Difference between revisions of "J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon"

C-tompkins (talk | contribs) |

C-tompkins (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 266: | Line 266: | ||

| − | * 1826, ''An Encyclopaedia of Gardening'' (pp. 942–43 | + | * 1826, ''An Encyclopaedia of Gardening'' (pp. 942–43) <ref name="Loudon_1826"></ref> |

:“6811. In regard to ''extent'', the least is a group (''fig''. 628. ''e'' and ''d''), which must consist at least of two plants; larger, it is called a [[thicket]] (''b c''); round and compact, it is called a [[clump]] (''a''); still larger, a mass; and all above a mass is denominated a [[wood]] or forest, and characterised by comparative degrees of largeness. The term ''[[wood]]'' may be applied to a large assemblage of trees, either natural or artificial; forest, exclusively to the most extensive or natural assemblages. . . . | :“6811. In regard to ''extent'', the least is a group (''fig''. 628. ''e'' and ''d''), which must consist at least of two plants; larger, it is called a [[thicket]] (''b c''); round and compact, it is called a [[clump]] (''a''); still larger, a mass; and all above a mass is denominated a [[wood]] or forest, and characterised by comparative degrees of largeness. The term ''[[wood]]'' may be applied to a large assemblage of trees, either natural or artificial; forest, exclusively to the most extensive or natural assemblages. . . . | ||

| − | :“6813. ''With respect to the disposition of the trees within the [[plantation]]'', they may be placed regularly in rows, squares, parallelograms, or quincunx; irregularly in the manner of groups; without undergrowths, as in ''[[grove]]s'' (''fig''. 629. ''a'', ''b''); with undergrowths, as in ''[[woods]]'' (''c''); all undergrowths, as in ''copse-[[woods]]'' (''d''). Or they may form ''[[avenue]]s'' (''fig''. 630. ''a''); double [[avenue]]s (''b''); [[avenue]]s intersecting in the manner of a Greek cross (''c''); of a martyr’s cross (''d''); of a star (''e'') or of a cross patée, or duck’s foot (''patée d’oye'') (''f''). | + | :“6813. ''With respect to the disposition of the trees within the [[plantation]]'', they may be placed regularly in rows, squares, parallelograms, or quincunx; irregularly in the manner of groups; without undergrowths, as in ''[[grove]]s'' (''fig''. 629. ''a'', ''b''); with undergrowths, as in ''[[woods]]'' (''c''); all undergrowths, as in ''copse-[[woods]]'' (''d''). Or they may form ''[[avenue]]s'' (''fig''. 630. ''a''); double [[avenue]]s (''b''); [[avenue]]s intersecting in the manner of a Greek cross (''c''); of a martyr’s cross (''d''); of a star (''e'') or of a cross patée, or duck’s foot (''patée d’oye'') (''f'')." |

| + | |||

| + | * 1826, ''An Encyclopaedia of Gardening'' (pp. 950, 952) <ref name="Loudon_1826"></ref> | ||

| + | :“6853. ''The situations'' [of [[plantation]]s] to be planted, with a view to effect, necessarily depends on the kind of effect intended; these may reduced to three—to give beauty and variety to general scenery, as in forming [[plantation]]s here and there throughout a demesne; to give form and character to a country-residence, as in planting a [[park]] and [[pleasure ground|pleasure-grounds]]; and to create a particular and independent beauty or effect, as in planting an extensive area or [[wood]], unconnected with any other object, and disposing of the interior in [[avenue]]s, glades, and other forms. . . . | ||

| + | |||

| + | :“6855. The outline of [[plantation]]s, made with a view to the composition of a country-residence, is guided by the same general principles; whether the trees are to be disposed in regular forms, avowedly artificial; or in irregular forms, in imitation of nature. . . . The first thing is, in both modes, to compose a principal mass, from which the rest may appear to proceed; or be, or seem to be, connected.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | * 1826, ''An Encyclopaedia of Gardening'' (p. 965) <ref name="Loudon_1826"></ref> | ||

:“6923. ''Ornamental plantations'' are no less frequently neglected than such as are considered chiefly useful. [[Clump]]s, belts, and screens which have become thin, because they have not been thinned, are almost every where to be met with. ‘In those neglected [[plantation]]s,’ says Lord Meadowbank, ‘where daylight may be seen for miles, through, naked stems, chilled and contracted by the cold, the mischief might, perhaps, be partially remedied, by planting young trees round the extremities, which, having room to spread luxuriantly, would exclude the winds, and the internal spaces might be thickened up with oak, silver firs, beeches, and such other trees as thrive with a small portion of light. When once the wind is excluded, the weakest of the old trees might be taken out, and the others left to profit by the shelter and space that is afforded.’ (''Life of Lord Kaimes, by Tytler''.) One of the most hopeless cases of improvement in this department is that of an old [[clump]] of Scotch pines . . . from which scarcely any trees can be taken without risking the failure of the remainder. The only way is to add to it, either by some scattered groups in one direction, or in various directions. Where a [[clump]] consists of a hard [[wood]], either entirely or in part, it may sometimes, if effect permits, be reduced to a group, by gradually reducing the number of the trees. The group left should be composed of two or three trees of at least two species, different in bulk, and some what in habit, in order that the combined mass may not have the formality of the [[clump]].” [Fig. 4] | :“6923. ''Ornamental plantations'' are no less frequently neglected than such as are considered chiefly useful. [[Clump]]s, belts, and screens which have become thin, because they have not been thinned, are almost every where to be met with. ‘In those neglected [[plantation]]s,’ says Lord Meadowbank, ‘where daylight may be seen for miles, through, naked stems, chilled and contracted by the cold, the mischief might, perhaps, be partially remedied, by planting young trees round the extremities, which, having room to spread luxuriantly, would exclude the winds, and the internal spaces might be thickened up with oak, silver firs, beeches, and such other trees as thrive with a small portion of light. When once the wind is excluded, the weakest of the old trees might be taken out, and the others left to profit by the shelter and space that is afforded.’ (''Life of Lord Kaimes, by Tytler''.) One of the most hopeless cases of improvement in this department is that of an old [[clump]] of Scotch pines . . . from which scarcely any trees can be taken without risking the failure of the remainder. The only way is to add to it, either by some scattered groups in one direction, or in various directions. Where a [[clump]] consists of a hard [[wood]], either entirely or in part, it may sometimes, if effect permits, be reduced to a group, by gradually reducing the number of the trees. The group left should be composed of two or three trees of at least two species, different in bulk, and some what in habit, in order that the combined mass may not have the formality of the [[clump]].” [Fig. 4] | ||

| Line 280: | Line 288: | ||

| − | * 1826, ''An Encyclopaedia of Gardening'' (pp. 994-96 | + | * 1826, ''An Encyclopaedia of Gardening'' (pp. 994-96) <ref name="Loudon_1826"></ref> |

:“7156. ''In [[landscape gardening]]'', the art of the gardener is directed to different objects, and some of them of a higher kind than any belonging to gardening as an art of culture. In the three branches [of gardening] hitherto considered, art is chiefly employed in the cultivation of plants, with a view of obtaining their products; but in the branch now under consideration, art is exercised in disposing of ground, buildings, and water, as well as the vegetating materials which enter into the composition of verdant landscape. This is, in a strict sense, what is called [[landscape gardening|landscape-gardening]], or the art of creating or improving landscapes; but as landscapes are seldom required to be created for their own sakes, [[landscape gardening|landscape-gardening]], as actually practised, may be defined, ‘the art of arranging the different parts which compose the external scenery of a country-residence, so as to produce the different beauties and conveniences of which that scene of domestic life is susceptible.’ . . . | :“7156. ''In [[landscape gardening]]'', the art of the gardener is directed to different objects, and some of them of a higher kind than any belonging to gardening as an art of culture. In the three branches [of gardening] hitherto considered, art is chiefly employed in the cultivation of plants, with a view of obtaining their products; but in the branch now under consideration, art is exercised in disposing of ground, buildings, and water, as well as the vegetating materials which enter into the composition of verdant landscape. This is, in a strict sense, what is called [[landscape gardening|landscape-gardening]], or the art of creating or improving landscapes; but as landscapes are seldom required to be created for their own sakes, [[landscape gardening|landscape-gardening]], as actually practised, may be defined, ‘the art of arranging the different parts which compose the external scenery of a country-residence, so as to produce the different beauties and conveniences of which that scene of domestic life is susceptible.’ . . . | ||

Revision as of 21:31, December 10, 2014

Sites

Terms

Texts

An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826)

- 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (pp. 26–27) [1]

- “115. The Dutch are generally considered as having a particular taste in gardening, yet their gardens, Hirschfeld observes, appear to differ little in design from those of the French. The characteristics of both are symmetry and abundance of ornaments. The only difference to be remarked is, that the gardens of Holland are more confined, more covered with frivolous ornaments, and intersected with still, and often muddy pieces of water. . . .

- “116. Grassy slopes and green terraces and walks are more common in Holland than in any other country of the continent, because the climate and soil are favourable for turf; and these verdant slopes and mounds may be said to form, with their oblong canals, the characteristics of the Dutch style of laying out grounds.”

- 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (p. 103) [1]

- “478. A plan of a Chinese garden and dwelling. . . . If this plan . . . is really correct, it seems to countenance the idea of the modern style being taken from that of the Chinese. . . . [Fig. 10]

- 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (p. 105) [1]

- “482. . . .

- “The first work after a settlement [in North America] is to plant a peach and apple orchard, placing the trees alternately. The peach, being short-lived, is soon removed, and its place covered by the branches of the apple-trees."

- 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (p. 106) [1]

- “486. Forest trees. . . . From the Transactions of the Society of Agriculture of New York, we learn, that hawthorn hedges and other live fences are generally adopted in the cultivated districts; but the time is not yet arrived for forming timber-plantations."

- 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (p. 296) [1]

- “1501. The basket-edging (fig. 219.) is a rim or fret of iron-wire, and sometimes of laths; formed, when small, in entire pieces, and when large, in segments. Its use is to enclose dug spots on lawns, so that when the flowers and shrubs cover the surface, they appear to grow from, or give some allusion to, a basket. These articles are also formed in cast-iron, and used as edgings to beds and plots, in plant-stoves and conservatories.

- “1502. The earthenware border . . . is composed of long narrow plates of common tile-clay, with the upper edge cut into such shapes as may be deemed ornamental. They form neat and permanent edgings to parterres; and are used more especially in Holland, as casings, or borderings to beds of florists’ flowers. [Fig. 5]

- “1503. Edgings of various sorts are formed of wire, basket-willows, laths, boards, plate-iron, and cast-iron; the last is much the best material."

- 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (pp. 308–9) [1]

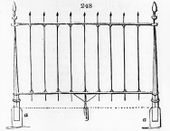

- “1576. Espalier rails are substitutes for walls, and which they so far resemble, that trees are regularly spread and trained along them, are fully exposed to the light, and having their branches fixed are less liable to be injured by high winds. They are formed of wood, cast-iron, or wire and wood.

- “1577. The wooden espalier, of the simplest kind, is merely a straight row of stakes driven in the ground at six or eight inches asunder, and four or five feet high, and joined and kept in a line at top by a rail of wood, or iron hoop, through which one nail is driven into the heart of each stake. . . .

- “1578. The framed wooden espalier rail is composed of frames fitted with vertical bars at six or eight inches asunder, which are nailed on in preference to mortising, in order to preserve entire the strength of the upper and lower rails. . . .

- “1579. The cast-iron espalier rail . . . resembles a common street railing, but it is made lighter. . . . [Fig. 5]

- “1580. The horizontal espalier rail . . . is a frame of wood or iron, of any form or magnitude, and either detached or united, fitted in with bars, and placed horizontally, at any convenient distance from the ground. . . . [Fig. 6]

- “1581. The oblique espalier rail is composed of bars, wires, or lattice-work, placed obliquely.”

- “1582. Of fixed structures, the brick wall, both as a fence, and retainer of heat, may be reckoned essential to every kitchen-garden; and in many cases the mode of building them hollow may be advantageously adopted."

- 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (pp. 310–15) [1]

- “1584. Green-houses were known in this country in the seventeenth century. They were then, and continued to be, in all probability, till the beginning of the 18th century, mere chambers distinguished by more glass windows in front than were usual in dwelling-rooms. Such was the green-house in the apothecaries’ garden at Chelsea. . . .

- “1585. The first æra of improvement may be dated 1717, when Switzer published a plan for a forcing-house, suggested by the Duke of Rutland’s graperies at Belvoir Castle. Miller, Bradley, and others, now published designs, in which glass roofs were introduced. . . .

- “1586. A second æra of improvement may be dated from the time when Dr. Anderson published a treatise on his patent hot-house, and from the publication of Knight’s papers in the Horticultural Society’s Transactions, both of which happened about 1809. Not that the scheme of Dr. Anderson ever succeeded, or is at all likely to answer to the extent imagined by its inventor; but the philosophical discussion connected with its description and uses, excited the attention of some gardeners, as did the remarks of Knight on the proper slope of glass roofs (Hort. Trans. vol. i.); and both contributed, there can be no doubt, to produce the patent hot-houses of Stewart and Jorden, and other less known improvements. These, though they may now be considered as reduced au merite historique, yet were really beneficial in their day. Knight’s improvements chiefly respected the angle of the glass roof; a subject first taken up by Boerhaave about a century before, adopted by Linnaeus (Amen. Acad. i. 44.), and subsequently enlarged on by Faccio in 1699, Adanson (Familles des Plantes, tom, i.) in 1763, Miller in 1768, Speechley in 1789, John Williams of New York (Tr. Ag. Soc. New York, 2d edit.) in 1801, Knight in 1806, and by some intermediate authors whom it is needless to name.

- “1587. The last and most important æra is marked by the fortunate discovery of Sir G. Mackenzie in 1815, ‘that the form of glass roofs best calculated for the admission of the sun’s rays is a hemispherical figure.’

- “1591. . . . The object or end of hot-houses is to form habitations for vegetables, and either for such exotic plants as will not grow in the open air of the country where the habitation is to be erected; or for such indigenous or acclimated plants as it is desired to force or excite into a state of vegetation, or accelerate their maturation at extraordinary seasons. The former description are generally denominated green-houses or botanic stoves, in which the object is to imitate the native climate and soil of the plants cultivated; the latter comprehend forcing-houses and culinary stoves, in which the object is, in the first case, to form an exciting climate and soil, on general principles; and in the second, to imitate particular climates. . . .

- “1595. The introduction and management of light is the most important point to attend to in the construction of hot-houses. . . .

- “1602. The general form and appearance of roofs of hot-houses, was, till very lately, that of a glazed shed or lean-to; differing only in the display of lighter or heavier frame-work or sashes. But Sir George Mackenzie’s paper on this subject, and his plan and elevation of a semi-dome (Hort. Trans. vol. ii. p. 175.), have materially altered the opinion of scientific gardeners. . . .

- “1603. Some forms of hot-houses on the curvilinear principle shall now be submitted, and afterwards some specimens of the forms in common use; for common forms, it is to be observed, are not recommended to be laid aside in cases where ordinary objects are to be attained in the easiest manner; and they are, besides the forms of roofs, the most convenient for pits, frames, and glass tents, as already exemplified in treating of these structures."

- 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (pp. 322–23) [1]

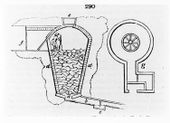

- “1640. Walls of some sort are necessary for almost every description of hot-house, for even those which are formed of glass on all sides are generally placed on a basis of masonry. But as by far the greater number are erected for culinary purposes, they are placed in the kitchen-garden, with the upper part of their roof leaning against a wall, which forms their northern side or boundary, and is commonly called the back wall, and the lower part resting on a low range of supports of iron or masonry, commonly called the front wall. . . .

- “1647. The most general mode of heating hot-houses is by fires and smoke-flues, and on a small scale, this will probably long remain so. Heat is the same material, however produced; and a given quantity of fuel will produce no more heat when burning under a boiler than when burning in a common furnace. Hence, with good air-tight flues, formed of well burnt bricks and tiles accurately cemented with lime-putty, and arranged so as the smoke and hot air may circulate freely, every thing in culture, as far as respects heat, may be perfectly accomplished."

- 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (p. 337) [1]

- “1712. Entrance lodges and gates more properly belong to architecture than gardening. But, as in small places, they are sometimes designed by the garden-architect, or landscape-gardener, a few remarks may be of use. . . . A handsome architectural entrance is but a poor compensation for its want of harmony with the mansion."

- 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (p. 339) [1]

- “1719. Ponds or large basins . . . are reservoirs formed in excavations, either in soils retentive of water, or rendered so by the use of clay. . . . Sometimes these basins are lined with pavement, tiles, or even lead, and the last material is the best, where complete dryness is an object around the margin. . . .[Fig. 11]

- “1722. Collecting and preserving ice, rearing bees, &c. however, unsuitable or discordant it may appear, it has long been the custom to delegate to the care of the gardener. In some cases also he has the care of the dove-house, fish-ponds, aviary, a menagerie of wild beasts, and places for snails, frogs, dormice, rabbits, &c. but we shall only consider the ice-house, apiary, and aviary, as legitimately belonging to gardening, leaving the others to the care of the gamekeeper, or to constitute a particular department in domestic or rural economy."

- 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (p. 340) [1]

- “1725. The form of ice-houses commonly adopted at country-seats, both in Britain and in France, is generally that of an inverted cone, or rather hen’s egg, with the broad end uppermost.”

- 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (pp. 341–42) [1]

- “1733. The care of bees seems more naturally to belong to gardening than the keeping of ice; because their situation is naturally in the garden, and their produce is a vegetable salt. The garden-bee is found in a wild state in most parts of the globe, in swarms or governments; but never in groups of governments so near together as in a bee-house, which is an artificial and unnatural contrivance to save trouble, and injurious to the insect directly as the number placed together. . . . Hence, independently of other considerations, one disadvantage of congregating hives in bee-houses or apiaries. The advantages are, greater facility in protecting from heats, colds, or thieves, and greater facilities of examining their condition and progress. Independently of their honey, bees are considered as useful in gardens, by aiding in the impregnation of flowers. For this purpose, a hive is sometimes placed in a cherry-house, and sometimes in peach-houses; or the position of the hive is in the front or end wall of such houses, so as the body of the hive may be half in the house and half in the wall, with two outlets for the bees, one into the house, and the other into the open air. By this arrangement, the bees can be admitted to the house and open air alternately, and excluded from either at pleasure.

- “1734. The apiary, or bee-house. The simplest form of a bee-house consists of a few shelves in a recess of a wall or other building . . . exposed to the south, and with or without shutters, to exclude the sun in summer, and, in part, the frost in winter. The scientific or experimental bee-house is a detached building of boards, differing from the former in having doors behind, which may be opened at any time during day to inspect the hives. . . . Bee-houses may always be rendered agreeable, and often ornamental objects: they are particularly suitable for flower-gardens; and one may occur in a recess in a wood or copse, accompanied by a picturesque cottage and flower-garden. They enliven a kitchen-garden, and communicate particular impressions of industry and usefulness. . . . [Fig. 6]

- 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (p. 347) [1]

- “1761. The canary or singing-bird aviary used not unfrequently to be formed in the opaque-roofed green-house or conservatory, by enclosing one or both ends with a partition of wire; and furnishing them with dead or living trees, or spray and branches suspended from the roof for the birds to perch on. Such are chiefly used for the canary, bullfinch, linnet, &c.

- “1762. The parrot aviary is generally a building formed on purpose, with a glass roof, front, and ends; with shades and curtains to protect it from the sun and frost, and a flue for winter heating. In these, artificial or dead trees with glazed foliage are fixed in the floor, and sometimes cages hung on them; and at other times the birds allowed to fly loose. . . .

- “1763. The verdant aviary is that in which, in addition to houses for the different sorts of birds, a net or wire curtain is thrown over the tops of trees, and supported by light posts or hollow rods, so as to enclose a few poles, or even acres of ground, and water in various forms. In this the birds in fine weather sing on the trees, the aquatic birds sail on the water, or the gold-pheasants stroll over the lawn, and in severe seasons they betake themselves to their respective houses or cages. Such an enclosed space will of course contain evergreen, as well as deciduous trees, rocks, reeds, aquatics, long grass for larks and partridges, spruce firs for pheasants, furzebushes for linnets, &c. . . .

- “1764. Gallinaceous aviary. At Chiswick, portable netted enclosures, from ten to twenty feet square, are distributed over a part of the lawn, and display a curious collection of domestic fowls. In each enclosure is a small wooden box or house for sheltering the animals during the night, or in severe weather, and for breeding. Each cage or enclosure is contrived to contain one or more trees or shrubs; and water and food are supplied in small basins and appropriate vessels. Curious varieties of aquatic fowls might be placed on floating aviaries on a lake or pond."

- 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (pp. 348, 350–51) [1]

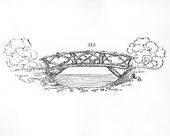

- “1769. Useful decorations are such as while they serve as ornaments, or to heighten the effect of a scene, are also applied to some real use, as in the case of cottages and bridges. They are the class of decorative buildings most general and least liable to objection. . . .

- “1782. The bridge is one of the grandest decorations of garden-scenery, where really useful. None require so little architectural elaboration, because every mind recognises the object in view, and most minds are pleased with the means employed to attain that object in proportion to their simplicity. There are an immense variety of bridges, which may be classed according to the mechanical principles of their structure; the style of architecture, or the materials used. . . .

- “1783. The fallen tree is the original form, and may sometimes be admitted in garden-scenery, with such additions as will render it safe, and somewhat commodious.

- “1784. The foot-plank is the next form, and may or may not be supported in the middle, or at different distances by posts.

- “1785. The Swiss bridge . . . is a rude composition of trees unbarked, and not hewn or polished. . . . [Figs. 9 and 10]

- “1787. A very light and strong bridge may be formed by screwing together thin boards in the form of a segment, or by screwing together a system of triangles of timber. . . .

- “1788. Bridges of common carpentry . . . admit of every variety of form, and either of rustic workmanship or with unpolished materials, or of polished timber alone, or of dressed timber and abutments of masonry.

- “1789. Bridges of masonry . . . may either have raised or flat roads; but in all cases those are the most beautiful (because most consistent with utility) in which the road on the arch rises as little above the level of the road on the shores as possible. . . .

- “1790. Cast-iron bridges are necessarily curved; but that curvature, and the lines which enter into the architecture of their rails, may be varied according to taste or local indications.”

- 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (pp. 352, 354–55) [1]

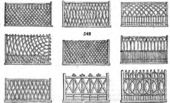

- “1794. The gate is of various forms and materials, according to those of the barrier of which it constitutes a part. In all gates, the essential part of the construction, or those lines which maintain its strength and position, and facilitate its motion, are to be distinguished from such . . . as serve chiefly to render it a barrier, or as decorations. Thus a gate with a raised top or head (fig. 321.) is almost always in bad taste, because at variance with strength; while the contrary form (fig. 320.) is generally in good taste, for the contrary reason. In regard to strength, the nearer the arrangement of rails and bars approaches in effect to one solid lamina, or plate of wood or iron, of the gate’s dimensions, the greater will be the force required to tear or break it in pieces. But this would not be consistent with lightness and economy, and, therefore, the skeleton of a lamina is resorted to, by the employment of slips or rails joined together on mechanical principles; that is, on principles derived from a mechanical analysis of strong bodies. . . . [Fig. 14]

- “1800. Gates, as decorations, may be classed according to the prevailing lines, and the materials used. Horizontal, perpendicular, diagonal, and curved lines, comprehend all gates, whether of iron or of timber, and each of these may be distinguished more or less by ornamental parts, which may either be taken from any of the known styles of architecture, or from heraldry or fancy.

- “1801. The published designs for gates are numerous, especially those for iron gates; for executing which, the improvements made in casting that metal in moulds afford great facilities. By a judicious junction of cast and wrought iron, the ancient mode of enriching gates with flowers and other carved-like ornaments might be happily reintroduced.

- “1802. Gates in garden-scenery, where architectural elegance is not required to support character, simple or rustic structures . . . wickets, turn-stiles, and even moveable or suspended rails, like the German schlagbaum . . . may be introduced according to the character of the scene. . . .[Fig. 15]

- “1804. Walls are unquestionably the grandest fences for parks; and arched portals, the noblest entrances; between these and the hedge or pale, and rustic gate, designs in every degree of gradation, both for lodges, gates, and fences, will be found in the works of Wright, Gandy, Robertson, Aikin, Pocock, and other architects who have published on the rural department of their art. The pattern books of manufacturers of iron gates and hurdles, and of wire workers, may also be advantageously consulted.”

- 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (p. 356) [1]

- “1809. Porches and porticoes . . . are sometimes employed as decorative marks to the entrances of scenes; and sometimes merely as roofs to shelter seats or resting benches.” [Fig. 27]

- "1810. Alcoves . . . are used as winter resting places, as being fully exposed to the sun. . . .[Fig. 1]

- “1811. Arbors are used as summer seats and resting-places: they may be shaded with fruit-trees, as the vine, currant, cherry; climbing ornamental shrubs, as ivy, clematis, &c.; or herbaceous, as everlasting pea, gourd, &c. They are generally formed of timber lattice-work, sometimes of woven rods, or wicker-work, and occasionally of wire.

- “1812. The Italian arbor . . . is generally covered with a dome, often framed of thick iron or copper wire painted, and covered with vines or honeysuckles.

- “1813. The French arbor . . . is characterised by the various lines and surfaces, which enter into the composition of the roof. . . .

- “1815. Grottoes are resting-places in recluse situations, rudely covered externally, and within finished with shells, corals, spars, crystallisations, and other marine and mineral productions, according to fancy. To add to the effect, pieces of looking-glass are inserted in different places and positions.”

- 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (pp. 358-59) [1]

- “1822. Of constructions for displaying water, as an artificial decoration, the principal are cascades, waterfalls, jets, and fountains. . . .

- “1826. The construction of the waterfall, where avowedly artificial, is nothing more than a strong-built wall across the stream, perfectly level at top, and with a strong, smooth, accurately fitted, and well jointed coping. . . . Where a natural waterfall is to be imitated, the upright wall must be built of huge irregular blocks; the horizontal lamina of water broken in the same way by placing fragments of rocks grouped here and there so as to throw the whole into parts; and as nature is never methodical, to form it as if in part a cascade. . . .

- “1827. In imitating a natural cascade in garden-scenery, the horizontal line must here also be perfect, to prevent waste of water in dry seasons, and from this to the base of the lower slope the surface must be paved by irregular blocks, observing to group the prominent fragments, and not distribute them regularly over the surface. . . .

- “1828. The greatest danger in imitating cascades and waterfalls, consisting in attempting too much, a very few blocks, disposed with a painter’s eye, will effect all that can be in good taste in most garden-scenes; and in forming or improving them in natural rivers, there will generally be found indications both as to situation and style, especially if the country be uneven, or stony, or rocky. . . .

- “1829. Jets and other hydraulic devices, though now in less repute than formerly, are not to be rejected in confined artificial scenes, and form an essential decoration where the ancient style of landscape is introduced in any degree of perfection.

- “1830. The first requisite for jets or projected spouts, or threads of water, by atmospheric pressure, is a sufficiently elevated source or reservoir of supply. This being obtained, pipes are to be conducted from it to the situations for the jets. . . .

- “1831. Adjutages are of various sorts. Some are contrived so as to throw up the water in the form of sheaves, fans, showers, to support balls, &c.; others to throw it out horizontally, or in curved lines, according to the taste of the designer; but the most usual form is a simple opening to throw the spout or jet upright. The grandest jet of any is a perpendicular column issuing from a rocky base, on which the water falling, produces a double effect both of sound and visual display. A jet rising from a naked tube in the middle of a basin or canal, and the waters falling on its smooth surface, is unnatural, without being artificially grand.

- “1832. Drooping fountains . . . overflowing vases, shells (as the chama gigas), cisterns, sarcophagi, dripping rocks, and rockworks, are easily formed, requiring only the reservoir to be as high as the orifice whence the dip or descent proceeds. This description of fountains, with a surrounding basin, are peculiarly adapted for the growth of aquatic plants.” [Fig. 12]

- 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (p. 361) [1]

- “1842. Monumental objects, as obelisks, columns, pyramids, may occasionally be introduced with grand effect, both in a picturesque and historical view, of which Blenheim, Stow, Castle Howard, &c., afford fine examples; but their introduction is easily carried to the extreme, and then it defeats itself, as at Stow.”

- 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (p. 375) [1]

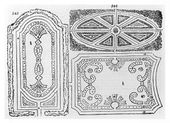

- “1924. Intricate and fanciful figures of parterres are most correctly transferred to ground, as they are copied on paper, by covering the figure to be copied with squares (fig. 363. a) formed by temporary lines intersecting each other at equal distances and right angles, and by tracing on the ground similar squares, but much larger, according to the scale (fig. 363. b). Sometimes the figure is drawn on paper in black, and the squares in red, while the squares on the ground are formed as sawyers mark the intended path of the saw before sawing up a log of timber; that is, by stretching cords rubbed with chalk, which, by being struck on the ground (previously made perfectly smooth), leave white lines. With the plan in one hand and a pointed rod in the other, the design is thus readily traced across these indications. The French and Italians lay out their most curious parterres . . . in this way. [Fig. 7]

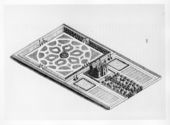

- 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (pp. 451, 455-58, 464-65) [1]

- “2355. To unite the agreeable with the useful is an object common to all the departments of gardening. The kitchen garden, the orchard, the nursery, and the forest, are all intended as scenes of recreation and visual enjoyment, as well as of useful culture; and enjoyment is the avowed object of the flower-garden, shrubbery, and pleasure ground. . . .

- “2382. The situation of the kitchen-garden, considered artificially or relatively to the other parts of a residence, should be as near the mansion and the stable-offices, as is consistent with beauty, convenience, and other arrangements. Nicol observes, ‘In a great place, the kitchen-garden should be so situated as to be convenient, and, at the same time, be concealed from the house. . . .’

- “2383. Sometimes we find the kitchen-garden placed immediately in front of the house, which Nicol ‘considers the most awkward situation of any. . . . Generally speaking, it should be placed in the rear or flank of the house, by which means the lawn may not be broken and rendered unshapely where it is required to be most complete. The necessary traffic with this garden, if placed in front, is always offensive. . . .’

- “2388. Main entrance to the garden. Whatever be the situation of a kitchen-garden, whether in reference to the mansion or the variations of the surface, it is an important object to have the main entrance on the south side, and next to that, on the east or west. The object of this is to produce a favorable first impression on the spectator, by his viewing the highest and best wall (that on the north side) in front; and which is of still greater consequence, all the hot-houses, pits, and frames in that direction. . . .

- “2389. Bird’s-eye view of the garden. When the grounds of a residence are much varied, the general view of the kitchen-garden will unavoidably be looked down on or up to from some of the walks or drives, or from open glades in the lawn or park. Some arrangement will therefore be requisite to place the garden, or so to dispose of plantations that only favorable views can be obtained of its area. To get a bird’s-eye view of it from the north, or from a point in a line with the north wall, will have as bad an effect as the view of its north elevation, in which all its ‘baser parts’ are rendered conspicuous. . . .

- “2396. The extent of the kitchen-garden must be regulated by that of the place, of the family, and of their style of living. In general, it may be observed, that few country-seats have less than an acre, or more than twelve acres in regular cultivation as kitchen-garden, exclusive of the orchard and flower-garden. From one and a half to five acres may be considered as the common quantities enclosed by walls. . . .

- “2401. The kitchen-garden should be sheltered by plantations; but should by no means be shaded, or be crowded by them. If walled round, it should be open and free on all sides, or at least to the south-east and west, that the walls may be clothed with fruit-trees on both sides. . . .

- “2431. In regard to form, almost all the authors above quoted [London, Wise, Evelyn, Hitt, Lawrence] agree in recommending a square . . . or oblong, as the most convenient for a [kitchen] garden; but Abercrombie proposes a long octagon, in common language, an oblong with the angles cut off. . . .

- “2436. Walls are built round a garden chiefly for the production of fruits. A kitchen-garden, Nicol observes, considered merely as such, may be as completely fenced and sheltered by hedges as by walls, as indeed they were in former times, and examples of that mode of fencing are still to be met with. But in order to obtain the finer fruits, it becomes necessary to build walls, or to erect pales and railings."

- 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (p. 482) [1]

- “2527. An orchard, or separate plantation of the hardier fruit-trees is a common appendage to the kitchen-garden, where that department is small, or does not contain an adequate number of fruit-trees to supply the contemplated demand of the

family. Sometimes this scene adjoins the garden, and forms a part of the slip; at other times it forms a detached, and, perhaps, distant enclosure, and not unfrequently, in countries where the soil is propitious to fruit-trees, they are distributed in the lawn, or in a scene, or field kept in pasture. Sometimes the same object is effected by mixing fruit-trees in the plantations near the garden and house.”

- 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (pp. 789-802) [1]

- “6075. Floriculture. . . . The culture of flowers was long carried on with that of culinary vegetables, in the borders of the kitchen-garden, or in parterres or groups of beds, which commonly connected the culinary compartments with the house. In places of moderate extent, this mixed style is still continued; but in residences which aim at any degree of distinction, the space within the walled garden is confined to the production of objects of domestic utility, while the culture of plants of ornament is displayed in the flower-garden and the shrubbery. These, under the general term of pleasure-ground, encircle the house in small seats, and on a larger scale embrace it in one or more sides; the remaining part being under the character of park-scenery. . . .

- “6076. The situation of the flower-garden, as of every department of floriculture, should be near the house, for ready access at all times, and especially during winter and spring, when the beauties of this scene are felt with peculiar force. . . .

- “6079. To place the flower-garden south-east or south-west of the house, and between it and the kitchen-garden, is in general a desirable circumstance. . . .

- “6080. In exposure and aspect, the flower-garden should be laid out as much as possible on the same principles as the kitchen-garden. . . .

- “6081. The extent of the flower-garden depends jointly on the general scale of the residence, and the particular taste of the owner. If any proportion may be mentioned, perhaps, a fifth part of the contents of the kitchen-garden will come near the general average; but there is no impropriety in having a large flower-garden to a small kitchen-garden. . . . As moderation, however, is generally found best in the end, we concur with the author of the Florist’s Manual, when she states, that ‘. . . If the form of ground, where a parterre is to be situated, is sloping, the size should be larger than when a flat surface, and the borders of various shapes, and on a bolder scale, and intermingled with grass; but such a flower-garden partakes more of the nature of pleasure-ground than of the common parterre, and will admit of a judicious introduction of flowering shrubs.’ . . .

- “6082. Shelter is equally requisite for the flower as for the kitchen garden, and, where naturally wanting, is to be produced by the same means, viz. planting. . . . Sometimes an evergreen hedge will produce all the shelter requisite, as in small gardens composed of earth and gravel only . . . but where the scene is large . . . and composed of dug compartments (a), placed on lawn (b) the whole may be surrounded by an irregular border (c) of flowers, shrubbery, and trees. . . . [Fig. 5]

- “6086. Water. This material, in some form or other, is as essential to the flower as to the kitchen-garden. Besides the use of the element in common culture, a pond or basin affords an opportunity of growing some of the more showy aquatics, while jets, dropping-fountains, and other forms of displaying water, serve to decorate and give interest to the scene. . . .

- “6087. The form of a small garden . . . will be found most pleasing when some regular figure is adopted, as a circle, oval, octagon, crescent, &c.: but where the extent is so great as not readily to be caught by a single glance of the eye, an irregular shape is generally more convenient, and it may be thrown into agreeable figures, or component scenes, by the introduction of shrubs so as to subdivide the space. . . .

- “6090. Boundary fence, or screen. Parterres on a small scale may be enclosed by an evergreen hedge of holly, box, laurel, privet, juniper, laurustinus, or Irish whin . . . but irregular figures, especially if of some extent, can only be surrounded by a shrubbery, such as we have already hinted at (6082.) as forming a proper shelter for flower-gardens. . . .

- “6093. Laying out the area. . . . In laying out the area of the kitchen-garden, its destination being utility, affords in all cases a safe and fixed guide; but the flower-garden is a matter of fancy and taste, and where these are wavering and unsettled, the work will be found to go on at random. As flower-gardens are objects of pleasure, that principle which must serve as a guide in laying them out, must be taste. Now, in flower-gardens, as in other objects, there are different kinds of tastes; these embodied are called styles or characters; and the great art of the designer is, having fixed on a style, to follow it out unmixed with other styles, or with any deviation which would interfere with the kind of taste or impression which that style is calculated to produce. Style, therefore, is the leading principle in laying out flower-gardens, as utility is in laying out the culinary-garden. As subjects of fancy and taste, the styles of flower-gardens are various. The modern style is a collection of irregular groups and masses, placed about the house as a medium, uniting it with the open lawn. The ancient geometric style, in place of irregular groups, employed symmetrical forms; in France, adding statues and fountains; in Holland, cut trees and grassy slopes; and in Italy, stone walls, walled terraces, and flights of steps. In some situations, these characteristics of parterres may with propriety be added to, or used instead of the modern sort, especially in flat situations, such as are enclosed by high walls in towns, or where the principal building or object is in a style of architecture which will not render these appendages incongruous. There are other characters of gardens, such as Chinese, which are not widely different from the modern; the Indian, which consists chiefly of walks under shade, in squares of grass, &c.; the Turkish, which abounds in shady retreats, boudoirs of roses and aromatic herbs; and the Spanish, which is distinguished by trellis-work and fountains: but these gardens are not generally adapted to this climate, though from contemplating and selecting what is beautiful or suitable in each, a style of decoration for the immediate vicinity of mansions might be composed, greatly preferable to any thing now in use. . . .

- “6097. The materials which form the surface of flower-gardens . . . are gravel (a), turf (b), and dug borders, (c), patches (d), or compartments (e), and water (f); but a variety of other objects and materials may be introduced as receptacles for plants, or on the surfaces of walks; as grotesque roots, rocks, flints, spar, shells, scoriae in conglomerated lumps, sand and gravel of different colors; besides works of art introduced as decorations, or tonsile performances, when the old French style . . . is imitated.” [Fig. 8]

- “6099. The green-house or conservatory is generally placed in the flower-garden, provided these structures are not appended to the house. . . .

- “6106. In extensive and irregular parterres, one gravel-walk, accompanied by broad margins of turf, to serve as walks by such as prefer that material, should be so contrived as to form a tour for the display of the whole garden. There should also be other secondary interesting walks of the same width, of gravel and smaller walks for displaying particular details. The main walk, however, ought to be easily distinguishable from the others by its broad margins of fine turf. In general the gravel is

of uniform breadth throughout the whole length of the walk; but in that sort of French parterres which they call parterres of embroidery . . . the breadth of the gravelled part (a) varies like that of the turf. Such figures, when correctly executed, carefully planted, judiciously intermixed with basket-work, shells, party-colored gravels, &c. and kept in perfect order, are highly ornamental; but very few gardeners enter into the spirit of this department of their art. The French and Dutch have long greatly excelled us in the formation of small gardens, and the display of flowers; and whoever wishes to succeed in this department ought to visit Amsterdam, Antwerp, Brussels, and Paris; and consult the old French works of Mallet, Boyceau, Le Blond, &c. [Fig. 9]

- “6107. Edgings. In parterres where turf is not used as a ground or basis out of which to cut the beds and walks, the gravel of the latter is disparted from the dug ground of the former by edgings or rows of low-growing plants, as in the kitchen-garden. Various plants have been used for this purpose; but, as Neill observes, the best for extensive use is the dwarfish Dutch box, kept low and free from blanks. Abercrombie says, ‘Thrift is the neatest small evergreen next to box. In other parts, the daisy, pink, London-pride, primrose, violet, and periwinkle, may be employed as edgings. The strawberry, with the runners cut in close during summer, will also have a good effect; the wood-strawberry is suitable under the spreading shade of trees. Lastly, the limits between the gravel-walks and the dug-work may sometimes be marked by running verges of grass kept close and neat. Whatever edgings are employed, they should be formed previous to laying the gravel.’

- “6108. Basket-edgings. Small groups near the eye, and whether on grass or gravel, may be very neatly enclosed by a worked fence of basket-willows from six inches to a foot high. These wicker-work frames may be used with or without verdant edgings; they give a finished and enriched appearance to highly polished scenery; enhance the value of what is within, and help to keep off small dogs, children, &c. . . .

- “6110. The manner of planting the herbaceous plants and shrubs in a flower-garden depends jointly on the style and extent of the scene. With a view to planting, they may be divided into three classes, which classes are independently altogether of the style in which they are laid out. The first class is the general or mingled flower-garden, in which is displayed a mixture of flowers with or without flowering-shrubs according to its size. The object in this class is to mix the plants, as that every part of the garden may present a gay assemblage of flowers of different colors during the whole season. The second class is the select flower-garden, in which the object is limited to the cultivation of particular kinds of plants; as, florists’ flowers, American plants, annuals, bulbs, &c. Sometimes two or more classes are included in one garden, as bulbs and annuals; but, in general, the best effect is produced by limiting the object to one class only. The third class is the changeable flower garden, in which all the plants are kept in pots, and reared in a flower-nursery or reserve-ground. As soon as they begin to flower, they are plunged in the borders of the flower-garden, and, whenever they show symptoms of decay, removed, to be replaced by others from the same source. This is obviously the most complete mode of any for a display of flowers, as the beauties of both the general and particular gardens may be combined without presenting blanks, or losing the fine effect of assemblages of varieties of the same species; as of hyacinth, pink, dahlia, chrysanthemum, &c. The fourth class is the botanic flower-garden, in which the plants are arranged with reference to botanical study, or at least not in any way that has for its main object a rich display of blossoms. . . .

- “6126. The botanic flower-garden being intended to display something of the extent and variety of the vegetable kingdom, as well as its resemblances and differences, should obviously be arranged according to some system or method of study. In modern times, the choice is almost limited to the artificial system of Linnaeus, and the natural method of Jussieu, though Adanson has given above fifty-six different methods by which plants may be arranged. . . . Whatever method is adopted, the plants may either be placed in regular rows, or each order may be grouped apart, and surrounded by turf or gravel. For a private botanic garden, the mode of grouping on turf is much the most elegant. . . .A gravel walk may be so contrived as to form a tour of all the groups [of species] (fig. 553.), displaying them on both sides; in the centre, or in any fitting part of the scene, the botanic hot-houses may be placed; and the whole might be surrounded with a sloping phalanx of evergreen plants, shrubs, and trees. . . . It is hardly necessary to observe that the above modes, or others that we have mentioned of planting a flower-garden are alike applicable to every form or style of laying out the garden or parterre. . . . [Fig. 6]

- “6127. Decorations. Even the apiary and aviary, or, at least, here and there a beehive, or a cage suspended from a tree, will form very appropriate ornaments.”

- 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (p. 809) [1]

- “6157. . . . Light bowers formed of lattice-work, and covered with climbers, are in general most suitable to parterres; plain covered seats suit the general walks of the shrubbery.”

- 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (pp. 811–14) [1]

- “6161. The hot-houses of floriculture are the frame, glass case, green-house, orangery, conservatory, dry-stove, the bark or moist stove, in the flower-garden, or pleasure-ground; and the pit and hot-bed in the reserve-garden. In the construction of all of these the great object is, or ought to be, the admission of light and the power of applying artificial heat with the least labor and expense. . . .

- “6164. The green-house may be designed in any form, and placed in almost any situation as far as respects aspect. Even a house looking due north, if glazed on three sides of the roof, will preserve plants in a healthy vigorous state. A detached green-house, even in the old style, may be rendered an agreeable object in a pleasure-ground . . . but the curvilinear principle applied to this class of structures, admits of every combination of form, and without militating against the admission of light and air. Though we are decidedly of opinion, however, that as iron roofs on the curvilinear principle become known, the clumsy shed-like wooden or mixed roofs now in use will be erected only in nursery and market-gardens. . . .

- “6165. The most suitable description of greenhouse or conservatory for the flower-garden is that with span roof . . . because such a house has no visible ‘hinder parts,’ back sheds, stock-holes, or other points of ugliness, with which it is difficult to avoid associating all the shed, or lean-to forms of glazed buildings with back walls. . . .

- “6166. In the interior of the green-house the principle object demanding attention is the stage, or platform for the plants. . . .

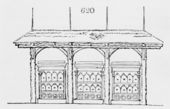

- “6171. The orangery is the green-house of the last century, the object of which was to preserve large plants of exotic evergreens during winter, such as the orange tribe, myrtles, sweet bays, pomegranates, and a few others. . . . The orangery was generally placed near to or adjoining the house, and its elevation corresponded in architectural design with that of the mansion. From this last circumstance has arisen a prejudice highly unfavorable to the culture of ornamental exotics, namely, that every plant-habitation attached to a mansion should be an architectural object, and consist of windows between stone piers or columns, with a regular cornice and entablature. By this mode of design, these buildings are rendered so gloomy as never to present a vigorous vegetation, and vivid glowing colors within; and as they are thus unfit for the purpose for which they are intended, it does not appear to us, as we have already observed at length (1590.), that they can possibly be in good taste. Perhaps the only way of reconciling the adoption of such apartments with good sense, is to consider them as lounges or promenade scenes for recreation in unfavorable weather, or for use during fêtes, in either of which cases they may be decorated with a few scattered tubs of orange-trees, camellias, or other evergreen coriaceous-leaved plants from a proper green-house, and which will not be much injured by a temporary residence in such places, which, as Nicol has observed, ‘often look more like tombs or places of worship, than compartments for the reception of plants; and, we may add that the more modern sort look like a combination of shop-fronts, of which that at Claremont is a notable example.’ Sometimes structures of this sort are erected to conceal some local deformity, of which, as an instance, we may refer to that . . . erected by Todd, for J. Elliot, Esq., at Pimlico. ‘This building was constructed for the purpose of preventing the prospect of some offices from the dwelling-house. The architectural ornaments, and the roof, not being of glass, are points in the construction not generally to be recommended; but, as it was built for the purpose above mentioned, the objections were overruled. There are three circular stages to this house, which are made to take out at pleasure. The ceiling forms part of a circle, and the floor is paved with Yorkshire stone. It is fifty feet long, and thirteen feet six inches wide, and heated by one fire, the flue from which makes the circuit of the house under the floor.’ (Plans of Green-Houses, &c. p. 10)”. . . .[Fig. 9]

- “6174. The conservatory is a term generally applied by gardeners to plant-houses, in which the plants are grown in a bed or border without the use of pots. They are sometimes placed in the pleasure-ground along with the other hot-houses; but more frequently attached to the mansion. The principles of their construction is in all respects the same as for the green-house, with the single difference of a pit or bed of earth being substituted for the stage, and a narrow border instead of surrounding flues. The power of admitting abundance of air, both by the sides and roof, is highly requisite both for the green-house and conservatory; but for the latter, it is desirable, in almost every case, that the roof, and even the glazed sides, should be removable in summer.” [Fig. 11]

- 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (pp. 942–43) [1]

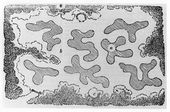

- “6811. In regard to extent, the least is a group (fig. 628. e and d), which must consist at least of two plants; larger, it is called a thicket (b c); round and compact, it is called a clump (a); still larger, a mass; and all above a mass is denominated a wood or forest, and characterised by comparative degrees of largeness. The term wood may be applied to a large assemblage of trees, either natural or artificial; forest, exclusively to the most extensive or natural assemblages. . . .

- “6813. With respect to the disposition of the trees within the plantation, they may be placed regularly in rows, squares, parallelograms, or quincunx; irregularly in the manner of groups; without undergrowths, as in groves (fig. 629. a, b); with undergrowths, as in woods (c); all undergrowths, as in copse-woods (d). Or they may form avenues (fig. 630. a); double avenues (b); avenues intersecting in the manner of a Greek cross (c); of a martyr’s cross (d); of a star (e) or of a cross patée, or duck’s foot (patée d’oye) (f)."

- 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (pp. 950, 952) [1]

- “6853. The situations [of plantations] to be planted, with a view to effect, necessarily depends on the kind of effect intended; these may reduced to three—to give beauty and variety to general scenery, as in forming plantations here and there throughout a demesne; to give form and character to a country-residence, as in planting a park and pleasure-grounds; and to create a particular and independent beauty or effect, as in planting an extensive area or wood, unconnected with any other object, and disposing of the interior in avenues, glades, and other forms. . . .

- “6855. The outline of plantations, made with a view to the composition of a country-residence, is guided by the same general principles; whether the trees are to be disposed in regular forms, avowedly artificial; or in irregular forms, in imitation of nature. . . . The first thing is, in both modes, to compose a principal mass, from which the rest may appear to proceed; or be, or seem to be, connected.”

- 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (p. 965) [1]

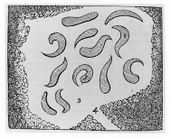

- “6923. Ornamental plantations are no less frequently neglected than such as are considered chiefly useful. Clumps, belts, and screens which have become thin, because they have not been thinned, are almost every where to be met with. ‘In those neglected plantations,’ says Lord Meadowbank, ‘where daylight may be seen for miles, through, naked stems, chilled and contracted by the cold, the mischief might, perhaps, be partially remedied, by planting young trees round the extremities, which, having room to spread luxuriantly, would exclude the winds, and the internal spaces might be thickened up with oak, silver firs, beeches, and such other trees as thrive with a small portion of light. When once the wind is excluded, the weakest of the old trees might be taken out, and the others left to profit by the shelter and space that is afforded.’ (Life of Lord Kaimes, by Tytler.) One of the most hopeless cases of improvement in this department is that of an old clump of Scotch pines . . . from which scarcely any trees can be taken without risking the failure of the remainder. The only way is to add to it, either by some scattered groups in one direction, or in various directions. Where a clump consists of a hard wood, either entirely or in part, it may sometimes, if effect permits, be reduced to a group, by gradually reducing the number of the trees. The group left should be composed of two or three trees of at least two species, different in bulk, and some what in habit, in order that the combined mass may not have the formality of the clump.” [Fig. 4]

- 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (pp. 973-74) [1]

- “6973. Nurseries for rearing trees are commonly left to commercial gardeners, as the plantations of few private landowners are so extensive, or continued through a sufficient number of years to render it worth their while to originate and nurse up their own tree and hedge plants. Exceptions, however, occur in the case of remote situations, and where there are tracts so extensive as to require many years in planting. . . .

- “6982. The principal objects of culture in a private tree-nursery are the hardy trees and shrubs of the country, which produce seeds; and the great object of the private nursery-gardener must be to collect or procure these seeds, prepare them for sowing, sow them in their proper seasons, and transplant and nurse them till fit for final planting."

- 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (pp. 994-96) [1]

- “7156. In landscape gardening, the art of the gardener is directed to different objects, and some of them of a higher kind than any belonging to gardening as an art of culture. In the three branches [of gardening] hitherto considered, art is chiefly employed in the cultivation of plants, with a view of obtaining their products; but in the branch now under consideration, art is exercised in disposing of ground, buildings, and water, as well as the vegetating materials which enter into the composition of verdant landscape. This is, in a strict sense, what is called landscape-gardening, or the art of creating or improving landscapes; but as landscapes are seldom required to be created for their own sakes, landscape-gardening, as actually practised, may be defined, ‘the art of arranging the different parts which compose the external scenery of a country-residence, so as to produce the different beauties and conveniences of which that scene of domestic life is susceptible.’ . . .

- “7161. With respect to the modern style, considered as including what belongs to the conveniences of a country-residence, as well as the art of creating landscapes, Pope has included the principles under, 1st, The study and display of natural beauties; 2d, The concealment of defects; and 3d, Never to lose sight of common sense. Wheatley concurs in these principles, stating the business of a gardener to be ‘to select and to apply whatever is great, elegant, or characteristic’ in the scenery of nature or art; ‘to discover and to show all the advantages of the place upon which he is employed; to supply its defects, to correct its faults, and to improve its beauties.’ Repton, whose observations on landscape-gardening bear on the title-page, to be ‘written with a view to establish fixed principles in these arts,’ enumerates congruity, utility, order, symmetry, scale, proportion, and appropriation, as principles, ‘if,’ as he observes, in one place, ‘there are any principles.’ Mason places the secret of the art in the ‘nice distinction

between contrast and incongruity;’ Mason, the poet, invokes ‘simplicity,’ probably intending that this beauty should distinguish the English from the Chinese style: simplicity is also the ruling principle of Lord Kames; Girardin includes every beauty under ‘truth and nature,’ and every rule ‘under the unity of the whole, and the connection of the parts;’ and Shenstone states, ‘landscape or picturesque gardening’ to ‘consist in pleasing the imagination,’ by scenes of grandeur, beauty, and variety. Convenience merely has no share there, any farther than as it pleases the imagination. Congruity and the principles of painting are those of Price and Knight; and nature, utility, and taste, those of Marshall. From these different theories [of landscape gardening], as well as from the general objects or end of gardening, there appear to be two principles which enter into its composition; those which regard it as a mixed art, or an art of design, and which are called the principles of relative beauty; and those which regard it as an imitative art, and are called the principles of natural or universal beauty. The ancient or geometric gardening is guided wholly by the former principles; landscape-gardening, as an imitative art, wholly by the latter; but as the art of forming a country-residence, its arrangements are influenced by both principles. In conformity with these ideas, and with our plan of treating both styles, we shall first consider its principles as an inventive or mixed, and secondly as an imitative art."

- 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (p. 1000) [1]

- “7180. As an illustration of the theory of landscape-gardening, which we have adopted, we subjoin a slight analysis of the principles of a composition, expressive of picturesque and natural beauty. For this purpose, it is a matter of indifference, as far as respects picturesque beauty, whether we choose a real or painted landscape; but, as we mean also to investigate its poetic or general beauty, we shall prefer a reality. We choose then a perfect flat, varied by wood, say elms, with a piece of water, and a high wall, forming the angle of a ruined building; it is animated by cows and sheep; its expression is that of melancholy grandeur; and, independently of this beauty, it is picturesque in expression; that is, if painted it would form a tolerable picture.”

- 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (p. 1002) [1]

- “7196. . . . If a deformed space has been restored to natural beauty, we are delighted with the effect, whilst we recollect the difference between the present and the former surface; but when this is forgotten, though the beauty remains, the credit for having produced it is lost. In this respect, the operations on ground under the ancient style, have a great and striking advantage; for an absolute perfection is to be attained in the formation of geometrical forms, and the beauty created is so entirely artificial . . . as never to admit a doubt of its origin."

- 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (pp. 1005–6) [1]

- “7205. In planting in the geometric style, the first consideration is the nature of the whole or general design; and here, as in the ground, geometric forms will still prevail, and while the masses reflect forms from the house, or represent squares, triangles, or trapeziums, the more minute parts, characterised by lines rather than forms, such as avenues, rows, clumps, and stars, &c. are contained in parallelograms, squares, or circles. In regard to the parts, masses and avenues should extend from the house in all directions, so far as to diffuse around the character of design; and as much farther in particular directions as the nature of the surface admits of, the distant beauties suggest, and the character of the mansion requires. In disposing these masses, whether on a flat or irregular surface, regard will be had to leave uncovered such a quantity of lawn or turf as shall, at all events, admit a free circulation of air, give breadth of light, and display the form of the large masses of wood. Uniformity and variety as a whole, and use as well as beauty in the parts, must be kept constantly in view. Avenues, alleys, and vistas, should serve as much as possible as roads, walks, lines of fences, or screens of shelter or shade; but where this is not the case, they should point to some distant beauties, or near artificial objects, to be seen at or beyond their termination. The outer extremities of artificial plantations may either join natural woods, other artificial scenes, cultivated lands, or barren heaths or commons."

- 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (pp. 1010–11) [1]

- “7217. To imitate lakes, rivers, or rills, and their accompaniments, is the object of landscape-gardening; and of each of these natural characters we shall remark the leading circumstances in the originals and the imitations. . . .

- “7219. Ponds in different levels, seen in the same view, are very objectionable on this principle. The little beauty they display as spots, ill compensates for the want of propriety; and the leading idea which they suggest, is a question between their present situation and their non-existence. The choice, therefore, as to the situation of water, must ever depend more on natural circumstances than proximity to the mansion. Is then all water to be excluded that is not in the lower grounds? We have no hesitation in answering this question in the affirmative, so far as respects the principal views, and when a lower level than that in which the water is proposed to be placed is seen in the same view. But in respect to recluse scenes, which Addison compares to episodes to the general design, we would admit, and even copy the ponds on the sides or even tops of hills, which may be designated accidental beauties of nature. In confined spots they are often a very great ornament . . . as a proof of which, we have only to observe some of the suburban villas round the metropolis, where a small piece of water often comes in between the house and the public road with the happiest effect.”

- “7220. A beautiful lake, or part of a circuitous body of water, considered as a whole, will be found to exhibit a form, characterised by breadth rather than length; by that degree of regularity in its outline as a whole, which confers that, which, in common language, is called shape; and by that irregularity in the parts of this outline, which produces variety and intricacy. Supposing the situation to be fixed on for the imitation of a lake . . . the artist is to consider the broadest and most circuitous hollow as his principal mass or breadth of water, and which he will extend or diminish according to the extent of aquatic views the place may require. From this he may continue a chain of connected masses of water, or lakes of different magnitudes and shapes, in part suggested by the character of the ground, in part by the facilities of planting near them, and in part by his own views of propriety and beauty. The outline of the plan of the lake is to be varied by the contrasted position of bays, inlets, and smaller indentations, on the same principles which we suggested for varying a mass of wood.”

- 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (p. 1012) [1]

- “7225. A waterfall, or cascade, is an obvious improvement where a running stream passes through a demesne . . . and is to be formed by first constructing a bank of masonry, presenting an inclined plane (a) to the currents, and rendering it impervious to water by puddling (1720.) or the use of proper cements, and next varying the ridge (b) and under side (c), with fragments of rock, so chosen and placed, as not to present a character foreign to what nature may be supposed to have produced there. The adjoining ground generally requires to be raised at such scenes, but may generally be harmonised by plantation. [Fig. 7]

- “7226. Where running water is conducted in forms belonging to the geometric style of gardening, waterfalls and cascades are constructed in the form of crescents, flights of steps, or wavy slopes.”

- 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (pp. 1020-21) [1]

- “7256. Terrace and conservatory. We observed, when treating of ground, and under the ancient style, that the design of the terrace must be jointly influenced by the magnitude and style of the house, the views from its windows, (that is, from the eye of a person seated in the middle of the principal rooms,) and the views of the house from a distance. In almost every case, more or less of architectural form will enter into these compositions. . . .

- “7258. Narrow terraces. . . . Where the breadth is more than is requisite for walks, the borders may be kept in turf with groups or marginal strips of flowers and low shrubs. In some cases, the terrace-walls may be so extended as to enclose ground sufficient for a level plot to be used as a bowling-green or a flower-garden. These are generally connected with one of the living-rooms or the conservatory, and to the latter is frequently joined an aviary and the entire range of botanic stoves. Or, the aviary may be made an elegant detached building, so placed as to group with the house and other surrounding objects. An elegant structure of this sort . . . was designed by Repton for the grounds of the Pavilion at Brighton. . . .[Fig. 7]

- “7259. The flower-garden should join both the conservatory and terrace; and, where the botanic stoves do not join the conservatory and the house, they, and also the aviary and other appropriate buildings and decorations, should be placed here.

- “7260. The kitchen-garden should be placed near to, and connected with the flower-garden, with concealed entrances and roads leading to the domestic offices for culinary purposes, and to the stables and farm-buildings for manure. . . .

- “7262. The lawn, or that breadth of mown turf formed in front of, or extending in different directions from, the garden-front of the house, is, in the geometric style, varied by architectural forms, levels, and slopes; and in the modern by a picturesque or painter-like disposition of groups, placed so as to connect with the leading masses, and throw the lawn into an agreeable shape or shapes. In very small villas the lawn may embrace the garden or principal front of the house, without the intervention of terrace-scenery, and may be separated from the park, or park-like field, by a light wire fence; but in more extensive scenes it should embrace a terrace, or some avowedly artificial architectural basis to the mansion, and a sunk wall, as a distant separation, will be more dignified and permanent than any iron fence. The park may come close up to the terrace-garden, especially in a flat situation, or where the breadth of the terrace is considerable. . . .

- “7265. The park is a space devoted to the growth of timber, pasturage for deer, cattle, and sheep, and for adding grandeur and dignity to the mansion. On its extent and beauty, and on the magnitude and architectural design of the house, chiefly depend the reputation and character of the residence. In the geometric style, the more distant or concealed parts were subdivided into fields, surrounded by broad stripes or double rows, enclosed in walls or hedges, and the nearer parts were chiefly covered with wood, enclosing regular surfaces of pasturage. In the modern style, the scenery of a park is intended to resemble that of a scattered forest, the more polished glades and regular shapes of lawn being near the house, and the rougher parts towards the extremities. . . .

- “7267. The riding, or drive, is a road indicated rather than formed, which passes through the most interesting and distant parts of a residence not seen in detail from the walks, and as far into the adjoining lands of wildness or cultivation, as the property of the owner extends. It is also frequently conducted as much farther as the disposition of adjoining proprietors permits, or the general face of the country renders desirable.”

- 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (p. 1023) [1]

- “7280. The ferme ornée differs from a common farm in having a better dwelling-house, neater approach, and one partly or entirely distinct from that which leads to the offices. It also differs as to the hedges, which are allowed to grow wild and irregular . .and are bordered on each side by a broad green drive, and sometimes by a gravel-walk and shrubs. It differs from a villa farm in having no park.” [Fig. 2]

- 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (p. 1028) [1]

“7313. Public parks, or equestrian promenades, are valuable appendages to large cities. Extent and a free air are the principle requisites, and the roads should be arranged so as to produce few intersections; but at the same time so as carriages may make either the tour of the whole scene, or adopt a shorter tour at pleasure. In the course of long roads, there ought to be occasional bays or side expansions to admit of carriages separating from the course, halting or turning. Where such promenades are very extensive, they are furnished with places of accommodation and refreshment, both for men and horses; this is a valued part of their arrangement for occasional visitors from a distance, or in hired vehicles.”

- 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (p. 1030) [1]

- “7323. Botanic gardens. The primary object of botanic gardens is to exhibit a collection of plants for the improvement of botanical science; a secondary object to exhibit living specimens of such plants as are useful in medicine, agriculture, and other arts; and a third is, or ought to be, the acclimating of foreign plants, and their dissemination over the country. In choosing a situation for a botanic garden, the leading object must be proximity to the town, city, or university to which it is to belong; and the next, if attainable, a variety of surface and soil, to aid the necessary formation of composts and aspects for different plants. . . . As the leading object or feature in the view of a botanic garden is the range of hot-houses; and as these must always face the south, it is generally desirable that ground on the north side of the principal public street or road by which it is to be approached, should be preferred to ground on the south side.

- “7325. The form of a botanic garden is a matter of very little consequence: where the extent is small, a square or parallelogram may undoubtedly be made to contain most plants; but where it exceeds four or five acres, any form will answer; and, indeed, if there is a sufficient quantity of ground, the more irregular the form, so much the more variety will there be in the circumferential walks of the garden.”

- 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (pp. 1033-34) [1]

- “7338. The dwellinghouse of the master. . . .