Difference between revisions of "National Mall"

m (condition redux and overview cleanup) |

m (line spacing and hr standardization) |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

==Overview== | ==Overview== | ||

| − | |||

'''Alternate Names:''' Public Grounds<br/> | '''Alternate Names:''' Public Grounds<br/> | ||

'''Site Dates:''' 1791–present<br/> | '''Site Dates:''' 1791–present<br/> | ||

| Line 195: | Line 194: | ||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| − | < | + | <references/> |

| + | |||

| + | <hr> | ||

[[Category: Places]] | [[Category: Places]] | ||

Revision as of 16:25, August 20, 2018

The National Mall is a broad, tree-lined green in Washington, DC, that extends from the foot of Capitol Hill to the Washington Monument. It is a public space used for recreational activities, cultural events, and democratic discourse. Museums and gardens flank the north and south sides. The United States Capitol building lies to the east and the monuments of West Potomac Park lie to the west. Both as a national icon and a civic space, the Mall is a key landmark of the nation’s capital.

Overview

Alternate Names: Public Grounds

Site Dates: 1791–present

Site Owner(s): U.S. National Park Service

Associated People: Pierre-Charles L’Enfant (1754–1825, urban designer); Robert Mills (1781–1855, architect); Andrew Jackson Downing (1815–1852, landscape designer)

Location:Washington, DC

Condition: altered

View on Google maps

History

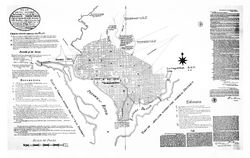

The origins of the National Mall can be traced to a preliminary plan for the city of Washington sketched by Thomas Jefferson in March 1791. Jefferson laid out the city in a gridiron formation, envisioning the Capitol building and the President’s House as opposite ends of a prominent east-west axis connected by "public walks" [Fig. 2].[1] Over the next several months, the military engineer Pierre-Charles L’Enfant expanded upon Jefferson’s ideas in his official plan for the city, which adapted abstract geometry to the natural topography of the site, which featured a park-like setting of rolling hills, a wooded terrain, and proximity to the Potomac River. Influenced by recent developments in French urban planning, L’Enfant’s ambitious design called for a “Grand Avenue, 400 feet in breadth, and about a mile in length” leading from “the Congress Garden” on Jenkins Hill (now Capitol Hill) to the “President’s park” and a “well-improved field” near the banks of the Potomac, which would be the site of a projected equestrian statue of George Washington (view citation). The view from that point back to the Capitol would feature a cascade falling from a height of forty feet down to a canal running alongside the Mall to the Potomac. L’Enfant conceived of the wide urban avenue as a social as well as a scenic space: a “place of general resort,” bordered by gardens and the stately residences of the city’s elite, as well as playhouses, assembly rooms, academies, “and all such sort of places as may be attractive to the l[e]arned and afford diver[s]ion to the idle” (view citation).[2] L’Enfant would later remark that he “changed the whole face of the city ground, from a savage wilderness into a compleat heden [sic] garden.”[3]

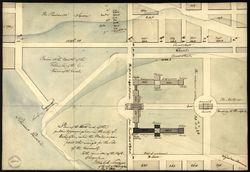

Development of the Mall stalled over the next several decades while a variety of alternative plans were advanced. Benjamin Henry Latrobe, then Supervising Architect of the United States Capitol, proposed a design in 1815 that called for a canal originating in a circular basin at the foot of the Capitol and running the full length of the Mall to a cascade and lagoon at the opposite end [Fig. 1]. Nothing came of this proposal, nor of others advanced by the architects Charles Bulfinch (in 1822) and Robert Mills (in 1831).[4] Sections of the Mall were cultivated on a piecemeal basis; for example, in 1821 the Columbian Institute began carrying out improvements on five acres at the Mall’s east end for a botanical garden, which included cultivating a hedge enclosure, excavating an elliptical pond with an island, laying out gravel walks, and planting borders with specimens of native and exotic trees and shrubs.[5]

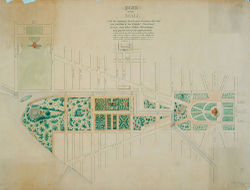

In 1841, as part of his design for the building that would ultimately house the Smithsonian Institution, Robert Mills submitted a comprehensive plan for a great public park extending from the Washington Monument to the Capitol. As conceived by Mills, the Mall would be laid out as a picturesque assemblage of gardens of contrasting styles: informal plantings and serpentine paths in the English style surrounding the Washington Monument and botanic gardens would be contrasted with more formal, geometric plantings near the Capitol [Fig. 3]. Mills’s design was novel for its holistic integration of architecture and landscape, as well as for its botanical emphasis, which reflected the influence of the contemporary English theory of the gardenesque formulated by J. C. Loudon.[6] At the same time, Mills’s design was consistent with the long-held objective of locating a publicly accessible botanic garden in the nation’s capital—an idea first broached in the 1790s by influential advocates including George Washington and Thomas Jefferson.[7] Mills’s plan had little immediate impact on the landscaping of the Mall, which remained in a undeveloped state in 1845, when a member of the Smithsonian Institution Building Committee “urged the expediency and policy of rescuing the Mall from its present state of degradation and of ornamenting it at least with the different trees of this country, and protecting it with a decent enclosure.”[8] That same year, 2,000 indigenous trees (representing 200 species and varieties) were planted on the Mall, and additional plantings and enclosures were added in the years that followed.[9] Robert Mills’s conception of the Mall as a locus for scientific inquiry and display, and his adoption of the romantic aesthetic of naturalism set the tone for future landscaping of the area.

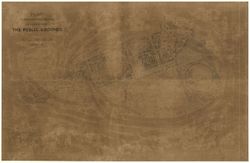

Botanical interests informed the landscape plan designed in 1851 by the architect and horticulturalist Andrew Jackson Downing, who conceived of the Mall as “a national park” and a “public museum of living trees and shrubs” that would both influence taste by providing an example of the natural style of landscape gardening (illustrated by a sequence of contrasting landscape “scenes”), and educate visitors to the popular and scientific names, habits, and growth of botanical specimens suited to Washington’s climate (view citation) [Fig. 4].[10] Rather than carry out Downing’s plan systematically, individual federal agencies developed portions of the Mall on an ad hoc basis, creating a loosely connected network of meandering walks, gardens, and groves.[11] Under the McMillan Plan of 1902, the existing landscape was cleared and leveled in order to create a more unified, open space with unobstructed vistas in keeping with the spirit of L’Enfant’s original plan. Landscape and hardscape construction projects continue to reshape the Mall and its surroundings into the 21st century. [12]

—Robyn Asleson

Texts

- L’Enfant, Pierre-Charles, June 22, 1791, describing in a report to George Washington his plans for Washington, DC (quoted in Caemmerer 1950: 151–53)[13] back up to history

- “I placed the three grand Departments of State contigous to the principle Palace and on the way leading to the Congressional House the gardens of the one together with the park and other improvement on the dependency are connected with the publique walk and avenue to the Congress house in a manner as most [must] form a whole as grand as it will be agreeable and convenient to the whole city which form [from] the distribution of the local [locale] will have an early access to this place of general resort and all along side of which may be placed play houses, room of assembly, accademies and all such sort of places as may be attractive to the learned and afford diversion to the idle.” [Fig. 5]

- L’Enfant, Pierre-Charles, August 19, 1791, describing his plans for Washington, DC (quoted in Caemmerer 1950: 157)[14]

- “The grand avenue connecting the palace and the Federal House will be magnificent, with the water of the cascade [falling] to the canal which will extend to the Potomac; as also the several squares which are intended for the Judiciary Courts, the National Bank, the grand Church, the play house, markets and exchange, offering a variety of situations unparallelled for beauty, suitable for every purpose, and in every point convenient, calculated to command the highest price at a sale.”

- L’Enfant, Pierre-Charles, January 4, 1792, from notes on “Plan of the City” describing Washington, DC (quoted in Caemmerer 1950: 163–65)[15] back up to history

- “F. Grand Cascade, formed of water from the sources of the Tiber.

- “G. Public walk, being a square of 1200 feet, through which carriages may ascend to the upper Square of the Federal House.

- “H. Grand Avenue, 400 feet in breadth, and about a mile in length, bordered with gardens, ending in a slope from the houses on each side. This Avenue leads to Monument A and connects the Congress Garden with the

- “I. President’s park and the

- “K. well-improved field. . . .” [Fig. 6]

- Robert Mills, c. 1804, describing the National Mall (quoted in Gallagher 1935: 1927)[16]

- “It is a most commanding and beautiful prospect, variegated with woods, cleared land, gentle mounts and vales, and the waters of the Potomac and Tiber Rivers in the distant view; while there is revealed a glimpse of the navy yard where eight frigates of the United States Navy lie in mooring.”

- Anonymous, January 2, 1808, describing in the Washington Expositor the National Mall, Washington, DC (quoted in O’Malley 1989: 99–100)[17]

- “At present these large appropriations afford an increase to the pasturage of the city, more beneficial to the poor citizens, than their culture in the ordinary courses. . . . by laying off those in their occupancy so as to afford ample walks open at seasonable hours and under proper regulations to the public, it will give to the city, much earlier than there is otherwise reasonable cause to hope for, agreeable promenades, as conducive to the health of the inhabitants, as to the beauty of the places.”

- Hunt, Henry, William P. Elliot, and William Thornton, 1826, describing the National Mall, Washington, DC (U.S. Congress, 19th Congress, 1st Session, House of Representatives, doc. 123, book 138)

- “That, with a view to promote the public good, and to ornament and improve the public grounds, they would recommend that the water of Tiber Creek be brought to the Capitol Square; and, after forming a reservoir, be carried in pipes to the Botanic Garden, and thrown up in a jet d'eau of 30 or 40 feet high, and then be used in watering the surrounding grounds. That a wall five feet high, with a stone coping, be put round the ground appropriated for a Botanic Garden; and that suitable buildings be erected, and the Garden be properly laid out, and cultivated as a National Garden; to effect which important national objects, a sum not exceeding 30,000 dollars will be required.”

- Commissioner of Public Buildings, June 9, 1827, describing the Columbian Institute, Washington, DC (quoted in O’Malley 1989: 133)[18]

- “The new section of the Washington Canal was laid out along a line drawn through the middle of the Capitol and of the Mall. The pathway, canal and plantation in the garden do not coincide with this line, but diverge from it at an acute angle.”

- Bulfinch, Charles, January 21, 1829, proposal to the House Committee on Public Buildings regarding the National Mall, Washington, DC (quoted in Rathburn 1917: 49)[19]

- “The Capitol being now finished with the exception of these particular objects, I beg leave to suggest that the public grounds immediately adjacent should conform in some degree to the importance and high finish of the building.”

- Mills, Robert, c. 1841, in a letter to Robert Dale Owen, describing the proposed Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC (Scott, ed., 1990: n.p.)[20]

- “Three spacious avenues (of the city) center within these grounds, which at some future day when improved will form three interesting vistas.”

- Mills, Robert, February 23?, 1841, in a letter to Joel R. Poinsett, describing his design for the National Mall, Washington, DC (Scott, ed., 1990: n.p.)[21]

- “Agreeably to your requisition to prepare a plan of improvement to that part of the Mall lying between 7th and 12th Street West for a botanic garden . . . I have the honor to submit the following Report. . . .

- “Drawing No. 1 presents a general plan of the entire Mall, including that annexed to the President’s house, with the particular improvement proposed of that part intended for the Institution and its objects. . . .[See Fig. 3]

- “The relative position of the Capitol, President’s House, and other public buildings are laid down, as also the position of the proposed buildings for the Institution; the adjacent streets and avenues are also shown, with the line of the Canal which courses through the City, at the foot of the Capitol hill to the Eastern Branch near the Navy Yard, thus making of the south western section, a complete island. . . .

- “The principle upon which this plan is founded is two fold, one is to provide suitable space for a Botanic garden, the other to provide locations for subjects allied to agriculture, the propagation of useful and ornamental trees native and foreign, the provision of sites for the erection of suitable buildings to accommodate the various subjects to be lectured on and taught in the Institution. . . .

- “The Botanic garden is laid out in the centre fronting and opening to the south. On each side of this the grounds are laid out in serpentine walks and in picturesque divisions forming plats for grouping the various trees to be introduced and creating shady walks for those visiting the establishments. . . .

- “A range of trees is proposed to surround three sides of the square which is intended to be laid open by an iron or other railing, the north side to be enclosed with a high brick wall to serve as a shelter and to secure the various hot houses and other buildings of inferior character.

- “The main building for the Institution is located about 300 feet south of the wall fronting the Botanic garden, from which it is separated by a circular road, in the centre of which is a fountain of water from the basin of which pipes are led underground thro’ the walks of the garden, for irrigating the same at pleasure, the fountains may be supplied from the canal flowing near the north wall of inclosure. . . .

- “By means of Groups and vistas of trees, picturesque views may be obtained of the various buildings and other such objects as may be of a monumental character and thus there would be an attraction produced which would draw many of our citizens and strangers to partake of the pleasure of promenading here.”

- Mudd, Ignatius, 1849, describing the grounds of the United States Capitol and the reconstruction of the National Mall, Washington, DC (U.S. Congress, 31st Congress, 1st Session, doc. 30)

- “A disposition on the part of Congress to make the public grounds what they were originally designed to be. . . . An ornament and attraction to the capital of the nation.”

- Downing, A. J., December, 1851, “The State and Prospects of Horticulture” (Horticulturist 6: 540–41)[22]

- “The plan [for a public ground in Washington] embraces four or five miles of carriage-drive—walks for pedestrians—ponds of water, fountains and statues—picturesque groupings of trees and shrubs, and a complete collection of all the trees that belong to North America. It will, if carried out as it has been undertaken, undoubtedly give a great impetus to the popular taste in landscape-gardening and the culture of ornamental trees; and as the climate of Washington is one peculiarly adapted to this purpose—this national park may be made a sylvan museum such as it would be difficult to equal in beauty and variety in any part of the world.”

- Downing, A. J., 1851, describing plans for improving the public grounds in Washington, DC (quoted in Washburn 1967: 54–55)[23] back up to history

- “My object in this Plan has been three-fold:

- “1st: To form a national Park, which should be an ornament to the Capital of the United States; 2nd: To give an example of the natural style of Landscape Gardening which may have an influence on the general taste of the Country; 3rd: To form a collection of all the trees that will grown in the climate of Washington, and, by having these trees plainly labelled with their popular and scientific names, to form a public museum of living trees and shrubs where every person visiting Washington could become familiar with the habits and growth of all the hardy trees. [Fig. 7]

- “The Public Grounds now to be improved I have arranged so as to form six different and distinct scenes: viz.

- “1st: The President’s Park or Parade.

- “This comprises the open Ground directly south of the President’s House. Adopting suggestions made me at Washington I propose to keep the large area of this ground open, as a place for parade or military reviews, as well as public festivities or celebrations. A circular carriage drive 40 feet wide and nearly a mile long shaded by an avenue of Elms, surrounds the Parade, while a series of foot-paths, 10 feet wide, winding through thickets of trees and shrubs, forms the boundary to this park, and would make an agreeable shaded promenade for pedestrians.

- “I propose to take down the present small stone gates to the President’s Grounds, and place at the end of Pennsylvania Avenue a large and handsome Archway of marble, which shall not only form the main entrance from the City to the whole of the proposed new Grounds, but shall also be one of the principal Architectural ornaments of the city; inside of this arch-way is a semicircle with three gates commanding three carriage roads. Two of these lead into the Parade or President’s Park, the third is a private carriage-drive into the President’s grounds; this gate should be protected by a Porter’s lodge, and should only be open on reception days, thus making the President’s grounds on this side of the house quite private at all other times. . . .

- “2nd: Monument Park.

- “This comprises the fine plot of ground surrounding the Washington monument and bordered by the Potomac. To reach it from the President’s Park I propose to cross the canal by a wire suspension bridge, sufficiently strong for carriages, which would permit vessels of moderate size to pass under it, and would be an ornamental feature in the grounds. I propose to plant Monument Park wholly with American trees, of large growth, disposed in open groups, so as to al[l]ow of fine vistas of the Potomac river. . . .

- “4th: Smithsonian Park or Pleasure Grounds.

- “An arrangement of choice trees in the natural style, the plots near the Institution would be thickly planted with the rarest trees and shrubs, to give greater seclusion and beauty to its immediate precincts.

- “This Park would be chiefly remarkable for its water features. The Fountain would be supplied from a basin in the Capitol. The pond or lake might either be formed from the overflow of this fountain, or from a filtering drain from the canal. The earth that would be excavated to form this pond is needed to fill up low places now existing in this portion of the grounds.

- “6th: The Botanic Garden.

- “This is the spot already selected for this purpose and containing three green-houses. It will probably at some future time, be filled with a collection of hardy plants. I have only shown how the carriage-drive should pass through it (Crossing the canal again here) and making the exit by a large gateway opposite the middle gate of the Capitol Grounds. . . .

- “The pleasing natural undulations of surface, where they occur, I propose to retain, instead of expending money in reducing them to a level. The surface of the Parks, generally, should be kept in grass or lawn, and mown by the mowing machine used in England, by which, with a man and horse, the labor of six men can be done in one day. . . .

- “A national Park like this, laid out and planted in a thorough manner, would exercise as much influence on the public taste as Mount Auburn Cemetery near Boston, has done. Though only twenty years have elapsed since that spot was laid out, the lesson there taught has been so largely influential that at the present moment the United States, while they have no public parks, are acknowledged to possess the finest rural cemeteries in the world. The Public Grounds at Washington treated in the manner I have here suggested, would undoubtedly become a Public School of Instruction in every thing that relates to the tasteful arrangement of parks and grounds, and the growth and culture of trees, while they would serve, more than anything else that could be devised, to embellish and give interest to the Capital. The straight lines and broad Avenues of the streets of Washington would be pleasantly relieved and contrasted by the beauty of curved lines and natural groups of trees in the various parks. By its numerous public buildings and broad Avenues, Washington will one day command the attention of every stranger, and if its un-improved public grounds are tastefully improved they will form the most perfect background or setting to the City, concealing many of its defects and heightening all its beauties.”

Images

Other Resources

Library of Congress Authority File

The Cultural Landscape Foundation

National Mall Plan (National Park Service)

Notes

- ↑ Richard W. Stephenson, “A Plan Whol[l]y New”: Pierre Charles L’Enfant’s Plan of the City of Washington (Washington, DC: Library of Congress, 1993), 17–19, see also 38–43, view on Zotero; Therese O’Malley, “Art and Science in American Landscape Architecture: The National Mall, Washington, DC 1791–1852,” PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1989, 15–21, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Michael J. Lewis, “The Idea of the American Mall,” in The National Mall: Rethinking Washington’s Monumental Core, ed. Nathan Glazer and Cynthia R. Field (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008), 13–15, view on Zotero; Pamela Scott, “‘This Vast Empire’: The Iconography of the Mall, 1791–1848,” in The Mall in Washington, ed. Richard Longstreth, Studies in the History of Art, Center for Advanced Studies in the Visual Arts, Symposium Papers, XIV (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1991), 39–40 and 55, n.20, view on Zotero; O’Malley 1989, 26–48, 95–97,view on Zotero; H. Paul Caemmerer, The Life of Pierre-Charles L’Enfant, Planner of the City Beautiful, The City of Washington (Washington, DC: National Republic Publishing Company, 1950), 151–53, 157–59, 163–65, view on Zotero.

- ↑ O’Malley 1989, 50, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Scott 1991, 46–50, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Scott 1991, 46, view on Zotero; Therese O’Malley, “‘Your Garden Must Be a Museum to You’: Early American Botanic Gardens,” Huntington Library Quarterly 59 (1996): 218–20, view on Zotero; O’Malley, 1989, 122–36,view on Zotero.

- ↑ O’Malley 1989, 150–51, 158–61, 169–72, view on Zotero.

- ↑ O’Malley 1996, 213–26, view on Zotero; Scott 1991, 48–49, view on Zotero; O’Malley 1989, 98–105, 112, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Quoted in O’Malley 1989, 181, view on Zotero.

- ↑ O’Malley 1989, 180–82, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas J. Schlereth, “Early North American Arboreta,” Garden History 35 (2007): 211–13, view on Zotero; Kirk Savage, Monument Wars: Washington, DC, the National Mall, and the Transformation of the Memorial (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, 2005), 70–73, view on Zotero; Therese O’Malley, “‘A Public Museum of Trees’: Mid-Nineteenth Century Plans for the Mall,” in Longstreth, 1991, 65–72, view on Zotero; O’Malley 1989, 196–98, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Savage 2005, 75, view on Zotero; David C. Streatfield, “The Olmsteds and the Landscape of the Mall,” in Longstreth, 1991, 117–18, view on Zotero; O’Malley 1991, 72, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Peter R. Penczer, The Washington National Mall (Arlington, VA: Oneonta Press, 2007), 21–121, view on Zotero; Sue Kohler and Pamela Scott, eds., Designing the Nation’s Capital: The 1901 Plan for Washington, DC (Washington, DC: U. S. Commission of Fine Arts, 2006), view on Zotero; Savage 2005, 147–313, view on Zotero; Therese O’Malley, “The Mall: 1992–2002,” in Longstreth, 2002, ix–xii, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Caemmerer 1950, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Caemmerer 1950, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Caemmerer 1950, view on Zotero.

- ↑ H. M. Pierce Gallagher, Robert Mills, Architect of the Washington Monument, 1781–1855 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1935), view on Zotero.

- ↑ O’Malley 1989, view on Zotero.

- ↑ O’Malley 1989, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Richard Rathburn, “The Columbian Institute for the Promotion of Arts and Sciences,” United States National Museum’s Bulletin 101 (1917): 45–46. view on Zotero

- ↑ Pamela Scott, The Papers of Robert Mills (Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Resources, 1990), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Scott 1990, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Andrew Jackson Downing, “The State and Prospects of Horticulture,” The Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 6, no. 12 (December 1851): 537–41, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Wilcomb E. Washburn, “Vision of Life for the Mall,” AIA Journal 47, no. 3 (March 1967): 52–59. view on Zotero