Project Introduction

The digital resource History of Early American Landscape Design (HEALD) is an illustrated historical inquiry into landscape and garden design in America from the 17th to the mid-19th centuries that explores the relationships between textual and visual representations of landscape design. With an extensive corpus of original texts and images, it offers a discussion of select terms, places, and people from this period, modeling an approach to interpreting early American gardens and landscapes as they were both imagined and actually built. Drawing upon a wealth of newly compiled documentation, HEALD brings together interpretive essays, textual citations, and images in an effort to reveal landscape history as integral to the study of American cultural history.

This digital database results from a research project of the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts under the direction of Therese O’Malley, and is based on the book Keywords in American Landscape Design (Yale University Press, 2010). The Keywords title was inspired by Raymond Williams’s book Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society, because both works share a cultural rather than etymological approach to language.[1] The HEALD database resource, like its predecessor, Keywords, establishes an historically documented vocabulary for describing landscape and garden features that arises out of contemporaneous primary materials.

In its expanded digital edition, HEALD incorporates many more features than the original Keywords project, including, most importantly, pages devoted to one hundred significant Places and one hundred notable People; nearly 2,000 images, each with detailed object pages; enriched archival materials; and a bibliographic feature that links directly to thousands of digitized sources. For ease of navigation, the website uses an open-source MediaWiki format because of its familiarity for web users worldwide, and also because of its utilization of a popular, scripting language that is especially suited to web development.

The corpus of essays and archival materials—both textual and visual—can be examined comparatively, enabling users to see designed landscapes in dynamic contexts and through materials that are in many cases rare and difficult to access. Due to the flexible nature of the digital format, scholars will be able to consider gardens and landscape as part of a larger set of processes—aesthetic, social, economic, and political—rather than as static locations. The website’s flexibility and ease of navigation will permit the user to direct how the information is compiled, organized, and viewed.

Project Methodology

From its inception, the major effort of this project was gathering evidence of gardens as they were represented textually and visually in a variety of documents and objects. These two bodies of evidence are intimately related, and it is at their intersection that landscape history becomes most powerful as an avenue of inquiry into American cultural history. Each source demands an understanding of the particular conventions, contexts, and issues surrounding it.

The primary task was selecting terms found in primary historical sources. In developing the project, the focus was not on creating a comprehensive list encompassing every term referenced in writings on landscape design, but rather on identifying the significant elements as indicated by the frequency of use, the richness of the visual record associated with them, the contemporary importance of the concepts they conveyed, and their position in the history of landscape design. We began with a list of sources, rather than a list of terms, letting the voices in the works determine the words selected. The initial list of selected terms was quite long, but fairly quickly the repetition, detail, and significance of a smaller number of those terms became evident. The final one hundred terms are truly “keywords” in the history of American landscape design.[2] They represent a spectrum of landscape features along a number of interpretive axes. These include both “high art” and “vernacular” features, stylistic and architectural terms, the common and the rare, features valued for their iconographical associations and those whose importance lay in their essential functions in the landscape. The corpus comprises terms of archaeological interest (landscape features that tend to have below-ground impact and can be recovered archaeologically) and terms of art historical interest (those of relevance to the interpretation of visual representations of the American landscape).

The geographic boundaries of this project focus on sites in what is today the continental United States, with the vast majority of citations and images coming from the English colonies of the Eastern Seaboard and the states that they became in the new Republic. It does not include sites in Canada, the Caribbean, or Latin America.[3] The temporal parameters range from the 17th century to the year 1852, which marks the death of landscape designer and theorist Andrew Jackson Downing. This date range encompasses the significant period of development of landscape-design vocabulary when books, such as Downing’s Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, and periodicals, such as his Horticulturist, ushered in a new era for the transmission of landscape theory and the standardization of design vocabulary.

Due in part to the geographic and temporal range of the project, textual evidence is limited to English-language sources. Terms from other languages are included when they appear to have been used commonly in American English sources and when no American-English equivalent appears to have been used (for example, parterre and veranda). If a foreign-language term is used interchangeably with an American-English equivalent or in anglicized spelling, it is included within the English term record (for example, allée under alley and jet d’eau under jet). Citations from English-language translations of treatises are included, provided they were made prior to 1852 and known in America. Translated accounts have been included under the date of the translation, rather than the date of the original account, assuming that they reflect the vocabulary of the translator, a significant factor in the understanding of the passage.

References were compiled from published and unpublished primary sources such as diaries, correspondence, travelers’ accounts, treatises, newspapers, periodicals, drawings, insurance documents, maps, and almanacs. The secondary literature on American landscape design also provided information on primary sources, as well as discussions of the issues and themes of landscape design history.[4] Of particular value were publications and other materials produced at historic sites. These included not only annual reports, newsletters, archaeological site reports, research reports, and brochures, but also a growing body of cultural landscape reports and inventories, which were helpful in locating otherwise unpublished images and descriptions and for summarizing archaeological investigations. Research in archives yielded some citations, but the vast majority of those presented were compiled from published sources. They also include generous contributions by scholars of their original research.[5]

The data gathered do not represent a statistically significant sample of designed landscapes, but rather they reflect the history of research on American landscapes. Coverage is broader for the Chesapeake and mid-Atlantic regions, because of the concentration of sites and the preservation of records in these areas, and, as a result of these fortuitous circumstances, the wealth of garden history research pertaining to these regions. As a result of the 1852 end date for inclusion, the coverage for sites west of the Appalachians is sparse because landscape design in that area was generally not well developed until the second half of the 19th century. Furthermore, the restriction to English-language sources limits the information on garden practices in Dutch, Spanish, German, and French settlements, not to mention the built environments of Native or African-American peoples.[6]

The records for keyword terms vary considerably in length, in part because of the ubiquity of certain features (walk and fence, for instance) as opposed to those found only in a small number of designed landscapes (for example, grotto and deer park). In some cases, a record is brief because the term it covers became significant in landscape-design vocabulary late in the period covered by this study. In still other cases, the term was rarely used in the historical period under study but has become important in the writing of landscape history, albeit anachronistically (for example, ferme ornée and “folly”).

The range in quantity of material is also due to the nature of garden discourse. Most travelers’ accounts and descriptions in letters were more likely to comment on the particular features seen in a garden, such as the fish pond or garden mount, than wax eloquent on the advantages of the beautiful over the sublime or detail the distinguishing characteristics of the English style versus the Dutch. On the other hand, privies, although often decorative and a significant feature in the landscape (as at Poplar Forest and in the Yale University campus design), usually go unmentioned, perhaps for reasons of decorum. Many records, particularly those in deeds or advertisements, merely mention the presence of a garden and occasionally its most prominent features, offering little detailed description and even less commentary. As a result, the entries for style terms tend to be informed more heavily by garden treatises, which were promoting the concept of particular garden styles, and by a few individuals, such as Thomas Jefferson, who were well versed in aesthetic debates and applied the principles to their own gardening endeavors.

The selection of Keywords embraces a spectrum of landscape design terms. Entries on topographic forms such as mound and slope and water features such as pond and basin explicate some of the basic building blocks of landscape design. Those on circulation routes such as walk, avenue, and drive elucidate how a visitor’s progression through the landscape was manipulated. Terms related to the organization of vision, such as prospect, view, and eminence, reveal the visual logic of gardens and the importance of perception in the American landscape experience. Structures for keeping plants and animals, such as hothouse, green-house, and dovecote, bring to the fore the intimate relationships of botanical knowledge, climate, technology, and husbandry to landscape design. By including terms such as orchard, yard, lawn, and beehive, the project addresses a variety of gardens from across the socioeconomic spectrum and includes a range of what are often counted as vernacular landscapes. Terms such as kitchen garden and icehouse speak to the intersection of domestic landscape design and changing market conditions in the early years of the nation.

By including terms often associated with the public sphere, such as common, green, and square, the project also addresses the changing space of cities and towns and the issues surrounding their development. Landscape types such as botanic garden, burying ground, and park represent the diverse applications of landscape design and the variety of spaces that informed American landscape aesthetics. Planting arrangement terms such as shrubbery, wilderness, and grove reveal the complex and often misunderstood specific meanings of these important landscape design elements. Terms for ornaments such as urn, vase, statue, and sundial highlight the importance of decorative objects that were often made of perishable material and have rarely survived. Stylistic terms help to penetrate the intricacies of aesthetic theory and changing fashion in landscape design taste.[7]

A premise of this project has been to be as inclusive as possible, with the aim of expanding not only the amount of information available on early American gardens, but also the range of garden types and the number of sites used as evidence for American garden history. The kinds of sources consulted, both verbal and visual, are as varied as possible. Images found on samplers and painted fire screens offer different perspectives on the representation of the American landscape as compared with the background of a commissioned portrait by a trained artist. So too, accounts in advertisements, deeds, and insurance records provide very different views from those found in Jefferson’s musings on his landscaping efforts at Monticello or in Timothy Dwight’s record of his travels through New England. The best-known sites, such as Mount Vernon, Montgomery Place, the Mall in Washington, Monticello, Belfield, Crowfield, Elgin Botanic Garden, the University of Virginia, the Vale, and John Bartram’s garden, still contribute an invaluable quantity of descriptions, documents, and images, but HEALD goes beyond these canonical landscapes to include sites of modest size and simple design.

This illustrated historical resource takes as one of its greatest tools, and yet one of its greatest challenges, the connection of word and image with the ultimate goal of elucidating the meaning of both. And yet, this recursive relationship of playing word against image and image against word highlights the subjectivity of both forms of representation. It calls to the fore the importance of the context of the image or the “speech act,” to borrow a phrase from linguistics, in the construction of the meaning of those visual and textual accounts. The variety of voices represented—the court officer concerned with a boundary dispute, the owner of a property for sale, the ambitious gardener, the clergyman promoting the security and prosperity of a young democracy—expands the scope of American landscape history.

But, by including anonymous articles, unknown artists, and otherwise obscure authors, the project opens itself up to the challenges of interpreting sources with little-known context. Thus, the entries are preceded by three introductory essays that relate the sites and the primary sources to broader currents of American landscape design history. The addition of Place and People pages to the database is made possible by the richness of the documentary evidence the project has amassed. While they are limited in number, they are wide ranging in the types of sites they examine and the various roles—proprietor, landscape designer, enslaved gardener—that they highlight. In this, the Places and People pages are exemplary in their breadth of consideration of the subject.

A Guide to Using HEALD

Beyond background information and navigational elements, HEALD has several components accessed through the top menu bar: Introductory essays; the three Categories of Keywords, Places, and People, as well as Keyword Subjects; and Bibliography (the latter of which is located under the “About” tab). Within each Keyword, Place, or People page, the user can access further access images and primary and secondary references.

Introductory Essays: The first essay, by Therese O’Malley, focuses on the history of the sites themselves, relating changing design practices to the broader social and cultural currents of American landscape and garden history. Elizabeth Kryder-Reid, in the second essay, discusses the textual sources for landscape history, examining both the history of the sources and the theoretical aspects of issues to be addressed when using documentary evidence for garden history. The third essay, by Anne L. Helmreich and Therese O’Malley, discusses the visual representation of the American landscape, including both the theoretical challenges of interpreting visual evidence and the history of landscape images in America.

Keywords: Each of the one hundred Keywords records includes an interpretive essay that discusses the shifts in the term’s historical meaning and usage. The essay traces, where possible, the design history of each keyword, including its form, function, and materials, while it raises issues of the social and cultural significance of the landscape feature. It is followed by the primary documents, drawn from wide range of verbal sources, such as diaries, correspondence, travel accounts, garden treatises, dictionaries, legal records, advertisements, and periodical literature.

On Keywords pages, text is subdivided to highlight the difference between common and prescriptive usage. “Usage” quotations contain the term in common language such as letters, inventories, surveys or diaries, while “citations” contain generally published definitions, treatises and dictionaries. This dichotomy often reveals regional varieties and changes over time as a professional vocabulary evolves.[8] Each primary source is identified by a short citation of the bibliographical reference with full citations in the endnotes and linked to the project bibliography.

Images providing visual evidence for each entry, which were compiled from diverse media including paintings, prints, maps, textiles, drawings, and painted furniture and ceramics, appear throughout. Each image has its own object page that provides information about the artist, title, date, media, and source or repository. This feature in itself represents an unprecedented corpus of American garden imagery.

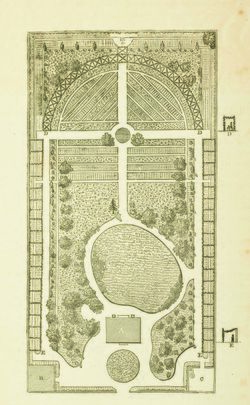

The degree of certainty with which words may be associated with images varies, so throughout the Keywords pages of HEALD a concerted effort has been made to use the most secure associations possible. Each caption includes, along with the above information, an indication of how the image and term relate to one another. To this end, there are three designations used within the gallery of images: inscribed, associated, and attributed. An “inscribed” image incorporates the word or is directly related to it through a key or an immediately accompanying text such as a caption or a description of the site published with the image. For example, The Horticulturist published a “Plan of a Suburban Garden” (taken from “an elaborate French work”) with an accompanying article which describes the site using the letters on the plan as orientation points [Fig. 1].[9]

An “associated” image is related to the term less directly by a contemporaneous description of the feature or an inscribed image of the same feature. For example, two engravings of Monte Video are published in Benjamin Silliman’s Remarks Made on a Short Tour between Hartford and Quebec, which includes a description of the site, specifically commenting on the lake and the tower, both visible in one of the prints [Fig. 2].[10] A range of certainty exists in linking an image with an associated text. For example, Mount Vernon, a landscape that was continually modified, was visited and recorded by numerous visitors over the years, making it difficult at times to determine whether a particular feature described in a text is the same one depicted in an image.

The third category, “attributed” images, are those for which there are no inscribed terms or associated texts [Fig. 3]. Identification of the garden features visible in these images is based on comparative examples. The problems with interjecting modern identifications are not inconsequential and are discussed in more depth in the essay on visual representation of the landscape, but these attributed images offer the opportunity to include a range and variety of works not otherwise accessible. In this category are imaginary, allegorical, or instructive images that are often revealing of principles of landscape design and representation, even if they are not records of executed designs. Also in this category are naïve art and textiles, often by unknown artists, as well as lesser-known images from painted furniture, ceramics, and wall murals.

People and Places: Throughout the database, a selection of people and place names are hyperlinked to their own pages. The pages for People provide brief historical essays on a range of individuals of particular note or interest in which their relation to the theory and practice of early American gardens and landscapes design is discussed. The Place pages include historical essays on a selection of gardens or landscapes, in which key features, events, or associated figures are discussed. How the site evolved over time and, when possible, a statement of the site’s current condition, and geographic coordinates are included. The essays for both People and Place pages are followed by citations and a gallery of images related to the subject of the page. Other resources include links to relevant external websites and maps when appropriate.

Keyword Subjects: This general search function under “categories” in the menu bar assists in both browsing by design genres and also locating a term for which the reader has an illustration but no name. In the case of the latter, the entries for “plant-keeping structure” or “water feature” direct the reader to specific types of garden structures such as orangery, hothouse, and conservatory, or to types of water features such as basin, canal, fountain, and pond.

Bibliography The extensive bibliography comprises all published and manuscript sources used in this project. It was built with Zotero, a free, open-source reference software that can manage bibliographic data and related research materials. It many cases it links to digitized editions of the primary sources. Furthermore, the user can add the source to one’s own personal Zotero library.

Taken as a whole, the HEALD website provides both an overview and in-depth resource of key terms, places in public, private, and institutional realms, and a wide array of people—designers, writers, patrons, artists, theorists, professionals, and amateurs—that together contribute to a rich and vibrant picture of a significant chapter in the history of American garden and landscape design in the colonial, early national, and antebellum periods.

Notes

- ↑ Raymond Williams, Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society (New York: Oxford University Press, 1976), view on Zotero. Two other books, both written by advisors to the project, served as models: Michel Conan, Dictionnaire Historique de l’Art des Jardins (Paris: Hazan Editions, 1997), view on Zotero, and Carl R. Lounsbury, ed., An Illustrated Glossary of Early Southern Architecture and Landscape (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), view on Zotero.

- ↑ In order to keep the scope of the project within reasonable limits, species names, botanical terms, and other words relating to plant material were not included. Verbs related to the maintenance, propagation, and construction were also not considered (ex., “pleach,” “prune,” “topiary”), except as examples such as espalier and walk where the verbs are synonymous with design features. Terms related more strictly to agriculture and husbandry were also excluded, although some, such as “barn,” “dairy,” “field,” and “springhouse,” were clearly integral to certain aspects of designed landscapes. A distinction was also made between descriptions of the natural scenery or the general countryside, albeit “improved,” and those of intentional designed landscapes. While the vocabulary of descriptions for the two types of landscape is often similar (see works listed in the bibliography by William Bartram and by William Wood), and while many of the same conventions and themes are evident in such writings, HEALD focuses on the particular context of the designed spaces. For an influential discussion of landscape types, see John Dixon Hunt, Gardens and the Picturesque: Studies in the History of Landscape Architecture (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1992), 1–4, view on Zotero.

- ↑ For Canadian sources, see Edwinna von Baeyer, A Selected Bibliography for Garden History in Canada (Ottawa: Environment Canada-Parks, National Historic Parks and Sites Branch, 1987), view on Zotero.

- ↑ In these cases, the bibliographic reference reflects the published secondary source from which the primary source was taken.

- ↑ Scholars who contributed original research include Carl Lounsbury, Barbara Wells Sarudy, Helen Tangires, and Dell Upton.

- ↑ The richness of American landscape design is clearly indebted to the heterogeneous influences of diverse European gardening traditions and Native American practice. Further research is needed concerning Native American precedents and the Dutch, German, Spanish, Portuguese, and French landscape design vocabulary and influence in colonial and early America.

- ↑ Within each of these term categories are many words that were not included. For instance, vase, urn, and pot are included but not “box.” Ice-house is included but not “dairy” or “spring-house.” English and French styles are included, but not “Italian.” Seat is included but not “bench.” In each case the selection of terms reflects the richness of the record of primary sources and the term’s relevance to the history of American landscape design while representing the broadest array of design vocabulary possible.

- ↑ The treatises and dictionaries include European and American publications, although only those sources known to have been available in America before 1852 were consulted. See Kryder-Reid essay for further discussion of American garden literature.

- ↑ Anonymous, “Design for a Suburban Garden,” The Horticulturist 3, no. 8 (February 1849): 380, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Benjamin Silliman, Remarks Made on a Short Tour Between Hartford and Quebec, in the Autumn of 1819 (New Haven, CT: S. Converse, 1824); see description on pages 11 and 15 and the illustration bound between pages 16 and 17, view on Zotero.