Difference between revisions of "Picturesque"

V-Federici (talk | contribs) m (→Associated) |

|||

| (196 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

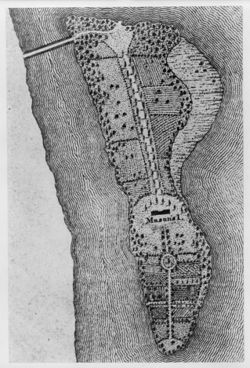

| − | The picturesque is an aesthetic category | + | [[File:0379.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 1, Anonymous, “View of a Picturesque farm (''ferme ornée''),” in [[Andrew Jackson Downing|A. J. Downing]], ''A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening'', 4th ed. (1849), 120, fig. 27.]] |

| − | derived from the idea of designing landscapes | + | The picturesque is an aesthetic category derived from the idea of designing landscapes to look like pictures. The picturesque was at its height in Britain around the turn of the 19th century, though its development began much earlier and it is still in use today. In American landscape discourse, the term “picturesque” had two important uses. The first referred to a garden style with specific compositional components detailed by theorists such as Thomas Whately and [[Andrew Jackson Downing|A. J. Downing]]. The picturesque also came to be understood as a visual effect achieved by the incorporation of natural and designed landscape elements into a [[prospect]] or [[view]]. <span id="Loudon_cite"></span>This second sense is clear in [[J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon|J. C. Loudon’s]] 1826 claim that a [[view]] was picturesque if “it would form a tolerable picture” when painted ([[#Loudon|view text]]). This use of the term was used frequently in travelers’ descriptions of towns, settlements, or gardens. <span id="Downing_cite"></span>[[A. J. Downing|Downing]] later echoed [[J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon|Loudon]] when he wrote that “the picturesque is nature or art obeying the same laws rudely” (1849) ([[#Downing|view text]]). It is evident that during their historical development, both senses of this term, as either a style or a visual effect, were frequently used simultaneously. <span id="Bartram_cite"></span>In addition, in many cases the term “picturesque” served as an effective expression meaning simply an attractive or pleasing scene, as in the case of [[William Bartram|William Bartram’s]] romantic and evocative descriptions of his travels in the south (1792) ([[#Bartram|view text]]). The goal of the picturesque was to re-create in the garden the experience of the natural landscape. The chief characteristics of the picturesque were surprise and variety, in contrast to the effects of terror and awe associated with the sublime. These characteristics were defined by the theorists Whately and William Gilpin, whose treatises were well known in America. <span id="Cutler_cite"></span>At [[Mount Vernon]], [[Manasseh Cutler]] reported in 1802 that the picturesque effect was enhanced by “coming out of a thick [[wood]], and the sudden and unexpected manner in which it was seen,” underscoring the importance of surprise to the picturesque effect ([[#Cutler|view text]]). Similarly, sinuous routes through the garden afforded a “continual change of scenery.” In reference to his picturesque [[plantation]]s, [[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing]] claimed that the effect depended upon “''intricacy'' and ''irregularity''.”<ref>A. J. Downing, ''A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening'', 4th ed. (New York: G. P. Putnam, 1849), 103, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/5M4S2D64 view on Zotero].</ref> |

| − | to look like pictures. The picturesque | ||

| − | was at its height in Britain around the turn | ||

| − | of the | ||

| − | began much earlier and it is still in | ||

| − | use today. In American landscape discourse, | ||

| − | the term “picturesque” had two important | ||

| − | uses. The first referred to a garden style | ||

| − | with specific compositional components | ||

| − | detailed by theorists such as Thomas | ||

| − | Whately and A. J. Downing. The picturesque | ||

| − | also came to be understood as a visual effect | ||

| − | achieved by the incorporation of natural and | ||

| − | designed landscape elements into a | ||

| − | prospect or view. This second sense is clear | ||

| − | in J. C. Loudon’s 1826 claim that a view was | ||

| − | picturesque if “it would form a tolerable picture” | ||

| − | when painted. This use of the term | ||

| − | was used frequently in travelers’ descriptions | ||

| − | of towns, settlements, or gardens. | ||

| − | Downing later echoed Loudon when he | ||

| − | wrote that “the picturesque is nature or art | ||

| − | obeying the same laws rudely” (1849). It is | ||

| − | evident that during their historical development, | ||

| − | both senses of this term, as either a | ||

| − | style or a visual effect, were frequently used | ||

| − | simultaneously. In addition, in many cases | ||

| − | the term “picturesque” served as an effective | ||

| − | expression meaning simply an attractive | ||

| − | or pleasing scene, as in the case of William | ||

| − | Bartram’s romantic and evocative descriptions | ||

| − | of his travels in the south (1792). | ||

| − | The goal of the picturesque was to re-create | ||

| − | in the garden the experience of the natural | ||

| − | landscape. The chief characteristics of the | ||

| − | picturesque were surprise and variety, in | ||

| − | contrast to the effects of terror and awe | ||

| − | associated with the sublime. These characteristics | ||

| − | were defined by the theorists | ||

| − | Whately and William Gilpin, whose treatises | ||

| − | were well known in America. At Mount Vernon, | ||

| − | |||

| − | that the picturesque effect was enhanced by | ||

| − | “coming out of a thick wood, and the sudden | ||

| − | and unexpected manner in which it was | ||

| − | seen,” underscoring the importance of surprise | ||

| − | to the picturesque effect. Similarly, | ||

| − | sinuous routes through the garden afforded | ||

| − | a “continual change of scenery.” In reference | ||

| − | to his picturesque | ||

| − | claimed that the effect depended upon | ||

| − | |||

| − | In A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts | + | [[File:1807.jpg|thumb|Fig. 2, George Inness, ''Sunnyside'', c. 1850–60.]] |

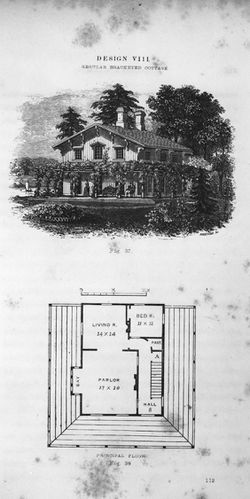

| − | and Sciences (1816), G. Gregory insisted that | + | <span id="Gregory_cite"></span>In ''A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences'' (1816), [[G. (George) Gregory|George Gregory]] insisted that the picturesque garden was possible only in properties that exceeded twenty acres; smaller lots were considered ridiculous for such a function. He thus defines the picturesque garden as part of the larger designed landscape, a portion apart from the house, and extensive and often synonymous with “[[park]]” ([[#Gregory|view text]]). Any part of a designed landscape, however, could be produced in the picturesque mode, even the [[ferme ornée|ornamental farm]] as illustrated by [[A. J. Downing|Downing]] [Fig. 1]. |

| − | the picturesque garden was possible only in | ||

| − | properties that exceeded twenty acres; | ||

| − | smaller lots were considered ridiculous for | ||

| − | such a function. He thus defines the picturesque | ||

| − | garden as part of the larger designed | ||

| − | landscape, a portion apart from the house, | ||

| − | and extensive and often synonymous with | ||

| − | |||

| − | however, could be produced in the picturesque | ||

| − | mode, even the ornamental farm as | ||

| − | illustrated by Downing [Fig. 1]. | ||

| − | The concept of the picturesque was critical | + | The concept of the picturesque was critical to [[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing’s]] approach and a continuous theme in his ''Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening'' (1849). [[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing]] defined the picturesque as a style distinct from the beautiful mode of design, but considered both varieties of the [[modern style|modern]] or [[natural style]] of [[landscape gardening]]: the “Beautiful” expressed simple and flowing forms, whereas the “Picturesque” had striking, irregular and “pointed” forms. He illustrated the latter term with cottage houses set on relatively modest lots [<span id="Fig_17_cite"></span>[[#Fig_17|See Fig. 17]]]. The picturesque style, according to [[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing]], was achieved not by size (contrary to [[G. (George) Gregory|Gregory’s]] definition), but by shapes and outlines of trees, architecture, and grounds. For [[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing]], the term represented primarily a rejection of all regular and geometric forms in landscape design. |

| − | to Downing’s approach and a continuous | ||

| − | theme in his Treatise on the Theory and Practice | ||

| − | of Landscape Gardening (1849). Downing | ||

| − | defined the picturesque as a style distinct | ||

| − | from the beautiful mode of design, but considered | ||

| − | both varieties of the modern or natural | ||

| − | style of landscape gardening: the | ||

| − | “Beautiful” expressed simple and flowing | ||

| − | forms, whereas the “Picturesque” had striking, | ||

| − | irregular and “pointed” forms. He illustrated | ||

| − | the latter term with cottage houses | ||

| − | set on relatively modest lots [Fig. | ||

| − | style, according to Downing, was | ||

| − | + | <div id="Fig_3"></div>[[File:0580.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 3, Lewis Miller, “[[Mount Vernon]]” [detail], in ''Orbis Pictus'' (c. 1849), 108. [[#Fig_3_cite|Back to texts]]]] | |

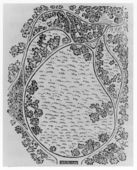

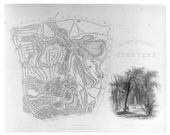

| − | + | <span id="Register_cite"></span>Instructions for laying out the picturesque garden were found in garden literature such as the ''Horticultural Register'', which stated in 1837 that the picturesque was a “facsimile imitation of natural scenery” ([[#Register|view text]]). In his treatise, [[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing]] advocated that trees should stand in irregular groups not in straight rows, and paths and [[border]]s should be winding or serpentine, adapting to the natural inequalities of the surface. Several writers recommended that any sign of artifice should be disguised. | |

| − | trees, | ||

| − | the | ||

| − | of | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[File:0089.jpg|thumb|Fig. 4, [[Benjamin Henry Latrobe]], ''View of [[Mount Vernon]] looking towards the South West'', 1796.]] | |

| − | + | <span id="Downing_1850_cite"></span>American scenery, according to [[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing]] and his contemporaries, was a place where, he wrote in 1850, “the wildness or grandeur of nature triumphs strongly over cultivated landscape,” and ultimately harmonizes with the boldly varied picturesque style ([[#Downing_1850|view text]]). The ingredients of [[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing’s]] picturesque included an architecture of projecting profiles and bold outlines, specific vegetation, such as larch trees, and planting schemes of irregular groups. The desired effect could be achieved, according to [[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing]], at little cost, even on small properties such as farms. He illustrated the picturesque garden in his ''Treatise'' with winding lanes, irregular groups of trees, and untrimmed [[hedge]]s giving a less formal, and a more free and natural air. | |

| − | such as | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

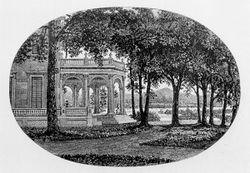

| − | + | [[File:0417.jpg|thumb|Fig. 5, Anonymous, “[[Rustic_style|Rustic]] [[prospect]]-[[arbor]],” in [[Andrew Jackson Downing|A. J. Downing]], ''A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening'', 4th ed. (1849), 460, fig. 87.]] | |

| − | + | Numerous representations and descriptions of designed landscapes emphasized the picturesque aesthetics of the site, exemplified by both image and text of Washington Irving’s [[Sunnyside]] [Fig. 2]. Gardens laid out with picturesque features have been documented from the 1740s in the British colonies, in such places as Henry Middleton’s [[seat]], Middleton Place, and William Middleton’s [[plantation]], Crowfield, both near Charleston, South Carolina. In 1802, [[Manasseh Cutler|Cutler]] determined that [[Mount Vernon]] had “quite a picturesque appearance” because of the successful integration of the building with the surrounding trees. Lewis Miller’s 1849 illustrated account of his visit to [[Mount Vernon]] [Fig. 3] repeated [[Manasseh Cutler|Cutler’s]] description of Washington’s home as picturesque. <span id="Miller_cite"></span>In the sketch Miller did not position the [[plantation]] symmetrically (a [[view]] that might have emphasized the bilateral symmetry of the design), but presented the house from an oblique angle that depicted the house off-center, focusing more on the “little [[copse]]s [and] [[clump]]s” that add “a romantick and picturesque appearance to the whole Scenery” ([[#Miller|view text]]). [[Mount Vernon]] was a particularly interesting example because specific aspects of its design were often criticized for not being in the more modern, picturesque style. It seems that although individual elements were not deemed to be picturesque, the entire effect of house, gardens, and extended landscape could still be. This tension is also expressed in [[Benjamin Henry Latrobe|Benjamin Henry Latrobe's]] [[view]]s of [[Mount Vernon]] [Fig. 4]; [[Benjamin Henry Latrobe|Latrobe]] used picturesque conventions to depict the house, even though his written critique of the gardens expressed displeasure with its symmetrical [[parterre]]s.<ref>''The Virginia Journals of Benjamin Henry Latrobe, 1795–1798'', ed. Edward C. Carter II (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1977), 1:165, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/SZEEBG9K view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | of | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | the picturesque | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In 1829, at a meeting of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, the picturesque garden was presented as one garden type in a list that included the [[kitchen garden|kitchen]], [[flower garden|flower]], and [[botanic garden|botanical gardens]]. Its component parts included the imitation ruin, [[rustic style|rustic]] ornament, and exotic styles as indicated by [[André Parmentier|André Parmentier’s]] advertisement for his services. The [[rustic style|rustic]] [[prospect tower]] at [[Parmentier’s Horticultural and Botanical Garden]] in Brooklyn, New York, was praised by [[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing]] as one of the “most fitting decorations of the Picturesque landscape garden” [Fig. 5]. In the first quarter of the 19th century, [[Parmentier’s Horticultural and Botanical Garden]] was frequently described in the farm and garden press as an important exemplar of the picturesque. In his own article entitled “Landscape and Picturesque Gardens” of 1828, [[André Parmentier|Parmentier]] described this [[modern style]], the picturesque, as reinstating “Nature in the possession of those rights from which she has too long been banished by an undue regard to symmetry.” | |

| − | of | ||

| − | picturesque | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | the | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [Fig. 5] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [and] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | <span id="Willis_cite"></span>Nathaniel Parker Willis in ''American Scenery'' (1840), made a distinction between the picturesque in American landscape and that elsewhere. In Europe, ruins—symbols of history—were central to the experience of the picturesque. In the United States, however, the “eternal succession of lovely natural objects,” was for Willis, expressive of the future ([[#Willis|view text]]). | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | —''Therese O’Malley'' | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | <hr> | |

==Texts== | ==Texts== | ||

| + | ===Usage=== | ||

| + | *<div id="Bartram"></div>[[William Bartram|Bartram, William]], 1792, describing islands off the coast of Georgia and Florida (1996: 93)<ref>William Bartram, ''Travels, and Other Writings'', ed. Thomas Slaughter (New York: Library of America, 1996), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/MJ8STDET view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“These floating islands present a very entertaining [[prospect]]; for although we behold an assemblage of the primary productions of nature only, yet the imagination seems to remain in suspense and doubt; as in order to enliven the delusion, and form a most '''picturesque''' appearance, we see not only flowery plants, [[clump]]s of [[shrub]]s, old-weather beaten trees, hoary and barbed, with the long moss waving from their snags, but we also see them completely inhabited, and alive, with crocodiles, serpents, frogs, otters, crows, herons, curlews, jackdaws, &c. There seems, in short, nothing wanted but the appearance of a wigwam and a canoe to complete the scene.” [[#Bartram_cite|back up to History]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | *Brown, Charles Brockden, 1798, describing the fictional estate of Wieland, near Philadelphia, PA (1798: 54–55)<ref>Charles Brockden Brown, ''Wieland, or The Transformation, An American Tale'' (New York: T. & J. Swords, 1798), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/5CB78G5T view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“No scene can be imagined less enticing to a lover of the '''picturesque''' than this. . . | ||

| + | :“The scenes which environed our dwellings at Mettingen constituted the reverse of this. [[Schuylkill River|Schuylkill]] was here a pure and translucid current, broken into wild and ceaseless music by rocky points, murmuring on a sandy margin, and reflecting on its surface banks of all varieties of height and degrees of declivity. These banks were chequered by patches of dark verdure and shapeless masses of white marble, and crowned by [[copse]]s of cedar, or by the regular magnificence of [[orchard]]s, which, at this season, were in blossom, and were prodigal of odours. The ground which receded from the river was scooped into valleys and dales. Its beauties were enhanced by the horticultural skill of my brother, who bedecked this exquisite assemblage of [[slope]]s and risings with every species of vegetable ornament, from the giant arms of the oak to the clustering tendrils of the honeysuckle.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | *<div id="Cutler"></div>[[Manasseh Cutler|Cutler, Manasseh]], January 2, 1802, describing [[Mount Vernon]], [[plantation]] of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (1987: 2:56)<ref>William Parker Cutler, ''Life, Journals, and Correspondence of Rev. Manasseh Cutler, LL.D.'', 2 vols. (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1987), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/3PBNT7H9 view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“It appears on an [[eminence]], not like a hill, but a level ground, with a pretty deep valley between, covered with [[wood]]s and bushes of different kinds, which conceal the winding passage from the [[gate]] to the house. . . In this situation the house, with two ranges of small buildings extending in a curved form, from near the corners of the house, till interrupted by the trees, has quite a '''picturesque''' appearance, and the effect is much heightened by coming out of a thick [[wood]], and the sudden and unexpected manner in which it is seen.” [[#Cutler_cite|back up to History]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[File:0565.jpg|thumb|Fig. 6, Robert King, Detail of Analostan Island from Map of the City of Washington, 1818.]] | |

| − | + | *Warden, David Bailie, 1816, describing Analostan Island, seat of Gen. John Mason, Washington, DC (quoted in Phillips 1917: 49)<ref>Philip Lee Phillips, ''The Beginnings of Washington: As Described in Books, Maps, and Views'' (Washington, DC: The author, 1917), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/QXZXNN8N view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“The [[view]] from this spot is delightful. It embraces the '''picturesque''' banks of the Potomac, a portion of the city, and an expanse of water, of which the [[bridge]] terminates the [[view]].” [Fig. 6] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Anonymous, September 10, 1817, describing in the ''Virginia Herald'' a property for sale in Westmoreland County, VA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation) | |

| − | + | :“Rappahannock land. For sale. . . The situation is high, healthy, and '''picturesque'''; from the south door, you overlook the rich scenery of the Rappahannock for a great extent; and from the north, you have a fine [[view]] of the Potomac, whitened by the rapidly-increasing commerce of the District of Columbia.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[File:1052.jpg|thumb|Fig. 7, Daniel Wadsworth, “Monte Video,” in Benjamin Silliman, ''Remarks Made on a Short Tour between Hartford and Quebec'' (1824), frontispiece.]] | |

| + | *Silliman, Benjamin, 1824, describing Monte Video, property of Daniel Wadsworth, Avon, CT (1824: 15)<ref>Benjamin Silliman, ''Remarks Made on a Short Tour between Hartford and Quebec, in the Autumn of 1819'' (New Haven, CT: S. Converse, 1824), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/B5VWTWM5 view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“The little spot of cultivation surrounding the house, and the [[lake]] at your feet, with its '''picturesque''' appendages of winding paths, and Gothic buildings, shut in by rocks and forests, compose the fore-ground of this grand Panorama.” [Fig. 7] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Anonymous, April 28, 1826, “On Landscapes and Picturesque Gardens” (''New England Farmer'' 4: 316)<ref>Anonymous, “On Landscape and Picturesque Gardens,” ''New England Farmer'' 4, no. 40 (April 28, 1826): 316, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/I3K5QGBZ view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“[[André Parmentier|Mr. [Andrew] P[armentier]]]. by the advice of several of his friends, will furnish plans of landscape and '''picturesque''' gardens; he will communicate to gentlemen who wish to see him, a collection of his drawings of Cottages, Rustic [[Bridge]]s, Dutch, [[Chinese manner|Chinese]], Turkish, French [[Pavilion]]s, [[Temple]]s, [[Hermitage]]s, Rotundas, &c. For further particulars, inquiries personally, or by letter, addressed to him, post paid, will be attended to.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Hall, Capt. Basil, 1828, describing a “bungalow” in Alabama (quoted in Lockwood 1934: 2:389)<ref>Alice B. Lockwood, ed., ''Gardens of Colony and State: Gardens and Gardeners of the American Colonies and of the Republic before 1840'', 2 vols. (New York: Charles Scribner’s for the Garden Club of America, 1931–34), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/JNB7BI9T view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“We soon left our comfortless abode [the inn] for as neat and trig a little villa as ever was seen in or out of the Tropics. This mansion, which in India would be called a Bungalow, was surrounded by white railings, within which lay an ornamental garden, intersected by gravel [[walk]]s, almost too thickly shaded by orange [[hedge]]s, all in flower. From the light airy, broad [[veranda|verandah]], we might look upon the Bay of Mobile. . . Many similar houses nearly as '''picturesque''' as our own delightful habitation, speckled the landscape in the south and east, in rich keeping with the luxuriant foliage of that evergreen latitude.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | the | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

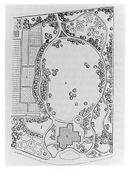

| − | + | [[File:0064.jpg|thumb|Fig. 8, Anonymous, ''Map of [[Parmentier’s_Horticultural_and_Botanical_Garden|Mr. Andrew Parmentier’s Horticultural & Botanic Garden]], at Brooklyn, Long Island, Two Miles From the City of New York'', c. 1828.]] | |

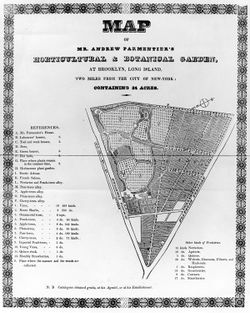

| − | + | *Anonymous, October 3, 1828, “Parmentier’s Horticultural Garden,” describing [[André Parmentier|André Parmentier’s]] horticultural and [[botanic garden|botanical garden]], Brooklyn, NY (''New England Farmer'' 7: 85)<ref>Anonymous, “Parmentier’s Horticultural Garden,” ''New England Farmer, and Horticultural Journal'' 7, no. 11 (October 3, 1828): 84–85, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/ZC2KF67E view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“The [[greenhouse|green-house]] department, although not so extensive as some in our vicinity, contains many beautiful plants exhibited with the same tasteful arrangement which characterizes the whole of [[André Parmentier|Mr. Parmentier’s]] establishment; even the method in disposing the [[pot]]s according to some principle of grouping or contrasting the color and size of the flowers, entertains the eve, and shows the variety of ways in which a skillful gardener may distribute his materials to produce '''picturesque''' effect.” [Fig. 8] | |

| − | |||

| − | the | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Committee of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1830, describing [[Lemon Hill]], estate of [[Henry Pratt]], Philadelphia (quoted in Boyd 1929: 432)<ref>James Boyd, ''A History of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1827–1927'' (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1929), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/UN9TRH8T view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“In [[landscape gardening]], water and [[wood]] are indispensable for '''picturesque''' effect; and here they are found distributed in just proportions with hill and [[lawn]] and buildings of architectural beauty, the whole scene is cheerfully animated by the brisk commerce of the river, and constant movement in the busy neighborhood of Fairmount.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

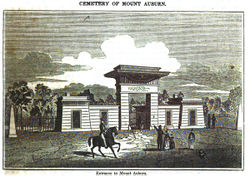

| − | + | *Dearborn, H. A. S., 1832, describing [[Mount Auburn Cemetery]], Cambridge, MA (quoted in Harris 1832: 64–65)<ref>Thaddeus William Harris, ''A Discourse Delivered before the Massachusetts Horticultural Society on the Celebration of Its Fourth Anniversary, October 3, 1832'' (Cambridge, MA: E. W. Metcalf, 1832), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/3A3UDHF3/ view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“. . . it is proposed, that a tract of land called 'Sweet Auburn,' situated in Cambridge, should be purchased. As a large portion of the ground is now covered with trees, [[shrub]]s, and wild flowering plants, [[avenue]]s and [[walk]]s may be made through them, in such a manner as to render the whole establishment interesting and beautiful, at a small expense, and within a few years; and ultimately offer an example of landscape or '''picturesque''' gardening, in conformity to the [[modern style]] of laying out grounds, which will be highly creditable to the Society.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | the | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[File:1025.jpg|thumb|Fig. 9, Anonymous, “Entrance to [[Mount Auburn Cemetery|Mount Auburn]]]] | |

| − | + | *Hawthorne, Elizabeth Manning and Hawthorne, Nathaniel describing [[Mount Auburn Cemetery]], in ''American Magazine of Useful and Entertaining Knowledge'' 1, no. 1 (September 1834: 9)<ref>Cemetery of Mount Auburn, in ''American Magazine of Useful and Entertaining Knowledge'' 1, no. 1 (September 1834): 9 [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/8EK3TUJQ view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :. . . On the north, at a very small distance, Fresh [[Pond]] appears, a handsome sheet of water, finely diversified by its woody and irregular shores. Country [[seat]]s and cottages in various direction, and especially those on the elevated land at Watertown, add much to the '''picturesque''' effect of the scene. It is proposed, at some future period, to erect on the summit of [[Mount Auburn Cemetery|Mount Auburn]], a Tower, after some classic model, of sufficient height to rise above the tops of the surrounding trees. This will serve the double purpose of a land-mark, to identify the spot from a distance, and of an [[Belvedere/Prospect tower/Observatory|observatory]] commanding an uninterrupted [[view]] of the country around it. | |

| − | + | :. . . The grounds of the [[Cemetery/Burying ground/Burial ground|Cemetery]] have been laid out with intersecting [[avenue]]s, so as to render every part of the wood accessible. These [[avenue]]s are curved and variously winding in their course, so as to be adapted to the natural inequalities of the surface. By this arrangement, the greatest economy of the hand is produced, combining at the same time the [[picturesque]] effect of [[landscape gardening]]. [Fig. 9] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | the | ||

| − | |||

| − | effect. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Ritchie, Anna Cora Ogden Mowatt, 1839, describing [[Point_Breeze|Bonaparte’s Park]] at estate of Joseph Bonaparte (Count de Survilliers), Bordentown, NJ (quoted in Weber 1854: 186)<ref>Constance Weber, “A Sketch of Joseph Bonaparte,” in ''Godey’s Lady’s Book'' (Philadelphia: L. A. Godey, 1854), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/NEDC6TSD view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“The only portion of the building left is the [[Belvedere|observatory]], which is surrounded by a stone enclosure and looked like a miniature ruin left purposely in this dilapidated state to add to the '''picturesqueness''' of the scene. A narrow stream winds itself gracefully through one part of the grounds, over which several [[rustic style|rustic]] [[bridge]]s are erected. Equally [[rustic style|rustic]] [[seat]]s are scattered beneath the shade of the tall trees on its banks, and upon its clear surface a flock of snow-white swans were floating about.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | the | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

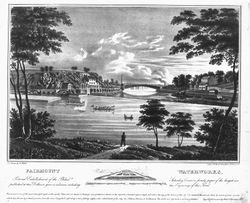

| − | + | *<div id="Willis"></div>Willis, Nathaniel Parker, 1840, describing the Fairmount Waterworks, Philadelphia (1840; repr., 1971: 3–4, 313)<ref>Nathaniel Parker Willis, ''American Scenery, or Land, Lake and River Illustrations of Transatlantic Nature'', 2 vols. (1840; repr., Barre, MA: Imprint Society, 1971), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/T5CMW67U view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“The interest, with regard to both the natural and civilized features of America, has very much increased within a few years; and travelers [''sic''], who have exhausted the unchanging countries of Europe, now turn their steps in great numbers to the novel scenery, and ever-shifting aspects of this. | |

| − | + | :“The '''picturesque''' [[view]]s of the United States suggest a train of thought directly opposite to that of similar objects of interest in other lands. There, the soul and centre of attraction in every picture is some ruin of the ''past''. The wandering artist avoids every thing that is modern, and selects his point of [[view]] so as to bring prominently into his sketch, the castle, or the cathedral, which history or antiquity has hallowed. The traveller visits each spot in the same spirit—ridding himself, as far as possible, of common and present associations, to feed his mind on the historical and legendary. The objects and habits of reflection in both traveller and artist undergo in America a direct revolution. He who journeys here, if he would not have the eternal succession of lovely natural objects— | |

| − | now | + | [[File:0540.jpg|thumb|Fig. 10, John Caspar Wild, ''Fairmount Waterworks'', 1838.]] |

| − | + | :“'Lie like a load on the weary eye,' must feed his imagination on the ''future''. The American does so. His mind, as he tracks the broad rivers of his own country, is perpetually reaching forward. Instead of looking through a valley, which has presented hundreds of years—in which live lords and tenants, whose hearths have been surrounded by the same names through ages of tranquil descent, and whose fields have never changed landmark or mode of culture since the memory of man, he sees a valley laden down like a harvest wagon [''sic''] with a virgin vegetation, untrodden and luxuriant; and his first thought is of the villages that will soon sparkle on the hillsides, the axes that will ring from the woodlands, and the mills, [[bridge]]s, [[canal]]s, and railroads, that will span and [[border]] the stream that now runs through sedge and wild-flowers. The towns he passes through on his route are not recognizable by prints done by artists long ago dead, with houses of low-browed architecture, and immemorial trees; but a town which has perhaps doubled its inhabitants and dwellings since he last saw it, and will again double them before he returns. Instead of inquiring into its antiquity, he sits over the fire with his paper and pencil, and calculates what the population will be in ten years, how far they will spread, what the value of the neighbouring land will become, and whether the stock of some [[canal]] or railroad that seems more visionary than Symmes’s expedition to the centre of the earth, will, in consequence, be a good investment. He looks upon all external objects as exponents of the future. In Europe they are only exponents of the past. . . | |

| + | :“Steps and [[terrace]]s conduct to the reservoirs, and thence the [[view]] over the ornamented grounds of the country [[seat]]s opposite, and of a very '''picturesque''' and uneven country beyond, is exceedingly attractive. Below, the court of the principal building is laid out with gravel [[walk]]s, and ornamented with [[fountain]]s and flowering trees; and within the edifice there is a public drawing-room, of neat design and furniture; while in another wing are elegant refreshment-rooms—and, in short, all the appliances and means of a place of public amusement.” [Fig. 10] [[#Willis_cite|back up to History]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[File:0032.jpg|thumb|Fig. 11, [[Robert Mills]], ''Picturesque View of the Building, and Grounds in front'', 1841.]] | |

| + | *[[Robert Mills|Mills, Robert]], February 23?, 1841, describing his design for the [[National Mall]], Washington, DC (Scott 1990: n.p.)<ref>Pamela Scott, ed., ''The Papers of Robert Mills'' (Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Resources, 1990), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/9CEBJWW8 view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“By means of Groups and [[vista]]s of trees, '''picturesque''' [[view]]s may be obtained of the various buildings and such other objects as may be of a monumental character and thus there would be an attraction produced which would draw many of our citizens and strangers to partake of the pleasure of promenading here.” [Fig. 11] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), August 1841, “Notes made during a Visit to New York, &c.,” describing Presque Isle, residence of William Demming, Fishkill, NY (''Magazine of Horticulture'' 7: 374)<ref>Charles Mason Hovey, “Notes Made during a Visit to New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington, and Intermediate Places, from August 8th to the 23rd, 1841,” ''Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs'' 7, no. 10 (October 1841): 361–74, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/XQ37WZ9M view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“Beyond the grouping of trees on the bank of the river, and the stately forms of some of the single specimens on the [[lawn]], we found but little to notice. Of the former we can speak in gratifying terms; for we are delighted to be able to give our evidence of the existence of so much of that landscape beauty among us, which is almost exclusively the peculiar feature of the gardening of Britain. Nature, it is true, has done much for the place, but art has also accomplished a great deal. . . | |

| − | + | :“Through the belt on the [[border]] of the river, by cutting away the branches, [[view]]s of the most interesting portions of the opposite side of the river have been opened. Were the [[lawn]] only kept closer, and more frequently mown, the [[walk]]s filled with gravel and well rolled, we could have imagined ourselves in some of the fine old '''picturesque''' places of England.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | the | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Adams, Nehemiah, 1842, describing [[Boston Common]], Boston, MA (1842: 11–12)<ref>Nehemiah Adams, ''Boston Common'' (Boston: William D. Ticknor and H. B. Williams, 1842), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/VXTWGJ58 view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“It is seldom that a piece of ground is seen which, with no greater extent, is so diversified in surface and combines so much in itself that is '''picturesque''', as the [[Boston Common|Common]]. There is hill and plain, [[meadow]] and upland, in it. It has sufficient irregularity to make a pleasing variety of surface without being rough; its elevations are well sloped towards the plain part of the enclosure; indeed it would be difficult for art to arrange the surface of the [[Boston Common|Common]] more agreeably for pleasing effect or use.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | the | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *W., February 1842, describing Lowell Cemetery, Lowell, MA (''Magazine of Horticulture'' 8: 49)<ref>W., “An Account of the Lowell Cemetery, Its Situation, Historical Associations, and Particular Description,” ''Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs'' 8, no. 2 (February 1842): 47–50, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/UKZS86F6 view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“The site of the Lowell Cemetery is eminently '''picturesque''' and beautiful. The northern and southern boundaries embrace a range of high grounds, covered for the most part with a young and verdant growth of trees: these high grounds gradually and abruptly slope towards the centre or valley, through which runs a brook, supplying several large [[pond]]s for the season, also sufficient for supplying a [[fountain]] of about one hundred feet head. The southern range of high grounds is covered with a verdant growth of trees, and is highly ornamented with that most characteristic and appropriate of all sepulchral ornaments—well grown and stately oaks, intermixed with the funereal and feathered boughs of the dark hemlock; while the [[slope]]s are only partially clothed with trees, and the contrast between the deep dusky green of the hemlock and the soft bright tint of the grass in the open spaces between them, produces an effect almost magical, and which strikes one as being more the result of art than nature.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | of | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | and | ||

| − | |||

| − | the | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | the | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Barber, John Warner and Henry Howe, 1844, describing Mount Holly, NJ (1844: 113)<ref>John Warner Barber, and Henry Howe, ''Historical Collections of the State of New Jersey. . . with Geographical Descriptions of Every Township in the State'' (Newark, NJ: Benjamin Olds, 1844), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/KBBHZ5NT/ view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“There are in the village several elegant dwellings, among which is conspicuous Dunn’s [[Chinese manner|Chinese]] cottage, erected by the proprietor of the late [[Chinese manner|Chinese]] and [[English style|English]] cottage style. The grounds are tastefully arranged, and the general effect of the whole is light, fanciful, and extremely '''picturesque'''.” | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | [[File:0357.jpg|thumb|Fig. 12, [[Alexander Jackson Davis]], “Montgomery Place,” in [[Andrew Jackson Downing|A. J. Downing]], ed., ''Horticulturist'' 2, no. 4 (October 1847): pl. opp. 153.]] | |

| − | + | *[[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing, Andrew Jackson]], October 1847, “A Visit to Montgomery Place,” describing [[Montgomery place|Montgomery Place]], country home of Mrs. Edward (Louise) Livingston, Dutchess County, NY (''Horticulturist'' 2: 157)<ref>Alexander Jackson Downing, ed., “A Visit to Montgomery Place,” ''Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste'' 2, no. 4 (October 1847): 153–60, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/XUWRREQS view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“He takes another path, passes by an airy looking [[rustic style|rustic]] [[bridge]], and plunging for a moment into the [[thicket]], emerges again in full [[view]] of the first [[cataract]]. Coming from the solemn depths of the [[wood]]s, he is astonished at the noise and volume of the stream, which here rushes in wild foam and confusion over the rocky [[Fall/Falling_garden|fall]], forty feet in depth. Ascending a flight of steps made in the precipitous banks of the stream, we have another [[view]], which is scarcely less spirited and '''picturesque'''. | |

| − | + | :“This [[waterfall]], beautiful at all seasons, would alone be considered a sufficient attraction to give notoriety to a rural locality in most country neighborhoods. But as if nature had intended to lavish her gifts here, she has, in the course of this valley, given two other [[cataract]]s. These are all striking enough to be worthy of the pencil of the artist, and they make this valley a feast of wonders to the lovers of the '''picturesque'''.” [Fig. 12] | |

| − | |||

| − | of | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *<div id="Miller"></div>Miller, Lewis, June 5, 1849, describing [[Mount Vernon]], [[plantation]] of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (c. 1850: 108)<ref>Lewis Miller, ''Orbis Pictus: A Picturesque Album to the Ladies of York, Pennsylvania'' (Williamsburg, VA: Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1850), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/XNQR79ST view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“[[Mount Vernon]]. . . is pleasantly situated on the Virginia bank of the river. The mansion house itself appears venerable and convenient[.] A lofty [[portico]] ninety-six feet in length, Supported by Eight [[pillar]]s, has a pleasing effect when viewed from the water: ornamented with little [[copse]]s— [[clump]]s, and Single trees—. add a romantick and '''picturesque''' appearance to the whole Scenery.” [Fig. 3] [[#Miller|back up to History]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | the | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | has | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[File:0288.jpg|thumb|Fig. 13, George Cooke (artist), W. J. Bennett (engraver), ''Richmond, From the Hill Above the Waterworks'', 1834.]] | |

| − | + | *Committee on the Capitol [[Square]], Richmond City Council, July 24, 1851, describing John Notman’s plans for the Capitol [[Square]], Richmond, VA (quoted in Greiff 1979: 162)<ref>Constance Greif, ''John Notman, Architect, 1810–1865'' (Philadelphia: Athenaeum of Philadelphia, 1979), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/SXT2RI6Z view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| + | :“It was deemed advisable to commence the improvements of the [[Square]] itself on the western side thereof. . . the ground on that side [has been] formed into gentle natural undulations, rising gradually to the base of the capitol and to the monument. . . giving great apparent extent to the grounds and producing an agreeable variety and at the same time affording space for much greater extent of [[walk]]s, leading in every direction where they may be useful or agreeable without the necessity of climbing steps and dividing the grounds into irregular and '''picturesque''' [[lawn]]s.” [Fig. 13] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Horticola [pseud.], March 1852, “Notes on Gardens and Country Seats Near Boston,” describing Oakley Place, seat of William Pratt, Boston, MA (''Horticulturist'' 7: 127)<ref>Horticola [pseud.], “Notes on Gardens and Country Seats near Boston,” ''Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste'' 7, no. 3 (March 1852): 126–28, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/73G5WK8I view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“OAKLEY PLACE, ''the residence of'' Mrs. PRATT, is near Mr. CUSHING’S, and presents a fine specimen of a small country place, combining the '''picturesque''' and the natural—the [[gardenesque]] and the wild, in beautiful harmony together.” | |

| − | + | ===Citations=== | |

| − | + | *Whately, Thomas, 1770, ''Observations on Modern Gardening'' (1770; repr., 1982: 146–47)<ref>Thomas Whately, ''Observations on Modern Gardening'', 3rd ed. (1770; repr., London: Garland, 1982), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/QKRK8DCD view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“Of '''PICTURESQUE''' BEAUTY. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“XLVII. But regularity can never attain to a great share of beauty, and to none of the species called '''''picturesque'''''; a denomination in general expressive of excellence, but which, by being too indiscriminately applied, may be sometimes productive of errors. That a subject is recommended at least to our notice, and probably to our favour, if it has been distinguished by the pencil of an eminent painter, is indisputable; we are delighted to see those objects in the reality, which we are used to admire in the representation; and we improve upon their intrinsic merit, by recollecting their effects in the picture. The greatest beauties of nature will often suggest the remembrance; for it is the business of a landskip painter to select them; and his choice is absolutely unrestrained; he is at liberty to exclude all objects which may hurt the composition; he has the power of combining those which he admits in the most agreable manner; he can even determine the season of the year, and the hour of the day, to shew his landskip in whatever light he prefers. The works therefore of a great master, are fine exhibitions of nature, and an excellent school wherein to form a taste for beauty; but still their authority is not absolute; they must be used only as studies, not as models; for a picture and a scene in nature, though they agree in many, yet differ in some particulars, which must always be taken into consideration, before we can decide upon the circumstances which may be transferred from the one to the other. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“In their ''dimensions'' the distinction is obvious; the same objects on different scales have very different effects; those which seem monstrous on the one, may appear diminutive on the other; and a form which is elegant in a small object, may be too delicate for a large one.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Gilpin, William, 1792, ''Three Essays: On Picturesque Beauty'' (1792: 3–8)<ref>William Gilpin, ''Three Essays: On Picturesque Beauty; On Picturesque Travel; and On Sketching Landscape: To Which Is Added a Poem on Landscape Painting'' (1792; repr., Farnborough, England: Gregg, 1972), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/JT6TGTT3 view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“Disputes about beauty might perhaps be involved in less confusion, if a distinction were established, which certainly exists, between such objects as are ''beautiful'', and such as are '''''picturesque'''''—between those, which please the eye in their natural state; and those, which please from some quality, capable of being ''illustrated in painting''. . . | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“In examining the ''real object'', we shall find, one source of beauty arises from that species of elegance, which we call ''smoothness'', or ''neatness''; for the terms are nearly synonymous. . . | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“But in '''''picturesque''''' ''representation'' it seems somewhat odd, yet we shall perhaps find it equally true, that the reverse of this is the case; and that the ideas of ''neat'' and ''smooth'', instead of being '''''picturesque''''', in fact disqualify the object, in which they reside, from any pretensions to '''''picturesque''''' beauty.—Nay farther, we do not scruple to assert, that ''roughness'' forms the most essential point of difference between the ''beautiful'', and the '''''picturesque'''''; as it seems to be that particular quality, which makes objects chiefly pleasing in painting.—I use the general term ''roughness''; but properly speaking roughness relates only to the surfaces of bodies: when we speak of their delineation, we use the word ''ruggedness''. Both ideas however equally enter into the '''picturesque'''; and both are observable in the smaller, as well as in the larger parts of nature—in the outline, and bark of a tree, as in the rude summit, and craggy sides of a mountain. . . | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | the picturesque and the | ||

| − | and the | ||

| − | + | :“Turn the [[lawn]] into a piece of broken ground: plant rugged oaks instead of flowering [[shrub]]s: break the edges of the [[walk]]: give it the rudeness of a road: mark it with wheel-tracks; and scatter around a few stones, and brushwood; in a word, instead of making the whole ''smooth'', make it ''rough''; and you make it also '''''picturesque'''''.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Price, Uvedale, 1794, ''An Essay on the Picturesque'' (1794: 17, 34)<ref>Uvedale Price, ''Essays on the Picturesque as Compared with the Sublime and the Beautiful'' (London: J. Robson, 1794), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/XH6SS7T2 view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“IT seems to me, that the neglect, which prevails in the works of modern improvers, of all that is '''picturesque''', is owing to their exclusive attention to high polish and flowing lines, the charms of which they are so engaged in contemplating, as to make them overlook two of the most fruitful sources of human pleasure; the first, that great and universal source of pleasure, variety, whole power is independent of beauty, but without which even beauty itself soon ceases to please; the other, intricacy, a quality which, though distinct from variety, is so connected and blended with it, that the one can hardly exist without the other. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“THERE are few words whose meaning has been less accurately determined than that of the word '''Picturesque'''.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Anonymous, 1798, ''Encyclopaedia'' (1798: 7:565)<ref>''Encyclopaedia, or A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Miscellaneous Literature'', 18 vols. (Philadelphia: Thomas Dobson, 1798), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/F6T8DNDF view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | :“II. '''PICTURESQUE''' BEAUTY. Though the aids of art are as essential to gardening, as education is to manners; yet art may do too much: she ought to be considered as the hand-maid, not as the mistress, of nature; and whether she be employed in carving a tree into the figure of an animal, or in shaping a [[view]] into the form of a picture, she is equally culpable. The nature of the place is sacred. Should this tend to landscape, form some principal point of [[view]], assist nature and perfect it; provided this can be done without injuring the [[view]]s from other points. But do not disfigure the natural features of the place:—do not sacrifice its native beauties, to the arbitrary laws of landscape painting. . . | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“Instead of sacrificing the natural beauties of the place to one formal landscape, let every step disclose fresh charms unsought for. ''Planting and Gardening'', p. 602.” | |

| − | one | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *<div id="Gregory"></div>[[G. (George) Gregory|Gregory, G. (George)]], 1816, ''A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences'' (1816: 2:n.p.)<ref>George Gregory, A ''New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences'', 1st American ed., 3 vols. (Philadelphia: Isaac Peirce, 1816), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/2H8KAZ5E view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“GARDENING. This art, so natural to man, so improving to health, so conducive to the comforts and the best luxuries of life, may properly be divided into two branches; practical, and '''picturesque''' or [[landscape gardening]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“The former is what every person, except the inhabitants of populous cities, has more or less occasion to practise; the latter is a privilege which only the very opulent can enjoy, and which must consequently be the elegant amusement of a chosen few. | |

| − | + | :“'''Picturesque''' or [[landscape gardening]] should certainly never be attempted on a small scale. Indeed we are not certain that we may not be incurring a solecism in applying the term gardening to this department of agriculture. It is properly the art of laying out grounds; and the [[park]] or the farm, not the garden, is its object. It never can be attempted with success on a smaller scale than 20 acres; but 50 or 100, or even more, are better adapted to the design. | |

| − | + | :“That style of gardening which would unite both objects, and which would give a '''picturesque''' effect to an acre or two of ground, is truly absurd. Many an improvident citizen wastes unprofitably the morsel of earth which should grow cabbages for his family, on an unprofitable grass-[[plat]] or [[shrubbery]], on serpentines and mazes, and fishponds; or even on [[cascade]]s, to the infinite annoyance of his visitors, the prejudice of his own health, and the merriment of all persons of true taste. This mania for the '''picturesque''' would have been not less deserving the ridicule of an Addison, than the perverse taste which displayed our first parents in yew, and the Graces and Muses in Portugal laurel. . . | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | of | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“'''Picturesque''' gardening is effected by a number of means which a true rural genius, and the study of examples, only can produce. These examples may be pictures, but the better instructors will be scenes in nature; and the proper grouping of trees, according to their mode of growth, shades of green, and appearance in autumn, will effect a great deal. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“To plant '''picturesquely''', a knowledge of the characteristic differences of trees and [[shrub]]s, is evidently a principle qualification. Some trees spread their branches wide, others grow spiral, and some conical; some have a close foliage, others an open one; and some form regular, others irregular heads, the branches and leaves of which may grow erect, level, or pendant.” [[#Gregory_cite|back up to History]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *<div id="Loudon"></div>[[J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon|Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius)]], 1826, ''An Encyclopaedia of Gardening'' (1826: 1000)<ref>J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, ''An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening'', 4th ed. (London: Longman et al., 1826), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/KNKTCA4W view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Gardening, | ||

| − | + | :“7180. ''As an illustration of the theory of [[landscape gardening|landscape-gardening]]'', which we have adopted, we subjoin a slight analysis of the principles of a composition, expressive of '''picturesque''' and natural beauty. For this purpose, it is a matter of indifference, as far as respects '''picturesque''' beauty, whether we choose a real or painted landscape; but, as we mean also to investigate its poetic or general beauty, we shall prefer a reality. We choose then a perfect flat, varied by [[wood]], say elms, with a piece of water, and a high [[wall]], forming the angle of a ruined building; it is animated by cows and sheep; its expression is that of melancholy grandeur; and, independently of this beauty, it is '''picturesque''' in expression; that is, if painted it would form a tolerable picture.” [[#Loudon_cite|back up to History]] | |

| − | of | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *[[André Parmentier|Parmentier, André]], 1828, ''The New American Gardener'' (quoted in Fessenden 1828: 185)<ref>Thomas Fessenden, ''New American Gardener'' (Boston: J. B. Russell, 1828), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/M8WDX2P7 view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“For where can we find an individual, sensible to the beauties and charms of nature, who would prefer a ''symmetric'' garden to one in modern taste; who would not prefer to [[walk]] in a [[plantation]] irregular and '''picturesque''', rather than in those straight and monotonous [[alley]]s, bordered with mournful box, the resort of noxious insects?” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | to | ||

| − | the | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Anonymous, January 4, 1828, “Rural Scenery” (''New England Farmer'' 6: 187)<ref>Anonymous, “Rural Scenery,” ''New England Farmer'' 6, no. 24 (January 4, 1828): 187, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/INS7XKSI view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“''Landscape and'' '''''Picturesque''''' ''Gardens''.—Among the embellishments which attend the increase of wealth, the cultivation of the sciences, and the refinement of taste, none diversify and heighten the beauty of rural scenery, more than '''picturesque''' and landscape gardens. . . | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | and | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“For the introduction into this country of the design and execution of landscape and '''picturesque''' gardening, the public is much indebted to [[André Parmentier|Mr. A. Parmentier]], proprietor of the [[Parmentier’s Horticultural and Botanical Garden|Horticultural Botanic Garden]], near Brooklyn, two miles from this city. His own garden, for which he made so advantageous a choice, may give us some idea of his taste. The [[border]]s are composed of every variety of trees and [[shrub]]s that are found in his nurseries. The [[walk]]s are sinuous, adapted to the irregularity of the ground, and affording to visitors a continual change of scenery, which is not enjoyed in gardens laid out in even surfaces, and in right lines. His dwelling and French saloon are in accordance with the surrounding rural aspect. In his gardens are 25,000 vines planted and arranged in the manner of the vineyards of France.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Dearborn, H. A. S., September 19, 1829, ''An Address Delivered Before the Massachusetts Horticultural Society'' (1833: 16)<ref>H.A.S. (Henry Alexander Scammell) Dearborn, ''An Address Delivered before the Massachusetts Horticultural Society'' (Boston: J. T. Buckingham, 1833), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/KTVETNFP view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | :“The natural divisions of Horticulture are the [[Kitchen Garden]], Seminary, [[Nursery]], Fruit Trees and Vines, Flowers and [[Green Houses]], the [[botanic garden|Botanical]] and Medical Garden, and [[landscape gardening|Landscape]], or '''Picturesque''' Gardening.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Anonymous, | + | *<div id="Register"></div>Anonymous, April 1, 1837, “Landscape Gardening” (''Horticultural Register'' 3: 124–25)<ref>Anonymous, “Landscape Gardening,” ''Horticultural Register, and Gardener’s Magazine'' 3 (April 1, 1837): 121–31, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/TBFISAR7 view on Zotero].</ref> |

| − | ( | ||

| − | + | :“Confining ourselves to the [[modern style|modern]] or [[natural style]], we shall proceed to offer some remarks on its characteristics. Landscape gardens in this style generally present either '''picturesque''', or what is termed [[gardenesque]] scenery. '''Picturesque''' scenery is a facsimile imitation of natural scenery; the trees and [[shrub]]s constituting it are planted, as in natural forests and forest-groups, such as a painter would wish to copy; every appearance of art is concealed, and it exactly resembles a real landscape, except in the greater variety and profusion of pleasing assemblages within a smaller space than can be found in nature. Its effect as a ''whole'', only, is studied. . . The '''picturesque''' is calculated to please particularly the admirers of landscape scenery in nature; the [[gardenesque]] not only these, but the florist and botanist also. . . In '''picturesque''' scenery, the trees may be allowed to grow thick or irregular, provided they form an agreeable collective effect; but in the [[gardenesque]], every thing irregular or rough should be removed, which would prevent a neat and finished appearance.” [[#Register_cite|back up to History]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | and the | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

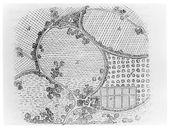

| − | + | [[File:1761.jpg|thumb|Fig. 14, [[J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon|J. C. Loudon]], Trees arranged in the picturesque style, in ''The Suburban Gardener'' (1838), 165, fig. 48.]] | |

| − | + | *[[J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon|Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius)]], 1838, ''The Suburban Gardener'' (1838: 164–66)<ref>J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, ''The Suburban Gardener, and Villa Companion'' (London: Longman et al., 1838), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/BQVBJ48F view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | :“'''''Picturesque''''' ''Imitation''. To design and execute a scene in either of these styles of imitative art, the artist would require to have the eye of a landscape-painter; to a certain extent, the science of an architect and of a botanist; and the knowledge of a horticulturist. Every part of nature, whether rude or refined, may be imitated according to art. For example, an old gravel pit, which had become covered with bushes and indigenous trees, and contained a hovel or rude cottage in the bottom, with a natural path worn in the grass by the occupants, would be improved according to imitative art, if foreign trees, [[shrub]]s, and plants, even to the grasses, were introduced instead of indigenous ones; and a Swiss cottage, or an architectural cottage of any kind that would not be recognised as the common cottage of the country, substituted for the hovel. To complete the character of art, the [[walk]] should be formed and gravelled, at least, to such an extent as to prevent its being mistaken for a natural path. Rocky scenery, aquatic scenery, dale or dingle scenery, forest scenery, [[copse]] scenery, and open glade scenery, may all be imitated on the same principle; viz. that of substituting foreign for indigenous vegetation, and laying out artificial [[walk]]s. This is sufficient to constitute a '''picturesque''' imitation of natural scenery. . . | |

| − | |||

| − | and | ||

| − | and | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“In ''fig''. 47. the trees are arranged in the [[gardenesque]] manner; and in ''fig''. 48., in the '''picturesque''' style. The same character is also communicated to the [[walk]]s; that in the [[gardenesque]] style, having the margins definite and smooth, while the '''picturesque''' [[walk]] has the edge indefinite and rough. Utility requires that the gravel, in both styles of [[walk]], should be smooth, firm, and dry; for it must always be borne in mind, that, as landscape-gardening is a useful as well as an agreeable art, no beauty must ever be allowed to interfere with the former quality. [Fig. 14] | |

| − | |||

| − | + | :“In planting, thinning, and pruning, in order to produce [[gardenesque]] effect, the beauty of every individual tree and [[shrub]], as a single object, is tobe taken into consideration, as well as the beauty of the mass: while in planting, thinning, and pruning for '''picturesque''' effect, the beauty of individual trees and [[shrub]]s is of little consequence; because no tree or [[shrub]], in a '''picturesque''' [[plantation]] or scene, should stand isolated, and each should be considered as merely forming part of a group or mass. In a '''picturesque''' imitation of nature, the trees and [[shrub]]s, when planted, should be scattered over the ground in the most irregular manner; both in their disposition with reference to their immediate effect as plants, and with reference to their future effect as trees and [[shrub]]s. In some places trees should prevail, in others [[shrub]]s; in some parts the [[plantation]] should be thick, in others it should be thin; two or three trees, or a tree and [[shrub]], ought often to be planted in one hole, and this more especially on [[lawn]]s.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | and | ||

| − | the | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | picturesque | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *[[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing, Andrew Jackson]], 1844, Excerpt from ''A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America; . . . '' (1844: 102)<ref>A. J. Downing, ''A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America; with a View to the Improvement of Country Residences. . . with Remarks on Rural Architecture'', 2nd ed. (New York: Wiley and Putnam, 1844), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/IGJXRU9V view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :"In fig. 25, is shown a small piece of ground, on one side of a cottage, in which a '''picturesque''' character is attempted to be maintained. The [[plantation]]s here, are made mostly with shrubs instead of trees, the latter being only sparingly introduced, for the want of room. In the disposition of these shrubs, however, the same attention to '''picturesque''' effect is paid as we have already pointed out in our remarks on grouping ; and by connecting the [[thicket]]s and groups here and there, so as to conceal one [[walk]] from the other, a surprising variety and effect will frequently be produced, in an exceedingly limited spot." | |

| − | + | *[[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing, Andrew Jackson]], February 1848, “Hints and Designs for Rustic Buildings” (''Horticulturist'' 2: 363–64)<ref>Anonymous, “Hints and Designs for Rustic Buildings,” ''Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste'' 2, no. 8 (February 1848): 363–65, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/4H34XQXX view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | on | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“But the more humble and simple cottage grounds, the rural [[walk]]s of the [[ferme ornée]], and the modest garden of the suburban amateur, have also their ornamental objects and rural buildings—in their place, as charming and spirited as the more artistical embellishments which surround the palladian villa. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | the | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | the | ||

| − | + | :“These are the [[seat]]s, [[bower]]s, [[grotto]]es, and [[arbor]]s, of [[rustic style|rustic]] work—than which nothing can be more easily and economically constructed, nor can add more to the rural or '''picturesque''' expression of the scene. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“Those simple buildings, often constructed only of a few logs and twisted limbs of trees, are in good keeping with the simplest or the grandest forms of nature. . . . The terminus of a long [[walk]], otherwise unmeaning, is in no way more easily rendered satisfactory and agreeable, than by a '''picturesque''' place of repose; and the charms of a commanding hill, where the eye wanders over a grand panorama, is rarely so happily improved, as by being crowned with a [[rustic style|rustic]] [[pavilion]], which seems as the shelter and resting place of modern Gilpins, ‘in search of the picturesque.’” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Elder, Walter, 1849, ''The Cottage Garden of America'' (1849: 26)<ref>Walter Elder, ''The Cottage Garden of America'' (Philadelphia: Moss, 1849), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/NNC7BTFT view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“If [the rich gentleman’s [[lawn]] is constructed] in the '''picturesque''' style, the trees will stand in groups, contrasting the sizes and colours of their foliage, commingling, and making a harmonious whole.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[File:0354.jpg|thumb|Fig. 15, Anonymous, “Example of the Picturesque in Landscape Gardening,” in [[Andrew Jackson Downing|A. J. Downing]], ''A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening'', 4th ed. (1849), pl. opp. 273, fig. 16.]] | |

| − | + | *<div id="Downing"></div>[[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing, A. J.]], 1849, ''A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening'' (1849; repr., 1991: 63, 69, 74, 142, 182, 193, 270, 352, 443–44)<ref>Andrew Jackson Downing, ''A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America'', 4th ed. (1849; repr., Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1991), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/K7BRCDC5 view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“The earliest professors of Modern [[Landscape Gardening]] have generally agreed upon two variations, of which the art is capable. . . These are the ''beautiful'' and the '''''picturesque''''': or, to speak more definitely, the beauty characterized by simple and flowing forms, and that expressed by striking, irregular, spirited forms. . . | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“More concisely, the Beautiful is nature or art obeying the universal laws of perfect existence (i.e. Beauty), easily, freely, harmoniously, and without the ''display'' of power. The '''Picturesque''' is nature or art obeying the same laws rudely, violently, irregularly, and often displaying power only. . . | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“THE '''PICTURESQUE''' in [[Landscape Gardening]]. . . aims at the production of outlines of a certain spirited irregularity, surfaces comparatively abrupt and broken, and growth of a somewhat wild and bold character. The shape of the ground sought after, has its occasional smoothness varied by sudden variations, and in parts runs into dingles, rocky groups, and broken banks. The trees should in many places be old and irregular. . . [Fig. 15] | |

| − | + | [[File:0375.jpg|thumb|Fig. 16, Anonymous, “Grouping to produce the Picturesque,” in [[Andrew Jackson Downing|A. J. Downing]], ''A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening'', 4th ed. (1849),103, fig. 22.]] | |