Difference between revisions of "Yard"

V-Federici (talk | contribs) m (→Inscribed) |

V-Federici (talk | contribs) m |

||

| Line 539: | Line 539: | ||

Image:0966.jpg|Charles Bulfinch, Preliminary study for the Elias Hasket Derby House, c. 1795. | Image:0966.jpg|Charles Bulfinch, Preliminary study for the Elias Hasket Derby House, c. 1795. | ||

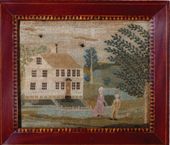

| − | Image:0130.jpg|Anne Pope, Beige House, Birds Flying Over with Foreyard, 1796, in Sotheby’s New York, ''Important American Schoolgirl Embroideries: The Landmark Collection of Betty Ring'' (January 2012), 15. | + | Image:0130.jpg|Anne Pope, Beige House, Birds Flying Over with Foreyard, 1796, in Sotheby’s New York, ''Important American Schoolgirl Embroideries: The Landmark Collection of Betty Ring'' (January 2012), p. 15.<ref name="Sothebys">Sotheby’s New York, ''Important American Schoolgirl Embroideries'' (January 2012), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/I9SQRZDH view on Zotero].</ref> |

Image:0267.jpg|Charles Peale Polk, ''Mrs. Gerrard'', c. 1799. | Image:0267.jpg|Charles Peale Polk, ''Mrs. Gerrard'', c. 1799. | ||

| Line 555: | Line 555: | ||

Image:0203.jpg|Francis Guy, ''Perry Hall from the northwest'', c. 1805. | Image:0203.jpg|Francis Guy, ''Perry Hall from the northwest'', c. 1805. | ||

| − | Image:0125.jpg|Mary Antrim, Brick House with Two Foreyards and Animals, 1807, in Sotheby’s New York, ''Important American Schoolgirl Embroideries: The Landmark Collection of Betty Ring'' (January 2012), 72. | + | Image:0125.jpg|Mary Antrim, Brick House with Two Foreyards and Animals, 1807, in Sotheby’s New York, ''Important American Schoolgirl Embroideries: The Landmark Collection of Betty Ring'' (January 2012), p. 72.<ref name="Sothebys"></ref> |

Image:1152.jpg|Anonymous, ''The Lilacs'', Residence of Thomas Kidder [perspective rendering, front], c. 1810. | Image:1152.jpg|Anonymous, ''The Lilacs'', Residence of Thomas Kidder [perspective rendering, front], c. 1810. | ||

| − | Image:0128.jpg|Mary Moulton, Needlework Sampler, 1813, in Sotheby’s New York, ''Important American Schoolgirl Embroideries: The Landmark Collection of Betty Ring'' (January 2012), 27. | + | Image:0128.jpg|Mary Moulton, Needlework Sampler, 1813, in Sotheby’s New York, ''Important American Schoolgirl Embroideries: The Landmark Collection of Betty Ring'' (January 2012), p. 27.<ref name="Sothebys"></ref> |

Image:1023.jpg|David J. Kennedy, ''Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences'', 1817. | Image:1023.jpg|David J. Kennedy, ''Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences'', 1817. | ||

Revision as of 13:48, December 17, 2020

(Yeard)

See also: Fence, Hedge, Lawn, Orchard, Wall

History

In American landscape vocabulary the term yard connoted an enclosed space, generally contiguous to a building and associated with specific activities related to that building. Hence, the term was often paired with another describing its adjacent structure or use, as in the case of barnyard, stable yard, churchyard, farmyard, poultry yard, kitchen yard, prison yard, cow yard, shipyard, and chunkyard (see also Fence, Hedge, and Wall).

A yard’s layout was dependent upon its particular function and upon such factors as lot boundaries. Generally, however, yards were geometrically regular. J. B. Bordley noted in 1801 that on paper an octagonal farmyard was pleasing to the eye, but that a rectangular shape small enough to attend easily to the animals was, in reality, more practical. While images suggest that yard topography was often relatively level, yards for livestock were sometimes designed with a grade for drainage or runoff, as Samuel Deane (1790) suggested. The surface treatment of yards varied, as indicated by descriptions of southern paved yards and by William Bartram's account (1791) of Native American swept yards in Cuscowilla, Georgia. As early as 1683, dwelling-house yards were described to be turfed or seeded with grass. These lawns, such as the “grass plot” in the yard of Pennsbury Manor, near Philadelphia, continued to be the subject of both horticultural advice and visitors’ admiration through the mid-19th century.

Despite its simple form, the American yard was a complex social space in terms of its function as an activity area and its relation to landscape design. Couplings of the word, such as family yard, door yard, exotic yard, foreyard, and backyard, imply the variety of ways in which these enclosed spaces were used while their ubiquity suggests their significance in the American landscape. In warm climates or warm seasons, the yard adjacent to a dwelling served as an extension of the house for activities as wide ranging as food preparation and socializing. Images of farms and rural residences, such as the naïve view of a Pennsylvania farm with many fences [Fig. 1], depict how the space adjacent to a house (described variously as front yard, family yard, and courtyard) was demarcated from other working areas and from the landscape. Other images represent the yard as a buffer in more densely settled towns and cities, providing separation from neighboring houses and streets. This idea is illustrated in Rufus Hathaway’s painting of Joshua Winsor’s residence [Fig. 2] and Charles Bulfinch’s view of the Elias Hasket Derby House [Fig. 3], both in Massachusetts.

Yards were seen as an extension of a house’s architectural façade, and together they often registered in descriptions as an outward and public presentation of the dwelling’s occupants. References in 18th-century travel accounts and 19th-century periodicals include comments about the appearance of a “well-kept” yard as a sign of its owner’s prosperity and responsible management. In 1827, for example, the New England Farmer noted that a “slovenly door yard is a pretty infallible indication of a slovenly farmer.”

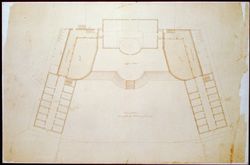

Yards were vital elements of institutional landscapes, including the State House in Philadelphia; Harvard College [Fig. 4]; Princeton College [Fig. 5]; and the College of William and Mary. The term “courtyard” was used for an area enclosed on two sides by buildings and on another by vegetation, as at the Georgia Orphan House Academy [Fig. 6] and a nestling of the space within a building at the Governor’s House in New Bern, NC [Fig. 7]. These spaces created a visual frame for the buildings and also provided places for public gatherings, as suggested by the 1705 notice for burning grievances in the yard of the Capitol of Williamsburg. In addition, they served as areas of social interaction, as seen in numerous projects depicting promenaders in the State House Yard in Philadelphia, or, as in a 1743 engraving, showing students sporting on the grounds at Harvard College [Fig. 8]. Descriptions and representations of prisons, hospitals, and asylums reveal that the enclosed yard provided a secure area for patients or inmates to take fresh air and exercise. This function is illustrated in Robert Waln Jr.’s 1825 description of the Friends Asylum for the Insane, in Charles Bulfinch’s 1818 plan of two wings added to Pleasant Hill to create McLean Asylum [Fig. 9], and in John Hawks’s 1773 design for a prison in Edenton, North Carolina [Fig. 10].

The relationship of the terms “yard” and “garden” is an ambiguous one in the vocabulary of the American landscape. Treatise authors were inconsistent in their explanations of the distinction between these two terms. William Forsyth, for example, in 1802 distinguished a garden as being situated near the house as opposed to a farmyard, which was located at a further distance from the house, although still close enough for direct supervision of laborers. [1] Bordley, on the other hand, writing at almost the same time, noted that a garden within the area near a house was a “Family-yard.” In popular American usage, these terms also appear to have been used inconsistently. Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, numerous writers referred to a site’s “garden and yard,” whereas advertisements and deeds often listed the garden and yard separately. This distinction between more intensively cultivated garden space (located generally near the house) and the more utilitarian yard area is exemplified in the 1810 description that accompanied a sketch of Belfield (view citation). This drawing clearly separated the fenced “yard” surrounding Peale's house from his paled and elaborately planted “garden,” located to the rear. Several images of domestic settings further suggest a distinction between the two types of spaces. Views, such as Ralph Earl’s 1792 portrait of the Chief Justice and Mrs. Ellsworth [Fig. 11], depict white painted fences immediately adjacent to the house, while red paint decorated the more distant fences. Unfortunately no text references exist in which the term “yard” is associated with such images. This explicit visual demarcation of the two spaces may have been representative of a distinction between utilitarian yards (of the sort described in other sources as barn yard, hog yard, etc.) and ornamental yard spaces. Alternatively, the different treatment of the fences may represent properties whose owners would not have claimed to have a “garden” at all; in this case, the images might reflect a distinction between yard and the surrounding agricultural landscapes of pastures, meadows, and field.

A gradual shift in the distinction between yard and garden took place in the first half of the nineteenth century. Martha Ogle Forman's 1824 account of Newark, New Jersey, and articles, such as that in the New England Farmer (1837) about “Front Yards,” mark an increasingly common pattern for private residential landscaping in which flower borders, shrubbery, and gardens are included within the space that was designated as a yard. Such designers as A. J. Downing (1849) and William H. Ranlett (1849) advocated that the yard should complement a residence, and each produced plans that became models for early suburbias. Their writings, particularly those disseminated through periodicals, were critical in the replication of such designs throughout America.

—Elizabeth Kryder-Reid

Texts

Usage

- Anonymous, 1647, describing a rental agreement in York County, VA (quoted in Lounsbury 1994: 413)[2]

- “[Richard Bernard agrees to] maintain the old dwelling house and quartering houses and Tobacco houses in repair, as well as the pales about the yard and gardens.”

- Fitzhugh, William, April 1686, describing Greensprings, VA (quoted in Lockwood 1934: 2:46)[3]

- “[The orchard was] well fenced in with Locust fence, which is as durable as most brick walls, a Garden, a hundred feet square, well pailed in, a Yeard where in is most of the foresaid necessary houses [domestic outbuildings], pallizado’d in with locust Punchens, which is as good as if it were walled in & more lasting than any of our bricks.”

- Penn, William, August 16, 1683, describing Pennsbury Manor, country estate of William Penn, near Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Blome 1687: 117)[4]

- “6. English Grass-Seed takes well; which will give us fatting Hay in time. Of this I made an Experiment in my own Court-Yard, upon Sand that was digg’d out of my Cellar, with Seed that had lain in a Cask, open to the Weather two Winters and a Summer.”

- Penn, William, c. 1687, describing Pennsbury Manor, country estate of William Penn, near Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Thomforde 1986: 1)[5]

- “I should be glad to see a draugh of Pennsberry wch an Artist would quickly take, wth ye land scip of ye hous, out houses, orchards, also wt grounds you have cleered wt improvemts made. an account how the peach & apple orchards grow; Bear. if any walks be made, & steps at ye water & how yt garden next ye water towards ye house, is layd out & thrives, how farr you advance . . . wt fence about ye yards gardens & orchards.”

- Anonymous, November 10, 1705, describing in the Journals of the House of Burgesses construction resolutions in Williamsburg, VA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “Ordered That the Grievances from King William County be Burnt on Wednesday next by the Sheriff on York County in the Capitol Yard.”

- Anonymous, October 20, 1730, entry in the Essex County Order Book pertaining to Essex County, VA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “To James Griffin (for which he is to remove ye rubish and level ye yard about the new courthouse) . . . 700 lbs. tob.”

- Anonymous, February 14, 1736, describing a property for sale in Charleston, SC (South Carolina Gazette)

- “To be Sold by John Laurens a Dwelling House, fronting on the Market-Square in Charlestown, divided into four commodious Tenements, with convenient Kitchins, yards and Gardens.”

- Kalm, Pehr, September 19, 1748, describing Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery, vicinity of Philadelphia, PA (1937: 1:41)[6]

- “Mulberry trees are planted on some hillocks near the house and sometimes even in the court-yards of the house.”

- Birket, James, September 11, 1750, describing Harvard College, Cambridge, MA (1916: 18)[7]

- “Consists of three Separat Brick buildings . . . One of which is called Stoughton hall, And although the 2 wings do not Join to the Middle buildg yet they are So placed As to form a very handsom Area or Courtyard in the Middle.”

- Anonymous, 1753, describing in the South Carolina Gazette a dwelling in Beaufort County, SC (quoted in Lounsbury 1994: 413)[2]

- “[The dwelling had] a garden at the south front, and yard lately paved in.”

- Anonymous, September 16, 1765, describing in the Queen Anne’s County Deed Book Holt Castle Hill, Queen Anne’s County, MD (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “Upon the land called Holt Castle Hill . . . a new pateo yard.”

- Ambler, Mary M., 1770, describing Mount Clare, plantation of Charles and Margaret Tilghman Carroll, Baltimore, MD (1937: 166)[8]

- “there is also a Handsome Court Yard on the other Side of the House.”

- Fithian, Philip Vickers, March 18, 1774, describing Nomini Hall, Westmoreland County, VA (1943: 108)[9]

- “From the front yard of the Great House, to the Wash-House is a curious Terrace, covered finely with Green turf.”

- Hazard, Ebenezer, May 31, 1777, describing the College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA (Shelley, ed., 1954: 405)[10]

- “At this Front of the College is a large Court Yard, ornamented with Gravel Walks, Trees cut into different Forms, & Grass. The Wings are on the West Front, between them is a covered Parade, which reaches from the one to the other; the Portico is supported by Stone Pillars: opposite to this Parade is a Court Yard & a large Kitchen Garden.”

- Washington, George, March 10, 1785, describing Mount Vernon, plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (ed. Jackson and Twohig, 1978: 4:100)[11]

- “Sent my Waggon with the Posts for the Oval in my Court Yard to be turned by a Mr. Ellis at the Snuff Mill on Pohick & to proceed from thence to Occoquan for the Scion of the Hemlock to plant in my Shrubberies.” [Fig. 12]

- Cutler, Manasseh, July 12, 1787, describing Princeton University, Princeton, NJ (1987: 1:245)[12]

- “The College (Nassau Hall) is spacious, built of stone, and stands on the highest ground in the town. It fronts to the north, and toward the street, and has before it a very large yard, walled in with stone and lime.”

- Morse, Jedidiah, 1789, describing State House Yard, Philadelphia, PA (1789; repr., 1970: 331)[13]

- “The state house yard, is a neat, elegant and spacious public walk, ornamented with rows of trees; but a high brick wall, which encloses it, limits the prospect.”

- Hamilton, William, May 2, 1789, in a letter to his secretary, Benjamin Hays Smith, describing The Woodlands, seat of William Hamilton, near Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Madsen 1988: A4–A5)[14]

- “The Exotic yard if I may so call it & all the space between the green H & the shop should be made clean & neat as I have no doubt there will be visitors to view them.”

- Bartram, William, 1791, describing a typical house in Cuscowilla, GA (1928: 168–69)[15]

- “The dwelling stands near the middle of a square yard, encompassed by a low bank, formed with the earth taken out of the yard, which is always carefully swept.”

- Bartram, William, 1791, describing settlements of the Muscogulge and Cherokee Indians (1928: 406)[15]

- “The pyramidal hills or artificial mounts, and highways, or avenues, leading from them to artificial lakes or ponds, vast tetragon terraces, chunk yards,*and obelisks or pillars of wood, are the only monuments of labour, ingenuity and magnificence that I have seen worthy of notice, or remark.

- “*Chunk yard, a term given by white traders, to the oblong four square yards, adjoining the high mounts and rotundas of the modern Indians.—In the centre of these stands the obelisk, and at each corner of the farther end stands a slave post or strong stake, where the captives that are burnt alive are bound.”

- Smith, William Loughton, May 5,1791, describing a settlement near Salem, NC (1917: 73)[16]

- “The church yard is on a hill above the town, surrounded by shady groves.”

- Dwight, Timothy, 1796, describing New Haven Green, New Haven, CT (1821: 1:184)[17]

- “A considerable proportion of the houses have court-yards in front, and gardens in rear. The former are ornamented with trees, and shrubs; the latter are luxuriantly filled with fruit-trees, flowers, and culinary vegetables. The beauty, and healthfulness, of this arrangement need no explanation.”

- Dwight, Timothy, 1796, describing Hallowell, ME (1821: 2:218)[17]

- “Hallowell is a very pretty town, built on an irregular, or rather steep, descent. This slope, though interrupted, is handsome, and furnishes more good building spots, than if it had been an uniform declivity, and at the same time equally steep. Then all the grounds would have descended too rapidly. Now they furnish a succession of level surfaces for gardens, house-plats, and court yards; and are thus very convenient, as well as sometimes very handsome.”

- Drinker, Elizabeth, April 10, 1796, describing her garden in Philadelphia, PA (Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Diaries of Elizabeth Drinker)

- “Our Yard and Garden looks most beautifull, the Trees in full Bloom, the red, and white blossoms intermixt’d with the green leaves, which are just putting out flowers of several sorts bown [bloom?] in our little Garden—what a favour it is, to have room enough in the City, and such elegant room,—many worthy persons are pent up in small houses with little or no lotts, which is very trying in hott weather.”

- Dwight, Timothy, 1799, describing Province Town, MA (1822: 3:95–96)[17]

- “It is said, that there are two or three gardens at some distance from the town; and some of the inhabitants cultivate a few summer vegetables in their court-yards.”

- Dwight, Timothy, 1799, describing a Shaker community in New Lebanon, NY (1822: 3:149)[17]

- “Their church, a plain, but neat building, had a court-yard belonging to it, which was a remarkably ‘smooth-shaven green.’ Two paths led to it from a neighbouring house, both paved with marble slabs.”

- Ogden, John Cosens, 1800, describing a girls’ school in Bethlehem, PA (1800: 14)[18]

- “Since the applications to receive pupils from abroad, have become so frequent and numerous, a new building has been erected for their use, upon a similar model, with the sisters house. A small court yard, or grass plat, is between these buildings.”

- Codman, John, August 24, 1800, describing the Grange, estate of Dr. John and Sarah Codman, Lincoln, MA (Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, Codman Family Manuscript Collection: Box 119, Folder 1, 923)

- “I do not know any place in America so much like Gentlemen’s seats in this country as Lincoln (dear Lincoln) all it wants is the foreyard all knocked away & the house to stand in the midst of a lawn & so surrounded with trees that you can see neither road nor buildings from it.”

- Drayton, Charles, November 2, 1806, describing The Woodlands, seat of William Hamilton, near Philadelphia, PA (1806: 54—58)[19]

- “The Approach, its road, woods, lawn & clumps, are laid out with much taste & ingenuity. Also the location of the Stables: with a Yard between the house, stables, lawn of approach or park, & the pleasure ground or garden. . . .

- “The Fences separating the Park-lawn from the Garden on one hand, & the office yard on the other, are 4 ft. 6 high. . . .

- “The Stable Yard, tho contiguous to the house, is perfectly concealed from it, the Lawn, & the Garden. . . . From the Cellar one enters under the bow window & into this Screen, which is about 6 or 7 feet square. Through these, we enter a narrow area, & ascend some few Steps [close to this side of the house,] into the garden—& thro the other opening we ascend a paved winding slope, which spreads as it ascends, into the yard. This sloping passage being a segment of a circle, & its two outer walls concealed by loose hedges, & by the projection of the flat roofed Screen of masonry, keeps the yard, & I believe the whole passage out of sight from the house—but certainly from the garden & park lawn. . . .

- “The Stables, & sheds, form the 3rd side of this three sided yard—The stables are seen from the front door of the house, over the hedge that screens the Yard.”

- Martin, William Dickinson, May 14, 1809, describing Richmond, VA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “Every private yard is decorated with the handsomest shade trees of which our Country boasts, each apparently contesting the palm of beauty.”

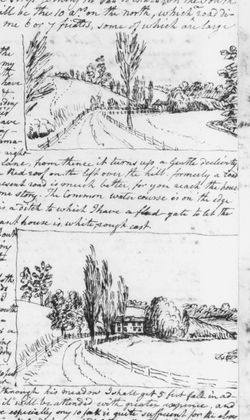

- Peale, Charles Willson, July 29, 1810, describing Belfield, estate of Charles Willson Peale, Germantown, PA (Miller et al., eds., 1991: 3:56)[20]

- “In this view the stone steps at the End of the house is seen, which lead to the yard in front of the Garden, the Garden pails are on a stone wall on which grows Creepers now in full bloom they are a fine crimosen [sic] bell flowers in Clusters and an abundance of humming birds are daily sucking the honey. Green Gages, Damsons & quinces are along this wall.” [Fig. 13] back up to History

- Gerry, Elbridge Jr., July 1813, describing Mount Vernon, plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (1927: 173–74)[21]

- “On one side is an elegant garden, which has a small white house for the gardener, and a row of brick buildings back of it. All these are enclosed by a wall in an oval form, and leaving a large area before the house for the yard.”

- Gerry, Elbridge Jr., July 1813, describing the White House, Washington, DC (1927: 182)[21]

- “The building is of freestone and is approached by a yard, which becomes oval at the door.”

- Lambert, John, 1816, describing Charleston, SC (2:125)[22]

- “The houses in Meeting-street and the back parts of the town are many of them handsomely built; some of brick, others of wood. They are in general lofty and extensive, and are separated from each other by small gardens or yards, in which the kitchens and out-offices are built.”

- Forman, Martha Ogle, 1818, describing a plantation in Cecil County, MD (quoted in Lounsbury 1994: 414)[2]

- “[On the plantation, time was spent] preparing for company, made cake, and had all the yards swept clean.”

- Latrobe, Mary Elizabeth, April 18, 1820, describing the home of Benjamin Henry Latrobe, New Orleans, LA (1951: 181)[23]

- “. . . one side of the yard is enclosed by Altheas 30 feet high forming a Solid mass of foliage. . . . Our lot at the back of the house from a gate in the yard is filled with fig trees, Altheas, liburnums, and Myrtles, promising a great crop of figs & flowers.”

- Silliman, Benjamin, 1824, describing Charlestown, NH (1824: 420)[24]

- “there is an extreme degree of neatness in the fields, gardens, and door yards.”

- Forman, Martha Ogle, August 20, 1824, describing Newark, NJ (1976: 185)[25]

- “Newark is a very pretty little Village. I was pleased with its fine Churches, and wide streets, and its large squares of Grass, with its neat white houses and little yards in front filled with shrubbery.”

- Waln, Robert, Jr., 1825, describing the Friend’s Asylum for the Insane, near Frankford, PA (1825: 231)[26]

- “In the rear of the wings are situated the yards or airing grounds, for the use of the male and female patients, separated by the space in the rear of the centre building, and each containing about five-ninths of an acre of ground, in grass, surrounded by walks.”

- Bernhard, Duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, 1828, describing the Bloomingdale Asylum for the Insane, New York, NY (quoted in Little 1972: 64)[27]

- “There are subterraneous passages from the corridors to the large yard which is surrounded by walls, and serve for walking, exercise, and play. In the middle of each yard is a shelter with benches for bad weather. . . . In the whole establishment great cleanliness is preserved; but still the institution appeared to me less perfect than the Asylum of Boston, or of Glasgow, Scotland.”

- Smith, Margaret Bayard, March 11, 1829, in a letter to Mrs. Jane Kirkpatrick, describing the White House, Washington, DC (1906: 295)[28]

- “Your father, Mr. Wood, Mr. Ward, Mr. Lyon, with us, we set off to the President’s House, but on a nearer approach found an entrance impossible, the yard and avenue was compact with living matter.”

- Committee of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1830, describing Sweet Briar, the seat of Samuel Breck, vicinity of Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Boyd 1929: 424) [29]

- “The garden has been made at considerable expense, and may contain, including the plant yard and shrubbery, about two acres.”

- Bell, Caroline, July 10, 1831, describing Plaqumine, Iberville, LA (The Historic New Orleans Collection, Butler Family Papers, folder 545, mss 102)

- “for my part my dear I have neither taste (altho’ I admire flower Gardens as much as any one) or time to devote to those things at least not as much as is necessary—I hope you will be more fortunate than I have been, I have made every exertion to have a great many Monthly Roses, without success, as I do not think that a dozen have taken—owing intirely, I believe, to the Yards being in White Clover—I have been eaqually unfortunate with the most beautiful, of all flowering shrubs—The flowering Pomgrancete [sic]— I’m sure I have set out the Pomigranite, the Rose and many other things half a dozen times—When they have died—Mr Bell thinks we will be obliged to cultivate the Yard to have things do well in it— I am of the same opinion—however we are in hopes that the Bermuda Grass sods which we have set about thro’ the yard—in time—will get the better of the Clover. Much, very much, is yet to do here, to render our place either pleasing to the eye or comfortable.”

- Bryant, William Cullen, August 23, 1832, describing Sangamon County, IL (1975: 356–57)[30]

- “The soil is a deep rich black, fine mould. . . . It is in short the richest garden soil. . . . It wants turf—the grass grows thin in the fields and prairies, and the sides of the road and the door yards and immediate vicinity of the dwellings are covered with weeds—mostly smartweed and mayweed.”

- Weeks, Mary Clara, June 10, 1834, describing Shadows-on-the-Teche, New Iberia, LA (quoted in Turner 1993: 94)[31]

- “Every (one) is advising me to move into the new house—the yard is levelled off. It looks very neat and pretty. The Dr. and Mr. Smith advise it on account of health as we are much crowded. I cannot bear to leave the old place while you are away.”

- O’Conner, Rachel, July 26, 1836, in a letter to Mary Clara Weeks, describing Evergreen Plantation, estate of Rachel O’Conner, Bayou Sarah, LA (quoted in Turner 1993: 483)[31]

- “If you could see the old House yard, you would be pleased with the appearance it makes at this time the crape myrtle trees in full bloom, perfectly red, and many other flower trees and shrubs. I don’t think it ever look’d so pretty before.”

- Barber, John Warner, and Henry Howe, 1841, describing Kinderhook, NY (1841: 119)[32]

- “Many of the dwellings have spacious yards and gardens decorated with shrubbery; and groves of trees interspersed here and there give this place a pleasing aspect.”

- Kirkbride, Thomas S., 1841, describing the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, Philadelphia, PA (1851: 18)[33]

- “On the north and south side of the building are private yards, one hundred and seventeen feet wide, and extending two hundred feet from the return wings which form one of their sides. These yards are enclosed by a tight board fence seven and a half feet high, and are surrounded with a brick pavement, which affords a fine promenade at all seasons.”

- B., P., January 1844, “Progress of Horticulture in Rochester, NY” (Magazine of Horticulture 10: 16)[34]

- “The maple and the buttonwood are stationed along the sidewalks, to protect the dwellings from the summer’s heat—the door-yards, too, have their respective ornaments, proportioned to the means, or rather taste, of the occupant, for it is not always the most wealthy that bestow the most attention to the establishment of their homes.”

- Earle, Pliny, January 1848, describing Bloomingdale Asylum for the Insane, New York, NY (American Journal of Medicine 10: 63–64)

- “Airing Courts, or Yards.—There are three of these courts for the men, and four for the women. They are, with one exception, well shaded with trees, and three of them have large bowers covered with roofs, and furnished with seats for all the patients admitted into the courts. . . .

- “The Physicians who object to yards, or courts, advocate, as a substitute, open verandahs guarded by lattice-work, such as are found at the Massachusetts State Lunatic Hospital, and at some of the other institutions of this country.”

- Kirkbride, Thomas S., April 1848, describing the pleasure grounds and farm of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, Philadelphia, PA (American Journal of Insanity 4: 348, 349)[35]

- “The pleasure grounds of the two sexes are very effectually separated on the eastern side, by the deer-park, surrounded by a high palisade fence, but the Park itself is so low that it is completely overlooked from both sides; and the different animals in it are in full view from the adjoining grounds used by the patients of both sexes.

- “At the extreme end of the deer-park, it is joined by the drying-yard which completes the separation of the sexes in that direction. In this yard, are the wash-house and the pump and pond from which water is raised into the tanks in the dome of the centre building. This pond is supplied from various springs on the premises, and there is ample space in the yard for drying clothes in fine weather.

- “East of the entrance is the private yard and residence of the Physician of the Institution, being the mansion house on the farm when purchased by the Hospital. The vegetable garden containing three and a half acres is next, and in it are the green-house, hot-beds, seed-houses, &c. . . .

- “There is a single private yard of good size for gentlemen who wish to be less public than in the grounds, or for those whose mental condition renders more seclusion desirable. This yard is planted with trees and had broad brick walks passing round it. . . .

- “In connexion with each lodge, as now enlarged or about to be, are three small yards paved with brick, and accessible to the patients of the respective divisions with which they are connected.

- “The work-shop and lumber-yard are just within the main entrance on the west—adjoining which is a fine grove, in which is the gentlemen’s ten-pin alley. . . .

- “As on the men’s side, there is a private yard for females, and the flower-garden in front of the lodge, and the paved yards connected with it are similarly arranged.

- “The semi-circular yard, on the western side of the main building is surrounded by flower borders, contains the circular pleasure Rail-road, and is used at different hours, by patients of both sexes.”

- Anonymous, 1850, describing slave life in America (quoted in Breeden 1980: 121)[36]

- “The negroes should be required to keep their houses and yards clean, and in case of neglect, should receive such punishments as will be likely to insure more cleanly habits in future.”

- Weeks, Harriet Clara, March 27, c. 1850, describing her home in Louisiana (quoted in Turner 1993: 516)[31]

- “I have been very busy since my return home found everything about the yard & garden in pretty good order. Still I find plenty to do in the garden; spend most of my time in there. The trees you sent down are nearly all living. The cotton and china trees are putting out very prettily.”

- Smith, C., May 1851, “Notes on the Culture of Melons at the North” (Horticulturist 6: 228)[37]

- “New-York, for instance, now one of the largest cities in the world, has no public park, whatever—no breathing place, no grounds for the exercise and refreshment of her jaded citizens— for to call the little yards of land, covered with turf, and planted with trees, in various parts of the town, parks, is as much a misnomer as it would be to spread one’s handkerchief down on the floor of the rotunda of the capitol, and call it a carpet.”

Citations

- Switzer, Stephen, 1718, Ichnographia Rustica (1718; repr., 1982: 2:136–37)[38]

- “COURT-YARDS are by the Latins call’d Area, quia ibi arescunt fruges, says Varro, an ancient Writer of Husbandry amongst the Romans; and with us, Court-Yards; Court, from the French, and Yard, a Term of our own, and is, in its proper Signification, an open, airy Drying-Place, quia exaruerit, as the Dictionary expresseth it, and bounded with a Wall, Hedge, or Pale, or some Circumscription, as Courts of Law and Justice are; but when particularly apply’d to the Matter in Hand, signifies those little Divisions that lye contiguous to a Gentlemen’s House, and other his Offices of Convenience.”

- Chambers, Ephraim, 1741–43, Cyclopaedia (1743: 2:n.p.)[39]

- “YARD-LAND . . . Virgata terrae, or virga terrae, is a certain quantity of land, various according to the place.—At Wimbleton in Surrey, it is only 15 acres; but in most other countries it contains 20, in some 24, in some 30, and in others 40, to 45 acres. See ACRE.”

- Johnson, Samuel, 1755, A Dictionary of the English Language (1755: 1:n.p.)[40]

- “CHURCHYARD. n.s. The ground adjoining to the church, in which the dead are buried; a cemetery.”

- Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufacturers and Commerce, 1769, The Complete Farmer (1769: n.p.)[41]

- “FARM-YARD, the place adjoining to the farm-house, where cattle are foddered, and several other necessary works, belonging to the farm, are performed.”

- Sheridan, Thomas, 1789, A Complete Dictionary of the English Language (1789: n.p.)[42]

- “YARD, ya’rd. s. Inclosed ground adjoining to a house.”

- Deane, Samuel, 1790, The New-England Farmer (1790: 17)[43]

- “BARN-YARD, a small piece of inclosed ground contiguous to a barn, in which cattle are usually kept. It should have a high, close, and strong fence, both to shelter the beasts from the force of driving storms, and to keep the most unruly ones from breaking out. . . .

- “The ground of a yard for this purpose should be of such a shape as to retain all the manure.”

- Bordley, J. B., 1801, Essays and Notes on Husbandry and Rural Affairs (1801: 74–75, 79–80)[44]

- “It is an especial object in this design that the whole [farm] yard and its buildings, should be in view from the mansion; and that they be constructed at a proper distance, neither too near nor too far from the mansion. . . . The yard ought to be compact; and the doors of the buildings, and the gates of the yard, seen from the mansion. Plate

- I. *[footnote] It is not to save ground that compactness is here desired; but that attentions due to the live stock may be performed in the readiest and best way. A yard containing cattle always housed, is never to be littered with straw. . . . On paper, an octagon form of a farm yard is pleasing to the eye: but the above is preferred.

- “The homestead includes this yard; together with its stackyard, the garden, nursery, orchard, and some acres of grass; enough for occasionally letting mares, or sick beasts run on, at liberty.

- “The Family-yard, is a barrier against farmyard intrusions. It is covered with a clean, close sward of spire grass. Its margin alone may be admitted to grow flowers. It is fenced by a sunk fence; on the top whereof may be, a low, light palisade; which with the bank may be hid by rose trees planted in the ditch, which is to slope gently up towards the mansion. The white rose bush or tree is the hardiest, tallest, and handsomest sort; but the damask is best for yielding the fine distilled water.”

- Anonymous, May 18, 1827, “Door Yards” (New England Farmer 5: 340)[45]

- “Some people pretend that a man’s character may be learned from the shape of his nose, or the shape of his head. Honest people may be permitted to doubt whether this is so; but that a man’s character, in some particulars, may be learned from the appearance of his door yard, no reasonable man can doubt. It is suggested in the new Williamstown paper, that one reason why so many door yards are neglected, is that it is a spot of doubtful jurisdiction, neither falling exactly within the scope of the word “farm,” which it is the province of the man to oversee, nor being properly in the house, where the woman reigns, but if there is any question of this sort it ought to be settled without delay, for a slovenly door yard is a pretty infallible indication of a slovenly farmer, a slovenly wife, and a slovenly house. Old leaves, sticks, chips, bones and old weeds, a broken, falling fence, in short any thing but a neat door yard is a suspicious circumstance. The paper aforesaid suggests that ‘without entering on the delicate question of right, that this province be made over to the ladies; and that they have full power to call upon any idle man or boy about the house to aid and abet them in its due regulation.’

- “We think this a good proposition, for where there is neither an idle man or an idle boy, the door yard is as neat as wax work.—Springfield pa.”

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828: 2:n.p.)[46]

- “YARD, n. [Sax. geard, gerd, gyrd, a rod, that is, a shoot.] . . .

- “2. [Sax. gyrdan, to inclose; Dan. gierde, a hedge, an inclosure; gierder, to hedge in, Sw. garda.] An inclosure; usually, a small inclosed place in front of or around a house or barn. The yard in front of a house is called a court, and sometimes a court-yard. In the United States, a small yard is fenced round a barn for confining cattle, and called barn-yard, or cow-yard.”

- Anonymous, April 1, 1837, “Landscape Gardening” (Horticultural Register 3: 121–23)[47]

- “The first thing, when a spot is fixed on for a house, if it be in a new country especially, is to cut down all the native trees and shrubs within several rods of it. The proprietor then sets to work and applies his whole resources to build as large a house as possible. When the work is completed his funds are exhausted; he can make no further improvements about his house; it is left standing, dreary and alone, perhaps unpainted, an unsightly broken fence to enclose it, and the nakedness of the yard only relieved by an old barrel, a pile of wood, and broken hoops and boards. Sometimes indeed a more finished appearance is presented; the house is neatly painted, a handsome grass plat extends before it, and a picket fence encircles it.”

- Anonymous, July 12, 1837, “Front Yards” (New England Farmer 16: 3)[48]

- “It is high time front yards were attended to— the fences repaired, the trees and shrubbery pruned, and the rubbish which has accumulated during the winter, removed. Nothing is more indubitably indicative of the husbandry of the farm, and the order of the house, than the condition of the front yard—and whenever and wherever you see one with its fences broken down, gates unhung, and its interior littered up with old shoes, dead cats, broken jugs, &c., you may call the man a sloven, and his wife a slut, without exposing yourself to be mulet in damages in an action for slander. . . .

- “Many front yards are neglected on account of the unsettled state of the law regarding the title to the ‘locus in quo.’ Some contend that the front yard is a part of the farm, and under the supervision and control of the husband; while others insist that it is a ‘part and parcel’ of the house, and, being such, is within the jurisdictional limits of the wife; and consequently, subject to her government and entitled to her protection. We confess our attainments in martial law are not sufficient to enable us to adjudicate this ‘questio vexata,’ but we are inclined to the opinion, that the husband owns the right of soil, subject, however, to the carement of the wife; and that for certain purposes, such as building and repairing fences, planting and pruning shrubbery, dressing flower-beds, &c., both have a right of entry and possession. But whatever may be the law, there is no doubt if the time often consumed in mooting it, was spent in improving the yard, it would present a very different appearance. There are, however, certain members of the family to whom the care and management of this matter more especially belongs—we mean the daughters—and a young gentleman of taste and judgement, ‘in search of a wife,’ would be about as likely to ‘fall in love’ with a young lady, who neglected her front yard, as he would if he first saw her at church with a hole in her stocking.”

- Farmer, Franklin [pseud.], April 1, 1838, “Front Yards—Shrubbery—Flowers” (Horticultural Register 4: 137–39)[49]

- “Let every farmer, therefore, appropriate a liberal allowance of ground for a front-yard to his house.—It should be expansive enough to permit the execution of a regular design, in laying out the lines for walks, groves, rows of trees, shrubbery and flowers. It should be handsomely graded, sloping downwards from the house, in front and on each hand. Set it in blue grass, and of course enclose it by a neat, substantial paling or fence, painted white. In the selection of the trees, shrubbery and flowers, consult the taste of your ‘better half;’ and don’t spare any expense she may require, in order to gratify her taste. . . .

- “Never permit the suggestions of a momentary cupidity, to induce you to graze your front-yard. The grass may look luxurious and tempting; and it may seem ‘a sin’ to lose it; but better to mow or shear your yard than to graze it.”

- Hooper, Edward James, 1842, The Practical Farmer, Gardener and Housewife (1842: 317–18)[50]

- “PIGEONS. . . . A pretty object in a poultry yard is a wooden structure or dovecote raised from the ground on one or more high posts.”

- Ranlett, William H., 1849, The Architect (1849; repr., 1976: 1:38, 60, 65)[51]

- “The great number of cottages which have been erected in the suburbs of London in latter years, has afforded the finest opportunity for the application of improved taste and skill in Cottage Architecture, and the result is a vast amount of rural scenery, comprising, in great harmony, the most chaste and tasteful Architecture, and highly improved gardens and yards with their exquisite flowers, shrubs and vines, constituting views which are admired by visitors from all countries. One of the chief sources of the beauty of those rural residences, is the positions of the houses on the lots, which is back sufficient to afford front yards for the cultivation of plants and vines which are arranged and trained in graceful combinations with the architectural features, thus hightening [sic] the general effect by promoting the influence of the various parts. This style is well adapted to a large portion of the surface and scenery of the United States, especially those portions in the higher latitudes. . . .

- “The want of a convenient front yard is a great detriment to a residence for which there is no compensation. Such a yard places a house back from the street, and by that means relieves the family of much of the dust and noise by which they would otherwise be annoyed. It adds greatly to the taste and beauty of a dwelling, and thus it renders it decidedly more valuable. It is likewise beneficial to the family by its tendency to foster good taste, especially if it is cultivated with flowers and ornamental shrubs, as a front yard should be. This affords also innocent and useful amusement and pastime and the effects of such employments are always of a genial character, as they cultivate habits of industry and attention, and improve the taste and other fine feelings of our nature. . . .

- “A plot of village property 724 feet by 488. It is divided into 16 lots, with the cottages placed 30 ft. from the street, and a carriage way through from the front to the rear. A wood-house, wash-room, and two water closets under one roof directly in the rear of each house; and stable and coach-house on the rear of the lot at the lane; and near it the poultry-house and yard.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, February 1849, “On the Drapery of Cottages and Gardens” (Horticulturist 3: 354)[52]

- “A porch of rustic trellis-work was built over the front door-way, simple and pretty hoods upon brackets over the windows, the door-yard was all laid out afresh, the worn out apple trees were dug up, a nice bit of lawn made around the house, and pleasant groups of shrubbery, (mixed with two or three graceful elms,) planted about it. But, most of all, what fixes the attention, is the lovely profusion of flowering vines that enrich the old house; and transform what was a soulless habitation, into a home that captivates all eyes.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1850, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850; repr., 1968: 271)[53]

- “There [in a villa] should be room for a kitchen yard or court, connected with a passage or a short path to the stable, and all quite turned away from the lawn or entrance side of the house.”

Images

Inscribed

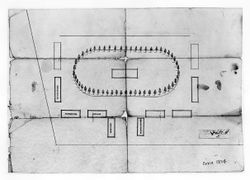

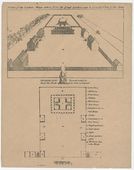

William Bartram, “Arrangement of the Chunky-Yard, Public Square, and Rotunda of the modern Creek towns,” in “Observations on the Creek and Cherokee Indians” (1789), from Transactions of the American Ethnological Society 3, part 1 (1853): 54, fig. 3.

William Bartram, Plan of a Cherokee Private “Habitation,” in “Observations on the Creek and Cherokee Indians” (1789), from Transactions of the American Ethnological Society 3, part 1 (1853): 56, fig. 5.

William Bartram, “Plan of the Ancient Chunky-Yard,” in “Observations on the Creek and Cherokee Indians” (1789), from Transactions of the American Ethnological Society 3, part 1 (1853): 52, fig. 2. “The banks enclosing the yard are indicated by the letters b, b, b, b.”

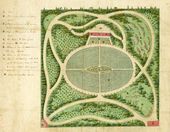

Pierre Pharoux, “General Map of the honorable Wm. frederic Baron of Steuben’s Mannor”, c. 1793.

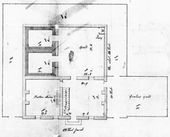

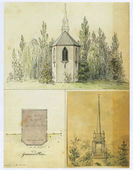

William Russell Birch, View of the Chapel/Smokehouse at Springland, with Steeple Detail and Plan, c. 1800. "This part in the yard. . ." inscribed in Ground Plan to the left.

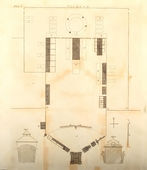

Anonymous, Plan of the Harvard Botanic Garden, c. 1807. Harvard University Herbaria and the Botany Libraries, Cambridge, Mass.

Charles Willson Peale, Sketches of Belfield, 1810.

J. C. Loudon, Plan of farmyard, garden offices and hot-houses at Cheshunt Cottage, in The Gardener’s Magazine 15, no. 117 (December 1839): 642, fig. 159. Yard indicated at 17, 41, 55, 56, 59, 76.

Thomas S. Sinclair, “Plan of the Pleasure Grounds and Farm of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane at Philadelphia,” in Thomas S. Kirkbride, American Journal of Insanity 4, no. 4 (April 1848): pl. opp. 280.

Frances Palmer, “Ground Plot of 4-1/4 Acres,” in William H. Ranlett, The Architect (1851), vol. 2, pl. 6. "D" marks a "a stable yard"

Frances Palmer, “Ground Plot,” in William H. Ranlett, The Architect (1851), vol. 2, pl. 29. "H H, hog pen and yard. . . ; K, barn yard ; P, a stone wall, . . . and on the top a low open fence from the fowl yard (I), south 200 feet. . . "

Anonymous, House Lot, Gardens, and Orchard of Bacon’s Castle (after an 1843 survey plan), 1911, in Peter Martin, The Pleasure Gardens of Virginia: From Jamestown to Jefferson (1991), 10. fig. 5.

Associated

Anonymous, A View of Mount Vernon, c. 1790.

Frances Palmer, “A plot of village property 724 feet by 488,” in William H. Ranlett, The Architect (1849), vol. 1, pl. 48.

Anonymous, “Plan of a Suburban Garden,” in A. J. Downing, ed., Horticulturist 3, no. 8 (February 1849): pl. opp. 353.

Attributed

Anonymous, Fairhill, The Seat of Isaac Norris Esq., 18th century.

William Burgis, [A prospect of the colleges in Cambridge in New England.], 1743.

John Rose, attr., The Old Plantation, c. 1785—90.

Jonathan Budington, View of the Cannon House and Wharf, 1792.

Rufus Hathaway, A View of Mr. Joshua Winsor’s House &c., 1793—95.

Anne Pope, Beige House, Birds Flying Over with Foreyard, 1796, in Sotheby’s New York, Important American Schoolgirl Embroideries: The Landmark Collection of Betty Ring (January 2012), p. 15.[54]

Charles Fraser, Brabants: The Seat of the Late Bishop Smith, April 18, 1800.

Charles Fraser, Ashley Hall, 1803.

Francis Guy, Mount Deposit from the North, 1805.

Mary Antrim, Brick House with Two Foreyards and Animals, 1807, in Sotheby’s New York, Important American Schoolgirl Embroideries: The Landmark Collection of Betty Ring (January 2012), p. 72.[54]

Mary Moulton, Needlework Sampler, 1813, in Sotheby’s New York, Important American Schoolgirl Embroideries: The Landmark Collection of Betty Ring (January 2012), p. 27.[54]

Charles H. Wolf, attr., Pennsylvania Farmstead with Many Fences, c. 1847.

Mary Steiner Denke (possibly), View of Salem from the West, c. 1852.

Notes

- ↑ William Forsyth, A Treatise on the Culture and Management of Fruit Trees (Philadelphia: J. Morgan, 1802), 139–40, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Carl R. Lounsbury, ed., An Illustrated Glossary of Early Southern Architecture and Landscape (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alice B. Lockwood, ed., Gardens of Colony and State: Gardens and Gardeners of the American Colonies and of the Republic before 1840, 2 vols. (New York: Charles Scribner’s for the Garden Club of America, 1931), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Richard Blome, The Present State of His Majesties Isles and Territories in America (London: H. Clark, 1687), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Thomforde, “William Penn’s Estate at Pennsbury and the Plants of Its Kitchen Garden” (MS thesis, Public Horticulture Administration, University of Delaware, 1986), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Pehr Kalm, The America of 1750: Peter Kalm’s Travels in North America. The English Version of 1770, 2 vols. (New York: Wilson-Erickson, 1937), view on Zotero.

- ↑ James Birket, Some Cursory Remarks (Made by James Birket in His Voyage to North America 1750–1751) (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1916), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Mary M. Ambler, “Diary of M. Ambler, 1770,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 45 (April 1937), 152–70, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Philip Vickers Fithian, Journal & Letters of Philip Vickers Fithian, 1773-1774: A Plantation Tutor of the Old Dominion, ed. by Hunter D. Farish (Williamsburg, VA: Colonial Williamsburg, 1943), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Fred Shelley, ed., “The Journal of Ebenezer Hazard in Virginia, 1777,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 62 (1954), 400–23, view on Zotero.

- ↑ George Washington, The Diaries of George Washington, ed. by Donald Jackson and Dorothy Twohig, 6 vols. (Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 1978), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Parker Cutler, Life, Journals, and Correspondence of Rev. Manasseh Cutler, LL.D. (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 1987), [1].

- ↑ Jedidiah Morse, The American Geography; Or, A View of the Present Situation of the United States of America (Elizabeth Town, NJ: Shepard Kollock, 1789), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Karen Madsen, “William Hamilton’s Woodlands,” (paper presented for seminar in American Landscape, 1790–1900, instructed by E. McPeck, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University, 1988), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 William Bartram, Travels through North and South Carolina, Georgia, East and West Florida, ed. Mark Van Doren (New York: Dover, 1928), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Loughton Smith, Journal of William Loughton Smith, 1790-1791, ed. by Albert Matthews (Cambridge, MA: The University Press, 1917), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Timothy Dwight, Travels in New England and New York, 4 vols. (New Haven, CT: Timothy Dwight, 1821), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John C. Ogden, An Excursion into Bethlehem & Nazareth, in Pennsylvania, in the Year 1799 (Philadelphia: Charles Cist, 1800), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Drayton, “The Diary of Charles Drayton I, 1806,” Drayton Papers, MS 0152, Drayton Hall, SC, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Lillian B. Miller et al., eds., The Selected Papers of Charles Willson Peale and His Family, vol. 3, The Belfield Farm Years 1810–1820 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Elbridge Gerry, Jr., The Diary of Elbridge Gerry, Jr. (New York: Brentano’s, 1927), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Lambert, Travels through Canada, and the United States of North America in the Years 1806, 1807, and 1808, 2 vols. (London: Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy, 1816), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Impressions Respecting New Orleans: Diaries and Sketches, 1818–1820, ed. by Samuel Wilson (New York: Columbia University Press, 1951), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Benjamin Silliman, Remarks Made on a Short Tour between Hartford and Quebec, in the Autumn of 1819 (New Haven, CT: S. Converse, 1824), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Martha Ogle Forman, Plantation Life at Rose Hill: The Diaries of Martha Ogle Forman, 1814–1845 (Wilmington, DE: Historical Society of Delaware, 1976),view on Zotero.

- ↑ Robert Waln Jr., “An Account of the Asylum for the Insane, Established by the Society of Friends, near Frankford, in the Vicinity of Philadelphia,” Philadelphia Journal of the Medical and Physical Sciences 1 (new series) (1825), 225–51, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Nina Fletcher Little, American Decorative Wall Painting 1700–1850 (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1972), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Margaret Bayard Smith, The First Forty Years of Washington Society, ed. by Gaillard Hunt (New York: Charles Scribner’s, 1906), view on Zotero.

- ↑ James Boyd, A History of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1827–1927 (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1929), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Cullen Bryant, The Letters of William Cullen Bryant, ed. William Cullen II Bryant and Thomas G. Voss (New York: Fordham University Press, 1975), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Suzanne Turner, Historic Landscape Report: The Landscape at the Shadows-on-the-Teche (New Ibera, LA: Shadows-on-the-Teche, 1993), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Warner Barber and Henry Howe, Historical Collections of the State of New York; Containing a General Collection of the Most Interesting Facts, Traditions, Biographical Sketches, Anecdotes, &c., Relating to Its History and Antiquities, with Geographical Descriptions of Every Township in the State (New York: S. Tuttle, 1841), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas S. Kirkbride, Reports of the Pennsylvania Hospital for The Insane: For the Years 1846–7–8–9 and 50 (Philadelphia: Published by order of the Board of Managers, 1851), view on Zotero.

- ↑ P. B., “Progress of Horticulture in Rochester, N.Y.,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 10, no. 1 (January 1844): 15–19, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas S. Kirkbride, “Description of the Pleasure Grounds and Farm of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, with Remarks,” American Journal of Insanity 4, no. 4 (April 1848): 347–54, view on Zotero.

- ↑ James O. Breeden, ed., Advice Among Masters: The Ideal in Slave Management in the Old South (Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1980), view on Zotero.

- ↑ C. Smith, “Notes on the Culture of Melons at the North,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 6, no. 5 (May 1851): 228–30, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Stephen Switzer, Ichnographia Rustica, or The Nobleman, Gentleman and Gardener’s Recreation . . . , 1st ed., 3 vols. (London: D. Browne, 1718), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Ephraim Chambers, Cyclopaedia, or An Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences. . . ., 5th ed., 2 vols. (London: D. Midwinter et al., 1741), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language: In Which the Words Are Deduced from the Originals and Illustrated in the Different Significations by Examples from the Best Writers, 2 vols. (London: W. Strahan for J. and P. Knapton, 1755), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufacturers and Commerce, The Complete Farmer, or A General Dictionary of Husbandry, 2nd ed. (London: R. Baldwin et al., 1769), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas A. Sheridan, A Complete Dictionary of the English Language, Carefully Revised and Corrected by John Andrews. . . ., 5th ed. (Philadelphia: William Young, 1789), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel Deane, The New-England Farmer, or Georgical Dictionary (Worcester, MA: Isaiah Thomas, 1790), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. B. [John Beale] Bordley, Essays and Notes on Husbandry and Rural Affairs, 2nd ed. (Philadelphia: Thomas Dobson, 1801), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, “Door Yards,” New England Farmer 5, no. 43 (May 18, 1827): 340, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, “Landscape Gardening,” Horticultural Register, and Gardener’s Magazine 3 (April 1, 1837): 121–31, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, “Front Yards,” New England Farmer, and Gardener’s Journal 16, no. 1 (July 12, 1837): 3, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Franklin Farmer, “Front Yards—Shrubbery—Flowers,” Horticultural Register, and Gardener’s Magazine 4 (April 1, 1838): 136–39, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Edward James Hooper, The Practical Farmer, Gardener and Housewife, or Dictionary of Agriculture, Horticulture, and Domestic Economy (Cincinnati, Ohio: George Conclin, 1842), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William H. Ranlett, The Architect, 2 vols. (1849–51; repr., New York: Da Capo, 1976), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. Downing, “On the Drapery of Cottages and Gardens,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 3, no. 8 (February 1849): 353–59, view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses; Including Designs for Cottages, Farm-Houses, and Villas (1850; repr., New York; Da Capo, 1968), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 Sotheby’s New York, Important American Schoolgirl Embroideries (January 2012), view on Zotero.