Difference between revisions of "William Bartram"

m |

|||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

Sometime around 1786 Bartram suffered a compound fracture of his right leg when he fell gathering cypress seeds in the garden, and the injury likely prompted Bartram’s retirement from active physical labor. Under his influence, however, the [[Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery]] became, according to Fry, “an educational center that aided in training a new generation of natural scientists and explorers.”<ref>Fry 2004, 1, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/R9R5T6QS view on Zotero]; Fry 2011, 72, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/JNCISBCU view on Zotero].</ref> Bartram was an important mentor to Benjamin Smith Barton (1766–1815), whom Bartram had met just before Barton left to study medicine at Edinburgh University in 1786.<ref>Fry 2011, 82, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/JNCISBCU view on Zotero]. For more on Bartram’s mentoring of figures such as Barton, Alexander Wilson (1766–1813), James Mease (1771–1846), and Thomas Nuttall (1786–1859), see Elizabeth S.C. Fairhead, “Essential Nature: Bartram’s Garden and Natural History in Philadelphia, 1790–1825” (unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Michigan State University, 2005), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/K4CJG9QS view on Zotero].</ref> After returning to Philadelphia, Barton became the first Professor of Natural History and Botany at the University of Pennsylvania, a position that Bartram apparently declined in 1782.<ref>Meyers 2011, 132, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/DDFDA34C view on Zotero].</ref> Barton regularly brought his students to study specimens in [[Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery|Bartram’s garden]], and Bartram produced many natural history drawings for Barton, including a set of drawings to illustrate Linnaean botanical taxonomy that were engraved and published in Barton’s ''Elements of Botany'' (Philadelphia, 1803), the first botany text published in the United States.<ref>Meyers 1986, 120, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/525SSTJI view on Zotero]. Fry suggests that these drawings may have been payment for the education of James Howell Bartram (1783–1818), John Bartram, Jr.’s youngest child. Fry 2011, 83, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/JNCISBCU view on Zotero].</ref> | Sometime around 1786 Bartram suffered a compound fracture of his right leg when he fell gathering cypress seeds in the garden, and the injury likely prompted Bartram’s retirement from active physical labor. Under his influence, however, the [[Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery]] became, according to Fry, “an educational center that aided in training a new generation of natural scientists and explorers.”<ref>Fry 2004, 1, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/R9R5T6QS view on Zotero]; Fry 2011, 72, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/JNCISBCU view on Zotero].</ref> Bartram was an important mentor to Benjamin Smith Barton (1766–1815), whom Bartram had met just before Barton left to study medicine at Edinburgh University in 1786.<ref>Fry 2011, 82, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/JNCISBCU view on Zotero]. For more on Bartram’s mentoring of figures such as Barton, Alexander Wilson (1766–1813), James Mease (1771–1846), and Thomas Nuttall (1786–1859), see Elizabeth S.C. Fairhead, “Essential Nature: Bartram’s Garden and Natural History in Philadelphia, 1790–1825” (unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Michigan State University, 2005), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/K4CJG9QS view on Zotero].</ref> After returning to Philadelphia, Barton became the first Professor of Natural History and Botany at the University of Pennsylvania, a position that Bartram apparently declined in 1782.<ref>Meyers 2011, 132, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/DDFDA34C view on Zotero].</ref> Barton regularly brought his students to study specimens in [[Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery|Bartram’s garden]], and Bartram produced many natural history drawings for Barton, including a set of drawings to illustrate Linnaean botanical taxonomy that were engraved and published in Barton’s ''Elements of Botany'' (Philadelphia, 1803), the first botany text published in the United States.<ref>Meyers 1986, 120, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/525SSTJI view on Zotero]. Fry suggests that these drawings may have been payment for the education of James Howell Bartram (1783–1818), John Bartram, Jr.’s youngest child. Fry 2011, 83, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/JNCISBCU view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| − | Bartram maintained an active correspondence with [[Thomas Jefferson]] (1743–1826) and sent the former U.S. President boxes of seeds to plant at [[Monticello]].<ref>On October 29, 1808, for example, Bartram writes to Jefferson that he is sending him a catalogue of the collection at Bartram’s Garden as well as a packet of seeds of ''Mimosa julibrescens'', a flowering tree native to Persia and Armenia. Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/99-01-02-8979. For all of Bartram's known correspondence and unpublished writings, see Thomas Hallock and Nancy E. Hoffmann, eds., ''William Bartram: The Search for Nature's Design: Selected Art, Letters & Unpublished Writings'' (Athens and London: The University of Georgia Press, 2010), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/MXWPBPH7 view on Zotero].</ref> He also wrote to [[Thomas Jefferson|Jefferson]] in 1806 to decline [[Thomas Jefferson|Jefferson's]] invitation to document the flora and fauna discovered during an expedition to the Red River, “on account of [his] advanced Age & consequent infirmities (being towards 70 Years of Age) And [his] Eyesight declining dayly | + | Bartram maintained an active correspondence with [[Thomas Jefferson]] (1743–1826) and sent the former U.S. President boxes of seeds to plant at [[Monticello]].<ref>On October 29, 1808, for example, Bartram writes to Jefferson that he is sending him a catalogue of the collection at Bartram’s Garden as well as a packet of seeds of ''Mimosa julibrescens'', a flowering tree native to Persia and Armenia. Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/99-01-02-8979. For all of Bartram's known correspondence and unpublished writings, see Thomas Hallock and Nancy E. Hoffmann, eds., ''William Bartram: The Search for Nature's Design: Selected Art, Letters & Unpublished Writings'' (Athens and London: The University of Georgia Press, 2010), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/MXWPBPH7 view on Zotero].</ref> He also wrote to [[Thomas Jefferson|Jefferson]] in 1806 to decline [[Thomas Jefferson|Jefferson's]] invitation to document the flora and fauna discovered during an expedition to the Red River, “on account of [his] advanced Age & consequent infirmities (being towards 70 Years of Age) And [his] Eyesight declining dayly.”<ref>Letter from William Bartram to Thomas Jefferson, February 6, 1806. Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/99-01-02-3187.</ref> Bartram died at home in 1823 at the age of eighty-four, and his niece, Ann Bartram Carr (1779–1858)—who, together with her husband Colonel Robert Carr (1778–1866), had run the garden since 1812—continued to operate the commercial nursery after her uncle’s death. |

--''Lacey Baradel'' | --''Lacey Baradel'' | ||

Revision as of 15:43, January 22, 2018

William Bartram (April 9, 1739–July 22, 1823), an artist-naturalist and author, was son of John Bartram (1699–1777). In 1773 Bartram embarked on a four-year collecting trip to the American Southeast and published an account of his travels in 1791 that became a classic text in the history of American science and literature. Bartram helped run the Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the most important botanic garden of the colonial and early national period.

History

The son of the Pennsylvania Quaker naturalist John Bartram (1699–1777) and his second wife, Ann Mendenhall (1703–1789), William Bartram showed an early interest in botanical pursuits. As a teenager, William accompanied his father on collecting expeditions and made drawings of North American plants that his father sent to colleagues in England and Europe. William’s drawings were greatly admired by contemporaries and were thought by many to rival illustrations produced by well-established British artists Georg Dionysius Ehret (1708–1770) and George Edwards (1694–1773).[1] Despite the praise William received for his drawing abilities, John Bartram worried about the lack of patronage for North American naturalists, writing, “Botany & drawing are his darling delight. I wish he could get A handsom [sic] livelihood by it.”[2] Taking a pragmatic approach to his son’s future, John Bartram apprenticed young William to Captain James Childs, a Philadelphia merchant, from approximately 1756 until 1760, although William continued to assist his father throughout this period and is even believed to have created in 1758 the only known eighteenth-century illustration of the Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery at Kingsessing near Philadelphia [Fig. 1].

In the fall of 1765 William Bartram accompanied his father to the English colony of East Florida. As they approached the Altamaha River near Fort Barrington, Georgia, the Bartrams discovered a plant that would later be named Franklinia alatamaha [Fig. 2], after Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790). William Bartram returned to the spot during the summer of 1776 and gathered seeds from the shrub, which he brought back to the Bartram family’s garden. The shrub was extremely rare, and Bartram later recalled, “We never saw it grow in any other place, nor have I ever seen it growing wild, in all my travels, from Philadelphia to Point Coupe, on the banks of the Mississippi, which must be allowed a very singular and unaccountable circumstance; at this place there are two or three acres of ground where it grows plentifully.” The plant flowered in Bartram’s garden in August 1781 and, two years later, Bartram prepared a detailed description and botanical drawing of the specimen for the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus, Jr. (1741–1783) ().[3]

With money provided by his father, Bartram purchased five hundred acres of land on the St. Johns River in Florida as well as six enslaved people to work the plantation, but the venture failed within a year.[4] Several years later, under the patronage of the English Quaker physician Dr. John Fothergill (1712–1780), Bartram set out on a nearly four-year collecting expedition to the American Southeast, which took him from Philadelphia back to Florida and as far west as the Mississippi.[5] In 1791 Bartram published an account of his expedition entitled Travels through North and South Carolina, Georgia, East and West Florida, the Cherokee Country, the Extensive Territories of the Muscogulges or Creek Confederacy, and the Country of the Chactaws, which one scholar has described as “a travel journal, a naturalist’s notebooks, a moral and religious effusion, an ethnographic essay, and a polemic on behalf of the cultural institutions and rights of American Indians."[6] The book reveals Bartram’s interest in the aesthetics of the sublime. Whereas John Bartram had approached the study of nature through “scientific investigations...based on empirical observations,” according to Margaret Pritchard, William Bartram relied on his imagination in order to experience the vastness and even terror of the natural world, “view[ing] nature as a series of unified relationships” rather than isolated specimens.[7] Bartram’s Travels received mixed response from critics. Published nearly fifteen years after his expedition, the book seemed out of date by the time it was published; many of Bartram’s discoveries had already been published by other scientists. Meyers has argued that although the book would “become one of the classic early texts in the genre of Romantic travel writing” and was praised by Romantic authors and poets in America and Europe, it received less support from the popular press because of “the unfamiliar tone of its impassioned descriptions of the natural world.”[8]

John Bartram retired in the spring of 1771, and his son John Bartram Jr. (1743–1812) took over the family garden and nursery business. When John Bartram died in 1777, he left the Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery to his son John.[9] William Bartram assisted his younger brother, although the exact nature of their business relationship remains unknown. According to Joel T. Fry, it appears that John made annual collecting trips and William “tended to the written and academic side of the partnership.” Both brothers apparently boxed seeds and plants for shipment to England and Europe, and William continued to make botanical drawings of new specimens. In 1783 William Bartram prepared a broadside list of the plant collection at the Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery for publication in Philadelphia and, with the help of Benjamin Franklin, in Paris. The catalogue includes 218 plant species, most of which had been collected and planted by the elder John Bartram before his death. However, the list also includes “Three Undescript [sic] Shrubs, lately from Florida”: Philadelphus (Philadelphus inodorus), Alatamaha (Franklinia alatamaha), and Gardenia (Fothergilla gardenii), all species that William Bartram introduced to the garden after his travels to the Southeast.[10]

Sometime around 1786 Bartram suffered a compound fracture of his right leg when he fell gathering cypress seeds in the garden, and the injury likely prompted Bartram’s retirement from active physical labor. Under his influence, however, the Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery became, according to Fry, “an educational center that aided in training a new generation of natural scientists and explorers.”[11] Bartram was an important mentor to Benjamin Smith Barton (1766–1815), whom Bartram had met just before Barton left to study medicine at Edinburgh University in 1786.[12] After returning to Philadelphia, Barton became the first Professor of Natural History and Botany at the University of Pennsylvania, a position that Bartram apparently declined in 1782.[13] Barton regularly brought his students to study specimens in Bartram’s garden, and Bartram produced many natural history drawings for Barton, including a set of drawings to illustrate Linnaean botanical taxonomy that were engraved and published in Barton’s Elements of Botany (Philadelphia, 1803), the first botany text published in the United States.[14]

Bartram maintained an active correspondence with Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826) and sent the former U.S. President boxes of seeds to plant at Monticello.[15] He also wrote to Jefferson in 1806 to decline Jefferson's invitation to document the flora and fauna discovered during an expedition to the Red River, “on account of [his] advanced Age & consequent infirmities (being towards 70 Years of Age) And [his] Eyesight declining dayly.”[16] Bartram died at home in 1823 at the age of eighty-four, and his niece, Ann Bartram Carr (1779–1858)—who, together with her husband Colonel Robert Carr (1778–1866), had run the garden since 1812—continued to operate the commercial nursery after her uncle’s death.

--Lacey Baradel

Texts

- Bartram, John, March 14, 1756, in a letter to Alexander Garden (Berkeley and Berkely, 1969: 86)[17]

- “I am obliged to thee for thy kindness to my son William. He longs to be with thee; but it is more for the sake of Botany, than Physic or Surgery, neither of which he seems to have any delight in. I have several books of both but can’t persuade him to read a page in either. Botany and drawing are his delight.”

- Bartram, William and John Bartram, Jr., August 16, 1783, in a letter to Carl Linnaeus, Jr. (quoted in Fry 2011: 74)[18] back up to history

- "This very beautiful Shrub I discovered growing in Florida about 5 years ago & brought the ripe seed to Philadelphia, from these seed grew 5 plants, two of which were taken to France by Monsr. Gerard Emasedor to these States & were to be planted in the Royal garden at Versailes. Two plants are here now finely in Flower in the open ground, & perfectly resist our hardest Winters."

- Marshall, Humphry, December 5, 1785, in a letter to Benjamin Franklin (Darlington 1849: 522–523)[19]

- "I had it in contemplation to mention to thee for thy approbation, or sentiments thereon, a proposal that I had made, last winter, to my cousin, WM. BARTRAM, and nephew, Dr. MOSES MARSHALL, of taking a tour, mostly through the western parts of our United States, in order to make observations, &c, upon the Natural productions of those regions; with a variety of which, hitherto unnoticed, or but imperfectly described, we have reason to believe they abound; which, on consideration, they at that time seemed willing to undertake, and I conceive would be so still, provided they should meet with proper encouragement and support for such a journey; which they judge would be attended with considerable expense, for the transportation of their collections, &c, and for their subsistence during a period of fifteen or eighteen months, or more, which would at least be necessary for the completion of the numerous observations, and objects they would have to make remarks on, and collect. Should such proposals be properly encouraged, I apprehend they would engage to set out early in the spring, and throughout their journey make diligent search and strict observation upon everything within the province of a naturalist; but more especially upon Botany, for the exercise of which there appears, in such a journey, a most extensive field; for, from accounts of our western territories, they are said to abound with varieties of strange trees, shrubs, and plants, no doubt applicable to many valuable purposes in arts or manufactures, and to be replete with various species of earths, stones, salts, inflammable minerals, and metals (the many uses of obtaining a knowledge of which is sufficiently obvious); remarks, experiments, &c, upon every of which they propose making; as also to make collections, and preserve specimens, of everything that may enrich useful science, or amuse the curious naturalist; to the conducement of which, they would willingly receive and observe any reasonable instructions that might facilitate their discoveries, or direct their researches.

- "I have taken the freedom to mention these proposals to thee knowing that thou was always ready and willing to promote any useful knowledge and science, for the use of mankind ; and if, on consideration of the premises, thou should approve thereof, thou may communicate them to the members of the Philosophical Society, or any other set of gentlemen, that would be willing or likely to encourage such an undertaking. Perhaps Congress, or some of the members, might promote their going out with the surveyors, when they lay out the several new states.

- "I have ordered my nephew, the Doctor, to present thee with one of my Catalogues of the Forest Trees of our Thirteen United States; which I hope thou'll accept of, for thy perusal."

- Cutler, Rev. Manasseh, July 14, 1787, describing the Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery and his encounter with members of the Bartram family—probably William and his brother John Bartram, Jr. (1888: 1:272-74)[20]

- "We crossed the Schuylkill, at what is called the lower ferry, over the floating bridge, to Gray's tavern, and, in about two miles, came to Mr. Bartram's seat. We alighted from our carriages, and found our company were : Mr. [Caleb] Strong, Governor [Alexander] Martin, Mr. [George] Mason and son, Mr. [Hugh] Williamson, Mr. [James] Madison, Mr. [John] Rutledge, and Mr. [Alexander] Hamilton, all members of Convention, Mr. Vaughan, and Dr. [Gerardus] Clarkson and son. Mr. Bartram lives in an ancient Fabric, built with stone, and very large, which was the seat of his father. His house is on an eminence fronting to the Schuylkill, and his garden is on the declivity of the hill between his house and the river. We found him, with another man, hoeing in his garden, in a short jacket and trowsers, and without shoes or stockings. He at first stared at us, and seemed to be somewhat embarrassed at seeing so large and gay a company so early in the morning. Dr. Clarkson was the only person he knew, who introduced me to him, and informed him that I wished to converse with him on botanical subjects, and, as I lived in one of the Northern States, would probably inform him of trees and plants which he had not yet in his collection; that the other gentlemen wished for the pleasure of a walk in his garden. I instantly entered on the subject of botany with as much familiarity as possible, and inquired after some rare plants which I had heard that he had. He presently got rid of his embarrassment, and soon became very sociable, which was more than I expected, from the character I had heard of the man. I found him to be a practical botanist, though he seemed to understand little of the theory. We ranged the several alleys, and he gave me the generic and specific names, place of growth, properties, etc., so far as he knew them. This is a very ancient garden, and the collection is large indeed, but is made principally from the Middle and Southern States. It is finely situated, as it partakes of every kind of soil, has a fine stream of water, and an artificial pond, where he has a good collection of aquatic plants. There is no situation in which plants or trees are found but that they may be propagated here in one that is similar. But every thing is very badly arranged, for they are neither placed ornamentally nor botanically, but seem to be jumbled together in heaps. The other gentlemen were very free and sociable with him, particularly Governor Martin, who has a smattering of botany and a fine taste for natural history. There are in this garden some very large trees that are exotic, particularly an English oak, which he assured me was the only one in America. He had the Pawpaw tree, or Custard apple. It is small, though it bears fruit ; but the fruit is very small. He has also a large number of aromatics, some of them trees, and some plants. One plant I thought equal to cinnamon. The Franklin tree is very curious. It has been found only on one particular spot in Georgia.... From the house is a walk to the river, between two rows of large, lofty trees, all of different kinds, at the bottom of which is a summer-house on the bank, which here is a ledge of rocks, and so situated as to be convenient for fishing in the river, where a plenty of several kinds of fish may be caught. Mr. Bartram showed us several natural curiosities in the place where he keeps his seeds; they were principally fossils. He appeared fond of exchanging a number of his trees and plants for those which are peculiar to the Northern States. We proposed a correspondence, by which we could more minutely describe the productions peculiar to the Southern and Northern States.

- "About nine, we took our leave of Mr. Bartram, who appeared to be well pleased with his visitors, and returned to Gray's tavern, where we breakfasted."

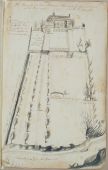

- Bartram, William, 1789, describing settlements of the Muscogulge and Cherokee Indians (1853: 51–53)[21]

- “PLAN OF THE ANCIENT CHUNKY-YARD.

- “The subjoined plan . . . will illustrate the form and character of these yards.

- “A, the great area, surrounded by terraces or banks.

- “B, a circular eminence, at one end of the yard, commonly nine or ten feet higher than the ground round about. Upon this mound stands the great Rotunda, Hot House, or Winter Council House, of the present Creeks. It was probably designed and used by the ancients who constructed it, for the same purpose.

- “C, a square terrace or eminence, about the same height with the circular one just described, occupying a position at the other end of the yard. Upon this stands the Public Square.

- “The banks inclosing the yard are indicated by the letters b, b, b, b; c indicate the “Chunk-Pole,” and d, d, the “Slave-Posts.”

- “Sometimes the square, instead of being open at the ends, as shown in the plan, is closed upon all sides by the banks. In the lately built, or new Creek towns, they do not raise a mound for the foundation of their Rotundas or Public Squares. The yard, however, is retained, and the public buildings occupy nearly the same position in respect to it. They also retain the central obelisk and the slave-posts.” [Fig. 3]

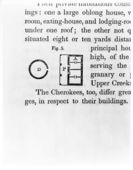

- Bartram, William, 1789, describing Indian settlements in North Carolina, Georgia, and Florida (1853: 57–58)[21]

- “In the Cherokee country, all over Carolina, and the Northern and Eastern parts of Georgia, wherever the ruins of ancient Indian towns appear, we see always beside these remains one vast, conical-pointed mound. To mounds of the kind I refer when I speak of pyramidal mounds. To the south and west of the Altamaha, I observed none of these in any part of the Muscogulge country, but always flat or square structures. The vast mounds upon the St. John’s, Alachua, and Musquito rivers, differ from those amongst the Cherokee with respect to their adjuncts and appendages, particularly in respect to the great highway or avenue, sunk below the common level of the earth, extending from them, and terminating either in a vast savanna or natural plain, or an artificial pond or lake. A remarkable example occurs at Mount Royal, from whence opens a glorious view of Lake George and its environs.

- “Fig. 6 is a perspective plan of this great mound and its avenues, the latter leading off to an expansive savanna or natural meadow. A, the mound, about forty feet in perpendicular height; B, the highway leading from the mound in a straight line to the pond C, about a half a mile distant. . . . The sketch of the mound also illustrates the character of the mounds in the Cherokee country; but the last have not the highway or avenue, and are always accompanied by vast square terraces, placed upon one side or the other. On the other hand, we never see the square terraces accompanying the high mounds of East Florida.” [Fig. 4]

- Bartram, William, 1791, describing the area north of Wrightsborough, Ga. (1928: 56–57)[22]

- “many very magnificent monuments of the power and industry of the ancient inhabitants of these lands are visible. I observed a stupendous conical pyramid, or artificial mount of earth, vast tetragon terraces, and a large sunken area, of a cubical form, encompassed with banks of earth; and certain traces of a larger Indian town, the work of a powerful nation, whose period of grandeur perhaps long preceded the discovery of this continent. . . .

- “old Indian settlements, now deserted and overgrown with forests. These are always on or near the banks of rivers, or great swamps, the artificial mounts and terraces elevating them above the surrounding groves.”

- Bartram, William, 1791, describing St. Simon’s Island, Ga. (1928: 72–73)[22]

- “This delightful habitation was situated in the midst of a spacious grove of Live Oaks and Palms, near the strand of the bay, commanding a view of the inlet. A cool area surrounded the low but convenient buildings, from whence, through the groves, was a spacious avenue into the island, terminated by a large savanna. . . .

- “Our rural table was spread under the shadow of Oaks, Palms, and Sweet Bays, fanned by the lively salubrious breezes wafted from the spicy groves. Our music was the responsive love-lays of the painted nonpareil, and the alert and gay mock-bird; whilst the brilliant humming-bird darted through the flowery groves, suspended in air, and drank nectar from the flowers of the yellow Jasmine, Lonicera, Andromeda, and sweet Azalea.”

- Bartram, William, 1791, describing Marshall Plantation, on the San Juan River, Fla. (1928: 84)[22]

- “In the afternoon, the most sultry time of the day, we retired to the fragrant shades of an orange grove. The house was situated on an eminence, about one hundred and fifty yards from the river. On the right hand was the orangery, consisting of many hundred trees, natives of the place, and left standing, when the ground about it was cleared. These trees were large, flourishing, and in perfect bloom, and loaded with their ripe golden fruit. On the other side was a spacious garden, occupying a regular slope of ground down to the water; and a pleasant lawn lay between.”

- Bartram, William, 1791, describing an Indian village in Fla. (1928: 96)[22]

- “There was a large Orange grove at the upper end of their village; the trees were large, carefully pruned, and the ground under them clean, open, and airy.”

- Bartram, William, 1791, describing Lake George, Ga. (1928: 101, 104)[22]

- “From this place we enjoyed a most enchanting prospect of the great Lake George, through a grand avenue, if I may so term this narrow reach of the river, which widens gradually for about two miles, towards its entrance into the lake, so as to elude the exact rules of perspective, and appears of an equal width. . . .

- “On the site of this ancient town, stands a very pompous Indian mount, or conical pyramid of earth, from which runs in a straight line a grand avenue or Indian highway, through a magnificent grove of magnolias, live oaks, palms, and orange trees, terminating at the verge of a large green level savanna.”

- Bartram, William, 1791, describing Lake George, Ga., and settlements of the Muscogulge and Cherokee Indians (1928: 101–102, 407)[22]

- “At about fifty yards distance from the landing place, stands a magnificent Indian mount. . . . But what greatly contributed towards completing the magnificence of the scene, was a noble Indian highway, which led from the great mount, on a straight line, three quarters of a mile, first through a point or wing of the orange grove, and continuing thence through an awful forest of live oaks, it was terminated by palms and laurel magnolias, on the verge of an oblong artificial lake, which was on the edge of an extensive green level savanna. . . .The glittering water pond played on the sight, through the dark grove, like a brilliant diamond, on the bosom of the illumined savanna, bordered with various flowery shrubs and plants. . . .

- “From the river St. Juans, Southerly, to the point of the peninsula of Florida, are to be seen high pyramidal mounts with spacious and extensive avenues, leading from them out of the town, to an artificial lake or pond of water; these were evidently designed in part for ornament or monuments of magnificence, to perpetuate the power and grandeur of the nation.”

- Bartram, William, 1791, describing an Indian town in Cuscowilla, Ga. (1928: 167–168)[22]

- “Upon our arrival we repaired to the public square or council-house, where the chiefs and senators were already convened. . . .

- “The banquet succeeded; the ribs and choicest fat pieces of the bullocks, excellently well barbecued, were brought into the apartment of the public square, constructed and appointed for feasting.”

- Bartram, William, 1791, describing a typical house in Cuscowilla, Ga. (1928: 168–169)[22]

- “The dwelling stands near the middle of a square yard, encompassed by a low bank, formed with the earth taken out of the yard, which is always carefully swept.”

- Bartram, William, 1791, describing an Indian town in Georgia (1928: 169–170)[22]

- “They plant but little here about the town; only a small garden plot at each habitation. . . . Their plantation, which supplies them with the chief of their vegetable provisions . . . lies on the rich prolific lands bordering on the great Alachua savanna, about two miles distance. This plantation is one common enclosure, and is worked and tended by the whole community.”

- Bartram, William, 1791, describing Indian village south of Charlotia (1928: 250–251)[22]

- “We were received and entertained friendlily [sic] by the Indians, the chief of the village conducting us to a grand, airy pavilion in the center of the village. It was four square; a range of pillars or posts on each side supporting a canopy composed of Palmetto leaves, woven or thatched together, which shaded a level platform in the center, that was ascended to from each side by two steps or flights, each about twelve inches high, and seven or eight feet in breadth, all covered with carpets or mats, curiously woven, of split canes dyed of various colours. Here being seated or reclining ourselves, after smoaking tobacco, baskets of the choicest fruits were brought and set before us.”

- Bartram, William, 1791, describing settlements of the Muscogulge and Cherokee Indians (1928: 406)[22]

- “The pyramidal hills or artificial mounts, and highways, or avenues, leading from them to artificial lakes or ponds, vast tetragon terraces, chunk yards,* and obelisks or pillars of wood, are the only monuments of labour, ingenuity and magnificence that I have seen worthy of notice, or remark.

- "* Chunk yard, a term given by white traders, to the oblong four square yards, adjoining the high mounts and rotundas of the modern Indians.—In the centre of these stands the obelisk, and at each corner of the farther end stands a slave post or strong stake, where the captives that are burnt alive are bound.”

- Bartram, William, 1792, describing islands off the coast of Georgia and Florida (1996: 93)[23]

- “These floating islands present a very entertaining prospect; for although we behold an assemblage of the primary productions of nature only, yet the imagination seems to remain in suspense and doubt; as in order to enliven the delusion, and form a most picturesque appearance we see not only flowery plants, clumps of shrubs, old-weather beaten trees, hoary and barbed, with the long moss waving from their snags, but we also see them completely inhabited, and alive, with crocodiles, serpents, frogs, otters, crows, herons, curlews, jackdaws, &c. There seems, in short, nothing wanted but the appearance of a wigwam and a canoe to complete the scene.”

- Niemcewicz, Julian Ursyn, March 24, 1798, journal entry describing the Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery (1965: 52)[24]

- "Straightaway I came upon Bartram, the traveler and poet. He is a man between 50 and 60, small, spare, with a quick-tempered air. In a red vest and leather breeches, he was digging up the ground. Is this the giant, I said to myself, who engaged in such frightful battles with alligators and bears? He seemed to me gentle and upright. A little further on his brother was squatting on the bank of a sort of a stream, his hands completely buried in the mud; he was planting something. His manner was not affable; he improved later; he showed us a few trees and bushes, brought for the most part from Georgia and the Carolinas, and the remainder from the Continent. His interest in botany, added to the profits that he has made from it, has led him to undertake, at times, journeys of 100 miles solely to go into a forest to collect there a plant or a bush. . . . Bartram deals in plants, flowers, bushes, etc.; he sells much to Europe. He is the best botanist in this country."

- Pursh, Frederick, 1814, describing a visit to Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery in 1799 (1814: 1: vi)[25]

- "Near Philadelphia I found the botanic garden of Messrs. John and William Bartram. This is likewise an old establishment, founded under the patronage of the late Dr. Fothergill, by the father of the now living Bartrams. This place, delightfully situated on the banks of the Delaware, is kept up by the present proprietors, and probably will increase under the care of the son of John Bartram, a young gentleman of classical education, and highly attached to the study of botany. Mr. William Bartram, the well known author of “Travels through North and South Carolina,” I found a very intelligent, agreeable, and communicative gentleman; and from him I received considerable information about the plants of that country, particularly respecting the habitats of a number of rare and interesting trees. It is with the liveliest emotions of pleasure I call to mind the happy hours I spent in this worthy man’s company, during the period I lived in his neighbourhood.

Images

Other Resources

Library of Congress Authority File

The Cultural Landscape Foundation

American Philosophical Society

Notes

- ↑ Amy R. W. Meyers, “From Nature and Memory: William Bartram’s Drawings of North American Flora and Fauna,” in Knowing Nature: Art and Science in Philadelphia, 1740–1840, ed. by Amy R. W. Meyers (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2011), 130, view on Zotero; Margaret Pritchard, “A Protracted View: The Relationship between Mapmakers and Naturalists in Recording the Land,” in Knowing Nature, 24, view on Zotero; Charlotte M. Porter, “Philadelphia Story: Florida Gives William Bartram a Second Chance,” The Florida Historical Quarterly 71, no. 3 (January 1993): 310–313, view on Zotero. From January 1752 until July 1755, William Bartram attended the Philadelphia Academy, where he studied French and Latin and may have also received instruction in drawing. Joel T. Fry, “America’s ‘Ancient Garden’: The Bartram Botanic Garden, 1728–1850,” in Knowing Nature, 72, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Letter from John Bartram to Peter Collinson, September 28, 1755; quoted in Fry 2011, 72, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Quoted in Fry 2011, 74, view on Zotero. According to Fry, all existing Franklinia may be descended from William Bartram’s plants. See also Judith Magee, The Art and Science of William Bartram (University Park, Pa.: The Pennsylvania State University Press in association with the Natural History Museum, London, 2007), 64–68, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Fry 2011, 72, view on Zotero; Porter 1993, 315–317, view on Zotero. According to Michael Gaudio, after the American Revolution, “Bartram expressed his opposition to the practice of slavery in an unpublished essay.” Michael Gaudio, “Swallowing the Evidence: William Bartram and the Limits of the Enlightenment,” Winterthur Portfolio 36, no. 1 (Spring 2001): 16, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Pritchard 2011, 24–25, view on Zotero; Fry 2011, 72, view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Bartram, Travels through North and South Carolina, Georgia, East and West Florida, the Cherokee Country, the Extensive Territories of the Muscogulges or Creek Confederacy, and the Country of the Chactaws: Containing an Account of the Soil and Natural Productions of those Regions; together with Observations on the Manners of the Indians (Philadelphia: James and Johnson, 1791), view on Zotero; Douglas Anderson, “Bartram’s Travels and the Politics of Nature,” Early American Literature 25, no. 1 (1990): 3, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Pritchard 2011, 26–27, view on Zotero. For more on Bartram’s notions of “environmental unity,” see Amy R. W. Meyers, “Imposing Order on the Wilderness: Natural History Illustration and Landscape Portrayal,” in Views and Visions: American Landscape before 1830, ed. by Edward J. Nygren and Bruce Robertson (Washington, D.C.: The Corcoran Gallery of Art, 1986), 121, view on Zotero; and Amy R. Weinstein Meyers, “Sketches from the Wilderness: Changing Conceptions of Nature in American Natural History Illustration, 1680–1880 (unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Yale University, 1985), especially pages 152–258, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Meyers 2011, 132, view on Zotero. Subsequent editions were published in London in 1792 and 1794, Berlin and Vienna in 1793, Haarlem between 1794 and 1797, Amsterdam in 1797, and Paris in 1799 and 1801. Fry 2004, 45, view on Zotero. For more on the influence Bartram’s Travels had on Romantic writing, see Ashton Nichols, “Roaring Alligators and Burning Tygers: Poetry and Science from William Bartram to Charles Darwin," Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 149, no. 3 (September 2005): 305–308, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Fry 2011, 72, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Fry 2011, 72–73, view on Zotero. According to Fry, the 1783 Catalogue is “the first botanic list of North American plants to be printed in America, and is also one of the earliest known nursery catalogues from the United States.” Fry 2004, 47, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Fry 2004, 1, view on Zotero; Fry 2011, 72, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Fry 2011, 82, view on Zotero. For more on Bartram’s mentoring of figures such as Barton, Alexander Wilson (1766–1813), James Mease (1771–1846), and Thomas Nuttall (1786–1859), see Elizabeth S.C. Fairhead, “Essential Nature: Bartram’s Garden and Natural History in Philadelphia, 1790–1825” (unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Michigan State University, 2005), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Meyers 2011, 132, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Meyers 1986, 120, view on Zotero. Fry suggests that these drawings may have been payment for the education of James Howell Bartram (1783–1818), John Bartram, Jr.’s youngest child. Fry 2011, 83, view on Zotero.

- ↑ On October 29, 1808, for example, Bartram writes to Jefferson that he is sending him a catalogue of the collection at Bartram’s Garden as well as a packet of seeds of Mimosa julibrescens, a flowering tree native to Persia and Armenia. Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/99-01-02-8979. For all of Bartram's known correspondence and unpublished writings, see Thomas Hallock and Nancy E. Hoffmann, eds., William Bartram: The Search for Nature's Design: Selected Art, Letters & Unpublished Writings (Athens and London: The University of Georgia Press, 2010), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Letter from William Bartram to Thomas Jefferson, February 6, 1806. Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/99-01-02-3187.

- ↑ Edmund Berkeley and Dorothy Smith Berkeley, Dr. Alexander Garden of Charles Town (Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 1969), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Fry 2011, view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Darlington, Memorials of John Bartram and Humphry Marshall: With Notices of Their Botanical Contemporaries (Philadelphia: Lindsay & Blakiston, 1849), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Manasseh Cutler, Life, Journals and Correspondence of Rev. Manasseh Cutler, L.L.D., ed. by William Parker Cutler and Julia Perkin Cutler, vol. 1 (Cincinnati: Robert Clarke & Co., 1888), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 William Bartram, "Observations on the Creek and Cherokee Indians, 1789, with Prefatory and Supplementary Notes by E.G. Squier," Transactions of the American Ethnological Society, 3 (1853), 1–81, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 22.00 22.01 22.02 22.03 22.04 22.05 22.06 22.07 22.08 22.09 22.10 William Bartram, Travels through North and South Carolina, Georgia, East and West Florida, ed. by Mark Van Doren (New York: Dover, 1928), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Bartram, Travels, and Other Writings (New York: Library of America, 1996), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz, Under Their Vine and Fig Tree: Travels through America in 1797–99, 1805, with Some Further Account of Life in New Jersey, ed. & trans. by Metchie J. E. Budka, Collections of The New Jersey Historical Society at Newark (Elizabeth, NJ: The Grassmann Publishing Company, 1965), xiv, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Frederick Pursh, Flora Americae Septentrionalis; Or, a Systematic Arrangement and Description of the Plants of North America, 2 vols (London: White, Cochrane, & Co., 1814), view on Zotero.