Difference between revisions of "Shrubbery"

(→Usage) |

A-Whitlock (talk | contribs) |

||

| (113 intermediate revisions by 11 users not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

| + | Generally described as an arrangement of shrubs with the possible inclusion of flowers or trees, the term shrubbery emerged in American usage after 1750, with the fullest descriptions of the feature appearing in the early 19th century. This corresponds with the history of shrubbery in Britain, where in the 18th century it evolved from other related features, such as [[wilderness]], which also employed shrubs, trees, and flowers.<ref>See Mark Laird, ''The Flowering of the Landscape Garden: English Pleasure Grounds, 1720–1800'' (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999), chaps. 3, 4, 7, and 8, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/VHZIWTH3 view on Zotero].</ref> The term “shrubbery” was sometimes used to describe a collection of shrubs (a category of low woody plants with multiple branches). This use of the term is evident in Fanny Kemble’s 1839 account of Butler Island, Georgia. More frequently, however, it indicated a distinct ornamental feature that included not only shrubs but also trees and possibly flowers, and it is this use of the term that this study focuses upon. | ||

| − | + | Given that [[wilderness]]es, [[grove]]s, [[thicket]]s, and [[clump]]s could all be composed of the same materials as shrubberies, it is not surprising that a certain degree of ambiguity surrounded the term in 18th- and early 19th-century gardening literature. This confusion is exemplified by the elision of the terms “shrubbery” and “bosquet” in 1800 by an observer of Adrian Valeck’s estate in Baltimore. As late as 1841, [[Robert Buist]] conflated these terms in his reference to [[thicket]] as a mass of shrubbery. As John Abercrombie and James Mean noted in 1817, this ambiguity was compounded by the difficulty in determining the boundaries of the [[flower garden]] and the shrubbery since the two features often adjoined each other and employed similar plant materials. For Abercrombie and Mean, shrubbery was characterized by a predominance of shrubs with only a few flowers, a distinction that also made shrubberies different from [[grove]]s. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The key elements that distinguished shrubberies from [[wilderness]]es (both of which utilized shrubs and flowers), were siting, plant arrangement, and treatment of plant material. In general, wildernesses were composed of trees under-planted with shrubs and cut through by [[walk]]s. In contrast, shrubberies featured plants arranged in graduated heights (from lowest to highest) and were intended as frames or [[border]]s to [[walk]]s. Such distinctions help to clarify Alexander Gordon’s 1849 comment that the way to transform “magnificent groves of magnolias” into “a perfect ''facsimile'' of an English shrubbery would be to introduce [[walk]]s, and judiciously thin out and regulate the mass.” | |

| − | The | + | The graduated plantings commonly featured in shrubberies allowed the maximum display of plants, a technique that derived from 18th-century flower [[border]]s and [[wilderness]] fringes. In 1804, for example, Gardiner and Hepburn recommended planting shorter shrubs in front of taller ones, in order to exhibit each “to most advantage.” In 1841, Buist instructed his reader to keep each plant “distinct, one from another, in order that they may be the better shown off.” |

| − | + | Although the term “shrubbery” was often ambiguously used, examples of specific uses abound in American gardening literature, as demonstrated by the case of [[Mount Vernon]]. George Washington planted shrubberies along the serpentine [[walk]]s that outlined the west lawn. These shrubberies not only bordered the [[walk]]s to the north and south, but also connected the wilderness area (adjacent to the western terminus of the lawn) to the house and its outlying structures. This use of shrubberies was consistent with the guidelines set forth by prevailing treatise writers, such as William Marshall, whose ''On Planting and Rural Ornament'' (1803) Washington owned. Marshall maintained that shrubberies were more appropriate for establishing connections among garden features than were [[wood]]s, [[grove]]s, or [[thicket]]s, which belonged to the broader landscape of hills and valleys. Similarly, the American garden writer [[Bernard M’Mahon]], in his ''American Gardener’s Calendar'' (1806), explicitly stated that shrubberies should be used to frame [[walk]]s or [[lawn]]s. The curving sweeps of Washington’s shrubbery also exemplified the [[Modern_style|modern]] (or natural) style espoused by most late 18th- and early 19th-century treatise writers. | |

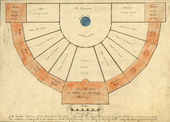

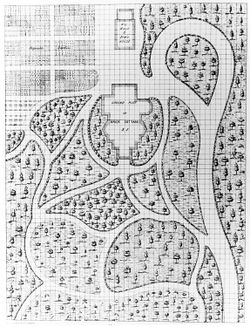

| − | + | [[File:1270.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 1, Solomon Drowne, ''[[Botanic Garden]], 1818'', 1818. “Shrubbery” is marked in the hemicycle plat.]] | |

| + | At [[Mount Vernon]], Washington also designated a second area as a shrubbery, as revealed in the instructions he sent in 1776 to his nephew and estate manager Lund Washington. In his letter, the elder Washington recommended that [[grove]]s of trees be planted on each side of the house. He also referred to the southern grove, which was made up of ornamental trees under-planted with “wild flowering shrubs,” as a shrubbery. In its massing of vegetation and distinct shape, this shrubbery harked back to wildernesses. But the varied plant material of the shrubbery—ornamental trees interspersed with evergreens and shrubs—suggested a graduated arrangement in accordance with the directions of contemporary treatises. | ||

| − | + | Washington’s desire for the “clever kind of Trees” in his shrubbery illustrates the frequent use of shrubbery to draw attention to exotic, rare, or highly ornamental shrubs. Treatise writers underscored how a shrubbery could, in [[Bernard M’Mahon|Bernard M'Mahon's]] words, “display a beautiful diversity of foliage and flowers,” by including a list of recommended trees, shrubs, and herbaceous flowers. The inclusion of a shrubbery in Solomon Drowne’s plan (1818) for a [[botanic garden]] exemplifies this use [Fig. 1]. This notion of a shrubbery was most fully developed by [[J. C. Loudon]] in his theory of the [[gardenesque]], which dictated graduated plantings, arranged from low herbaceous plants to taller ornamental trees, and a distinct separation of each specimen in order to emphasize the “display of shrubs valued for their beauty or fragrance.” | |

| − | + | Loudon’s 1826 text also alerts us to the wide range of style terminology used in the early 19th century to describe different methods of arranging and situating the shrubbery, such as “[[Geometric_style|geometric]],” “systematic” (or “methodical”), “Chinese,” “[[gardenesque]],” “mingled,” and “select” (or “grouped”). The latter two styles were the most significant: “mingled” referred to rhythmically mixing species according to blooming schedules within each carefully graduated row, whereas “select” referred to massing by genus, species, or variety with gradual blending from one type to the next. In America, such terms were not always used with great precision. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that references to “mixed” or “mingled” arose much more often in garden literature than in common usage. | |

| − | |||

| − | Loudon’s | + | <div id="Fig_2"></div>[[File:0938.jpg|thumb|Fig. 2, James E. Teschemacher, “A [[Greenhouse|green-house]] constructed at the centre of a cottage,” in ''Horticultural Register, and Gardener’s Magazine'' 1 (May 1, 1835): opp. 157. On the left, a shrubbery conceals the entrance to the stables. [[#Fig_2_cite|Back to text]]]] |

| + | [[J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon|Loudon’s]] commentary also points out the predominant use of shrubberies in order to frame the sides of [[walk]]s, to screen out unpleasant [[view]]s, or to link together visually certain aspects of the pleasure ground or flower garden. The function of screening is clearly illustrated by John Trumbull’s inscription of his landscape plan for Yale College (1793), where he instructed to “conceal as much as possible,” the privies, or, as he called them, “The Temples of Cloacina,” a reference to the ancient sewer in Rome. [[André Parmentier]] placed shrubberies along the [[walk]]s at his [[nursery]], particularly those connecting various ornamental features of the garden, such as the [[Rustic_style|rustic]] [[arbor]] and the “French saloon.”<ref>Anonymous, “Parmentier’s Horticultural Garden,” ''New England Farmer, and Horticultural Journal'' 7, no. 11 (October 3, 1828): 84–85, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/ZC2KF67E view on Zotero].</ref> These shrubberies also screened out the [[nursery]] [[bed]]s and vineyards. | ||

| − | + | James E. Teschemacher, writing in the ''Horticultural Register'' in 1835, explained at length the appropriateness of using shrubbery to hide the vegetable or [[kitchen garden]] and to obscure the boundaries of a property, making the grounds appear larger. Teschemacher’s lithograph [Fig. 2] illustrates the use of shrubberies positioned along walks to lead the viewer’s attention away from undesirable working areas, such as the vegetable garden, and toward the more appealing [[flower garden]]. Like his predecessors, mid-19th century garden designer William H. Ranlett positioned shrubberies along [[walk]]s, roads, or around the perimeter of houses, thus ensuring that homes built in an urban or suburban context could enjoy a display of flowering vegetation. | |

| − | + | By the 1840s, shrubbery had developed as a distinct garden feature defined by graduated, intermixed vegetation; placement along [[walk]]s, roads, [[flower garden]]s, and [[lawn]]s; and use as a linking and screening device. The latter two characteristics were shared with [[hedge]]s, but hedges were understood to be generally uniform in size and species and densely planted to create an impenetrable barrier. More importantly, unlike the [[hedge]], the formation of the shrubbery was driven by the impulse to display prized plants. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | —''Anne L. Helmreich'' | |

| − | |||

| − | + | <hr> | |

==Texts== | ==Texts== | ||

| + | ===Usage=== | ||

| + | *[[Thomas Jefferson|Jefferson, Thomas]], 1771, describing [[Monticello]], [[plantation]] of [[Thomas Jefferson]], Charlottesville, VA (1944: 27)<ref>Thomas Jefferson, ''The Garden Book'', ed. Edwin M. Betts (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1944), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/8ZA5VRP5/ view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“The Open Ground on the West—a '''shrubbery''' | ||

| + | :“Shrubs—(Not exceeding a growth of 10. f.). Alder—Bastard indigo. flowering Amorpha—Barberry—Cassioberry. Cassine.—Chinquapin— Jersey-tea. F. Ceanothus—Dwarf Cherry. F. Cerasus. 5. Clethra—Cockspur hawthorn, or haw. Crataegus. 4. Laurel—Scorpion Sena. Emerus— Hazel.—Althea F.—Callicarpa—Rose—Wild honeysuckle—Sweet-briar—Ivy. | ||

| + | :“Trees.—Lilac—Wild Cherry—Dogwood— Redbud—Horse chestnut—Catalpa—Magnolia— Mulberry—Locust—Honeysuckle—Jessamine— Elder—Poison oak—Haw—Fig. | ||

| + | :“Climbing shrubby plants.—Trumpet flower—Jasmine—Honeysuckle. | ||

| + | :“Evergreens.—Holly—Juniper—Laurel—Magnolia—Yew. | ||

| + | :“Hardy perennial flowers.—Snapdragon— Daisy—Larkspur—Gilliflower—Sunflower— Lily—Mallow—Flower de luce—Everlasting pea—Piony—Poppy—Pasque flower—Goldylock, Trollius=Anemone—Lilly of the Valley— Primrose—Periwinkle—Violet—Flag.—(''Account Book 1771''.)” | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | *Washington, George, August 19, 1776, in a letter to Lund Washington, describing [[Mount Vernon]], [[plantation]] of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (quoted in Riley 1989: 7)<ref>John P. Riley, ''The Icehouses and Their Operations at Mount Vernon'' (Mount Vernon, VA: Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, 1989), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/76PVTIZM view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“I mean to have groves of Trees at each end of the dwelling House. . . these Trees to be Planted without any order or regularity (but pretty thick, as they can at any time be thin’d) and to consist that at the North end, of locusts altogether. and that at the South, of all the clever kind of Trees (especially flowering ones) that can be got, such as Crab apple, Poplar, Dogwood, Sasafras, Laurel, Willow (especially yellow and Weeping Willow, twigs of which may be got from Philadelphia) and many others which I do not recollect at present; these to be interspersed here and there with ever greens such as Holly, Pine, and Cedar, also Ivy; to these may be added the Wild flowering Shrubs of the larger kind, such as the fringe Trees and several other kinds that might be mentioned. It will not do to plant the Locust Trees at the North end of the House till the Framing is up. . . But nothing need prevent planting the '''Shrubbery''' at the other end of the House. Whenever these are Planted they should be Inclosd, which may be done in any manner till I return; or rather by such kind of fencing as used to be upon the Ditch running towards Hell hole. . . If I should ever fulfil my Intention it will be to Inclose it properly; the [[Fence]] now described is only to prevent Horses & ca. injuring the young Trees in their growth.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | *Washington, George,1785, describing [[Mount Vernon]], [[plantation]] of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (Jackson and Twohig 1978: 4:94, 97, 99)<ref>George Washington, ''The Diaries of George Washington'', ed. Donald Jackson and Dorothy Twohig, 6 vols. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1978), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/9ZIIR3FT view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“[February 22] I also removed from the [[Wood]]s and old fields, several young Trees of Sassafras, Dogwood, & red bud, to the '''Shrubbery''' on the No. Side the grass plat. . . | ||

| + | :“Planted the remainder of the Ash Trees—in the Serpentine [[walk]]s—the remainder of the fringe trees in the '''Shrubberies'''—all the black haws—all the large berried thorns with a small berried one in the middle of each [[clump]]—6 small berried thorns with a large one in the middle of each clump—all the swamp red berry bushes & one [[clump]] of locust trees. . . | ||

| + | :“[March 3] Planted the remainder of the Locusts—Sassafras—small berried thorn & yellow Willow in the '''Shrubberies''', as also the red buds— a honey locust and service tree by the South Garden House. Likewise took up the clump of Lilacs that stood at the Corner of the South Grass [[plat]] & transplanted them to the clusters in the '''Shrubberies''' & standards at the south Garden [[gate]]. The Althea trees were also planted. . . | ||

| + | :“Employed myself the greatest part of the day in pruning and shaping the young plantation of Trees & Shrubs. . . | ||

| + | :“[March 7] Planted all my Cedars, all my Papaw, and two Honey locust Trees in my '''Shrubberies''' and two of the latter in my [[grove]]s—one at each (side) of the House and a large Holly tree on the Point going to the Sein landing.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

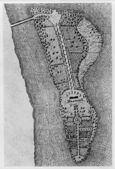

| + | [[File:0100.jpg|thumb|Fig. 3, John Trumbull, Plan for Old Brick Rowe, 1793. The three [[square]] privies are surrounded by the shrubbery.]] | ||

| + | *Trumbull, John, 1792, describing Yale College, New Haven, CT (Yale University Library, Manuscripts and Archives, Yale Picture Collection, 48A-46, box 1, folder 2) | ||

| + | :“The [[Temple]]s of Cloacina (which it is too much the custom of New England to place conspicuously,) I would wish to have concealed as much as possible, by planting a variety of Shrubs, such as Laburnums, Lilacs, Roses, Snowballs, Laurels. &c, &c—a gravel [[walk]] should lead thro [''sic''] the '''Shrubbery''' to those buildings. | ||

| + | :“The Eating Hall should likewise be hidden as much as the space will admit with similar shrubs.” [Fig. 3] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | *Clitherall, Eliza Caroline Burgwin (Caroline Elizabeth Burgwin), active 1801, describing the Hermitage, seat of John Burgwin, Wilmington, NC (quoted in Flowers 1983: 125)<ref>John Flowers, “People and Plants: North Carolina’s Garden History Revisited,” ''Eighteenth Century Life'' 8 (1983): 117–29, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/FCVW8GHV view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“The Gardens were large, and laid out in the [[English style]]—a Creek wound thro’ the largest, upon its banks grew native '''shrubbery'''.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | *Anonymous, June 14, 1800, describing in the ''Federal Gazette'' the estate of Adrian Valeck, Baltimore, MD (quoted in Sarudy 1989: 136)<ref>Barbara Wells Sarudy, “Eighteenth-Century Gardens of the Chesapeake,” ''Journal of Garden History'' 9 (1989): 104–59, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/PGSNXHMJ view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“A large garden in the highest state of cultivation, laid out in numerous and convenient [[walk]]s and [[square]]s bordered with [[espalier]]s. . . Behind the garden in a grove and '''shrubbery''' or bosquet planted with a great variety of the finest forest trees, oderiferous & other flowering shrubs etc.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | *Hamilton, Alexander, c. 1801–4, describing Hamilton Grange, estate of Alexander Hamilton, New York, NY (quoted in Lockwood 1931: 1:263)<ref>Alice B. Lockwood, ed., ''Gardens of Colony and State: Gardens and Gardeners of the American Colonies and of the Republic before 1840'', 2 vols. (New York: Charles Scribner’s for the Garden Club of America, 1931), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/JNB7BI9T view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“If practicable in time I should be glad some laurel should be planted along the edge of the '''shrubbery''' and round the [[clump]] of trees near the house; also sweet briars and [illegible]. | ||

| + | :“A few dogwood trees not large, scattered along the margin of the [[grove]] would be very pleasant, but the fruit trees there must be first removed and advanced in front.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | *Taylor, General James, 1805 [?], describing [[Mount Vernon]], [[plantation]] of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (quoted in Norton and Schrage-Norton 1985: 148)<ref>John D. Norton and Susanne A. Schrage-Norton, “The Upper Garden at Mount Vernon Estate—Its Past, Present, and Future: A Reflection on 18th Century Gardening. Phase II: The Complete Report” (Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association Library, 1985), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/3R9Z6WZT view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“The flower and '''shrubbery''' gardens on the north side of the [[avenue]] are tastefully laid out in serpentine [[walk]]s and [[square]]s bordered with dwarf box-wood interspersed with handsome flowering shrubs with ornamental trees around the exterior of the inclosure.” | ||

| − | |||

| − | * | + | *Drayton, Charles, November 2, 1806, describing [[The Woodlands]], seat of [[William Hamilton]], near Philadelphia, PA (1806: 55)<ref> Charles Drayton, “The Diary of Charles Drayton I, 1806,” Drayton Papers, MS 0152, Drayton Hall, SC, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/HAARCGXN view on Zotero].</ref> |

| + | : “The <u>Garden</u> consists of a large verdant [[lawn]] surrounded by a belt of [[walk]], & '''shrubbery''' for some distance.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Ripley, Samuel, 1815, describing Gore Place, summer home of Christopher and Rebecca Gore, Waltham, MA (1815: 273)<ref>Samuel Ripley, “A Topographical and Historical Description of Waltham, in the County of Middlesex, Jan. 1, 1815,” ''Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society'' 3 (January 1815): 261–84, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/7INJ3GDV view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“It is situated in the centre of pleasant grounds, tastefully laid out, surrounded by a [[walk]] of a mile in circuit, intersected by several other [[walk]]s, on all of which are growing trees and '''shrubbery''' of various kinds.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | *Warden, David Bailie, 1816, describing Analostan Island, seat of Gen. John Mason, Washington, DC (quoted in Phillips 1917: 49)<ref>Philip Lee Phillips, ''The Beginnings of Washington: As Described in Books, Maps, and Views'' (Washington, DC: The author, 1917), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/QXZXNN8N view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | :"ANNALOSTAN ISLAND | ||

| + | : . . . Annalostan Island is evidently of modern formation. . . The highest [[eminence]], on which the house stands, is fifty feet above the level of the river. The common tide rises to the height of three feet. I can never forget how de-lighted I was with my first visit to this island. The amiable ladies whom I had the pleasure to accompany, left their carriage at Georgetown, and we walked to the mansion-house under a delicious shade. The blossoms of the cherry, apple, and peach trees, of the hawthorn and aromatic '''shrubs''', filled the air with their fragrance. . . The house, of a simple and neat form, is situated near that side of the island which commands a [[view]] of the Potomac, the President's House, Capitol, and other buildings. The garden, the sides of which are washed by the waters of the river, is ornamented with a variety of trees and '''shrubs''', and, in the midst, there is a [[lawn]] covered with a beautiful verdure. The [[Summerhouse|summer-house]] is shaded by oak and lin-den-trees, the coolness and tranquility of which invite to contemplation. The refresh-ing breezes of the Potomac, and the gentle murmuring of its waters against the rocks, the warbling of birds, and the mournful as-pect of the weeping-willows, inspire a thousand various sensations. What a delicious shade- | ||

| + | |||

| + | :"Ducere sol[l]icitae jucunda oblivia vitae" | ||

| + | |||

| + | :The [[view]] from this spot is delightful. It embraces the [[picturesque]] banks of the Po-tomac, a portion of the city, and an expanse of water, of which the bridge terminates the [[view]]. . . A few feet below the [[Summerhouse|sum-mer-house]] the rocks afford the [[seat]]s, where those who are fond of fishing may indulge in this amusement. From the [[portico]] on the oppo-site [139] side of the house, Georgetown, Calorama, the beautiful [[seat]] of Joel Barlow, Esq. and the adjacent finely-wooded hills, appear a [[vista]]." | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | *Latrobe, Mary Elizabeth, April 18, 1820, describing the Latrobe home, New Orleans, LA (1951: 180–81)<ref>Benjamin Henry Latrobe, ''Impressions Respecting New Orleans: Diaries and Sketches, 1818–1820'', ed. Samuel Wilson (New York: Columbia University Press, 1951), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/MJS5EE69/ view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | :“. . . the house as far from the river as across Baltimore street, filled between with a '''shrubbery''' consisting of about 4 Myrtles (the small leaf’d) 20 feet high, about, 8 Oleanders still higher, forty rose bushes of an immense size, of different sorts, 4 Monstrous Musk rose bushes, half a doz. large pomegranate trees.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | *Hall, Capt. Basil, 1828, describing a plantation he visited during his trip from Charleston, SC, to Savannah, GA (quoted in Jones 1957: 98)<ref>Katharine M. Jones, ''The Plantation South'' (New York: Bobbs-Merrill, 1957), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/AT62T7KC view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“From the drawing-room, we could walk into a [[verandah]] or [[piazza]], from which, by a flight of steps, we found our way into a [[flower garden]] and '''shrubbery''', rich with orange trees, laurels, myrtles, and weeping willows, and here and there a great spreading aloe.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | *Martineau, Harriet, 1835, describing Marietta, OH (1838: 2:73)<ref>Harriet Martineau, ''Retrospect of Western Travel,'' 2 vols. (London: Saunders and Otley, 1838), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/H2BW5FRU view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“This island was purchased, about thirty-five years ago, by an Irish gentleman, named Herman Blennerhassett, whose name the island has since borne. This gentleman took his beautiful and attached wife to his new property, and their united tastes made it such an abode as was never before and has never since been seen in the United States. '''Shrubberies''', [[conservatories]], and gardens ornamented the island, and within doors there was a fine library, philosophical apparatus, and music-room.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | *Lester, N., November 30, 1837, describing the Hermitage, estate of Andrew Jackson, Nashville, TN (LHA Research #231) | ||

| + | :“The General has a very fine garden; I culled some choice seeds which I will divide with you the first opportunity. The garden is tastefully laid off in [[plat]]s, ornamented with various kinds of flowers and '''shrubbery'''. The tomb of his lamented lady is in one corner of the garden, but a short distant from his dwelling. It is surrounded by rose bushes, and the weeping willow, and covered by a plain [[summer-house]].” | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | *Kemble, Fanny, January 1839, describing her husband’s plantations on Butler Island, GA (1984: 56)<ref>Frances Anne Kemble, ''Journal of a Residence on a Georgian Plantation in 1838–1839'', ed. John A. Scott (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1984), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/UWZQAT2D/ view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“As I skirted one of these [[thicket]]s today, I stood still to admire the beauty of the '''shrubbery'''. Every shade of green, every variety of form, every degree of varnish, and all in full leaf and beauty in the very depth of winter. The stunted dark-colored oak; the Magnolia bay. . . which grows to a very great size; the wild myrtle, a beautiful and profuse shrub, rising to a height of six, eight, and ten feet, and branching on all sides in luxuriant tufted fullness; most beautiful of all, that pride of the South, the Magnolia ''grandiflora'', whose lustrous dark green perfect foliage would alone render it an object of admiration, without the queenly blossom whose color, size, and perfume are unrivaled in the whole vegetable kingdom.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:1118.jpg|thumb|Fig. 4, W. H. Bartlett, “Undercliff Near Cold-Spring. (The Seat of General George P. Morris),” in Nathaniel Parker Willis, ''American Scenery'' (1840), vol. 2, pl. 11.]] | ||

| + | *Willis, Nathaniel Parker, 1840, describing Undercliff, seat of Gen. George P. Morris, near Cold Spring, NY (1840: 233)<ref>Nathaniel Parker Willis, ''American Scenery; Or, Land, Lake and River Illustrations of Transatlantic Nature'' (London: G. Virtue, 1840), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/FB4EQ56M view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“In front, a circle of greensward is refreshed by a [[fountain]] in the centre, gushing from a Grecian [[vase]], and encircled by ornamental '''shrubbery'''; from thence a gravelled [[walk]] winds down a gentle declivity to a second plateau, and again descends to the entrance of the carriage road, which leads upwards along the left slope of the hill, through a noble forest, the growth of many years, until suddenly emerging from its sombre shades, the visitor beholds the mansion before him in the bright blaze of day.” [Fig. 4] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | *Anonymous, June 1840, “Notices of Greenhouses and Hot-houses, in and near Philadelphia,” describing [[The Woodlands]], seat of William Hamilton, near Philadelphia, PA (''Magazine of Horticulture'' 6: 201)<ref>Anonymous, “Notices of Greenhouses and Hot-houses, in and near Philadelphia,” ''Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs'' 6, no. 6 (June 1840): 201–3, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/A352BDPC view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“The '''shrubbery''', for want of attention, had sprung into all sorts of shapes, and bore evident marks of the rude hands of the rabble who passed them by in the season of bloom.” | ||

| + | |||

| − | + | *B., P., January 1844, “Progress of Horticulture in Rochester, N.Y.” (''Magazine of Horticulture'' 10: 17)<ref>B. P., “Progress of Horticulture in Rochester, N.Y.,” ''Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs'' 10, no. 1 (January 1844): 15–19, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/W3UKEX82/q/Progress%20of%20Horticulture%20in%20Rochester view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“[[Flower garden]]s and '''shrubberies''' are no longer objects of amazement; [[avenue]]s of forest trees are not uncommon sights in the vicinity of dwellings; in fact the general neatness that pervades this beautiful section of country cannot fail to suggest to the traveller the steady march of taste and refinement, and the progress, though slow, of that art that transforms the wildest forest into a very Eden.” | |

| − | : | ||

| − | : | ||

| − | |||

| − | : | ||

| − | * | + | *Perkins, John, December 14, 1845, describing his nursery in New Jersey (Peabody Essex Institute, Phillips Library, Lee Family Papers, MS 129, box 1, folder 5) |

| + | :“I am a nurseryman In New Jersey. . . I have a large collection of fruit trees on hand. . . Besides '''shrubery''' & ornamental trees of different varieties.” | ||

| − | |||

| + | *[[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing, Andrew Jackson]], October 1847, describing [[Montgomery Place]], country home of Mrs. Edward (Louise) Livingston, Dutchess County, NY (quoted in Haley 1988: 52)<ref>Jacquetta M. Haley, ed., ''Pleasure Grounds: Andrew Jackson Downing and Montgomery Place'' (Tarrytown, NY: Sleepy Hollow Press, 1988), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/SSZXJFSC view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“Passing under neat and tasteful [[Arch|archways]] of wirework, covered with rare climbers, we enter what is properly | ||

| + | :“THE [[FLOWER GARDEN]]. . . | ||

| + | :“The whole garden is surrounded and shut out from the [[lawn]], by a belt of '''shrubbery''', and above and behind this, rises, like a noble framework, the background of trees of the [[lawn]] and the [[Wilderness]]. If there is any prettier [[flower-garden]] scene than this ensemble in the country, we have not yet had the good fortune to behold it.” | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Earle, Pliny, January 1848, describing Bloomingdale Asylum for the Insane, New York, NY (''Journal of Medicine'' 10: 60) | |

| − | : | + | :“The farm contains about fifty-five acres, and is bounded, on its western side, by the Blooming-dale road. About thirty acres of it is under high cultivation, portions being devoted to grass, vegetables, and ornamental '''shrubbery'''.” |

| − | : | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | + | *Town Council of the Borough of West Chester, March 13, 1848, resolution in memory of [[Humphry Marshall]], Marshallton, West Chester, PA (quoted in Darlington 1849: 492)<ref>William Darlington, ''Memorials of John Bartram and Humphry Marshall: With Notices of Their Botanical Contemporaries'' (Philadelphia: Lindsay & Blakiston, 1849), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/TKNVQG76 view on Zotero].</ref> |

| + | :“Whereas it has been deemed expedient and proper to improve the public [[Square]], on which the upper reservoir connected with the Waterworks of the borough is situated, by laying out the same in suitable [[walk]]s, and introducing various ornamental trees and '''shrubbery'''.” | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | *[[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing, Andrew Jackson]], 1849, describing [[Hyde Park]], seat of [[David Hosack]], on the Hudson River, NY (1849; repr., 1991: 443)<ref>A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, ''A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening'', 4th ed. (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1991), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/K7BRCDC5 view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“Those who have seen the '''shrubbery''' at ''[[Hyde Park]]'', the residence of the late [[Dr. Hosack]], which borders the [[walk]] leading from the mansion to the [[hot-house]]s, will be able to recall a fine example of this mode of mingling woody and herbaceous plants. The belts or [[border]]s occupied by the [[shrubbery]] and [[flower-garden]] there, are perhaps from 25 to 35 feet in width, completely filled with a collection of shrubs and herbaceous plants; the smaller of the latter being quite near the walk; these succeeded by taller species receding from the front of the [[border]], then follow shrubs of moderate size, advancing in height until the background of the whole is a rich mass of tall shrubs and trees of moderate size. The effect of this belt on so large a scale, in high keeping, is remarkably striking and elegant.” | ||

| − | |||

| − | : | + | *Gordon, Alexander, June 1849, “Gardens and Gardening in Louisiana,” describing the residence of Mr. Valcouraam, near New Orleans, LA (''Magazine of Horticulture'' 15: 247–48)<ref>Alexander Gordon, “Remarks on Gardens and Gardening in Louisiana,” ''Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs'' 15, no. 6 (June 1849): 245–49, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/HNZQV4FE/q/gardens%20and%20gardening view on Zotero].</ref> |

| + | :“For instance, within a few minutes walk from where I now write, I could find magnificent [[grove]]s of magnolias (now in full bloom,) with an abundance of choice trees and shrubs. All that would be required to form the scene into a perfect ''facsimile'' of an English '''shrubbery''' would be to introduce [[walk]]s, and judiciously thin out and regulate the mass.” | ||

| − | * | + | *Committee on the Capitol Square, Richmond City Council, July 26, 1851, describing John Notman’s plans for the Capitol Square, Richmond, VA (quoted in Greiff 1979: 162)<ref>Constance Greiff, ''John Notman, Architect, 1810–1865'' (Philadelphia: Athenaeum of Philadelphia, 1979), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/SXT2RI6Z view on Zotero].</ref> |

| + | :“The most beautiful feature of the contemplated alterations of the [[Square]], however, will be found in the arrangement of the trees and '''shrubbery'''. Instead of planting these in parallel rows, like an ordinary [[orchard]] some attention will be paid to [[landscape gardening]]—[[grove]]s, [[arbour]]s, [[parterre]]s, and [[fountain]]s will combine to render the [[Square]] a place of delightful resort.” | ||

| − | |||

| + | ===Citations=== | ||

| + | *Whately, Thomas, 1770, ''Observations on Modern Gardening'' (1770; repr., 1982: 29–30)<ref>Thomas Whately, ''Observations on Modern Gardening'', 3rd ed. (1770; repr., London: Garland, 1982), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/QKRK8DCD/ view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“But there are besides, sometimes in trees, and commonly in shrubs, still more minute varieties. . . But all these inferior varieties are below our notice in the consideration of great effects: they are of consequence only where the [[plantation]] is near to the sight; where it skirts a home scene, or [[border]]s the side of a [[walk]]: and in a '''shrubbery''', which in its nature is little, both in style and in extent, they should be anxiously sought for.” | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Marshall, Charles, 1799, ''An Introduction to the Knowledge and Practice of Gardening'' (1799: 1:113–14)<ref>Charles Marshall, ''An Introduction to the Knowledge and Practice of Gardening'', 1st American ed., 2 vols. (Boston: Samuel Etheridge, 1799), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/DVB7T4I2 view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | : “A | + | :“A ''regularity'' in planting '''shrubs''' is not necessary as to lines, but is rather to be avoided, except just in the front, where there should always be some low ones, and a border for ''flowers'', chiefly of the ''spring'', as summer ones are apt to be drawn up weak, if the '''shrubbery''' [[walk]]s are not very wide. The flowers should be of the lowest growth, and rather bulbous rooted. . . In open '''shrubberies''' an edging of ''strawberries'' is proper, and the hautboy preferable.” |

| − | * | + | *Forsyth, William, 1802, ''A Treatise on the Culture and Management of Fruit Trees'' (1802: 144–45)<ref>William Forsyth, ''A Treatise on the Culture and Management of Fruit Trees'' (Philadelphia: J. Morgan, 1802), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/ZSNDFTE9 view on Zotero].</ref> |

| + | :“I have recommended the practice of intermixing fruit-trees in '''shrubberies''' and [[plantation]]s of this kind to several gentlemen, who have adopted it with success. While the fruit-trees are in flower, they are a great ornament to the '''shrubberies'''; and in summer and autumn the different colours of the fruit have a beautiful appearance. Add to this the advantage of a plentiful supply of fruit for the table, and for making cider and perry; and if some cherries are interspersed among them, they will be food for birds, and be the means of preventing them from destroying your finer fruit in the orchard or garden.” | ||

| − | |||

| + | *Marshall, William, 1803, ''On Planting and Rural Ornament'' (1803: 1:256, 280)<ref>William Marshall, ''On Planting and Rural Ornament: A Practical Treatise. . . '', 2 vols. (London: G. and W. Nicol, G. and J. Robinson, T. Cadell, and W. Davies, 1803), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/K48D75JJ/ view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“[[WOOD]]S, [[Grove]]s, and extensive [[Thicket]]s, are more particularly adapted to the sides of hills, and elevated situations: detached Masses, Groups, and Single Trees, to the lower grounds. . . The '''Shrubery''' [''sic''] depends more on the given accompaniments, than on its own natural situation. . . | ||

| + | :“IF the house be stately, and the adjacent country rich and highly cultivated, a '''shrubery''' [''sic''] may intervene, in which Art may shew her utmost skill.” | ||

| − | |||

| − | : | + | *Gardiner, John, and David Hepburn, 1804, ''The American Gardener'' (1804: 108)<ref>John Gardiner and David Hepburn, ''The American Gardener, Containing Ample Directions for Working a Kitchen Garden Every Month in the Year, and Copious Instructions for the Cultivation of Flower Gardens, Vineyards, Nurseries, Hop Yards, Green Houses and Hot Houses'' (Washington, DC: Printed by Samuel H. Smith, 1804), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/GKECKRIQ view on Zotero].</ref> |

| + | :“Plant roses, honeysuckles, jasmins, lilacs, double hawthorn, cherry blossom, and other hardy shrubs, when the weather is mild.—In forming a '''shrubbery''', plant the lowest shrubs in front of [[clump]]s, and the tallest most backward, three to six feet apart, according to the bulk the shrubs grow. They will thus appear to most advantage.” | ||

| − | * | + | *[[Bernard M’Mahon|M’Mahon, Bernard]], 1806, ''The American Gardener’s Calendar'' (1806: 55, 62)<ref>Bernard M’Mahon, ''The American Gardener’s Calendar: Adapted to the Climates and Seasons of the United States. Containing a Complete Account of All the Work Necessary to Be Done. . . for Every Month of the Year. . .'' (Philadelphia: Printed by B. Graves for the author, 1806), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/HU4JIS9C view on Zotero].</ref> |

| + | :“For instance, a grand and spacious open [[lawn]], of grass-ground, is generally first presented immediately to the front of the mansion, or main habitation. . . widening gradually outwards, and having each side embellished with plantations of '''shrubbery''', [[clump]]s, [[thicket]]s, &c. . . . and in the interior divisions of the ground, serpentine winding [[walk]]s, and elegant grass openings, ranged various ways, all bordered with '''shrubberies''', and other tree and shrub plantations, flower compartments, &c. disposed in a variety of different rural forms, in easy bendings, concaves, and straight ranges, occasionally; with intervening breaks or opens of grass-ground; both to promote rural diversity, and for communication and [[prospect]] to the different divisions. . . | ||

| + | :“All the [[plantation]] compartments of '''shrubbery''', [[wilderness]], &c. should be planted with some considerable variety of different sorts of trees, shrubs, and flowers, artfully disposed in varied arrangements; the tallest behind, the lowest forward, and the different sorts so intermixed, as to display a beautiful diversity of foliage and flowers, disposing the more curious kinds contiguous to the principal [[walk]]s and [[lawn]]s. . . | ||

| + | :“In planting the several '''shrubbery''' [[clump]]s, &c. some may be entirely of trees; but the greater part an assemblage of trees and shrubs together; some entirely of the low shrub kind, in different situations, between, and in front of the larger growths; likewise should intersperse most of the '''shrubbery''' and [[wilderness]] compartments, with a variety of hardy herbaceous flowery plants of different growths, having also here and there [[clump]]s entirely of herbaceous perennials: the distribution or arrangement of the [[clump]]s, and other divisions of the different kinds, both trees, shrubs, and flowers, should be so diversified, as to exhibit a proper contrast, and a curious variation of the general scene.” | ||

| − | |||

| + | *Abercrombie, John, with James Mean, 1817, ''Abercrombie’s Practical Gardener'' (1817: 337–38)<ref>John Abercrombie, ''Abercrombie’s Practical Gardener Or, Improved System of Modern Horticulture'' (London: T. Cadell and W. Davies, 1817), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/TH54TADZ view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“The lines of distinction between the [[Flower Garden]], the '''Shrubbery''', and the [[Pleasure Ground]], can neither be positively marked, nor constantly observed, in treating the subjects which may seem to fall under one of these heads more properly than under either of the others. The flowering shrubs connect the two former. For instance, can there be such an exact partition between the [[Flower Garden]] and the '''Shrubbery''', as would destroy their communication, while the plant which bears the beautiful rose belongs, in a catalogue of names, to the latter department? Or can we prevent the [[Pleasure Ground]] from running into the [[Flower Garden]] and '''Shrubbery''', so as scarcely to know where one begins and the other ends, as long as a [[Pleasure Ground]], with the most happy diversity of [[lawn]]s, [[wood]], and water, would be incomplete without flowers and shrubs? | ||

| + | :“The substantial difference between the two former [ [[Flower Garden]] and '''Shrubbery''' ], lies in the proportion in which the two classes of plants are cultivated: hence, where a great preponderance of plants without woody stems display their bloom, the characteristics of a [[Flower Garden]] seem obvious enough: if another spot is almost covered with [[clump]]s of shrubs, and merely dotted with a few creeping flowers, it will be termed, without hesitation, a '''Shrubbery'''.” | ||

| − | |||

| − | : | + | *Nicol, Walter, 1823, ''The Villa-Garden Directory'' (1823: 3–4)<ref>Walter Nicol, ''The Villa-Garden Directory, or Monthly Index of Word, to Be Done in Town and Villa Gardens, Shrubberies and Parterres'' (Edinburgh: Archibald Constable, 1823), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/DF9Z32E5 view on Zotero].</ref> |

| + | :“. . . care should be taken, in the disposition of the '''shrubberies''', or other [[plantation]]s, to preserve the best [[view]]s. The whole should appear light and airy; nor should the place be ''boxed in'' by high [[wall]]s or [[hedge]]s. . . | ||

| + | :“Next to the error of rearing high [[fence]]s, is that of bounding the whole premises by a close and connected belt of '''shrubbery''', or other [[plantation]]; leaving the house standing in a small open paddock, unadorned by a plant of any kind; the belt being often separated from it by a deep and broad ditch, or [[ha-ha]].” | ||

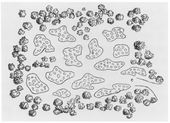

| − | * | + | [[File:1848.jpg|thumb|Fig. 5, [[J. C. Loudon]], Shrubbery formed in the geometric style of gardening, in ''An Encyclopædia of Gardening'', 4th ed. (1826), 804, fig. 557.]] |

| + | *[[J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon|Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius)]], 1826, ''An Encyclopaedia of Gardening'' (1826: 802–4, 806–7, 809)<ref>J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, ''An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening'', 4th ed. (London: Longman et al., 1826), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/KNKTCA4W view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“6130. ''By a '''shrubbery''', or shrub-garden'', we understand a scene for the display of shrubs valued for their beauty or fragrance, combining such trees as are considered chiefly ornamental, and some herbaceous flowers. The form or plan of the ''modern '''shrubbery''''' is generally a winding border, or strip of irregular width, accompanied by a [[walk]], near to which it commences with the herbaceous plants and lowest shrubs, and as it falls back, the shrubs rise in gradation and terminate in the ornamental trees, also similarly graduated. Sometimes a border of '''shrubbery''' accompanies the [[walk]] on both sides; at other times only one side, while the other side is, in some cases, a border for culinary vegetables surrounding the [[kitchen-garden]], but most generally it is an accompanying breadth of turf, varied by occasional groups of trees and plants, or decorations, and with the [[border]], forms what is called [[pleasure-ground]]. | ||

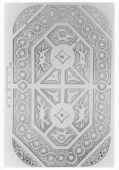

| + | :“6131. ''The sort of '''shrubbery''' formed under the [[geometric style]] of gardening''. . . was more compact; it was called a bosque, [[thicket]] or [[wood]], and contained various compartments of turf or gravel branching from the [[walk]]s, and very generally a [[labyrinth]]. The species of shrubs in those times being very limited, the object was more walks for recreation, shelter, shade, and verdure, than a display of flowering shrubs. . . [Fig. 5] | ||

| + | :“6132. ''In respect to situation'', it is essential that the '''shrubbery''' should commence either immediately at the house, or be joined to it by the [[flower-garden]]; a secondary requisite is, that however far, or in whatever direction it be continued, the [[walk]] be so contrived as to prevent the necessity of going to and returning from the principal points to which it leads over the same ground. . . | ||

| + | :“6138. ''On planting the '''shrubbery''''' the same general remarks, submitted as introductory to ''planting the flower-garden'', are applicable; and shrubs may be arranged in as many different manners as flowers. Trees, however, are permanent and conspicuous objects, and consequently produce an effect during winter, when the greater number of herbaceous plants are scarcely visible. This is more especially the case with that class called evergreens, which, according as they are employed or omitted, produce the greatest difference in the winter aspect of the '''shrubbery'''. We shall here describe four leading modes for the arrangement of the '''shrubbery''', distinguishing them by the names of the mingled or common, the select or grouped manner, and the systematic or methodical style of planting. Before proceeding farther it is requisite to observe, that the proportion of evergreen trees to deciduous trees in cultivation in this country, is as 1 to 12; of evergreen shrubs to deciduous shrubs, exclusive of climbers and creepers but including roses, as 4 to 8; that the time of the flowering of trees and shrubs is from March to August inclusive, and that the colors of the flowers are the same as in herbaceous plants. These data will serve as guides for the selection of species and varieties for the different modes of arrangement, but more especially for the mingled manner. . . | ||

| + | [[File:1353.jpg|thumb|Fig. 6, [[J. C. Loudon]], “The select or grouped manner of planting a shrubbery,” in ''An Encyclopædia of Gardening'', 4th ed. (1826), p. 806, fig. 559.]] | ||

| + | :“6141. ''The select or grouped manner'' of planting a '''shrubbery'''. . . is analogous to the select manner of planting a [[flower-garden]]. Here one genus, species, or even variety, is planted by itself in considerable numbers, so as to produce a powerful effect. Thus the pine tribe, as trees, may be alone planted in one part of the '''shrubbery''', and the holly, in its numerous varieties, as shrubs. After an extent of several yards, or hundreds of yards, have been occupied with these two genera, a third and fourth, say the evergreen fir tribe and the yew, may succeed, being gradually blended with them, and so on. A similar grouping is observed in the herbaceous plants inserted in the front of the [[plantation]]; and the arrangement of the whole as to height, is the same as in the mingled '''shrubbery'''. . . [Fig. 6] | ||

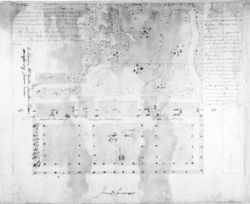

| + | [[File:1847.jpg|thumb|Fig. 7, [[J. C. Loudon]], Ground-plan for “systematic or methodical planting in shrubberies,” in ''An Encyclopædia of Gardening'', 4th ed. (1826), p. 807, fig. 560. The shrubbery is indicated at ''k'' in the upper left quadrant. ]] | ||

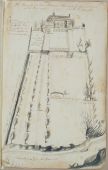

| + | :“6144. ''Systematic or methodical planting in '''shrubberies''''' consists, as in flower-planting, in adopting the Linnaean or Jussieuean arrangement as a foundation, and combining at the same time a due attention to gradation of heights. . . But much the most interesting mode of arrangement would be that of Jussieu, by which a small villa of two or three acres might be raised, as far as gardening is concerned, to the ne plus ultra of interest and beauty. To aid in the formation of such scenes the tables . . . exhibiting the genera contained in each Linnaean or Jussieuean order, and also the number of species distributed according to their places in the garden, will be found of the greatest use. [Fig. 7] | ||

| + | :“6156. ''Decorations in '''shrubberies'''''. Those of the '''shrubbery''' should in general be of a more useful and imposing character than such as are adopted in the [[flower-garden]]. The [[green-house]] and aviary are sometimes introduced, but not, as we think, with propriety, owing to the unsuitableness of the scene for the requisite culture and attention. Open and covered seats are necessary, or, at least, useful decorations, and may occur here and there in the course of the [[walk]], in various styles of decoration, from the rough bench to the [[Rustic_style|rustic]] hut. . . and Grecian [[temple]]. . . Great care, however, must be taken not to crowd these nor any other species of decorations. Buildings being more conspicuous than either [[statue]]s, [[urn]]s, or inscriptions, require to be introduced more sparingly, and with greater caution. In garden or ornamented scenery they should seldom obtrude themselves by their magnitude or glaring color; and rarely be erected but for some obvious purpose of utility. | ||

| + | :“6157. . . Light bowers formed of lattice-work, and covered with climbers, are in general most suitable to parterres; plain covered seats suit the general [[walk]]s of the '''shrubbery'''.” | ||

| − | |||

| + | *[[Noah Webster|Webster, Noah]], 1828, ''An American Dictionary of the English Language'' (1828: 2:n.p.)<ref>Noah Webster, ''An American Dictionary of the English Language'', 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/N7BSU467 view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“'''SHRUB’BERY''', ''n''. Shrubs in general. | ||

| + | :“2. A [[plantation]] of '''shrubs'''.” | ||

| − | |||

| − | : | + | *Teschemacher, James E., May 1, 1835, “On Horticultural Architecture” (''Horticultural Register'' 1: 160–61)<ref>James E. Teschemacher, “On Horticultural Architecture,” ''Horticultural Register, and Gardener’s Magazine'' 1 (May 1, 1835): 157–61, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/ZA92W46U/q/On%20Horticultural%20architecture view on Zotero].</ref> |

| + | :“This [[walk]] might be continued in a serpentine direction on to the vegetable garden behind the house (the entrance to which ought to be concealed by leading round a [[clump]] of thick '''shrubbery'''), first branching off to the [[flower garden]] immediately at the back of the house; which besides roses may be partly devoted to [[bed]]s of tulips, ranunculus, anemone, &c. . . . | ||

| + | :“The entrance on the left will be observed to lead to the stables, partly concealed by trees and '''shrubbery'''; this [[avenue]] also leads to the vegetable garden and would be used for carting manure, coals, wood, &c., the windows of the kitchens facing that way.” | ||

| − | * | + | *Teschemacher, James E., June 1, 1835, “On Horticultural Architecture” (''Horticultural Register'' 1: 229–30)<ref>James E. Teschemacher, “On Horticultural Architecture,” ''Horticultural Register, and Gardener’s Magazine'' 1 (June 1, 1835): 228–30, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/EZCPG4DN/q/On%20Horticultural%20architecture view on Zotero].</ref> |

| + | :“. . . If the '''shrubbery''' constitute the boundary of the premises it would be well to raise the earth at the back about two or three feet higher than the front— at every twenty feet a tree may be planted, such as Catalpa syringifolia, Laburnum, Liriodendron, (tulip tree), Larch, silver leaved Sycamore, purple Beech, Ailanthus, Elegnus, Moose wood, &c. Between these trees place the lofty shrubs, as red and white lilac, dog wood, syringa, smoke tree (Rhus continus), snow ball tree and many others; below these place small shrubs as Symphroia racemosa, varius spireas, particularly spirea bella sorbifolia, laevigata, Rhodora canadensis, swamp honey suckle, (azalea), altheas, mezereon, corchorus, calycanthus, Amorpha fruticosa, Potentilla fruticosa, Tartarean honey suckle, and the common Dutch honey suckle, which if kept low by the knife will be bushy and almost always in flower: in front of these may be placed the low herbaceous flowering plants as, paeonies, red, white and blush, pinks, merocallis, low Phloxes, convallaria majalis (lily of the valley), and other by far to numerous to mention. In planting such a '''shrubbery''' great attention must be paid not to crowd the plants too much, as in a few years they will much impede each other’s growth and altogether destroy the beauty. . . The best finish for the [[border]] of such a '''shrubbery''' is a verge of fine grass not less than eight inches in width, which must be kept frequently mown and neatly edged. At intervals of ten or fifteen feet a tree rose of about five or six feet high is extremely ornamental. If the '''shrubbery''' cross the end of the [[flower garden]], with the [[view]] of concealing the vegetable garden, then trees are not requisite, but simply low shrubs. Three or four years will probably elapse before the '''shrubbery''' will be sufficiently thick for the purpose intended; in the mean time the large gaps between the shrubs which would otherwise have a naked appearance, may be filled with lofty herbaceous and biennial flowers. I know of none more appropriate or beautiful than the red and white foxglove, Solomon’s seal, (Convallaria racemosa, multiflora, latifolia,) Aster, novae angliae and others, Cimicifuga, Helianthus multiflorus, the late phloxes, &c. always supposing these not to be allowed to spread so far as to injure the shrubs. . . | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | *Teschemacher, James E., November 1, 1835, “On Horticultural Architecture” (''Horticultural Register'' 1: 409, 412)<ref>James E. Teschemacher, “On Horticultural Architecture,” ''Horticultural Register, and Gardener’s Magazine'' 1 (November 1, 1835): 409–12, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/EF5F6N9Z/q/On%20Horticultural%20architecture view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“Suppose the area or garden space to be small, one great object would be to shut out by '''shrubbery''' the boundaries, so that the small extent might not appear, to fill every angle and corner with the Lilac or other large and spreading plant, and to take every advantage of the adjoining land. Thus imagine the neighboring piece to be grass; by means of a very open or of a [[sunk fence]] and a grass [[plat]] the grass on both lands would appear to combine and present an extensive expanse of green, or if wood adjoins, then by judicious transplantation an uninterrupted line of [[copse]] would be formed, on which the eye would rest with pleasure. The invisible [[fence]]s commonly used in England, might here be of great service, they are made of thick iron wire, about four feet high, with thin iron posts at distances of eight or ten feet, painted black, so that they form no impediment to such combinations of [[prospect]] with contiguous properties. The same may be done where a rivulet or a piece of water exists near, observing always that such innocent appropriations of our neighbor’s property is much better enjoyed when only caught at glimpses and between intervals of '''shrubbery'''. . . | ||

| + | :“There is also some management necessary in working up such landscapes with an artist’s eye, by opening vistas through [[plantation]]s, concealing barns and outbuildings or [[kitchen garden]]s by judicious management of [[clump]]s of trees, or permitting small glimpses of the [[flower garden]] by gaps in the '''shrubberies'''—an ornamental roof of a greenhouse partly concealed by foliage is an elegant object.” [<span id="Fig_2_cite"></span>[[#Fig_2|See Fig. 2]]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | : | + | *Sayers, Edward, 1838, ''The American Flower Garden Companion'' (1838: 147–49)<ref>Edward Sayers, ''The American Flower Garden Companion, Adapted to the Northern States'' (Boston: Joseph Breck and Company, 1838), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/GHTFN8B2 view on Zotero].</ref> |

| + | :“The '''shrubbery''' is so nearly allied to the [[flower garden]] that in a work professedly treating of the latter, a particular notice of the former subject is required. Indeed, it is rarely that the flower garden has a good and natural appearance without the presence of the '''shrubbery''', either as forming an outline on the margin, or occupying a prominent situation at one end for the convenience of a shady retreat or other useful purpose. . . | ||

| + | :“I recommend that '''shrubbery''' be more frequently planted on the margin of [[lawn]]s, the outsides of the [[flower garden]], and indeed in all kinds of foregrounds and side entrances to residences of almost any denomination. To residences on the main road and in the immediate vicinity of cities, '''shrubbery''' can with every propriety be introduced on the side wings of the [[lawn]] and carriage roads: and in many cases if a belt or [[border]] of some seven or eight feet wide of '''shrubbery''' be planted in front next to the road that passes such places, it would add much to the beauty and value of the property. . . There can be no objection, however, to a few ornamental trees being planted in front of such houses or even mingled with the '''shrubbery''', and particularly if so managed as to form a ''screen or outline'' to protect the building from the cold winds, when trees so situated serve the double purpose of shelter and ornament. | ||

| + | :“In planting shrubs of every denomination, the general rule must be to place the plants so that their habit and appearance will be really ornamental and at the same time subserve (or at least seem to) some useful end: for instance, the taller kinds, as the ''Lilac'', ''Snowball'', and the like, are the most proper to cover board [[fence]]s, and the back part of '''shrubberies'''; the more dwarf kinds, as the ''Double Almond'', ''Roses'', ''Mezeron'' and so on, for the front or facing. There is also some taste required in mixing the varieties of foliage and habits of the different kinds to be planted, which can only be acquired by a due observance of shrubs when in full foliage. The planting should be so managed that when grown up the outline is natural, that is to say, not too formal; but here and there a little broken by some tall shrub growing above the rest. | ||

| + | :“In the front of such plantations a part of the ground should be planted with herbaceous and other kinds of plants, which when nicely mingled with the shrubs form a pretty contrast in the flowering season. Indeed the margin of the '''shrubbery''' is the only situation where such plants will flourish and show to good advantage, besides giving a fine flourish to the whole.” | ||

| − | * | + | *[[Robert Buist|Buist, Robert]], 1841, ''The American Flower Garden Directory'' (1841: 12, 20)<ref>Robert Buist, ''The American Flower Garden Directory'', 2nd ed. (Philadelphia: Carey and Hart, 1841), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/TI7IE55B view on Zotero].</ref> |

| + | :“The outer margin of the [flower] garden should be planted with the largest trees and shrubs: the interior arrangement may be in detached groups of '''shrubbery''' and [[parterre]]s. | ||

| + | :“If '''shrubberies''' were made to a great extent, the scenery would be much more varied and characteristic by grouping judiciously than by indiscriminately planting. | ||

| + | :“However, in small [[flower garden]]s and '''shrubberies''', the latter has to be adopted. In such places, tall growing kinds should never be introduced, unless merely as a screen from some disagreeable object, for they crowd and confuse the whole. The dwarf and more bushy sorts should be placed nearest to the eye, in order that they may conceal the naked stems of the others. Generally when shrubs are planted, they are small; therefore, to have a good effect from the beginning, they should be planted closer than they are intended to stand. When they have grown a few years, and interfere with each other, they can be lifted, and such as have died, or become sickly, replaced, and the remainder can be planted in some other direction. Keep them always distinct, one from another, in order that they may be the better shown off. But, if it is not desired that they should be thicker planted than it is intended to let them remain, the small growing kinds may be six or eight feet apart; the larger, or taller sorts, ten to twenty feet, according to the condition of the soil. | ||

| + | :“Thick masses of '''shrubbery''', called [[thicket]]s, are sometimes wanted. In these there should be plenty of evergreens. A mass of deciduous shrubs has no imposing effect during winter.” | ||

| − | |||

| + | *Barber, John Warner, 1844, describing the village of Roxbury in ''Historical collections, being a general collection of interesting facts, traditions, biographical sketches, anecdotes, &c.'' (1844: 483)<ref>John Warner Barber, ''Historical collections, being a general collection of interesting facts, traditions, biographical sketches, anecdotes, &c., relating to the history and antiquities of every town in Massachusetts, with geographical descriptions'', (1844): 483, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/F53ITP6J view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :"The numerous genteel residences and cottages, which are mostly built on wood and painted white, contrast strongly with the evergreens and '''shrubbery''', by which most of them are surrounded; and during the summer months, the appearance of this place is highly beautiful." | ||

| − | |||

| − | : | + | *Johnson, George William, 1847, ''A Dictionary of Modern Gardening'' (1847: 543)<ref>George William Johnson, ''A Dictionary of Modern Gardening'', ed. David Landreth (Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1847), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/D6PQSNAN view on Zotero].</ref> |

| + | :“'''SHRUBBERY''' is a garden, or portion of a garden, devoted to the cultivation of shrubs. It is not necessary, as Mr. Glenny observes, ‘That there should be any flowers or borders to constitute a '''shrubbery''', but there should be great taste in forming [[clump]]s, and grouping the various foliages and styles of growth. The groundwork in such a garden consists of gravel [[walk]]s and [[lawn]]. If flowers be intermixed, or, which is very generally adopted, there be a space left all round the [[clump]]s to grow flowers in, it becomes a dressed or [[pleasure ground]], rather than a '''shrubbery'''.—Though any part of a ground in which shrubs form the principal feature, is still called a '''shrubbery'''.’— ''Gard. and Prac. Flor''.” | ||

| − | * | + | *[[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing, Andrew Jackson]], April 1847, “Hints on Flower Gardens” (''Horticulturist'' 1: 444)<ref>Andrew Jackson Downing, “Hints on Flower Gardens,” ''Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste'' 1, no. 10 (April 1847): 441–45, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/IRG26IQH view on Zotero].</ref> |

| − | : | + | :". . . still another most delightful scene is reserved, a so-called Rococo garden. . . A garden, laid out in this manner, demands much cleverness and skill in the gardener. . . Around it the most charming landscape open to the [[view]], gently swelling hills, interspersed with pretty village, gardens and grounds. In the plan of the garden, ''a'' and ''b'' are massed of '''shrubs'''; ''c'', circular [[bed]]s, separated by a border or belt of turf, ''e'', from the serpentine [[bed]], ''d''. The whole of this running pattern is surrounded by a border of turf, ''f''; ''g'' and ''h'' are gravel [[walk]]s; i, [[bed]]s, with pedestal and [[statue]] in the centre; ''k'', small oval [[bed]]s, separated from the [[bed]], ''l'', by a border or turf; ''m, n, o, p'', irregular arabesque [[bed]], set in turf." |

| − | + | [[File:0959.jpg|thumb|Fig. 8, Anonymous, “The Shrubbery and Flower Garden,” in ''Cultivator'' 5, no. 4 (April 1848): 114.]] | |

| + | [[File:0771.jpg|thumb|Fig. 9, [[Frances Palmer]], “Ground Plot of Brier Cottage,” in William H. Ranlett, ''The Architect'' (1849), vol. 1, pl. 2.]] | ||

| + | *Thomas, John J., April 1848, “The Shrubbery and Flower Garden” (''Cultivator'' 5: 114)<ref>John J. Thomas, “The Shrubbery and Flower Garden,” ''Cultivator, a Monthly Publication, Devoted to Agriculture'' 5, no. 4 (April 1848): 114–16, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/CRVBXUHR/ view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“With a wish however, to encourage a more graceful, pleasing, and [[picturesque]] mode of laying out even the small [[flower garden]] in connexion with the '''shrubbery''', we have given the above plan, which nearly explains itself.” [Fig. 8] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | *Ranlett, William H., 1849, ''The Architect'' (1849; repr., 1976: 1:5, 33)<ref name="Ranlett">William H. Ranlett, ''The Architect'', 2 vols. (1849–51; repr., New York: Da Capo, 1976), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/QGQPCB5J view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“The [[border]]s [of the proposed cottage grounds, Design I] are filled with a variety of '''shrubbery''', producing a succession of flowers through the season, and a variety of delicate fruit trees are arranged in such order as to ornament the place nearly or quite as much as the standard shrubs, that produce only flowers.” [Fig. 9] | ||

| − | |||

| − | : “The | + | *[[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing, Andrew Jackson]], 1849, ''A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening'' (1849; repr., 1991: 442–45)<ref>A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, ''A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America'', 4th ed. (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1991), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/K7BRCDC5 view on Zotero].</ref> |

| + | :“The '''''shrubbery''''' is so generally situated in the neighborhood of the [[flower-garden]] and the house, that we shall here offer a few remarks on its arrangement and distribution. | ||

| + | :“A collection of flowering shrubs is so ornamental, that to a greater or less extent it is to be found in almost every residence of the most moderate size: the manner in which the shrubs are disposed, must necessarily depend in a great degree upon the size of the grounds, the use or enjoyment to be derived from them, and the prevailing character of the scenery. | ||

| + | :“It is evident, on a moment’s reflection, that shrubs being intrinsically more ornamental than trees, on account of the beauty and abundance of their flowers, they will generally be placed near and about the house, in order that their gay blossoms and fine fragrance may be more constantly enjoyed, than if they were scattered indiscriminately over the grounds. | ||

| + | :“Where a place is limited in size, and the whole lawn and plantations partake of the ''[[pleasure-ground]]'' character, shrubs of all descriptions may be grouped with good effect, in the same manner as trees, throughout the grounds; the finer and rare specics [''sic''] being disposed about the dwelling, and the more hardy and common sorts along the [[walk]]s, and in groups, in different situations near the eye. | ||

| + | :“When, however, the residence is of a larger size, and the grounds have a [[park]]-like extent and character, the introduction of shrubs might interfere with the noble and dignified expression of lofty full grown trees, except perhaps they were planted here and there, among large groups, as ''underwood''. . . When this is the case, however, a portion near the house is divided from the [[park]] (by a wire [[fence]] or some inconspicuous barrier) for [''sic''] the [[pleasure-ground]], where the shrubs are disposed in belts, groups, etc., as in the first case alluded to. | ||

| + | :“There are two methods of grouping shrubs upon lawns which may separately be considered, in combination with ''beautiful'' and ''[[picturesque]]'' scenery. | ||

| + | [[File:0391.jpg|thumb|Fig. 10, Anonymous, “The Irregular Flower-garden,” in [[A. J. Downing]], ''A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening'', 4th ed. (1849), p. 428, fig. 76. This plan shows belts of shrubs arranged in arabesque beds.]] | ||

| + | :“In the first case, where the character of the scene, of the plantations of trees, etc., is that of polished beauty, the belts of shrubs may be arranged similar to herbaceous flowering plants, in arabesque [[bed]]s, along the [[walk]]s. . . In this case, the shrubs alone, arranged with relation to their height, may occupy the beds; or if preferred, shrubs and flowers may be intermingled.” [Fig. 10] | ||

| − | * | + | *New York State Lunatic Asylum Trustees, 1851, describing the ideal grounds for a lunatic asylum (quoted in Hawkins 1991: 53)<ref>Kenneth Hawkins, “The Therapeutic Landscape: Nature, Architecture, and Mind in Nineteenth-Century America” (PhD diss., University of Rochester, 1991), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/UVDGPDHG view on Zotero].</ref> |

| + | :“The salutary influence on the insane mind of highly cultivated [[lawn]]s—pleasant [[walk]]s amid shade trees, '''shrubbery''', and [[fountain]]s, beguiling the long hours of their [''sic''] tedious confinement—giving pleasure, content, and health, by their beauty and variety, are fully appreciated by us.” | ||

| − | |||

| + | *Ranlett, William H., 1851, ''The Architect'' (1851; repr. 1976: 2:39, 78)<ref name="Ranlett"></ref> | ||

| + | :“The windows, the door, and the chimney; the absence of a [[piazza]], the lack of all ornamentation, of vines and '''shrubbery''' [of a house recently erected in the suburbs of NY], bespeak a degree of ignorance of the means of enjoyment, of niggardliness and contracted [[view]]s, that ere long will be looked upon with incredulity. . . | ||

| + | :“City Houses, being seen in long rows, and rarely disconnected from other buildings, do not exhibit their defects so palpably as villas, which stand apart by themselves, and unless particularly concealed by '''shrubbery''', expose their nakedness and defects to all observers.” | ||

| − | |||

| − | : | + | *L., R. B., June 1851, “On Artificial Rockeries” (''Horticulturist'' 6: 279)<ref>R. B. L., “On Artificial Rockeries,” ''Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste'' 6, no. 6 (June 1851): 276–79, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/K4A8SS87/q/on%20artificial%20rockeries view on Zotero].</ref> |

| + | :“It may likewise be observed that rockeries should always be in detached groups, and whether large or small, should never present straight lines or flat surfaces. . . it should always be rather cool, and if possible, shut in by itself by '''shrubbery''', and if possible, also, should be accompanied by a [[jet d’eau]] or [[basin]] of water, or both.” | ||

| − | + | <hr> | |

| − | + | ==Images== | |

| + | ===Inscribed=== | ||

| + | <gallery widths="170px" heights="170px" perrow="7"> | ||

| + | File:0100.jpg|John Trumbull, Plan for Old Brick Rowe, 1793. The three [[square]] privies are surrounded by the '''shrubbery'''. | ||

| − | + | File:0100_detail.jpg|John Trumbull, Plan for Old Brick Rowe [detail], 1793. | |

| − | : | + | File:2249.jpg|Unknown, Derby Garden, [circa 1795–1799], Samuel McIntire Papers, MSS 264, flat file, plan 107. Courtesy of Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum, Rowley, MA. |

| − | + | File:0090.jpg|[[Thomas Jefferson]], Letter describing plans for a “Garden Olitory,” c. 1804. | |

| − | + | File:0166.jpg|[[Thomas Jefferson]], Sketch of the garden and flower [[bed]]s at [[Monticello]], June 7, 1807. “. . . oval [[bed]]s of flowering '''shrubs'''.” | |

| − | |||

| − | + | File:1270.jpg|Solomon Drowne, ''[[Botanic Garden]], 1818'', 1818. “'''Shrubbery'''” is marked in the hemicycle plat. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | File:1221.jpg|[[Robert Mills]], Plan of wings and courtyards, South Carolina Insane Asylum, 1821. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | File:1848.jpg|[[J. C. Loudon]], '''Shrubbery''' formed in the [[geometric style]] of gardening, in ''An Encyclopædia of Gardening'', 4th ed. (1826), 804, fig. 557. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | File:1353.jpg|[[J. C. Loudon]], “The select or grouped manner of planting a '''shrubbery''',” in ''An Encyclopædia of Gardening'', 4th ed. (1826), 806, fig. 559. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | File:1847.jpg|[[J. C. Loudon]], Ground-plan for “systematic or methodical planting in '''shrubberies''',” in ''An Encyclopædia of Gardening'', 4th ed. (1826), 807, fig. 560. The shrubbery is indicated at ''k'' in the upper left quadrant. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | in | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | in the | ||

| − | + | File:1354.jpg|[[J. C. Loudon]], Rough bench in [[Rustic_style|rustic]] hut decorated in '''shrubberies''', in ''An Encyclopædia of Gardening'', 4th ed. (1826), 809, fig. 561. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | File:1355.jpg|[[J. C. Loudon]], “Grecian [[temple]],” in ''An Encyclopaedia of Gardening'' (1826), 809, fig. 562. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [ | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | File:0064.jpg|Anonymous, ''Map of [[Parmentier’s_Horticultural_and_Botanical_Garden|Mr. Andrew Parmentier’s Horticultural & Botanical Garden]], at Brooklyn, Long Island, Two Miles From the City of New York'', c. 1828. | |

| − | |||

| − | [ | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | File:1145.jpg|Anonymous, “Ground Plan of Laurel Hill [[Cemetery/Burying ground/Burial ground|Cemetery]],” in ''Statues of Old Mortality and His Pony, and of Sir Walter Scott'' (1839). "11, '''Shrubbery'''." | |

| − | + | File:0960.jpg|John J. Thomas, “Plan of a Garden,” in ''Cultivator'' 9, no. 1 (January 1842): 22, fig. 8. ". . .rich profusion of '''shrubbery''' near the house. . ." | |

| − | + | File:1503.jpg|Anonymous, "The Rococo Garden of Baron Hügel, near Vienna," Horticulturist, vol. 1, no. 10 (April 1847), pl. opp. p. 441. "''a'' and ''b'' are massed of '''shrubs'''." | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | shrubs | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | File:0959.jpg|Anonymous, “The '''Shrubbery''' and [[Flower_garden|Flower Garden]],” in the ''Cultivator'' 5, no. 4 (April 1848): 114. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | File:0775.jpg|[[Frances Palmer]], Ground [[plot]] of a cottage, in William H. Ranlett, ''The Architect'' (1849), vol. 1, pl. 23. "Ground [[Plot/Plat|plot]]. . . in the [[Modern style/Natural style|natural style]] with [[hedge]] and '''shrub''' [[border]]s." | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | File:1253.jpg|[[Alexander Jackson Davis]], Kirri Cottage for Julia Jackson Davis, 1849. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | File:0777.jpg|[[Frances Palmer]], “Ground [[Plot]] of 4-1/4 Acres,” in William H. Ranlett, ''The Architect'' (1851), vol. 2, pl. 6. "H" marks "a fruit '''shrubbery'''". | |

| − | + | </gallery> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | ===Associated=== | ||

| + | <gallery widths="170px" heights="170px" perrow="7"> | ||

| − | + | File:0056.jpg|[[John Bartram|John]] or [[William Bartram]], "A Draught of [[Bartram_Botanic_Garden_and_Nursery|John Bartram’s House and Garden]] as it appears from the River", 1758. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | or | ||

| − | of | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | File:0069.jpg|[[Samuel Vaughan]], Plan of [[Mount Vernon]], 1787. | |