding the visual logic of American gardens has been particularly important in deciphering gardens as social commentary. For example, the reconstruction of specific viewing platforms, focal points, and openings in the visual barriers of a garden ([[wall]]s, [[fence]]s, rows of trees) provides valuable information about the ways in which people were intended to circulate in a garden.<ref>Elizabeth Kryder-Reid, “The Archaeology of Vision in Eighteenth-Century Chesapeake Gardens,” ''Journal of Garden History'' 14 (Spring 1994): 42–54, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/IJX4M93V view on Zotero], and Kryder-Reid, “Sites of Power and the Power of Sight: Vision in the California Mission Landscape,” in Dianne Harris and D. Fairchild Ruggles, ''Sites Unseen: Landscape and Vision'' (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2007), 181–212, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/8SGWDUKH view on Zotero].</ref> At Fairmount Park in Philadelphia, for instance, the stairs and viewing [[pavilion]]s created an explicit route through the grounds with carefully orchestrated views that are apparent in myriad illustrations and descriptions of the site. In another example, the triangular terraced garden built by Charles Carroll of Carrollton in Annapolis during the 1770s created very different visual effects depending upon where the viewer stood. A passerby on Spa Creek saw [[terrace]]s that elevated and accentuated an impressive Georgian brick house. A visitor permitted to stroll to the top [[terrace]] was treated to a sweeping view of the creek and countryside beyond, an effect enhanced by the foreshortening of the [[terrace]]s and [[Fall/Falling_garden|falls]], the placement of [[pavilion]]s at the ends of the sea [[wall]], and the spreading angle of the brick [[wall]] marking the garden’s hypotenuse. Only those permitted into the house, with its privileged views overlooking the [[terrace]]s, gained the vantage point to appreciate the garden geometry with its 3–4–5 proportions and [[parterre]] planting patterns. | Understanding the visual logic of American gardens has been particularly important in deciphering gardens as social commentary. For example, the reconstruction of specific viewing platforms, focal points, and openings in the visual barriers of a garden ([[wall]]s, [[fence]]s, rows of trees) provides valuable information about the ways in which people were intended to circulate in a garden.<ref>Elizabeth Kryder-Reid, “The Archaeology of Vision in Eighteenth-Century Chesapeake Gardens,” ''Journal of Garden History'' 14 (Spring 1994): 42–54, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/IJX4M93V view on Zotero], and Kryder-Reid, “Sites of Power and the Power of Sight: Vision in the California Mission Landscape,” in Dianne Harris and D. Fairchild Ruggles, ''Sites Unseen: Landscape and Vision'' (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2007), 181–212, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/8SGWDUKH view on Zotero].</ref> At Fairmount Park in Philadelphia, for instance, the stairs and viewing [[pavilion]]s created an explicit route through the grounds with carefully orchestrated views that are apparent in myriad illustrations and descriptions of the site. In another example, the triangular terraced garden built by Charles Carroll of Carrollton in Annapolis during the 1770s created very different visual effects depending upon where the viewer stood. A passerby on Spa Creek saw [[terrace]]s that elevated and accentuated an impressive Georgian brick house. A visitor permitted to stroll to the top [[terrace]] was treated to a sweeping view of the creek and countryside beyond, an effect enhanced by the foreshortening of the [[terrace]]s and [[Fall/Falling_garden|falls]], the placement of [[pavilion]]s at the ends of the sea [[wall]], and the spreading angle of the brick [[wall]] marking the garden’s hypotenuse. Only those permitted into the house, with its privileged views overlooking the [[terrace]]s, gained the vantage point to appreciate the garden geometry with its 3–4–5 proportions and [[parterre]] planting patterns. | ||

Revision as of 16:23, January 29, 2020

History

Travelers’ accounts of their journeys through the early American colonies contain many descriptions of extensive views and fine prospects. The frequent repetition of these and the related terms vista, “eminence,” and by the mid-19th century, “panorama,” suggests the importance of views and view-making in the perception, design, and representation of American landscapes.[1] The significance of composing a view in the landscape is echoed in the visual record of American gardens. Among the most common images of gardens are those framing the façade of the house and those taking a view from the house out toward the landscape.

As Antoine-Joseph Dezallier d’Argenville noted in 1712, one aspect of a “good situation, is, the View and Prospect of a fine Country,” and American property owners often sited their houses with this advice in mind. Planters situated their houses along well-traveled rivers and overlooking harbors, both capturing water views and creating highly visible architectural statements of their status and wealth [Figs. 1 and 2]. As at Monte Video [Fig. 3], houses were often sited on eminences to benefit from the natural topography. Gardens built around such houses took full advantage of their natural settings, and treatise writers such as A. J. Downing (1850) admonished gardeners to “study the character of the place” so as not to “shut out and obstruct the beauty of prospect which nature has placed before your eyes.” The frequent use of the words “command” and “commanding” by visitors recording their impressions indicates the assertion of ownership and control that was so clearly an aspect of the visual presentation of these estates. Water, topographic relief, a variety of rock formations, and vegetal and geological diversity were all prized components of views. Distance was also a measure of merit, not only contributing to the beauty of the scene, but also claiming the breadth of “command” over the countryside.

The term “vista,” while less commonly used than the related terms “prospect” and “view,” was similar in its designation of views created within the garden or looking out of the garden into the surrounding landscape. The term “vista” also carried the more particular connotation, as Thomas Sheridan noted in 1789 and Noah Webster in 1850, of the sight lines that created a view, whether made by an avenue, a meadow, or a space between trees. A vista within the garden was generally terminated by a focal point, such as the Chinese temple at Judge William Peters's Belmont Mansion, near Philadelphia. Even more common are descriptions of vistas from the garden to the world beyond. John Parke Custis (1717), Hannah Callender Sansom (1762), George Washington (1785), and Thomas Jefferson (1804) all used the term to describe framed views created by land cleared of trees (see Prospect).

Views were carefully planned and manipulated by a variety of techniques. The architecture of the dwelling often included exterior viewing platforms such as porches, piazzas, porticos, and verandas [Fig. 4]. Views of the house often were choreographed by carefully designed approaches, which allowed a visitor to catch glimpses of the house as he or she arrived and departed. As an 1837 article in the Horticultural Register noted, the view should be “so divided into different scenes or compartments” by various types of vegetation. Garden buildings or seats, such as those seen at Montgomery Place [Fig. 5], and those placed under a cluster of trees in Charles Fraser's painting of Rice Hope [Fig. 6], punctuated the landscape with invitations to pause and to admire the vista. Distant views were framed by plantings or by pruned trees, as at The Woodlands and at Springland [Fig. 7]. Their composition was also influenced by elevated mounts, such as those flanking the front gates of Mount Vernon; or by openings in hedges, trees, and walls [Fig. 8].

Another element of view-making was the use of barriers (such as walls, fences, and hedges) to screen less picturesque elements of a plantation. This technique was reported in 1790 in a description of the Elias Hasket Derby Farm in Peabody, Mass. John Trumbull’s 1792 plan for Yale College included instructions for a similar barrier that would provide a screen for the nose as well as the eyes. Inscribed on the plan is the directive that “The Temples of Cloacina [or priveys] (which it is too much the custom of New England to place conspicuously), I would wish to have concealed as much as possible, by planting a variety of Shrubs, such as Laburnums, Lilacs, Roses, Snowballs, Laurels, &c.”[2]

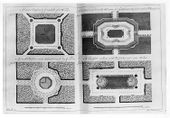

In urban settings, where lot size and the proximity of buildings limited sightlines into the distance, gardens often reflected treatises’ instructions to enhance views with smaller property. Such structures as temples or summerhouses were placed in gardens to serve as both focal points and viewing platforms (see Belvedere). These effects could also be achieved without building; in 1758 Theophilus Hardenbrook advertised designs for “Niche’s eyetraps trompe l’oeil, to represent a building, terminating a walk, or to hide some disagreeable object” in the New York Gazette. Treatises also suggested enhancing small gardens by laying out walks or terraces with converging (rather than parallel) sides to create the impression of greater depth. Similarly, such features as alleys or avenues with dimensions that appeared to converge created the illusion of distance from the viewer.

Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe has commented that in England the importance of the creation of views and prospects “became apparent when the enclosed medieval walled garden gradually expanded into walled gardens of more than one compartment—preparing the way for a unity of design in the 17th c.”[3] In England the importance of views into the countryside increased as a principle of garden design and as an aspect of changing land use and property-holding practices.[4] For historians of American gardens, understanding the visual organization of space is equally important not only because it was a fundamental principle of imported garden design, but also because it was a key factor in the design of gardens in America’s unique political, economic, and social setting. Abigail Adams’s poetic rendering of the view from Richmond Hill, New York, in 1789 evokes not only a romantic view of nature but also a vision of American estates as villas, linking the new nation to a past era of republican ideals.[5] In 1824, Benjamin Silliman described Monte Video in Connecticut as poised between a wilderness of “rocks and forest” and a “vast sheet of cultivation, filled with inhabitants.” His evocative description expresses the landscape’s capacity to inspire both a sense of quiet contemplation and a connection to the industry and “frolicks” of village life.

Understanding the visual logic of American gardens has been particularly important in deciphering gardens as social commentary. For example, the reconstruction of specific viewing platforms, focal points, and openings in the visual barriers of a garden (walls, fences, rows of trees) provides valuable information about the ways in which people were intended to circulate in a garden.[6] At Fairmount Park in Philadelphia, for instance, the stairs and viewing pavilions created an explicit route through the grounds with carefully orchestrated views that are apparent in myriad illustrations and descriptions of the site. In another example, the triangular terraced garden built by Charles Carroll of Carrollton in Annapolis during the 1770s created very different visual effects depending upon where the viewer stood. A passerby on Spa Creek saw terraces that elevated and accentuated an impressive Georgian brick house. A visitor permitted to stroll to the top terrace was treated to a sweeping view of the creek and countryside beyond, an effect enhanced by the foreshortening of the terraces and falls, the placement of pavilions at the ends of the sea wall, and the spreading angle of the brick wall marking the garden’s hypotenuse. Only those permitted into the house, with its privileged views overlooking the terraces, gained the vantage point to appreciate the garden geometry with its 3–4–5 proportions and parterre planting patterns.

The organization of vision may also provide information regarding the social hierarchy that is encoded in gardens. For instance, Dell Upton has argued that the terraced gardens of such plantations as John Tayloe II’s Mount Airy in Richmond County inscribed the status of Virginia’s whites and blacks into the topography. The landscape design of gates, ramps, terraces, and walks created a series of physical and social hurdles that each individual had to navigate differently, depending on his or her social standing in colonial society.[7]

—Elizabeth Kryder-Reid

Texts

Usages

- Custis, John Parke, April 1717, describing Gov. Alexander Spotswood’s improvements to the gardens of the Governor’s Palace, Williamsburg, VA (quoted in Martin 1991: 38)[8]

- “I happened to be at the Governors, and he was pleased to ask my consent, to cut down some trees that grew on my Land to make an opening, I think he called it a visto, and told me would cut nothing but what was only fitt [sic] for the fire. . . As to the clearing his visto, he cut down all before him such a wideness as he thought fitt [sic].”

- Anonymous, May 22, 1749, describing the dwelling house of Alexander Garden, Charleston, SC (South Carolina Gazette)

- “From the house Ashley and Cooper rivers are seen, and all around are visto’s and pleasant prospects.”

- Ball, Joseph, September 8, 1758, describing property in Virginia (Library of Congress, Joseph Ball Letterbook)

- “I have a Strang Hankering after a bit of Land upon Linhaven Creek. I would have it on the West or South side where it is Saved already. I want no more than fifty Acres. It must be bounding upon the Creek side; nigh a good Spring: and where I may have a full View of the Sea.”

- Sansom, Hannah Callender, June 30, 1762, diary entry describing Belmont, estate of William Peters, near Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Callender 2010: 183)[9]

- “. . . from these Windows down a Wisto terminated by an Obelisk. . . we left the garden for a wood cut into Visto’s, in the midst a chinese temple, for a summer house, one avenue gives a fine prospect of the City, with a Spy glass you discern the houses distinct, Hospital, & another looks to the Oblisk.”

- Eddis, William, October 1, 1769, describing the Governor’s House, Annapolis, MD (1792: 17)[10]

- “The garden is not extensive, but it is disposed to the utmost advantage; the centre walk is terminated by a small green mount, close to which the Severn approaches; this elevation commands an extensive view of the bay, and the adjacent county. . . there are but few mansions in the most rich and cultivated parts of England, which are adorned with such splendid and romantic scenery.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, 1771, describing Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, VA (1944: 26)[11]

- “open a vista to the millpond, river, road, etc. qu, if a view to the neighboring town would have a good effect?”

- Anonymous, January 28, 1771, describing the Vauxhall Garden, New York, NY (New York Gazette)

- “The Commodious house and large gardens, in the out-ward of this city, known by the name of VAUX-HALL; the situation extremely pleasant, having a very extensive view both up and down the North-River.”

- Anburey, Thomas, September 2, 1781, describing the Moravian community in Bethlehem, PA (1781; repr., 1969: 2:513)[12]

- “The house of the single men is upon the same principle as that of the women; upon the roof of which is a Belvidere, from whence you have not only a most delightful prospect, but a distinct view of the whole settlement.”

- Shippen, Thomas Lee, December 31, 1783, describing Westover, seat of William Byrd III, on the James River, VA (1952: n.p.)[13]

- “Imagine then a room of 20 feet square. . . and commanding a view of a prettily falling grass plat. . . about 300 by 100 yards in extent an extensive prospect of James River and of all the Country and some Gentlemen’s seats on the other side.”

- Washington, George, March 15, 1785, describing Mount Vernon, plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (Jackson and Twohig, eds., 1978: 4:103)[14]

- “Began to open Vistos throw the Pine grove on the Banks of H. Hole.”

- Enys, Lt. John, December 1, 1787, describing the mall in Boston, MA (Cometti, ed., 1976: 202)[15]

- “After Dinner we took a walk on the Mall. . . From hence we went to Beacon Hill from whence we had a Charming View of the town and harbour.”

- Enys, Lt. John, January 26, 1788, describing Belvedere, estate of Gov. John Eager Howard, Baltimore, MD (Cometti, ed., 1976: 235)[15]

- “there are some very Charming prospects from some of the Hills, among the rest from the Seat of Colol. Howard which is situated on an eminence but is well coverd by trees from all the cold winds, has a charming View of a Water fall at a Mill, a long Rapid below it, a full View of the town of Baltimore and the Point with the shipping in the harbour, the Bason and all the Small craft, with a very distant prospect down the river towards the Chasapeak Bay. The whole terminated by the surrounding Hills forms a fine Picture.”

- G., L., June 15, [1788], describing The Woodlands, home of William Hamilton, near Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Madsen 1989: 19)[16]

- “[The walks were] planted on each side with the most beautiful & curious flowers & shrubs. They are in some parts enclosed with the Lombardy poplar except here & there openings are left to give you a view of some fine trees or beautiful prospect beyond, & in others, shaded by arbours of the wild grape, or clumps of large trees under which are placed seats where you may rest yourself & enjoy the cool air.”

- Adams, Abigail, 1789, describing Richmond Hill, NY (quoted in Hammond 1982: 179)[17]

- “In front of the house the noble Hudson rolls, his majestic waves bearing upon his bosom innumerable small vessels which are constantly carrying the rich products of the neighboring soil to the busy hand of a more extensive commerce. Beyond the Hudson rises to our view the fertile country of the Jerseys, covered with a golden harvest and pouring forth plenty like the cornucopia of Ceres. On the right hand an extensive plain presents us with a view of fields covered with verdure and pastures full of cattle; on the left, the city opens upon us, intercepted only by clumps of trees and some rising ground. . . If my days of fancy and romance were not past, I could find here an ample field for indulgence.”

- Morse, Jedidiah, 1789, describing Nassau Hall, Princeton, NJ (1789; repr., 1970: 294)[18]

- “Its situation is exceedingly Pleasant and healthful. The view from the college balcony is extensive and charming.”

- Smith, William Loughton, September 8, 1790, describing a house in Albany, NY (1917: 54)[19]

- “I took a walk to General Schyler’s; his house is a large, square brick one, with a flat roof; it stands on a rising ground above the river, and enjoys a commanding view.”

- Bentley, William, October 22, 1790, describing Elias Hasket Derby Farm, Peabody, MA (1962: 1:180)[20]

- “[231] 22. . . The Principal Garden is in three parts divided by an open slat fence painted white, & the fence white washed. It includes 7/8 of an Acre. We ascend from the house two steps in each division. The passages have no gates, only a naked arch with a key stone frame, of wood painted white above 10 feet high. Going into the Garden they look better than in returning, in the latter view they appear from the unequal surface to incline towards the Hill. . . Beyond the Garden is a Spot as large as the Garden which would form an admirable orchard now improved as a Kitchen garden, & has not an ill effect in its present state.”

- Bartram, William, 1791, describing St. Simon’s Island, GA (1928: 72)[21]

- “This delightful habitation was situated in the midst of a spacious grove of Live Oaks and Palms, near the strand of the bay, commanding a view of the inlet.”

- Smith, William Loughton, April 23, 1791, describing Mount Vernon, plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (1917: 63)[19]

- “the view extends up and down the river a considerable distance, the river is about two miles wide, and the opposite shore is beautiful, as is the country along the river. . . embracing the magnificence of the river with the vessels sailing about; the verdant fields, woods, and parks.”

- Spooner, Rev. John Jones, 1793, describing May-cox Plantation, estate of David Meade, Prince George’s County, VA (1923: 8)[22]

- “These grounds contain about twelve acres, laid out on the banks of the James river, in a most beautiful and enchanting manner. Forest and fruit trees are here arranged, as if nature and art had conspired together to strike the eye most agreeably. Beautiful vistas, which open as many pleasing views of the river; the land thrown into many artificial hollows or gentle swellings, with the pleasing verdure of the turf; and the complete order in which the whole is preserved, altogether tend to form it one of the most delightful rural seats that is to be met with in the United States, and do honour to the taste and skill of the proprietor, who was also the architect.”

- La Rochefoucauld Liancourt, François Alexandre-Frédéric, duc de, 1795–97, describing Pottsgrove, PA (1799: 1:35)[23]

- “The landscape is beautiful along this road, abounding with a great variety of fine views, wonderfully enlivened by the verdure of the cornfields and meadows. . . If agriculture were better understood in these parts; if the fields were well mowed and well fenced; and if some trees had been left standing in the middle or on the borders of meadows, the most beautiful parts of Europe could not be more pleasing.”

- Twining, Thomas, May 7, 1795, describing Belvedere, estate of Gov. John Eager Howard, Baltimore, MD (1894: 115)[24]

- “Situated upon the verge of the descent upon which Baltimore stands, its grounds formed a beatiful slant toward the Chesapeak. From the taste with which they were laid out, it would seem that America already possessed a Haverfield or a Repton. The spot, thus indebted to nature and judiciously embellished, was as enchanting within its own proper limits as in the fine view which extended far beyond them. The foreground presented luxurious shrubberies and sloping lawns: the distance, the line of the Patapsco, and the country bordering on Chesapeak Bay.”

- Brown, Charles Brockden, 1798, describing the fictional estate of Wieland, near Philadelphia, PA (1798: 58–59)[25]

- “One sunny afternoon, I was standing in the door of my house, when I marked a person passing close to the edge of the bank that was in front. . .

- “such figures were seldom seen by me, except on the road or field. This lawn was only traversed by men whose views were directed to the pleasures of the walk, or the grandeur of the scenery.”

- Latrobe, Benjamin Henry, 1798, describing the countryside of Virginia (1977: 473–75)[26]

- “When you stand upon the summit of a hill, and see an extensive country of woods and fields without interruption spread before you, you look at it with pleasure. On the Virginia rivers there are a thousand such positions. But this pleasure is perhaps very much derived from a sort of consciousness of superiority of position to all the monotony below you. But turn yourself so as to include in your view a wide expanse of Water, contrasting by its cool blue surface, the waving, and many colored carpet of the Earth, your pleasure is immediately doubled, or rather a new and much greater pleasure arises. An historical effect is produced. The trade and the cultivation of the country croud [sic] into the mind, the imagination runs up the invisible creeks, and visits the half seen habitations. A thousand circumstances are fancied which are not beheld, and the indications of what probably exists, give the pleasure which its view would afford. Having satiated your eye with this prospect, retire within the Grove, so that the foreground shall consist of trees, and shadowy earth. The landscape is immediately lightened up with a thousand new beauties, arising from the novelty of the Contrast. This particular effect, of seeing a distant view glittering among near objects is familiar to every observer. The Landscape is now become a perfect composition.”

- Anonymous, October 2, 1798, describing a property for sale in Spotsylvania County, VA (Virginia Herald)

- “The improvements on it are, a comfortable dwelling house, with all necessary out houses, situated on a beautiful eminence, commanding a view of the greater part of the lower ground.”

- Ogden, John Cosens, 1800, describing Nazareth, PA (1800: 45)

- “From the top of this house [recitation room and Inspector’s study], we were entertained with picture-like views in every direction.”

- Thornton, Anna Maria Brodeau, September 22, 1802, describing Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, VA (Library of Congress, Papers of Anna Maria Brodeau, 1793–1863)

- “The House is situated on the very summit of the mountain, on a circular level, formed by art, commanding a view of all the surrounding country, the small town of Charlottesville and a little winding river. . . with a view of the blue ridge & even more distant mountains form a beautiful scene on the north side of the house.—There is something grand & awful in the situation but far from convenient or in my opinion agreeable—it is a place you wo’d rather look at now & then than live at.”

- Anonymous, February 18, 1803, describing a property for sale in Orange County, VA (Virginia Herald)

- “There is a convenient dwelling house and other out houses, fixed on an elevated situation and commands a beautiful view of the mountains and of the lower country, which added to the health and agreeableness of the neighbourhood, renders the place truly desirable.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, 1804, describing Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, VA (Massachusetts Historical Society, Jefferson Papers)

- “Vistas to very interesting objects may be permitted, but in general it is better so to arrange the thickets as that they may have the effect of vista in various directions. . .

- “the ground between the upper & lower roundabouts to be laid out in lawns & clumps of trees, the lawns opening so as to give advantageous catches of prospect to the upper roundabout.

- “Vistas from the lower roundabout to good portions of prospect.”

- Caldwell, John Edwards, 1808, describing Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, VA (1951: 38–39)[27]

- “The roofs of the passages, and range of buildings, form an agreeable walk, being flat and floored, and are to have a Chinese railing round them; they rise but a little height above the lawn, that they may not obstruct the view.”

- Martin, William Dickinson, May 20, 1809, describing The Woodlands, seat of William Hamilton, near Philadelphia, PA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “If thus far the eye has been pleased from viewing these fine productions of art, how much more will it be gratified when contemplating the prospect that bursts upon the sight from the Centre of the Saloon! The verdant meadow, the spacious lawn, [the] Schuylkill's lucid stream, the floating bridge, the waves here checked by the projecting rock, then overshadowed by inclining trees, until, by meandering in luxuriant folds, the winding waters lead the entranced eye to Delaware’s proud river, on whose swollen bosom rich merchant ships are seen. . . Such are in part, the beauties of this delightful scenery, & had the view terminated with highlands or some o’er-towering mountain, no prospect could have been more perfect.”

- Peale, Charles Willson, 1810, describing Belfield, estate of Charles Willson Peale, Germantown, PA (quoted in Miller and Ward 1991: 54)[28]

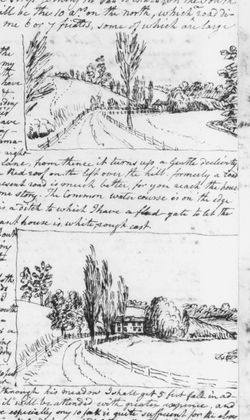

- “In this view imagine that you see a beautiful Meadow on the right. The Tennants House seems to terminate the lane, from thence it turns up a Gentle declivity to the Mansian, of which you see the Top of a Red roof on the left over the hill. formerly a road went over this hill at the dotted lines.” [Fig. 9]

- Gerry, Elbridge, Jr., July 1813, describing Mount Vernon, plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (1927: 174)[29]

- “Back of the mansion is a summer house, which commands an elegant view of the Potomac.” [Fig. 10]

- Gerry, Elbridge, Jr., July 1813, describing the White House, Washington, DC (1927: 180–81)[29]

- “A door opens at each end, one into the hall, and opposite, one into the terrace, from whence you have an elegant view of all the rivers &c.”

- Peale, Charles Willson, November 22, 815, in a letter to his daughter, Angelica Peale, describing Belfield, estate of Charles Willson Peale, Germantown, PA (quoted in Rudnytzky 1986: 43)[30]

- “I have also painted. . . a tolerable large Landscape almost finished, it is a View of the Garden and most of the Buildings, as seen from what we call my seat in the Walk to the mill,—difficult part in it, that is, a representation of the down hill or rather Valley between the point of sight and the Garden—

- “The whole comprehending a tolerable handsome View, including Trees of various folliages— But what must render this Picture more interesting, will be some Portraits setting on the Bench under a Beach Tree, (as yet a Small Tree) but being the nearest object, it must be most distinctly finished, The declining Meadow will form a charming background for the figures on the Bench. There should also be figures in various parts of the Ground to give animation to the sciene, all of which are yet to be done. I intend it for the Museum when finished to my mind I wish I could have you as one of the figure on the Bench.”

- Peale, Charles Willson, August 4, 1816, in a letter to his son, Rembrandt Peale, describing Belfield, estate of Charles Willson Peale, Germantown, PA (quoted in Rudnytzky 1986: 44)[30]

- “I have been so long neglecting the view I am about in [the] garden that the trees & shrubbery have grown so high that I cannot represent them truly without almost totally hiding the walks, therefore I shall prefer leaving out many of them—and also make them smaller.”

- Forman, Martha Ogle, April 29, 1819, describing Rose Hill, home of Martha Ogle Forman, Baltimore County, MD (1976: 80)[31]

- “I have never seen Rose Hill look more beautiful. When the cherry trees on the lawn are in full bloom, and the Apple trees unfolding their lovely blossoms, it forms a most pleasing view of nature.”

- Silliman, Benjamin, 1824, describing Monte Video, property of Daniel Wadsworth, Avon, CT (1824: 12–15)[32]

- “From this place [the summit] you have a view of the lake, of the boat at anchor on its surface, gay with its streamers and snowy awning: of the white building at the north extremity of the water, and, (rising immediately above it,) of forest trees and bold rocks, intermingled with each other, and surmounted by the Tower. . .

- “Along this road the house, the tower, the lake, &c. occasionally appear and disappear, through the openings in the trees; in some parts of it, all these objects are shut from your view; and in no part is the distant view seen, until passing through the last group of shrubbery near the house, you suddenly find yourself within a few yards of the brow of the mountain, and the valey with all its distinct minuteness, immediately below, where every object is as perfectly visible, as if placed upon a map. . .

- “Everything in this view, is calculated to make an impression of the most entire seclusion; for, beyond the water, and the open ground in the immediate neighbourhood of the house, rocks and forests alone meet the eye, and appear to separate you from all the rest of the world. But at the same moment that you are contemplating this picture of the deepest solitude, you may without leaving your place, merely by changing your position, see through one of the long Gothic windows of the same room, which reach to a level with the turf, the glowing western valley, one vast sheet of cultivation, filled with inhabitants, and so near, that with the aid only of a common spy-glass, you distinguish the motions of every individual who is abroad in the neighbouring village, even to the frolicks [sic] of the children, and the active industry of the domestic fowls, seeking their food, or watching over, and providing for their young. From the same window also, when the morning mist, shrouding the world below and frequently hiding it completely from view, still leaves the summit of the mountain in clear sunshine, you may hear through the dense medium, the mingled sounds, occasioned by preparation for the rural occupations of the day.

- “The other branch of the path, after leaving the defile, passes to the east side of the northern ridge, and thence you ascend through the woods, to its summit, where it terminates at the Tower, standing within a few rods of the edge of the precipice. The tower is a hexagon, of sixteen feet diameter, and fifty-five feet high; the ascent, of about eighty steps, on the inside, is easy, and from the top which is nine hundred and sixty feet above the level of Connecticut river, you have at one view, all those objects which have been seen separately from the different stations below. The diameter of the view in two directions, is more than ninety miles, extending into the neighbouring states of Massachusetts and New-York, and comprising the spires of more than thirty of the nearest towns and villages.”

- Coolidge, Ellen Wayles Randolph, 1825, describing Mount Holyoke, MA (quoted in Lockwood 1931: 1:109)[33]

- “From the top of Mount Holyoke, which commands, perhaps, one of the most extensive views in these States, the whole country, as you look down upon it resembles one vast garden divided into parterres.”

- Sheldon, John P., December 10, 1825, describing Fairmount Waterworks, Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Gibson 1988: 5)[34]

- “Delightful seats, surrounded by various kinds of trees and shrubbery, with gardens containing summer houses, vistas, embowered walks, &c meet your view in almost every direction, woods sloping gently to the river’s edge, by the side of smooth lawns, add to the pleasing variety of the scene; and the Schuylkill, with its noble dam and bridges serves as a most beautiful finish to the foreground.”

- Smith, Margaret Bayard, August 17, 1828, describing Montpelier, plantation of James Madison, Montpelier Station, VA (1906: 233)[35]

- “We were at first conducted into the Drawing room, which opens on the back Portico and thus commands a view through the whole house, which is surrounded with an extensive lawn, as green as in spring; the lawn is enclosed with fine trees, chiefly forest, but interspersed with weeping willows and other ornamental trees, all of most luxuriant growth and vivid verdure. It was a beautiful scene!”

- Thacher, James, December 3, 1830, describing Hyde Park, seat of David Hosack, on the Hudson River, NY (New England Farmer 9: 156)[36]

- “From the piazza, and from the bank on the west side of the house we have a charming view, extending to the opposite side of the river, of the blue summits of the Catskill mountains, and many gentlemen’s seats, and cultivated farms.”

- Breck, Joseph, February 1, 1836, describing Bellmont Place, residence of John Perkins Cushing, Watertown, MA (Horticultural Register 2: 43)[37]

- “The approach to the mansion from the road is by a winding avenue through a fine grove of ancient deciduous trees. The first view of the garden and ranges of glass structure, as we emerged from the grove, was truly magnificent.”

- Lyell, Sir Charles, 1846, describing Natchez, MS (1849: 2:153)[38]

- “Many of the country-houses in the neighborhood are elegant, and some of the gardens belonging to them laid out in the English, others in the French style. In the latter are seen terraces, with statues and cut evergreens, straight walks with borders of flowers, terminated by views into the wild forest, the charms of both being heightened by contrast. Some of the hedges are made of that beautiful North American plant, the Gardenia, miscalled in England the Cape jessamine, others of the Cherokee rose, with its bright and shining leaves.”

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1850, describing Baltimore, MD (1850: 332–33)[39]

- “856. Public Gardens. . .

- “At Baltimore, the public walk is along a fine terrace belonging to a fort nobly situated on the Patapsco, and commanding the approach from Chesapeake Bay, and a magnificent view of the city and river. . .” [40]

Citations

- Dezallier d’Argenville, Antoine-Joseph, 1712, The Theory and Practice of Gardening (1712; repr., 1969: 13)[41]

- “THE fourth Thing required in a good Situation, is, the View and Prospect of a fine Country.”

- Gibbs, James, 1728, A Book of Architecture (1728: xviii–xix)[42]

- “A Pavillion design’d for Sir John Curzon for his Seat near Derby. It is a Cube of 20 feet, adorn’d with three Venetian Windows, circular Niches for Busto’s [sic], and an Entablature supported by Rustick Coines. There were two of them to have been built opposite to one another, on each side of a Vista proposed to be cut through a Wood, and to be terminated with an Obelisk upon a Hill fronting the House; the execution of which was prevented by Sir John’s Death.”

- Langley, Batty, 1728, New Principles of Gardening (1728; repr., 1982: 195)[43]

- “General DIRECTIONS, &c.. . .

- “III. That Views in Gardens be as extensive as possible.

- “IV. That such Walks, whose Views cannot be extended, terminate in Woods, Forests, mishapen Rocks, strange Precipices, Mountains, old Ruins, grand Buildings, &c.”

- Chambers, Ephraim, 1741–43, Cyclopaedia (1741: 1:n.p.)[44]

- “GLADE, in agriculture, gardening, &c.a vista, or open and light passage, made through a thick wood, grove, or the like; by lopping off the branches of trees along the way. See AVENUE, GROVE, &c.”

- Ware, Isaac, 1756, A Complete Body of Architecture (1756: 639–41)[45]

- “THE buildings admitted into gardens may be arranged under two general heads; those which are erected as objects in themselves, and those from which prospects and other objects are to be viewed. The first are the principal in their nature and purpose: they require elegance, and the eye expects something in them worthy to detain its attention. The places for these in a good garden are to be variously chosen; on eminences, or in shadowy scenes: to terminate the view as objects, or to surprise the unexpecting eye in a recess of contemplation. We have observed that in many places views are to be closed; as where the nature of the ground requires it; or where an unpleasing prospect or object is to be shut out: the seat, building, temple, or whatsoever name or rank its form or bigness give it, is to be accommodated to all these considerations. Where the sole intent is to admit a prospect, and give repose after walking, the form may be plain and simple, convenient and unornamented. . .

- “When a garden is already made in an ill spot, all that can be done is to open agreeable views by clearing away walls and hedges in the ground; and trees, and sometimes even buildings, when ill-placed, ill-looking and of little value: this is to be done when something pleasing, some view of elegant, wild nature can be let in; and where that cannot be, some pavilion, such as we have described, or shall describe, must shut out unalterable deformity.”

- Sheridan, Thomas, 1789, A Complete Dictionary of the English Language (n.p.)[46]

- “VIEW, vu’. s. Prospect; sight, power of beholding; act of seeing; sight, eye; survey, examination by the eye; intellectual survey; space that may be taken in by the eye, reach of sight; appearance, show; display, exhibition to the sight or mind; prospect of interest; intention, design.”

- Marshall, William, 1803, On Planting and Rural Ornament (1:260, 263)[47]

- “THE WALK, in extensive grounds, is as necessary as the Fence. The beauties of the place are disclosed that they may be seen; and it is the office of the walk to lead the eye from view to view. . .

- “THE direction of the walk ought to be guided by the points of view to which it leads. . .

- “SEATS have a two-fold use; they are useful as places of rest and conversation, and as guides to the points of view, in which the beauties of the surrounding scene are disclosed. Every point of view should be marked with a seat, and, speaking generally, no seat, ought to appear, but in some favourable point of view.”

- Repton, Humphry, 1803, Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1803: 74 and 153)[48]

- “it is hardly possible to convey an adequate and distinct idea of those numerous objects so wonderfully combined in this extensive view; the house, the church, the lawns, the woods, the bold promontory of Beechy Head, and the distant plains bounded by the sea, are all collected in one splendid picture, without being crowded into confusion.

- “This view is a perfect landscape, while that from the tower is rather a prospect; it is of such a nature as not to be well represented by painting; because its excellence depends upon a state of atmosphere, which is very hostile to the painter’s art. . .

- “Yet the summit of a naked brow, commanding views in every direction, may require a covered seat or pavilion; for such a situation, where an architectural building is proper, a circular temple with a dome, such as the temple of the Sybils, or that of Tivoli, is best calculated.”

- M’Mahon, Bernard, 1806, The American Gardener’s Calendar (1806: 100)[49]

- “THE Kitchen-garden is a principal district of garden-ground allotted for the culture of all kinds of esculent herbs and roots for culinary purposes, &c. . . .

- “As to the situation of this garden, with respect to the other districts. . . it should generally be placed detached entirely from the pleasure-ground; also as much out of view of the front of the habitation as possible, at some reasonable distance, either behind it, or towards either side thereof, so as its walls or other fences may not obstruct any desirable prospect either of the pleasure-garden, fields, or the adjacent country.”

- [Abercrombie, John, with James Mean, 1817, Abercrombie’s Practical Gardener (1817: 472)[50]

- “The view FROM the house, and TO the house, cannot always be consulted with mutual improvement. When a high terrace with ornaments which appear to mark the boundary of the architect’s province, is interposed between the house and the lawn, the view immediately under the windows cannot certainly be so pleasant as if the house stood in a verdant field:—but let the prospect be reversed, and every stranger will see more grandeur in the house connected by a terrace with the garden; and perhaps among the spectators under the influence of cultivated taste, a few may think such a gradation conduces to general harmony.”

- Nicol, Walter, 1823, The Villa-Garden Directory (1823: 4–5)[51]

- “Next to the error of rearing high fences, is that of bounding the whole premises by a close and connected belt of shrubbery. . .

- “from no point can a view of distant objects be had, without being interrupted by this edging; which is perplexing to the eye, in a great measure, although the situation of the house may be such as to admit of looking over it.

- “Instead of this formal belt or edging, a few festoons or groups of various dimensions, being hung on the outer fence, with intervening single trees, sometimes pretty close to the groups, and sometimes more detached, so as to form irregular vistas, would be more airy, and also more in character here.”

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828: n.p.)[52]

- “VIEW, n. vu. Prospect; sight; reach of the eye. . .

- “2. The whole extent seen. . .

- “3. Sight; power of seeing, or limit of sight. . .

- “4. Intellectual or mental sight. . .

- “5. Act of seeing. . .

- “6. Sight; eye. . .

- “7. Survey; inspection; . . .

- “9. Appearance; show. . .

- “10. Display; . . .

- “11. Prospect of interest.”

- Anonymous, April 1, 1837, “Landscape Gardening” (Horticultural Register 3: 127–28, 130)[53]

- “In forming plantations of trees and shrubs, so as to produce a pleasing landscape effect, few rules can be given which would apply generally. . .

- “In grounds of any considerable extent, the view of the whole should never be taken in at once; but it should be so divided into different scenes or compartments, which may be bounded by trees, that only a small part is visible at first to the spectator; but as he advances new and varied prospects open upon him, so that he is agreeably surprised to find, that what at first seemed to terminate his view, only served to introduce him to new beauties. . .

- “At favorable points, and those only, should the view be left open for more distant scenes. Sometimes by a judicious arrangement, the same objects seen from different places, may be made to present quite different aspects by appearing to group differently. The walk should be so directed as not to exhibit these views except at the most advantageous points. A bend in a walk should always exist from some cause either real or apparent. . .

- “If it [the house] is situated on an eminence, the back as well as front view may be exhibited to great advantage, and the effect will be heightened if a view of water can be then enjoyed. Limited prospects and neighboring buildings not worthy of notice, may be concealed by plantations of trees. The appearance of distance may be increased by planting trees of dark green and large dense foliage on the foreground, and those of light and airy foliage in the distance; this will produce the same effect as shades in a landscape picture. Trees and shrubs in front of the house should be planted and pruned so as to present a chaste and neat appearance; imitations, therefore, of the wilder scenes of nature, such as rocks, cascades, old trees, and festoons of climbing plants, should be situated back and more remote.”

- Elliott, Charles Wyllys, October 1848, “Reviews: Cottages and Cottage Life” (Horticulturist 3: 181)[54]

- “To command a view—to have the advantage of shade, and shelter, and water—to have the barn and out-buildings near, yet not conspicuous; to permit of easy drainage from the cellar, if it is necessary; to be easy of access from the highway; these are to be considered.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1849, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849; repr., 1991: 113–14)[55]

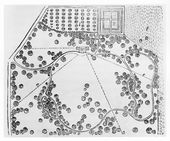

- “a ground plan of the place is given, as it would appear after having been judiciously laid out and planted, with several years’ growth. . . It will be seen here, that one of the largest masses of wood forms a background to the house, concealing also the outbuildings; while, from the windows of the mansion itself, the trees are arranged so as to group in the most pleasing and effective manner; at the same time broad masses of turf meet the eye, and fine distant views are had through the vistas in the lines e e.” [Fig. 11]

- Webster, Noah, 1850, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1850: 1239)[56]

- “VIS’TA, n. [It., sight; from L. visus, video.]

- “A view or prospect through an avenue, as between rows of trees; hence, the trees or other things that form the avenue.

- “The finished garden to the view

- “Its vistas opens and its alleys green. Thomson.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, March 1850, “How to Arrange Country Places” (Horticulturist 4: 396)[57]

- “The first principle in ornamental planting, is to study the character of the place to be improved, and to plant in accordance with it. If your place has breadth, and simplicity, and fine open views, plant in groups, and rather sparingly, so as to heighten and adorn the landscape, not shut out and obstruct the beauty of prospect which nature has placed before your eyes.”

Images

Inscribed

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, View to the North from the Lawn at Mount Vernon, 1796.

Thomas Jefferson, Letter describing plans for a “Garden Olitory,” c. 1804.

J. C. Loudon, In planting with a view to natural beauty, in An Encyclopædia of Gardening, 4th ed. (1826), 1008, fig. 691.

Anonymous, “View of Mount Auburn,” in American Magazine of Useful and Entertaining Knowledge 2, no. 6 (February 1836): 234.

Robert Mills, Picturesque View of the Building, and Grounds in front, 1841.

Alexander Jackson Davis, View N. W. at Blithewood, c. 1841.

Anonymous, “View in the Grounds at Hyde Park,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), pl. opp. 45, fig. 1.

Anonymous, “Plan of the foregoing grounds as a Country Seat, after ten years’ improvement,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), 114, fig. 24. Downing notes with dotted lines that “fine distant views are had through the vistas in the lines e e.”

James Smillie and E. G. Dunnel (engraver), “View from Mount Auburn, Mount Auburn Cemetery,” in Cornelia W. Walter, Mount Auburn Illustrated (1847; repr., 1850), opp. 112.

Associated

Anna Peale Sellers, after Charles Willson Peale, Belfield Farm, Germantown, PA, Late 19th century.

Alexander Jackson Davis, From Montgomery Pl. looking up river, n.d.

George Isham Parkyns, Mount Vernon, 1795.

Alexander Robertson (artist), Francis Jukes (engraver), “Mount Vernon in Virginia,” 1800.

George Ropes, Mount Vernon, 1806.

Charles Willson Peale, Sketches of Belfield, 1810.

John T. Bowen, A View of the Fairmount Water-Works with Schuylkill in the distance, taken from the Mount, 1838.

W. Mason, “Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane,” c. 1841, in Thomas S. Kirkbride, Reports of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane: With a Sketch of Its History, Buildings, and Organization (1851), frontispiece.

Anonymous, “Front View of the Mansion at Mount Vernon,” in Franklin Knight, ed., Letters on agriculture from His Excellency George Washington. . . (1847), opp. 14.

Anonymous, “Cottage Residence of Wm. H. Aspinwall, Esq.,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), pl. opp. 51, fig. 8.

Attributed

Alexander Jackson Davis, Montgomery Place—Shore Seat, n.d., drawing. The Alexander Jackson Davis Sketchbook, c. 1830–50.

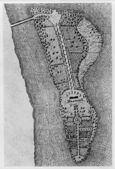

Batty Langley, “Design of a Garden and Wilderness in an Island,” in New Principles of Gardening (1728), pl. XV.

Charles Willson Peale, William Paca, 1772.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, View of Mount Vernon looking towards the South West, 1796.

Charles Fraser, Rice Hope, c. 1803.

Anonymous, Vignette of contrasting garden styles, in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849), p. 17.

George Hayward after J. Anderson, View of The Belvedere Club House, 1794, 1828.

Notes

- ↑ For an example of the significance of the construction of views in landscape perception see Peter M. Briggs, “Timothy Dwight ‘Composes’ a Landscape for New England,” American Quarterly 40 (September 1988): 359–77, view on Zotero. For a discussion of the links between optics, monumental architecture and landscapes, and social control, see Jerry D. Moore, Architecture and Power in the Ancient Andes (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 98–101 and 168–73, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Trumbull describing his plan for Yale College, New Haven, Connecticut. Yale University Library, Manuscripts and Archives, Yale Picture Collection, 48-A-46, box 1, folder 2.

- ↑ Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe, “Vista,” in Oxford Companion to Gardens, ed. Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe et al. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), 590, view on Zotero.

- ↑ For an example of the design practices used in creating views and prospects in eighteenth-century English gardens, see Douglas Chambers, “Prospects and the Natural Beauties of Places: Joseph Spence,” in The Planters of the English Landscape Garden (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1993), 164–76, view on Zotero. For a discussion of changing land-use practices and their implications on the organization of sight in landscape gardening, see Denis E. Cosgrove, Social Formation and Symbolic Landscape (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984), 189–222, view on Zotero; Raymond Williams, The Country and the City (London: Palladin, 1973) view on Zotero; Simon Pugh, ed., Reading Landscape: Country, City, Capital (Manchester, England: Manchester University Press, 1990), view on Zotero, including the essay by John Barrell, “The Public Prospect and the Private View: the Politics of Taste in Eighteenth-Century Britain,” 19–40, view on Zotero.

- ↑ For a fuller discussion of the villa in the New World, see James Ackerman, The Villa: Form and Ideology of Country Houses (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Elizabeth Kryder-Reid, “The Archaeology of Vision in Eighteenth-Century Chesapeake Gardens,” Journal of Garden History 14 (Spring 1994): 42–54, view on Zotero, and Kryder-Reid, “Sites of Power and the Power of Sight: Vision in the California Mission Landscape,” in Dianne Harris and D. Fairchild Ruggles, Sites Unseen: Landscape and Vision (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2007), 181–212, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Dell Upton, Holy Things and Profane: Anglican Parish Churches in Colonial Virginia (New York: Architectural History Foundation and Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1986), view on Zotero, and “White and Black Landscapes in Eighteenth-Century Virginia,” in Material Culture in America, 1600–1860, ed. Robert Blair St. George (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1988), 357–69, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Peter Martin, The Pleasure Gardens of Virginia: From Jamestown to Jefferson (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Hannah Callender Sansom, The Diary of Hannah Callender Sansom: Sense and Sensibility in the Age of the American Revolution, ed. Susan E. Klepp and Karin Wulf (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2010), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Eddis, Letters from America: Historical and Descriptive; Compromising Occurances from 1769 to 1777 Inclusive (London: Printed for the author, 1792), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson, The Garden Book, ed. by Edwin M. Betts (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1944), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Anburey, Travels through the Interior Parts of America, 2 vols. (1789; repr., New York: New York Times and Arno Press, 1969), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Lee Shippen, Westover Described in 1783: A Letter and Drawing Sent by Thomas Lee Shippen, Student of Law in Williamsburg, to His Parents in Philadelphia (Richmond, VA: William Byrd Press, 1952), view on Zotero.

- ↑ George Washington, The Diaries of George Washington, ed. by Donald Jackson and Dorothy Twohig, 6 vols. (Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 1978), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Elizabeth Cometti, ed., The American Journals of Lt. John Enys (Syracuse, NY: Adirondack Museum and Syracuse University Press, 1976), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Karen Madsen, “To Make His Country Smile: William Hamilton’s Woodlands,” Arnoldia 49 (1989): 14–23, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Arthur Hammond, “‘Where the Arts and the Virtues Unite’: Country Life Near Boston, 1637–1864” (PhD diss., Boston University, 1982), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jedidiah Morse, The American Geography; Or, A View of the Present Situation of the United States of America (Elizabeth Town, NJ: Shepard Kollock, 1789), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 William Loughton Smith, Journal of William Loughton Smith, 1790–1791, ed. by Albert Matthews (Cambridge, MA: The University Press, 1917), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Bentley, The Diary of William Bentley, D.D., Pastor of the East Church, Salem, Massachusetts (Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1962), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Bartram, Travels through North and South Carolina, Georgia, East and West Florida, ed. by Mark Van Doren (New York: Dover, 1928), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Jones Spooner, “A Topographical Description of the County of Prince George in Virginia, 1793,” Tyler’s Quarterly Historical and Genealogical Magazine 5 (1923): 1–11, view on Zotero.

- ↑ François-Alexandre-Frédéric, duc de La Rochefoucauld Liancourt, Travels through the United States of North America, the Country of the Iroquois, and Upper Canada, in the Years 1795, 1796, and 1797, ed. by Brisson Dupont and Charles Ponges, trans. by H. Newman, 2nd ed., 4 vols. (London: R. Philips, 1800), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Twining, Travels in America 100 Years Ago (New York: Harper, 1894) view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Brockden Brown, Wieland, or The Transformation, An American Tale (New York: T. & J. Swords, 1798), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Benjamin Henry Latrobe, The Virginia Journals of Benjamin Henry Latrobe, 1795–1798, ed. by Edward C. Carter II, 2 vols. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1977), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Edwards Caldwell, A Tour through Part of Virginia, in the Summer of 1808; Also, Some Account of the Islands of the Azores, ed. by William M. E. Rachal (Richmond, Va.: Dietz, 1951), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Lillian B. Miller and David C. Ward, eds., New Perspectives on Charles Willson Peale (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press for the Smithsonian Institution, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Elbridge Gerry Jr., The Diary of Elbridge Gerry Jr. (New York: Brentano’s, 1927), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Kateryna A. Rudnytzky, “The Union of Landscape and Art: Peale’s Garden at Belfield” (Honors thesis, LaSalle University, 1986), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Martha Ogle Forman, Plantation Life at Rose Hill: The Diaries of Martha Ogle Forman, 1814–1845 (Wilmington, DE: Historical Society of Delaware, 1976), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Benjamin Silliman, Remarks Made on a Short Tour between Hartford and Quebec, in the Autumn of 1819 (New Haven, CT: S. Converse, 1824), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alice B. Lockwood, ed., Gardens of Colony and State: Gardens and Gardeners of the American Colonies and of the Republic before 1840, 2 vols. (New York: Charles Scribner’s for the Garden Club of America, 1931), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jane Mork Gibson,“‘The Fairmount Waterworks,” Bulletin, Philadelphia Museum of Art 84 (1988): 5–40, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Margaret Bayard Smith, The First Forty Years of Washington Society, ed. by Gaillard Hunt (New York: Charles Scribner’s, 1906), view on Zotero.

- ↑ James Thacher, “An Excursion on the Hudson. Letter II,” New England Farmer, and Horticultural Journal 9, no. 20 (December 3, 1830): 156–57, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Joseph Breck, “Gardens, Hot-Houses, &c., in the Vicinity of Boston,” Horticultural Register, and Gardener’s Magazine 2 (February 1, 1836): 41–47, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Sir Charles Lyell, A Second Visit to the United States of North America, 2 vols. (New York: Harper, 1849), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, new ed., corr. and improved (London: Longman et al., 1850), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Loudon 1850, vol. II, 303.

- ↑ A.-J. (Antoine Joseph) Dezallier d’Argenville, The Theory and Practice of Gardening; Wherein Is Fully Handled All That Relates to Fine Gardens, . . . Containing Divers Plans, and General Dispositions of Gardens; . . . , trans. by John James (London: Geo. James, 1712), view on Zotero.

- ↑ James Gibbs, A Book of Architecture, Containing Designs of Buildings and Ornaments (London: Printed for W. Innys et al., 1728), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Batty Langley, New Principles of Gardening, or The Laying out and Planting Parterres, Groves, Wildernesses, Labyrinths, Avenues, Parks, &c. (London: A. Bettesworth and J. Batley, etc.,1728; repr., London: Garland: 1982), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Ephraim Chambers, Cyclopaedia, or An Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences. . . ., 5th ed., 2 vols. (London: D. Midwinter et al., 1741), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Isaac Ware, A Complete Body of Architecture (London: T. Osborne and J. Shipton, 1756), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas A. Sheridan, A Complete Dictionary of the English Language, Carefully Revised and Corrected by John Andrews. . . , 5th ed. (Philadelphia: William Young, 1789), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Marshall, On Planting and Rural Ornament: A Practical Treatise. . . , 2 vols. (London: G. and W. Nicol, G. and J. Robinson, T. Cadell, and W. Davies, 1803), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Humphry Repton, Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (London: Printed by T. Bensley for J. Taylor, 1803), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bernard M’Mahon, The American Gardener’s Calendar: Adapted to the Climates and Seasons of the United States. Containing a Complete Account of All the Work Necessary to Be Done. . . for Every Month of the Year. . . (Philadelphia: Printed by B. Graves for the author, 1806), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Abercrombie, Abercrombie’s Practical Gardener Or, Improved System of Modern Horticulture (London: T. Cadell and W. Davies, 1817), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Walter Nicol, The Villa-Garden Directory, or Monthly Index of Word, to Be Done in Town and Villa Gardens, Shrubberies and Parterres (Edinburgh: Archibald Constable, 1823), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, “Landscape Gardening,” Horticultural Register, and Gardener’s Magazine 3 (April 1, 1837): 121–31, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Wyllys Elliott, “Reviews: Cottages and Cottage Life,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 3, no. 4 (October 1848): 179–82, view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America, 4th ed. (1849; repr., Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language (Springfield, MA: George and Charles Merriam, 1850), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. Downing, “How to Arrange Country Places,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 4, no. 9 (March 1850): 393–96, view on Zotero.