The Woodlands

Overview

Alternate Names: William Hamilton House; The Woodlands Cemetery

Site Dates: 1766–c. 1898

Site Owner(s): Andrew Hamilton c. 1676–1741; Andrew Hamilton II 1712–1747; James Hamilton; William Hamilton 1745–1813; James Hamilton 1774–1817; Margaret Hamilton 1768–1828; Mary Hamilton 1771–1849; The Woodlands Cemetery Company;

Associated People: George Hilton, gardener; Mr. Thomson, gardener; John McAran, gardener; John Lyon, gardener; Frederick Pursh 1774–1820, gardener;

Location: Philadelphia, PA · 39° 56' 44.56" N, 75° 12' 21.28" W

Condition: Altered

Keywords: Ancient style; Arbor; Border; Botanic garden; Bridge; Clump; Conservatory; Eminence; English style; Fence; Greenhouse; Grotto; Grove; Ha-Ha/Sunk fence; Hedge; Hothouse; Icehouse; Kitchen garden; Landscape gardening; Lawn; Modern style/Natural style; Nursery; Orangery; Orchard; Park; Piazza; Plantation; Pleasure ground/Pleasure garden; Plot/Plat; Portico; Pot; Prospect; Seat; Shrubbery; Statue; Terrace/Slope; Thicket; Vase/Urn; View/Vista; Walk; Wall; Wood/Woods; Yard

Other Resources: LOC; The Woodlands Official Websit; The Cultural Landscape Foundation; Historic American Buildings Survey Documents (Library of Congress);

The Woodlands, a country estate outside the city of Philadelphia, was famed in the late-18th and early-19th centuries as a leading example of English taste in architecture and landscape gardening, and for the extensive collection of indigenous and exotic plants formed by William Hamilton (1745–1813). The property was later converted into a rural cemetery.

History

Located just west of Philadelphia in Blockley Township, the property that became known as The Woodlands offered scenic beauty and a convenient location in the countryside when the prominent lawyer Andrew Hamilton (1676?–1741) purchased the first parcel of land in 1734. Upon his death, the plantation passed to Andrew Hamilton II (1710?–1747), who died just six years later, leaving the 350-acre property to his two-year-old son, William Hamilton (1745–1813).[1] William Hamilton took control of the plantation, which he named The Woodlands, at the age of twenty-one and, by the early 1770s, made the estate his primary residence.[2] According to Timothy Preston Long, The Woodlands soon became Hamilton’s “principal occupation and he zealously endeavoured [sic] to perfect it as a work of art and to provide for himself a place for contemplation and scientific inquiry in agreeable retirement.”[3] From his country retreat, Hamilton pursued his interests in architecture, botany, and landscape design.

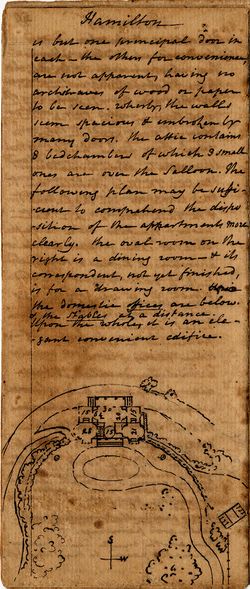

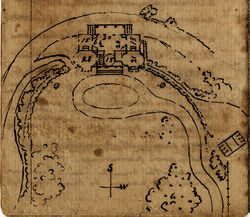

According to scholars, Hamilton likely erected a house on the property sometime around 1770. The structure’s dramatic siting—located on a bluff overlooking a bend in the Schuylkill River—not only provided Hamilton and his guests with “spectacular views” of the river and surrounding landscape but also guaranteed that travelers crossing the Schuylkill at Gray’s Ferry or (later) at a nearby bridge would have a clear view of Hamilton’s new home [Fig. 1]. Although little is known about the form of the original house, it was probably a rectangular structure with a gable roof and, as James A. Jacobs has argued, may have resembled John Penn’s manor house, The Solitude, which was built slightly later. Hamilton’s house at The Woodlands was especially notable for its grand, two-story tetrastyle portico in the Tuscan order—an extremely rare architectural feature during the colonial period—that faced the river and connected the interior of the house with the surrounding landscape.[4]

By 1779 Hamilton had expanded The Woodlands to nearly 550 acres and began making significant changes to the landscape.[5] In April 1779 Hamilton wrote to a friend that he had removed the “Central Wood” in order to improve the view of Philadelphia from the estate. He soon regretted the decision, however, after being tried (and acquitted) for treason—an experience that made the sight of the city “absolutely disgusting to [him]” (view text).[6] He also enclosed 100 acres of “Hill & Dale Woodland” to the north and east of his house “to make a small park.” To the south, the portico opened onto a lawn, which Hamilton spent an exorbitant sum to fertilize so that it would “shine” during the summer months (view text).[7] With the exception of this large parcel of land surrounding the mansion, by 1782 Hamilton had leased out most of the plantation—a decision that, as Long has noted, not only provided revenue to the proprietor but also freed up more time for his botanical pursuits.[8] Hamilton wanted significant architectural changes at The Woodlands as well, and, according to Jacobs, in 1784, he apparently hired Thomas Nevell (1721–1797), a well-known Philadelphia builder, to make plans to renovate the house, although the extent of the proposed changes remains unknown.[9] However, Hamilton halted the renovation in late 1784 when he left for England.[10]

Hamilton’s plans for his house and grounds at The Woodlands gained in ambition during his nineteen-month visit to England. While there, he made a special study of contemporary English landscape design by touring a number of country estates.[11] In September 1785 Hamilton wrote to friends and colleagues in Philadelphia of his desire to make “Some addition to the House, a stable & other offices at the Woodlands” (view text) and to make the grounds “smile in the same useful & beautiful manner” as the “variety & extent of the plantations” that he had seen in England (view text). Scholars have suggested that Hamilton very likely hired an architect while in England to create plans for the house but almost certainly laid out the gardens himself.[12] He greatly increased the variety of botanical specimens at The Woodlands during this time, shipping “a number of curious Flowering Shrubs and Forest Trees” to Philadelphia to be planted at The Woodlands (view text) and instructing his personal secretary, Benjamin Hays Smith, to make preparations for the construction of “a good nursery for trees, shrubs, flowers, fruit &c. of every kind.” Hamilton also asked Smith to send him the dimensions of the existing walks and ha-ha at The Woodlands, indicating that he had already begun working on a new planting plan by the fall of 1785 (view text).[13]

Upon his return to Philadelphia in July 1786, Hamilton carried out a major renovation and enlargement of his house at The Woodlands that doubled its original size—a project that occupied him until 1789.[14] The renovated mansion is still extant today. As it had prior to the renovation, the monumental two-story portico dominates the south façade, although Hamilton added wings on both sides featuring decorative niches and Venetian windows. Ionic pilasters and entablature adorn the north face—the side first seen by visitors approaching by land—and provide balance to the portico on the opposite, river-facing side of the house. The exterior of the stable-carriage house, constructed shortly after the renovation of the house was complete, echoes the late Georgian neoclassical design elements of the mansion, providing visual harmony for visitors who would see both structures when approaching the house by land.[15]

Even before Hamilton’s trip to England, the grounds at The Woodlands featured elements of the English, or natural style, of landscape design, including the enclosed park and rolling lawn. However, after his return, according to Aaron V. Wunsch, Hamilton “explicitly set out to remake the grounds as a horticultural showcase.”[16] He employed landscape principles popularized by British theorists and practitioners such as Lancelot “Capability” Brown (1716–1783), Thomas Whately (1726–1772), and Nathaniel Swinden (active c. 1768–1805). He eschewed the extensive use of topiary and architectural elements that had characterized the designs of older gardens near Philadelphia such as Belmont and Bush Hill.[17] According to one visitor, the garden at The Woodlands “consist[ed] of a large verdant lawn surrounded by a belt of walk, & shrubbery for some distance” [Fig. 2]. Visitors entered the garden either by way of the house’s portico or from the park through a small gate adjoining the mansion, and its tree-lined walks provided a route of nearly a mile, enabling visitors to enjoy the “many beauties of the landscape” as well as statues scattered throughout the garden (view text). Due to Hamilton’s efforts, The Woodlands became well-known as a paragon of the English style in the United States. In 1806 Thomas Jefferson, who frequently corresponded with Hamilton concerning their shared interest in horticulture and garden design, invited Hamilton to visit Monticello and see the improvements he was contemplating, noting, “You will have an opportunity of indulging on a new field some of the taste which has made The Woodlands the only rival which I have known in America to what may be seen in England” (view text).

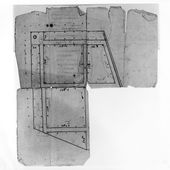

The walk through the garden terminated at a conservatory located northwest of the mansion, which, for many commentators, proved to be the highlight of a trip to The Woodlands. Hamilton had had a greenhouse at the estate as early as 1785, but construction of the larger complex known to early 19th-century visitors—which consisted of a greenhouse with a hothouse on either end—did not begin until 1792.[18] Hamilton’s greenhouse was well-known. Charles Drayton reported that the conservatory was “said to be equal to any in Europe,” containing “between 7 & 8000 plants,” and that it was occasionally visited by the professor of botany at the University of Pennsylvania and his students (view text).[19] David Hosack wrote in 1803 that Hamilton’s greenhouse provided the model for the one that he had recently begun building at the Elgin Garden in New York (view text). Hamilton’s conservatory was elaborate and included a system of scaffolding in the one-and-a-half-story greenhouse to hold plants in a form resembling “the declivity of a mountain” as well as “a cistern for tropic aquatic plants” in the hothouse (view text). His plant collection contained many rare species “procured at much trouble & expense from many remote parts of the globe” (view text), including an aloe that flowered in 1804 and was allegedly only the second plant to do so in the United States (view text).[20] Hamilton also grew a large variety of fruits and vegetables in his enormous five-sided, one and one-half acre kitchen garden, which was located northwest of the mansion and within walking distance to the hothouse and the stable [Fig. 3].[21]

Although “Hamilton was the principal creative force behind the design of his grounds,” as Wunsch has argued, his achievement at The Woodlands was only possible through the assistance of “a transatlantic network of botanists and nurserymen” that provided Hamilton with foreign plants and flowers and through the labor of a large team of workers who cared for his gardens. Smith was largely responsible for realizing Hamilton’s plans, frequently receiving detailed instructions from Hamilton when the proprietor was away from the estate.[22] Prior to Hamilton’s trip to England, a gardener named Mr. Thomson lived and worked at The Woodlands.[23] George Hilton, an African American man who had been indentured to Hamilton since at least 1781, also worked in the gardens.[24] By the early 19th century, however, gardening at The Woodlands became increasingly specialized, and Hamilton employed a number of professional seedsmen, nurserymen, and botanists to oversee the landscaping and gardening activities at his estate, including John Lyon, Frederick Pursh, and John McAran.[25]

Scholars have noted how, influenced by 18th-century aesthetic theory that privileged principles of visual continuity, Hamilton carefully coordinated interior and exterior environments at The Woodlands to produce the experience of a unified whole.[26] The construction of scenic vistas and “circuits,” such as walks and drives, integrated the house and other structures on the property into an overall landscape design.[27] Likewise, the house was carefully designed in relation to the surrounding landscape, with axial sight lines providing dramatic vistas of the grounds, river, and outlying countryside. Inside the mansion, the ground floor consisted of “a complex enfilade of public rooms composed in dynamic shapes and proportions,” according to Jacobs, that provided multiple ways to circulate through the space.[28] The “experience . . . of constantly changing forms” in the interior mirrored “the experience of winding paths and surprising vistas in the garden,” as Richard J. Betts has argued. Large bay windows permitted views from the house of the city and surrounding countryside to the east and of Hamilton’s greenhouse and the Schuylkill River to the west. Windows along the mansion’s north-south axis provided views of the park to the north and the garden and river to the south. Mirrors affixed to both sides of interior doors and window shutters “repeated and reflected interior or landscape scenes,” according to Long, depending on whether they were closed or opened.[29] One late 18th-century visitor described the effect of the mirrors as being “like a fairy scene,” giving the impression that the vista was “twice the extent” (view text). Much as beautiful plants and statues adorned the grounds, architectural details and works of art decorated the mansion’s interior. For the poet “Laura,” “flow’ry treasures of each distant land” in The Woodlands’ gardens delighted her eye in much the same way that “the living canvas” on the walls of the mansion did once inside (view text).[30]

Although the house and grounds were visually woven together, as Long has observed, utilitarian spaces were “intentionally concealed from view” in such a way that kept servants largely separated from Hamilton and his visitors while they enjoyed the mansion, garden, and lawn.[31] Wunsch has argued that Hamilton’s design for The Woodlands aligned with a larger “trend toward Romanticism [which] fostered an image of unmediated communion with nature that necessarily obscured the human systems on which ‘country life’ depended.”[32] Domestic servants moved through the mansion using an enclosed staircase that connected the basement with the two floors of living spaces above, while a masonry screen and hedges described by Drayton kept the servants’ passages between the mansion’s cellar and the garden and stable yard completely “out of sight” (view text).[33]

As early as 1803, Hamilton began to make plans to subdivide parts of the estate for a housing development he intended to name “the village of Hamilton,” although these plans were never realized.[34] Following Hamilton’s death in 1813, The Woodlands—then comprising about 385 acres—passed to Hamilton’s nephew James Hamilton (d. 1817). After James’s death four years later, Hamilton’s heirs found the expense of maintaining The Woodlands difficult to sustain. The mansion house was rented out by 1826, suggesting that the Hamilton family had already moved out of the property by this time. The following year, The Woodlands was sold at a sheriff’s sale to Henry Beckett, a distant Hamilton in-law who was acting on behalf of members of the Hamilton family. Beckett then almost immediately sold the mansion and surrounding 91 acres out of the Hamilton family to Thomas Flemming in 1828.[35] In 1831 the developer Thomas Mitchell purchased the mansion and surrounding property and built wharves across the estate’s waterfront. Although Mitchell also planned to build a canal through the property, he abandoned that idea in favor of developing the estate as a rural cemetery.[36] In 1840, the property was acquired by four trustees of The Woodlands and, in 1843, 75 acres were transferred to the Woodlands Cemetery Company.[37]

The Woodlands Cemetery Company’s directors honored Hamilton’s legacy by preserving the mansion (which, from the 1850s, was used as an office) and allowing access to Hamilton’s gardens and greenhouse. The Philadelphia seedsman Henry Augustus Dreer (1818–1873) was even permitted to operate his nursery business at The Woodlands from 1839 until about 1850.[38] In the winter of 1841–42, the surveyor Philip M. Price (1802–1870), who had already contributed to a number of other rural cemetery projects, devised a plan for The Woodlands that combined aspects of both the geometric style and the natural style of landscape design. The cemetery was divided into sections bounded by winding roads, with each section designed individually. The earliest sections to be developed were located in the inner core of the grounds, and laid out with alleys, diagonal paths, and curving walks to provide access to individual graves and family plots. The outer subdivisions of the cemetery were initially left as undeveloped green space. Avenues named for trees (occasionally corresponding with those planted along them) provided major access routes. Hamilton’s greenhouse was demolished in 1854 to make room for sheds for horses and carriages, and the mansion and stable-carriage house are the only Hamilton-era buildings that remain at the site of The Woodlands today.[39]

—Lacey Baradel and Robyn Asleson

Texts

- Hamilton, William, April 1779, in a letter to William Tilghman Jr. (quoted in Wunsch 2004: 23)[40]

- “I have just been making some considerable Improvements at the Woodlands, and I long to have you see them. . . From the scarcity of Fence Nails, High prices and Difficulty of getting Labourers I have been obliged to throw 100 acres on the back of my House, into only one Enclosure which although not inconvenient has never [had a?] handsome Effect. You may recollect the Ground is Hill & Dale Woodland and plain and therefore well enough calculated to make a small park, and I am endeavoring to give it as much as possible a parkish Look. My Lawn too I expect will shine this summer, it already looks elegantly. And so it ought, you'll say, when you are told the manuring it this last Winter has cost me £1500.” back up to History

- Hamilton, William, April 1779, in a letter to William Tilghman Jr. (quoted in Long 1991: 83)[41]

- “As to Philadelphia, I never go there without business calls me. Do you remember how anxious I was two or three years ago to have a peep at the Town, thro the Central Wood. ‘Twas then an object of my regard, but at present I do cordially hate it, that altho the prospect of it lately open’d by the total removal of the Wood is a most commanding one, & would at any other time have been admired, it is now absolutely disgusting to me. Judge by this what must be the Frame of my Mind.” back up to History

- Hamilton, William, April 1779, in a letter to William Tilghman Jr. (quoted in Long 1991: 84)[41]

- “The necessity I am under of repairing in some Degree, the Damage my Estate has sustained, gives me constant employment, & obliges me to stir about a good deal, and as it leaves less time for Thought, is I believe of considerable Service to my Health which I am persuaded would otherwise suffer, from my Reflexions on past and present Scenes.”

- Washington, George, January 15, 1784, in a letter from Mount Vernon to William Hamilton[42]

- “If I recollect right, I heard you say when I had the pleasure of seeing you in Philadelphia, that you were about a Floor composed of a Cement which was to answer the purpose of Flagstones or Tiles, and that you proposed to variegate the colour of the squares in the manner of the former.

- “As I have a long open Gallery in Front of my House to which I want to give a Stone, or some other kind of Floor which will stand the weather; I would thank you for information respecting the Success of your experiment—with such directions and observations (if you think the method will answer) as would enable me to execute my purpose. If any of the component parts are scarce & expensive, please to note it, & where they are to be obtained—& whether all seasons will do for the admixture of the Composition.

- “I will make no apology for the liberty I take by this request, as I persuade myself you will not think it much trouble to comply with it.”

- Hamilton, William, February 20, 1784, in a letter from Bush Hill to George Washington[43]

- “I engaged a person of the name of Turner, newly arrived from England, to do some stucco work at Bush Hill. While he was at the work I frequently talk’d with him about the different compositions now so much used in England particularly that for covering floors, Roofs, & fronts of Houses. He professed to understand the method of preparing & applying it & wished me to encourage him in giving a Specimen. To this, I at length consented, and he undertook to make a variegated floor in my Green House, one for an open portico on the front of my House on the Schuylkill, and to cover the flats of two Bow Windows. . . I have enquired of Mr. Vaughan & several other english [sic] gentlemen who say great things of it.”

- Washington, George, April 6, 1784, in a letter from Mount Vernon to William Hamilton[44]

- “I have been favored with your letter of the 20th of Feb. & pray you to accept my thanks for the information contained in it.

- “I expect to be in Phila. the first of May, but if, in the meanwhile, you should be perfectly satisfied of the skill of Mr Turner and the efficiency of his work you would add to the favor already conferred on me by desiring him not to be engaged further than to yourself until I see him.

- “I have a large room which I intend to finish in Stucco & Plaister of Paris—besides this I have a Piazza in front of my House (open & exposed to the weather) of 100 feet by 12 or 14 which I want to give a Floor to of stone or a cement which will be proof against wet & frost——and I am, as you were, plagued with leaks at a Cupulo &ca which requires a skilful artist to stop. These, altogether, would afford Mr Turner a good job, whilst the proper execution of them would render me an acceptable Service.”

- Parke, Thomas, April 27, 1785, in a letter from Philadelphia, PA, to Humphry Marshall (quoted in Harshberger 1929: 278)[45]

- “W. Hamilton has sent a number of curious Flowering Shrubs & Forest Trees to be transplanted at his Seat on the Schuylkill.” back up to History

- Hamilton, William, September 24, 1785, in a letter from England to Dr. Thomas Parke (quoted in Betts 1979: 224–25)[46]

- “Having resolved on my return in the Spring I am daily looking forward to the arrangements for making my situation convenient and agreable. Some addition to the House, a stable & other offices are immediately necessary at the Woodlands, and as I have most severely felt the consequences of having workmen at extravagant prices, I mean to take from hence some who will engage with me for a certain number of years on moderate terms, & if the remittances will admit I will also purchase in this Country every kind of material by which any thing can be saved. Some indeed there are that will depend on taste, and as I am vain enough to like my own as well as that of any one, cannot be so well got by anybody else when my back is turn’d. In order to take time by the forelock, Mr. Bob Barclay has been so good as to write for me to Glasgow, & had order’d out two or three stone quarriers the expence of whose passages & c. will probably have to be paid by you. I know not yet the terms but will give you the earliest information. You will on their arrival fix them at the Woodlands & employ them during the winter at the quarry where the stones were raised for building the Bridge over the mill creek as I think that the best kind of stone. By the way I wish to have an experiment made with some of our stone & beg you will be so kind as to send me a block from that very quarry of about 12 Inches square & six Inches thick as also a block of the chester stone of the same size. You must be sensible too that I can get a first rate gardiner to go with me on very moderate terms compared with what that branch at present costs me & I shall not fail to suit myself.” back up to History

- Hamilton, William, September 30, 1785, in a letter from England to his secretary, Benjamin Hays Smith (quoted in Betts 1979: 225)[46]

- “Having observed with attention the nature, variety & extent of the plantations [in England] of shrubs trees & fruits & consequently admired them, I shall (if God grant me a safe return to my own country) endeavour to make it [the Woodlands] smile in the same useful & beautiful manner. To take time by the forelock, every preparation should immediately be made by Mr. Thompson who is on the spot, & I have no doubt you will assist him to the utmost of your power. The first thing to be set about is a good nursery for trees, shrubs, flowers, fruit, &c. of every kind. I do desire therefore that seeds in large quantities may be directly sown of the white flowering locus, the sweet or aromatic birch, the chestnut oak, horse chestnuts, chincapins. . . .

- ”When you write again, inform me of the Dimensions of the Sideboard I bought of Mr. Penn: not only the size of the Board, but of the frame as to width, length, & height I wish to know what can stand under it.

- “Step also the Diameter of the circle or ring that ends in the Ice House Hill & tell me the space from one to the other side of the walk & of the Ha Ha. I am at a loss to determine the number of feet from the west wall of the House to the East Wall of the Green House at the Woodlands.” back up to History

- Hamilton, William, November 2, 1785, in a letter from England to Dr. Thomas Parke (quoted in Betts 1979: 225)[46]

- “As I can by no means afford to live in Bush Hill, I shall be under the necessity of adding to the House & building Offices at the Woodlands. Altho the state of my finances will not allow me to do much at present & the improvements must be gradual, It will be proper however to fix on some general plan for the whole & according as I have wherewithal while I am on the spot mean to procure whatever materials in the way of finishing & furnishing may be here purchased on a saving plan. The more I can do in this way the better as besides lessning the Expence There will be a great savings of time. I mention this to prove to you how very useful it will be to me for you to remit whatever Cash can be spared from my American occasions. I have the vanity to think I shall be thereby enable to introduce many conveniences & improvements that will be useful to my country as well as myself.”

- G., L., June 15, [1788?], in a letter to her sister Eliza (quoted in Betts 1979: 216–17)[46]

- “the moment you enter the grounds you discover all the neatness of the possessor, the road leading to the house is delightful, you wind round a small declivity through a clear wood consisting almost entirely of young trees & through the opening valley you have a distant view of the City—The house is planned with a great deal of taste, the front is divided into a spacious hall with a room at each end, the back part is composed of a large dining-room, separated by an entry leading from the hall to the back-door, from a very handsome room, which, when finished will form a complete oval—The prospect from every room is enchanting, as you enter the hall you have a view of a remarkably fine lawn, beyond that, the bridge over which people are constantly passing, the rough ground opposite to Gray’s, four or five windings of the Schuylkill, the intermediate country & the Delaware terminated by the blue mist of the Jersey shore—on one side you see distinctly the City & the surrounding country, on the opposite end, another view of the Schuylkill and the green-house—at the back the eye is refreshed with the sight of the most beautiful trees.—The whole of this is heightened by mirror doors which when closed repeats the landscape & has a very fine effect it appears, indeed, like a fairy scene, another effect produced from them is, that when you are at one end of the house & look through them, you not only see the whole length, but that, being reflected by these glass doors gives you the idea of its being twice the extent.

- “Mr. Hamilton was remarkably polite—he took us round his walks which are planted on each side with the most beautiful & curious flowers & shrubs they are in some parts enclosed with the Lombardy poplar except here & there openings are left to give you a view of some fine trees or beautiful prospect beyond & in others, shaded by arbours of the wild grape, or clumps of large trees under which are placed seats where you may rest yourself & enjoy the cool air—when you arrive at the bottom of the lawn along the borders of the river you find quite a natural walk which takes the form of the grounds entirely shaded with trees & the greatest profusion of grapes which perfumes the air in a most delightful manner, its fragrance resembles that of the Minionet, a little further on, you come to a charming spring, some part of the ground is hollowed out where Mr. Hamilton is going to form a grotto, he has already collected some shells; from this place you might have a view of the mill back of Gray’s, but as the owner will not be induced to part with it although he has been offerred £100 per acre for 50 acres Mr. Hamilton has entirely shut it out—the walk terminates at the Green-house which is very large the front is ornamented with the greatest quantity of the most flourishing jesamine & honeysuckles in full bloom that I have ever seen—the plants are all removed to a place back of the Green house where they are ranged in the most beautiful order, they are so numerous that we had time to see only a very small part, every spring each plant is removed to a different spot—

- “It would take several days to be perfectly acquainted with the various beauties of this charming place to take in the whole of its beauties, you ought to view it at different hours of the day & particularly at moon light, so that you can form but an inadequate idea of its charms from a visit of two hours, such, however, as I have I will venture to give you & though you may not be able from my description to form an exact picture of it, still you will have room to exercise your imagination & supply the deficiencies & if you derive amusement it will afford me pleasure.” back up to History

- Hamilton, William, [July] 21, 1788, in a letter from Yorktown, PA, to his secretary, Benjamin Hays Smith (quoted in Hamilton and Smith 1905: 152)[47]

- “I have a letter from Mr Child by which I clearly see matters go but ill at the Woodlands. The plaisterer came not to work for several days after that he appointed which must greatly delay the finishing of those rooms immediately wanted. . .”

- Hamilton, William, October 22, 1788, in a letter from Lancaster, PA, to his secretary, Benjamin Hays Smith (quoted in Hamilton and Smith 1905: 153)[47]

- “If Mr Child pays so little attention to my other directions I must in my own defence immediately give up all thought of removing to the Woodlands during this year of our Lord. Should that be the case, I shall as soon as I return Home discharge every workman & shut up the House untill the spring as I am determined not to be subject to the inconvenience of leaving my family during the short days to attend any workmen whatever.”

- Hamilton, William, 1789, in a letter to his secretary, Benjamin Hays Smith (quoted in Madsen 1988: A4)[48]

- “In my Hurry at the time of coming off from Home I omitted to put in the ground the exotic Bulbous roots & as I gave no direction to Hilton respecting them they may suffer more especially as they were all taken out of the pots & left dry on the Back flue of the Hot House.”

- Hamilton, William, May 2, 1789, in a letter to his secretary, Benjamin Hays Smith (quoted in Hamilton and Smith 1905: 154)[47]

- “You must not fail to go to the Woodlands every day for more reasons than one & take a memm of the occurrences of each day. Hilton should [make] some mark immediately on ye pot of each newly transplanted exotic, so as to prevent its being disturbed on my return. The aloes water’d twice a week gently, and all the Carolina & newly imported English plants should be frequently refresh’d with water. I would have you mark all the polianthos snow drops in the Bord'rs of the Ice H. Hill walk & direct George to attend to the ripening of the seeds so as to save them. As soon as George has done the above all the exotics should be arranged according to their sizes in the way I directed particularly the pots on the shelves, the melon boxes may be taken into the garden & the plants taken out & transplanted on forming the 3d leaf into good hills & labell’d. The Rose Bush Box should be removed into ye shade behind the Hot House there to remain during the summer. The Exotic yard if I may so call it & all the space between the green H & the shop should be made clean & neat as I have no doubt there will be visitors to view them.”

- Hamilton, William, September 27, 1789, in a letter to his secretary, Benjamin Hays Smith (quoted in Madsen 1988: A6, A7)[48]

- “The first moment after Hilton has finished weeding in the Garden as I directed he should set about weeding the terrace walk as I will endeavour to have it gravelld during the winter. . .”

- Hamilton, William, October 3, 1789, in a letter from Lancaster, PA, to his secretary, Benjamin Hays Smith (quoted in Hamilton and Smith 1905: 157)[47]

- “Mr Child told me he would not fail to remind you of getting McIlvee out to mend the hot house. Unless this is done the West India plants cannot be safe. . . .I think it will be well enough for you to go to Bartrams & know from him what Hot House plants he intended for me and also his prices for each of the plants in ye enclosed list. Its possible Mrs Rulen and her daughter will sail for the West Indies before my return. In case Miss Markoe comes to the Woodlands I wish Ann & Peggy would beg her to think of me in the flower seed way when she is at Santa Cruz. Those of all fragrant and beautiful plants will be agreeable, particularly ye Jasmines. . . .”

- Hamilton, William, October 12, 1789, in a letter from Lancaster, PA, to his secretary, Benjamin Hays Smith (quoted in Betts 1979: 234)[49]

- “You say the ploughman at the Woodlands will want from me 9 bushels of seed. Can this be all my share for the 33 or 34 acres of lawn. You mention not the Stable scantling. . . .

- “If the Borders are already done & all other matters finish’d as before directed by me for Hilton &c, They may as well set to clear the stones away from the spot where the stable is to stand so as to have every thing ready for beginning on my return. If Hilton, Willy & Bob cannot yet be spared for this Business, I would advise you to get a couple of strong trusty labourers & employ them about it & discharge them as soon as 'tis effectually done. Mr. Child knows where the stable is to stand with its front due east. . .”

- Hamilton, William, October 12, 1789, in a letter to his secretary, Benjamin Hays Smith (quoted in Madsen 1988: A6, A7)[48]

- “When the terrace is weeded, the two Borders leading from the House to the Ice House Hill should be cleaned. . .”

- Hamilton, William, June 12, 1790, in a letter from Lancaster, PA, to his secretary, Benjamin Hays Smith (quoted in Hamilton and Smith 1905: 258–259)[50]

- “Common sense would point out the necessity of my having constant information respecting the grass grounds at Bush Hill and at the Woodlands which must be now nearly in a state for mowing. . . . It would have been an agreeable circumstance to me to have heard the large sumachs & lombardy poplars as well as the magnolias have not been neglected. The immense number of seeds from foreign countries must certainly have produced (if attended to) many curious plants. The casheros, conocarpus Arnott’s walking plants &c which I planted out the day before I left home have I hope been taken care of. I should however been glad to have heard of their fate as well as respecting the Gooseberries and Antwerp Raspberries given me by Dr Parke. After the immense pains I took in removing the exotics to the north front of the House by way of experiment, & the Hurry of coming away preventing my arranging them, you will naturally suppose me anxious to know the success as to ye plants and the effect as to appearance in ye approach & also their security from cattle. The curious exotic cuttings & those of the Franklinea I did not believe it possible for even you to be inattentive to. . . . I wished you to be very active on the arrival of the India ships, in finding out whether any passengers had seeds &c. . . . I find Bartram has Cape plants & seeds but hear not a word of your having got any for me. By the way, I should be glad if you had given the reason of Bartrams ill Humour when you called. He certainly had no cause for displeasure respecting his plants left under my care during the winter. . . . Mr Wikoff promised me some seeds of a cucumber six feet long.”

- Hamilton, William, June 12, 1790, in a letter to his secretary, Benjamin Hays Smith (quoted in Madsen 1988: A6, A7)[48]

- “The newly planted trees & shrubs along the terrace respecting which you know me to be so anxious, may be alive or dead for ought I know.”

- Hamilton, William, June 12, 1790, in a letter to his secretary, Benjamin Hays Smith (quoted in Madsen 1989: 21)[51]

- “Pray have you had a plenty of peas & Beans? Have you got Strawberries! are they good have the celery plants put into the ground which was promised by the gardener Morris—How many thousand cabbage plants have been planted out. The seeds must have been wretchedly bad if they have not produced thousands of plants. But if they faild a small matter would purchase many pray are the pumpkins sowed or the potatoes planted I am thus inquisitive because I am really ignorant with respect to the state of all these things.”

- Hamilton, William, June 6, 1791, in a letter from Lancaster, PA, to his secretary, Benjamin Hays Smith (quoted in Hamilton and Smith 1905: 261)[50]

- “The plants sent by Mr. Von Rohr are valuable & I hope George will particularly attend to them. The palm is called Cornon from Cayenne & along side of him as von Rohr says is a young cacao or chocolate plant. The last particularly is alive I hope. The Hibiscus tiliacens in ye 2d Box, is the mahoe tree, & the Roots are the pancratium maritimum. The flower pot contains an anacardium occidentale. As to the cereus cutting I would not have it divided but planted in a heavy pot of such a size as not to be over-potted & placed in such a situation as to be properly supported & secured from being blown over by the wind.”

- Twining, Thomas, May 30, 1795, diary entry describing The Woodlands (1894: 163)[52]

- “Mr. Hamilton’s seat was quite in the English style. The house was surrounded by extensive grounds tastefully laid out along the right bank of the Schuylkyl. After dinner the company walked upon this bank, whose slope to the water was planted with a variety of wild and cultivated shrubs. On the other side of the gravel walk which bordered these shrubberies was an extensive lawn which fronted the principal windows of the house. As the company, broken into small parties a few yards from each other, were walking slowing along this walk, a snake, supposed to be of a venomous kind, crossed from the bushes, and disappeared in the grass on our left. Some of the company endeavoring to find it with their sticks, Mr. Hamilton said he had a gardener remarkable in respect to snakes, and the man being called soon discovered it.”

- Hamilton, William, November 23, 1796, in a letter from The Woodlands to Humphry Marshall (quoted in Darlington 1849: 578)[53]

- “I am much obliged to you for the seeds you were so good as to send me, of the Pavia, and of the Podophyllum or Jeffersonia.

- “When you were last here it was so late, and you were of course so much hurried, as to prevent your deriving any satisfaction in viewing my exotics. I hope when you come next to Philadelphia, that you will allot one whole day, at least, for the Woodlands. It will not only give me real pleasure to have your company, but I am persuaded it will afford some amusement to yourself.

- “Your nephew [ Moses Marshall ] did me the favour of calling, the other day; but he, too, was in a hurry, and had little opportunity of satisfying his curiosity. I flatter myself, however, that during his short stay he saw enough to induce him to repeat his visit. The sooner this happens, the more agreeable it will be to me.

- “When I was at your house, a year ago, I observed several matters in the gardening way, different from any in my possession. Being desirous to make my collection as general as possible, I beg to know if you have, by layers, or any other mode, sufficiently increased any of the following kinds so as to be able, with convenience, to spare a plant of each of them, viz.:—Ledum palustre, Carolina Rhamnus, Azalea coccinea, Mimosa Intsia, and Laurus Borbonia. Any of them would be agreeable to me; as also would be a plant, or seeds Hippophae Canadensis, Aralia hispida, Spiraea nova from the western country; Tussilago Petasites, Polymnia tetragonotheca, Hydrophyllum Canadense, H. Virginicum, Polygala Senega, P. biflora, Napoea scabra dioica, Talinum, a nondescript Sedum from the west, somewhat like the Telephium, two kinds of a genus supposed, by Dr. MARSHALL, to be between Uvularia and Convallaria [probably the Streptopus, of MICHAUX, which the MARSHALLS proposed to call Bartonia], and Rubia Tinctorum. I should also be obliged to you for a few seeds of your Calycanthus, Spigelia Marilandica, Tormentil from Italy, and two of your Oaks with ovate entire leaves.”

- Hamilton, William, March 6, 1797, in a letter from The Woodlands to George Washington[54]

- “Having been told you intend leaving Town tomorrow I have sent the Clod of Grass, together with a plant of the upright Italian Myrtle & one of the Box leaved Myrtle for Mrs Washington. . .

- “I have also sent half of the Seeds of the persian Grass saved last Season at the Woodl[an]ds.”

- Niemcewicz, Julian Ursyn, March 24, 1798, journal entry describing The Woodlands (1965: 52–53)[55]

- “On returning we saw the house of Hamilton. It is the Villa Borghese of Philad. Its situation is one of the most beautiful that one could see. Placed at a bend in the Skulkill, it overlooks the whole breadth of its limpid waters, while from the other side one sees clearly all the city of Philadelphia. The house is spacious, arranged and decorated in a style rare in America: there were pictures, medallions, bronzes, etc. All this would be nothing elsewhere; but here the eye, deprived for a long time of all that resembles art, dwells with pleasure on all which reminds one of it. With what satisfaction did I not contemplate a good copy of the Venus by Titian of Florence. Hamilton was not there. . . . His farm contains 200 to 300 acres of very mediocre land as is all that in the environs of Philad, but which cultivated could produce something. He leaves it fallow; he is interested only in his house, his hothouse and his Madeira. He carries his fastidiousness about the countryside to such a point that he is in a dreadful humor when one comes to visit it during low tide.”

- La Rochefoucauld Liancourt, François-Alexandre-Frédéric, duc de, 1799 (quoted in Madsen 1988: B3)[48]

- “You pass the Schuylkill at Gray’s-Ferry, the road to which runs below Woodlands, the seat of Mr. William Hamilton: it stands high, and is seen upon an eminence from the opposite side of the river.”

- da Costa Pereira Furtado de Mendonça, Hipólito José, February 24, 1799, in a diary entry describing The Woodlands (quoted in Smith 1954: 94–95)[56]

- “Today I dined with Mr. Hamilton, who lives on the other side of the Schuylkill. He is a learned man very much taken with the subject of botany. In his hothouse he has many plants from China and Brazil, including 15 species of the sensitive plant and many other kinds of mimosa. He had one variety of sugar cane that comes from an island in the Pacific and which is already being cultivated in the West Indies. It gives twice as much sugar as the regular plants and requires no more labor. He promised me seeds, etc., etc. I will make a catalogue of all the plants he has. He also has tea trees, jambo trees, guavas, etc.”

- da Costa Pereira Furtado de Mendonça, Hipólito José, March 6, 1799, in a diary entry describing The Woodlands (quoted in Smith 1954: 97)[56]

- “I went to Mr. Hamilton’s hothouse, where he awaited me with a catalogue of questions and then wrote down the answers as I gave them to him. . . .”

- da Costa Pereira Furtado de Mendonça, Hipólito José, March 26, 1799, in a diary entry describing The Woodlands (quoted in Smith 1954: 99)[56]

- “Today I saw in Mr. Hamilton’s hothouse two more varieties of mimosa, which I sketched.”

- da Costa Pereira Furtado de Mendonça, Hipólito José, March 26, 1799, in a diary entry describing The Woodlands (quoted in Smith 1954: 99)[56]

- “Today I dined with Mr. Hamilton, who sent me a precious collection of seeds”

- Hamilton, William, May 3, 1799, in a letter from The Woodlands to Humphry Marshall (Darlington 1849: 579–80)[53]

- “Doctor Parke informs me you were lately in Philadelphia. Had it been convenient to you to call at the Woodlands, I should have had great pleasure in seeing you. . . .

- “I do not know how your garden may have fared during this truly long and severe winter, which has occasioned the loss of several valuable ones in mine; amongst which are the Wise Briar [probably Schrankia uncinata, Willd.; Mimosa Intsia, Walt.] and Hibiscus speciosus, which I got from you. The plants, also, of Podophyllum diphyllum, which I raised last year, from seeds I received from your kindness, have, I fear, been all destroyed. They have not shown themselves above ground this spring. A tree, too (the only one I had of Juglans Pacane, or Illinois Hickory), which I raised twenty-five years ago from seed, is entirely killed.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, April 22, 1800, in a letter from Philadelphia, PA, to William Hamilton[57]

- “Among the many botanical curiosities you were so good as to shew me the other day, I forgot to ask if you had the Dionaea muscipula, and whether it produces a seed with you. if it does, I should be very much disposed to trespass on your liberality so far as to ask a few seeds of that, as also of the Acacia Nilotica, or Farnesiana whichever you have.”

- Hamilton, William, January 16, 1803, in a letter from The Woodlands to Thomas Jefferson[58]

- “Mr. Hamilton presents his respectful compliments to the President, & with great pleasure, sends him a few seeds of the mimosa farnesiana, being all he saved during the last year. Lest these should not vegetate, Mr. H. will, as soon as they ripen, forward some of the present years growth to the president, who will confer a favor on him, in naming any seeds or plants he may wish to have from the Woodlands collection.”

- Hosack, David, July 25, 1803, in a letter to Dr. Thomas Parke, regarding the greenhouses at the Elgin Botanic Garden and The Woodlands (quoted in Long 1991: 144)[59]

- “I duly received the plans of Mr. Hamiltons green and hot houses. My greenhouse [exclusive of the hothouses] is now finishing— it will not differ very individually from Mr. Hamiltons. It is 62 feet long 23 deep—and 20 high in the clear. I shall heat it by flues, they will run under the stays so they will not be seen— my walks will be spacious hot houses are for next summer’s operation. My collection of plants is yet small. I have written to my friends in Europe and in the East and West Indies for their plants. I will also collect the native productions of North and South America. What medical plants can Mr. Bartram supply— request him to send me a catalogue. I hope William Hamilton will have duplicates of rare and valuable plants — I will supply him anything I possess.” back up to History

- Cutler, Manasseh, November 22, 1803, in a letter to his daughter Mrs. Torrey, describing The Woodlands (1888: 2:144–46)[60]

- “Since you are quite a gardener, I will mention a visit I made, on my journey, near Philadelphia, to a garden, which in many respects exceeds any in America. It is at the country-seat of Mr. Hamilton, a gentleman of excellent taste and great property. . . As soon as we had dined, he [Mr. Pickering] called me aside, and told me he had been acquainted with Mr. Hamilton, who was noted for his hospitality, and who lived but half a mile up the river, where he did not doubt we should be kindly entertained. We immediately set out, and arrived about an hour before sunset. His seat is on an eminence, which forms on its summit an extended plain, at the junction of two large rivers.

- “Near the point of land a superb but ancient house built of stone is situated. In the front, which commends an extensive and most enchanting prospect, is a piazza, supported on large pillars, and furnished with chairs and sofas, like an elegant room. Here we found Mr. H., at his ease, smoking his cigar. . . We then walked over the pleasure grounds in front and a little back of the house. It is formed into walks, in every direction, with borders and flowering shrubs and trees. Between are lawns of green grass, frequently mowed to make them convenient for walking, and at different distances numerous copse of native trees, interspersed with artificial groves, which are set with trees collected from all parts of the world. I soon found the fatigue of walking too great for me, though the enjoyments, in a measure, drove away the pain. . . We then took a turn in the gardens and the green-houses. In the gardens, though ornamented with almost all the flowers and vegetables the earth affords, I was not able to walk long. The green-houses, which occupy a prodigious space of ground, I can not pretend to describe. Every part was crowded with trees and plants from the hot climates, and such as I had never seen, all the spices, the tea-plant in full perfection; in short, he assured us there was not a rare plant in Europe, Asia, or Africa, many from China and the islands in the South Seas, none, of which he had obtained any account, which he had not procured.

- “By this time it was so dark that no object could be distinctly examined. We retired to the house. The table was spread with decanters of different wines, and tea was served.

- “Immediately after, another table was loaded with large botanical books, containing the most excellent drawings of plants, such as I never could have conceived. He is himself an excellent botanist. . . When we turned to rare plants, one of the gardeners would be called, and sent with lanterns to the green-house to fetch me a specimen to compare with it. This was done perhaps twenty times.

- “Between 10 and 11 an elegant table was spread, with, I believe, not less than twenty covers. After supper, we turned again to the drawings, and at one we retired to bed. Our lodging was in the same style, and I had an excellent night’s sleep”

- Jefferson, Thomas, November 6, 1805, in a letter from Washington to William Hamilton[61]

- “I happen to have two papers of seeds which Capt Lewis inclosed to me in a letter, and which I gladly consign over to you, as I shall any thing else which may fall into my hands & be worthy your acceptance. one of these is of the Mandan tobacco, a very singular species uncommonly weak & probably suitable for segars. the other had no ticket but I believe it is a plant used by the Indians with extraordinary success for Curing the bite of the rattle snake & other venomous animals. I send also some seeds of the Winter melon which I recieved from Malta. some were planted here the last season, but too early. they were so ripe before the time of gathering (before the first frost) that all rotted but one which is stil sound & firm & we hope will keep some time. experience alone will fix the time of planting them in our climate, so that a little before frost they may not be so ripe as to rot, & still ripe enough to advance after gathering in the process of maturation or mellowing as fruit does. I hope you will find it worthy a place in your kitchen garden.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, July 31, 1806, in a letter to William Hamilton[62]

- “I remember seeing in your greenhouse a plant of a couple of feet height in a pot the fragrance of which (from it’s gummy bud if I recollect rightly) was peculiarly agreeable to me and you were so kind as to remark that it required only a greenhouse, and that you would furnish me one when I should be in a situation to preserve it. but it’s name has entirely escaped me & I cannot suppose you can recollect or conjecture in your vast collection what particular plant this might be. I must acquiese therefore in a privation which my own defect of memory has produced, unless indeed I could some of these days make an impromptu visit to Phila. & recognise it myself at the Woodlands.

- “Should a journey at any time promise improvement to it [Hamilton’s health], there is no one on which you would be received with more pleasure than at Monticello. Should I be there you will have an opportunity of indulging on a new field some of the taste which has made the Woodlands the only rival which I have known in America to what may be seen in England.

- “Thither without doubt we are to go for models in this art. Their sunless climate has permitted them to adopt what is certainly a beauty of the very first order in landscape. Their canvas is of open ground, variegated with clumps of trees distributed with taste. They need no more of wood than will serve to embrace a lawn or a glade. But under the beaming, constant and almost vertical sun of Virginia, shade is our Elysium. In the absence of this no beauty of the eye can be enjoyed. This organ must yield it’s gratification to that of the other senses; without the hope of any equivalent to the beauty relinquished. The only substitute I have been able to imagine is this. Let your ground be covered with trees of the loftiest stature. Trim up their bodies as high as the constitution & form of the tree will bear, but so as that their tops shall still unite & yeild dense shade. A wood, so open below, will have nearly the appearance of open grounds. Then, when in the open ground you would plant a clump of trees, place a thicket of shrubs presenting a hemisphere the crown of which shall distinctly show itself under the branches of the trees. This may be effected by a due selection & arrangement of the shrubs, & will I think offer a group not much inferior to that of trees. The thickets may be varied too by making some of them of evergreens altogether, our red cedar made to grow in a bush, evergreen privet, pyrocanthus, Kalmia, Scotch broom. Holly would be elegant but it does not grow in my part of the country.

- “You will be sensible by this time of the truth of my information that my views are turned so steadfastly homeward that the subject runs away with me whenever I get on it. I sat down to thank you for kindnesses received, & to bespeak permission to ask further contributions from your collection & I have written you a treatise on gardening generally, in which art lessons would come with more justice from you to me.” back up to History

- |Drayton, Charles, November 2, 1806, describing The Woodlands (1806: 49, 53–58)[63]

- “Dined at Mr. Hamilton’s, at his elegant seat about 3 miles from Philadelphia

- “I saw two Knacks, one for drying plants; the other an extensive measure, fit for the pocket. The first is a nest of boxes, the bottom of which are formed by tacking on a coarse linnen, that will not transmit sand, on a light frame, that is 1 1/2 or 2 inches deep. Only the uppermost box has a removable cover of wood as the rest are covers for those below—but the lowest box has its bottom of wood; to sustain the weight of so many boxes that are filled, each, with sand one inch deep. The wooden bottom & the cover, are pierced with many gimlet holes, for the transmission of air & moisture. The specimen of the plant being placed between two papers, is laid on the surface of sand, & then a box with sand is laid on it. There it lays till it is dried. The lower box, stands on 4 low feet, that air may pass through it;—& it has 2 handles, whereby the whole mass of boxes may be removed together.

- “The Approach, its road, woods, lawn & clumps, are laid out with much taste & ingenuity. Also the location of the Stables; with a Yard between the house, stables, lawn of approach or park, & the pleasure ground or garden.

- “The Fences separating the Park-lawn from the Garden on one hand, & the office yard on the other, are 4 ft. 6 high. The former are made with posts & lathes—the latter with posts, rails & boards. They are concealed with evergreeens hedge—of juniper I think. A common post & rail fence, [not in sight from the house,] winds from the public road gate, & joins to the garden fence, which is a double sloped ditch, with a low fence of posts & 3 rails. They seemed insufficient—at least for turbulent horses or even Sheep. The park lawn is not in good order, for lack of being fed upon. Its fences where it is not visible from the house, is of common posts & rails.

- “The Garden consists of a large verdant lawn surrounded by a belt of walk, & shrubbery for some distance. The outer side of the walk is adorned here & there, by scattered forest trees, thick & thin. It is bounded, partly as is described—partly by the Schuylkill & a creek exhibiting a Mill & where it is scarcely noticed, by a common post & rail. The walk is said to be a mile long—perhaps it is something less. One is led into the garden from the portico, to the east or lefthand. or from the park, by a small gate contiguous to the house, traversing this walk, one sees many beauties of the landscape—also a fine statue, symbol of Winter, & age,—& a spacious Conservatory about 200 yards to the West of the Mansion.

- “The Conservatory consists of a green house, & 2 hot houses—one being at each end of it. The green house may be about 50 feet long. The front only is glazed. Scaffolds are erected, one higher than another, on which the plants in pots or tubs are placed—so that it is representing the declivity of a mountain. At each end are step-ladders for the purpose of going on each stage to water the plants—& to a walk at the back-wall. On the floor a walk of 5 or 6 feet extends along the glazed wall & at each end a door opens into an Hot house—so that a long walk extends in one line along the stove walls of the houses & the glazed wall of the green house.

- “The Hot houses, they may extend in front, I suppose, 40 feet each. They have a wall heated by flues—& 3 glazed walls & a glazed roof each. In the center, a frame of wood is raised about 2 1/2 feet high, & occupying the whole area except leaving a passage along by the walls. In the flue wall, or adjoining, is a cistern for tropic aquatic plants. Within the frame, is composed a hot bed; into which the pots & tubs with plants, are plunged. This Conservatory is said to be equal to any in Europe. It contains between 7 & 8000 plants. To this, the Professor of botany is permitted to resort, with his Pupils occasionally.

- “As the position of many plants require external exposure in the Summer season that also is contrived with much ingenuity & beauty.

- “There are 2 large oval grass plats in front of the Conservatory—& 2 behind. Holes are nicely made in these, to receive the pots & tubs with their plants, even to their rims. The tallest are placed in the centre, & decreasing to the verge. Thus they represent a miniature hill clothed with choice vegetation.

- “The Stable Yard, tho contiguous to the house, is perfectly concealed from it, the Lawn, & the Garden. The mode of concealment from the 2 latter, has been mentioned under the article Fence. It remains to describe the former at [or contiguous to] the side of the house near to the front angle is a piece of masonry [which extends out, equal to the bow-window, & joins it—its cover is flat—it covers or screens the entrance to Cellar,] & is as high as the base of the principal floor bow windows. From the Cellar one enters under the bow window & into this Screen, which is about 6 or 7 feet square. Through these, we enter a narrow area, & ascend some few Steps [close to this side of the house,] into the garden—& thro the other opening we ascend a paved winding slope, which spreads as it ascends, into the yard. This sloping passage being a segment of a circle, & its two outer walls concealed by loose hedges, & by the projection of the flat roofed Screen of masonry, keeps the yard, & I believe the whole passage out of sight from the house—but certainly from the garden & park lawn. See the plan of the Grounds [Fig. 4].

- “The Stables, & sheds, form the 3rd side of this three sided yard—The stables are seen from the front door of the house, over the hedge that screens the Yard.

- “The kitchen garden & Hort. yard/Orchyard, which I did not see, are, I suppose behind the Stables, & adjacent.” back up to History

- Jefferson, Thomas, March 22, 1807, in a letter from Washington to William Hamilton[64]

- “It is with great pleasure that, at the request of Govenor Lewis, I send you the seeds now inclosed, being a part of the Botanical fruits of his journey across the continent: I cannot but hope that some of them will be found to add useful or agreeable varieties to what we now possess. these, with the descriptions of plants, which, not being in seed at the time, he could not bring, will add considerably to our Botanical possessions. . . . I send a similar packet to mr McMahon, to take the chance of a double treatment. in confiding these public deposits to your & his hands, I am sure I make the best possible disposition of them.”

- Niemcewicz, Julian Ursyn, April 1807, describing The Woodlands (1965: 290)[55]

- “I spent Sunday with Mr. Hamilton, owner of Wood-land, the famous residence near Philadelphia. The collection of foreign plants and bushes gathered from all three parts of the world, is the most numerous and beautiful which an individual may own. He has some fine pictures most of them signed by famous painters. The situation of the place amidst dark oaks and groves is strangely beautiful; before it lies Philadelphia and the Schuylkill river escaping in the distance in a wavy line.”

- Birch, William Russell, 1808, The Country Seats of the United States of North America (1808: n.p.)[65]

- “This noble demesne has long been the pride of Pennsylvania. The beauties of nature and the rarities of art, not more than the hospitality of the owner, attract to it many visitors. It is charmingly situated on the winding Schuylkill and commands one of the most superb water scenes that can be imagined. The ground is laid out in good taste. There are a Hot house and green house containing a collection in the horticultural department, unequalled perhaps in the Unites States. Paintings & c. of the first master embellish the interior of the house and do credit to Mr. Wm. Hamilton, as a man of refined taste.” [Fig. 5]

- Jefferson, Thomas, July 14, 1808, in a letter to Monsieur de la Cépèd (1944: 373)[66]

- “In the meantime, the plants of which he [Governor Lewis] brought seeds, have been very successfully raised in the botanical garden of Mr. Hamilton of the Woodlands, and by Mr. McMahon, a gardener of Philadelphia.”

- Laura, February 1809, original poetry published in Port Folio about The Woodlands (1809: 180–81)[67]

- “To view thy wonders, ROME, I used to sigh,

- “To breathe beneath thy pure transparent sky,

- “Thy pictures, statues, lofty domes to see,

- “And own thy far-spread fame surpass’d in thee;

- “Till late, invited by the Woodland’s shades,

- “I stray’d among its green, embower’d glades,

- “Where bright the wave of winding Schuylkill glides,

- “And Peace, with Hamilton and Taste, resides.

- “Rear’d by his care, unnumber’d balmy sweets,

- “The gladden’d eye in gay confusion meets.

- “The flow'ry treasures of each distant land,

- “Collected, cherish’d by his fostering hand;

- “And all the produce of the varying year,

- “Profusely scattered at his wish appear.

- “Led on by Fancy’s secret, magic call,

- “I reach the mansion, I ascend the hall;

- “What fairy forms I see around me rise!

- “What charms, what beauties strike my raptur’d eyes!

- “On every side, the living canvas speaks;

- “A god pursues, the flying maiden shrieks;

- “Or Night,[68] with starry robe and silver bow,

- “Sheds her mild lustre on the calm below.

- “Then, while within the Woodland’s fair domain,

- “The Muses rove, and Classic pleasures reign;

- “For distant climes no longer will I sigh,

- “No longer wish to distant realms to fly;

- “But often seek these charming, verdant glades,

- “But often wander in these fragrant shades;

- “Oft mark the place, where little Naiads mourn,

- “With ceaseless sighs, around their Shenstone’s urn;

- “Where bright the wave of winding Schuylkill glides,

- “And Peace, with Hamilton and Taste, resides.”

- back up to History

- Jefferson, Thomas, May 7, 1809, in a letter from Monticello to William Hamilton[69]

- “I have a grandson, Thos J. Randolph, now at Philadelphia, attending the Botanical lectures of Doctr Barton, and who will continue there only until the end of the present course. altho’ I know that your goodness has indulged Dr Barton with permission to avail himself of your collection of plants for the purpose of instructing his pupils, yet as my grandson has a peculiar fondness for that branch of the knolege of nature, & would wish, in vacant hours to pursue it alone, I am led to ask for him a permission of occasional entrance into your gardens, under such restrictions as you may think proper. I have so much experience of his entire discretion as to be able with confidence to assure you that nothing will recieve injury from his hands. I have desired him to deliver this to you himself, as well for the honor of personally presenting his respects to you, as of giving you assurances of the discreet use he will make of your indulgence. I have pressed upon him also to study well the style of your pleasure grounds, as the chastest model of gardening which I have ever seen out of England.”

- Martin, William Dickinson, May 20, 1809, journal entry describing The Woodlands (1959: 34–36)[70]

- “The grounds which occupy an extent of nearly ten acres are laid out with uncommon taste, and in the construction of the mansion house, solidity & elegance are combined. . .

- “If thus far the eye has been pleased from viewing these fine productions of art, how much more will it be gratified when contemplating the prospect that bursts upon the sight from the Centre of the Saloon! The verdant mead, the spacious lawn, Schuylkill’s lucid stream, the floating bridge, the waves here checked by the projecting rock, then overshadowed by inclining trees, until, by meandering and luxuriant folds, the winding waters lead the entranced eye to Delaware’s proud river, on whose swollen bosom rich merchant ships are seen, descending with the vast surplus of our fertile soil, or others mounting heavily the stream, deep laden with the wealth of foreign climes.

- “Such are, in part, the beauties of this delightful scenery, & had the view terminated with highlands or some o'er-towering mountain, no prospect could have been more perfect.

- “The attention is next arrested by the grounds, in the arrangement of which, the hand of taste, is every-where visible. Foreign trees, from China, Italy, & Turkey, chosen for their superior foliage, or balmy odours, are diffusely scattered, or mingled with sweet shrubs & plants, bordering the walks: and as the fragrant path winds round, openings, judiciously exposed, such as the situation of the land best admits, diversify the scene. At one spot, the city with its lofty spire appears: at another a vast expanse of water; at a third, verdure & water, happily blending form a complete landscape: and at another where the champaign Country is broken with inequality of ground. Now at the descent is seen a creek o'er hung with rocky fragments, & shaded by the thick forest’s gloom. Ascending thence towards the Western side of the Mansion, the green house presents itself to view, & displays to the observer, a scene than which, nothing that has preceded it can excite more admiration. The front, including the hot house on each side, measures One Hundred & forty feet, & it contains nearly ten thousand plants, out of which number may be reckoned between five & six thousand of different species, procured at much trouble & expense from many remote parts of the globe, from South America, The Cape of Good Hope, the Brazils, Botany Bay, Japan, East & West Indies etc., etc. This collection for the beauty & variety of its exotics, surpasses any thing of the kind on this Continent: and among many other rare productions to be seen are, the bread fruit tree, cinnamon, All spice, pepper, mangoes of different kinds, sago, coffee from Bengal, Arabia & the West Indies: tea, green & bohea, mahogany, magnolias, Japan rose, rose apples, cherimolia one of the most esteemed fruits of Mexico, bamboo, Indian god-tree, iron tree of China, ginger, alea fragrants, & several varieties of the sugar cane, five species of which are from Otaheite. To this green House so richly stored too much praise can hardly be given. The curious person views it with delight, & the Naturalist quits it with regret.

- “. . . Altho’ much has been done to beautify this delightful seat, much still remains to be done, for the perfecting it in all the capabilities which nature in her boundless profusion has bestowed. These improvements it is said, fill up the leisure moments, & form the most agreeable occupation of its possessor: and that he may long live to pursue this refined pleasure, must be the wish of the public at large, for to them, so much liberality has even been shown in the free access to the house & grounds, that of the enjoyment of the fruits of his care, & cultivated taste, it may be said truly, Non sibi sed aliis.” back up to History

- Anonymous, obituary for William Hamilton, June 8, 1813 (Poulson’s American Daily Advertiser)

- “His noble mansion was for many years the resort of a very numerous circle of friends and acquaintances, attracted by the affability of his manners, and a frankness of hospitality, peculiar to himself, which made even strangers feel at once welcome, easy and happy in his society.”

- Watson, Joshua Rowley, June 30, 1816, describing The Woodlands (quoted in Foster 1997: 296)[71]

- “We drove over to the Woodlands to call on Mr Hamilton. It is a very good house on a large scale, the approach well laid out, and the Trees and Shrubberies fine—The view from it, looking down the Schuylkill is beautiful—near the house in a second ground, is the Lower, or Log Bridge, before noticed,—in the distance you see the river Delawar, Fort Mifling, the Vessels passing up & down that great river, and the Jersy shore finishes the picture.”

- Anonymous, 1821, describing an exhibition of an aloe plant (Plough Boy: 30)[72]

- [June 6] “It is believed that, but two of those plants have come to perfection in the United States. One was at Springbury, the seat of William Penn, near Bush Hill. This plant flowered in 1777. From it the late Mr. William Hamilton got a sucker, which he was fortunate enough to rear, and it flowered at the Woodlands, in the year 1804.” back up to History

- Bernhard, Karl, Duke of Saxe-Weimar, 1825, describing The Woodlands and Lemon Hill (1828: 1:141)[73]

- “Woodlands has more the appearance of an English park than Mr. Pratt’s country-seat; the dwelling house is large and provided with two balconies, from both of which there is a very fine view, especially of the Schuylkill and floating bridge. Inside of the dwelling there is a handsome collection of pictures; several of them are of the Dutch school. What particularly struck me was a female figure, in entire dishabelle, laying on her back, with half-lifted eyes expressive of exquisite pleasure. There were also orange trees and hot-houses, superintended by a French gardener.”

- Hooker, William Jackson, July 1829 (1829: 157)[74]

- “In 1802, Mr. Pursh had the charge of the extensive gardens of W. Hamilton, Esq. called the Woodlands, which having, immediately previous, been under the charge of Mr. Lyon, an Englishman, and an eminent collector, were found to be enriched with a number of new and valuable plants; and Mr. Pursh affirms, that through Mr. Lyon’s means, more rare and novel plants have been introduced from thence to Europe than through any other channel whatever. The herbarium, as well as the living collection of Lyon, was of great use to Mr. Pursh; and the plants described by him, from specimens seen only in that herbarium, are numerous.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1844 (1844: 31, 33)[75]

- “Woodlands, the seat of the Hamilton family, near Philadelphia, was, so long ago as 1805, highly celebrated for its gardening beauties. The refined taste and the wealth of its accomplished owner, were freely lavished in its improvement and embellishment; and at a time when the introduction of rare exotics was attended with a vast deal of risk and trouble, the extensive green-houses and orangeries of this seat, contained all the richest treasures of the exotic flora, and among other excellent gardeners employed, was the distinguished botanist [Frederick] Pursh, whose enthusiastic taste in his favorite science was promoted and aided by Mr. [William] Hamilton. The extensive pleasure grounds were judiciously planted, singly and in groups, with a great variety of the finest species of trees. The attention of the visitor to this place is now arrested by two very large specimens of that curious tree, the Japanese Ginkgo (Salisburia), 60 to 70 feet high, perhaps the finest in Europe or America, by the noble magnolias, and the rich park-like appearance of some of the plantations of the finest native and foreign oaks. From the recent unhealthiness of this portion of the Schuylkill, Woodlands has fallen into decay, but there can be no question that it was, for a long time, the most tasteful and beautiful residence in America. . . .

- “This [Waltham House, near Boston], and Woodlands, were the two best specimens of the modern style, as Judge [Richard] Peters’ seat, Lemon Hill, and Clermont, were of the ancient style, in the earliest period of Landscape Gardening among us.”

Images

William Hamilton, Plan for Kitchen Garden and Orchard, June 1790.

James Peller Malcolm, The Woodlands From the Bridge at Gray’s Ferry, c. 1792–94, in Beth C. Wees and Medill H. Harvey, Early American Silver in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (2013), 259.

William Groombridge, The Woodlands, the Seat of William Hamilton, Esq., 1793. Santa Barbara Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. Sterling Morton for the Preston Morton Collection.

Charles Drayton I, Sketch of the Woodlands, Seat of William Hamilton, in the Diary of Charles Drayton I, 1806.

Pavel Petrovich Svinin, View of Morrisville, General Moreau’s Country House in Pennsylvania, Possibly The Woodlands, Pennsylvania, 1811—c. 1813.

Firm of Joseph Stubbs, decoration after William Birch, Dish with view of The Woodlands, c. 1825.

Notes

- ↑ For the full chain of ownership of the land between 1684 and 1828, see James A. Jacobs, The Woodlands (revised documentation), Historic American Buildings Survey PA-1125 (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 2002–2003), 10–16, view on Zotero; and from 1828 to 1955, see Aaron V. Wunsch, Woodlands Cemetery, Historic American Landscapes Survey PA-5 (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 2004), 4–7, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jacobs 2002–2003, 16 and 23, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Timothy Preston Long, “The Woodlands: A ‘Matchless Place,’” (master’s thesis, University of Pennsylvania, 1991), 68, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Most of the form of Hamilton’s original house was “concealed or destroyed” by Hamilton’s renovation in the late 1780s. Jacobs 2002–2003, 2, view on Zotero. For a discussion of what is known regarding the construction date of the original house, see James A. Jacobs, “William Hamilton and the Woodlands: A Construction of Refinement in Philadelphia,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 130, no. 2 (April 2006): 189–93, view on Zotero; Jacobs 2002–2003, 19–25, 27, view on Zotero. According to Jacobs, sources suggest that no more than three open porticoes predated Hamilton’s in all of British North America (28).

- ↑ Hamilton purchased additional land and was gifted 179 acres by his uncle James Hamilton (1715?–1783) in March 1776. Jacobs 2002–2003, 10 and 24, view on Zotero.

- ↑ During the American Revolution, Hamilton was arrested twice. Following the first arrest in September 1778, Hamilton was tried and acquitted of high treason on October 17. After his second arrest in 1779, Hamilton served a brief prison sentence and paid a large fine but was eventually allowed to return home and remain in Pennsylvania for the duration of the conflict. Catherine E. Kelly, Republic of Taste: Art, Politics, and Everyday Life in Early America(Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016), 124–25, view on Zotero; Long 1991, 83, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Wunsch 2004, 23–24, view on Zotero. To put the £1500 sum in perspective, Long notes that “many skilled labourers made less than £200 annually.” Long 1991, 85, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Long 1991, 87, view on Zotero.

- ↑ According to Nevell’s accounts for 1784, he provided Hamilton with “some Estracts from Sundry Plans in [his] Possession.” Jacobs 2002–2003, 3, view on Zotero.

- ↑ In 1784, Hamilton purchased a variety of building materials (plaster, bricks, boards, and nails) and paid laborers for glazing, carpentry work, and the laying of six hearths at The Woodlands. He traveled to England to settle financial matters relating to the estate of his uncle, James Hamilton, who had died the previous year. Jacobs 2002–2003, 3, 30, and 50, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Letters written by Hamilton during this time indicate that he visited several counties in England known for their landscape gardens, including Buckinghamshire, Wiltshire, Oxfordshire, and Hertfordshire. See Wunsch 2004, 8, view on Zotero.