Alexander Garden

Overview

Birth Date: January 1730

Death Date: April 15, 1791

Role: Naturalist

Used Keywords: Arbor, Border, Canal, Grove, Lawn, Meadow, Parterre, Piazza, Picturesque, Pond, Prospect, Thicket, Walk

Other resources: Library of Congress Authority File; American National Biography Online; Historic Charleston Foundation - Broad Street Residence;

Alexander Garden (January 1730–April 15, 1791), a Scottish-born physician and naturalist, lived for many years in Charleston, South Carolina, where he pursued horticultural experiments in the garden of his town house and at his country estate, Otranto. Garden discovered several new genera of plants, and engaged in plant and seed exchanges with prominent botanists and plant dealers in Europe and America. The flowering shrub Gardenia was named in his honor.

History

While studying at Marischal College, Aberdeen, from 1743 to 1746, Alexander Garden served as an apprentice to Dr. James Gordon, professor of medicine, who introduced him to botanical studies and “tinctured my mind with a relish for them.”[1] He continued his study of botany while pursuing a medical degree at the University of Edinburgh, working under Charles Alston (1675–1760), professor of botany and medicine, as well as Keeper of the Garden at Holyrood and King’s Botanist.[2] Garden later recalled: “I then & even to this day remember every Genus nay Every Species that is either in the King’s Garden or in the Physic Garden. I could go to the very spot where it grows.”[3] In search of professional opportunities and a warmer climate, Garden set out in 1751 for South Carolina, apparently stopping at Lisbon, where he purchased a four-volume Italian translation of Francesco Eulaio Savastano’s botanical treatise, Botanicorum seu institutionum rei herbariae (Naples, 1712), which he brought to America along with Alston’s catalogue of the Edinburgh Garden.[4] Within days of his arrival in Charles Town (modern-day Charleston), Garden began sending indigenous plants to colleagues across the Atlantic—a practice he sustained over the next decade.[5]

Garden’s contributions to scientific knowledge of American flora became more substantial after a fellow amateur botanist, the Carolina planter and politician William Bull II, lent him several foundational botanical texts, including Carl Linnaeus’s Fundamenta Botanica (1736) and Classes Plantarum (1738), and John Clayton’s Flora Virginica (1739), the first catalogue of plants indigenous to the American South.[6] Guided by Linnaeus’s books, Garden would go on to dissect 1,000 local plants and to write taxonomic descriptions of many.[7] During the summer of 1754 he visited Coldengham, the remote Hudson Highland estate of the Scottish physician and amateur botanist Cadwallader Colden, where he first saw Linnaeus’s Genera Plantarum (1742) and Critica Botanica (1737).[8] Skilled in Linnaeus’s system of plant classification, Colden and his daughter Jane had documented several hundred plants native to their region of New York, and they exchanged plants and seeds with Garden for several years following his visit (view text).[9] Garden took it upon himself to spread news of Jane Colden’s botanical accomplishments to his network of European botanists, and in 1756 he persuaded the Philosophical Society of Edinburgh to publish a new plant she had discovered and offered to name Gardenia in his honor—a tribute disallowed by Linnaeus, who considered the plant a known genus.[10]

While at Coldengham, Garden met the Philadelphia nurseryman John Bartram, who was collecting plants in the area.[11] Garden visited Philadelphia before returning to Carolina and spent several days with Bartram, touring his Botanic Garden and Nursery and combing the surrounding countryside for unusual plants (). Garden continued to collect seeds and plants after returning home despite chronic ill health and the overwhelming demands of his medical practice (which included introducing the first smallpox vaccine to Charles Town). In June 1755 he accompanied the expedition of South Carolina governor James Glen (1701–1777) into the Cherokee territories west of Charles Town, taking advantage of the trip to collect botanical and geological specimens.[12] Hoping to return “richly laden with the spoils of Nature and our Appalachian Mountains,” Garden set out the following year on a still more grueling expedition to the Mississippi River, remarking to a friend, “Good God what will not the Sacred thirst of the Botanic Science urge one to undergo.”[13]

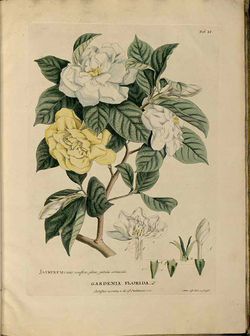

Garden’s direct access to American plants and animals provided botanical insights unavailable to his British and European colleagues. He often disagreed with Linnaeus’s interpretation of American species and genera, and was a particularly harsh critic of Mark Catesby’s Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands. The British merchant and naturalist John Ellis (c. 1710–1776) became Garden’s great champion, forwarding his specimens and notes to Linnaeus, presenting his reports before the Royal Society in London, and arranging for his specimens to be engraved by the botanical artist Georg Dionysius Ehret. Ehret’s Halesia, for example, originated with specimens gathered during the 1755 expedition with Gov. Glen, which Garden sent to Ellis, who forwarded them to Linnaeus.[14] Despite Ellis’s efforts, Linnaeus for several years ignored Garden’s letters and discounted his claims of new finds. Wishing to honor Ellis and his former professor, James Gordon, Garden repeatedly sought permission to confer the names Ellisiana and Gordonia on Carolina plants that he took to be new genera.[15] Ellis returned the favor by pressuring Linnaeus to name a plant Gardenia. In May 1757 he urged him to consider the Beureria, which Ehret had recently engraved based on a specimen provided by Garden [Fig. 1] ().[16] Undeterred when Linnaeus chose the name Calycanthus instead, Ellis tried again in June 1760, suggesting the name Gardenia for an exotic evergreen shrub with fragrant white flowers introduced to England in 1754 () and engraved by Ehret a few years later [Fig. 2]. Linnaeus finally consented to the request, and on November 20, 1760, Ellis presented the Gardenia to the Royal Society ().[17]

Garden’s European correspondents ultimately included several eminent naturalists, among them the Dutch botanist John Frederick Gronovius in Leyden, whom Garden promised to send “anything among the animals, vegetables or minerals which would be pleasing to you.”[18] Through these contacts, Garden received the latest botanical treatises within months of publication, as well as rare books, such as Linnaeus’s Hortus Cliffortianus—one of only two copies in America at that time.[19] As Garden’s correspondence grew, so did his reputation. Toward the end of his life, he was extolled by the English botanist James Edward Smith (1759–1828), founder of the Linnaean Society in London, as “Dr. Garden, to whom Linnaeus was so much obliged in his last edition of the Systema Naturae that I think no name occurs more frequently.”[20]

In the garden of his Broad Street house, Garden propagated the seeds and specimens he obtained through botanical exchanges and expeditions. Contemporary accounts allude to his impressive array of plants and talent for horticulture. His neighbor Martha Daniell Logan, who operated a commercial nursery in Charles Town, begged John Bartram in February 1761 to help her procure some coveted slips “of the Tree you Call the Snowball,” which “Doe very well with us for Doctor Garden has a good many roots Now bluming” (view text). Bartram would have known the plant, for he had been Garden’s guest for nearly three weeks the previous March on his first visit to South Carolina.[21] On their single joint excursion, Garden pointed out indigenous plants unfamiliar to Bartram, who seemed “almost ravished of his senses and lost in astonishment.”[22] Bartram also admired an evergreen growing in his host’s garden, later asking Martha Daniell Logan to send him some of its seeds.[23] Garden made room for specimens Bartram temporarily transplanted and left in his care, including Magnolia tripetala (umbrella tree), Magnolia altissima, Zephyranthes atamasca, and a four-leafed Bignonia. After nursing them for several months, he sent word to Bartram in October 1761, “Your plants in my Garden thrive surprisingly well & they are now ready for your Boxes” (). In return, Bartram sent Garden a large box of plants that included several evergreens (which he identified as Newfoundland Spruce, Hemlock Fir, and Juniper) as well as aromatic herbs (such as Lavender and Fraxinella). Hungry for more, Garden requested a parcel of bulbs (Hyacinth and Narcissus) ().

In addition to pursuing his own botanical and agricultural experiments, Garden encouraged the efforts of his friends and neighbors. He advised Eliza Pinckney on acclimating exotic plants imported from overseas, and persuaded his friends Christopher Gadsden and Henry Middleton to try their hands at cultivating grape vines that the Royal Society sent to Charles Town in 1760.[24] He was familiar with the plants cultivated in other local gardens, and took Bartram on a tour of several, including those of Thomas and Elizabeth Lamboll and Henry Laurens, when the nurseryman again passed through Philadelphia en route to Florida in July 1765.[25] For many years, Garden entertained the hope of establishing a “publick garden” for the experimental cultivation of plants that did not grow in Britain.[26] Despite the endorsement of the Royal Society, he failed to gain local support for the plan, even after reviving it, in 1773, as a cost-efficient alternative to the botanic garden then being proposed for western Florida.[27] By then Garden had acquired Otranto, a 1,689-acre country estate outside of Charles Town. There he laid out gardens and pursued botanical experiments on a grander scale.

Garden’s loyalty to Britain ultimately caused a fatal rift with his adopted country. At the conclusion of the Revolutionary War in 1782, the new American government confiscated Otranto along with his other plantations and property and banished Garden from South Carolina. He returned to Britain in January 1783 where, as North America’s preeminent botanist, he soon became an active and much-honored participant in the activities of the Royal Society.[28] He spent the rest of his life in England, traveling occasionally for reasons of health but never returning to America. In 1789, two years before he died of tuberculosis, he penned a vivid recollection of the colors, smells, and sounds of Otranto in a poignant letter to his friend and countryman, George Ogilvie (view text). Garden’s letter enabled Ogilvie to complete “Carolina; or, The Planter,” an epic poem in the georgic mode that he had begun at his plantation near Charles Town in 1776. The poem described the “situation and occupation of a Carolina Planter,” and the political conflicts threatening to alter the planter’s way of life. Before publishing the poem in 1790, Ogilvie added nearly 200 verses on Otranto, which he described as the ideal of southern plantation life—a haven of intellectual contemplation and natural beauty—by then, a paradise lost (view text).[29]

—Robyn Asleson

Texts

- Garden, Alexander, November 4, 1754, in a letter to Cadwallader Colden, describing John Bartram (Colden 1921: 4:471–72)[30]

- “I have met wt very Little new in the Botanic way unless Your acquaintance Bartram, who is what he is & whose acquaintance alone makes amends for other disappointments in that way. . . One Day he Dragged me out of town & Entertain’d me so agreably with some Elevated Botanicall thoughts, on oaks, Firns, Rocks & c that I forgot I was hungry till we Landed in his house about four Miles from Town. . .

- “His garden is a perfect portraiture of himself, here you meet wt a row of rare plants almost covered over wt weeds, here with a Beautiful Shrub, even Luxuriant Amongst Briars, and in another corner an Elegant & Lofty tree lost in common thicket—on our way from town to his house he carried me to severall rocks & Dens where he shewed me some of his rare plants, which he had brought from the Mountains &c. In a word he disdains to have a garden less than Pensylvania [sic] & Every den is an Arbour, Every run of water, a Canal, & every small level Spot a Parterre, where he nurses up some of his Idol Flowers & cultivates his darling productions. He had many plants whose names he did not know, most or all of which I had seen & knew them—On the other hand he had several I had not seen & some I never heard of.” back up to History

- Alexander Garden, February 18, 1755, in a letter to Cadwallader Colden (Colden 1923: 5:4–5)[31]

- “Some time ago I. . . sent you Some of those seeds you wanted, I hope they will Come all safe to hand in due time—Since that I have had severall Letters from Europe & a pretty parcell of Seeds from Russia from Dr Mounsey cheif Physician to the Army & Physician to the Prince Royal of Russia they are mostly Persian seeds—I have sent a few to Miss Colden which was all that I had time to pack up as the Sloop is just now hauling of[f] from the wharf.

- “By Capt Conyers I sent some few Africain plants & Some natives of Carolina as they were mostly curious shrubs I shall be vastly anxious to hear that they have come safe to you & in proper season; I can warrant the goodness of all those that went by Conyers—I have sent you Some more of the true Indigo seed & some Millet seed which I'm persuaded will both grow very well w[i]t[h] you—I mentioned to Miss Colden that the Small Bags of Shells something like Hops that she has are the reall Matrices of the Buccinum ampullatum of Dr Lister. Some days ago I met w[i]t[h] a very Large parcel on the Beach where I had an opportunity of Examining them,—I need not tell you that any Collection of your Northern seeds will be most acceptable to me as likewise all your Insects, Flies, Dryed Birds &c Especially some heads & Bodies of the Cerva Volans of which I had one head when I had the honour of waiting on you at Coldengham they are a Species of the Lucanus of the order Coleoptera Aloe clytris duobus tectae.—I shall in my next mention to Miss Colden the method of preserving Butterflies &cccc.” back up to History

- Garden, Alexander, May 23, 1755, in a letter to Cadwallader Colden (Colden 1921: 4:10)[30]

- “It gives me great pleasure that you give me leave to send Miss Colden’s Description of that new plant to any of my Correspondents as I had before sent it to Dr Whytt. . . Its now passed the Season of Seeds but I'll endeavour to procure Such as Miss Colden may want this year, tho my present Business confines me much to Town. I have not had an hour to spend in the woods this 2 months which makes me turn rusty in Botany.”

- Ellis, John, May 31, 1757, in a letter to Carl Linnaeus (Smith 1821: 1:85–86)[32]

- “You desire my advice in the affair of the Butneria and Beureria. . . If you will please to follow my advice, I would call it Gardenia, from our worthy friend Dr. Alexander Garden of S. Carolina, who will take it as a compliment from you, and may be a most useful correspondent to you, in sending you many new undescribed plants. . . He sent me this year great varieties of plants, but they have all been taken by the french.” back up to History

- Ellis, John, April 25, 1758, in a letter to Carl Linnaeus (Smith 1821: 1:92–93)[32]

- “I have lately received a letter from Dr. Garden, of Charles Town, South Carolina. He has not received any letters from you, but is very desirous of a correspondence with you. If you send a letter enclosed to me, I will forward it to him. He is well worth your friendship, for he is very ingenious, and a sensible observer of Nature.

- “He has sent me some new Genera which he has lately discovered, but I wait for the specimens of the plants to examine them by. He writes in his character of the Halesia that it as four kernels inclosed in the stone, and ranks it among the Monadelphia. . .

- “Some of the seeds that he sent me are now growing, so that we hope to naturalize this plant in England.

- “If you want a correspondent here that is a curious gardener, I shall recommend you to Mr. James Gordon, gardener, in Mile End, London. . . He has more knowledge in vegetation than all the gardeners and writers on Gardening in England put together, but is too modest to publish any thing. If you send him any thing rare, he will make you a proper return. We have got a rare double Jessamine [Gardenia Florida] from the Cape, that is not described; this man has raised it from cuttings, when all the other gardeners have failed in the attempt.”

- Ellis, John, July 21, 1758, in a letter to Carl Linnaeus (Smith 1821: 1:99–100)[32]

- “Mr. Collinson, Ehret, and I were the other day at Mr. Warner’s a very curious gentlemen, at Woodford near this City, to see his rare plant like a Jasmine, with a large double white flower, very odiferous, which he received about four years ago from the Cape of Good Hope. The flowers are so large, that a specimen, which he gave me to dissect, was four inches across from the extremities of the limb.

- “This Mr. Miller has described to be a Jasmine, in his Dictionary now publishing, and in his figures of Plants. . .

- “If you find this plant to be no Jasmine, but an undescribed genus, you will oblige me in calling it Warneria after its worthy possessor.”

- Ellis, John, June 13, 1760, in a letter to Carl Linnaeus (Smith 1821: 1:129–30)[32]

- “I have sent you. . . a collection of seeds which I received from our mutual friend Dr. Garden; some of them are covered with tallow, and some with myrtle-wax. . .

- “I desire you would please to call Mr. Warner’s Jasmine Gardenia, which will satisfy me, and I believe will not be disagreeable to you. . .

- “I shall write to Dr. Garden this day, that I have desired you to give the name of Gardenia to the Jasmine, which I am persuaded he will esteem as a favour; at the same time I shall send him Mr. Ehret’s curious print of it, coloured by himself.” [Fig. 3] back up to History

- Linnaeus, Carl, August 1760, in a letter to John Ellis (Smith 1821: 1:134)[32]

- “I shall obey your orders as to the names of plants; but if I may without reserve lay open my mind to you, I could have wished that the supposed Jasmine might have been called Warneria, after the person who has first cultivated it in Europe. Gardenia being applied to some genus first discovered by Dr. Garden. I wish to guard against the ill-natured objections, often made against me, that I name plants after my friends, who have not publicly contributed to the advancement of science. If therefore I confer this honour on those who have discovered the respective plants, no objection can arise, not can I be charged with infringing my own rules.” back up to History

- Collinson, Peter, September 15, 1760, letter to John Bartram (Bartram 1992: 493–94)[33]

- “Horse Sugar seems to be the Ligustrium of Catesby among the Specimens are many Charming plants Could Garden send seeds of them—the fine Clematis with Blewish reflex’d Flowers grows Luxriously in my Garden as Does the Spice Tree which keeps flowering all the Summer & perfumes all the Garden cannot be more Vigorous in its own Climate. . . though hath brought many specious plants to Light—[James?] Gordon longs for them but cannot see how he can get them unless Docr Garden can help Him—pray recommend Gordon to Him—He will not prove ungratefull if the Docr will inform Him of his Wants in the Vegitable Way—Send his List to Him.”

- Garden, Alexander, October 25, 1760, in a letter to John Bartram (Bartram 1992: 498)[33]

- “I have received two very kind letters from you since you left this place. . . Ever since I saw you I have lived in a greater hurry than when I had the pleasure of your agreeable company. Often since our parting have I reflected with concern that I had then so little time to enjoy you. . . Your plants in my Garden thrive surprisingly well & they are now ready for your Boxes—one or two are dead—As I met Lately with [James] Lee on Botany [An Introduction to Botany (1760)] I bought two copies one of which I have sent you & beg you’ll accept of it. . . Inclosed you have a letter from Mrs. Logan which has been with me some time for want of an opportunity.” back up to History

- Garden, Alexander, n.d. [c. January 1761], in a letter to John Ellis (Smith 1821: 1:501, 505, 506)[32]

- “Your compliment of Gardenia was most acceptable to me, and you need not doubt I shall gratefully remember it. Has Linnaeus adopted it?

- “I must beg that you would send me two or three more plates of the Gardenia, after it as received Dr. Linnaeus’s sanction; or any other of Ehret’s curious productions.

- “I showed to Mr. Bartram all my new plants, and gave him specimens; at the same time I told him that I intended to publish them all by themselves; those he mentioned to you were some of them. Several of them I had brought into my own little garden. An account of which you will have soon. . .

- “Pray send me one or two young plants of the Gardenia.”

- Logan, Martha Daniell, February 20, 1761, in a letter to John Bartram (Bartram 1992: 506)[33]

- “[list of bulbs]. . . Horsenecks, the Last Named & a little Seed of Slips of the Tree you Call the Snowball is what I am particularly Desirous of & they are not to be had from England for I have sent for them In several of my Lists but Never got one. I find they Doe very well with us for Doctor Garden has a good many roots Now bluming.” back up to History

- Bartram, John, May 22, 1761, in a letter to Peter Collinson (Bartram 1992: 517)[33]

- “Dr. Garden is so hurried as he knows plants well & where thay grow.”

- Garden, Alexander, February 23, 1761, in a letter to John Bartram (Bartram 1992: 507–8)[33]

- “I received your kind letter with your present of apples & plants. . . You made me very happy in the Newfoundland spruce, Hemlock, Fir & Kalmia, I wanted these very much & you gave me fine thriving plants. The others viz the Lavendar [sic], Sabina & Rhamnus with the Fraxinellas are all growing beautifully so that I expect to have great pleasure in them all Summer.

- “I hope you may have like pleasure in those that I now send you I need not tell you to plant them out immediately & in a shady moist place—The Box is rather too full, but the reason is, my not choosing to remove the earth from the roots of the plants as they grew, so that earth taken up with them soon filled up the Box. Your four Umbrellas are all alive & very thriving as is the great magnolia. The Atamasco Lilies are all alive; the Four-Leafed Bignonia, and the fine blue purple flower.

- “I could not find the Worm-grass root, so that I am afriad it is dead; but I shall soon replace it to you with some others. The Asarum, and Solanum triphyllum [Trillium] are both in good health, and blooming. I sincerely wish they may arrive safe.

- “How eminently happy are these hours which the humble & philosophic mind spends in investigating & Contemplating the inconceivable beautifies & mechanism of the works of nature. . .

- “N.B. I should be much obliged to you for some Hyacinths, some Narcissus with the largest Nectariums—we call these Horsenecks. I have one or two Persian irises that blossom beautifully. If you could spare some more I should be glad of them or any other bulbous root—

- “I have put on board a letter from Mrs. Logan with some seeds in it.” back up to History

- John Ellis, April 8, 1761, in a letter to Alexander Garden (Smith 1821: 1:506)[32]

- “I. . . am as much pleased with the very fine collection of seeds you sent me, so curiously preserved, as you can be with the Gardenia. Linnaeus has actually adopted it among his new genera. . . It will surprize people when they know that a nurseryman, James Gordon, in less than three years, has made £.500 from four cuttings of a plant. Every body is in love with it, and you may depend on having a plant of it from me; for as it is a double flower, besides being the native of a warm climate, it produces no seeds here.

- “I have bought two more coloured prints of it, wich shall be sent by the ships in June; for I fear these stragglers may be taken by the enemy. It has given great jealousy to our botanists here, that I have preferred you to them; but I laugh at them, and know I am right; for, without flattery, you have done more service, and I have obliged more people through your means, than they have in their power to do.”

- Garden, Alexander, June 17, 1761, in a letter to John Bartram (Bartram 1992: 521)[33]

- “I admire your variety of pancratiums & rejoice in your happiness—The Loblolly Bay, Dard Pomegranete & yellow wood have perished & all but those I Sent you—I could not get Beureria [Calycanthus] when I sent the Box & my own had died in the winter, but I’ll try to get two or three plants this year—Pray remember to let me have some of your fine Bulbs especially Hyacinths, & the Daffodil with the large long pinched nectatium [sic] & whatever Else you please. Let me know your sons Duration & Address & I’ll send him some Pink root.

- “This will be delivered to you by a Lady [unidentified] whom I have the honour to be acquainted with, & who has a very pretty taste for flowers & the culture of Curious plants. She intends to pay you a visit while she stays at Philadelphia & I take the liberty to beg your Civilities to her, not doubting but it will give you joy to see a Lady coming so far to view & Admire your Curiosities.”

- Bartram, John, November 8, 1761, in a letter to Peter Collinson (Bartram 1992: 538)[33]

- “I have just received two fine Cargoes of fresh plants from South Carolina from two different Correspondents but dr Garden hath sent me nothing this fall but thanks in A letter to my son for A large parcel of bulbous roots I sent him he is so hurried in his practice that he can hardly go out of town but I am packing up A chest of Apples for him which I hope will make him speak by next spring.”

- Logan, Martha Daniell, n.d. [summer 1761], in a letter to John Bartram (Bartram 1992: 523)[33]

- “[list of plants she would like] P.S. When you Send or Wright to me againe be pleased to Direct for me to the Caire of John Logan Marchant in Charles Town. For Dr. Garden has so much business he has not time to Think of me, Wherefore your Letters have Some times Layen a good While & I never Known of them.”

- Garden, Alexander, n.d. [February 15, 1762], in a letter to John Bartram (Bartram 1992: 548–49)[33]

- “I have this moment finished a letter for your Sons [Isaac and Moses], for whom I have much esteem on your Acct. and likewise for their own merit; It will give me much pleasure to serve them in any thing that I can from this place & I hope our acquaintance will be of mutual advantage.

- “By Capt Noarth I received your most obliging & very agreeable letter. . . Your observations are many valuable, curious & diverting I have read them over & over with much satisfaction & would willingly enter upon a discussion of each particular if my Continual hurry of business permitted me to have a leisure hour, but alas my Dr Friend ever since I had the pleasure of seeing you here I have never been three miles from town since that time so that now Botany is quite neglected by me, but I rejoice to hear of the keenness & Ardor with which you daily advance in the Science & cultivate your mind & that Study. . . Happy—thrice Happy are you whose comfortable easy & retired situation gives you this noble opportunity of exercising those faculties with which God has blessed you. . .

- “The time may come when I will follow with more care & quickness than my present situation will permit. . .

- “I have sent you a small quantity of Rice which I hope you will please to accept of as some small acknowledgt [sic] of the many favours which I have received at your hand.”

- Garden, Alexander, February 12, 1866, in a letter to John Bartram (Bartram 1992: 658)[33]

- “I am here, confined to the sandy streets of Charleston, where the ox, where the ass, and where men as stupid as either, fill up the vacant space, while you range the green fields of Florida, where the bountiful hand of Nature has spread every beautiful and fair plant and flower, that can give food to animals, or pleasure to the spectator.

- “Pray, out of the abundance of what you see, send me some curiosities, particularly seeds for my garden. But let these be confined wholly to what is new and curious. Some young plants, in a box, would be very acceptable.”

- Garden, Alexander, January 26, 1771, in a letter to John Ellis, January 26, 1771 (Smith 1821: 1:588)[32]

- “I am vastly pleased to hear of my namesake the Gardenia thriving so well with you, and should be very glad to get a plant of it, as I now have a piece of ground where I could cultivate it.”

- Garden, Alexander, July 24, 1789, in a letter to George Ogilvie (The Southern Literary Journal 18: 132–34)[34]

- “A few unconnected remarks on the situation and productions of Otranto [and] the Reasources of Carolina are inclosed. Such of them as you can weave into a description of that once beautiful and roman tick spot, may show what a Carolina situation ornamentted with only the natural productions of the Country can arrive at when so laid out.—The magical deception of the winding of Streight walks was not the least ornament of the garden for while walking in the garden you saw no straight walk & yet when turning and walking along the Bank of the river you saw none but Streight walks & not one of these winding walks thro the meanders of which you had visited all parts of the Garden while in it. And what is it now—possessed by a Goth! It sickens my soul to think of it.

- “Diversified grounds—Hill & Dale—A fine winding River—The opposite banks covered with tall primaeval trees with many a flourishing shrub making the most picturesque background. The river plenteously stored with a variety of Fish—the labrus sapidus or large voracious fresh water trout—The blue bream the most delicate and sweetest of fishes. . .

- “The house on the top of the hill commanding a fine prospect of the adjacent grounds and many different views of the meanderings of the River—guarded on the West from the afternoon’s sun by two large Liriodendrons or Tulip trees full of foliage and beautiful Blossoms during May June and part of July. Remember the large Liriodendron between the fish ponds rising eighty feet without a branch then spreading out into a large head having a large opening in the middle thro which the full moon about an hour high was seen from the Piazza of the house —Never was Cynthia seen so much to advantage before having not the simple fig leaf that Mother Eve resorted to but a full grown beard of tulip tree leaves and flowers. Had Endymion seen her thus arrayed what would he have said?

- “Near the house is a rural Library overshaddowed with an Umbrageous Catalpa & Lofty magnolia under Cover of which the first Company of the world reside [Milton, Tasso, Ariosto, Gay, Voltaire, Horace, Theocritus, Thompson]. . . Lineaus & Bufon accompany you to the Fields —Sir Issac & Cassini to the Celestial dance.

- “The ponds full of fish Juletta a successful fisher for Perch, Carp, Blue Bream &c.

- “The River at different seasons Covered with Ducks of Various kinds: . . the Mandarine Ducks—the blue winged teal and even the alligator in plenty. . . .

- “The gently hanging garden where Art only gives easy access to the Various inimitable productions of Nature from the early and mildly blushing Atamasco Lily to the modest Moccasine flower the pride of the meadows surrounded by the jessamines, orange coloured asclepias, the Candid Crinums, the Azure Lobilias and purple Iuccas[?] and day Gentianellas— . . Leaving the pearled Lobelia, the rich velvety Erythrina or Corrollodendrons—the blushing rose Coloured Accacia and in the number and magnitude of its clusters of flowers—to face the solsticial sun—The Andromedas—The Iteas—The Cyrilla—stillingia—The styrax, the Stewartia—The Illicium—all beautiful flowering Shrubs.

- “The Chionanthus.

- “The Magnolia altissima, the Proudest of the Vegetable kingdom, challenging both Indies in the rich Verdure of its foliage and Excelling Every Vegetable in the Magnitude and grandeur of its flowers—

- “The Magnolia Glauca, or Sweat flowering Bay, scenting all the Circumambient air with its fragrance.

- “The Calycanthus or sweet scented shrub diffusing an Aromatick fragrance seemingly a Compound of Strawberry, Pineapple, & the Clove—called sometime by the envied name of Bubby Blossom from the Ladies often carrying them in their bozoms.

- “The Kalmia or Callicoe flower, a beautiful shrub.

- “The Borders deakt with full blown Illiciums-Kalmias Erythrinas Calycanthus-Accacia Coccinea[?]—Umbrella Magnolias-Stewartia Ptelias—Styrax—Itea Cyrilla and many other aromatick and flowering shrubs give a lovely glow to the gardens of Otranto that your cold bleak gardens of Albion can never see or produce.

- “The Liriodendron, Magnolia Gordonia, or Loblolly Bay—the Catalpa—the large flowering Cornus—the Chionanthus—the Halesia, all large trees overshadow the Lesser greatly.

- “The yellow Jessaminy rich in the wallflower smell, luxriantly covering the tallest trees mingles its fragrant flowers with the Snow Drop or Chionan thus together with the Periclymenum or Scarlet woodbine.

- “These invite a thousand warblers—the Mocking bird. The Nonpareil, the Last in beauty of colours and the first in variety of notes exceeding all known birds—

- “Innumerable hosts of fireflies—

- “A storm of thunder and lightning.

- “Fair Peaches—the Kennedy Peach when full ripe exceeding in richness and flavour any other fruit or what even fancy can suggest—a taste the cold clime of Albion with all her art can never Emulate.”

- Ogilvie, George, 1790, describing Alexander Garden’s villa, Otranto, in “Carolina; or, The Planter” (The Southern Literary Journal 18: 67–76),[35]

- “And lo! my friend, where all the muse demands,

- “On Goose-creeks banks thy own Otranto stands!

- “Where pleas’d and wond’ring as we thrid the maze,

- “We doubt what beauty first demands our praise

- “The river bounded by the impervious shade,

- “The smooth green meadow, or the enamel’d glade,

- “Where all the pride of Europe’s florist yields

- “To the assembled wildings of our fields;

- “Tho’ herewith brighter tints the tulip glows,

- “And richer fragrance scents Damascus’ rose. . .

- “Whilst yet unnam’d the graet Magnlia bloom’d,

- “And numbler Glauca trackless wilds perfum’d.

- “Here Pales seems with Flora to have strove,

- “To blend the beauties of the lawn and grove. . .

- “Here early blossoms deck the unfledg’d Thorn,

- “And yellos Jasmines leafless trees adorn.

- “Bright as the blush of Venus when she loves,

- “Sweet as the woodbine of her Paphean groves,

- “Th’ Azalea climbs the Cypress loftier bough,

- “And Periclymenons low shaded blow,

- “Blending their lovely tubes of roseat hue,

- “With the Glycine’s variegated blue.

- “From tree to tree the flow’ry tindrils rove

- “Till one continu’d garland binds the grove—

- “Winding through shady walks, we slow descend,

- “To skirt the mead, or trace the river’s bend. . .

- “We mark the white Accasia all alive

- “With Bees, or see the Orange drain the hive,

- “Whilst fragrant Calycanths appear to bring

- “The fruits of Autumn midst the flow’rs of Spring;

- “White Chionanths, with flaky fringe, display

- “December freezing in the lap of May,

- “As Periclymenons luxuriant throw

- “Their glowing wreaths around the mimic snow;

- “And yellow Jasmines interweave between,

- “Their golden blossom, and their em’rald green. . .

- “Here Qamoclits their blushing flow’rs renew,

- “Ere rising suns exhale the morning dew;

- “As if asham’d the tell-tale morn should see

- “Their tender limbs intwine yon vig'rous tree. . .

- “There midst the grove, with unassuming guise

- “But rural neatness, see the mansion rise!. . .

- “Nor distant far, where Liriodendrums spread,

- “More rich than Persian Looms, a painted shade,

- “A Temple, sacred to each Muse, we find,

- “Stor’d with the noblest treasures of the mind.”

Images

Notes

- ↑ Alexander Garden to John Ellis, March 22, 1756, quoted in James Edward Smith, A Selection of the Correspondence of Linnaeus, and Other Naturalists: From the Original Manuscripts, 2 vols. (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, 1821), 1: 366–67, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Notes from the Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh (Edinburgh: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1921), 12:vii, ix; and Edmund Berkeley and Dorothy Smith Berkeley, Dr. Alexander Garden of Charles Town (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1969), 15–20, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Garden to Charles Alston, February 18, 1756, quoted in Berkeley and Berkeley 1969, 24, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Berkeley and Berkeley 1969, 24–25, 27, view on Zotero; see also Charles Alston, Index Plantarum, Præcipue Officinalium, Quæ, in Horto Medico Edinburgensis (Edinburgh: W. Sands, A. Brymer, A. Murray, and J. Cochran, 1740) and Francesco Eulaio Savastano, I Quattro libri delle cose botaniche del P. Francesco Eulalio Savastano, . . . colla traduzione in verso sciolto italiano di Giampetro Bergantini, . . . e colle annotazioni di esso autore ed altre aggiuntevi (Venice: P. Bassaglia, 1749).

- ↑ Berkeley and Berkeley 1969, 29, 35–39, 185–86, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Geraldine M. Meroney, Inseparable Loyalty: A Biography of William Bull (Norcross, GA: The Harrison Company, 1991), 52, 56, view on Zotero; James Raven, London Booksellers and American Customers: Transatlantic Literary Community and the Charleston Library Society, 1748–1811 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2002), 223, view on Zotero; and Berkeley and Berkeley 1969, 33, 35, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Berkeley and Berkeley 1969, 35, 66, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Smith 1821, 1: 343, view on Zotero; Berkeley and Berkeley 1969, 53, 40–43, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Berkeley and Berkeley 1969, 43–45, 69, 74, 96, view on Zotero.

- ↑ The plant is now most commonly known as Virginia marsh-St. John’s-wort (Triadenum virginicum). See Alexander Garden [and Jane Colden], “The Description of a New Plant; by Alexander Garden, Physician at Charleston in South Carolina,” in Essays and Observations, Physical and Literary (Edinburgh: G. Hamilton and J. Balfour, 1756), 2:1–5, view on Zotero; see also Cadwallader Colden, The Letters and Papers of Cadwallader Colden, Collections of the New-York Historical Society for the Year 1921, 9 vols. (New York: The New York Historical Society, 1923), 5:10, view on Zotero; Daniel J. Philippon, “Gender, Genius, and Genre: Women, Science, and Nature Writing in Early America,” in Such News of the Land: U.S. Women Nature Writers, ed. Thomas S. Edwards and Elizabeth A. De Wolfe (Hanover: University Press of New Hampshire, 2001), 24–25, view on Zotero; Smith 1821, 1:366–67, view on Zotero; and Berkeley and Berkeley 1969, 47–48, 53, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Hoffmann and Van Horne 2004, xx, view on Zotero, and Berkeley and Berkeley 1969, 43–46, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Berkeley and Berkeley 1969, 62–63, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Garden to Henry Baker, March 14, 1756, quoted in Berkeley and Berkeley 1969, 89, view on Zotero.

- ↑ James L. Reveal and Margaret J. Seldin, “On the Identity of Halesia Carolina L. (Styracaceae),” Taxon 25 (1976): 123–40, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Edmund Berkeley, “The History of the Naming of the Loblolly Bay,” Journal of the History of Biology 3 (Spring 1970): 149–54, view on Zotero, and Berkeley and Berkeley 1969, 74–78, 113, 158–162; see also pages 114–19, 128–29 for Garden’s subsequent attempts to have a plant named Ellisia in Ellis’s honor, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Smith 1821, 1:82, view on Zotero, and Berkeley and Berkeley 1969, 53, 74, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Ellis, “Of the Plants Halesia and Gardenia. In a Letter from John Ellis, Esq. R.R.S., to Philip Carteret Webb, Esq, F.R.S,” The Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London,11 (1809): 508–9, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alexander Garden to John Frederick Gronovius, March 15, 1755, quoted in Berkeley and Berkeley 1969, 52–53; for Garden’s plant and seed exchanges, see also pages 54–61, 69, 71–73, 76, 86, 91–92, 96, 98, 99, 104–5, 133–35, 213, 348–52, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Berkeley and Berkeley 1969, 90–91, 112, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Sir James Edward Smith, “Introductory Discourse on the Rise and Progress of Natural History,” April 8, 1788, quoted in Berkeley and Berkeley 1969, 329, view on Zotero. See also Margaret Denny, “Linnaeus and His Disciple in Carolina: Alexander Garden,” Isis 38 (1948): 161–74, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Bartram, The Correspondence of John Bartram, 1734–1777, ed. Edmund Berkeley and Dorothy Smith Berkeley (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1992), 498, view on Zotero; Berkeley and Berkeley 1969, 151–154, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Berkeley and Berkeley 1969, 154, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Berkeley and Berkeley 1969, 153, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Harriott Horry Ravenel, Eliza Pinckney (New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1896), 102, view on Zotero, and Berkeley and Berkeley 1969, 34, 155–56; see also pages 101–3, 119–21, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Bartram and Francis Harper, “Diary of a Journey through the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida from July 1, 1765, to April 10, 1766,” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society n.s. 33, part 1 (December 1942): 13–15, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Joseph I. Waring, “Correspondence between Alexander Garden, M.D., and the Royal Society of Arts (Continued),” The South Carolina Historical Magazine 64 (1963): 93, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Berkeley and Berkelely 1969, 251–52, view on Zotero.

- ↑ David Ramsay, The History of South-Carolina: From Its First Settlement in 1670, to the Year 1808, 2 vols. (Charleston: David Longworth, 1809), 2:471–72, view on Zotero.

- ↑ David S. Shields, Oracles of Empire: Poetry, Politics, and Commerce in British America, 1690–1750 (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1990), 91, view on Zotero, and David S. Shields, “George Ogilvie’s ‘Carolina; Or, The Planter’ (1776),” The Southern Literary Journal 18 (1986): 13, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Cadwallader Colden, The Letters and Papers of Cadwallader Colden, Collections of the New-York Historical Society for the Year 1919 (New York: The New York Historical Society, 1921), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Colden 1923, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 32.4 32.5 32.6 32.7 Smith 1821, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 33.4 33.5 33.6 33.7 33.8 33.9 Bartram 1992, view on Zotero.

- ↑ “The Letters of George Ogilvie and Alexander Garden,” The Southern Literary Journal 18 (1986): 117–34, view on Zotero.

- ↑ George Ogilvie, “George Ogilvie’s Narrative Poem ‘Carolina; Or, the Planter’ (1790),” Southern Literary Journal 18 (1986): 7–82, 102–12, view on Zotero.