Difference between revisions of "Basin"

(→Usage) |

V-Federici (talk | contribs) m |

||

| (123 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | (Bason) <br/> | ||

| + | See also: [[Canal]], [[Fountain]] | ||

| + | |||

==History== | ==History== | ||

| − | + | [[File:0496.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 1, [[Charles Fraser]], ''A '''Bason''' and Storehouse Belonging to the Santee [[Canal]]'', 1803.]] | |

| − | in American landscape design vocabulary: as | + | |

| − | a part of a waterway and as a receptacle of | + | [[File:0460.jpg|thumb|Fig.2, Charles Varlé, ''Project for the Improvement of the [[Square]] and the Town of Bath'', 1809.]] |

| − | water. As part of a waterway, the term | + | |

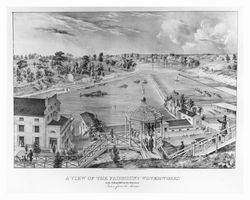

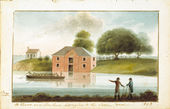

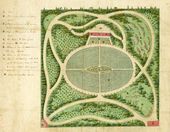

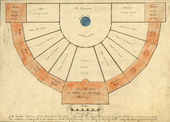

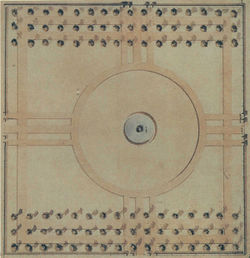

| − | referred to a protected area of a river or sea | + | The term basin had at least two applications in American landscape design vocabulary: as a part of a waterway and as a receptacle of water. As part of a waterway, the term referred to a protected area of a river or sea or a widening in a [[canal]] where boats, such as those in [[Charles Fraser|Charles Fraser's]] painting of the basin on the Santee [[Canal]] in South Carolina [Fig. 1], were moored, repaired, loaded, and unloaded. While basins on navigable canals were rarely landscaped, they were occasionally incorporated into public landscape designs, such as those at Fairmount Waterworks in Philadelphia and at the [[national Mall]] in Washington, DC. A [[canal]] and basin were created expressly for a public garden in Charles Varlé’s plan for the town of Bath, which included a [[jet|''jet d’eau'']] in the center of the rectangular basin [Fig. 2]. In the second application of the term, “basin” described a receptacle of water issued from a spring (the garden of Charles Wistar in Philadelphia), a stream (Mr. V.’s residence in [[Hallowell, Maine]], as described by [[Timothy Dwight]]), underground pipes ([[Charles Willson Peale|Charles Willson Peale's]] estate, [[Belfield]]), or a [[fountain]] (W. H. Corcoran’s garden in Washington, DC, as described by C. M. Hovey). Both meanings of the term appear to have been consistent throughout the period under study, and the frequency of associating basins with fountains likely increased with the introduction of pressurized water systems.<span id="Loudon_cite"></span> |

| − | or a widening in a canal where boats, such as | + | |

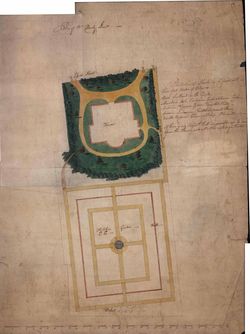

| − | those in Charles | + | [[File:2249.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 3,Unknown, Derby Garden, circa 1795–1799.]] |

| − | on the Santee Canal in South Carolina [Fig. 1], | + | Two treatises identified construction materials for basins. [[J. C. Loudon]] (1826) noted that large garden basins may be formed of clay-lined excavations or lined with pavement, tiles, or lead ([[#Loudon|view text]]), and <span id="JaneLoudon_cite"></span>[[Jane Loudon]] (1845) recommended that “all geometrical or architectural basins of water ought to have margins of masonry” ([[#Loudon|view text]]). <span id="Peale_cite"></span>It is difficult to determine whether most garden basins were built according to such treatise advice, but two examples specify other materials.<span id="Trollope_cite"></span> In 1814, [[Charles Willson Peale]] described having his basin at [[Belfield]] “walled up with a proper mortar” ([[#Peale|view text]]), and in another letter mentioned a marble basin. Frances Trollope in 1830 described the stone basin at Fairmount Waterworks complete with a cup “for the service of the thirsty traveller” ([[#Trollope|view text]]). |

| − | were moored, repaired, loaded, and unloaded. | + | |

| − | While basins on navigable canals were rarely | + | [[File:0063.jpg|thumb|Fig. 4, [[Benjamin Henry Latrobe]], “Plan of the public [[Square]] in the city of New Orleans, as proposed to be improved. . .” [detail], March 20, 1819.]] |

| − | landscaped, they were occasionally incorporated | + | The visual and textual evidence for basins suggests that they were located in a variety of contexts in garden plans. Inscribed images of basins are relatively rare, but the drawing by an unknown artist for the layout of the Elias Hasket Derby Farm in Peabody, Massachusetts [Fig. 3], depicts a basin in the center of the plan for a [[kitchen garden]]. Although the Derby garden is curiously off-axis with the house, the basin is the central feature of the garden, and marks the intersection of the [[walk]]s. Other unlabelled paintings and plans depict similar circular, centrally placed water receptacles, which are most likely to be interpreted as basins. For example, [[Benjamin Henry Latrobe|Benjamin Henry Latrobe's]] plan of 1819 for the Place d’Armes (renamed Jackson Square) in New Orleans [Fig. 4], and the painting of Col. George Boyd’s [[seat]] in Portsmouth, New Hampshire [Fig. 5], both include central basins. In other instances, basins were placed in [[rockery|rockeries]] or in locations determined by water sources such as springs and streams. |

| − | into public landscape designs, such as | ||

| − | those at Fairmount Waterworks in Philadelphia | ||

| − | and at the national Mall in Washington, | ||

| − | + | [[File:2262.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 5, Anonymous, ''The South West [[Prospect]] of the [[Seat]] of Colonel George Boyd of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, New England, 1774''.]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[File:0594.jpg|thumb|Fig. 6, [[Benjamin Henry Latrobe]], Section of the northern course of the [[canal]] from the tide in the Elk River at Frenchtown to the forked [oak] in Mr. Rudulph’s swamp, 1803.]] | |

| − | + | <span id="Forsyth_cite"></span> | |

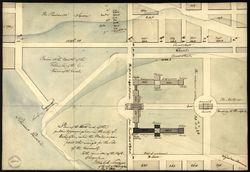

| − | + | As treatises suggested, basins of water not only cooled and animated the garden but, as William Forsyth (1802) noted, they also provided the practical functions of drainage and rain collection ([[#Forsyth|view text]]). [[Charles Willson Peale|Peale]] used basins as water collection points for his hydraulic system, and [[Robert Mills|Robert Mills's]] plan for the [[national Mall]], Washington, DC, called for water from [[fountain]]s to be collected in basins and transported through underground pipes for irrigating the public garden. Landscape design on an urban scale often required the redirection and creation of alternative waterways. Drawings by [[Benjamin Henry Latrobe|Latrobe]] for the creation of a national university on the [[national Mall|Mall]] [<span id="Fig_8_cite"></span>[[#Fig_8|See Fig. 8]]] and for the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal [Fig. 6] indicated that basins were key elements in his designs. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | the | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | basins. | ||

| − | |||

| − | [Fig. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | basins were | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | —''Elizabeth Kryder-Reid'' | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | <hr> | |

==Texts== | ==Texts== | ||

| + | ===Usage=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | *[[Eliza Lucas Pinckney|Pinckney, Eliza Lucas]], c. May 1743, in a letter to Miss Bartlett, describing Crowfield, plantation of William Middleton, vicinity of Charleston, SC (1972: 61)<ref>Eliza Lucas Pinckney, ''The Letterbook of Eliza Lucas Pinckney, 1739–1762'', ed. Elise Pinckney (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1972), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/EBQQ2RAU view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | :“. . . as you draw nearer [the house] new beauties discover themselves, first the fruitful Vine manteling up the wall loading with delicious Clusters; next a spacious '''bason''' in the midst of a large [[green]] presents itself as you enter the [[gate]] that leads to the house.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | *Anonymous, January 30, 1749, describing a plantation for sale near Charleston, SC (''South Carolina Gazette'') | ||

| + | |||

| + | :“TO BE SOLD at Public Vendue. . . his [[plantation]]s on the ''Ashley-River'' and ''Wappoo-Creek''. . . [with] a very large garden both for pleasure and profit, with variety of pleasant [[walk]]s, [[mount]]s, '''basons''', [[canal]]s.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | *[[Timothy Dwight|Dwight, Timothy]], 1796, describing the residence of Mr. V., [[Hallowell, ME]] (1821: 2:219)<ref>Timothy Dwight, ''Travels in New-England and New-York'', 4 vols. (New Haven, CT: T. Dwight, 1821), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/KHT2AUCG view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | :“Behind the garden is a wild and solitary valley; at the bottom of which runs a small mill stream. Its bed is formed, universally, of rocks and stones. In three successive instances strata of rocks cross the stream obliquely; and present a face so nearly perpendicular, as to furnish in each instance, a charming [[cascade]]. These succeed each other at distances conveniently near; and yet so great, that one of them only can be seen at a time. The remaining course of the stream is an alternation of currents, and handsome '''basins'''.” | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | * Scott, Joseph, 1806, describing Fairmount Waterworks, Philadelphia, PA (1806: 25)<ref>Joseph Scott, ''A Geographical Description of Pennsylvania'' (Philadelphia: Printed by R. Cochran, 1806), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/55XKIWPN view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“The water-works of Philadelphia are the most extensive of their kind of any in America. They consist of a '''basin''', excavated, partly in the bed of the river Schuylkill, three feet deeper than low-water mark. The '''basin''' is protected in front, towards the river, by a solid wall of wrought granite, 72 feet long and 16 thick. It is founded upon the rock, which forms the bed of the river, and is raised 16 feet above high-water mark, so as to secure it against every fresh. In the centre of this wall is a sluice, which admits or excludes, at pleasure, the water of the '''basin'''. The '''basin''' extends easterly to high-water mark, where it is secured by another wall and sluice, admitting the water to a [[canal]] 40 feet wide, and 200 feet long.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | the | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *[[Charles Willson Peale|Peale, Charles Willson]], July 22, 1810, in a letter to his son, Rembrandt Peale, describing the garden of Charles Wistar, Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Rudnytzky 1986: 40)<ref>Kateryna A. Rudnytzky, “The Union of Landscape and Art: Peale’s Garden at Belfield” (Honors thesis, LaSalle University, 1986), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/KJK46QBZ view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“There is a Spring belonging to Chas Wistar in the most romantic scinery [''sic]'' your imagination can conceive. . . The spring comes out a large rock into a '''bason''' which is covered with another large rock, then passes beneath a rock under your feet, and bursts out again before it joins the creek.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[File:0044_detail3.jpg|thumb|Fig. 7, [[Charles Willson Peale]], ''[[View]] of the garden at [[Belfield]]'' [detail], 1816.]] | |

| − | + | * <div id="Peale"></div>[[Charles Willson Peale|Peale, Charles Willson]], 1814, describing [[Belfield]], estate of Charles Willson Peale, Germantown, PA (Miller et al., eds., 1991: 3:239, 266)<ref>Lillian B. Miller et al., eds., ''The Selected Papers of Charles Willson Peale and His Family,'' vol. 3, ''The Belfield Farm Years, 1810–1820'' (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1991), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/IZAKPCBG view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“[15, 27, 29 March] As soon as the weather becomes settled & warm, I will have the '''Bason''' walled up with a proper morter, and when that is doing I shall put a Cock to the Leaden pipe to let the water pass out untill the '''Bason''' is prepaired to receive it. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | the | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“[14 September] . . . The fountain '''Bason''' now holds water completly, and the [[jet]] is 12 feet high, and is kept continually playing; Day & night, Rubens has placed all his plants round the '''Bason''', and it is very handsome.” [Fig. 7] [[#Peale_cite|back up to History]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | <div id="Fig_8"></div>[[File:0414.jpg|thumb|Fig. 8, [[Benjamin Henry Latrobe]], Plan of the west end of the public appropriation in the city of Washington, called the [[National Mall|Mall]]: as proposed to be arranged for the site of the university, 1816. [[#Fig_8_cite|back up to History]]]] | |

| − | + | *[[Benjamin Henry Latrobe|Latrobe, Benjamin Henry]], 1816, describing his drawing for the creation of a national university on the Mall (Library of Congress) | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | “ | + | :“'''Basin''' at the mouth of the Tiber, being the entrance of the [[Canal]].” [Fig. 8] |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | the | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *[[Charles Willson Peale|Peale, Charles Willson]], c. 1825, describing [[Belfield]], estate of Charles Willson Peale, Germantown, PA (Miller et al., eds., 2000: 5:383)<ref>Lillian B. Miller et al., eds., ''The Selected Papers of Charles Willson Peale and His Family,'' vol. 5, ''The Autobiography of Charles Willson Peale'' (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/IZAKPCBG view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“. . . below the [[greenhouse|Green house]] he made a round '''bason''' to receive the Water from the cave back of it—and from the fish-[[pond]] near the spring-house, to this '''bason''' in the Garden is a fall of 15 feet, and in order to have a [[fountain]] in the '''Bason''' he put log-pipes under ground, and thus had a [[jet]] of 13 feet high but of small diameter, in order that it might constantly [be] rising. but unfortunately he make the bore of his logs only of one inch diameter, the consequence was that Frogs in two instances got into the bore of the logs and not being able to pass through all the joints, stopped the water, of course to free the passage of the logs, gave much labour. had these things been foreseen, trouble might have been prevented, by making the bore of the logs of a greater diameter, with other provisions to keep the passage free.” | |

| − | in the | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[File:0541.jpg|thumb|Fig. 9, John T. Bowen, ''A [[View]] of Fairmount Water-Works with Schuylkill in the distance, taken from the [[Mount]]'', 1838.]] | |

| − | + | *<div id="Trollope"></div>Trollope, Frances Milton, 1830, describing Fairmount Waterworks, Philadelphia, PA (1832: 2:43–44)<ref>Frances Trollope, ''Domestic Manners of the Americans'', 3rd ed., 2 vols. (London: Wittaker, Treacher, 1832), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/T5RXDF7G/ view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“[Fair Mount] is, in truth, one of the prettiest spots the eye can look upon. A broad wear is thrown across the river Schuylkill, which produces the sound and look of a [[cascade]]. On the farther side of the river is a gentleman’s [[seat]], the beautiful [[lawn]]s of which slope to the water’s edge, and groups of weeping-willows and other trees throw their shadows on the stream. The works themselves are enclosed in a simple but very handsome building of freestone, which has an extended front opening upon a [[terrace]], which overhangs the river: behind the building, and divided from it only by a [[lawn]], rises a lofty [[wall]] of solid lime-stone rock, which has, at one or two points, been cut into, for the passage of the water into the noble reservoir above. From the crevices of this rock the catalpa was every where pushing forth, covered with its beautiful blossom. Beneath one of these trees an artificial opening in the rock gives passage to a stream of water, clear and bright as crystal, which is received in a stone '''basin''' of simple workmanship, having a cup for the service of the thirsty traveller.” [Fig. 9] [[#Trollope_cite|back up to History]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | the | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[File:0034.jpg|thumb|Fig. 10, [[Robert Mills]], Alternative plan for the grounds of the National Institution, 1841.]] | |

| + | *[[Robert Mills|Mills, Robert]], February 23?, 1841, in a letter to Joel R. Poinsett, describing his design for the [[National Mall]], Washington, DC (Scott, ed., 1990: n.p.)<ref>Pamela Scott, ed., ''The Papers of Robert Mills'' (Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Resources, 1990), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/9CEBJWW8 view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“The main building for the Institution is located about 300 feet south of the [[wall]] fronting the [[Botanic garden]], from which it is separated by a circular road, in the centre of which is a [[fountain]] of water from the '''basin''' of which pipes are led underground thro’ the [[walk]]s of the garden, for irrigating the same at pleasure, the [[fountain]]s may be supplied from the [[canal]] flowing near the north [[wall]] of inclosure.” [Fig. 10] | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), October 1845, “Notes of a Visit to several Gardens in the Vicinity of Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York,” describing the garden of W. H. Corcoran, Washington, DC (''Magazine of Horticulture'' 12: 245)<ref>Charles Mason Hovey, “Notes of a Visit to several Gardens in the Vicinity of Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York, in October, 1845,” ''Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and all useful discoveries and improvements in Rural Affairs'' 12, no. 7 (July 1846): 241–48, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/S9UVTJM3 view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“At one end of the garden, is a very neatly constructed [[rockwork|rock work]], with a '''basin''' in the centre, supplied with water from a cistern placed at some distance, but which is only a few feet higher than the water. Small tubes project through the [[rockwork|rock work]], and by turning a cock, the water is thrown up in several small [[jet]]s and falls into the '''basin'''. Such [[fountain]]s are constructed at very little expense, and in small gardens they afford much gratification.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | a | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *[[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing, Andrew Jackson]], 1851, describing plans for improving the public grounds in Washington, DC (quoted in Washburn 1967: 55)<ref>Wilcomb E. Washburn, “Vision of Life for the Mall,” ''AIA Journal'' 47 (1967): 52–59, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/TA59MHC7/ view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“5th: [[Fountain]] Park | |

| − | the | + | :“This Park would be chiefly remarkable for its water features. The [[Fountain]] would be supplied from a '''basin''' in the Capitol. The pond or lake might either be formed from the overflow of this [[fountain]], or from a filtering drain from the [[canal]].” |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Citations=== | ===Citations=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Langley, Batty, 1728, ''New Principles of Gardening'' (1728; repr., 1982: 195–202)<ref>Batty Langley, ''New Principles of Gardening, or The Laying out and Planting Parterres, Groves, Wildernesses, Labyrinths, Avenues, Parks, &c.'' (1728; repr. New York and London: Garland Publishing, 1982), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/MRDTAEKC view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | :“''General'' DIRECTIONS, ''&c.'' . . . | ||

| + | |||

| + | :“XVIII. That the Intersections of [[Walk]]s be adorn’d with [[Statue]]s, large open Plains, [[Grove]]s, Cones of Fruit, of Ever-Greens, of Flowering Shrubs, of Forest Trees, '''Basons''', [[Fountain]]s, [[sundial|Sun-Dials]], and [[Obelisk]]s. . . | ||

| + | |||

| + | :“XXXIV. Where Water is easy to be had, always introduce a '''Basin''' or [[Fountain]] in every [[flower garden|Flower]] and Fruit-Garden, [[Grove]], and other pleasing Ornaments, in the several private Parts of your rural Garden.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | *[[Ephraim Chambers|Chambers, Ephraim]], 1741, ''Cyclopaedia'' (1741: 1:n.p.)<ref>Ephraim Chambers, ''Cyclopaedia, or An Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences. . . '', 5th ed., 2 vols. (London: D. Midwinter et al., 1741–43), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/PTXK378N view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | :“'''BASON''' is also used on various occasions for a small reservatory of water: as the '''''bason''''' of a [[jet|jet d’eau]], or [[fountain]]; the '''''bason''''' of a port, of a bath, ''&c''. which last Vitruvius calls ''labrum''. See [[Fountain|FOUNTAIN]].” | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | *Johnson, Samuel, 1755, ''A Dictionary of the English Language'' (1755: 1:n.p.)<ref>Samuel Johnson, ''A Dictionary of the English Language: In Which the Words Are Deduced from the Originals and Illustrated in the Different Significations by Examples from the Best Writers'', 2 vols. (London: W. Strahan for J. and P. Knapton, 1755), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/GE2JPJR3 view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | :“'''BASIN'''. ''n.s.'' [''basun'', Fr. ''bacile'', ''bacino'', Ital. It is often written ''bason'', but not according to etymology.] | ||

| + | |||

| + | :“1. A small vessel to hold water for washing, or other uses. . . | ||

| + | |||

| + | :“2. A small [[pond]]. . . | ||

| + | |||

| + | :“5. A dock for repairing and building ships.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | *<div id="Forsyth"></div>Forsyth, William, 1802, ''A Treatise on the Culture and Management of Fruit Trees'' (1802: 147),<ref>William Forsyth, ''A Treatise on the Culture and Management of Fruit Trees'' (Philadelphia: J. Morgan, 1802), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/ZSNDFTE9 view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | :“Gardens, if possible, should lie near a river, or brook, that they may be well supplied with water. . . | ||

| + | |||

| + | :“If the ground be wet and spewy, it will be proper to make a '''bason''' in the most convenient place, to receive the water that comes from the drains, and to collect the rain that falls on the [[walk]]s.” [[#Forsyth_cite|back up to History]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:1321.jpg|thumb|Fig. 11, [[J. C. Loudon]], “[[Pond]]s or large '''basins'''" and “Tanks or cisterns,” in ''An Encyclopædia of Gardening'' (1826), 339, figs. 286–88.]] | ||

| + | [[File:1368.jpg|thumb|Fig. 12, [[J. C. Loudon]], A garden in the [[Ancient_style|ancient style]], in ''An Encyclopædia of Gardening'' (1826), p. 1009, fig. 694.]] | ||

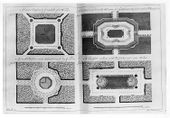

| + | *<div id="Loudon"></div>[[J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon|Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius)]], 1826, ''An Encyclopaedia of Gardening'' (1826: 339, 1009)<ref>J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, ''An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening'', 4th ed. (London: Longman et al., 1826), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/KNKTCA4W view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | :“1718. ''Reservoirs'' may be either tanks, cisterns, '''basins''', or [[pond]]s. . . | ||

| + | |||

| + | :“1719. ''[[Pond]]s or large '''basins'''''. . . are reservoirs formed in excavations, either in soils retentive of water, or rendered so by the use of clay. . . Sometimes these '''basins''' are lined with pavement, tiles, or even lead, and the last material is the best, where complete dryness is an object around the margin. . . [Fig. 11] | ||

| + | |||

| + | :“7216. ''Water''. . .forms a part of every garden in the [[ancient style]], in the various artificial characters which it there assumes of oblong [[canal]]s, [[pond]]s, '''basins''', [[cascade]]s, and ''[[jet|jets d’eaux]]''. . .” [Fig. 12] [[#Loudon_cite|back up to History]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | *[[Noah Webster|Webster, Noah]], 1828, ''An American Dictionary of the English Language'' (1828: 2:n.p.)<ref>Noah Webster, ''An American Dictionary of the English Language'', 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/N7BSU467/ view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | :“'''BAS'IN''', n. ''básn''. [Fr. ''bassin''; Ir. ''baisin''; Arm. ''baçzin''; It. ''bacino'', or ''bacile''; Port. ''bacia''. . .] | ||

| + | |||

| + | :“1. A hollow vessel or dish, to hold water for washing, and for various other uses. | ||

| + | |||

| + | :“2. In ''hydraulics'', any reservoir of water. | ||

| + | |||

| + | :“3. That which resembles a '''basin''' in containing water, as a [[pond]], a dock for ships, a hollow place for liquids, or an inclosed part of water, forming a broad space within a strait or narrow entrance; a little bay.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:0402.jpg|thumb|Fig. 13, Anonymous, "A simple jet. . . the simplest and most pleasing of fountains," in [[A. J. Downing]], ''A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening'' (1849), p. 471, fig. 92.]] | ||

| + | *<div id="JaneLoudon"></div>[[Loudon, Jane]], 1845, ''Gardening for Ladies'' (1845: 413)<ref>Jane Loudon, ''Gardening for Ladies; and Companion to the Flower-Garden'', ed. [[A. J. Downing]] (New York: Wiley & Putnam, 1845), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/3Q5GCH4I/ view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | :“Water as an element of landscape scenery, is exhibited in small gardens either in ponds or '''basins''', of regular geometrical or architectural forms; or in [[pond]]s or small [[lake]]s of irregular forms in imitation of the shapes seen in natural landscape. In general all geometrical or architectural '''basins''' of water ought to have the margins of masonry, or at least of stones placed so as to imitate a rocky margin. The reason is, that by these means the artificial character is heightened, and also a colour is introduced between the surrounding grass, vegetation, gravel, or dug-ground, which harmonizes the water with the land. Artificial shapes of this kind should never be of great diameter, because in that case the artificial character is comparatively lost, and the idea of nature occurs to the spectator.” [[#JaneLoudon_cite|back up to History]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | *[[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing, Andrew Jackson]], 1849, ''A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening'' (1849: 471)<ref>A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, ''A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America'', 4th ed. (1849; repr., Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1991), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/K7BRCDC5 view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | :“A simple [[jet]]. . . issuing from a circular '''basin''' of water, or a cluster of perpendicular [[jet]]s (candelabra [[jet]]s), is at once the simplest and most pleasing of [[fountain]]s. Such are almost the only kinds of [[fountain]]s which can be introduced with propriety in simple scenes where the predominant objects are sylvan, not architectural.” [Fig. 13] | ||

| + | |||

| + | <hr> | ||

==Images== | ==Images== | ||

| + | ===Inscribed=== | ||

| + | <span id="roundabout_img"></span> | ||

| + | <gallery widths="170px" heights="170px" perrow="7"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:1055.jpg|Michael van der Gucht, “Four Designs for Cloisters,” in A.-J. Dézallier d’Argenville, ''The Theory and Practice of Gardening'' (1712), pl. 9. Fig. 2nd, on the bottom left, has “an eight corner’d '''Bason'''.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:1385.jpg|Batty Langley, “Design of a Small Garden Situated in a Park,” in ''New Principles of Gardening'' (1728), pl. XII. “. . . the House to the ''North'' opens upon a ''noble circular '''Basin''' of Water'' B. . .” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:1053.jpg|Batty Langley, “Design of a ''rural Garden'', after the new manner,” in ''New Principles of Gardening'' (1728), pl. III. “In the Center of this [[Parterre]] is an octagon '''Basin''' of Water. . .” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:2249.jpg|Unknown, Derby Garden, [circa 1795–1799], Samuel McIntire Papers, MSS 264, flat file, plan 107. Courtesy of Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum, Rowley, MA. The small circle in the middle of the [[Kitchen Garden]] is marked '''Bason'''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0496.jpg|[[Charles Fraser]], ''A '''Bason''' and Storehouse Belonging to the Santee Canal'', 1803. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0594.jpg|[[Benjamin Henry Latrobe]], Section of the northern course of the [[canal]] from the tide in the Elk River at Frenchtown to the forked [oak] in Mr. Rudulph’s swamp, 1803. The '''Basin''' is between the [[canal]] and the Elk River. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:2259.jpg|Anonymous, Plan of the Harvard [[Botanic Garden]], c. 1807. “C. '''Bason''' or reservoir with running & fragrant waters.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0460.jpg|Charles Varlé, ''Project for the Improvement of the Square and the Town of Bath'', 1809. “B” marks “'''Bason'''” on the right of the plan. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0414.jpg|[[Benjamin Henry Latrobe]], Plan of the west end of the public appropriation in the city of Washington, called the [[National Mall|Mall]]: as proposed to be arranged for the site of the university, 1816. “'''Basin''' at the mouth of the Tiber, being the entrance of the [[Canal]].” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:1221.jpg|[[Robert Mills]], Plan of wings and courtyards, South Carolina Insane Asylum, 1821. “[[Fountain]] '''basin'''.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:1321.jpg|[[J. C. Loudon]], “[[Pond]]s or large '''basins'''” and “Tanks or cisterns,” in ''An Encyclopædia of Gardening'' (1826), 339, figs. 286–88. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:1368.jpg|[[J. C. Loudon]], A garden in the [[Ancient_style|ancient style]], in ''An Encyclopædia of Gardening'' (1826), 1009, fig. 694. “[Water] forms a part of every garden in the [[Ancient_style|ancient style]], in the various artificial characters which it there assumes. . . '''basins'''. . .” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0433.jpg|[[Robert Mills]], “Plan of the Washington [[Canal]],” 1831. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0540.jpg|John Caspar Wild, ''Fairmount Waterworks'', 1838. “There are six '''basins''' (a bird’s eye [[view]] of which is shown in the vignette).” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0402.jpg|Anonymous, "A simple [[jet]]. . . the simplest and most pleasing of [[fountain]]s," in [[A. J. Downing]], ''A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening'' (1849), 471, fig. 92. “A simple [[jet]]. . . issuing from a circular '''basin''' of water. . .” | ||

| + | |||

| + | </gallery> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Associated=== | ||

| + | <gallery widths="170px" heights="170px" perrow="7"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0044.jpg|[[Charles Willson Peale]], ''[[View]] of the garden at [[Belfield]]'', 1816. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0541.jpg|John T. Bowen, ''A [[View]] of the Fairmount Water-Works with Schuylkill in the distance, taken from the [[Mount]]'', 1838. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0034.jpg|[[Robert Mills]], Alternative plan for the grounds of the National Institution, 1841. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0459.jpg|Jenny Emily Snow, attr., ''Fairmount Park Waterworks'', c. 1850. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </gallery> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Attributed=== | ||

| + | <gallery widths="170px" heights="170px" perrow="7"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:2262.jpg|Anonymous, ''The South West [[Prospect]] of the [[Seat]] of Colonel George Boyd of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, New England, 1774''. | ||

| − | + | Image:0258.jpg|William Clarke, ''Mrs. Levin Winder'' (Mary Stoughton Sloss), 1793. | |

| + | |||

| + | Image:0063.jpg|[[Benjamin Henry Latrobe]], “Plan of the public [[Square]] in the city of New Orleans, as proposed to be improved. . .” [detail], March 20, 1819. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0006.jpg|Harriet De (?), ''The Duck [[Pond]]'', c. 1820. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:1173.jpg|Anonymous, The Diploma for the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, c. 1836, in ''Yearbook of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society'' (1956), frontispiece. | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <hr> | ||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| Line 292: | Line 234: | ||

[[Category:Keywords]] | [[Category:Keywords]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Water Features]] | ||

Latest revision as of 15:51, April 8, 2021

(Bason)

See also: Canal, Fountain

History

The term basin had at least two applications in American landscape design vocabulary: as a part of a waterway and as a receptacle of water. As part of a waterway, the term referred to a protected area of a river or sea or a widening in a canal where boats, such as those in Charles Fraser's painting of the basin on the Santee Canal in South Carolina [Fig. 1], were moored, repaired, loaded, and unloaded. While basins on navigable canals were rarely landscaped, they were occasionally incorporated into public landscape designs, such as those at Fairmount Waterworks in Philadelphia and at the national Mall in Washington, DC. A canal and basin were created expressly for a public garden in Charles Varlé’s plan for the town of Bath, which included a jet d’eau in the center of the rectangular basin [Fig. 2]. In the second application of the term, “basin” described a receptacle of water issued from a spring (the garden of Charles Wistar in Philadelphia), a stream (Mr. V.’s residence in Hallowell, Maine, as described by Timothy Dwight), underground pipes (Charles Willson Peale's estate, Belfield), or a fountain (W. H. Corcoran’s garden in Washington, DC, as described by C. M. Hovey). Both meanings of the term appear to have been consistent throughout the period under study, and the frequency of associating basins with fountains likely increased with the introduction of pressurized water systems.

Two treatises identified construction materials for basins. J. C. Loudon (1826) noted that large garden basins may be formed of clay-lined excavations or lined with pavement, tiles, or lead (view text), and Jane Loudon (1845) recommended that “all geometrical or architectural basins of water ought to have margins of masonry” (view text). It is difficult to determine whether most garden basins were built according to such treatise advice, but two examples specify other materials. In 1814, Charles Willson Peale described having his basin at Belfield “walled up with a proper mortar” (view text), and in another letter mentioned a marble basin. Frances Trollope in 1830 described the stone basin at Fairmount Waterworks complete with a cup “for the service of the thirsty traveller” ().

The visual and textual evidence for basins suggests that they were located in a variety of contexts in garden plans. Inscribed images of basins are relatively rare, but the drawing by an unknown artist for the layout of the Elias Hasket Derby Farm in Peabody, Massachusetts [Fig. 3], depicts a basin in the center of the plan for a kitchen garden. Although the Derby garden is curiously off-axis with the house, the basin is the central feature of the garden, and marks the intersection of the walks. Other unlabelled paintings and plans depict similar circular, centrally placed water receptacles, which are most likely to be interpreted as basins. For example, Benjamin Henry Latrobe's plan of 1819 for the Place d’Armes (renamed Jackson Square) in New Orleans [Fig. 4], and the painting of Col. George Boyd’s seat in Portsmouth, New Hampshire [Fig. 5], both include central basins. In other instances, basins were placed in rockeries or in locations determined by water sources such as springs and streams.

As treatises suggested, basins of water not only cooled and animated the garden but, as William Forsyth (1802) noted, they also provided the practical functions of drainage and rain collection (view text). Peale used basins as water collection points for his hydraulic system, and Robert Mills's plan for the national Mall, Washington, DC, called for water from fountains to be collected in basins and transported through underground pipes for irrigating the public garden. Landscape design on an urban scale often required the redirection and creation of alternative waterways. Drawings by Latrobe for the creation of a national university on the Mall [See Fig. 8] and for the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal [Fig. 6] indicated that basins were key elements in his designs.

—Elizabeth Kryder-Reid

Texts

Usage

- Pinckney, Eliza Lucas, c. May 1743, in a letter to Miss Bartlett, describing Crowfield, plantation of William Middleton, vicinity of Charleston, SC (1972: 61)[1]

- “. . . as you draw nearer [the house] new beauties discover themselves, first the fruitful Vine manteling up the wall loading with delicious Clusters; next a spacious bason in the midst of a large green presents itself as you enter the gate that leads to the house.”

- Anonymous, January 30, 1749, describing a plantation for sale near Charleston, SC (South Carolina Gazette)

- “TO BE SOLD at Public Vendue. . . his plantations on the Ashley-River and Wappoo-Creek. . . [with] a very large garden both for pleasure and profit, with variety of pleasant walks, mounts, basons, canals.”

- Dwight, Timothy, 1796, describing the residence of Mr. V., Hallowell, ME (1821: 2:219)[2]

- “Behind the garden is a wild and solitary valley; at the bottom of which runs a small mill stream. Its bed is formed, universally, of rocks and stones. In three successive instances strata of rocks cross the stream obliquely; and present a face so nearly perpendicular, as to furnish in each instance, a charming cascade. These succeed each other at distances conveniently near; and yet so great, that one of them only can be seen at a time. The remaining course of the stream is an alternation of currents, and handsome basins.”

- Scott, Joseph, 1806, describing Fairmount Waterworks, Philadelphia, PA (1806: 25)[3]

- “The water-works of Philadelphia are the most extensive of their kind of any in America. They consist of a basin, excavated, partly in the bed of the river Schuylkill, three feet deeper than low-water mark. The basin is protected in front, towards the river, by a solid wall of wrought granite, 72 feet long and 16 thick. It is founded upon the rock, which forms the bed of the river, and is raised 16 feet above high-water mark, so as to secure it against every fresh. In the centre of this wall is a sluice, which admits or excludes, at pleasure, the water of the basin. The basin extends easterly to high-water mark, where it is secured by another wall and sluice, admitting the water to a canal 40 feet wide, and 200 feet long.”

- Peale, Charles Willson, July 22, 1810, in a letter to his son, Rembrandt Peale, describing the garden of Charles Wistar, Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Rudnytzky 1986: 40)[4]

- “There is a Spring belonging to Chas Wistar in the most romantic scinery [sic] your imagination can conceive. . . The spring comes out a large rock into a bason which is covered with another large rock, then passes beneath a rock under your feet, and bursts out again before it joins the creek.”

- Peale, Charles Willson, 1814, describing Belfield, estate of Charles Willson Peale, Germantown, PA (Miller et al., eds., 1991: 3:239, 266)[5]

- “[15, 27, 29 March] As soon as the weather becomes settled & warm, I will have the Bason walled up with a proper morter, and when that is doing I shall put a Cock to the Leaden pipe to let the water pass out untill the Bason is prepaired to receive it.

- “[14 September] . . . The fountain Bason now holds water completly, and the jet is 12 feet high, and is kept continually playing; Day & night, Rubens has placed all his plants round the Bason, and it is very handsome.” [Fig. 7] back up to History

- Latrobe, Benjamin Henry, 1816, describing his drawing for the creation of a national university on the Mall (Library of Congress)

- “Basin at the mouth of the Tiber, being the entrance of the Canal.” [Fig. 8]

- Peale, Charles Willson, c. 1825, describing Belfield, estate of Charles Willson Peale, Germantown, PA (Miller et al., eds., 2000: 5:383)[6]

- “. . . below the Green house he made a round bason to receive the Water from the cave back of it—and from the fish-pond near the spring-house, to this bason in the Garden is a fall of 15 feet, and in order to have a fountain in the Bason he put log-pipes under ground, and thus had a jet of 13 feet high but of small diameter, in order that it might constantly [be] rising. but unfortunately he make the bore of his logs only of one inch diameter, the consequence was that Frogs in two instances got into the bore of the logs and not being able to pass through all the joints, stopped the water, of course to free the passage of the logs, gave much labour. had these things been foreseen, trouble might have been prevented, by making the bore of the logs of a greater diameter, with other provisions to keep the passage free.”

- Trollope, Frances Milton, 1830, describing Fairmount Waterworks, Philadelphia, PA (1832: 2:43–44)[7]

- “[Fair Mount] is, in truth, one of the prettiest spots the eye can look upon. A broad wear is thrown across the river Schuylkill, which produces the sound and look of a cascade. On the farther side of the river is a gentleman’s seat, the beautiful lawns of which slope to the water’s edge, and groups of weeping-willows and other trees throw their shadows on the stream. The works themselves are enclosed in a simple but very handsome building of freestone, which has an extended front opening upon a terrace, which overhangs the river: behind the building, and divided from it only by a lawn, rises a lofty wall of solid lime-stone rock, which has, at one or two points, been cut into, for the passage of the water into the noble reservoir above. From the crevices of this rock the catalpa was every where pushing forth, covered with its beautiful blossom. Beneath one of these trees an artificial opening in the rock gives passage to a stream of water, clear and bright as crystal, which is received in a stone basin of simple workmanship, having a cup for the service of the thirsty traveller.” [Fig. 9] back up to History

- Mills, Robert, February 23?, 1841, in a letter to Joel R. Poinsett, describing his design for the National Mall, Washington, DC (Scott, ed., 1990: n.p.)[8]

- “The main building for the Institution is located about 300 feet south of the wall fronting the Botanic garden, from which it is separated by a circular road, in the centre of which is a fountain of water from the basin of which pipes are led underground thro’ the walks of the garden, for irrigating the same at pleasure, the fountains may be supplied from the canal flowing near the north wall of inclosure.” [Fig. 10]

- Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), October 1845, “Notes of a Visit to several Gardens in the Vicinity of Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York,” describing the garden of W. H. Corcoran, Washington, DC (Magazine of Horticulture 12: 245)[9]

- “At one end of the garden, is a very neatly constructed rock work, with a basin in the centre, supplied with water from a cistern placed at some distance, but which is only a few feet higher than the water. Small tubes project through the rock work, and by turning a cock, the water is thrown up in several small jets and falls into the basin. Such fountains are constructed at very little expense, and in small gardens they afford much gratification.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1851, describing plans for improving the public grounds in Washington, DC (quoted in Washburn 1967: 55)[10]

- “5th: Fountain Park

- “This Park would be chiefly remarkable for its water features. The Fountain would be supplied from a basin in the Capitol. The pond or lake might either be formed from the overflow of this fountain, or from a filtering drain from the canal.”

Citations

- Langley, Batty, 1728, New Principles of Gardening (1728; repr., 1982: 195–202)[11]

- “General DIRECTIONS, &c. . . .

- “XVIII. That the Intersections of Walks be adorn’d with Statues, large open Plains, Groves, Cones of Fruit, of Ever-Greens, of Flowering Shrubs, of Forest Trees, Basons, Fountains, Sun-Dials, and Obelisks. . .

- “XXXIV. Where Water is easy to be had, always introduce a Basin or Fountain in every Flower and Fruit-Garden, Grove, and other pleasing Ornaments, in the several private Parts of your rural Garden.”

- Chambers, Ephraim, 1741, Cyclopaedia (1741: 1:n.p.)[12]

- “BASON is also used on various occasions for a small reservatory of water: as the bason of a jet d’eau, or fountain; the bason of a port, of a bath, &c. which last Vitruvius calls labrum. See FOUNTAIN.”

- Johnson, Samuel, 1755, A Dictionary of the English Language (1755: 1:n.p.)[13]

- “BASIN. n.s. [basun, Fr. bacile, bacino, Ital. It is often written bason, but not according to etymology.]

- “1. A small vessel to hold water for washing, or other uses. . .

- “2. A small pond. . .

- “5. A dock for repairing and building ships.”

- Forsyth, William, 1802, A Treatise on the Culture and Management of Fruit Trees (1802: 147),[14]

- “Gardens, if possible, should lie near a river, or brook, that they may be well supplied with water. . .

- “If the ground be wet and spewy, it will be proper to make a bason in the most convenient place, to receive the water that comes from the drains, and to collect the rain that falls on the walks.” back up to History

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826: 339, 1009)[15]

- “1718. Reservoirs may be either tanks, cisterns, basins, or ponds. . .

- “1719. Ponds or large basins. . . are reservoirs formed in excavations, either in soils retentive of water, or rendered so by the use of clay. . . Sometimes these basins are lined with pavement, tiles, or even lead, and the last material is the best, where complete dryness is an object around the margin. . . [Fig. 11]

- “7216. Water. . .forms a part of every garden in the ancient style, in the various artificial characters which it there assumes of oblong canals, ponds, basins, cascades, and jets d’eaux. . .” [Fig. 12] back up to History

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828: 2:n.p.)[16]

- “BAS'IN, n. básn. [Fr. bassin; Ir. baisin; Arm. baçzin; It. bacino, or bacile; Port. bacia. . .]

- “1. A hollow vessel or dish, to hold water for washing, and for various other uses.

- “2. In hydraulics, any reservoir of water.

- “3. That which resembles a basin in containing water, as a pond, a dock for ships, a hollow place for liquids, or an inclosed part of water, forming a broad space within a strait or narrow entrance; a little bay.”

- Loudon, Jane, 1845, Gardening for Ladies (1845: 413)[17]

- “Water as an element of landscape scenery, is exhibited in small gardens either in ponds or basins, of regular geometrical or architectural forms; or in ponds or small lakes of irregular forms in imitation of the shapes seen in natural landscape. In general all geometrical or architectural basins of water ought to have the margins of masonry, or at least of stones placed so as to imitate a rocky margin. The reason is, that by these means the artificial character is heightened, and also a colour is introduced between the surrounding grass, vegetation, gravel, or dug-ground, which harmonizes the water with the land. Artificial shapes of this kind should never be of great diameter, because in that case the artificial character is comparatively lost, and the idea of nature occurs to the spectator.” back up to History

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1849, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849: 471)[18]

- “A simple jet. . . issuing from a circular basin of water, or a cluster of perpendicular jets (candelabra jets), is at once the simplest and most pleasing of fountains. Such are almost the only kinds of fountains which can be introduced with propriety in simple scenes where the predominant objects are sylvan, not architectural.” [Fig. 13]

Images

Inscribed

Batty Langley, “Design of a rural Garden, after the new manner,” in New Principles of Gardening (1728), pl. III. “In the Center of this Parterre is an octagon Basin of Water. . .”

Unknown, Derby Garden, [circa 1795–1799], Samuel McIntire Papers, MSS 264, flat file, plan 107. Courtesy of Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum, Rowley, MA. The small circle in the middle of the Kitchen Garden is marked Bason.

Charles Fraser, A Bason and Storehouse Belonging to the Santee Canal, 1803.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Section of the northern course of the canal from the tide in the Elk River at Frenchtown to the forked [oak] in Mr. Rudulph’s swamp, 1803. The Basin is between the canal and the Elk River.

Anonymous, Plan of the Harvard Botanic Garden, c. 1807. “C. Bason or reservoir with running & fragrant waters.”

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Plan of the west end of the public appropriation in the city of Washington, called the Mall: as proposed to be arranged for the site of the university, 1816. “Basin at the mouth of the Tiber, being the entrance of the Canal.”

Robert Mills, Plan of wings and courtyards, South Carolina Insane Asylum, 1821. “Fountain basin.”

J. C. Loudon, “Ponds or large basins” and “Tanks or cisterns,” in An Encyclopædia of Gardening (1826), 339, figs. 286–88.

J. C. Loudon, A garden in the ancient style, in An Encyclopædia of Gardening (1826), 1009, fig. 694. “[Water] forms a part of every garden in the ancient style, in the various artificial characters which it there assumes. . . basins. . .”

Robert Mills, “Plan of the Washington Canal,” 1831.

John Caspar Wild, Fairmount Waterworks, 1838. “There are six basins (a bird’s eye view of which is shown in the vignette).”

Anonymous, "A simple jet. . . the simplest and most pleasing of fountains," in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849), 471, fig. 92. “A simple jet. . . issuing from a circular basin of water. . .”

Associated

Charles Willson Peale, View of the garden at Belfield, 1816.

Robert Mills, Alternative plan for the grounds of the National Institution, 1841.

Attributed

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, “Plan of the public Square in the city of New Orleans, as proposed to be improved. . .” [detail], March 20, 1819.

Harriet De (?), The Duck Pond, c. 1820.

Notes

- ↑ Eliza Lucas Pinckney, The Letterbook of Eliza Lucas Pinckney, 1739–1762, ed. Elise Pinckney (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1972), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Timothy Dwight, Travels in New-England and New-York, 4 vols. (New Haven, CT: T. Dwight, 1821), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Joseph Scott, A Geographical Description of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia: Printed by R. Cochran, 1806), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Kateryna A. Rudnytzky, “The Union of Landscape and Art: Peale’s Garden at Belfield” (Honors thesis, LaSalle University, 1986), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Lillian B. Miller et al., eds., The Selected Papers of Charles Willson Peale and His Family, vol. 3, The Belfield Farm Years, 1810–1820 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Lillian B. Miller et al., eds., The Selected Papers of Charles Willson Peale and His Family, vol. 5, The Autobiography of Charles Willson Peale (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Frances Trollope, Domestic Manners of the Americans, 3rd ed., 2 vols. (London: Wittaker, Treacher, 1832), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Pamela Scott, ed., The Papers of Robert Mills (Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Resources, 1990), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Mason Hovey, “Notes of a Visit to several Gardens in the Vicinity of Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York, in October, 1845,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and all useful discoveries and improvements in Rural Affairs 12, no. 7 (July 1846): 241–48, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Wilcomb E. Washburn, “Vision of Life for the Mall,” AIA Journal 47 (1967): 52–59, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Batty Langley, New Principles of Gardening, or The Laying out and Planting Parterres, Groves, Wildernesses, Labyrinths, Avenues, Parks, &c. (1728; repr. New York and London: Garland Publishing, 1982), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Ephraim Chambers, Cyclopaedia, or An Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences. . . , 5th ed., 2 vols. (London: D. Midwinter et al., 1741–43), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language: In Which the Words Are Deduced from the Originals and Illustrated in the Different Significations by Examples from the Best Writers, 2 vols. (London: W. Strahan for J. and P. Knapton, 1755), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Forsyth, A Treatise on the Culture and Management of Fruit Trees (Philadelphia: J. Morgan, 1802), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, 4th ed. (London: Longman et al., 1826), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jane Loudon, Gardening for Ladies; and Companion to the Flower-Garden, ed. A. J. Downing (New York: Wiley & Putnam, 1845), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America, 4th ed. (1849; repr., Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1991), view on Zotero.