Charles François Adrien le Paulmier, le Chevalier d’Annemours

Overview

Charles François Adrien le Paulmier, le Chevalier d’Annemours (1742–March 1, 1809) served as French Consul General at Baltimore from 1779 to 1793. He developed formal gardens at his homes in Baltimore and Louisiana.

History

After leaving his native Normandy for Martinique at the age of twelve, the Chevalier d’Annemours divided his time between France, England, the West Indies, and America. He established a number of business ventures in Philadelphia and made influential connections.[1] Between 1773 and 1776, while resident in France, he wrote four memoirs on the subject of the American colonies.[2] Returning to America in 1777, he represented France in various official capacities, including Consul General at Baltimore for the five southern states of Maryland, Virginia, Georgia, and North and South Carolina.[3] An amateur student of natural history, d’Annemours was elected a foreign member of the American Philosophical Society in 1783, and he received a visit from his compatriot, the French botanist André Michaux (1746–1802), on August 24, 1789.[4]

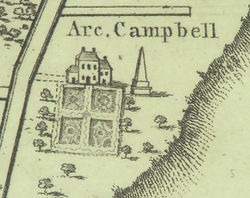

Around 1782 d’Annemours built a two-story house at Belmont, a 50-acre estate on “one of the most commanding sites in the suburbs of the city, overlooking a large part of the town, the Patapsco river, etc.”[5] The appearance of the house, now demolished, was documented in 1936 by photographs made by the Historic American Building Survey.[6] D’Annemours regarded the United States as his adopted country. When the French consulate at Baltimore closed in January 1793, he decided to remain in America rather than return to France, retiring to Belmont with the intention of devoting himself to the study of the arts and sciences.[7] The previous year d’Annemours had erected at Belmont a monument in honor of Christopher Columbus.[8] Dedicated on October 12, 1792, the 300th anniversary of Columbus’s arrival in the New World, the monument took the form of a 44-and-a-half-foot high obelisk fashioned of brick covered with stucco, bearing the inscription “Sacred/to the/Memory/of/Chris. Columbus/Octob. XII/MDCC VIIIC.” The obelisk originally stood on an artificial mound in a grove of cedar and ash trees about 100 yards from D’Annemours’s house.[9] It appears in Charles Varlé’s Warner & Hanna’s Plan of the City and Environs of Baltimore, drawn in 1797, a year after d’Annemours sold Belmont to Archibald Campbell [Fig. 1].

Having agreed to assist the Spanish government in recruiting settlers to colonize the wilderness that lay along the Ouachita River in Louisiana, d’Annemours journeyed there in July 1796, bringing with him six slaves and two English workmen, as well as an extensive library and a collection of scientific instruments.[10] Now describing himself as a cultivateur (farmer), d’Annemours purchased from Joseph de la Baume a plantation on the Ouachita River, where he built “a very pretty house,” experimented with growing wheat, and employed his slaves to lay out a formal garden.[11] The French writer Charles César Robin, who toured the property in 1804, charged d’Annemours with “disfiguring a spacious field with a tiny garden of coldly spaced groups of plants,” but acknowledged that he “delighted in strolling along an avenue of sycamores neatly aligned” by d’Annemours, which allowed him to imagine he was back in Paris (view text).[12] In a memoir written in 1803 d’Annemours provided a detailed account of the geography of Louisiana (particularly the Ouachita District) with a view to promoting the agricultural and economic potential of the Louisiana Territory.[13] Hoping to interest the American Philosophical Society in publishing d’Annemours’s “most excellent account of the Washita River,” Thomas Jefferson sent it to the Society’s librarian, John Vaughan (1756–1841), on May 5, 1805, together with a letter describing the Frenchman as “a man of science, good sense, & truth, . . . [who] may be relied on in whatever facts he states.”[14]

—Robyn Asleson

Texts

- Anonymous, August 17, 1792, Claypoole’s Daily Advertiser (quoted in Thompson 1906: 246)[15]

- “[The Chevalier d’Annemours built] an obelisk to honour the memory of that immortal man—Christopher Columbus . . . in a grove in one of the gardens of the villa Belmont. . . on the 3rd of August, 1792, the anniversary of the sailing of Columbus from Spain.”

- Charles César Robin, c. 1804, description of d’Annemours’s (1966: 140)[16]

- “M. Danemours, the former French Consul at Baltimore, had retired to the district [of Ouachita, Louisiana] several years before my visit and had set up a pretty little house. This man, noted for the nicety of his manners and cultivated mind, used several of his Negroes, whom his excessive indulgence had rendered unused to real work, to lay out an English formal garden in his fields. One must admit that the time and the site were ill chosen. There, where the essentials of life are everyone’s preoccupation, where an opulent nature provides a varied and imposing scenery, who would think of disfiguring a spacious field with a tiny garden of coldly spaced groups of plants?

- “What more beautiful Formal Garden, in this immense forest, than this same field itself, regularly divided into squares of corn, cottons, melons and pumpkins? Near cities, when the eye is fatigued by symmetrical figures, one should there reproduce deliberate irregularities. For, while not far from Paris, I took pleasure in walking in rustic groves, here in Louisiana I delighted in strolling along an avenue of sycamores neatly aligned by the same M. Danemours. In these cool shades I had the illusion of being in my native land.” back up to History

Images

Notes

- ↑ Anne Mézin, Les Consuls de France Au Siècle Des Lumières (1715–1792) (Paris: Ministère des affaires étrangères, Direction des archives et de la documentation, 1998), 398–99, view on Zotero; Wendy Bradley Richter, ed., Memoirs by Charles François Adrien Le Paulmier, Le Chevalier d’Annemours, trans. Samuel Dorris Dickinson (Arkadelphia, AR: Clark County Historical Association and the Institute for Regional Studies, Oachita Baptist University, 1994), 2, view on Zotero; “Notice Sur Le Chevalier Charles François-Adrien le Paulmier d’Annemours,” Maryland Historical Magazine 5 (1910): 38–39, view on Zotero; Henry F. Thompson, “The Chevalier d’Annemours,” Maryland Historical Magazine 1 (1906): 241, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Richter 1994, 2–3, 11–53, view on Zotero; Thompson 1906, 242, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Peter B. Hill, French Perceptions of the Early American Republic, 1783–1793 (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1988), 6, 18, 49, 83, 90–91, 142, 168, view on Zotero; “Notice sur Le Chevalier Charles François-Adrien Le Paulmier d’Annemours,” 1910, 39–43, view on Zotero; Thompson 1906, 243–44, view on Zotero; Francis Wharton, The Revolutionary Diplomatic Correspondence of the United States (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1889), 5:396, view on Zotero.

- ↑ André Michaux, “Journal de André Michaux,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 25, no. 122 (March 1889): 58.

- ↑ Quotation from Samuel Ready Asylum Board report, c. 1887, in Robert S. Wolff, “Industrious Education and the Legacy of Samuel Ready, 1887–1920,” Maryland Historical Magazine (Fall 2000): 312, view on Zotero.

- ↑ See Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Online Catalogue.

- ↑ Richter 1994, 4, view on Zotero; “Notice sur Le Chevalier Charles François-Adrien Le Paulmier d’Annemours,” 1910, 43–45, view on Zotero; Thompson 1906, 246, view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Elleroy Curtis, Christopher Columbus: His Portraits and His Monuments: A Descriptive Catalogue, Part 2 (Chicago: W. H. Lowdermilk Co., 1893), 43–44, view on Zotero; see also Herbert Adams and Henry Wood, Columbus and His Discovery of America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1892), 30–35, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Herbert Adams and Henry Wood, Columbus and His Discovery of America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1892), 30, 70–71, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Sylvester Breard, Early History of Monroe (Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing Company, Inc., 2012), 26–27, view on Zotero; Richter 1994, 4–5, 7, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Breard 2012, 74–75, 172–73, view on Zotero; Anne Butler, The Pelican Guide to Plantation Homes of Louisiana, 8th ed. (Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing Corporation, Inc., 2009), 133, view on Zotero; Richter 1994, 5–6, 64–65, view on Zotero; Ed Lewis, “Monroe Landmark Moving to a New Location,” Monroe News-Star (June 18, 1971), The O’Kelly Family Collection website; Charles François Adrien Le Paulmier le Chevalier d’Annemours, Memoirs by Charles François Adrien Le Paulmier Le Chevalier d’Annemours, ed. Wendy Bradley Richter, trans. Samuel Dorris Dickinson (Arkadelphia, AR : Clark County Historical Association : Institute for Regional Studies, Ouachita Baptist University, 1994), 140, view on Zotero; George Sabo II, “Review of Charles François Adrien Le Paulmier: Le Chevalier d’Annemours,” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 54 (1995): 221, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Although Robin uses the phrase “jardins anglais,” his description makes clear that d’Annemours laid out his gardens in a formal, geometric style, rather than the more natural style associated with English gardens. See Charles César Robin, Voyages Dans L’intérieur de La Louisiane, de La Floride Occidentale, et dans les Isles de La Martinique et de Saint-Domingue, 1802–1806, 2 vols. (Paris: F. Buisson, 1807), 2:338–39, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles François Adrien Le Paulmier, Chevalier d’Annemours “Memoir of Le Paulmier d’Annemours, Former Consul General of France in America, about the Ouachita District,” April 21, 1803, Pierre Clément de Laussat Papers, MSS 125, Box 4, Folder 148, Williams Research Center, Historic New Orleans Collection, view on Zotero; see also Richter 1994, 67–92, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson to John Vaughan, May 5, 1805, Founders Online, National Archives [last update: 2015-02-20].

- ↑ Henry F. Thompson, “The Chevalier d’Annemours,” Maryland Historical Magazine 1 (1906): 241–46 view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles César Robin, Voyage to Louisiana by C. C. Robin, 1803–1805, trans. by Stuart O. Landry Jr. (New Orleans: Pelican Publishing Company, 1966), view on Zotero. The original text reads as follows: “M. Danemours, ancient consul de France à Baltimore, était venu se retirer pendant quelques années dans ce canton, il y avait établit une habitation assez jolie. Cet home estimable par la douceur de ses moeurs, par un esprit cultivé, employait quelques nègres que son excessive indulgence avait déshabitués du travail, à façonner dans son champ des sites de jardins anglais. C’était, il faut en convener, bien mal choisir le lieu et le temps. Là où les premiers besoins de la vie doivent occupier avant tout, où la nature opulente produit avec somptuosité les plus grands effect, recrée toujours sans se repeater, comment s’aviser de défigurer un champ spacieux par de maigres groupes froidement espacés? Quel plus beau jardin anglais au milieu de ces superbes forêts, que ce même champ bien net, bien regularizé en carreaux de maïs, de cotonniers, de melons, de giraumonts. Prés de nos villes, à la bonne heure, où la vue est fatigue de symétriques distributions, recréez-là par des irregularities apparentes. Et, tandis que, non loin de Paris, je me plaisais tant au milieu de ces bosquets agrestes, je me promenais avec délices au Ouachita, sous une belle avenue de platane allignée par les soins du même M. Danemours. Des illusions de ma terre natale me suivaient sous ces ombres solitaires” (Robin 1807, 2: 338–39, view on Zotero).