J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon

Overview

Birth Date: April 8, 1783

Death Date: December 14, 1843

Role: Landscape designer, Architect

Used Keywords: Alcove, Ancient style, Arbor, Aviary/Bird cage/Birdhouse, Basin, Bed, Beehive, Belvedere/Prospect tower/Observatory, Botanic garden, Bower, Bridge, Cascade/Cataract/Waterfall, Chinese manner, Clump, Conservatory, Dutch style, Edging, Espalier, Fence, Ferme ornée/Ornamental farm, Flower garden, Fountain, French style, Gardenesque, Gate/Gateway, Geometric style, Grotto, Hedge, Hothouse, Icehouse, Kitchen garden, Lake, Landscape gardening, Lawn, Modern style/Natural style, Mound, Mount, Orangery, Park, Parterre, Pavilion, Picturesque, Plantation, Pleasure ground/Pleasure garden, Pond, Porch, Portico, Pot, Public garden/Public ground, Rockwork/Rockery, Rustic style, Seat, Shrubbery, Square, Statue, Temple, Terrace/Slope, Thicket, Trellis, Vase/Urn, View/Vista, Walk, Wall, Wood/Woods

Other resources: Library of Congress Authority File; Getty ULAN; Oxford Dictionary of National Biography;

John Claudius Loudon (April 8, 1783–December 14, 1843) was a Scottish botanist, landscape architect, cemetery designer, and author, as well as the most influential horticultural journalist of his time. Through an extraordinarily prolific publishing career, Loudon raised popular knowledge of and interest in botany, horticulture, and agriculture while shaping contemporary taste in gardens, public parks, and domestic architecture throughout Britain, America, and much of the Western world.[1]

History

As a young man, Loudon worked part-time for nurserymen and landscape gardeners near Edinburgh while pursuing the study of animal husbandry, gardening, and agriculture. On moving to London in 1803, he swiftly established his authority as a practitioner and theorist of landscape gardening and even dabbled in landscape painting, exhibiting five works at the Royal Academy of Arts between 1804 and 1817.[2] In addition to the study of art, his taste owed much to the reading of classical and modern writers, particularly English poets and aesthetic theorists. Uvedale Price, one of the principal theorists of the picturesque, was especially influential; Loudon later observed, “I believe that I am the first who has set out as a landscape gardener, professing to follow Mr. Price’s principles.”[3] Loudon’s plan for improving the public squares of London through picturesque plantings of trees and shrubs, published in the Literary Journal in 1803, initiated a voluminous outpouring of articles, books, and pamphlets that would occupy him for the rest of his life.[4]

Loudon traveled extensively in order to familiarize himself with the ornamental and agricultural use of land in Britain and continental Europe. Impressed by the productivity of Russian hothouses during a trip to Scandinavia and Eastern Europe (1813–14), he began experimenting with the use of curved iron and glass in innovative hothouse structures that could be adjusted to the changing angle of the sun’s rays [Fig. 1].[5] In 1819 he visited France, Italy, Switzerland, and the Low Countries to gather material for An Encyclopaedia of Gardening: Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture and Landscape-gardening (1822)—by far the most comprehensive and systematic compendium of gardening information that had been published at the time. In contrast to many of Loudon’s previous publications, which were expensively produced and richly illustrated, the Encyclopaedia of Gardening was a practical guide intended for professional gardeners and middle-class amateurs rather than elite readers. As such, it established a new direction in garden literature that Loudon continued to develop in subsequent publications, such as Encyclopaedia of Cottage, Farm, and Villa Architecture (1833) and The Suburban Gardener and Villa Companion (1838).[6]

Landowners throughout England and Scotland sought Loudon’s advice on improving the grounds of their estates.[7] Following his marriage in 1830, he was greatly assisted by his wife, Jane Webb Loudon, who became an important gardening authority in her own right.[8] In 1826 Loudon launched Gardener’s Magazine—the first periodical devoted solely to horticulture—which aimed “to disseminate new and important information on all topics connected with horticulture and to raise the intellect and the character of those engaged in this art.”[9] Addressed to an expanding middle-class audience, the magazine became an international forum for the exchange of specialized information on scientific discoveries, technological improvements, aesthetic theories, and working designs.[10] An article Loudon published in the magazine in 1832 established the term “Gardenesque” to denote a deliberately artificial style of garden layout that lent itself to botanical study of individual plant specimens, revealing the art of the gardener as well as the beauty of nature [Fig. 2].[11] Whereas earlier landscape artists had “looked on garden scenery entirely with the eye of a painter and a poet,” Loudon believed that “the modern artist adds to these the eye of the botanist and the cultivator.”[12]

Loudon’s most important work in the Gardenesque style is the Derby Arboretum (1839–41)—generally considered England’s first public park—which he designed with over one thousand different varieties of trees and shrubs.[13] Among Loudon’s numerous horticultural publications, the most ambitious was his copiously illustrated (and financially ruinous) eight-volume “paper arboretum,” the Arboretum et Fruticetum Britannicum (1835–38): a survey of all the trees and shrubs then growing in Britain, which he hoped would spur a taste for arboriculture and the cultivation of a greater variety of trees.[14]

—Robyn Asleson

Texts

Books

An Encyclopaedia of Gardening, 4th ed. (1826)

J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, 4th ed. (London: Longman et al., 1826)[15] View at Internet Archive

An Encyclopaedia of Gardening, new ed., improved and enlarged (1834)

J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, new ed., considerably improved and enlarged (London: Longman et al., 1834)[16] View at Hathi Trust

The Suburban Gardener (1838)

J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, The Suburban Gardener, and Villa Companion (London: Longman et al, 1838)[17] View at Internet Archive

An Encyclopaedia of Gardening, new ed., corrected and improved (1850)

J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, a new ed., corr. and improved (London: Longman et al., 1850)[18] View at Hathi Trust

Journals

Gardener’s Magazine

- 1832, Review of Practical Hints on Landscape Gardening (Gardener’s Magazine 8: 701–2)[19]

- “In our opinion, a landscape-gardener knows but a part of his profession, who is not conversant with the numerous families of American and other trees which will thrive in the open air in Britain. Mere picturesque improvement is not enough in these enlightened times: it is necessary to understand that there is such a character of art as the gardenesque, as well as the picturesque. The very term gardenesque, perhaps, will startle some readers; but we are convinced, nevertheless, that it is a term which will soon find a place in the language of rural art. Landscape-gardening, it will be allowed, is, to a certain extent, an art of imitation. Now, an imitative art is not one which produces facsimiles of the things to be imitated; but one which produces imitations, or resemblances, according to the manner of that art. Thus, sculpture does not attempt colour, nor painting to raise surfaces in relief; and neither attempt to deceive. In the like manner, the imitator, in a park or pleasure-ground, of a landscape composed of ground, wood, and water, does not produce facsimiles of the grounds, wood, and water, which he sees around him on every side; but, of ground, wood and water, arranged in imitation of nature, according to the principles of his particular art. The character of this art has varied from the earliest times to the present day; but profoundly examined, the principle which guided the artist remains the same; and the successive fashions that have prevailed will be found to confirm our views of the subject, viz., that all imitations of nature worthy of being characterized as belonging to the fine arts art not facsimile imitations, but imitations of manner. To apply this principle to the planting of trees in park or pleasure-ground scenery nature, in any given locality, makes use of a certain number of trees found indigenous there; but the garden imitator of natural woods introduces either other forms and dispositions of the same kinds of trees, as in the geometric style; or the same disposition of other species of trees, as in the most improved practice of the modern style. In neither case does the artist produce a correct facsimile of nature; for, if he did, however beautiful the scene copied, the beauty produced would be merely that of repetition. But we have neither room nor time at present fully to illustrate this theory. Let it suffice for us to state, for the consideration of those of our readers who have reflected on the subject, that there is as certainly, in gardening, as an art of imitation, the gardenesque, as there is, in painting and sculpture, the picturesque and sculpturesque.”

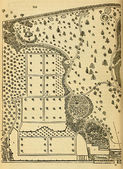

- December 1839, describing Cheshunt Cottage, property of William Harrison, near London, England (Gardener’s Magazine 15: 644, 653, 667–68)[20]

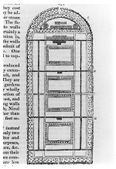

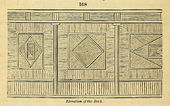

- “3. The orangery. The paths are of slate, and the centre bed, or pit, for the orange trees, is covered with an open wooden grating, on which are placed the smaller pots; while the larger ones, and the boxes and tubs, are let down through openings made in the grating, as deep as it may be necessary for the proper effect of the heads of the trees. This house, and that for Orchidàceæ, are heated from the boiler. . . . [Fig. 72]

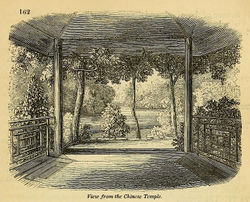

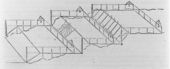

- “85, Double ascent of the steps to a mound formed of the earth removed in excavating for the pond. From the platform to which these steps lead, there is a circuitous path to the Chinese temple, and the steps are ornamented with Chinese vases, thus affording a note of preparation for the Chinese temple. The outer sides of the steps are formed of rockwork, and between the two stairs is a pedestal with Chinese ornaments.

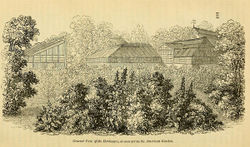

- “86, The Chinese temple, on the highest part of the mount formed of the soil taken from the excavation now constituting the pond. The view from the interior of this temple is shown in fig. 162. . . . [Fig. 73]

- “The masses of trees and shrubs are chiefly on the mount near the lake, and along the margin which shuts out the kitchen-garden; and in these places they are planted in the gardenesque manner, so as to produce irregular groups of trees, with masses of evergreen and deciduous shrubs as undergrowth, intersected by glades of turf. they are scattered over the general surface of the lawn, so as to produce a continually varying effect, as viewed from the walks; and so as to disguise the boundary, and prevent the eye from seeing from one extremity of grounds to the other, and thus ascertain their extent.” [Fig. 74]

Images

An Encyclopaedia of Gardening, 4th ed. (1826)

J. C. Loudon, "The pleasure-ground", in An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826), 1021, fig. 719.

An Encyclopaedia of Gardening, new ed., improved and enlarged (1834)

The Suburban Gardener (1838)

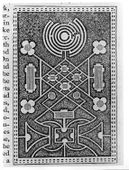

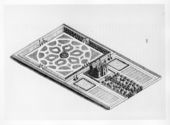

J. C. Loudon, “Trees . . . arranged in the gardenesque manner,” in The Suburban Gardener (1838), 165, fig. 47.

Gardener’s Magazine (December 1839)

An Encyclopaedia of Gardening, new ed., corrected and improved (1850)

Other Resources

Notes

- ↑ Paul Elliott, Charles Watkins, and Stephen Daniels, “‘Combining Science with Recreation and Pleasure’: Cultural Geographies of Nineteenth-Century Arboretums,“ Garden History 35 (2007): 9–10, view on Zotero; Colleen Morris, “The Diffusion of Useful Knowledge: John Claudius Loudon and His Influence in the Australian Colonies,” Garden History 32, no. 1 (Spring 2004): 101–23, view on Zotero; Margaretta J. Darnall, “The American Cemetery as Picturesque Landscape: Bellefontaine Cemetery, St. Louis,” Winterthur Portfolio 18, no. 4 (Winter 1983): 264–65, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Melanie Louise Simo, Loudon and the Landscape: From Country Seat to Metropolis, 1783–1843 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988), 1–7, 28–29, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Laurence Frickler, “John Claudius Loudon: The Plane Truth?,” in Furor Hortensis: Essays on the History of the English Landscape Garden in Memory of H. F. Clark, ed. Peter Willis (Edinburgh: Elysium Press Limited, 1974), 81, view on Zotero; see also Simo 1988, 38–45, 52–56, 93–95, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Frickler 1974, 76–88, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Claudius Loudon, Remarks on the Construction of Hothouses, Pointing out the Most Advantageous Forms, Materials, and Contrivances to Be Used in Their Construction; Also, A Review of The Various Methods of Building Them in Foreign Countries as Well as in England (London: J. Taylor, 1817) view on Zotero; Georg Kohlmaier and Barna von Sartory, Houses of Glass: A Nineteenth-Century Building Type (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1991), view on Zotero; Simo 1988, 7–9, 110–18, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Andrea Henderson, “Mastery and Melancholy in Suburbia,” Eighteenth Century 50, no. 2/3 (Summer–Autumn 2009): 227–31, view on Zotero; Simo 1988, 9, 147–48, view on Zotero; see also Sarah Dewis, The Loudons and the Gardening Press: A Victorian Cultural Industry (Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2014), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Simo 1988, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Claudius Loudon, In Search of English Gardens: The Gravels of John Claudius Loudon and His Wife Jane, ed. Priscilla Boniface (Wheathampstead: Lennard Publishing, 1987), 10–16, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Quest-Ritson, The English Garden: A Social History (London: Viking Press, 2001), 177, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Simo 1988, 153–62, view on Zotero; Ray Desmond, “Loudon and Nineteenth-Century Horticultural Journalism” in John Claudius Loudon and the Early Nineteenth Century in Great Britain, ed. Elisabeth MacDougall (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks, 1980), 79–82, 94–96 view on Zotero.

- ↑ Simo 1988, 171–75, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Claudius Loudon, The Suburban Gardener, and Villa Companion (London: Longman et al., 1838), 638, view on Zotero; see also Heath Schenker, “Women, Gardens, and the English Middle Class in the Early Nineteenth Century” in Bourgeois and Aristocratic Cultural Encounters in Garden Art, 1550–1850, ed. Michel Conan (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks, 2002), 338n, 343–47, 356–60, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Beryl Hartley, “Sites of Knowledge and Instruction: Arboretums and the ‘Arboretum et Futicetum Britannicum,’” Garden History 35 (2007): 35–36, view on Zotero; Elliott, Watkins, and Daniels 2007, 20–22, view on Zotero; Hilary A. Taylor, “Urban Public Parks, 1840–1900: Design and Meaning,” Garden History 23, no. 2 (Winter 1995): 203–6, view on Zotero; John Claudius Loudon, The Derby Arboretum: Containing a Catalogue of the Trees and Shrubs Included in It, A Description of the Grounds and Directions for Their Management, A Copy of the Address Delivered When It Was Presented to the Town of Derby . . . on Sept. 16, 1840 (London: Longman, Orme, Brown, Green & Longmans, 1840), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Hartley 2007, 28–52, view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, 4th ed. (London: Longman et al., 1826), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, new ed., considerably improved and enlarged (London: Longman et al., 1834), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Loudon 1838, view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, a new ed., corr. and improved (London: Longman et al., 1850), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. Loudon, “Review of Practical Hints on Landscape Gardening, Gardener’s Magazine and Register of Rural & Domestic Improvement 8, no. 41 (December 1832): 700–2, view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. Loudon, “Descriptive Notices of Select Suburban Residences, with Remarks on Each; Intended to Illustrate the Principles and Practices of Landscape-Gardening,” Gardener’s Magazine and Register of Rural & Domestic Improvement XV, no. 117 (December 1839): 633–74, view on Zotero.