Difference between revisions of "Obelisk"

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

The obelisk’s rich antique associations imbued it with symbolic significance. Its origins in Egypt, prominence in the Roman world, and, since the Renaissance, use in gardens and [[park]]s lent a vocabulary of the exotic and the historic to American landscape design. Several collected treatise citations recount the best-known examples of ancient obelisks, many of which have survived into the modern period. Excavations in Rome during the seventeenth century, for example, revealed dozens of Egyptian obelisks that were re-erected throughout the city. At the same time, modern obelisks ornamented French gardens such as Versailles. Many great gardens in Britain in the eighteenth century also featured obelisks: Castle Howard, Chiswick House, Holkham Hall, and Montacute House, to name a few.<ref>Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe, Susan Jellicoe, Patrick Goode, and Michael Lancaster, eds., ''The Oxford Companion to Gardens'' (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), 408, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/S392BPJ8/q/jellicoe view on Zotero].</ref> With the French invasion of Egypt in 1798, the taste for Egyptian statuary and styles increased and obelisks appeared more frequently as props in gardens.<ref>For information on the Egyptian style in America, see Richard G. Carrott, ''The Egyptian Revival: Its Sources, Monuments, and Meaning, 1808-1858'' (Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press, 1978), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/HC7PJUR7/q/egyptian view on Zotero].</ref> Thus the tradition of obelisks in European gardens and public spaces transmitted via literature, European designers, and American visitors abroad, was a significant influence on American garden practice. Both [[Ephraim Chambers]] (1741–43) and [[Noah Webster]] (1828) described the use of hieroglyphic inscriptions on obelisks that expressed the historic tradition from which the form derived. | The obelisk’s rich antique associations imbued it with symbolic significance. Its origins in Egypt, prominence in the Roman world, and, since the Renaissance, use in gardens and [[park]]s lent a vocabulary of the exotic and the historic to American landscape design. Several collected treatise citations recount the best-known examples of ancient obelisks, many of which have survived into the modern period. Excavations in Rome during the seventeenth century, for example, revealed dozens of Egyptian obelisks that were re-erected throughout the city. At the same time, modern obelisks ornamented French gardens such as Versailles. Many great gardens in Britain in the eighteenth century also featured obelisks: Castle Howard, Chiswick House, Holkham Hall, and Montacute House, to name a few.<ref>Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe, Susan Jellicoe, Patrick Goode, and Michael Lancaster, eds., ''The Oxford Companion to Gardens'' (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), 408, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/S392BPJ8/q/jellicoe view on Zotero].</ref> With the French invasion of Egypt in 1798, the taste for Egyptian statuary and styles increased and obelisks appeared more frequently as props in gardens.<ref>For information on the Egyptian style in America, see Richard G. Carrott, ''The Egyptian Revival: Its Sources, Monuments, and Meaning, 1808-1858'' (Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press, 1978), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/HC7PJUR7/q/egyptian view on Zotero].</ref> Thus the tradition of obelisks in European gardens and public spaces transmitted via literature, European designers, and American visitors abroad, was a significant influence on American garden practice. Both [[Ephraim Chambers]] (1741–43) and [[Noah Webster]] (1828) described the use of hieroglyphic inscriptions on obelisks that expressed the historic tradition from which the form derived. | ||

| − | In America, the choice of the obelisk for political commemoration in public spaces was recorded in the revolutionary period at Williamsburg, | + | In America, the choice of the obelisk for political commemoration in public spaces was recorded in the revolutionary period at Williamsburg, VA, where the monument was intended to honor those who opposed the Stamp Act. The repeal of that act was celebrated by the erection of a temporary obelisk in the [[Boston Common]], as illustrated in a print by [[Paul Revere]] [<span id="Fig_6_cite"></span>[[#Fig_6|See Fig. 6]]]. After the War of Independence, [[Pierre-Charles L’Enfant]] specified obelisks as decorations in the new capital city that would memorialize the heroes of the Revolution. His plan of 1792 indicated these monuments embellishing the public [[square]]s of the new capital [<span id="Fig_8_cite"></span>[[#Fig_8|See Fig. 8]]]. The association with republican Rome, the site of many obelisks, was a frequent iconographic reference in early federal decoration and rhetoric. The obelisk was a popular public and political monument, as <span id="Mills_cite"></span>[[Robert Mills]] argued, not only because of its association with antiquity and republicanism, but also because its surfaces allowed inscriptions that could particularize the memorial function. He described, for example, how the ornamentation on his design for the [[Bunker Hill Monument|Bunker Hill]] obelisk symbolized the states' formation of the federal union ([[#Mills|view text]]). |

[[File:0552.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 3, [[Charles Fraser]], ''Monument of Lieutenant Governor Bull'' (Ashley Hall), c. 1800.]] | [[File:0552.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 3, [[Charles Fraser]], ''Monument of Lieutenant Governor Bull'' (Ashley Hall), c. 1800.]] | ||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

[[Robert Mills]] pointed out that its diminishing width made the obelisk lighter and more graceful than another popular monument form, the [[column]]. <span id="Willard_cite"></span>[[Solomon Willard]] preferred the obelisk to the [[column]], the latter being too “splendid” ([[#Willard|view text]]). It was both the [[picturesque]] effect as well as the historical significance of the obelisk that motivated <span id="Loudon_cite"></span>[[J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon|J. C. Loudon’s]] recommendation of it in the garden ([[#Loudon|view text]]). | [[Robert Mills]] pointed out that its diminishing width made the obelisk lighter and more graceful than another popular monument form, the [[column]]. <span id="Willard_cite"></span>[[Solomon Willard]] preferred the obelisk to the [[column]], the latter being too “splendid” ([[#Willard|view text]]). It was both the [[picturesque]] effect as well as the historical significance of the obelisk that motivated <span id="Loudon_cite"></span>[[J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon|J. C. Loudon’s]] recommendation of it in the garden ([[#Loudon|view text]]). | ||

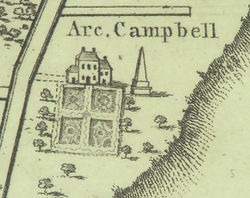

| − | The wave of monument building and civic improvement that marked the early Federal period carried with it an increasing number of obelisks. [[Belmont (Baltimore, | + | The wave of monument building and civic improvement that marked the early Federal period carried with it an increasing number of obelisks. [[Belmont (Baltimore, MD)|Belmont]], the Baltimore estate of [[Charles_François_Adrien_le_Paulmier,_le_Chevalier_d’Annemours|Charles François Adrien le Paulmier, le Chevalier d’Annemours]], featured an obelisk built in honor of Christopher Columbus [<span id="Fig_9_cite"></span>[[#Fig_9|See Fig. 9]]]; and [[Ashley Hall]] in Charleston, SC, displayed one in memory of Lt. Gov. William Bull [Fig. 3]. |

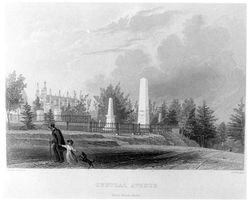

[[File:1170.jpg|thumb|Fig. 4, E. J. Pinkerton, ''General View of Laurel Hill Cemetery'', 1844.]] | [[File:1170.jpg|thumb|Fig. 4, E. J. Pinkerton, ''General View of Laurel Hill Cemetery'', 1844.]] | ||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

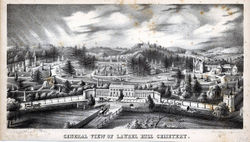

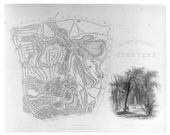

[[Thomas Jefferson|Jefferson]] and [[Charles Willson Peale|Peale]]’s garden obelisks served private but also commemorative purposes as both men planned to use the forms garden features that would eventually become their tombstones. In each case, these public figures mixed political and private associations in their choice of inscriptions. In addition to the political significance, the use of the Egyptian obelisk for funereal ornamentation was well established in America. The discussion surrounding the designs for [[Mount Auburn Cemetery]] in Cambridge, MA, conveyed the popular interest in Egyptian-style monuments and architecture in early rural [[cemetery|cemeteries]]. Defenders of the plans for the [[cemetery]] called it an “architecture of the dead” because nearly all surviving Egyptian architecture or monuments had a funerary purpose.<ref>Mount Auburn Cemetery was originally to be named the “American Père Lachaise.” Although the name was not given, Mount Auburn Cemetery was often compared with Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. Richard Etlin recounts the history of this French cemetery as an influential landscape continued in America. He discusses the Egyptian style of much of that cemetery’s architecture and monuments. See Richard A. Etlin, ''The Architecture of Death: The Transformation of the Cemetery in Eighteenth-Century Paris'' (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1984), 358–68, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/G6QIFAZT/q/etlin view on Zotero].</ref> The Egyptian practice of placing the tomb “in the midst of the beauty and luxuriance of nature”<ref>Blanche Linden-Ward, ''Silent City on a Hill: Landscapes of Memory and Boston’s Mount Auburn Cemetery'' (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1989), 261–66, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/K5AS42UI view on Zotero].</ref> was also cited as justification for this new garden type [Figs. 4 and 5]. | [[Thomas Jefferson|Jefferson]] and [[Charles Willson Peale|Peale]]’s garden obelisks served private but also commemorative purposes as both men planned to use the forms garden features that would eventually become their tombstones. In each case, these public figures mixed political and private associations in their choice of inscriptions. In addition to the political significance, the use of the Egyptian obelisk for funereal ornamentation was well established in America. The discussion surrounding the designs for [[Mount Auburn Cemetery]] in Cambridge, MA, conveyed the popular interest in Egyptian-style monuments and architecture in early rural [[cemetery|cemeteries]]. Defenders of the plans for the [[cemetery]] called it an “architecture of the dead” because nearly all surviving Egyptian architecture or monuments had a funerary purpose.<ref>Mount Auburn Cemetery was originally to be named the “American Père Lachaise.” Although the name was not given, Mount Auburn Cemetery was often compared with Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. Richard Etlin recounts the history of this French cemetery as an influential landscape continued in America. He discusses the Egyptian style of much of that cemetery’s architecture and monuments. See Richard A. Etlin, ''The Architecture of Death: The Transformation of the Cemetery in Eighteenth-Century Paris'' (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1984), 358–68, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/G6QIFAZT/q/etlin view on Zotero].</ref> The Egyptian practice of placing the tomb “in the midst of the beauty and luxuriance of nature”<ref>Blanche Linden-Ward, ''Silent City on a Hill: Landscapes of Memory and Boston’s Mount Auburn Cemetery'' (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1989), 261–66, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/K5AS42UI view on Zotero].</ref> was also cited as justification for this new garden type [Figs. 4 and 5]. | ||

| − | The obelisk had a long and continuous tradition in American landscape design that began in the colonies and lasted well into the nineteenth century. The feature was utilized in both [[public garden|public]] and private gardens ranging in scale from a few feet to the tallest edifices in American architecture until the advent of the skyscraper. Obelisks persisted over time despite changes in garden styles, finding a place within the Anglo-Dutch landscapes of Williamsburg, | + | The obelisk had a long and continuous tradition in American landscape design that began in the colonies and lasted well into the nineteenth century. The feature was utilized in both [[public garden|public]] and private gardens ranging in scale from a few feet to the tallest edifices in American architecture until the advent of the skyscraper. Obelisks persisted over time despite changes in garden styles, finding a place within the Anglo-Dutch landscapes of Williamsburg, VA, in the mid-eighteenth century, as well as in the [[picturesque]] landscapes of rural [[cemetery|cemeteries]] one hundred years later. |

--''Therese O'Malley'' | --''Therese O'Malley'' | ||

| Line 38: | Line 38: | ||

<div id="Fig_6"></div>[[File:0482.jpg|thumb|Fig. 6, [[Paul Revere]], ''A View of the Obelisk erected under Liberty-Tree in Boston on the Rejoicings for the Repeal of the Stamp Act'', 1766. [[#Fig_6_cite|Back up to history]]]] | <div id="Fig_6"></div>[[File:0482.jpg|thumb|Fig. 6, [[Paul Revere]], ''A View of the Obelisk erected under Liberty-Tree in Boston on the Rejoicings for the Repeal of the Stamp Act'', 1766. [[#Fig_6_cite|Back up to history]]]] | ||

| − | * Anonymous, December 11, 1766, describing in the ''Virginia Gazette'' a decision to erect an obelisk in Williamsburg, | + | * Anonymous, December 11, 1766, describing in the ''Virginia Gazette'' a decision to erect an obelisk in Williamsburg, VA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; hereafter CWF) |

:“Occassioned by a Resolution of the Honourable House of Burgesses in Virginia, to erect an '''Obelisk''' in Memory of those illustrious Patriots who distinguished themselves in Parliament, by their spirited Opposition to the Stamp-Act.” | :“Occassioned by a Resolution of the Honourable House of Burgesses in Virginia, to erect an '''Obelisk''' in Memory of those illustrious Patriots who distinguished themselves in Parliament, by their spirited Opposition to the Stamp-Act.” | ||

| Line 78: | Line 78: | ||

<div id="Fig_9"></div>[[File:1977_detail.jpg|thumb|Fig. 9, Charles Varlé (artist), Francis Shallus (engraver), ''Warner & Hanna’s Plan of the City and Environs of Baltimore'' [detail], 1801. [[#Fig_9_cite|Back up to history]]]] | <div id="Fig_9"></div>[[File:1977_detail.jpg|thumb|Fig. 9, Charles Varlé (artist), Francis Shallus (engraver), ''Warner & Hanna’s Plan of the City and Environs of Baltimore'' [detail], 1801. [[#Fig_9_cite|Back up to history]]]] | ||

| − | * Anonymous, August 17, 1792, describing in the ''Claypole’s Daily Advertiser (Philadelphia)'' [[Belmont (Baltimore, | + | * Anonymous, August 17, 1792, describing in the ''Claypole’s Daily Advertiser (Philadelphia)'' [[Belmont (Baltimore, MD)|Belmont]], country seat of [[Charles_François_Adrien_le_Paulmier,_le_Chevalier_d’Annemours|Charles François Adrien le Paulmier, le Chevalier d’Annemours]], Baltimore, MD (quoted in Thompson 1906: 246)<ref>Henry F. Thompson, "The Chevalier D’Annemours,” ''Maryland Historical Magazine'', 1 (1906): 241–46, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/ATM2VZQX view on Zotero].</ref> |

:“[The Chevalier d’Annemours built] an '''obelisk''' to honour the memory of that immortal man—Christopher Columbus . . . in a [[grove]] in one of the gardens of the villa . . . on the 3rd of August, 1792, the anniversary of the sailing of Columbus from Spain.” [Fig. 9] | :“[The Chevalier d’Annemours built] an '''obelisk''' to honour the memory of that immortal man—Christopher Columbus . . . in a [[grove]] in one of the gardens of the villa . . . on the 3rd of August, 1792, the anniversary of the sailing of Columbus from Spain.” [Fig. 9] | ||

| Line 156: | Line 156: | ||

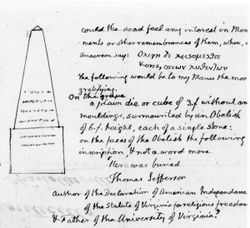

| − | * <div id="Jefferson"></div>[[Thomas Jefferson|Jefferson, Thomas]], pre-1826, description of his own tombstone planned for [[Monticello]], plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, | + | * <div id="Jefferson"></div>[[Thomas Jefferson|Jefferson, Thomas]], pre-1826, description of his own tombstone planned for [[Monticello]], plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, VA (Massachusetts Historical Society, Coolidge Collection: K162), [[#Jefferson_cite|back up to history]] |

:“On the grave a plain die or cube of 3 feet without any moldings, surmounted by an '''obelisk''' of 6 f. height, each of a single stone: on the face of the '''Obelisk''' the following inscription, and not a word more: Here was buried / Thomas Jefferson, / author of the Declaration of Independence / of the Statute of Virginia for religious freedom / & Father of the [[University of Virginia]] because by these, as testimonials that I have lived, I [w]ish most to be remembered. to be of the coarse stone of which my [[column|columns]] are made, that no one might be tempted hereafter to destroy it for the value of the materials. my bust by Ciracchi, with the pedestal and truncated [[column]] on which it stands, might be given to the University if they would place it in the Dome room of the Rotunda. on the Die of the '''obelisk''' might be engraved Born Apr. 2. 1763.O.S. / Died___" [Fig. 13] | :“On the grave a plain die or cube of 3 feet without any moldings, surmounted by an '''obelisk''' of 6 f. height, each of a single stone: on the face of the '''Obelisk''' the following inscription, and not a word more: Here was buried / Thomas Jefferson, / author of the Declaration of Independence / of the Statute of Virginia for religious freedom / & Father of the [[University of Virginia]] because by these, as testimonials that I have lived, I [w]ish most to be remembered. to be of the coarse stone of which my [[column|columns]] are made, that no one might be tempted hereafter to destroy it for the value of the materials. my bust by Ciracchi, with the pedestal and truncated [[column]] on which it stands, might be given to the University if they would place it in the Dome room of the Rotunda. on the Die of the '''obelisk''' might be engraved Born Apr. 2. 1763.O.S. / Died___" [Fig. 13] | ||

Revision as of 22:20, January 31, 2018

History

The term obelisk was used in the American colonies and early Republic to refer to a slender shaft or pillar with four faces that diminished in width from the base to a pyramidal top. Obelisks were generally made of wood, granite, marble, or, as Jefferson prescribed for his tombstone, “coarse stone” (view text). According to Batty Langley in New Principles of Gardening (1728), they could also be made of trellis work and covered with climbing plants to give the effect of a living obelisk (view text). Some obelisks were placed upon pedestals that were cube or temple forms; others rose directly from the ground.

In the designed landscape, the obelisk served two functions: as a garden ornament and as a monument with emblematic significance. Obelisks were important in the designed landscape or pleasure garden because they punctuated the vista or provided a place from which to gain a view. In order to serve these purposes, treatise authors recommended placing obelisks on elevated sites, although this treatment was not always used. Obelisks, which varied in size, were placed either in the center of open spaces or at the terminus of circulation routes. In both cases, they served as focal points. They often appeared in openings where radial sight lines were clear, as indicated by Hannah Callender in her 1762 description of Judge William Peters’s estate, Belmont, near Philadelphia, where she wrote that the avenue “looks to the obelisk” (view text).[1]

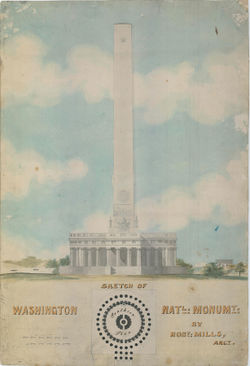

In nineteenth-century America, the obelisk was utilized on a monumental scale in public landscape design. Some examples were built as hollow shafts that could be ascended by means of an internal staircase leading to interior lookout platforms or external galleries, allowing the visitor a panoramic view of the surrounding landscape.[2] Solomon Willard’s Bunker Hill Monument in Boston was the earliest obelisk of this type, dating from 1825 [Fig. 1].[3] Monumental obelisks were also striking landmarks in the relatively low urban skylines of the first half of the nineteenth century. Robert Mills, architect of the Washington Monument in Washington, D.C., designed several monumental obelisks that served both as observation towers and civic displays [Fig. 2].[4]

The obelisk’s rich antique associations imbued it with symbolic significance. Its origins in Egypt, prominence in the Roman world, and, since the Renaissance, use in gardens and parks lent a vocabulary of the exotic and the historic to American landscape design. Several collected treatise citations recount the best-known examples of ancient obelisks, many of which have survived into the modern period. Excavations in Rome during the seventeenth century, for example, revealed dozens of Egyptian obelisks that were re-erected throughout the city. At the same time, modern obelisks ornamented French gardens such as Versailles. Many great gardens in Britain in the eighteenth century also featured obelisks: Castle Howard, Chiswick House, Holkham Hall, and Montacute House, to name a few.[5] With the French invasion of Egypt in 1798, the taste for Egyptian statuary and styles increased and obelisks appeared more frequently as props in gardens.[6] Thus the tradition of obelisks in European gardens and public spaces transmitted via literature, European designers, and American visitors abroad, was a significant influence on American garden practice. Both Ephraim Chambers (1741–43) and Noah Webster (1828) described the use of hieroglyphic inscriptions on obelisks that expressed the historic tradition from which the form derived.

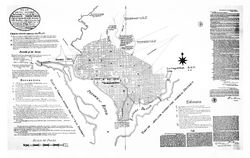

In America, the choice of the obelisk for political commemoration in public spaces was recorded in the revolutionary period at Williamsburg, VA, where the monument was intended to honor those who opposed the Stamp Act. The repeal of that act was celebrated by the erection of a temporary obelisk in the Boston Common, as illustrated in a print by Paul Revere [See Fig. 6]. After the War of Independence, Pierre-Charles L’Enfant specified obelisks as decorations in the new capital city that would memorialize the heroes of the Revolution. His plan of 1792 indicated these monuments embellishing the public squares of the new capital [See Fig. 8]. The association with republican Rome, the site of many obelisks, was a frequent iconographic reference in early federal decoration and rhetoric. The obelisk was a popular public and political monument, as Robert Mills argued, not only because of its association with antiquity and republicanism, but also because its surfaces allowed inscriptions that could particularize the memorial function. He described, for example, how the ornamentation on his design for the Bunker Hill obelisk symbolized the states' formation of the federal union (view text).

The Egyptian obelisk was appropriate for the expression of early national symbolism because of the equation of the newly formed United States with another “first civilization.” Freemasonry also fostered the link with ancient Egypt. The obelisk exemplified “cubic architecture” preferred by the Burlington circle of Freemason architects, derived from Palladio and James Gibbs and practiced in America by Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Henry Latrobe. It was seen as a repudiation of baroque eclecticism, as well as colonial red-brick Anglo-Dutch architecture. For American Freemasons, building took on a political cast that extended into the garden.[7]

Robert Mills pointed out that its diminishing width made the obelisk lighter and more graceful than another popular monument form, the column. Solomon Willard preferred the obelisk to the column, the latter being too “splendid” (view text). It was both the picturesque effect as well as the historical significance of the obelisk that motivated J. C. Loudon’s recommendation of it in the garden (view text).

The wave of monument building and civic improvement that marked the early Federal period carried with it an increasing number of obelisks. Belmont, the Baltimore estate of Charles François Adrien le Paulmier, le Chevalier d’Annemours, featured an obelisk built in honor of Christopher Columbus [See Fig. 9]; and Ashley Hall in Charleston, SC, displayed one in memory of Lt. Gov. William Bull [Fig. 3].

The visual and textual evidence surrounding Charles Willson Peale’s obelisk represents a clear correlation between usage, treatise citation, and image based on early American primary sources. Peale noted his reliance on G. Gregory’s definition in the Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (1806–7, 1816) in building an obelisk in his garden at Belfield. Gregory’s description gave the proportions and dimensions of the “truncated, quadrangular, and slender pyramid” that Peale sketched in his letters and inscribed on an obelisk [See Fig. 10]. The emblematic significance of this obelisk was also suggested in Gregory’s treatise description of the obelisk built to memorialize Ptolemy Philadelphus, the ancient Egyptian who built the great obelisk lighthouse and library at Alexandria, and after whom Peale of Philadelphia may have been modeling himself (view text).

Jefferson and Peale’s garden obelisks served private but also commemorative purposes as both men planned to use the forms garden features that would eventually become their tombstones. In each case, these public figures mixed political and private associations in their choice of inscriptions. In addition to the political significance, the use of the Egyptian obelisk for funereal ornamentation was well established in America. The discussion surrounding the designs for Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, MA, conveyed the popular interest in Egyptian-style monuments and architecture in early rural cemeteries. Defenders of the plans for the cemetery called it an “architecture of the dead” because nearly all surviving Egyptian architecture or monuments had a funerary purpose.[8] The Egyptian practice of placing the tomb “in the midst of the beauty and luxuriance of nature”[9] was also cited as justification for this new garden type [Figs. 4 and 5].

The obelisk had a long and continuous tradition in American landscape design that began in the colonies and lasted well into the nineteenth century. The feature was utilized in both public and private gardens ranging in scale from a few feet to the tallest edifices in American architecture until the advent of the skyscraper. Obelisks persisted over time despite changes in garden styles, finding a place within the Anglo-Dutch landscapes of Williamsburg, VA, in the mid-eighteenth century, as well as in the picturesque landscapes of rural cemeteries one hundred years later.

--Therese O'Malley

Texts

Usage

- Callender, Hannah, June 30, 1762, diary entry describing Belmont, estate of William Peters, near Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Callender 2010: 183) [10] back up to history

- “ . . . a broad walk of english Cherre trys leads down to the river, the doors of the hous opening opposite admitt a prospect [of] the length of the garden thro' a broad gravel walk, to a large hansome summer house in a grean, from these Windows down a Wisto terminated by an Obelisk, on the right you enter a Labarynth of hedge and low ceder with spruce, in the middle stands a Statue of Apollo, note: in the garden are the Statues of Dianna, Fame & Mercury, with urns. we left the garden for a wood cut into Visto’s, in the midst a chinese temple, for a summer house, one avenue gives a fine prospect of the City, with a Spy glass you discern the houses distinct, Hospital, & another looks to the Oblisk.”

- Anonymous, December 11, 1766, describing in the Virginia Gazette a decision to erect an obelisk in Williamsburg, VA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; hereafter CWF)

- “Occassioned by a Resolution of the Honourable House of Burgesses in Virginia, to erect an Obelisk in Memory of those illustrious Patriots who distinguished themselves in Parliament, by their spirited Opposition to the Stamp-Act.”

- Anonymous, May 19, 1776, describing in the Boston Gazette Boston Common, Boston, MA (quoted in Brigham 1954: 21) [11]

- “[to] be exhibited on the Common, an Obelisk—A Description of which is engraved by Mr. Paul Revere; and is now selling by Edes & Gill.” [Fig. 6]

- Anonymous, May 22, 1776, describing in the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston News-Letter Boston Common, Boston, MA (quoted in Brigham 1954: 22) [11]

- “At Eleven o'clock the Signal being given by a Discharge of 21 Rockets, the horizontal Wheel on the Top of the Pyramid or Obelisk was play’d off, ending in the Discharge of sixteen Dozen of Serpents in the Air, which concluded the Shew.”

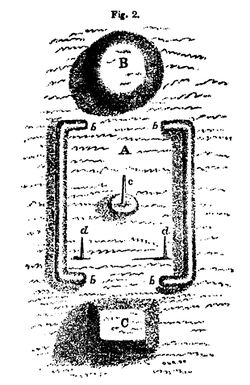

- Bartram, William, 1789, describing settlements of the Muscogulge and Cherokee Indians (1853: 51-53) [12]

- “PLAN OF THE ANCIENT CHUNKY-YARD.

- “The subjoined plan . . . will illustrate the form and character of these yards. [Fig. 7]

- “A, the great area, surrounded by terraces or banks.

- “B, a circular eminence, at one end of the yard, commonly nine or ten feet higher than the ground round about. Upon this mound stands the great Rotunda, Hot House, or Winter Council House, of the present Creeks. It was probably designed and used by the ancients who constructed it, for the same purpose.

- “C, a square terrace or eminence, about the same height with the circular one just described, occupying a position at the other end of the yard. Upon this stands the Public Square.

- “The banks inclosing the yard are indicated by the letters b, b, b, b; c indicate the "Chunk-Pole", and d, d, the "Slave-Posts.”

- “Sometimes the square, instead of being open at the ends, as shown in the plan, is closed upon all sides by the banks. In the lately built, or new Creek towns, they do not raise a mound for the foundation of their Rotundas or Public Squares. The yard, however, is retained, and the public buildings occupy nearly the same position in respect to it. They also retain the central obelisk and the slave-posts.”

- L’Enfant, Pierre-Charles, January 4, 1792, from notes on "Plan of the City,” describing Washington, D.C. (quoted in Caemmerer 1950: 165)[13]

- “The Center of each Square will admit of Statues, Columns, Obelisks, or any other ornament such as the different States may choose to erect: to perpetuate not only the memory of such individuals whose Counsels, or military achievements were conspicuous in giving liberty and independence to this Country; but also those whose usefulness hath rendered them worthy of general imitation: to invite the youth of succeeding generations to tread in the paths of those Sages, or heroes whom their Country has thought proper to celebrate.” [Fig. 8]

- Anonymous, August 17, 1792, describing in the Claypole’s Daily Advertiser (Philadelphia) Belmont, country seat of Charles François Adrien le Paulmier, le Chevalier d’Annemours, Baltimore, MD (quoted in Thompson 1906: 246)[14]

- “[The Chevalier d’Annemours built] an obelisk to honour the memory of that immortal man—Christopher Columbus . . . in a grove in one of the gardens of the villa . . . on the 3rd of August, 1792, the anniversary of the sailing of Columbus from Spain.” [Fig. 9]

- Dwight, Timothy, 1796, describing New Haven Burying Ground, New Haven, CT (1821: 1:192) [15]

- “The monuments in this ground are almost universally of marble; in a few instances from Italy; in the rest, found in this and neighbouring States. A considerable number are obelisks; others are tables; and others, slabs, placed at the head and foot of the grave. The obelisks are placed, universally, on the middle line of the lots; and thus stand in a line, successively, through the parallelograms.”

- Moore, Thomas, 1804, describing Washington, D.C. (quoted in Reps 1965: 257) [16]

- Anonymous, July 2, 1804, describing Vauxhall Gardens, New York, N.Y. (New York Daily Advertiser)

- “At 8 o'clock will commence the most complete illumination, consisting of upwards of four thousand Colored Lamps, and decorated . . . with Pyramids, Obelisks, Arches, &c.”

- Peale, Charles Willson, November 12, 1813, in a letter to his daughter, Angelica Peale Robinson, describing Belfield, estate of Charles Willson Peale, Germantown, PA (Miller, Hart, and Ward, eds., 1991: 3:216)[17]

- “I have made an Oblisk to terminate a Walk in the Garden, read in Dictionary of Arts for description of them. I made it of rough boards & white washed it with lime & allum — The allum It is said will convert the lime in time to Stone. I have put the following motto on it — on one side 'Never return an Injury, It is a noble Triumph to overcome Evil by Good.' another, 'Labour while you are able it will give health to the Body — peaceful content to the mind.' another, 'He that will live in peace & Rest, must hear, and see, and say the best & in french 'y voy, & te tas, si tu veux vivre en paix.' and on another 'Neglect no Duty.' The distick which I have adopted is claimed by several Nations, I have put the french because it is more concise & equally expressive.” [Fig. 10]

- Peale, Charles Willson, November 22, 1815, in a letter to his daughter, Angelica Peale Robinson, describing Belfield, estate of Charles Willson Peale, Germantown, PA (Miller, Hart, and Ward, eds., 1991: 3:370-371) [17]

- “The objects in sight are the road ascending to the Dwelling, Stone wall & Thorn hedge on it inclosing the Garden. The Garden Gate at the Fountain, Green House, Summer house a doom supported by 6 Pillars and bust of Washington crowning it — beyond that an Oblisk The Hay barracks; Barn with the wind mill on top of it to [pu] pump water for the Stock; Stables; Mantion-House Wash house and connecting Piaza; Carriage House; Spring House; Bath house and Cover of the Ice-House. The whole comprehending a tolerable handsome View including Trees of various foliages . . . ” [Fig. 11]

- Peale, Charles Willson, October 1, 1818, in a letter to his son, Rembrandt Peale (Miller, Hart, and Ward, eds., 1991: 3:607) [17]

- “I have chosen two views I wish to paint, one is at the beginning of the rise of the high hill leading to Germantown, it takes in my Oblisk, Barn and Mansion House and both the Summer Houses — The Gate & willow tree on the left, the hill back of the Garden, the road, the water in the road & mill race, and a piece of Mr. Wistar’s wood for a finish on the right of the picture.” [Fig. 12]

- Peale, Charles Willson, January 14, 1824, in a letter to his son, Charles Linnaeus Peale, describing Belfield, estate of Charles Willson Peale, Germantown, PA (quoted in Rudnytzky 1986: 32) [18]

- “Dear Linnius I wish you to consider whether it is not better to avoid these expenses by burying your Child in the Garden on the south side of the Oblisk, a place which if I hold the farm untill my decease, I shall desire to have my body deposited. This has been my determination ever since I painted those inscriptions.”

- Mills, Robert, March 20, 1825, in a letter to the Monument Commission, describing plans for the Bunker Hill Monument, Boston, MA (quoted in Gallagher 1935: 204–6), [19] back up to history

- “I have the honor to submit for your consideration and approval, a design for the Monument you propose erecting on the spot, where the Brave General Warren and his worthy associates fell; to commemorate their valor, and the gratitude of their Country. . . .

- “In the design for the Monument which I now have the honor to lay before you, I would recommend the adoption of the obelisk form, in preference to the Column — the detail I have affixed to this species of pillar, will be found to give it a peculiarly interesting character, embracing originality of effect with simplicity of design, economy in execution, great solidity and capacity for decoration, reaching to the highest degree of splendor consistant with good taste. . . .

- “The obelisk form is, for monuments, of greater antiquity than the Column as appears from history, being used as early as the days of Ramises King of Egypt in the time of the Trojan War—Kercher reckons up 14 obelisk that were celebrated above the rest, namely, that of Alexandria; that of the Barberins; those of Constantinople; of the Mons Esquilinus; of the Campus Flaminius; of Florence; of Heliopolis; of Ludorisco; of St. Makut, of the Medici of the vatican; of M. Coelius, and that of Pamphila. The highest on record mentioned, is that erected by Ptolemy Philadelphus in memory of Arsinoe.

- “The obelisk form is peculiarly adapted to commemorate great transactions from its lofty character, great strength, and furnishing a fine surface for inscriptions—There is a degree of lightness and beauty in it that affords a finer relief to the eye than can be obtained in the regular proportioned Column.

- “Our monument includes a square of 24 feet at the base above the zocle or plinth, and is 15 feet square at the top — Its total elevation is 220 feet above the pavement — The shaft is divided into four great compartments for inscriptive, and other decorations, which come more immediately under the eye by means of oversailing platforms, enclosed by balastrades, supported as it were by winged globes (symbols of immortality peculiarly of a monumental Character).

- “A series of shields bandround the foot of the shaft, representing the 13 States, which form’d the Federal union, as principal, having their arms sculptured on their face — A star, on a plain tablet in connection with the former, represents each the other states which now constitute our Union — the whole surmounted by spears and wreathes.

- “A flight of stone steps, or a rising platform, surround the base, from whence the lower inscriptions are read —

- “This is inclosed by a rich bronzed palisade — The entrance into the monument is from this platform, when a flight of stone steps, winding round a pillar, ascends to the top, and communicates with the several platforms. Between the galleries, on each face of the pillar, a wreath, hung on a speer, encircles the letter W, which is otherwise decorated and constitute apertures for lighting the interior of the Monument — over the Last wreath, and near the apex of the obelisk, a great star is placed, emblematic of the glory to which the name of Warren has risen — A tripod crowns the whole and forms the surmounting of the Monument — This tripod is the classic emblem of immortality.”

- Willard, Solomon, 1825, describing the Bunker Hill Monument, Boston, MA (quoted in Zukowsky 1976: 579), [2] back up to history

- “The obelisk I have always preferred for its severe cast and its nearer approach to the simplicity of nature than the others. The column might be more splendid. The character of the obelisk, without a pedestal, seems to be strictly appropriate for the occasion and I think would rank first as a specimen of art and be highly creditable to the taste of the age.”

- Anonymous, October 9, 1825, describing in the St. Philip’s Parish Vestry Book meeting resolutions made in Charleston, SC (CWF)

- “The Committee on Monuments has proposed . . . Sixth Class. This embraces Obelisks, Pyramids, Urns & every Species of Columnar Pedestal.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, pre-1826, description of his own tombstone planned for Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, VA (Massachusetts Historical Society, Coolidge Collection: K162), back up to history

- “On the grave a plain die or cube of 3 feet without any moldings, surmounted by an obelisk of 6 f. height, each of a single stone: on the face of the Obelisk the following inscription, and not a word more: Here was buried / Thomas Jefferson, / author of the Declaration of Independence / of the Statute of Virginia for religious freedom / & Father of the University of Virginia because by these, as testimonials that I have lived, I [w]ish most to be remembered. to be of the coarse stone of which my columns are made, that no one might be tempted hereafter to destroy it for the value of the materials. my bust by Ciracchi, with the pedestal and truncated column on which it stands, might be given to the University if they would place it in the Dome room of the Rotunda. on the Die of the obelisk might be engraved Born Apr. 2. 1763.O.S. / Died___" [Fig. 13]

- Dearborn, H.A.S., 1832, describing Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, MA (quoted in Harris 1832: 68) [20]

- “Among the hills, glades, and dales, which are now covered with evergreen and deciduous trees and shrubs, may be selected sites for isolated graves, and tombs, and these, being surmounted with columns, obelisks, and other appropriate monuments of granite and marble, may be rendered interesting specimens of art; they will also vary and embelish the scenery embraced within the scope of the numerous sinuous avenues, which may be felicitously opened in all directions and to a vast extent, from the diversified and picturesque features which the topography of the tract of land presents.”

- Mills, Robert, July 1, 1832, in a letter to Richard Walleck, describing Charlestown, MA (quoted in Gallagher 1935: 102) [19]

- “When the Bunker Hill Monument Committee advertised for designs for the Monument, I took a good deal of pains to study one which should do honor to the memory of those worthies it was intended to commemorate, and prove an ornament to the city it was to overlook. I went into some detail on the subject of monuments generally and in sending them two designs, recommended in strong terms the adoption of the Obelisk design, not only from its combining simplicity and economy with grandeur, but as there was already a column of massy proportions erected in Baltimore, we ought not, therefore, to repeat this figure, but construct one of equally imposing figure.”

- Anonymous, 1839, describing Mount Auburn Cemtery, Cambridge, MA (p. 47-48) [21]

- “That part of the land which has been recommended for a CEMETERY, may be circumvallated by a spacious avenue, bordered by trees, shrubbery and perennial flowers, — rather as a line of demarcation, than of disconnexion, — for the ornamental grounds of the GARDEN should be apparently blended with those of the Cemetery, and the walks of each so intercommunicate, as to afford an uninterrupted range over both, as one common domain.

- “Among the hills, glades and dales, which are now covered with evergreen, and deciduous trees and shrubs, may be selected sites for isolated graves, and tombs, and these being surmounted with columns, obelisks, and other appropriate monuments of granite and marble, may be rendered interesting specimens of art; they will also vary and embellish the scenery, embraced within the scope of the numerous sinuous avenues that may be felicitously opened, in all directions, and to a vast extent, from the diversifies and picturesque features which the topography of this tract of land presents.” [Fig. 14]

- Cleaveland, Nehemiah, 1847, describing Greenwood Cemetery, Brooklyn, N.Y. (p. 73) [22]

- “We have in this view an obelisk of considerable height, and in some respects, peculiar. The shaft is surrounded by several narrow fillets slightly raised, and connected with other ornaments. Just above the base, on the front side, is a female bust in high relief. A tablet below records the name, virtues, and premature decease of a young wife and mother. The material is brown stone, and the work is finely executed.” [Fig. 15]

- Walter, Cornelia W., 1847, describing Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, MA (p. 23) [23]

- “The principle obelisk represented in the opposite engraving, is a lofty cenotaph of pure white marble, ornamented on the four sides with festoons of roses in relievo, and presenting altogether a monument of good proportion, strikingly chaste and simple.” [Fig. 16]

Citations

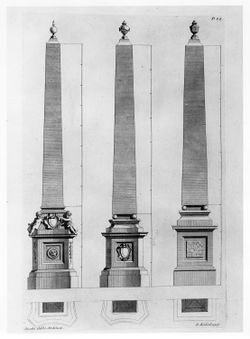

- Gibbs, James, 1728, A Book of Architecture (description of pl. 86)[24]

- “Three Draughts of Obelisques, more ornamental than the former: They keep the same Proportion with them; only that upon the left hand has four times the thickness of the Obelisque at bottom to the height of its Pedestal, because of the Ornaments upon it the top part may be made in the manner here drawn, or with other Ornaments at discretion. The Antients [sic] never placed their Obelisques upon moulded Bases; but Dominico Fontana and others have placed them upon Bases, which, in my opinion, is a great addition to their beauty, however that may be done or not at pleasure.” [Fig. 16]

- Langley, Batty, 1728, New Principles of Gardening (pp. 195–200),[25] back up to history

- “General DIRECTIONS, &c. . . .

- “XVIII. That the Intersections of Walks be adorn’d with Statues, large open Plains, Groves, Cones of Fruit, of Ever-Greens, of Flowering Shrubs, of Forest Trees, Basons, Fountains, Sun-Dials, and Obelisks. . . .

- “XXII. Obelisks of Trellip-Work [sic] cover’d with Passion-Flowers, Grapes, Honey-Suckles, obelisk and White Jessemine, are beautiful Ornaments in the Center of an open Plain, Flower-Garden, &c.”

- Chambers, Ephraim, 1741–43, Cyclopaedia (2:n.p.)[26]

- “OBELISK*, OBELISCUS, a quadrangular pyramid, very slender, and high; raised as an ornament, in some public place, or to shew some stone of enormous size; and frequently charged with inscriptions, and hieroglyphics. See MONUMENT.

- “* Borel derives the word from the Greek . . . a spit, broach, spindler, or even a kind of long javelin.—Pliny says, the Egyptians cut their obelisks in form of sun-beams; and that in the Phoenician language, the word obelisk signifies ray. . . .

- “The difference between obelisks and pyramids, according to some, consists in this, that the latter have large bases, and the former very small ones.

- “Though Cardan makes the difference to consist in this, that obelisks are to be all of a piece, or to consist of a single stone, and pyramids of several. See PYRAMID.

- “The proportions of the heighth and thickness are nearly the same in all obelisks; that is, their heighth is nine, or nine and a half, sometimes ten times their thickness; and their thickness or diameter a-top is never less than half, nor greater than three fourths of that at bottom.

- “This kind of monument appears very antient; and we are told was first made use of to transmit to posterity the principle precepts of philosophy, which were engraven in hieroglyphical characters hereon. — In after times they were used to immortalize the actions of heroes, and the memory of persons beloved.

- “The first obelisk we know of, was that raised by Ramses, king of Egypt, in the time of the Trojan war. It was 40 cubits high, and, according to Herodotus, employed 20000 men in the building. Phius, another king of Egypt, raised one of 45 cubits; and Ptolemy Philadelphus another of 88 cubits, in memory of Arsinoe. Vid. Porphyry.

- “Augustus erected an obelisk at Rome in the Campus Martius, which served to mark the hours on a horizontal dial drawn on the pavement. See DIAL.

- “F. Kircher reckons up 14 obelisks celebrated above the rest.”

- Halfpenny, William and John, 1755, Rural Architecture in the Chinese Taste ([1755] 1968: 7)[27]

- “The Elevation of an Obelisk 40 Feet high, proper to be situated at the Termination of a long Walk, or in the Center of a large Square, etc.” [Fig. 18]

- Johnson, Samuel, 1755, A Dictionary of the English Language (2:n.p.) [28]

- “Obelisk. n.s. [obeliscus, Latin.]

- “1. A magnificent high piece of solid marble, or other fine stone, having usually four faces, and lessening upwards by degrees, till it ends in a point like a pyramid.”

- M'Mahon, Bernard, 1806, The American Gardener’s Calendar (p. 64) [29]

- “In some spacious pleasure-grounds various light ornamental buildings and erections are introduced, as ornaments to particular departments; such as temples, bowers, banquetting houses, alcoves, grottos, rural seats, cottages, fountains, obelisks, statues, and other edifices; these and the like are usually erected in the different parts, in openings between the divisions of the ground, and contiguous to the terminations of grand walks, &c.”

- Gregory, G., 1816, A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (2:n.p.), [30] back up to history

- “OBELISK, a truncated, quadrangular, and slender pyramid raised as an ornament, and frequently charged either with inscriptions or hieroglyphics.

- “Obelisks appear to be of very great antiquity, and to be first raised to transmit to posterity precepts of philosophy, which were cut in hieroglyphical characters: afterwards they were used to immortalize the great actions of heroes, and the memory of persons beloved. . . .

- “The proportions in the height and thickness are nearly the same in all obelisks; their height being nine or nine and a half, and sometimes ten times, their thickness; and their diameter at the top never less than half; and never greater than three-fourths of that at the bottom. . . .

- “WILDERNESS. . . .

- “As to the walks, those that have the appearance of meanders, where the eye cannot discover more than twenty or thirty yards in length, are generally preferable to all others, and these should now and then lead into an open circular piece of grass; in the centre of which may be placed either an obelisk, statue, or fountain.”

- Loudon, J. C., 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (p. 361), [31] back up to history

- “1842. Monumental objects, as obelisks, columns, pyramids, may occasionally be introduced with grand effect, both in a picturesque and historical view, of which Blenheim, Stow, Castle Howard, &c., afford fine examples; but their introduction is easily carried to the extreme, and then it defeats itself, as at Stow.”

- Parmentier, André, 1828, The New American Gardener (quoted in Fessenden 1828: 187) [32]

- “Obelisks, columns, &c. should be placed on elevated places.”

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (2:n.p.) [33]

- “OB'ELISK, n. [L. obeliscus; Gr. . . .]

- “1. A truncated, quadrangular and slender pyramid intended as an ornament, and often charged with inscriptions or hieroglyphics. Some ancient obelisks appear to have been erected in honor of distinguished persons or their achievements. Ptolemy Philadelphus raised one of 88 cubits high in honor of Arsinee. Augustus erected one in the Campus Martius at Rome, which served to mark the hours on a horizontal dial drawn on the pavement. Encyc.”

- Tuthill, Louisa C., 1848, History of Architecture ([1848] 1988: 399) [34]

- “Obelisk. A monolithic pillar of a rectangular form, diminishing from the base to the top.”

Images

Inscribed

Thomas Jefferson, Letter describing an obelisk for his grave marker at Monticello [detail], n.d.

James Gibbs, "Three Draughts of Obelisques,” in A Book of Architecture (1728), pl. 86.

Paul Revere, A View of the Obelisk erected under Liberty-Tree in Boston on the Rejoicings for the Repeal of the Stamp Act, 1766.

Charles Willson Peale, Letter to Angelica Peale describing his garden at Belfield, November 12, 1813.

Charles Willson Peale, Letter to Angelica Peale describing his garden at Belfield, November 22, 1815.

Robert Mills, Details of the Washington Monument for Mr. Daugherty, Superintendent of the Work, Washington, D.C., October 24, 1848.

Facsimile reproduction of Pierre-Charles L’Enfant’s Plan of the City intended for the Permanent Seat of the Government of the United States . . . , 1791, made in 1887 by the Coast and Geodetic Survey. "The Center of each Square will admit of Statues, Columns, Obelisks . . . ”

t’l

Associated

Lewis Miller, “Bunker Hill Monument, Boston,” in Sketches and Chronicles (1966), p. 147.

William Bartram, “Plan of the Ancient Chunky-Yard,” in “Observations on the Creek and Cherokee Indians” (1789), from Transactions of the American Ethnological Society (1853), vol. 3, part 1, p. 52, fig. 2.

Robert Mills, Sketch of the Washington Nat’l. Monumt., 1845.

Attributed

Lewis Miller, “The Prospect Hill Cemetery” [detail], n.d., in Sketches and Chronicles (1966), p. 109.

Charles Fraser, Monument of Lieutenant Governor Bull (Ashley Hall), c. 1800.

Charles Fraser, Ashley Hall, 1803.

Mary Eliza Cushman, Memorial to Lt. Jacob Cushman, c. 1815–20.

Notes

- ↑ George Vaux, “Extracts from the Diary of Hannah Callender,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 12, no. 4 (January 1889): 455, view on Zotero

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 John Zukowsky, “Monumental American Obelisks: Centennial Vistas,” Art Bulletin 58, no. 4 (December 1976): 574–81, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Zukowsky argues that the American monumental obelisk was a combination of the solid obelisk and the hollow memorial column. As it developed through the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the monumental obelisk was a formally unique and distinctly American monument type that had military connotations and served as an image of continental expansion and unity during the centennial era. See Zukowsky 1976, 581.

- ↑ Mills designed four monumental obelisks during his career; see Pamela Scott, “Robert Mills and American Monuments” in Robert Mills, Architect, ed. John M. Bryan (Washington, D.C.: American Institute of Architects Press, 1989), 143-77, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe, Susan Jellicoe, Patrick Goode, and Michael Lancaster, eds., The Oxford Companion to Gardens (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), 408, view on Zotero.

- ↑ For information on the Egyptian style in America, see Richard G. Carrott, The Egyptian Revival: Its Sources, Monuments, and Meaning, 1808-1858 (Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press, 1978), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Roger Kennedy, Orders from France (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1990), 431, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Mount Auburn Cemetery was originally to be named the “American Père Lachaise.” Although the name was not given, Mount Auburn Cemetery was often compared with Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. Richard Etlin recounts the history of this French cemetery as an influential landscape continued in America. He discusses the Egyptian style of much of that cemetery’s architecture and monuments. See Richard A. Etlin, The Architecture of Death: The Transformation of the Cemetery in Eighteenth-Century Paris (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1984), 358–68, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Blanche Linden-Ward, Silent City on a Hill: Landscapes of Memory and Boston’s Mount Auburn Cemetery (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1989), 261–66, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Hannah Callender Sansom, The Diary of Hannah Callender Sansom: Sense and Sensibility in the Age of the American Revolution, ed. by Susan E. Klepp and Karin Wulf (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2010), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Clarence Brigham, Paul Revere’s Engravings (Worcester, MA: American Antiquarian Society, 1954), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Bartram, "Observations on the Creek and Cherokee Indians, 1789, with Prefatory and Supplementary Notes by E.G. Squier,” Transactions of the American Ethnological Society 3 (1853): 1–81, view on Zotero.

- ↑ H. Paul Caemmerer, The Life of Pierre-Charles L’Enfant, Planner of the City Beautiful, The City of Washington (Washington, D.C.: National Republic Publishing Company, 1950), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Henry F. Thompson, "The Chevalier D’Annemours,” Maryland Historical Magazine, 1 (1906): 241–46, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Timothy Dwight, Travels; in New-England and New-York, 4 vols. (New Haven: The Author, 1821), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John W. Reps, The Making of Urban America: A History of City Planning in the United States (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1965), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Lillian B. Miller, and et al., eds., The Selected Papers of Charles Willson Peale and His Family: The Belfield Farm Years, 1810-1820, vol. 3 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1983–2000), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Kateryna A. Rudnytzky, "The Union of Landscape and Art: Peale’s Garden at Belfield" (unpublished Honors thesis, LaSalle University, 1986), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 H. M. Pierce Gallagher, Robert Mills, Architect of the Washington Monument, 1781-1855 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1935), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thaddeus William Harris, A Discourse Delivered before the Massachusetts Horticultural Society on the Celebration of Its Fourth Anniversary, October 3, 1832 (Cambridge, MA: E. W. Metcalf, 1832), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, The Picturesque Pocket Companion and Visitor’s Guide through Mount Auburn (Boston: Otis, Broader, 1839), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Nehemiah Cleaveland, Green-Wood Illustrated: In Highly Finished Line Engraving, from Drawings Taken on the Spot (New York: R. Martin, 1847), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Cornelia Walter, Mount Auburn Illustrated. In highly finished line engraving, from drawings taken on the spot (New York: Martin and Johnson, [1847] 1850), view on Zotero.

- ↑ James Gibbs, A Book of Architecture, Containing Designs of Buildings and Ornaments (London: Printed for W. Innys et al, 1728), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Batty Langley, New Principles of Gardening, or The Laying Out and Planting Parterres, Groves, Wildernesses, Labyrinths, Avenues, Parks, &c (Originally published London: A. Bettesworth and J. Batley, etc., [1728] 1982), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Ephraim Chambers, Cyclopaedia, or An Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences . . . , 5th ed., 2 vols. (London: D. Midwinter et al., 1741-43), vol. 2, view on Zotero.

- ↑ William and John Halfpenny, Rural Architecture in the Chinese Taste (Bronx, N.Y. and London: Benjamin Blom, [1755] 1968), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language: In Which the Words Are Deduced from the Originals and Illustrated in the Different Significations by Examples from the Best Writers, 2 vols. (London: W. Strahan for J. and P. Knapton, 1755), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bernard M’Mahon, The American Gardener’s Calendar: Adapted to the Climates and Seasons of the United States. Containing a Complete Account of All the Work Necessary to Be Done . . . for Every Month of the Year . . . . (Philadelphia: Printed by B. Graves for the author, 1806), view on Zotero.

- ↑ G. Gregory, A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences, 3 vols. (Philadelphia: Isaac Peirce, 1816), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, 4th ed. (London: Longman et al, 1826), view on Zotero.

- ↑ André Parmentier, "The Art of Landscape Gardening,” in The New American Gardener, ed. Thomas Fessenden (Boston: J. B. Russell, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, vol. 2 (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Louisa C. Tuthill, History of Architecture, from the Earliest Times; Its Present Condition in Europe and the United States; with a Biography of Eminent Architects, and a Glossary of Architectural Terms, by Mrs. L. C. Tuthill (Philadelphia: Lindsay and Blakiston, [1848] 1988), view on Zotero.