Difference between revisions of "Mount Vernon"

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

[[George Washington|Washington]] also maintained a [[botanic garden|botanical garden]], located near the upper garden and behind the spinning house, where he experimented with growing rare and delicate seeds and plants—many of which he received as gifts from friends—until they were strong enough to transplant to other areas of his estate ([[#GW_1786|view text]]). <span id="Chastellux_cite">On the south side of the [[bowling green]], the lower garden served as the kitchen garden. To the south of the lower garden was the so-called Vineyard Enclosure, named for the failed grape-growing experiments that Washington conducted there ([[#Chastellux|view text]]). By the mid-1780s, the Vineyard Enclosure contained other plant materials, including trees, grasses, and grains as well as a “fruit garden.”<ref>Pogue 1996, 60–65, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/76S2DCKP view on Zotero].</ref> | [[George Washington|Washington]] also maintained a [[botanic garden|botanical garden]], located near the upper garden and behind the spinning house, where he experimented with growing rare and delicate seeds and plants—many of which he received as gifts from friends—until they were strong enough to transplant to other areas of his estate ([[#GW_1786|view text]]). <span id="Chastellux_cite">On the south side of the [[bowling green]], the lower garden served as the kitchen garden. To the south of the lower garden was the so-called Vineyard Enclosure, named for the failed grape-growing experiments that Washington conducted there ([[#Chastellux|view text]]). By the mid-1780s, the Vineyard Enclosure contained other plant materials, including trees, grasses, and grains as well as a “fruit garden.”<ref>Pogue 1996, 60–65, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/76S2DCKP view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| − | + | Much as he had during his first period of extended absence, [[George Washington|Washington]] remained active in the cultivation of his gardens while away from from Mount Vernon between 1789 and 1797 to serve as the first United States president. In March 1792 [[George Washington|Washington]] sent to Mount Vernon from Philadelphia more than thirty species obtained from [[William Hamilton|William Hamilton’s]] [[The Woodlands|Woodlands]] estate and specimens of more than one hundred species that he purchased from [[Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery]]. He also required that his gardener and farm manager send weekly updates to Philadelphia from Mount Vernon every Wednesday, reporting on the tasks accomplished each week and the amount of time spent on each task.<ref>Many of the plants sent from Bartram’s died upon arrival and were replaced with an additional shipment in November. For lists of the plants that Washington obtained from Bartram and Hamilton, see Erby 2015, “Gardens and Groves,” 143–155, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/ZAVXZPMS view on Zotero].</ref> | |

[[Image:0088.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 5, Benjamin Henry Latrobe, "View to the North from the Lawn at Mount Vernon," 1796.]] | [[Image:0088.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 5, Benjamin Henry Latrobe, "View to the North from the Lawn at Mount Vernon," 1796.]] | ||

Revision as of 18:27, August 3, 2017

Mount Vernon, located in Fairfax County, Virginia, was the plantation home of the first president of the United States, George Washington (1732–1799), who made significant alterations to the mansion house and grounds throughout the late eighteenth century. The estate was especially well known for its greenhouse, gardens, and unusual two-story portico overlooking the Potomac River. Today, Mount Vernon is operated as a historic site by the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association.

Overview

Alternate Names: Little Hunting Creek Plantation (before 1743)

Site Dates: Established 1674

Site Owner(s): John Washington (c. 1631–1677), Lawrence Washington (1659–1698), Mildred Washington (c. 1697–1747), Augustine Washington (1694–1743), Lawrence Washington (1718–1752), Ann Fairfax Washington Lee (1728–1761), George Washington (1732–1799), Bushrod Washington (1762–1829), John Augustine Washington II (1789–1832), Jane Charlotte Blackburn Washington (1786–1855), John Augustine Washington III (1821–1861), Mount Vernon Ladies' Association

Associated People: Philip Bateman (gardener from 1773–1789), David Cowan (gardener from 1773–1774), Lund Washington (estate manager), George Augustine Washington (farm manager), Johann Christian Ehlers (gardener from 1789–1797), Anthony Whiting (estate manager from 1790–1793), John Gottleib Richter (gardener from 1793–1796), William Spence (gardener from 1797–c. 1800)

Location: Alexandria, Va.

View on Google maps

History

When George Washington began leasing Mount Vernon, his family’s estate on the banks of the Potomac River in Fairfax County, Virginia, from his elder half-brother’s widow in 1754, it comprised approximately 2,100 acres and a modest, one-and-a-half story dwelling.[1] Shortly after taking up residence, Washington made significant improvements to the property. From 1757–1759 he added an additional story to the house as well as what he called a "rusticated" wooden exterior that was made of beveled pine boards coated with paint and sand or pulverized stone (in a process Washington called “sanding”) to imitate the appearance of stone blocks.[2] This first round of renovations was largely complete by the time Washington married Martha Dandridge Custis (1731–1802), a wealthy widow, in 1759. He acquired additional property after officially inheriting Mount Vernon in 1761 and divided the land into five farms—Mansion House, Dogue Run, Muddy Hole, Union, and River farms—which together totaled more than 8,000 acres [Fig. 1]. By the early 1770s, Washington oversaw a prosperous and diversified plantation as well as a herring and shad fishery at Mount Vernon. He relied on enslaved labor to maintain these large operations and to complete much of the construction and landscaping of his estate.[3]

Washington commenced a second round of renovations to the house in 1773, turning the structure into a much larger mansion topped with a cupola, and adding a portico to the west façade and arcaded wings to the north and south that connected the mansion to various dependencies. He also landscaped the surrounding grounds to complement the new architectural design. The arcaded wings opened up views of the landscape so that visitors could glimpse the Potomac River when looking east through the columns from the west side of the mansion, or see the groves of trees when looking west from the east lawn.[4] He transplanted native trees from other sites on his property to create two new groves near the mansion on the north and south sides of the house. When Washington was away from Mount Vernon between 1774 and 1783, while serving as a Virginia delegate to the Continental Congress and commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, much of the construction and landscaping was carried out, according to his specifications, by his cousin and estate manager, Lund Washington. Even in the midst of the American Revolution, Washington maintained a strong interest in the ongoing improvements at Mount Vernon. He wrote to Lund Washington on August 19, 1776, from New York, during the siege of the city, instructing him to plant locust trees in the northern grove and “all the clever kind of Trees (especially flowering ones)” in the southern grove (view text).

Washington significantly redesigned the gardens at Mount Vernon in 1784, after the conclusion of the American Revolution and during a period of brief respite from public duties. While implementing the plan between 1785 and 1787, he relied on the labor of both free and enslaved workers to transplant trees, build walls, and gravel paths.[5] Although many trees were transplanted from other parts of his plantation (view text), he also imported trees from places such as South Carolina and New York. In 1785 he wrote to a nephew who resided in South Carolina to request “acorns of the live Oak—and the Seeds of the Ever-green Magnolia,” which Washington planted at Mount Vernon in April 1786 (view text).[6] During this period, Washington also completely redesigned the overland, western approach to the mansion—the route used by most visitors to reach the estate—so that, after traveling through a dense wood for several miles, visitors reached an opening, staked out by Washington in 1785, that created a dramatic vista onto the bowling green and mansion (view text).[7]

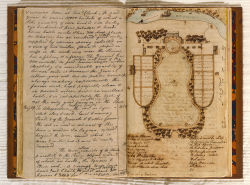

Washington’s style was idiosyncratic. One late-eighteenth-century visitor to the estate apparently noticed that the gardens at Mount Vernon did not fit neatly within a single style, remarking that they were “laid out somewhat according to the form of English gardens” (view text). On the one hand, the updated design—with naturalistic features such as shaded, serpentine paths and sweeping lawns—reflected his knowledge of fashionable English gardens and the influence of English gardening texts, especially Batty Langley’s (1696–1751) New Principles of Gardening (London, 1728) and Philip Miller’s (1691–1771) Abridgement of the Gardener’s Dictionary (London, 1763).[8] On the other hand, Washington retained some of the symmetrical and geometric elements that had been more popular in American gardens during the colonial period. The symmetrically arranged bowling green and plantings of trees and shrubberies, for example, was a central feature of the landscape on the west side of the mansion, as indicated by this 1787 sketch of the pleasure grounds made by the British merchant Samuel Vaughan (1720–1802) [Fig. 2].[9]

During this period, Washington also updated the so-called upper and lower gardens located to the northwest and southwest of the mansion, changing the preexisting rectangular gardens into a shape resembling a pointed arch, with bowed perimeters that complemented the curvilinear forms of the serpentine paths nearby. The upper garden, located on the north side of the bowling green, was usually a guest’s first stop when visiting Mount Vernon. It was divided into six rectangular beds that were separated by gravel paths and arranged symmetrically. In the centers of the three main planting beds, which were edged with dwarf boxwood and flowering shrubs, Washington grew vegetables and fruit for the household. Another planting bed contained a formal boxwood parterre in the shape of Fleur de Lis, which was by then already an old-fashioned garden style, as Benjamin Latrobe noted (view text). Other beds were filled with flowering trees, bushes, and flowers, and espaliered fruit trees grew against the upper garden’s brick wall perimeter.[10]

In the upper garden’s greenhouse, Washington’s gardeners cultivated exotic tropical plants, ranging from citrus trees to aloe vera and sago palm. Washington began planning the structure in 1784, at a time when greenhouses were not yet common in British North American gardens. He had seen greenhouses during his travels but was uncertain about how to construct one, and he wrote to his friend Tench Tilghman (1744–1786) in August 1784 asking for the specifications of Margaret Tilghman Carroll’s (1742–1817) greenhouse at Mount Clare, her estate outside of Baltimore (view text). Upon completion of the main section of the greenhouse in 1787, Washington sought a gardener who had experience raising tropical plants and the knowledge to operate the structure’s subterranean heating system. Through the recommendation of a friend, he hired the German gardener Johann (John) Christian Ehlers, who immigrated to the United States in 1789 specifically to work at Mount Vernon and was employed by Washington until 1797. Washington next hired the Scottish gardener William Spence, who worked at Mount Vernon until shortly after Washington’s death in 1799.[11]

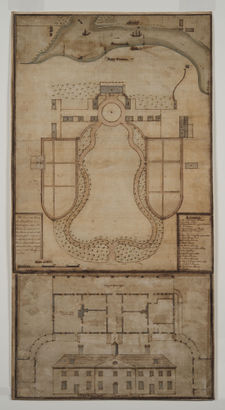

In 1792 Washington added wings—each comprising two rooms with sleeping berths—on the east and west sides of the greenhouse to house up to eighty enslaved people who worked at the Mansion House Farm. A fire on December 16, 1835, destroyed Washington’s greenhouse and slave quarters, but their appearance is recorded in this 1805 insurance drawing [Fig. 3], which, in addition to other drawings and archaeological evidence, served as the basis for the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association’s 1951 reconstruction of the building that stands today. The central section of the greenhouse opened up to the pleasure gardens at the south, while the slave quarters opened up to the service lane to the north, an arrangement designed to maintain racialized social hierarchies by controlling access to the landscape. The bowling green was reserved for the Washington family and their guests [Fig. 4], and Washington once instructed that enslaved children be kept away from playing in the area.[12]

Washington also maintained a botanical garden, located near the upper garden and behind the spinning house, where he experimented with growing rare and delicate seeds and plants—many of which he received as gifts from friends—until they were strong enough to transplant to other areas of his estate (view text). On the south side of the bowling green, the lower garden served as the kitchen garden. To the south of the lower garden was the so-called Vineyard Enclosure, named for the failed grape-growing experiments that Washington conducted there (view text). By the mid-1780s, the Vineyard Enclosure contained other plant materials, including trees, grasses, and grains as well as a “fruit garden.”[13]

Much as he had during his first period of extended absence, Washington remained active in the cultivation of his gardens while away from from Mount Vernon between 1789 and 1797 to serve as the first United States president. In March 1792 Washington sent to Mount Vernon from Philadelphia more than thirty species obtained from William Hamilton’s Woodlands estate and specimens of more than one hundred species that he purchased from Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery. He also required that his gardener and farm manager send weekly updates to Philadelphia from Mount Vernon every Wednesday, reporting on the tasks accomplished each week and the amount of time spent on each task.[14]

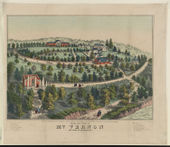

For many eighteenth- and nineteenth-century visitors to Mount Vernon, the view from the large portico on the east façade of the mansion, overlooking a lawn that sloped down towards the Potomac River, was the most striking aspect of Washington’s landscape design [Fig. 5]. The Polish nobleman Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz (1758—1841), who visited Mount Vernon in June 1798, recorded in his journal that he thought the portico afforded “perhaps the most beautiful view in the world” view text). Facing the river, late eighteenth-century visitors would have been able to see Washington’s locust grove to the left and the broad, sweeping lawn that led to the riverbank before them. Joseph Manca has argued that Washington planted a few isolated trees on the brow of the hill to increase the sense of distance between the portico and the water.[15] Just below the crest of the hill, Washington built a ha-ha, and he intended to create a gravel walk along the river’s edge with a fishpond nearby, but these features were never installed.[16]

In 1785 Washington added a deer park and icehouse to sections of the east lawn that were not easily visible from the portico. He fenced off approximately eighteen acres of the east slope to create the deer park, which he stocked with both American and English deer [Fig. 6]. The park fell into disrepair while Washington was serving as president in Philadelphia. Once the deer broke out of the fence, they were permitted to roam freely throughout the estate view text). On the far edge of the east lawn, a small but elaborate icehouse, constructed of brick and wood with a vaulted interior and pediment over the door, was built between the mansion and the river (the source of the ice). In the early nineteenth century, Washington’s nephew Bushrod Washington, who inherited Mount Vernon after the deaths of George and Martha Washington, reduced the size of the icehouse and constructed a summerhouse on the site, as seen at the center of Victor de Grailly’s mid-nineteenth-century painting of Washington’s tomb [Fig. 7].[17]

George Washington died at Mount Vernon in December 14, 1799, and Martha Washington continued to reside at the estate until her own death in 1802. Bushrod Washington owned it until the time of his death in 1829. In the area of the upper garden, he added a rammed-earth greenhouse as well as a brick hothouse and pinery (to cultivate pineapples) adjacent to his uncle’s greenhouse and slave quarters. Like Washington’s original structures, Bushrod Washington’s additions were badly damaged in the 1835 fire. George Washington’s will instructed that a new brick family tomb should be constructed at the foot of the Vineyard Enclosure to replace the existing—and badly decayed—family vault. Washington’s descendants relocated George and Martha Washington’s remains, as well as those of other members of the family, from the so-called Old Tomb to the New Tomb in 1831, in accordance with Washington’s wishes. Mount Vernon gradually fell into disrepair after Bushrod Washington’s death, but it remained in the possession of the Washington family until 1858, when John Augustine Washington III, George Washington’s great-grand-nephew, sold the mansion and two-hundred acres of the property to the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association. The organization took formal possession of the estate in February 1860 and continues to operate it as a historic site today.[18]

--Lacey Baradel

Texts

- Washington, George, August 19, 1776, in a letter to Lund Washington[19] back up to history

- "Plant Trees in the room of all dead ones in proper time this Fall. and as I mean to have groves of Trees at each end of the dwelling House, that at the South end to range in a line from the South East Corner to Colo. Fairfax’s, extending as low as another line from the Stable to the dry well, and towards the Coach House, Hen House, & Smoak House as far as it can go for a Lane to be left for Carriages to pass to, & from the Stable and Wharf. from the No. Et Corner of the other end of the House to range so as to Shew the Barn &ca. in the Neck—from the point where the old Barn used to Stand to the No. Et Corner of the Smiths Shop, & from thence to the Servants Hall, leaveng a passage between the Quarter & Shop, and so East of the Spinning & Weaving House (as they used to be called) up to a Wood pile, & so into the yard between the Servts Hall & the House newly erected—these Trees to be Planted without any order or regularity (but pretty thick, as they can at any time be thin’d) and to consist that at the North end, of locusts altogether. & that at the South, of all the clever kind of Trees (especially flowering ones) that can be got, such as Crab apple, Poplar, Dogwood, Sasafras, Lawrel, Willow (especially yellow & Weeping Willow, twigs of which may be got from Philadelphia) and many others which I do not recollect at present—these to be interspersed here and there with ever greens such as Holly, Pine, and Cedar, also Ivy—to these may be added the Wild flowering Shrubs of the larger kind, such as the fringe Tree & several other kinds that might be mentioned."

- Washington, George, December 25, 1782 (quoted in Johnson 1953: 87–88)[20]

- "I wish that the afore-mentioned shrubs and ornamental and curious trees may be planted at both ends that I may determine hereafter from circumstances and appearances which shall be the grove and which the wilderness. It is easy to extirpate Trees from any spot but time only can bring them to maturity."

- Washington, George, January 15, 1784, in a letter to William Hamilton[21]

- "If I recollect right, I heard you say when I had the pleasure of seeing you in Philadelphia, that you were about a Floor composed of a Cement which was to answer the purpose of Flagstones or Tiles, and that you proposed to variegate the colour of the squares in the manner of the former.

- "As I have a long open Gallery in Front of my House to which I want to give a Stone, or some other kind of Floor which will stand the weather; I would thank you for information respecting the Success of your experiment—with such directions and observations (if you think the method will answer) as would enable me to execute my purpose. If any of the component parts are scarce & expensive, please to note it, & where they are to be obtained—& whether all seasons will do for the admixture of the Composition."

- Washington, George, August 11, 1784, in a letter to Tench Tilghman[22] back up to history

- "I shall essay the finishing of my Green Ho. this fall; but find that neither my own knowledge, or that of any person abt me, is competent to the business.

- "Shall I, for this reason, ask the favor of you to give me a short detail of the internal construction of the Green House at Mrs Carrolls?

- "I am perswaded now, that I planned mine upon too contracted a Scale—My House is (of Brick) 40 feet by 24 in the outer dimensions—& half the width is disposed of for two rooms back of the part designed for the Green House; leaving not more than about 37 by 10 in the clear for the latter. As there is no cover on the walls yet, I can raise them to any height."

- Washington, George, January 12, 1785, diary entry (Fitzpatrick, ed., 1925: 2: 334)[23] back up to history

- "Road to my Mill Swamp, where my Dogue run hands were at Work, and to other places in search of the sort of Trees I shall want for my Walks, groves, and Wildernesses."

- Washington, George, 1785, diary entries (Jackson and Twohig, eds., 1978: 4:86, 89, 94, 96, 97, 99, 101, 107, 161, 199, 215)[24]

- "[8 February] Finding that I should be very late in preparing my Walks & Shrubberies if I waited till the ground should be uncovered by the dissolution of the Snow—I had it removed Where necessary & began to Wheel dirt into the Ha! Haws &ca.—tho' it was it exceeding miry & bad working. . . .

- "[12 February] Planted Eight young Pair Trees sent me by Doctr. Craik in the following places. . . .

- "3 Brown Beuries in the west square in the Second flat—viz. 1 on the border (middle thereof) next the Fall or slope—the other two on the border above the walk next the old Stone Wall....

- "[22 February] I also removed from the Woods and old fields, several young Trees of Sassafras, Dogwood, & red bud, to the Shrubbery on the No. Side the grass plat. . . .

- "[28 February] Planted all the Mulberry trees, Maple trees, & Black gums in my Serpentine walks and the Poplars on the right walk—the Sap of which and the Mulberry appeared to be moving. Also planted 4 trees from H. Hole the name unknown but of a brittle wood which has the smell of Mulberry. . . .

- "[2 March] Planted the remainder of the Ash Trees—in the Serpentine walks—the remainder of the fringe trees in the Shrubberies—all the black haws—all the large berried thorns with a small berried one in the middle of each clump—6 small berried thorns with a large one in the middle of each clump—all the swamp red berry bushes & one clump of locust trees. . . .

- "[3 March] Planted the remainder of the Locusts—Sassafras—small berried thorn & yellow Willow in the Shrubberies, as also the red buds— a honey locust and service tree by the South Garden House. Likewise took up the clump of Lilacs that stood at the Corner of the South Grass plat & transplanted them to the clusters in the Shrubberies & standards at the south Garden gate. The Althea trees were also planted. . . .

- "Employed myself the greatest part of the day in pruning and shaping the young plantation of Trees & Shrubs. . . .

- "[7 March] Planted all my Cedars, all my Papaw, and two Honey locust Trees in my Shrubberies and two of the latter in my groves—one at each (side) of the House and a large Holly tree on the Point going to the Sein landing. . . .

- "Finished Plowing the Ground adjoining the Pine Grove, designed for Clover & Orchard grass Seed. . . .

- "[11 March] Planted . . . 13 Yellow Willow trees alternately along the Post and Rail fence from the Kitchen to the South ha-haw and from the Servants' Hall to the Smith's Shop....

- "[24 March] Finding the Trees round the Walks in my wildernesses rather too thin I doubled them by putting (other Pine) trees between each.

- "[8 July] Sowed one half the Chinese Seed given me by Mr. Porter and Doctr. Craik, in three rows in the Section next the Quarter (in my Botanical garden) beginning in that part next the garden Wall, and at the end next the Middle Walk. . . .

- "[30 September] Began again to Smooth the Face of the Lawn, or Bolling Green on the West front of my House—what I had done before the Rains, proving abortive. . . .

- "[28 October] Finished levelling and Sowing the lawn in front of the Ho[use] intended for a Bolling Green—as far as the Garden Houses."

- Washington, George, February 28, 1785, in a letter to Henry Knox[25]

- "...I perceive, & was most interested by something which was said respecting the composition for a public walk. . . . Now, as I am engaged in works of this kind, I would thank you, if there is any art in the preparation, to communicate it to me—whether designed for Carriages, or walking. My Gardens have gravel walks (as you possibly may recollect) in the usual Style, but if a better composition has been discovered for these, I should gladly adopt it. the matter however which I wish principally to be informed in, is, whether your walks are designed for Carriages, and if so, how they are prepared, to resist the impression of the wheels. I am making a Serpentine road to my door, & have doubts (which it may be in your power to remove) whether any thing short of solid pavement will answer."

- Chastellux, François-Jean de, December 12, 1785, in a letter to George Washington[26] back up to history

- "What satisfaction should it be for me, if I was walking upon your bowlingreen, to look upon the Potomack, and endeavour with the help of a Telescope to distinguish, whether the aproaching vessel wears the american, the french or the brittish colours; to say: ’tis a brittish ⟨illegible⟩ who comes and fetch tabacco; then continue quietly our walk and go towards the grove to observe the growth of your trees, even of your vineyard, that a french man can, I dare say, examine without jealousy; for, my dear general, you can sow and reap laurels, but grapes and wine are not within the compass of your powers: do not be angry, dear general: foreigners have been always welcome at your house, and black billy is an exceeding good gentleman usher for madeyra, champain, and Burgundy’s ⟨travellers⟩."

- Washington, George, 1786, diary entries (Jackson and Twohig, eds., 1978: 4:267, 293, 304, 308, 350)[24] back up to history

- "[25 January] And set about the Banks round the Lawn, in front of the gate between the two Mounds of Earth. . . .

- "[13 March] The ground being in order for it, I set the people to raising and forming the mounds of Earth by the gate in order to plant weeping willow thereon....

- "[6 April] Transplanted 46 of the large Magnolio of So. Carolina from the box brought by G. A. Washington last year—viz.—6 at the head of each of the Serpentine Walks next the Circle—26 in the Shrubbery or grove at the South end of the House & 8 in that at the No. end. The ground was so wet, more could not at this time be planted there....

- "[11 April] In the Section in my botanical garden, next the House nearest the circle, I planted 4 Rows of the laurel berries in the grd. where, last year I had planted the Physic nuts &ca.—now dead & next to these in the same section are [ ] rows of the pride of China. The Rows of both these kinds are 16 inches asunder & the Seeds 6 inches apart in the Rows. . . .

- "[19 June] A Monsr. Andri Michaux—a Botanest sent by the Court of France to America (after having been only 6 Weeks returned from India) came in a little before dinner with letters of Introduction & recommendation from the Duke de Lauzen, & Marqs. de la Fayette to me. He dined and returned afterwards to Alexandria on his way to New York, from whence he had come; and where he was about to establish a Botanical garden."

- Vaughan, Samuel, 1787 (quoted in Norton and Schrage-Norton 1985: 142)[27]

- “Before the front of the house . . . there are lawns, surrounded with gravel walks 19 feet wide. with trees on each side the larger, for shade. outside the walks trees & shrubberies. Parralel [sic] to each exterior side a Kitchen Gardens. with a stately hot house on one side.”

- Washington, George, November 12, 1787, in a letter to Samuel Vaughan[28] back up to history

- "The letter without date, with which you were pleased to honor me, accompanied by a plan of this Seat, came to my hands by the last Post—for both I pray you to accept my sincere and hearty thanks.

- "The plan describes with accuracy the houses, walks, shrubs beries &ca except in the front of the Lawn—west of the Ct yard. There the plan differs from the original—in the former, you have closed the prospect with trees along the walk to the gate—whereas in the latter the trees terminate with two mounds of earth one on each side on which grow Weeping Willows leaving an open and full view of the distant woods—the mounds are at 60 yards apart. I mention this because it is the only departure from the origl." [Fig. x]

- Brissot de Warville, J.P., 1788 (1919: 254)[29]

- "I hastened to arrive at Mount Vernon, the seat of General Washington, ten miles below Alexandria on the same river. On this rout you traverse a considerable wood, and after having passed over two hills, you discover a country house of an elegant and majestic simplicity. It is preceded by grass plats; on one side of the avenue are the stables, on the other a green-house, and houses for a number of negroe mechanics. In a spacious back yard are turkies, geese, and other poultry. This house overlooks the Potowmack, enjoys an extensive prospect, has a vast and elevated portico on the front next to the river, and a convenient distribution of the apartments within."

- Enys, Lt. John, February 12, 1788 (Cometti, ed., 1976: 246)[30]

- "From hence is one of the most delightfull Prospects I ever beheld. It had the Command of a View each way of some Miles up and down the River Potowmack whch [sic] is here about two Miles broad On which during the Summer there are constantly ships moving. The Hills arrownd it are coverd with plantations some of which have Elegant houses standing on them all of which being situated on Eminences form very beautifull Objects for each other."

- Humphreys, David, c. 1788–1789, describing Mount Vernon (quoted in Manca 2012: 84–85)[31] back up to history

- "The area of the Mount, is 200 feet above the surface of the water, and after furnishing a lawn of 5 acres in front & about the same in rear of the buildings, falls off rather abruptly on those quarters. On the north-end it subsides gradually into extensive pasture grounds; while on the south it slopes more steeply in a shorter distance, and terminates with the coach-house, stables, vineyard & nurseries. On either wing is a dense & opaque grove of different flowering forest trees. Parellel [sic] with them, on the land-side, are two spacious gardens, into which one is led by the two serpentine gravel-walks, planted with weeping willows & umbrageous shrubs. The Mansion House itself, though much embellished by yet not perfectly satisfactory to the chaste taste of the present Possessor, appears venerable & convenient. The superb banquetting room has been finished since he returned home from the army. A lofty Portico, 96 feet in length, supported by eight pillars, has a pleasing effect when viewed from the water; and the tout ensemble, of the green-house, schoolhouse, offices & servants-hall, when seen from the countryside, bears a resemblance to a rural village: especially as the lands in that site are laid out somewhat according to the form of English gardens, in meadows & grass-grounds, ornamented with little copses, circular clumps & single trees. [O]n the opposite side of a little creek to the Northward, an extensive plain, exhibiting cornfields & cattle grazing, affords in summer a luxurus landscape to the eye; While the cultivation declivities, intermingle with woodlands on the Maryland shore concludes the prospect; While to blended verdure of woodlands & cultivated declivities on the Maryland shore variegates the prospecton another side in a charming manner. A small Park on the margin of the river, where the English fallow-deer & the American wild-deer are seen through the thickets, alternately with the vessels as they are sailing along, adds a romantic & picturesque appearance to the whole scenery. Such are the philosophic shades, to which the late Commander in Chief of the American armies has retired, from the tumultuous scenes of a busy world."

- Weld, Isaac, December 1795, describing Mount Vernon (1799: 1: 90–95)[32]

- "Very thick woods remain standing within four or five miles of the place; the roads through them are very bad, and so many of them cross one another in different directions, that it is a matter of very great difficulty to find the right one. . . .

- "The Mount is a very high part of the bank of the river, which rises very abruptly about two hundred feet above the level of the water. The river before it is three miles wide, and on the opposite side it forms a bay about the same breadth, which extends for a considerable distance up the country. This, at first sight, appears to be a continuation of the river; but the Patowmac takes a very sudden turn to the left, two or three miles above the house, and is quickly lost to the view. Downwards, to the right, there is a prospect of it for twelve miles. The Maryland shore, on the opposite side, is beautifully diversified with hills, which are mostly covered with wood; in many places, however, little patches of cultivated ground appear, ornamented with houses. The scenery altogether is most delightful. The house, which stands about sixty yards from the edge of the Mount, is of wood, cut and painted so as to resemble hewn stone. The rear is towards the river, at which side is a portico of ninety-six feet in length, supported by eight pillars. The front is uniform, and at a distance looks tolerably well. The dwelling house is in the center, and communicates with the wings on either side, by means of covered ways, running in a curved direction. Behind these wings, on the one side, are the different offices belonging to the house, and also to the farm, and on the other, the cabins for the SLAVES. In front, the breadth of the whole building, is a lawn with a gravel walk round it, planted with trees, and separated by hedges on either side from the farm yard and garden. As for the garden, it wears exactly the appearance of a nursery, and with every thing about the place indicates that more attention is paid to profit than to pleasure. The ground in the rear of the house is also laid out in a lawn, and the declivity of the Mount, towards the water, in a deer park. . . .

- "As almost every stranger going through the country makes a point of visiting Mount Vernon, a person is kept at the house during General Washington's absence, whose sold business is to attend to strangers. Immediately on our arrival every care was taken of our horses, beds were prepared, and an excellent supper provided for us, with claret and other wine, &c."

- Washington, George, June 5, 1796, in a letter to William Pearce, estate manager of Mount Vernon[33]

- "In a few days after we get there, we shall be visited, I expect, by characters of distinction; I could wish therefore that the Gardens, Lawns, and every thing else, in, and about the Houses, may be got in clean & nice order. If the Gardener needs aid, to accomplish as much of this as lyes within his line, let him have it; & let others rake, & scrape up all the trash, of every sort & kind about the houses, & in holes & corners and throw it (all I mean that will make dung) into the Stercorary and the rest into the gullied parts of the road, coming up to the House—And as the front gate of the Lawn (by the Ivies) is racked, and scarcely to be opened, I wish you would order a new one (like the old one) to be immediately made—and that, with the new ones you have just got made, and all the boarding of every kind that was white before, to be painted white again. If Neal and my own people cannot make the front gate, abovementioned, get some one from Alexandria to do it—provided he will set about & finish it immediately. This must be the way up to the House.

- ". . . . Tell the Gardener, I shall expect every thing that a Garden ought to produce, in the most ample manner. . . .

- "I have no doubt but that you will endeavor so to arrange matters, as to keep your grain, & Hay harvests from interfering as much as possible with each other; and this too without either suffering, by standing too long, if it can possibly be avoided. Begin the former as soon as it can be cut without loss."

- Latrobe, Benjamin Henry, July 19, 1796 (1977: 1:163–165)[34] back up to history

- "The general plan of the building is as at Mr. Man Pages at Mansfield near Fredericsburg, of the old School. . . . The center is an old house to which a good dining room has been added at the North end, and a study &c. &c., at the South. The House is connected with the Kitchen offices by arcade. . . . Along the other front is a portico supported by 8 square pillars, of good proportions and effect...The ground on the West front of the house is laid out in a level lawn bounded on each side with a wide but extremely formal serpentine walk, shaded by weeping Willows. . . . On one side of this lawn is a plain Kitchen garden, on the other a neat flower garden laid out in squares, and boxed with great precission. Along the North Wall of this Garden is a plain Greenhouse. The Plants were arranged in front, and contained nothing very rare, nor were they numerous. For the first time again since I left Germany, I saw here a parterre, chipped and trimmed with infinite care into the form of a richly flourished Fleur de Lis: The expiring groans I hope of our Grandfather's pedantry."

- Washington, George, May 16, 1798, in a letter to Sarah Cary Fairfax[35]

- "Before the War, & even while it existed, altho' I was eight years from home at one stretch, (except the en passant visits made to it on my March to and from the Siege of Yorktown) I made considerable additions to my dwelling house, & alterations in my Offices, & Gardens; but the dilapidati(on) occasioned by time, & those neglects which are co-extensive with the absence of Proprietors, have occupied as much of my time, within the last twelve months in repairing them, as to any former period in the same space."

- Niemcewicz, Julian Ursyn, June 1798, journal entry describing Mount Vernon (1965: 95–102, 104)[36] back up to history

- [June 2] "We continued through the country scored with ravines and well wooded. After 7 miles of road we arrived at the foot of a hill where the properties of Gl. Washington begin. We took a road newly cut through a forest of oaks. Soon we discovered still another hill at the top of which stood a rather spacious house, surmounted by a small cupola, with mezzanines and with blinds painted green. It is surrounded by a ditch in brick with very pretty little turrets at the corners; these are nothing but outhouses. Two bowling greens, a circular one very near the house, the other very large and irregular, form the courtyard in front of the house. All kinds of trees, bushes, flowering plants, ornament the two sides of the court. near the two ends of the house are planted two groves of acacia, called here locust, a charming tree, with a smooth trunk and without branches leaving a clear and open space for the movement of its small and trembling leaves. The ground where they are planted is a green carpet of the most beautiful velvet. This tree keeps off all kinds of insects. There were also a few catalpa and tulip trees there etc.

- "We entered into the house . . . .

- "One enters into a hall which divides the house into two and leads to the piazza. . . . At the right, on entering, is a parlor. . . .

- "From this room one goes into a large salon that the Gl. has recently added. It is the most magnificent room in the house. . . . At the side of the first room is yet another parlor, decorated with beautiful engravings representing storms and seascapes. . . . On the other side of the hall are the dining room, a bedroom, and the library of the Gl; above, several apartments for Madame, Miss Custis and guests. They are all very neatly and prettily furnished.

- "On the side opposite the front is an immense open portico supported by eight pillars. It is from there that one looks out on perhaps the most beautiful view in the world. One sees there the waters of the Potomak rolling majestically over a distance of 4 to 5 miles. Boats which go to and fro make a picture of unceasing motion. A lawn of the most beautiful green leads to a steep slope, covered as far as the bank by a very thick wood where formerly there were deer and roebuck, but a short time ago they broke the enclosure and escaped. . . . It is there that in the afternoon and evening the Gl, his family and the gustes [guests] go to sit and enjoy the fine weather and the beautiful view. I enjoyed it more than anyone. I found the situation of Mount Vernon from this side very similar to that of Pulawy. The opposite bank, the course of the river, the dense woods all combined to enhance this sweet illusion. What a remembrance! . . . .

- "After dinner one goes out onto the portico to read the newspaper. In the evening Gl. Wash[ington] showed us his garden. It is well cultivated and neatly kept; the gardener is an Englishman. One sees there all the vegetables for the kitchen, Corrents, Rasberys, Strawberys, Gusberys, quantities of peaches and cherries, much inferior to ours, which the robins, blackbirds and Negroes devour before they are ripe.

- "Opium, some poppies. . . .

- "One sees also in the garden lilies, roses, pinks, etc. The path which runs all around the bowling green is planted with a thousand kinds of trees, plants and bushes; crowning them are two immense Spanish chestnuts that Gl. Wash[ington] planted himself; they are very bushy and of the greatest beauty. The tree of the tulip, called here Poplar, or Tulip Tree, is very high with a beautiful leaf and the flower in a bell resembling a Tulip, white with a touch of orange at the base. The magnolia [is] a charming tree...with a whitish and smooth trunk; the leaf resembles that of the orange; in bud the flower is like a white acorn which opens out and gives off an odor less strong than the orange but just as agreeable; the fruit is a little cone with crimson seeds; these seeds are held to the cone by small threads. The Sweet Scented Shroub, a shrub which grows in a thicket, with a very deep purple, nearly black flower, has a fragrance which from my point of view surpasses all the others. . . . The superb catalpa was not yet in flower. The fir of Nova Scotia, Spruce Tree, is of a beautiful deep green; it is from their cones that the essence of Spruce is extracted to mix it with the beer. [There was] a tree [blank] bearing thousands and thousands of pods like little pea pods. A thousand other bushes, for the most part species of laurel and thorn, all covered with flowers of different colors, all planted in a manner to produce the most beautiful hues. The weeping willows are deprived of their greatest beauty Last winter there was such a great amount of snow that their branches, not being able to support it, broke. . . . In a word the garden, the plantations, the house, the whole upkeep, proves that a man born with natural taste can divine the beautiful without having seen the model. The Gl. has never left America. After seeing his house and his gardens one would say that he had seen the most beautiful examples in England of this style.

- [June 3] "I went out for a walk with Mr. Law. he showed me a hill covered with old chestnuts, oaks, weeping willows, cedars, etc. It was a burial ground. . . . The sun was setting behind the bluish hills and thick forests of oak and laurel, its rays falling obliquely on the smooth waters of the Potowmak.

- [June 4] "We left on horseback with Mr. Law to see the Gl.'s farm. Mount Vernon was already a large property when Gl. Washington inherited it from his half brother of the first marriage. When he married Mrs. Custis, he took with her as dowry 20,000 pounds of the money of Virginia, about 70,000 doll. He bought, with a large part of this money, land at 20 and 30 shlings per acre, between 4 and 5 pounds (today he would not give them up for ten times as much). His lands in Mount Vernon today enclose 10,000 acres in a single unit. . . .

- "This morning we saw vast fields covered with different kinds of grain. One hundred acres in peas alone, much rye which is distilled into whiski, maize, wheat, flax, large meadows sown to lucerne; the soil although for the most part clayey produces, as a result of good cultivation, abundant harvests. All these lands are divided into four farms with a number of Blacks attached to each and a Black overseer over them. The whole is under the supervision of Mr. Anderson, a Scottish farmer.

- "We saw a very large mill built in stone. An American machine invented by Evens (who has published a work on mills) for the aeration of the flour is very ingenious. Beside the different kinds of grain that are ground for the use of the house, and for the nourishment of the Blacks, each year a thousand kegs of wheat flour are ground for export. . . .

- "Just near by is a whiski distillery. Under the supervision of the son of Mr. Anderson, they distill up to 12 thousand gallons a year. . . . If this distillery produces poison for men, it offers in return the most delicate and the most succulent feed for pigs. . . . We saw here and there flocks of sheep. The Gl. has between six and seven hundred. . . .

- "Blacks. We entered one of the huts of the Blacks, for one can not call them by the name of houses. They are more miserable than the most miserable of the cottages of our peasants. The husband and wife sleep on a mean pallet, the children on the ground; a very bad fireplace, some utensils for cooking, but in the middle of this poverty some cups and a teapot. . . . A very small garden planted with vegetables was close by, with 5 or 6 hens, each one leading ten to fifteen chickens. It is the only comfort that is permitted them; for they may not keep either ducks, geese, or pigs. They sell the poultry in Alexandria and procure for themselves a few amenities. . . . Not counting women and children the Gl. has 300 Negroes of whom a large number belong to Mrs. Washington. Mr. Anderson told me that there are only a hundred who work in the fields. They work all week, not having a single day for themselves except for holidays. One sees by that that the conditions of our peasants is infinitely happier. The mulattoes are ordinarily chosen for servants. . . .

- [June 5] "This morning the Gl. had the kindness to go with us on horseback to show us another of his farms. The soil of it was balck, much better looking and more fertile than that of the others. . . . The Gl. showed us a plow of his own invention: in the middle on the axle itself is a hollow cylinder filled with grain; this cylinder is pierced with different holes, according to the size of the grain. As the plow moves ahead, the cylinder turns and the grain falls, the ploughshare having prepared the furrow for it, and a little blade behind then covers it with earth. He then took us to see a barn for threshing the grain. It is an octagonal building; on the first story the floor is made from planed poles three inches wide which do not touch, leaving an empty space between. Grain is placed on them and horses, driven at a trot, trample it; the kernals fall through to the bottom. . . .

- [June 8] "For three years the deer have almost disappeared from the Gl.'s park. When today we discovered three grazing on the grass a little distance from the house, the Gl. suggested to me to look at them close up. We left. He walked very quickly; I could hardly follow him. We maneuvered to force them to leave their retreat and go towards the field, but the maneuver, clever as it was, did not succeed; they plunged into the wood."

- Cutler, Manasseh, January 2, 1802, journal entry describing a visit to Mount Vernon (1888: 2: 55–58)[37]

- "After leaving Alexandria about three miles, we entered a woodland, which continued, with the exception of a few openings of cultivated fields, until we cam within about a quarter of a mile of the mansion-house on Mt. Vernon. As the road goes out of the woods, which consist of tall and beautiful forests, variegated with all the different kinds of trees, native in this part of the country, it passes by a gate, where we leave the road and pass through the gate nearly at right-angles, and enter an open pasture. On passing through the gate, which stands on an eminence, we at once, and very abruptly, come in full view of the house, on the side back from the river. It appears on an eminence, not like a hill, but a level ground, with a pretty deep valley between, covered with woods and bushes of different kinds, which conceal the winding passage from the gate to the house. . . . In this situation the house, with two ranges of small buildings extending in a curved form, from near the corners of the house, till interrupted by the trees, has quite a picturesque appearance, and the effect is much heightened by coming out of a thick wood, and the sudden and unexpected manner in which it is seen. . . .

- "After breakfast we rambled about the house and gardens, which were not in so high a style as I expected to have found them. The house stands on an elevated level, is two stories, high, with a piazza in front, supported by a row of pillars on the side toward the river, and is about five or six rods from a steep bank descending to the edge of the water. The river is wide, and affords a most delightful prospect far distant up and down the stream. as well as beyond the opposite shore. But the whole country appears to be an extended woods, with very few houses or cultivated fields in any direction. In front of the house is a grass plot, with trees on each side, and inclosed with a circular ditch. On the right is an orchard, consisting principally of large cherry and peach trees. At the bottom of this orchard, and nearly opposite the eastern end of the house, is a venerable tomb, which contains the remains of the great Washington. This precious monument was the first object of our attention. . . . Situated at the extremity of the grass plot, and on the edge of the bank, it is not seen until you approach near to it. The mound of earth is not much elevated, and is covered over with a growth of cypress trees, a few junipers, and near it the ever-green holly tree, which conceals it from the view until you come almost to it. The side of the steep bank to the river is covered with a thicket of forest trees in its whole extent within view of the house. The tomb opens nearly toward the river, at an upright door, which was locked, and all the stone work is covered with earth, overgrown with tall grass and these trees, which appear to have been planted, except at the sides and over the cap of the door. Between the tomb and the bank, a narrow foot-path, much trodden, and shaded with trees, passes round it. . . . After we had taken a melancholy leave of the tomb, we rambled over the gardens and shrubbery, which discovered much taste and neatness of design in its former owner. . . . I collected a quantity of seeds. . ."

- Birch, William Russell, 1808 (n.p.)[38]

- "This hallowed mansion is founded upon a rocky eminence, a dignified height on the Potomac. During the French war, Admiral Vernon, who commanded the British fleet on this station, frequently made visits to his friend the father of Gen. W. and thence is derived its name. The additions of a piazza to the water front, and of a drawing room, are proofs of the legitimacy of the General's taste. It is now the residence of Judge Washington." [Fig. 3]

- Gerry, Elbridge, Jr., July 1813 (1927: 174)[39]

- "Back of the mansion is a summer house, which commands an elegant view of the Potomac."

- Willis, Nathaniel Parker, 1840 (1840: 2:38-39)[40]

- "The house fronts north-west, the rear looking to the river. In front of the house is a lawn, containing five or six acres of ground, with a serpentine walk around it, fringed with shrubbery, and planted with poplars. On each side of the lawn stands a garden; the one on the right is a flower-garden, and contains two green-houses (one built by General Washington, the other by Judge Washington,) a hot-house, and a pinery. It is laid out in handsome walks, with box-wood borders, remarkable for their beauty. It contains also a quantity of fig-trees, producing excellent fruit. The other is a kitchen-garden containing only fruit and vegetables.

- "About two hundred yards from the house, in a southerly direction, stands a summer-house, on the edge of the river-bank, which is here lofty and sloping, and clothed with wood to the water's edge. The summer-house commands a fine prospect of the river and the Maryland shore; also of the White House, at a distance of five or six miles down the river, where engagement took place with the British vessels which ascended the river during the last war."

- Willis, Nathaniel Parker, 1840, quoting an early visitor's description of Mount Vernon (1840: 39)[40]

- "At the extremity of these extensive alleys and pleasure-grounds, ornamented with fruit-trees and shrubbery, and clothed in perennial verdure, stands two hothouses, and as many green-houses, situated in the sunniest part of the garden, and shielded from the northern winds by a long range of wooden buildings for the accommodation of servants."

Images

Other Resources

Library of Congress Authority File

The Cultural Landscape Foundation

Notes

- ↑ By the time George Washington moved to Mount Vernon, the plantation had already been in the Washington family for several generations. In 1674 John Washington (George Washington’s great-grandfather) and Nicholas Spencer obtained a grant for 5,000 acres of land that included the property now known as Mount Vernon. John Washington’s portion of the land grant passed to his son Lawrence Washington and then to Lawrence’s daughter Mildred Washington Gregory. In 1726 Mildred sold the estate, then named Little Hunting Creek Plantation, to her brother Augustine Washington. Augustine built a house on the property and, in 1735, moved his family (including his three-year-old son George) to the plantation, where they remained for three years before relocating to Ferry Farm in Stafford County, Virginia. Augustine deeded the estate to his son Lawrence Washington (George Washington’s older half-brother) in 1740. In 1743 Lawrence moved to the plantation and renamed it Mount Vernon, in honor of Admiral Edward Vernon (1684–1757), with whom Lawrence had served in the Caribbean in 1741–1742. Lawrence Washington died in 1752, and his will stated that George would inherit Mount Vernon after the death of Lawrence’s wife, Ann Fairfax Washington, and daughter Sarah. On December 17, 1754, Ann offered George, then twenty-two years old, a long-term lease of the plantation. Mount Vernon officially passed into George’s possession upon Ann’s death in 1761. Joseph Manca, George Washington’s Eye: Landscape, Architecture, and Design at Mount Vernon (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 14–15, view on Zotero; Marilynn Larew, "Mount Vernon," National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form (National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1977), 2–3, view on Zotero.

- ↑ For Washington’s use of the term “rusticated” to describe the effect, see Washington’s letter to Lund Washington, August 20, 1775, Washington Papers, Founders Online, National Archives. Washington describes the process of “sanding” in a letter to William Thornton, October 1, 1799, Washington Papers, Founders Online, National Archives. See also Manca 2012, 50, view on Zotero.

- ↑ For more on Washington’s labor practices at Mount Vernon, see Robert F. Dalzell, Jr., and Lee Baldwin Dalzell, George Washington’s Mount Vernon: At Home in Revolutionary America (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), especially pp. 129–187, view on Zotero. Martha Custis brought a fortune of more than £23,000 as well as real estate and hundreds of slaves to the marriage. George Washington also added to the number of slaves working at Mount Vernon. Manca 2012, 2, 14–15, 165, view on Zotero. By June 1797, acting on the advice of his Scottish farm manager, James Anderson, Washington had decided to add a commercial distillery to the operations at Mount Vernon. Letter from George Washington to John Fitzgerald, June 12, 1797, Washington Papers, Founders Online, National Archives.

- ↑ Manca 2012, 14, 52–53, 110–111, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Adam T. Erby, “Designing the Beautiful: General Washington’s Landscape Improvements, 1784–1787,” in The General in the Garden: George Washington’s Landscape at Mount Vernon, ed. by Susan P. Schoelwer (Mount Vernon, Va.: Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, 2015), 28, view on Zotero.

- ↑ In a diary entry for February 18, 1795, Washington wrote that “four Lime or Linden Trees, sent to me by Govr. Clinton of New York. . . .were planted in the Serpentine Roads to the door.” Washington Papers, Founders Online, National Archives. See also George Washington, January 6, 1785, letter to George Augustine Washington, Washington Papers, Founders Online, National Archives.

- ↑ Dalzell and Dalzell 1998, 116–119, view on Zotero; Manca 2012, 85; view on Zotero.

- ↑ Washington ordered Langley’s book from a London-based merchant house on May 1, 1759, and kept a copy of it in his library for the remainder of his life. See George Washington’s Invoice to Robert Cary & Company, May 1, 1759, Washington Papers, Founders Online , National Archives. At the time of his death, Washington owned the abridged version of Philip Miller’s Gardener’s Dictionary (1763), Washington Papers, Founders Online, National Archives. Washington’s library also contained Thomas Mawe and John Abercrombie’s The Universal Gardener and Botanist (1778). See Therese O’Malley, “Appropriation and Adaptation: Early Gardening Literature in America,” Huntington Library Quarterly 55, no. 3 (Summer 1992): 421–424, view on Zotero; Dennis J. Pogue, “Giant in the Earth: George Washington, Landscape Designer,” in Landscape Archaeology: Reading and Interpreting the American Historical Landscape, ed. by Rebecca Yamin and Karen Bescherer Metheny (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1996), 57–59, view on Zotero.

- ↑ For additional discussion of Vaughan’s drawings of Mount Vernon, see Erby 2015, “Designing the Beautiful,” 32, 34, view on Zotero; Manca 2012, 85, 88–89, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Manca 2012, 104, 106–109, view on Zotero; Adam T. Erby, “Gardens and Groves: A Landscape Guide,” in Schoelwer 2015, 114, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Pogue 1996, 59, view on Zotero. According to Erby, Washington’s friend Henrich Wilmans of Bremen, Germany, dined at Mount Vernon in November 1788 and offered to help Washington find a suitable gardener from Germany. Wilmans hired Ehlers on Washington’s behalf in 1789. Ehlers arrived to New York City, where he was met by Washington’s secretary, Tobias Lear, and then sent to Mount Vernon via stage coach. Ehlers oversaw a team of two or three enslaved gardeners, and he reported to the farm manager. Washington opted not to renew Ehler’s contract after it expired, apparently exasperated by Ehler’s reported propensity to abuse alcohol, and he sought the help of his friend James Anderson in finding a new gardener from Scotland because he believed Scotsmen to be especially industrious and because the Scottish climate was similar to that of Virginia. Erby 2015, “Designing the Beautiful,” 31–32, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Erby 2015, “Gardens and Groves,” 18, 118, 120, view on Zotero; Manca 2012, 27–33, 98, view on Zotero. According to Manca, “by the 1790s the presence of slaves on the estate was a point of shame in Washington’s national and international reputation, and he took steps to shield visitors from seeing them” (95). For a detailed analysis of the slave quarters at Mount Vernon, see Dennis J. Pogue, “The Domestic Architecture of Slavery at George Washington’s Mount Vernon,” Winterthur Portfolio 37, no. 1 (Spring 2002): 3–22, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Pogue 1996, 60–65, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Many of the plants sent from Bartram’s died upon arrival and were replaced with an additional shipment in November. For lists of the plants that Washington obtained from Bartram and Hamilton, see Erby 2015, “Gardens and Groves,” 143–155, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Manca 2012, 168, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Ibid., 155–161, view on Zotero; Erby 2015, “Gardens and Groves,” 104, 116–117, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Manca 2012, 33, 82, 142, view on Zotero.

- ↑ For more on the ownership of Mount Vernon after George Washington’s death in 1799, see Esther C. White, “‘Laid Out in Squares, and Boxed with Great Precision’: Uncovering George Washington’s Upper Garden,” in Schoelwer 2015, 86, 89–90, view on Zotero. For a detailed history of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association’s restorations of the grounds at Mount Vernon, see J. Dean Norton, “George Washington’s Gardens: Under the Watchful Eye of the Mount Vernon Ladies,” in Schoelwer 2015, 39–69, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Founders Online, National Archives, Washington Papers, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-06-02-0078.

- ↑ Gerald W. Johnson, Mount Vernon: The Story of a Shrine (New York: Random House, 1953), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Founders Online, National Archives, Washington Papers, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/04-01-02-0033.

- ↑ Founders Online, National Archives, Washington Papers, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/04-02-02-0032.

- ↑ John C. Fitzpatrick, ed., The Diaries of George Washington, 1748–1799, 4 vols (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company for the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, 1925), ii, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Donald Jackson and Dorothy Twohig, eds., The Diaries of George Washington, 6 vols. (Charlottesville, Va.: University Press of Virginia, 1978), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Founders Online, National Archives, Washington Papers, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/04-02-02-0267.

- ↑ Founders Online, National Archives, Washington Papers, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/04-03-02-0385.

- ↑ John D. Norton and Susanne A. Schrage-Norton, The Upper Garden at Mount Vernon Estate—Its Past, Present, and Future: A Reflection on 18th Century Gardening. Phase II: The Complete Report (Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association Library, 1985), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Founders Online, National Archives, Washington Papers, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/04-05-02-0397.

- ↑ J.-P. (Jacques-Pierre) Brissot de Warville, New Travels in the United States Performed in 1788 (Bowling Green, Ohio: Historical Publications Co., 1919), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Elizabeth Cometti, ed., The American Journals of Lt. John Enys (Syracuse, N.Y.: Adirondack Museum and Syracuse University Press, 1976), view on Zotero.

- ↑ David Humphreys, unpublished manuscript of an authorized biography of George Washington, quoted in Manca 2012, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Isaac Weld, Jr., Travels through the States of North America and the Provinces of Upper and Lower Canada, during the Years 1795, 1796, and 1797, 2nd edition, 2 vols (London: John Stockdale, 1799), i, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Founders Online, National Archives, Washington Papers, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-00588.

- ↑ Benjamin Henry Latrobe, The Virginia Journals of Benjamin Henry Latrobe, 1795–1798, edited by Edward C. Carter II, 2 vols. (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1977), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Founders Online, National Archives, Washington Papers, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/06-02-02-0204.

- ↑ Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz, Under Their Vine and Fig Tree: Travels through America in 1797–99, 1805, with Some Further Account of Life in New Jersey, ed. & trans. by Metchie J. E. Budka, Collections of The New Jersey Historical Society at Newark (Elizabeth, NJ: The Grassmann Publishing Company, 1965), xiv, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Manasseh Cutler, Life, Journals and Correspondence of Rev. Manasseh Cutler, L.L.D., ed. William Parker Cutler and Julia Perkin Cutler, 2 vols. (Cincinnati: Robert Clarke & Co., 1888), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Russell Birch, The Country Seats of the United States of North America: With Some Scenes Connected with Them (Springland, Pa.: W. Birch, 1808), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Elbridge Gerry, Jr., The Diary of Elbridge Gerry, Jr (New York: Brentano’s, 1927), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Nathaniel Parker Willis, American Scenery; or, Land, Lake and River Illustrations of Transatlantic Nature (London: G. Virtue, 1840), vol. 2, view on Zotero.