Springettsbury

Overview

Alternate Names: The Proprietor’s Garden

Site Dates: 1682–c. 1753

Site Owner(s): William Penn 1644–1718; Thomas Penn 1702–1775; John Penn 1760–1834; Robert Morris 1734–1806;

Associated People: James Alexander 1778, gardener;

Location: Philadelphipa, PA · 39° 57' 45.22" N, 75° 10' 25.57" W

Condition: Demolished

Keywords: Eminence; Fence; Greenhouse; Grove; Hedge; Hothouse; Labyrinth; Meadow; Park; Parterre; Pleasure ground/Pleasure garden; Seat; Terrace/Slope; View/Vista; Walk; Wall; Wilderness; Wood/Woods

See also: The Hills, Lemon Hill

Springettsbury, a property owned by successive generations of the Penn family, overlooked the Schuylkill River on the northern outskirts of Philadelphia. It was the site of the first ornamental pleasure garden in Pennsylvania and initiated the fashion for garden-villa retreats on the banks of the Schuylkill.[1]

History

William Penn, the English Quaker Proprietor of Pennsylvania, first visited the colony in 1682. In addition to establishing Pennsbury, a manor house and garden some distance from Philadelphia, Penn carved out Springettsbury as a suburban estate immediately adjacent to the city.[2] With the intention of producing wine as a source of revenue, Penn imported grape vines from Bordeaux and, in 1683, employed the French Huguenot refugee and vigneron André Doz to lay out a vineyard on a 200-acre section of Springettsbury that became known as Vineyard Hill. Penn soon returned to England but continued to send European vines to Doz, who also experimented with the cultivation of indigenous American grapes.[3] Wine production proved unsuccessful and, just prior to his death in 1718, Penn gave a large tract of Springettsbury land that included Vineyard Hill to Jonathan Dickinson.[4] Penn's family later gave another portion of the estate to their legal counselor, Andrew Hamilton (c.1676–1741), which he enlarged through subsequent purchases to form the country seat Bush Hill.[5]

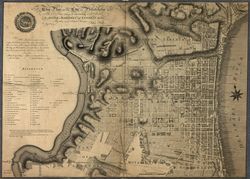

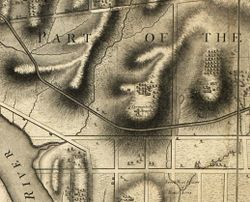

Penn's son Thomas (1702–1775) arrived in Philadelphia in 1732 and assumed the role of Proprietor. Although he persisted in his father’s attempt to create a wine-producing vineyard at Springettsbury,[6] Thomas Penn did not conceive of the estate as predominantly a working farm. Rather, he developed it as a weekend and summer retreat in the manner of an English suburban villa.[7] His modest brick house, erected between 1737 and 1740, appears in a map of 1796 [Fig. 1 and 2]. It stood at the center of an extensive landscape composed in the “ancient style” that was just passing out of fashion in England, including long, gravel walks lined with trees or hedges. There was also a wilderness, a labyrinth (the earliest known in the colony) fashioned of hornbeam, a fishpond, and a garden, divided in two by a privet hedge. Enclosed by a board fence with ornamental gates, the garden (commonly known as “The Proprietor’s Garden”) boasted gravel walks, parterres, spruce topiary, and painted wooden seats.[8] Penn’s sister Margaret Freame (1704–1751) described the gardens at Springettsbury as her “Chief amusement” in November 1735,[9] and around 1740 she erected a “pretty bricked Green House”—one of the first in Pennsylvania—to replace the “small room in the garden [with] a German stove” in which oranges imported from England had previously been wintered.[10] During the warmer months, lime trees were displayed in a quincunx pattern in the garden, where lemons and citrons also flourished.[11] Other fruit (including apples, pears, peaches, cherries, figs, and grapes) grew in the orchard and vineyard.[12] Peter Collinson provided many of the imported plants, among them grape vines, jasmine, horse chestnuts, cornelian cherries, pyracantha, boxwood, and honeysuckle.[13] In 1737 Collinson orchestrated an introduction between Thomas Penn and John Bartram, who was developing a botanic garden and commercial nursery several miles away on the banks of the lower Schuylkill River. Penn loaned Bartram his copy of Mark Catesby's The Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands, and some years later commissioned Bartram “to procure some Curiosities for him” on his travels.[14]

One of the more fashionable elements of the Springettsbury landscape was the deer park (again, the first known example in the colony), which Penn filled with deer imported from England, as well as with wild turkey and pheasants.[15] Following his return to England in 1741, Penn expressed a desire to introduce changes at Springettsbury in keeping with the rising English taste for a naturalistic "modern style" in garden design. These included creating a number of framed vistas, replacing the “palisadoe” at the end of a walk with a ha-ha, and removing the quickset hedge to open up the fields.[16] Nothing seems to have come of Bartram’s proposal in 1743 that Penn provide him with an “annual salary worth while to furnish his walks with all ye natural production of trees shrubs & plants which grow in our four governments.”[17] Concerned by the theft of fruit from Springettsbury in 1746, Penn made plans to erect a wall separating his property from Bush Hill, noting: “When the rest of the Ground is well paled round I shal [sic] hope to be secure.”[18]

James Alexander (d. 1778) served as Penn’s head gardener at Springettsbury. The first professional gardener in Pennsylvania who can be identified, he is best known for discovering the so-called “Alexander grape” (a naturally produced American-European hybrid) around 1740 in the woods near Vineyard Hill.[19] Long after Thomas Penn’s return to England in 1741, Alexander continued to maintain the property, often sending American fruits, nuts, seeds, and plants (including magnolia, azalea, laurel, and rhododendron) for Penn to share with friends or keep for his English estate, Stoke Park.[20] Alexander also operated a commercial business exporting seeds and plants to clients in England, rivaling even his principal competitor, John Bartram, in his ability to meet the demand for increasingly rare and unusual specimens.[21] At the American Philosophical Society (which elected him a member in 1768 and a curator in 1772 and 1773), Alexander demonstrated some of his botanical experiments and served on committees dealing with subjects ranging from astronomy, to natural history, to husbandry.[22] Visitors to Springettsbury noted the many scientific instruments he employed there, including an orrery, a solar microscope, a telescope, and “a curious thermometer of spirits and mercury.”[23]

Both Deborah Norris Logan and Elizabeth Drinker recalled the “curious aloe” (originally planted by James Alexander and subsequently cultivated by his successor, the enslaved African American gardener Virgil Warder) that attracted curious crowds to Springettsbury when it finally bloomed in August 1778 (view text).[24] Although Springettsbury by that time had become a favorite destination for Philadelphia pleasure-seekers, the Penn family took minimal interest in the estate. Thomas Penn’s nephew, John Penn (1729–1795), settled in Philadelphia in 1765 but preferred to live at his new Palladian manor house, Landsdowne, on the opposite side of the river. Thomas’s son, also named John Penn (1760–1834), followed suit, building his house, The Solitude, across the river in 1785. As the Penn family sold off portions of the Springettsbury estate, many lots were purchased by the financier and land speculator Robert Morris who was consolidating his landholdings in the Northern Liberties of Philadelphia. In 1770 he acquired Vineyard Hill, which he redeveloped as The Hills. In 1780 he leased the old brick house at Springettsbury as a summer retreat.[25] According to John Jay’s sister-in-law, Catherine Livingston, a frequent guest of the family, Morris “repaired and enlarged the buildings and converted the greenhouse into a dining room which far exceeds their expectations in beauty and convenience.”[26] Although a fire in 1784 apparently rendered the house uninhabitable,[27] Morris purchased the property in 1787 and five years later had a canal dug along the southern and western border of the original Springettsbury estate. A fire in 1807 entirely consumed the old brick house, and in 1815 Deborah Logan described the greenhouse as a “ruin” and the garden as overgrown.[28]

—Robyn Asleson

Texts

- Pastorius, Francis Daniel, 1700, Circumstantial Geographical Description of Pennsylvania, (quoted in Myers 1912, 13:398)[29]

- “As I on August 25 [1684] was dining with William Penn, a single root of barley was brought in which had grown in a garden here and had fifty grains upon it. The abovementioned William Penn has a fine vineyard of French vines planted; its growth is a pleasure to behold and brought into my reflections, as I looked upon it, the fifteenth chapter of John.”

- Lloyd, David, October 2, 1686 (quoted in Myers 1912, 13: 291)[29]

- “The Governours Vineyard goes on very well, the Grapes I have tasted of; which in fifteen Months are come to maturity.”

- Hockley, Richard, May 27, 1742, letter to Thomas Penn (1903: 428)[30]

- “I have accepted of your kind offer of Lodging with Mr Lardner as it will save me some expence, and have been twice at Springetsbury, but both Places appear not to me as usual and instead of affording me any real satisfaction rather damps my Spirits, both ye Gardens & Vineyard are I think in tolerable good order but still there wants a superior Eye over it, your directions to Jacob & James [Alexander] will be complyed with, and there’s a fine show of Grapes, the Orange trees flourish most delightfully, but am afraid the Quicksett hedge will not answer your expectation. . . .

- “James desires you wou’d be pleased to send over two Stone rowlers [rollers] for the Garden those made in this place will not do neither answer the expence and imagines they will come cheaper from London they must be two feet 8 inches in length one 18 ye 15 in diameter, all the Flowers I brought with me flourish exceedingly but ye Hautboy Strawberries are al [sic] dead and ‘tis very difficult I believe to get them safe here, they were in the same box and had ye same Care taken of them and what is the reason they don’t do I cant account for.”

- Hockley, Richard, June 27, 1742, letter to Thomas Penn (1903: 435)[30]

- “Mr Peters has bought Mr Taylor’s scantling and ‘tis carried to ye Hill and put under a Shedd, he has a notion you intend to build a house there for your self to live in before that at Springettsbury is built I believe he is mistaken and told him so, as you propose to build soon it wou’d be proper I believe that Bricks shoud be made against you come but Mr Peters knows nothing about it and there’s no orders given to make any nor won’t be untill he hears from you, and the Ground all round Springettsbury has been tryed but not fitt to make bricks with this was done before Mr Steels death and nothing has been thought on it since. I wrote you sometime ago that there was a fine shew of Grapes at Springettsbury and the bunches hang very thick but there’s either a blight or some Insect that destroys some one third others one half of the Clusters and yet the leaves and shoots looks as fresh and flourishing as may be, this being Sunday I propose to walk out by my self to Springettsbury and see if I can with all the reflection that I am Master of compose my mind a little if I shoud it will be something new to me.”

- Hockley, Richard, July 14, 1742, letter to Thomas Penn (1904: 30)[31]

- “[T]he Grapes at Springetsbury is intirely demolished and can't conceive the meaning of it, the Orange trees some of them are full of little flatt Insects, and James does not know what to do with them, ye trees on each side ye long walk wants to be shrowded very much, and hope you'l order it to be done in ye fall.”

- Hockley, Richard, September 18, 1742, letter to Thomas Penn (1904: 37)[31]

- “I have sent you 3 dozn of oranges & Leamons from Springetttsbury pack’d up in a Box directed for you. Mr Lardner & James [Alexander] were afraid they wou’d not keep, however I have run the risque, the Governour has had a dozn Already & am afraid the Trees have been Pilfer’d. They are in very good order, & every thing Else except the fences round Springettsbury & am Sorry to find James not the Person I cou’d wish & think him blame worthy in Several respects.”

- Smith, John, November 3, 1745, diary entry (1877: 131)[32]

- “On our way thither we stopped to view the proprietor’s green-house, which at this season is a very agreeable sight; the oranges, lemons and citrons were, some green, some ripe, some in blossom.”

- Penn, Thomas, September 18, 1746, letter to Richard Hockley (1916: 224–25)[33]

- “I received a Box of Fruit from Springetsberry, but they were not so good as the others sent in the Fall; as they were ripened chiefly by the Summers Sun. I am sorry the people are so Licentious as to break into the Garden at Springetsberry, and believe when I come over I shal build a Wall between that and Mr Hamiltons Land from Mr Jones’s, which will make it very inconvenient for them to visit us, and when the rest of the Ground is well paled round I shal hope to be secure. I ordered Mr Lardner to Let only my own twelve Acres of Meadow, which was let before my departure to a Dutchman, the piece of Meadow belonging to us in Mr Turners Road is sufficient for Springetsberry and I think I gave no orders to let that. I am quite weary of the Vineyard for which only Jacob is kept at £35 a year but your last Letter gives mee some hopes that it may produce some thing, if that does not succeed when I come over. I shal much lessen it. I shal consent to their cutting down the Wood between the Vineyard and the Field, but not that on the west side of it yet, that may be thinned, and would have any that is fit split into rough pales and laid by. [T]he privit hedge that grows between the two Gardens may be taken upp if it grows into the Walks.”

- Thomas Penn, January 29, 1754, letter to John Penn (quoted in McLean and Reinberger 1999: 36)[34]

- “I desire to know whether you often visit Springettsbury, or amuse yourself with gardening, which is a pleasing employment, when it does not interrupt the more weighty concerns in which a man is engaged, and which I found an agreeable recreation after perhaps disagreeable business.”

- Stiles, Ezra, September 30, 1754, diary entry (“Ezra Stiles in Philadelphia, 1754”: 375)[35]

- “After breakfast Messrs Jos. & Wm Shippen accompanied us to Springsbury, where passing a long spacious walk, set on each side with trees, on the summit of a gradual ascent, we saw the proprietor’s house, & walkt in the gardens, where besides the beautiful walk, ornamented with evergreens, we saw fruit trees with plenty of fruit, some green, some ripe, & some in the blossom on the same trees. The fruit was oranges, limes, limons, & citrons. In the hot house was a curious thermometer of spirits & mercury. Spruce hedges cut into beautiful figures, &c., all forming the most agreeable variety, & even regular confusion & disorder.

- “We then walk thro’ a spacious way into the wood behind & adjoyning to the gardens, the whole scene most happily accommodated for solitude and rural contemplation.”

- Fisher, Daniel, May 25, 1755 (1893: 267–68)[36]

- “I walked about Two miles out of Town in the “Proprietors’ Garden,”…. The proprietors’ tho’ much smaller [than Bush Hill], was laid out with more judgment, tho’ it seemed to have been pretty much neglected. A pretty pleasure garden, the trees of which now hardly visible, a small wilderness, and other shades, shows that the contriver was not without judgment; but what to me surpassed everything of the kind I had seen in America was a pretty bricked Green House, out of which was disposed (now) very properly in the Pleasure Garden a good many Orange, Lemon, and Citron Trees in great (268) perfection loaded with abundance of Fruit and some of each sort seemingly then ripe.

- The House here is but small, built of Brick, with a small Kitchen, etc, justly contrived rather for a small than a numerous Family. It is pleasantly situated on an eminence with a gradual descent—over a small Valley—to a handsome level Road cut through a wood, affording an agreeable vista of near Two miles. On the left hand the slope, descending from the house, is a neat little Park, tho’ I am told there are no Deer in it.”

- Drinker, Elizabeth, September 7, 1778, diary entry (1994: 80)[37]

- “[We] took a walk this Afternoon to Springsbury [sic] to see the Aloes Tree—stop’d in our return at Bush-Hill and walk’d in the Garden,—came home after Sun Set, very much tired.”

- Livingston, Kitty, July 10, 1780, letter to Mrs. John Jay (Jay 1890–93, 1:376)[38]

- “In our last distresses from the invasion of the British troops [during the winter of 1779–1780], Mr. and Mrs. Morris sent for me to come and reside with them. . . . They have at present a delightful situation at Springsberry [sic]. Mr. Morris has repaired and enlarged the buildings and converted the greenhouse into a dining room which far exceeds their expectations in beauty and convenience.”

- Hiltzheimer, Jacob, March 20, 1784, diary entry (1898: 62)[39]

- “Sent my man with three horses up to the Honorable Robert Morris’ country seat, Springettsbury, to bring back the fire engine belonging to the Amicable Fire Company, which was taken there yesterday, when the house was on fire.”

- Drinker, Elizabeth, October 15, 1807, diary entry (1889: 410)[40]

- “The House at Springettsbury formerly belonging to the Penn family Was last night consumed by fire.”

- Logan, Deborah Norris, September 27, 1815, diary entry (quoted in White 2008: 18–19)[41]

- “Passing one day by the old manor of Springetsbury [sic], I greatly desired to stop and look at the remains of the garden. . . The little greenhouse is now a ruin. In my youth an aloe was in flower, and crowds flocked out of town every fine day for many weeks to see the curiosity. Some of the fine labyrinths and hedges broke loose from the restraint of the sheers, and grown up behind the greenhouse, form a dark grove of evergreens. Broom and some other European plants still grow wild. . . (and I think it was the prettiest old-fashioned garden that I was ever in).”

- Logan, Deborah Norris, October 10, 1826, diary entry (quoted in White 2008: 19)[41]

- “The Gardens of Springetsbury [sic] were in full beauty in my youth, and were really very agreeable after the old fashion, with Parterres, Gravelled Walks, a Labyrinth of Horn-beam and a little wilderness—And the Green house, under the Superintendence of Old Virgil the Gardener, produced a flowering Aloe which almost half the town went to see, produced a comfortable Revenue to the old man—Soon after the house was burned down by accident; and now quantities of the yellow Blossoms of Broom in spring time mark the place. . . ‘where once the garden smiled.’” back up to History

- Logan, Deborah Norris, February 13, 1832, diary entry (quoted in Weber 1996: 45)[42]

- “There is a Report of the Committee of the Horticultural Society in the ‘Register’ for last week in which is displayed a great ignorance of the former taste for Gardening amongst us when it states, that Mr. Pepper’s Green house, originally built by Dr. Barbon, was the first Green house built in Pennsylvania; this is not so.—The Greenhouse at Springetsbury, built by Margaret Freame daughter of William Penn, was the first.”

Images

Notes

- ↑ Elizabeth McLean and Mark Reinberger, "Springettsbury: A Lost Estate of the Penn Family,” Journal of the New England Garden History Society, 7 (fall 1999): 35, view on Zotero; Elizabeth McLean and Mark Reinberger, "Isaac Norris’s Fairhill: Architecture, Landscape, and Quaker Ideals in a Philadelphia Colonial Country Seat,” Winterthur Portfolio, 32 (Winter 1997), 273, view on Zotero.

- ↑ McLean and Reinberger 1999, 34,view on Zotero; Roach, April 1968, 178–79; William Henry Egle, An Illustrated History of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Civil, Political and Military: From Its Earliest Settlement to the Present Time (Philadelphia: E. M. Gardner, 1880), 1020, view on Zotero.

- ↑ McLean and Reinberger 1999, 41, view on Zotero; Thomas Pinney, A History of Wine in America: From the Beginnings to Prohibition (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989), 32–33, 101–2, view on Zotero; Frederick B. Tolles, “William Penn on Public and Private Affairs, 1686: An Important New Letter,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 80 (April 1956): 244, view on Zotero; Albert Cook Myers, ed., Narratives of Early Pennsylvania, West New Jersey, and Delaware, 1630–1707, Original Narratives of Early American History (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1912), 13: 227–28, view on Zotero; J. Thomas Scharf and Thompson Westcott, History of Philadelphia, 1609–1884, 3 vols. (Philadelphia: L. H. Everts & Co., 1884), 3:2281–82, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Scharf and Westcott 1884, 3:2282, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Fanning Watson and Willis P. Hazard, Annals of Philadelphia, and Pennsylvania, in the Olden Time, 3 vols. (Philadelphia: Edwin S. Stuart, 1884), 3:493, view on Zotero.

- ↑ McLean and Reinberger 1999, 41, view on Zotero; Richard Hockley, “Selected Letters from the Letter-Book of Richard Hockley, of Philadelphia, 1739–1742 (Concluded),” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 28 (1904): 435, view on Zotero; Richard Hockley, “Selected Letters from the Letter-Book of Richard Hockley, of Philadelphia, 1739–1742 (Continued),” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 27 (1903): 421–35, view on Zotero.

- ↑ McLean and Reinberger 1999, 34–35,view on Zotero.

- ↑ Sharon White, Vanished Gardens: Finding Nature in Philadelphia (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2008), 19 view on Zotero; McLean and Reinberger 1999, 37–40, view on Zotero; Hockley 1903, 428, view on Zotero; Thomas Penn, “Letters of Thomas Penn to Richard Hockley, 1746–1748,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 40 (1916): 225, view on Zotero; Daniel Fisher, “Extracts from the Diary of Daniel Fisher, 1755,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 17 (1893): 267–68, view on Zotero; “Ezra Stiles in Philadelphia, 1754,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 16 (1892): 375, view on Zotero; Watson and Hazard 1884, 3:400, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Howard M. Jenkins, The Family of William Penn, Founder of Pennsylvania, Ancestors and Descendants (Philadelphia: The author, 1899), 240, view on Zotero.

- ↑ White 2008, 19, view on Zotero; McLean and Reinberger 1999, 42, view on Zotero; Carmen Weber, “The Greenhouse Effect: Gender-Related Tradition in Eighteenth-Century Gardening,” in Landscape Archaeology: Reading and Interpreting the American Historical Landscape, ed. Rebecca Yamin and Karen Bescherer Metheny (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1996), 4, view on Zotero; Reinberger and McLean 1997, 262, view on Zotero; Fisher 1893, 267, view on Zotero.

- ↑ McLean and Reinberger 1999, 42, view on Zotero; Hockley 1903, 428, view on Zotero; Myers 1904, 71–72, view on Zotero; "Ezra Stiles in Philadelphia,” 1892, 375, view on Zotero; Fisher 1893, 267–268, view on Zotero.

- ↑ McLean and Reinberger 1999, 41, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Bartram, The Correspondence of John Bartram 1734–1777, ed. Edmund Berkeley and Dorothy Smith Berkeley (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1992), 64, 82, 108, 115, view on Zotero; White 2008, 14, view on Zotero; McLean and Reinberger 1999, 40–41,view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bartram 1992, 64, 94, 152, 219, view on Zotero.

- ↑ White 2008, 16, view on Zotero; Lorett Treese, Storm Gathering: The Penn Family and the American Revolution (University Park: Penn State Press, 1992), 23, view on Zotero; Penn 1916, 238, view on Zotero; Fisher 1893, 268, view on Zotero.

- ↑ McLean and Reinberger 1999, 39, 44, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bartram 1992, 217.

- ↑ Penn 1916, 224, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Pinney 1989, 84–85, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Whitfield J. Bell Jr., Patriot-Improvers: Biographical Sketches of Members of the American Philosophical Society, 3 vols. (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1997), 1: 476–77, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bartram 1992, 407, 410, 430, 513, view on Zotero; see also Mark Laird, The Flowering of the Landscape Garden: English Pleasure Grounds, 1720–1800 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999), 396–97, 78n, view on Zotero; Bell 1997, 1: 478, view on Zotero; Joseph Ewan, “Philadelphia Heritage: Plants and People,” in America’s Garden Legacy: A Taste for Pleasure, ed. George H. M. Lawrence (Philadelphia: The Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1978), 3, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bell 1997, 1:476–77, view on Zotero.

- ↑ White 2008, 22, view on Zotero; “Ezra Stiles in Philadelphia,” 1892, 375, view on Zotero; R. Morris Smith, The Burlington Smiths: A Family History (Philadelphia: Printed for the Author, 1877), 160, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Elizabeth Drinker, Extracts from the Journal of Elizabeth Drinker, from 1759 to 1807 A.D., ed. Henry D. Biddle (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company , 1889), 109, view on Zotero; White 2008, 18–19, view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Graham Sumner, Robert Morris: The Financier and the Finances of the American Revolution, 2 vols. (New York: Cosimo, Inc., 1891), 1:303 view on Zotero; Robert Morris, The Papers of Robert Morris, 1781–1784, ed. Elmer James Ferguson, 9 vols. (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1973), 1:113–14,192 view on Zotero; Watson and Hazard 1884, 2:479, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Kitty Livingston to Mrs. John Jay, July 10, 1780, quoted in John Jay, The Correspondence and Public Papers of John Jay, ed. Henry P. Johnston, 4 vols. (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1890–93), 1:376, view on Zotero.

- ↑ McLean and Reinberger 1999, 45 n46, view on Zotero; Drinker 1889, 152, view on Zotero; Jacob Hiltzheimer, Extracts from the Diary of Jacob Hiltzheimer of Philadelphia, 1765–1798, ed. Jacob Cox Parsons (Philadelphia: William F. Fell & Co., 1893), 62 view on Zotero; White 2008, 19, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Drinker 1889, 410, view on Zotero; White 2008, 18–19, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Myers, 1912, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Hockley 1903, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Hockley 1904, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Smith 1877, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Penn 1916 view on Zotero.

- ↑ McLean and Reinberger 1999, view on Zotero.

- ↑ “Ezra Stiles in Philadelphia, 1754,” view on Zotero.

- ↑ Fisher 1893, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Elizabeth Drinker, The Diary of Elizabeth Drinker: The Life Cycle of an Eighteenth-Century Woman, ed. Elaine Forman Crane (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1994), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jay 1890–93,view on Zotero.

- ↑ Hiltzheimer 1893, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Drinker 1889,view on Zotero.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 White 2008, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Weber 1996, view on Zotero.