Difference between revisions of "Temple"

V-Federici (talk | contribs) m (→Inscribed) |

V-Federici (talk | contribs) m (→Attributed) |

||

| Line 295: | Line 295: | ||

Image:0009_detail2.jpg|[[Charles Willson Peale]], Letter to Angelica Peale describing his garden at [[Belfield]] [detail], November 22, 1815. | Image:0009_detail2.jpg|[[Charles Willson Peale]], Letter to Angelica Peale describing his garden at [[Belfield]] [detail], November 22, 1815. | ||

| − | Image:0044.jpg|[[Charles Willson Peale]], ''View of the garden at [[Belfield]]'', 1816. | + | Image:0044.jpg|[[Charles Willson Peale]], ''[[View]] of the garden at [[Belfield]]'', 1816. |

| + | |||

| + | Image:0044_detail4.jpg| [[Charles Willson Peale]], ''[[View]] of the garden at [[Belfield]]'' [detail], 1816. | ||

Image:0646.jpg|Anonymous, “Montpelier, Va., the Seat of the late James Madison,” 1835. | Image:0646.jpg|Anonymous, “Montpelier, Va., the Seat of the late James Madison,” 1835. | ||

Revision as of 16:23, March 29, 2021

See also: Hermitage, Icehouse, Pavilion, Summerhouse.

History

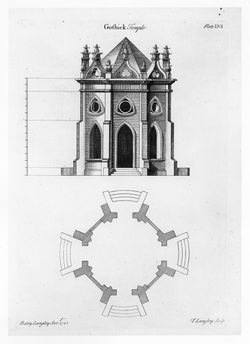

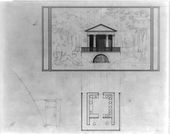

In architectural history, the term temple was derived from at least two design traditions—the classical and the Chinese. The temple in the American garden was a structure that could assume many stylistic variants and could adapt to a range of scales and locations. To illustrate this point, consider the temple that was dressed in the Chinese style at Belfield in Germantown, Pennsylvania, the Gothic at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, and the Grecian at Monticello. Charles Willson Peale’s Chinese temple at Belfield was intended for meditation and reflection because, he claimed, the Chinese were great philosophers.[1] In the treatise Rural Architecture in the Chinese Taste (1755), William and John Halfpenny illustrated an elaborate temple, replete with Chinese statuary [Fig. 1]. On a more practical level, A. J. Downing showed in his treatise how the application of zigzag wooden latticework could transform a simple temple structure into one “in Chinese taste.” James Gibbs’s Book of Architecture (1728) provided Thomas Jefferson with classical models of temples, while Batty and Thomas Langley’s Gothic Architecture (1747) offered a range of designs in the “Gothick” mode [Fig. 2].

The temple in its classical form became an icon of the American republic. The association of Roman virtue with agriculture resulted from the 18th-century rediscovery of ancient texts by Virgil and Pliny the Younger, who had written about husbandry, villas, and plantations. Early Americans embraced classical republican imagery in the design of their gardens, which reaffirmed the agrarian ideal through the use of ornament and inscription, as well as through the celebration of the farm and garden. At Gray’s Garden in Philadelphia, a “federal” temple was built to celebrate the ratification of the Constitution. The structure was composed of a rotunda in which the interior space was defined by thirteen columns representing the thirteen original colonies. Patriotic interpretations of the classical temple form were also to be found in private gardens. For example, Peale’s Belfield also had a classical temple with thirteen columns, which was surmounted by a bust of George Washington in place of a traditional Roman one.

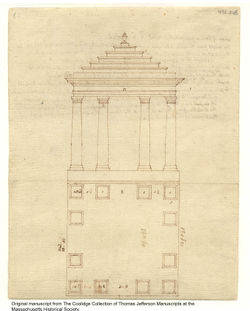

At Grants Hill in Pittsburgh, small temples were built, each in a different order of architecture. Jefferson likewise planned several temples for his plantation at Monticello of varying stylistic forms—Chinese, Gothic, and classical. Some of these designs exemplify Jefferson’s interest in archaeology while others illustrate his highly imaginative recreations of historical styles. Jefferson relied upon his excellent library of architectural treatises for models, and for some projects he copied elements from the Lantern of Demosthenes, the temple at Chiswick by Lord Burlington, and the Chinese pagoda at Kew Gardens. In another instance, he invented a Gothic variant for a design.[2]

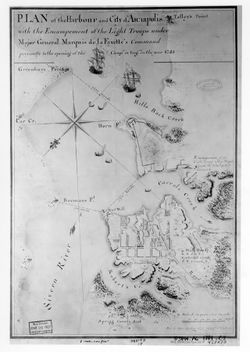

Temples also varied widely in scale. The Temple of Solitude at the Friends Asylum for the Insane, near Frankford, Pennsylvania, was intended, presumably, for one person to occupy alone. Vauxhall Garden in New York, on the other hand, featured another nationally inspired temple, the Grand Temple of Independence, which was an impressive twenty feet in diameter, the same in height, and was crowned by a bust of George Washington. The temple type was at times used either to decorate or to disguise utilitarian structures; examples include the icehouse at Montpelier, the dovecote [Fig. 3] and out-chamber at Monticello [See Fig. 6], and Latrobe’s garden temple [Fig. 4]. As Jefferson instructed, temples often were isolated in the garden, placed on top of mounts, or in woods that were gloomy and evergreen. One such example is an 1804 sketch by Jefferson for the location at Monticello of a temple (or a seat) at the center of a spiral labyrinth [See Fig. 7]. Another example, a “rustic temple,” published in the Horticulturist in 1847, is shown at the edge of the lake at Montgomery Place in Dutchess County, New York [see Fig. 10]. With this type of siting, temples provided a retreat for meditation. In the novel Wieland, or The Transformation, An American Tale (1798), the temple was placed at the top of a rock, far from the house. It was a place of resort and instruction and held a harpsichord and a piece of sculpture.

The term “temple” was often used interchangeably with “pavilion,” “pleasure” or “garden house,” and “summerhouse,” all referring to lightweight structures within the garden or landscape (see Pavilion, Pleasure ground, and Summerhouse). Like them, the temple served as a viewing platform, as a visual punctuation in the garden scene, and as a shelter and resting place within the landscape.

—Therese O’Malley

Texts

Usage

- Sansom, Hannah Callender, June 30, 1762, diary entry describing Belmont, estate of William Peters, near Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Callender 2010: 183)[3]

- “. . . a broad walk of english Cherre trys leads down to the river, the doors of the hous opening opposite admitt a prospect [of] the length of the garden thro’ a broad gravel walk, to a large hansome summer house in a grean. . . we left the garden for a wood cut into Visto’s, in the midst a chinese temple for a summer house. . .”

- Jefferson, Thomas, 1771, describing Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, VA (1944: 25–26)[4]

- “choose out for a Burying place some unfrequented vale in the park, where is, ‘no sound to break the stillness but a brook, that bubbling winds among the weeds; no mark of any human shape that had been there, unless the skeleton of some poor wretch, Who sought that place out to despair and die in.’ let it be among antient [sic] and venerable oaks; intersperse some gloomy evergreens. the area circular, abt. 60 f. diameter, encircled with an untrimmed hedge of cedar, or of stone wall with a holly hedge on it in the form below in the center of it erect a small Gothic temple of antique appearance. appropriate one half to the use of my own family, the other of strangers, servants, etc. erect pedestals with urns, etc., and proper inscriptions. the passage between the walls, 4 f. wide. on the grave of a favorite and faithful servant might be a pyramid erected of the rough rock-stone; the pedestal made plain to receive an inscription. let the exit of the spiral at (a) look on a small and distant part of the blue mountains. in the middle of the temple an altar, the sides of turf, the top of plain stone. very little light, perhaps none at all, save only the feeble ray of an half extinguished lamp. . .

- “a few feet below the spring level the ground 40 or 50 f. sq. let the water fall from the spring in the upper level over a terrace in the form of a cascade. then conduct it along the foot of the terrace to the Western side of the level, where it may fall into a cistern under a temple, from which it may go off by the western border till it falls over another terrace at the Northern or lower side. let the temple be raised 2. f. for the first floor of stone. under this is the cistern, which may be a bath or anything else. the 1st story arches on three sides; the back or western side being close because the hill there comes down, and also to carry up stairs on the outside. the 2d story to have a door on one side, a spacious window in each of the other sides, the rooms each 8. f. cube; with a small table and a couple of chairs. the roof may be Chinese, Grecian, or in the taste of the Lantern of Demosthenes at Athens.” [Fig. 5 and 6]

- Constantia [Judith Sargent Murray], June 24, 1790, “Description of Gray’s Gardens, Pennsylvania” (Massachusetts Magazine 3: 415)[5]

- “At every turn shaded seats are artfully contrived,and the ground abounds with arbours, alcoves, and summer houses, which are handsomely adorned with odoriferous flowers. Among these the little federal temple claims the principal regard. It is the very edifice, that upon the celebration of the ratification of the constitution, was carried in triumphant procession through the streets of this metropolis; and, upon a gentle acclivity,upon the summit of a green mound in fixed, it hath now obtained a basis. It is a Rotunda, its cupola is supported by thirteen pillars handsomely finished; their base, is to receive the cypher of the several states, which they represent, with a star upon every capital, and its top is crowned with the figure of Plenty grasping the cornucopia and other insignia. The ascent to this Temple is easy, and we gain it by the semicircular steps neatly turned, and the view therefrom is truly interesting.”

- Anonymous, August 27, 1795, describing in the Alexandria Gazette a tavern property in Annapolis, MD (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “Indian Queen. FOR SALE, THAT well known Tavern and Stage House. . . The out-buildings are, a coach house, a wash-house, billiard-house, a small office and an excellent temple.”

- Brown, Charles Brockden, 1798, describing the fictional estate of Wieland, near Philadelphia, PA (1798: 9, 24–25) [6]

- “At the distance of three hundred yards from his house, on the top of a rock whose sides were steep, rugged, and encumbered with dwarf cedars and stony asperities, he built what to a common eye would have seemed a summer-house. The eastern verge of this precipice was sixty feet above the river which flowed at its foot. The view before it consisted of a transparent current, fluctuating and rippling in a rocky channel, and bounded by a rising scene of cornfields and orchards. The edifice was slight and airy. It was no more than a circular area, twelve feet in diameter, whose flooring was the rock, cleared of moss and shrubs, and exactly levelled, edged by twelve Tuscan columns, and covered by an undulating dome. My father furnished the dimensions and outlines, but allowed the artist whom he employed to complete the structure on his own plan. It was without seat, table, or ornament of any kind.

- “This was the temple of his Deity. . .

- “[years later] The temple was no longer assigned to its ancient use. From an Italian adventurer, who erroneously imagined that he could find employment for his skill, and sale for his sculptures in America, my brother had purchased a bust of Cicero. He professed to have copied this piece from an antique dug up with his own hands in the environs of Modena. Of the truth of his assertions we were not qualified to judge; but the marble was pure and polished, and we were contented to admire the performance, without waiting for the sanction of connoisseurs. We hired the same artist to hew a suitable pedestal from a neighbouring quarry. This was placed in the temple,and the bust rested upon it. Opposite to this was a harpsichord, sheltered by a temporary roof from the weather. This was the place of resort in the evenings of summer. Here we sung, and talked, and read, and occasionally banqueted. Every joyous and tender scene most dear to my memory, is connected with this edifice. Here the performances of our musical and poetical ancestor were rehearsed. Here my brother’s children received the rudiments of their education; here a thousand conversations, pregnant with delight and improvement, took place; and here the social affections were accustomed to expand, and the tear of delicious sympathy to be shed.”

- Anonymous, July 6, 1799, describing in the Spectator Vauxhall Garden, New York, NY (quoted in Eberlein and Hubbard 1944: 171)[7]

- “His beautiful garden was opened at 6 o'clock in the morning, and the colours were hoisted under a discharge of 16 guns. The 16 summer houses being the names of the Sixteen United States, each were decorated with the Emblematical Colours belonging to each State, and ornamented with Flowers and Garlands. At 5 o'clock in the evening, the sixteen colours of each Summer-house were carried,at the sound of the music, to the Grand Temple of Independence, which is 20 feet diameter, and 20feet high. . . in the middle of which was presented,the Bust of the great Washington as large as life, and near him a Grand Gold Column, representing the Constitution, and below the said Column the Figure of Fame, 6 feet high, presenting to him with one hand a Crown of Laurel, and with the other holding a Trumpet, announcing to the public that she crowns Real Merit. Round the Pedestal were seen Military Trophies. The sixteen colours above mentioned were placed round the Pedestal, at the sound of Martial Music—and at each colour being placed round the Bust it was announced by the firing of cannon.”

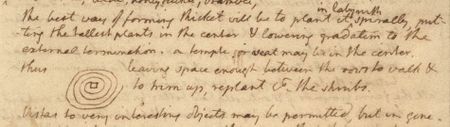

- Jefferson, Thomas, c. 1804, describing Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, VA (Massachusetts Historical Society, Coolidge Collection, manuscript N171; K162)

- “at the Rocks build a turning Tuscan temple 10 f. diam. 6 columns proportions of Pantheon. . .

- “at the Point build Demosthenes’s lantern. . .

- “The best way of forming thicket will be to plant it in labyrinth spirally, putting the tallest plants in the center and lowering gradation to the external termination. a [sic] temple or seat may be in the center, thus leaving space enough between the rows to walk & to trim up, replant [a three pronged diagram of] the shrubs. . . . [Fig. 7]

- “Temples or seats at those spots on the walks most interesting either for prospect, or the immediate scenery.

- “The Broom wilderness on the South side to be improved for winter walking or riding, conducting a variety of roads through it, forming chambers with seats, well sheltered from winds, &spread before the sun. a temple with yellow glass panes would suit these, as it would give the illusion of sunshine in cloudy weather.”

- Peale, Charles Willson, June 12, 1804, describing the Carroll Garden, Annapolis, MD (Miller et al., eds., 1988: 2:704)[8]

- “at each end of the wall is an octagon Building projecting beyond it, one is a Summer House & probably the other is a Temple, it is locked up, &at first sight they might be thought to be intended for such purposes but on finding that one has no holes, People are naturally led to believe that the internal structure is similar, since the outsides are perfectly so.” [Fig. 8]

- Cuming, Fortescue, 1810, describing Grants Hill, property of Col. James O'Hara, Pittsburgh, PA (1810: 226)[9]

- “Was the general to fence it in, terrace it, which could be done at a small expense, ornament it with clumps of evergreens and flowering shrubs,and erect a few banqueting houses in the forms of small temples according to the different orders of architecture, it would be one of the most beautiful spots, which not only America, but perhaps any town in the universe could boast of.”

- Waln, Robert, Jr., 1825, describing the Friends Asylum for the Insane, near Frankford, PA (1825: 232–33)[10]

- “A shaded, serpentine walk, now skirting the edge of the wood, now plunging into its dark and dependent foliage, and embracing, in its windings, more than a mile, leads over a neat and lightly constructed bridge, to a pleasure-house, which might justly be termed the Temple of Solitude. It is securely founded on a rock, which juts abruptly forth from the declivity of a steep hill, three sides of which are almost perpendicular, and of considerable height. . . The straight and towering tulip-tree, the sturdy oak, the chestnut, and the beech, cast their cool shadows around this wood-embossed abode of contemplation. . . The light and airy fabric, perched on the brow of the rock, could alone betray to the enchanted visiter [sic], that this sweet, lonely, and romantic retreat, had ever before been explored by man.”

- Peale, Charles Willson, c. 1825, describing New York, NY (Miller et al., eds., 2000: 5:248)[11]

- “Walking with Mrs. Peale one evening to take the fresh air at the Battery, in those pleasant gravelly walks skirted with Trees. Adjoining to these pleasure grounds they observed places of entertainment brilliantly lighted up with lamps and to regaile the Ear a variety of Musick—they are called Gardens, small but neatly fitted up with boxes and seats, walks divided by small beds of flowers. In the center of that they visited was a circular sort of Temple with an ornamented vase in the center, round the cornich [cornice] of this temple a considerable number of lamps, the light of which shew a number of small jets from the vaseof waters thrown as high as the cornish. perhaps this fountain gets its supply of water from some resevoir in the adjacent building, and by pipes beneath the walks conveyed to the Vase. They paid 1/4$ for each ticket, which purchases Ice creams, Cakes or other refreshments as may be choosen to the value. There was another Garden near this where the company are regailled with vocal musick.”

- Anonymous, April 28, 1826, "On Landscapes and Picturesque Gardens" (New England Farmer 4: 316)[12]

- “Mr. [Andrew] P[armentier]. by the advice of several of his friends, will furnish plans of landscape and picturesque gardens; he will communicate to gentlemen who wish to see him, a collection of his drawings of Cottages, Rustic Bridges, Dutch, Chinese, Turkish, French Pavilions, Temples, Hermitages, Rotundas, &c. For further particulars, inquiries personally, or by letter, addressed to him, post paid, will be attended to.”

- Story, Joseph, September 24, 1831, describing Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, MA (1831: 29)[13]

- “Whenever the funds of the corporation shall justify the expense, it is proposed that a small Grecian or Gothic Temple shall be erected on a conspicuous eastern eminence, which in reference to this allotment has received the prospective name of Temple Hill.”

- Biddle, Jane, September 14, 1835 or 1836, describing Andalusia, seat of Nicholas and Jane Biddle, near Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Wainwright 1976: 24)[14]

- “The carpenters have begun upon the Billiard Room, & we find that one part of the plan cannot be accomplished, that of raising the little temple in proportion to what is taken off it by the slanting roof. It has therefore at present so clumsy an appearance that I have stopped them from going on till you can see it. . . They hung a pair of shutters between the pillars, which improved the appearance of it, but does not destroy the bad effect of concealing parts of the pillar.” [Fig. 9]

- Committee of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, September 1845, describing its annual exhibition in Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Boyd 1929: 99)[15]

- “John Maguire, gardener to Joshua Longstreth, exhibited ‘a large round temple about sixteen feet in height terminating with a cone-shaped spire of one-third its altitude, enveloped with green and flowers in profusion.’”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, October 1847, describing Montgomery Place, country home of Mrs. Edward (Louise) Livingston, Dutchess County, NY (Horticulturist 2: 158)[16]

- “. . . we suddenly behold, with a feeling of delight, THE LAKE.

- “Nothing can have a more charming effect than this natural mirror in the bosom of the valley. It is a fine expansion of the same stream, which farther down forms the large cataract. Here it sleeps, as lazily and glassily as if quite incapable of aught but reflecting the beauty of the blue sky, and the snowy clouds, that float over it. On two sides, it is overhung and deeply shaded by the bowery thickets of the surrounding wilderness; on the third is a peninsula, fringed with the graceful willow, and rendered more attractive by a rustic temple; while the fourth side is more sunny and open, and permits a peep at the distant azure mountain tops.

- “This part of the grounds is seen to the most advantage, either toward evening, or in moonlight. Then the effect of contrast in light and shadow is most striking, and the seclusion and beauty of the spot are more fully enjoyed than at any hour. Then you will most certainly be tempted to leave the curious rustic seat, with its roof wrapped round with a rude entablature like Pluto’s crown; and you will take a seat in Psyche’s boat, on whose prow is poised a giant butterfly, that looks so mysteriously down into the depths below.” [Fig. 10]

Citations

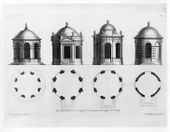

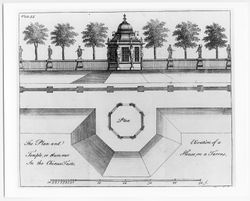

- Gibbs, James, 1728, A Book of Architecture (1728: xviii, xix)[17]

- “The Plan, Upright and Section of a Building of the Dorick Order in form of a Temple, made for a Person of Quality, and propos'd to have been placed in the Center of four Walks; so that a Portico might front each Walk. Here is a large Octagonal Room of 22 feet and 26 feet high, adorn'd with Niches and crown'd with a Cupola. All the Ornaments of the Inside are to be of Plaister; and the Outside of Stone. . . [Fig. 11]

- “A circular Building in form of a Temple, 20 feet in Diameter, having a Peristylium round it of the Dorick Order, and adorn'd with a Cupola; erected in his Grace the Duke of Bolton’s Garden at Hackwood, upon the upper ground of an Amphitheatre, back'd with high Trees that render the Prospect of the Building very agreeable.”

- Chambers, Ephraim, 1741–43, Cyclopaedia (2:n.p.)[18]

- “TEMPLE, in architecture.—The ancient temples were distinguished, with regard to their construction, into various kinds; as,

- “TEMPLE in antae. . .

- “Tetrastyle-TEMPLE. . .

- “Prostyle-TEMPLE. . .

- “Amphiprostyle, or double prostyle-TEMPLE. . .

- “Periptere-TEMPLE. . .

- “Diptere-TEMPLE.”

- Ware, Isaac, 1756, A Complete Body of Architecture (1756: 636, 641, 650)[19]

- “The first principle is here that there be space to walk, and seats to rest. These must be proportioned also to one another: it would be absurd to terminate a vast walk with a plain bench; nor less ridiculous to erect a pompous temple where there was not the extent of a hundred yards from the building. . .

- “He who would know where to place his pavilion, seat, or temple, in a garden, must first understand what the purpose of it is, and what the true beauty and excellence of the garden itself. . .

- “Thus may the groves be constructed ornamentally to the other parts of the garden, elegant and pleasing in themselves, and fit to form recesses in which to place statues, temples, and other structures.”

- Whately, Thomas, 1770, Observations on Modern Gardening (1770; repr., 1982: 128–29)[20]

- “The choice of situations is also very free; circumstances which are requisite to particular structures, may often be combined happily with others, and enter into a variety of compositions. . . A Grecian temple, from its peculiar grace and dignity, deserves every distinction; it may, however, in the depth of a wood, be so circumstanced, that the want of those advantages to which it seems entitled, will not be regretted.”

- Sheridan, Thomas, 1789, A Complete Dictionary of the English Language (n.p.)[21]

- “TEMPLE, tem’pl. s. . . an ornamental building in a garden.”

- Marshall, William, 1803, On Planting and Rural Ornament (1:265)[22]

- “THERE is another species of useless ornament, still more offensive, because more costly, than those comparatively innocent eye-traps; we mean TEMPLES. Whether they be dedicated to Bacchus, Venus, Priapus, or any other god or goddess of debauchery, they are, in this age, enlightened with regard to theological andscientific knowledge, equally absurd.”

- M'Mahon, Bernard, 1806, The American Gardener’s Calendar (1806: 58, 64)[23]

- “In various parts of the pleasure-ground, leave recesses and other places surrounded with clumps of trees and shrubs, for the erection of garden edifices, such as temples, grottos, rural seats, statues, &c. . . .

- “In some spacious pleasure-grounds various light ornamental buildings and erections are introduced, as ornaments to particular departments; such as temples, bowers, banquetting houses, alcoves, grottos, rural seats, cottages, fountains, obelisks, statues, and other edifices; these and the like are usually erected in the different parts, in openings between the divisions of the ground, and contiguous to the terminations of grand walks, &c.

- “Some of these kinds of ornaments, however, being very expensive, are rather sparingly introduced; sometimes a temple is presented at the termination of a grand walk or opening, or sometimes a temple, banqueting-house, or bower is erected in the centre of some spacious opening or grass-ground in the internal divisions."

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826: 356, 809)[24]

“1808. Temples, either models or imitations of the religious buildings of the Greeks and heathen Romans, are sometimes introduced in garden-scenery to give dignity and beauty. In residences of a certain extent and character, they may be admissible as imitations, as resting-places, and as repositories of sculptures or antiquities. Though their introduction had been brought into contempt by its frequency, and by bad imitations in perishable materials, yet they are not for that reason to be rejected by good taste. They may often add dignity and a classic air to a scene; and when erected of durable materials, and copied from good models, will, like their originals, please as independent objects. . .

- “6156. Decorations in shrubberoes. Those of the shrubbery should in general be of a more useful and imposing character than such as are adopted in the flower-garden. . .Open and covered seats are necessary, or, at least, useful decorations, and may occur here and there in the course of the walk, in various styles of decoration, from the rough bench to the rustic hut. . . and Grecian temple. (fig. 52)" [Fig. 12]

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828: n.p.)[25]

- “TEM'PLE, n. [Fr.; L. templum; It. tempio; Sp. templo; W. temyl, temple, that is extended, a seat; temlu, for form a seat, expanse or temple; Gaelic, teampul.]

- “1. A public edifice erected in honor of some deity. Among pagans, a building erected to some pretended deity, and in which the people assembled to worship.”

- Johnson, George William, 1847, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening (1847: 581)[26]

- “TEMPLES dedicated to some deity of the heathen mythology, as to Pan in a grove, or to Flora among bright sunny parterres, are not inappropriate, if the extent of the grounds and the expenditure on their management allow them to be of that size, and of that correctness of style, which can alone give the classic air and dignity which are their only sources of pleasure.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, February 1848, “Hints and Designs for Rustic Buildings” (Horticulturist 2: 363)[27]

- “It must be a very highly finished scene, and a garden where all the details are in a very decided and ornate style of art, in which marble temples, statues, or even highly finished pavilions and summer-houses, may be introduced with harmony and propriety.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1849, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849: repr., 1991: 382–83, 456, 507)[28]

- “Grecian architecture in its pure form, viz. the temple, when applied to the purposes of domestic life, makes a sad blow at both these established rules [of fitness and expression of purpose]. . .

- “The temple and the pavilion are highly finished forms of covered seats, which are occasionally introduced in splendid places, where classical architecture prevails. . .

- “86, The Chinese temple, on the highest part of the mount formed of the soil taken from the excavation now constituting the pond. The view from the interior of this temple is shown in Fig. 9, p. 504. [Fig. 13]

Images

Inscribed

James Gibbs, “The Plan, Upright and Section of a Building of the Dorick Order in the form of a Temple,” in A Book of Architecture (1728), pl. 67.

James Gibbs, “A Circular Building in the Form of a Temple,” in A Book of Architecture (1728), pl. 72.

William and John Halfpenny, “The Plan and Elivation of a Temple, or Summer House, on a Tarras, In the Chinese Taste,” in Rural Architecture in the Chinese Taste (1755), pl. 44.

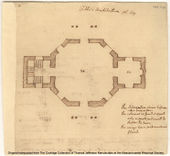

Thomas Jefferson, A temple for a garden at Monticello (after Gibbs), c. 1780.

Thomas Jefferson, Letter describing plans for a “Garden Olitory” [detail], c. 1804. “The best way of forming thicket will be to plant it in labyrinth spirally. . . a temple. . . may be in the center”

J. C. Loudon, “Grecian temple,” in An Encyclopædia of Gardening (1826), p. 809, fig. 562.

J. C. Loudon, “View from the Chinese Temple,” Cheshunt Cottage, in Gardener’s Magazine 15, no. 117 (December 1839): 651, fig. 162.

Associated

Thomas Jefferson, Plan showing the rectangular flower beds and proposed temples at the corners of the terrace walks at Monticello, before August 4, 1772.

Thomas Jefferson, Design for a decorative outchamber at Monticello, c. 1778.

Anonymous, “The Lake,” Montgomery Place, in A. J. Downing, ed., Horticulturist 2, no. 4 (October 1847): 158, fig. 27.

Attributed

James Gibbs, “Four Summer-houses in form of Temples,” in A Book of Architecture, containing designs of buildings and ornaments (1728), pl. 79.

Thomas Jefferson, Design for a garden temple and dovecote at Monticello, c. 1778.

Thomas Jefferson, A garden temple at Monticello (after Gibbs), c. 1780.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Houses and a church. Spring house—elevation and plan, 1795–99.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Houses and a church. Garden temple elevations and floor plan, c. 1795–99.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Houses and a church. Side elevation and basement floor plan, c. 1795–99.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Houses and a church. Lodge—Sections showing interior elevation, c. 1795–99.

Charles Willson Peale, Letter to Angelica Peale describing his garden at Belfield [detail], November 22, 1815.

Charles Willson Peale, View of the garden at Belfield, 1816.

Charles Willson Peale, View of the garden at Belfield [detail], 1816.

Anonymous, “The Shrubbery and Flower Garden,” in Cultivator 5, no. 4 (April 1848): 114.

Alexander Jackson Davis, Octagonal Garden Structure for Montgomery Place, c. 1850

Notes

- ↑ Therese O’Malley, “Charles Willson Peale’s Belfield, Its Place in American Garden History,” in New Perspectives on Charles Willson Peale, ed. Lillian B. Miller and David C. Ward (Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press for the Smithsonian Institution, 1991), 272, view on Zotero.

- ↑ William L. Beiswanger, “The Temple in the Garden: Thomas Jefferson’s Vision of the Monticello Landscape,” Eighteenth Century Life 8 (January 1983): 170–88, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Hannah Callender Sansom, The Diary of Hannah Callender Sansom: Sense and Sensibility in the Age of the American Revolution, ed. Susan E. Klepp and Karin Wulf (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2010), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson, The Garden Book, ed. Edwin M. Betts (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1944), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Constantia [Judith Sargent Murray], “Description of Gray’s Gardens, Pennsylvania,” Massachusetts Magazine, or, Monthly Museum of Knowledge and Rational Entertainment 7, no. 3 (July 1791): 413–17, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Brockden Brown, Wieland, or The Transformation, An American Tale (New York: T. & J. Swords, 1798), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Harold Donaldson Eberlein and Cortlandt Van Dyke Hubbard, “The American ‘Vauxhall’ of the Federal Era Article Stable,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography (April 1944): 68, 150–74, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Lillian B. Miller et al., eds., The Selected Papers of Charles Willson Peale and His Family: Charles Willson Peale: Artist in Revolutionary America, 1735–1791, vol. 2, The Artist as Museum Keeper, 1791–1810 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1988), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Fortescue Cuming, Sketches of a Tour to the Western Country (Pittsburgh: Cramer, Spear and Eichbaum, 1810), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Robert Waln Jr., "An Account of the Asylum for the Insane, Established by the Society of Friends, near Frankford, in the Vicinity of Philadelphia," Philadelphia Journal of the Medical and Physical Sciences 1 (new series) (1825): 225–51, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Lillian B. Miller et al., eds., The Selected Papers of Charles Willson Peale and His Family: Charles Willson Peale: Artist in Revolutionary America, 1735–1791, vol. 5, The Autobiography of Charles Willson Peale (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, “On Landscape and Picturesque Gardens,” New England Farmer 4, no. 40 (April 28, 1826): 316, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Joseph Story, An Address Delivered on the Dedication of the Cemetery at Mount Auburn (Boston: Joseph T. and Edwin Buckingham, 1831), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Nicholas B. Wainwright, Andalusia: Countryseat of the Craig Family and of Nicholas Biddle and His Descendants (Philadelphia: Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1976), view on Zotero.

- ↑ James Boyd, A History of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1827–1927 (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1929), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. Downing, “A Visit to Montgomery Place,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 2, no. 4 (October 1847): 153–60, view on Zotero.

- ↑ James Gibbs, A Book of Architecture, Containing Designs of Buildings and Ornaments, 2nd ed. (London: W. Innys and R. Manby, 1739), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Ephraim Chambers, Cyclopaedia, or An Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences. . . , 5th ed., 2 vols. (London: D. Midwinter et al., 1741), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Isaac Ware, A Complete Body of Architecture (London: T. Osborne and J. Shipton, 1756), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Whately, Observations on Modern Gardening, 3rd ed. (1770; repr., London: Garland, 1982), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas A. Sheridan, A Complete Dictionary of the English Language, Carefully Revised and Corrected by John Andrews. . . , 5th ed. (Philadelphia: William Young, 1789), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Marshall, On Planting and Rural Ornament: A Practical Treatise. . . , 2 vols. (London: G. and W. Nicol, G. and J. Robinson, T. Cadell, and W. Davies, 1803), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bernard M'Mahon, The American Gardener’s Calendar: Adapted to the Climates and Seasons of the United States. Containing a Complete Account of All the Work Necessary to Be Done. . . for Every Month of the Year. . . (Philadelphia: printed by B. Graves for the author, 1806), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, 4th ed. (London: Longman et al., 1826), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ George William Johnson, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening, ed. David Landreth (Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1847), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. Downing, “Hints and Designs for Rustic Buildings,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 2, no. 8 (February 1848): 363–65, view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. [Andrew Jackson]Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America, 4th ed. (1849; repr., Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1991), view on Zotero.