Difference between revisions of "Robert Mills"

m |

m |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

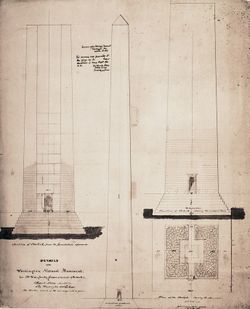

[[File:0830.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 1, Robert Mills, Details of the Washington Monument for Mr. Daugherty, Superintendent of the Work, Washington, DC, October 24, 1848.]] | [[File:0830.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 1, Robert Mills, Details of the Washington Monument for Mr. Daugherty, Superintendent of the Work, Washington, DC, October 24, 1848.]] | ||

| − | + | In approximately 1800, Mills left his native Charleston, South Carolina, to work under the architect James Hoban (c. 1758–1831) on the President’s House in the city of Washington. There, Mills became acquainted with [[Thomas Jefferson]], who lent him European books on architecture and in 1803 recommended him for a place in the office of [[Benjamin Henry Latrobe]], who was then designing a [[canal]] in the vicinity of the future [[National Mall]] while also overseeing work at the President’s House and the U.S. Capitol.<ref>John M. Bryan, ed. ''Robert Mills, Architect'' (Washington, DC: American Institute of Architects Press, 1989), 1–8, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/NQCC9937 view on Zotero]; John M. Bryan, ''Robert Mills: America’s First Architect'' (Princeton, NJ: Princeton Architectural Press, 2001), 6–35, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/P55UM5XC view on Zotero]; Rhodri Windsor Liscombe, ''Altogether American : Robert Mills, Architect and Engineer, 1781–1855'' (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 3–30, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/NGNZ65WN view on Zotero].</ref> Both [[Benjamin Henry Latrobe|Latrobe]]’s civil engineering work and his modern interpretation of ancient Greek and Roman architecture had lasting effects on Mills’s career. | |

In 1814 Mills won an important competition to design the [[Washington Monument (Baltimore)|Washington Monument]] in Baltimore, Maryland, which was to be the first public monument dedicated to the memory of [[George Washington]]. <span id="Mills_birth_cite"></span>In advancing his candidacy, Mills had emphasized his American birth and education, noting that his architectural training had been “altogether American and unmixed with European habits" ([[#Mills_birth|view citation]]).<ref>William D. Hoyt Jr., “Robert Mills and the Washington Monument in Baltimore [Part One],” '' Maryland Historical Magazine'' 34 (1939): 153, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/DC2JN4I5 view on Zotero]; J. Jefferson Miller, “The Designs for the Washington Monument in Baltimore, ''Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians'' 23, no. 1 (March 1964): 23, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/5VX37FEW view on Zotero]; Bryan 2001, 112, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/P55UM5XC view on Zotero].</ref> Mills’s knowledge of ancient and modern European art and architecture was actually quite extensive, and he drew freely on Old World prototypes in designing his landmark American monument, which ultimately took the form of a colossal Doric [[column]] on a cubic base surmounted by a [[statue]] of [[George Washington|Washington]] [Fig. 1].<ref>Pamela Scott, “Robert Mills and American Monuments,” in ''Robert Mills, Architect,'' ed. John M. Bryan (Washington, DC: American Institute of Architects Press, 1989), 146–54, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/P55UM5XC view on Zotero].</ref> | In 1814 Mills won an important competition to design the [[Washington Monument (Baltimore)|Washington Monument]] in Baltimore, Maryland, which was to be the first public monument dedicated to the memory of [[George Washington]]. <span id="Mills_birth_cite"></span>In advancing his candidacy, Mills had emphasized his American birth and education, noting that his architectural training had been “altogether American and unmixed with European habits" ([[#Mills_birth|view citation]]).<ref>William D. Hoyt Jr., “Robert Mills and the Washington Monument in Baltimore [Part One],” '' Maryland Historical Magazine'' 34 (1939): 153, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/DC2JN4I5 view on Zotero]; J. Jefferson Miller, “The Designs for the Washington Monument in Baltimore, ''Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians'' 23, no. 1 (March 1964): 23, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/5VX37FEW view on Zotero]; Bryan 2001, 112, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/P55UM5XC view on Zotero].</ref> Mills’s knowledge of ancient and modern European art and architecture was actually quite extensive, and he drew freely on Old World prototypes in designing his landmark American monument, which ultimately took the form of a colossal Doric [[column]] on a cubic base surmounted by a [[statue]] of [[George Washington|Washington]] [Fig. 1].<ref>Pamela Scott, “Robert Mills and American Monuments,” in ''Robert Mills, Architect,'' ed. John M. Bryan (Washington, DC: American Institute of Architects Press, 1989), 146–54, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/P55UM5XC view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

Revision as of 16:29, October 5, 2018

Robert Mills (August 12, 1781–March 3, 1855) was an American engineer and architect best known for designing the Washington Monument in Washington, DC. He was responsible for some of America’s earliest commemorative monuments, as well many public buildings in the nation’s capital and elsewhere. His blend of Palladian, Georgian, and Greek Revival styles contributed to the development of a distinctive Federal mode of architecture.

History

In approximately 1800, Mills left his native Charleston, South Carolina, to work under the architect James Hoban (c. 1758–1831) on the President’s House in the city of Washington. There, Mills became acquainted with Thomas Jefferson, who lent him European books on architecture and in 1803 recommended him for a place in the office of Benjamin Henry Latrobe, who was then designing a canal in the vicinity of the future National Mall while also overseeing work at the President’s House and the U.S. Capitol.[1] Both Latrobe’s civil engineering work and his modern interpretation of ancient Greek and Roman architecture had lasting effects on Mills’s career.

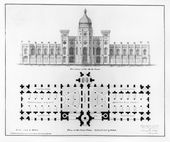

In 1814 Mills won an important competition to design the Washington Monument in Baltimore, Maryland, which was to be the first public monument dedicated to the memory of George Washington. In advancing his candidacy, Mills had emphasized his American birth and education, noting that his architectural training had been “altogether American and unmixed with European habits" (view citation).[2] Mills’s knowledge of ancient and modern European art and architecture was actually quite extensive, and he drew freely on Old World prototypes in designing his landmark American monument, which ultimately took the form of a colossal Doric column on a cubic base surmounted by a statue of Washington [Fig. 1].[3]

The Baltimore commission created opportunities to work on a number of smaller monuments. Mills designed an Egyptian Revival obelisk for the Aquilla Randall Monument (1816–17) in Baltimore and he repeated the obelisk form in subsequent commemorative projects, including the De Kalb (1824–27) and Maxcy Monuments (1824–27) in South Carolina,[4] as well as a drawing he submitted in 1825 for the competition to design the Bunker Hill Monument in Charleston, Massachusetts. Mills’s series of memorial monuments culminated in the most ambitious public monument to honor of Washington, the Washington Monument on the National Mall in Washington, DC. Mills had proposed a variety of architectural projects in the President’s memory following his move to Washington in 1830, but it was not until 1845 that he secured the commission, and the monument was not completed until 30 years after his death.[5]

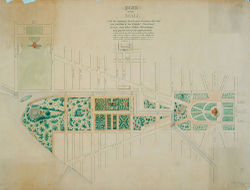

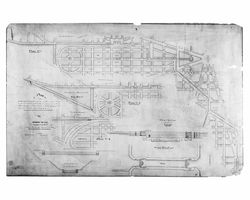

From early in his career, Mills had tailored many of his architectural and civil engineering projects to address the need for public recreation, urban green space, and landscape improvement. While serving as president of the Baltimore Water Company (1816–17), he devised a plan for improving the city’s waterways that included tree-lined promenades (with “romantic scenery and waterfalls") for public recreation.[6] The recommendations Mills made for developing canals in South Carolina in the early 1820s included lengthy discussions of the canals’ impact on daily life.[7] In 1831, commissioned to redesign the Washington canal [Fig. 2], he expanded his purview to include the entire Mall, which he accommodated to a grid plan—a scheme he revised ten years later when he designed a Botanic Garden and the Smithsonian Institution building on the Mall.[8] Mills’s meticulously detailed 1841 plans conceived of the National Mall as a didactic as well as a recreational space in which specimen plantings were laid out in an assemblage of gardens of contrasting styles, interlinked above ground by pleasantly meandering paths and underground by pipes providing water for irrigation and ornamental fountains. Mills’s designs for the National Mall have been interpreted as “part of an ambition to create a city-wide ‘museum’ of architecture and taste in Washington.”[9] The National Mall was just one of several architectural and engineering projects that Mills undertook in the nation’s capital, the number and variety of which conferred on him the status of “unofficial federal architect.”[10]

—Robyn Asleson

Texts

- Mills, Robert, c. 1804, describing the National Mall (quoted in Gallagher 1935: 1927)[11]

- “It is a most commanding and beautiful prospect, variegated with woods, cleared land, gentle mounts and vales, and the waters of the Potomac and Tiber Rivers in the distant view; while there is revealed a glimpse of the navy yard where eight frigates of the United States Navy lie in mooring.”

- Mills, Robert, November 1813, initial proposal for the [[Washington Monument (Baltimore, MD), Baltimore (quoted in Hoyt 1939: 145–46)[12]

- “To the memory of General Washington, to be erected in the city of Baltimore, of octagonal form from the base to the top. . . .

- “From the base upwards to the first offset of the column eight feet, to be wrought at each angle the half of an octagonal pillar, cut diagonally nine inches diameter & both at the base and eight feet distant at the offset to be formed from angle to angle a cornice in the Tuscan order. . . .

- “The space or yard contiguous to the base of the column to be of diagonal 42 2/3 feet diameter, corresponding with the angles of the monument. . . .

- “On the East, West, North and South of the monument to be placed two gate posts with a gate. Over the gate way to be suspended an elegant arch, consisting of white marble, the two ends resting on the to posts of each gate, bearing over the centre of each gate on the front of the arch the arms of the United States. All around the yard, which incloses the monument, to be formed a gravel walk, eleven feet in width, surrounded by an open fence of wooden posts and &railing, painted white with vacant spaces for entrance, opposite the gates.”

- Mills, Robert, 1814, in the accompanying letter to his proposal for the [[Washington Monument (Baltimore, MD) (quoted in Hoyt 1939: 153)[12] back up to History

- “Being an American by Birth and having also the honor of being the first American who has passed through a regular course of Study of Architecture in his own Country, it is natural for me to feel much Solicitude to aspire to the honor of raising a Monument to the memory of our illustrious Countryman. The Education I have received being all together American and unmixed with European habits, I can safely present the design submitted as American founded upon those general principles prefaced in the description contained in the Book of Designs.”

- Mills, Robert, 1814, formal statement of his plan for the [[Washington Monument (Baltimore, MD) (quoted in Hoyt 1939: 154–55)[12]

- “In laying the designs herewith submitted, before you, I would beg leave to make a few remarks upon Monuments in general, before I proceed to describe the one I have the honor now to present.

- “The character that ought to designate all Monuments should be, solidity, simplicity, and that degree of cheerfulness which should tempt the contemplation of the mind. . . . Monuments isolated, or in the open air, should be towering, and commanding in their elevation, especially when they are encircled by a City, otherwise its popular intention is frustrated. . . . Permit me now to draw your attention to the description of the design in question:—The Mass, presents the appearance of a Greek Column, elevated on a grand pedestal; the column assumes the doric proportions, which possess solidity, and simplicity of character, emblematic of that of the illustrious personage to whose memory it is dedicated, and harmonising with the spirit of our Government. . . .

- “Arrived at the platform which crowns this pedestal, and which is inclosed by a balustrade, we see the commencement of the great Column. The diameter of this is more than 20 feet and its elevation above 120 ft. divided in its heigh by Six iron railed galleries, which encircle it like bands, presenting promenades to accommodate the reading of those historical inscriptions recorded on the shaft of the column.”

- Mills, Robert, March 20, 1825, in a letter to the Monument Commission, describing plans for the Bunker Hill Monument, Boston (quoted in Gallagher 1935: 204–6)[11]

- “I have the honor to submit for your consideration and approval, a design for the Monument you propose erecting on the spot, where the Brave General Warren and his worthy associates fell; to commemorate their valor, and the gratitude of their Country. . . .

- “In the design for the Monument which I now have the honor to lay before you, I would recommend the adoption of the obelisk form, in preference to the Column—the detail I have affixed to this species of pillar, will be found to give it a peculiarly interesting character, embracing originality of effect with simplicity of design, economy in execution, great solidity and capacity for decoration, reaching to the highest degree of splendor consistant with good taste. . . .

- “The obelisk form is, for monuments, of greater antiquity than the Column as appears from history, being used as early as the days of Ramises King of Egypt in the time of the Trojan War—Kercher reckons up 14 obelisk that were celebrated above the rest, namely, that of Alexandria; that of the Barberins; those of Constantinople; of the Mons Esquilinus; of the Campus Flaminius; of Florence; of Heliopolis; of Ludorisco; of St. Makut, of the Medici of the vatican; of M. Coelius, and that of Pamphila. The highest on record mentioned, is that erected by Ptolemy Philadelphus in memory of Arsinoe.

- “The obelisk form is peculiarly adapted to commemorate great transactions from its lofty character, great strength, and furnishing a fine surface for inscriptions—There is a degree of lightness and beauty in it that affords a finer relief to the eye than can be obtained in the regular proportioned Column.

- “Our monument includes a square of 24 feet at the base above the zocle or plinth, and is 15 feet square at the top—Its total elevation is 220 feet above the pavement—The shaft is divided into four great compartments for inscriptive, and other decorations, which come more immediately under the eye by means of oversailing platforms, enclosed by balastrades, supported as it were by winged globes (symbols of immortality peculiarly of a monumental Character).

- “A series of shields band round the foot of the shaft, representing the 13 States, which form'd the Federal union, as principal, having their arms sculptured on their face—A star, on a plain tablet in connection with the former, represents each the other states which now constitute our Union—the whole surmounted by spears and wreathes.

- “A flight of stone steps, or a rising platform, surround the base, from whence the lower inscriptions are read—

- “This is inclosed by a rich bronzed palisade—The entrance into the monument is from this platform, when a flight of stone steps, winding round a pillar, ascends to the top, and communicates with the several platforms. Between the galleries, on each face of the pillar, a wreath, hung on a speer, encircles the letter W, which is otherwise decorated and constitute apertures for lighting the interior of the Monument—over the Last wreath, and near the apex of the obelisk, a great star is placed, emblematic of the glory to which the name of Warren has risen—A tripod crowns the whole and forms the surmounting of the Monument—This tripod is the classic emblem of immortality.”

- Mills, Robert, July 1, 1832, in a letter to Richard Walleck, describing Charlestown, MA (quoted in Gallagher 1935: 102)[11]

- “When the Bunker Hill Monument Committee advertised for designs for the Monument, I took a good deal of pains to study one which should do honor to the memory of those worthies it was intended to commemorate, and prove an ornament to the city it was to overlook. I went into some detail on the subject of monuments generally and in sending them two designs, recommended in strong terms the adoption of the Obelisk design, not only from its combining simplicity and economy with grandeur, but as there was already a column of massy proportions erected in Baltimore, we ought not, therefore, to repeat this figure, but construct one of equally imposing figure.”

- Mills, Robert, 1836, arguing to increase the area around the [[Washington Monument (Baltimore, MD) (quoted in Lavoie 2005: 28)[13]

- “It would be a pity to have the space about the Mont [monument] cramped, after making the sacrifices that have been made—ample room here will be found not only ornamental but useful for many purposes, for the parade of troops, for great public meetings, etc.”

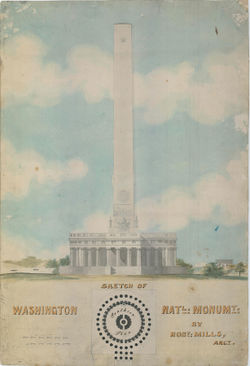

- Mills, Robert, c. 1838, description of his design of the [[Washington Monument (Washington, DC) (quoted in Harvey 1903: 26–28)[14]

- “DESCRIPTION OF THE DESIGN OF THE WASHINGTON NATIONAL MONUMENT, TO BE ERECTED AT THE SEAT OF THE GENERAL GOVERNMENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, IN HONOR OF ‘THE FATHER OF HIS COUNTRY,’ AND THE WORTHY COMPATRIOTS OF THE REVOLUTION.

- “This design embraces the idea of a grand circular colonnaded building, 250 feet in diameter and 100 feet high, from which springs a obelisk shaft 70 feet at the base and 500 feet high, making a total elevation of 600 feet.

- “This vast rotunda, forming the grand base of the Monument, is surrounded by 30 columns of massive proportions, being 12 feet in diameter and 45 feet high, elevated upon a lofty base or stylobate of 20 feet elevation and 300 feet square, surmounted by an entablature 20 feet high, and crowned by a massive balustrade 15 feet in height.

- “The terrace outside of the colonnade is 25 feet wide, and the pronaos or walk within the colonnade, including the column space, 25 feet. The walks enclosing the cella, or gallery within, are fretted with 30 massive antæ (pilasters) 10 feet wide, 45 feet high, and 7-1/2 feet projection, answering to the columns in front, surmounted by their appropriate architrave. The deep recesses formed by the projection of the antæ provide suitable niches for the reception of statues.

- “A tetrastyle portico (4 columns in front) in triple rows of the same proportions and order with the columns of the colonnade, distinguishes the entrance to the Monument, and serves as a pedestal for the triumphal car and statue of the illustrious Chief; the steps of this portico are flanked by massive blockings, surmounted by appropriate figures and trophies.

- “Over each column, in the great frieze of the entablatures around the entire building, are sculptured escutcheons (coats of arms of each State in the Union), surrounded by bronze civic wreaths, banded together by festoons of oak leaves, &c., all of which spring (each way) from the centre of the portico, where the coat of arms of the United States are emblazoned.

- “The statues surrounding the rotunda outside, under the colonnade, are all elevated upon pedestals, and will be those of the glorious signers of the Declaration of Independence.

- “Ascending the portico outside to the terrace level a lofty vomitoria (door way) 30 feet high leads into the cella (rotundo gallery) 50 feet wide, 500 feet in circumference and 60 feet high, with a colossal pillar in the centre 70 feet in diameter, around which the gallery sweeps. This pillar forms the foundation of the obelisk column above.

- “Both sides of the gallery are divided into spaces by pilasters, elevated on a continued zocle or base 5 feet high, forming an order with its entablature 40 feet high, crowned by a vaulted ceiling 20 feet high, divided by radiating archevaults, corresponding with the relative positions of the opposing pilasters, and enclosing deep sunken coffers enriched with paintings.

- “The spaces between the pilasters are sunk into niches for the reception of the statues of the fathers of the Revolution, contemporary with the immortal Washington; over which are large tablets to receive the National Paintings commemorative of the battle and other scenes of that memorable period. Opposite to the entrance of this gallery, at the extremity of the great circular wall, is the grand niche for the reception of the statue of the‘'Father of his Country’—elevated on its appropriate pedestal, and designated as principal in the group by its colossal proportions.

- “This spacious Gallery and Rotunda, which properly may be denominated the ‘National Pantheon,’ is lighted in four grand divisions from above, and by its circular form presents each subject decorating it walls in an interesting point of view and with proper effect, as the curiosity is kept up every moment, from the whole room not being presented to the eye at one glance, as in the case of a straight gallery.

- “Entering the centre pier through an arched way, you pass into a spacious circular area, and ascend with an easy grade, by a railway, to the grand terrace, 75 feet above the base of the Monument. This terrace is 700 feet in circumference, 180 feet wide, enclosed by a colonnaded balustrade, 15 feet high with its base and capping. The circuit of this grand terrace is studded with small temple-formed structures, constituting the cupolas of the lanterns, lighting the Pantheon gallery below; by means of these little temples, from a gallery within, a bird’s eye view is had of the statues, &c., below.

- “Through the base of the great circle of the balustrade are four apertures at the four cardinal points, leading outside of the balustrade, upon the top of the main cornice, where a gallery 6 feet wide and 750 feet in circumference encircles the whole, enclosed by an ornamental guard, forming the crowning member on the top of the tholus of the main cornice of the grand colonnade. Within the thickness of this wall, staircases descend to a lower gallery over the plafond of the proanos of the colonnade lighted from above. This gallery, which extends all round the colonnade, is 20 feet wide—divided into rooms for the records of the monument, works of art, or studios for artists engaged in the service of the Monument. Two other ways communicate with this gallery from below.

- “In the centre of the grand terrace above described, rises the lofty obelisk shaft of the Monument, 50 feet square at the base, and 500 feet high, diminishing as it rises to its apex, where it is 40 feet square; at the foot of this shaft and on each face project four massive zocles 25 feet high, supporting so many colossal symbolic tripods of victory 20 feet high, surmounted by fascial columns with their symbols of authority. These zocle faces are embellished with inscriptions, which are continued around the entire base of the shaft, and occupy the surface of that part of the shaft between the tripods. On each face of the shaft above this is sculptured the four leading events in General Washington’s eventful career, in basso relievo, and above this the shaft is perfectly plain to within 50 feet of its summit, where a simple star is placed, emblematic of the glory which the name of WASHINGTON has attained.

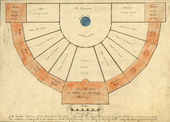

- “To ascend to the summit of the column, the same facilities as below are provided within the shaft, by an easy graded gallery, which may be traversed by a railway, terminating in a circular observatory 20 feet in diameter, around which at the top is a look-out gallery, which opens a prospect all around the horizon.” [Fig. 3]

- Mills, Robert, c. 1841, in a letter to Robert Dale Owen, describing the proposed Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC (Scott, ed., 1990: n.p.)[15]

- “Three spacious avenues (of the city) center within these grounds, which at some future day when improved will form three interesting vistas.”

- Mills, Robert, February 23?, 1841, in a letter to Joel R. Poinsett, describing his design for the National Mall, Washington, DC (Scott, ed., 1990: n.p.)[15]

- “Agreeably to your requisition to prepare a plan of improvement to that part of the Mall lying between 7th and 12th Street West for a botanic garden . . . I have the honor to submit the following Report. . . .

- “Drawing No. 1 presents a general plan of the entire Mall, including that annexed to the President’s house, with the particular improvement proposed of that part intended for the Institution and its objects. . . .[Fig. 4]

- “The relative position of the Capitol, President’s House, and other public buildings are laid down, as also the position of the proposed buildings for the Institution; the adjacent streets and avenues are also shown, with the line of the Canal which courses through the City, at the foot of the Capitol hill to the Eastern Branch near the Navy Yard, thus making of the south western section, a complete island. . . .

- “The principle upon which this plan is founded is two fold, one is to provide suitable space for a Botanic garden, the other to provide locations for subjects allied to agriculture, the propagation of useful and ornamental trees native and foreign, the provision of sites for the erection of suitable buildings to accommodate the various subjects to be lectured on and taught in the Institution. . . .

- “The Botanic garden is laid out in the centre fronting and opening to the south. On each side of this the grounds are laid out in serpentine walks and in picturesque divisions forming plats for grouping the various trees to be introduced and creating shady walks for those visiting the establishments. . . . [Fig. 5]

- “A range of trees is proposed to surround three sides of the square which is intended to be laid open by an iron or other railing, the north side to be enclosed with a high brick wall to serve as a shelter and to secure the various hot houses and other buildings of inferior character.”

- “The main building for the Institution is located about 300 feet south of the wall fronting the Botanic garden, from which it is separated by a circular road, in the centre of which is a fountain of water from the basin of which pipes are led underground thro’ the walks of the garden, for irrigating the same at pleasure, the fountains may be supplied from the canal flowing near the north wall of inclosure. . . . [Fig. 6]

- “By means of Groups and vistas of trees, picturesque views may be obtained of the various buildings and other such objects as may be of a monumental character and thus there would be an attraction produced which would draw many of our citizens and strangers to partake of the pleasure of promenading here.”

Images

Other Resources

Library of Congress Authority File

American National Biography Online

Philadelphia Buildings and Architects

Notes

- ↑ John M. Bryan, ed. Robert Mills, Architect (Washington, DC: American Institute of Architects Press, 1989), 1–8, view on Zotero; John M. Bryan, Robert Mills: America’s First Architect (Princeton, NJ: Princeton Architectural Press, 2001), 6–35, view on Zotero; Rhodri Windsor Liscombe, Altogether American : Robert Mills, Architect and Engineer, 1781–1855 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 3–30, view on Zotero.

- ↑ William D. Hoyt Jr., “Robert Mills and the Washington Monument in Baltimore [Part One],” Maryland Historical Magazine 34 (1939): 153, view on Zotero; J. Jefferson Miller, “The Designs for the Washington Monument in Baltimore, Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 23, no. 1 (March 1964): 23, view on Zotero; Bryan 2001, 112, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Pamela Scott, “Robert Mills and American Monuments,” in Robert Mills, Architect, ed. John M. Bryan (Washington, DC: American Institute of Architects Press, 1989), 146–54, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Scott 1989, 153–54, view on Zotero; Bryan 2001, 139–42, 201–2, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bryan 2001, 220, view on Zotero; Scott 1989, 157–158 view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bryan 2001, 136, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bryan 2001, 151–154, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Pamela Scott, “‘This Vast Empire’: The Iconography of the Mall, 1791–1848,” in The Mall in Washington, ed. Richard Longstreth, Studies in the History of Art, Center for Advanced Studies in the Visual Arts, Symposium Papers, XIV (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1991), 47, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Therese O’Malley, “‘Your Garden Must Be a Museum to You’: Early American Botanic Gardens,” Huntington Library Quarterly 59, no. 2/3 (1996): 226; see also 222–25, view on Zotero; Scott 1991, 47–50, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Liscombe 1994, 163, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 H. M. Pierce Gallagher, Robert Mills, Architect of the Washington Monument, 1781–1855 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1935), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Hoyt 1939, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Catherine C. Lavoie, Washington Monument, Mount Vernon Place, Historic American Buildings Survey. Baltimore, MD, 2005, 13–14, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Frederick L. Harvey, History of the Washington Monument and Washington National Monument Society (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1903), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Pamela Scott, ed., The Papers of Robert Mills (Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Resources, 1990), view on Zotero.