Difference between revisions of "Pond"

V-Federici (talk | contribs) m (→Inscribed) |

V-Federici (talk | contribs) m |

||

| Line 64: | Line 64: | ||

| − | [[File:0056.jpg|thumb|252 px|Fig. 6, [[John Bartram|John]] or [[William Bartram]], | + | [[File:0056.jpg|thumb|252 px|Fig. 6, [[John Bartram|John]] or [[William Bartram]], "A Draught of [[Bartram_Botanic_Garden_and_Nursery|John Bartram’s House and Garden]] as it appears from the River", 1758.]] |

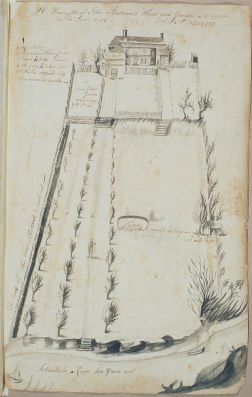

[[File:0722.jpg|thumb|Fig. 7, Anonymous, “Barrell Farm,” Pleasant Hill, 1817. A “fish pond” is situated near the Poplar [[Grove]].]] | [[File:0722.jpg|thumb|Fig. 7, Anonymous, “Barrell Farm,” Pleasant Hill, 1817. A “fish pond” is situated near the Poplar [[Grove]].]] | ||

*Anonymous, February 23, 1786, describing in the ''State Gazette'' a [[pleasure garden]] in Charleston, SC (quoted in Briggs 1951: 103)<ref>Loutrel Winslow Briggs, ''Charleston Gardens'' (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1951), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/A3NA59DZ view on Zotero].</ref> | *Anonymous, February 23, 1786, describing in the ''State Gazette'' a [[pleasure garden]] in Charleston, SC (quoted in Briggs 1951: 103)<ref>Loutrel Winslow Briggs, ''Charleston Gardens'' (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1951), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/A3NA59DZ view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| Line 316: | Line 316: | ||

Image:0480.jpg|Francis Dewing after John Bonner, ''A New Plan of ye Great Town of Boston in New England in America'', 1743. | Image:0480.jpg|Francis Dewing after John Bonner, ''A New Plan of ye Great Town of Boston in New England in America'', 1743. | ||

| − | Image:0056.jpg|[[John Bartram|John]] or [[William Bartram]], | + | Image:0056.jpg|[[John Bartram|John]] or [[William Bartram]], "A Draught of [[Bartram_Botanic_Garden_and_Nursery|John Bartram’s House and Garden]] as it appears from the River", 1758. |

Image:0994.jpg|Anonymous, “Williamsburgh & the slip of land between York & James rivers from thence to Hampton,” c. 1781. | Image:0994.jpg|Anonymous, “Williamsburgh & the slip of land between York & James rivers from thence to Hampton,” c. 1781. | ||

Revision as of 11:41, January 28, 2021

History

The terms pond, lake, and, to a lesser extent, “pool,” were used to describe still-water features in garden settings in American landscape writing. Distinctions between them were not consistently made in dictionaries, treatises, or usage examples, and several of these sources used them synonymously. William Bartram, for instance, used the terms “lake” and “pond” interchangeably when describing Lake George, Georgia, in 1791. Nehemiah Cleaveland, in his 1847 guide to Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York, was also undecided as to whether the bodies of water of “different size and shape” were either small lakes or ponds. A. J. Downing (1849) suggested that the terminology differed from British usage because of the abundance and scale of America’s natural waterways: “many a beautiful, limpid, natural expanse which in England would be thought a charming lake, is here simply a pond.” The first American edition of the Encyclopaedia (1798) stated flatly that “A pool and a pond are the same.” Noah Webster (1828) was clear in his distinction between a pond and a lake, with the latter being larger, and between a pond and a pool, but even Webster noted that the term “pool” was “used by writers with more latitude.” He also defined pool as “a small collection of water in a hollow place, supplied by a spring, and discharging its surplus water by an outlet. It is smaller than a lake, and in New England is never confounded with pond or lake. It signifies with us, a spring with a small bason or reservoir on the surface of the earth.”[1]

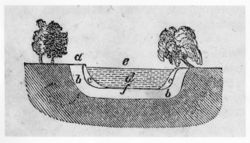

Despite this ambiguity, it is clear that ponds were a common element in the American landscape throughout the colonies in the period under discussion. Their construction method was determined more by setting and function than by chronological or regional patterns. Garden ponds were created by damming streams, capturing natural springs, or capitalizing on existing ponds [Fig. 1]. George William Johnson's A Dictionary of Modern Gardening (1847) detailed the method of “puddling” ponds with clay to improve their retention of water, and J. C. Loudon (1826) illustrated several methods of constructing ponds or cisterns [Fig. 2].[2] Downing's lengthy discussion about the “Treatment of Water” went into detail about the excavation of a “piece of artificial water,” the placement of islands, and the planting and arrangement of banks.[3] In one of the few examples where artificial materials are specified in the description of a site, a Charleston property was advertised in 1768 with two fish ponds “neatly bricked in.”

Ponds in gardens were used for a variety of practical uses, ranging from ice harvesting to stocking fish and waterfowl, from irrigating gardens to supplying fountains, and from fire fighting to wetting dusty roads. The terms “horse pond,” “dam pond,” “mill pond,” “fish pond,” and “ice pond” reflect these functions, but their usage does not preclude the perception that these still-water features were integral to the garden design. At Crowfield, on the Ashley River, Eliza Lucas Pinckney (1743) reported that the fish ponds were disposed to “form a fine prospect of water from the house.” Ponds were also valued as a source of water for the garden and for creating specialized habitats [Fig. 3]. Manasseh Cutler reported in 1787 that the Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery near Philadelphia contained an “artificial pond [with] . . . a good collection of aquatic plants.” Treatise writers and nurserymen such as James E. Teschemacher (1835), Robert Buist (1841), and Charles Wyllys Elliott (1848) advocated the same practice of creating ponds to take advantage of the many swamp plants unique to America. In addition, ponds were associated with recreation; they were used for swimming, angling, boating, skating, and even a miniature “Atlantic” for children’s toy schooners, as described by Nehemiah Adams in 1842.

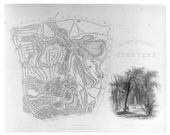

In landscape design theory, the configuration of a pond depended on its context. Downing argued that the shape of a pond must conform to its surroundings with geometric shapes suitable for architectural or flower gardens while irregular lines were recommended in picturesque or modern-style gardens.[4] In keeping with the monumentality and geometric regularity of the city plan, elliptical ponds were proposed for the Columbian Institute in Washington, DC. Irregular ponds described by H. A. S. Dearborn in 1831 as “small ponds and morasses converted into picturesque sheets of water” were a major element of the naturalistic design at Mount Auburn Cemetery [Fig. 4]. Ponds were recommended particularly for soggy, low areas, although Edward Sayers (1837) and Downing (1851) cautioned strongly against building a pond unless it had a water supply year-round. Treatise writers also suggested ways to enhance existing natural ponds by planting along the banks. Sayers, for example, praised “drooping willows and trees of a pendulous habit for shade” and others admired the effects of lilies and water plants. C. M. (Charles Mason) Hovey (1839) offered an example of pond plantings gone awry at the Elias Hasket Derby House in Salem, Massachusetts, where the thirty-year old buckthorn hedge had grown to an impenetrable eight-foot barrier around the small fish pond. Treatises also suggested the addition of bridges in order for the pond or lake to appear as a river, and even adding elaborate ornaments such as a mount (as at William Middleton’s Crowfield), a fountain (as at Charles Willson Peale's Belfield), or a grotto (as at Henry Pratt’s Lemon Hill). Jane Loudon (1845) argued that a pond’s appeal, like a lawn’s, lay in its expanse of unbroken space, and she suggested that if any islands were to be added that they should be kept near the shore.

Bodies of standing water, whether called ponds, lakes, or pools, provided many of the same visual effects, and writers praised the associations of coolness and the animating quality that water brought to a garden.[5] As Downing noted, animation might come from the sparkle of the reflecting sun, the movement of wind on the water, or from the sound of a fountain or a stream feeding the pond. Water was prized, as Abercrombie (1817) noted, as a natural mirror reflecting the surrounding vegetation or, as at the carefully placed pond at Monticello and in a painting of an unknown site [Fig. 5], the house itself. Bodies of water not only sustained fish for sport and food, but, as Humphry Repton (1803) advised, they also attracted waterfowl and other animals and thus enhanced visual and aural interest of the garden. Downing (1847) praised the effect of contrasting water features, such as the rush of the waterfall at Blithewood, on the Hudson, juxtaposed with the still waters of the lake, “so full of the spirit of repose.”

—Elizabeth Kryder-Reid

Texts

Usage

- Anonymous, July 28, 1733, describing a property for sale in Charleston, SC (South Carolina Gazette)

- “A Plantation about two Miles above Goose-Creek Bridge. . . [having] a Garden of each Side of the House, with Posts, Rails and Pails of the best Stuff, all plained & painted, & brick’d underneath, a Fish-pond well stored with Perch, Roach, Pike, Eels and Cat-fish. . . a Spring within 3 Stones throw of the House, intended for a Cold Bath, and House over it, 3 large Dam-ponds, whose Banks with some small Repairs, may drown upwards of 100 Acres of Land, which being very plentifully stored with Game all the Winter Season, affords great Diversion.”

- Pinckney, Eliza Lucas, c. May 1743, describing Crowfield, plantation of William Middleton, vicinity of Charleston, SC (1972: 61)[6]

- “come to the bottom of this charming spott where is a large fish pond with a mount rising out of the middle—the top of which is level with the dwelling house and upon it is a roman temple. On each side of this are other large fish ponds properly disposed which form a fine prospect of water from the house.”

- Kalm, Pehr, November 12, 1748, describing the springs in Pennsylvania (1937: 1:161)[7]

- “Not only people of rank but even others that had some possessions, frequently had fish ponds in the country near their homes.”

- Murray, John, June 18, 1753, describing Murraywhaite, home of John Murray, Charleston, SC (Scottish Record Office, Murraywhaithe Collection, GO219/284/5)

- “By all means mention the fine Improvements of your garden & the fine avenues you’ve raised near the spot where you’r to build your new house. I hope you’ll raise it in the English Taste. . . You’ll certainly dig a Fish pond & another for geese & Ducks & one Swan. . .”

- Drowne, Samuel, June 23, 1767, describing Malbone Hall, country seat of Godfrey Malbone, Newport, RI (Brown University, John Hay Library, Drowne Family Papers, typescript)

- “I went up to Colonel Molbones House or the ruins of His House there was a fine garden and Summer House. There His House was Built of Stone and marvel had Six Chimneys and in His garden was a fish pond and a Duck pond the water was Drawn out of the fish pond when His House was Burnt.”

- Anonymous, December 12, 1768, describing in the South Carolina and American General Gazette a property in the vicinity of Charleston, SC (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “For Sale, by private Contract, A LOT of LAND on White-Point. . . on which there is a. . . brick summer-house, with two fish ponds neatly bricked in, and several other convenience.”

- Quincy, Josiah, May 3, 1773, describing the country seat of John Dickinsen, near Philadelphia, PA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “This worthy and arch-politician. . . here enjoys otium cum dignitate as much as any man. Take into consideration the antique look of his house, his gardens, green-house, bathing-house, grotto, study, fish-pond, fields, meadows, vista, through which is distant prospect of Delaware River.”

- Anonymous, February 23, 1786, describing in the State Gazette a pleasure garden in Charleston, SC (quoted in Briggs 1951: 103)[8]

- “An enclosure of about 20 acres in this plat, adjoining the marsh, and in full view of Wallace’s ferry, is set apart for a PLEASURE GARDEN; about seven or eight acres of this, including three canals or fish-ponds are already laid out and improved in a taste no where exceeded in this State. The canals abound with fish.”

- Cutler, Manasseh, July 14, 1787, describing Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery, vicinity of Philadelphia, PA (1987: 1:273)[9]

- “It [the garden] is finely situated, as it partakes of every kind of soil, has a fine stream of water, and an artificial pond, where he has a good collection of aquatic plants.” [Fig. 6]

- Bentley, William, June 12, 1791, describing Pleasant Hill, seat of Joseph Barrell, Charlestown, MA (1962: 1:264)[10]

- “Was politely received at dinner by Mr Barrell, & family, who shewed me his large & elegant arrangements for amusement, & philosophic experiments. . . His Garden is beyond any example I have seen. A young grove is growing in the back ground, in the middle of which is a pond, decorated with four ships at anchor, & a marble figure in the centre.” [Fig. 7]

- Clitherall, Eliza Caroline Burgwin, active 1801, describing the Hermitage, seat of John Burgwin, Wilmington, NC (quoted in Flowers 1983: 125)[11]

- “The Gardens were large, and laid out in the English style—a Creek wound thro’ the largest, upon its banks grew native shrubbery; in this Garden were several Alcoves, Summer Houses, a hothouse—an Octagon summer house high and a Gardener’s tool house beneath—a fishpond, communicating with the Creek, both producing abundance of fish.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, c. 1804, describing improvements for Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, VA (quoted in Martin 1991: 157)[12]

- “a fish pond to be visible from the house.”

- Peale, Charles Willson, March 15, 27, 29, 1814, in a letter to his sons, Benjamin Franklin Peale and Titian Ramsey Peale, describing Belfield, estate of Charles Willson Peale, Germantown, PA (Miller et al., eds., 1991: 3:239)[13]

- “when my leasure and I can spare a man to hall dirt I will raise the water in the fish Pond which will encrease its surfaces considerably raising the water to the stone wall at the head of the Pond, deeper, and more water, will be better for fish & will raise the get [[[jet]]] at the fountain considerably.”

- Columbian Institute, 1823, in a report describing the Columbian Institute, Washington, DC (quoted in O’Malley 1989: 127)[14]

- “An elliptical pond had been formed 144 feet for the transverse and 100 feet for the conjugate diameter, with an island in the middle 114 feet by 85 feet.”

- Peale, Charles Willson, c. 1825, describing Belfield, estate of Charles Willson Peale, Germantown, PA (Miller et al., eds., 2000: 5:382)[15]

- “Having a good spring-house the water from it supplied a small fish-pond, in which he put many cat-fish brought from the Schulkill and although they lived and perhaps might be breed there yet being petts never was served at his table.”

- Wailes, Benjamin L. C., December 29, 1829, describing Lemon Hill, estate of Henry Pratt, Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Moore 1954: 359)[16]

- “But the most enchanting prospect is towards the grand pleasure grove & green house of a Mr. Prat[t], a gentleman of fortune, and to this we next proceeded by a circutous [sic] rout, passing in view of the fish ponds, bowers, rustic retreats, summer houses, fountains, grotto, &c., &c. . . . Next is a round fish pond with a small fountain playing in the pond. An Oval & several oblong fish ponds of larger size follow, & between the two last is an artificial cascade. Several summer houses in rustic style are made by nailing bark on the outside & thaching the roof. There is also a rustic seat built in the branches of a tree, & to which a flight of steps ascend. In one of the summer houses is a Spring with seats around it. The houses are all embelished [sic] with marble busts of Venus, Appollo, Diana and a Bacanti. One sits on an Island on the fish pond. All the ponds filled with handsome coloured fish.”

- Committee of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1830, describing Lemon Hill, estate of Henry Pratt, Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Boyd 1929: 432)[17]

- “There are some pretty bowers, summer houses, grottos and fish ponds in this garden—the latter well stored with gold and silver fish.”

- Dearborn, H. A. S., September 30, 1831, describing Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, MA (quoted in Ward 1831: 48)[18]

- “The nurseries may be established, the departments for culinary vegetables, fruit, and ornamental trees, shrubs and flowers, laid out and planted, a green house built, hot-beds formed, the small ponds and morasses converted into picturesque sheets of water, and their margins diversified by clumps and belts of our most splendid native flowering trees, and shrubs, requiring a soil thus constituted for their successful cultivation, while their surface may be spangled with the brilliant blossoms of Nymphae, and the other beautiful tribes of aquatic plants.”

- Dearborn, H. A. S., 1832, describing Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, MA (quoted in Harris 1832: 80)[19]

- “The upper Garden Pond has been excavated, to a sufficient depth to afford a constant sheet of water, with a fall at the outlet of three feet, and being embanked, avenues with a border of six feet, for shrubs and flowers, have been made all round it. . .

- “Arrangements have been made for excavating, to a greater depth, Forest and Consecration-Dell Ponds, and surrounding them by embellished pathways, like those of Garden-Pond, and for cleaning the eastern portion of Garden and of Meadow Ponds, of bushes and weeds; all which will be done during the winter, that season being the most favorable for such work.” [Fig. 8]

- Forman, Martha Ogle, 17 December 1833, describing Rose Hill, home of Martha Ogle Forman, Baltimore County, MD (1976: 329)[20]

- “The fish pond dam broke. A tremendous storm wind and rain.”

- Anonymous, 1839, describing Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, MA (Picturesque Pocket Companion 1839: Appendix, 41)[21]

- “The streams, and parcels of bog and meadowland may be easily converted into ponds, and variously formed sheets of water, which will furnish appropriate positions for aquatic plants, while their borders may be planted with Rhododendrons, Azaleas, several species of the superb Magnolia, and other plants, which require a constantly humid soil, and decayed vegetable matter, for their nourishment.”

- Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), November 1839, “Notices of Gardens and Horticulture, in Salem, Mass.,” describing Elias Hasket Derby House, Salem, MA (Magazine of Horticulture 5: 411)[22]

- “In the centre of the garden is a small oval pond, containing gold fish: this pond is hedged round with the buckthorn, which has now been planted over thirty years! It is not over eight feet high, and is thickly set with branches and foliage from the top to bottom, and perfectly impenetrable.”

- Adams, Nehemiah, 1842, describing Boston Common, Boston, MA (1842: 19–20)[23]

- “The Common is adorned by a pond of fresh water. . .

- “This pond of water has had, and will continue to have, a powerful influence on the rising generations of this city. With the little child. . . it is his Atlantic, as a place of danger and adventure. . . There are as many clearances and arrivals of boats, sloops and schooners, from its rock-bound shores, during the year, as from most of our sea ports. . . When winter comes, the pond is the scene of as great interest and excitement as in the summer. Its frozen surface is cut by innumerable skates.”

- W., February 1842, describing Lowell Cemetery, Lowell, MA (Magazine of Horticulture 8: 49)[24]

- “The northern and southern boundaries embrace a range of high grounds, covered for the most part with a young and verdant growth of trees: these high grounds gradually and abruptly slope towards the centre or valley, through which runs a brook, supplying several large ponds for the season, also sufficient for supplying a fountain of about one hundred feet head.”

- Longfellow, Alexander W., January 1844, describing the Vassall-Craigie-Longfellow House, Cambridge, MA (quoted in Evans 1993: 38)[25]

- “We were very busy planning the grounds & I laid out a linden avenue for the Professor’s private walk. I was often reminded of your fancy for such things. . . The house is to be repaired but not essentially altered, the old out buildings to be removed, trees planted a pond, & rustic bridge, created the pond is an apology for the bridge.”

- B., P., January 1844, “Progress of Horticulture in Rochester, N.Y.,” describing the residence of John Robert Murray, Mount Morris, NY (Magazine of Horticulture 10: 18)[26]

- “In the rear of the dwelling is a deep ravine, in which there are two fish ponds, with a good supply of trout; from these water is conveyed to the house by means of a forcing pump.”

- Cleaveland, Nehemiah, 1847, describing Green-Wood Cemetery, Brooklyn, NY (1847: vi)[27]

- “To preserve, at all times, the supply and the transparency of the smaller ponds—to facilitate the sprinkling of the roads, and the irrigation of the grounds during periods of drought and dust— and especially to enrich the scenery, already so lovely, with a perfecting charm, the unfailing water of Sylvan Lake has been lifted into an elevated reservoir. Distributing pipes have been laid, and the visiter of the coming season will be refreshed by the sparkling beauty and gentle murmur of fountain and stream.”

- Notman, John, 1848, describing his designs for the Hollywood Cemetery, Richmond, VA (quoted in Greiff 1979: 145)[28]

- “The only piece of water I have considered desirable, is at the debouch of the water into the culvert at the canal; this would be easily dammed by a retaining wall (some twenty or thirty feet from the canal as the line may be) built of sufficient height to dam the water to the desired breadth of pond—this is to be recommended also as a regulator to the emission of the waters of the main run, rendering it placid in its bed, which once cut to the desired size and shape, will be without the trouble and expense of alteration.”

- Kirkbride, Thomas S., April 1848, describing the pleasure grounds and farm of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, Philadelphia, PA (American Journal of Insanity 4: 348)[29]

- “At the extreme end of the deer-park, it is joined by the drying-yard which completes the separation of the sexes in that direction. In this yard, are the wash-house and the pump and pond from which water is raised into the tanks in the dome of the centre building. This pond is supplied from various springs on the premises, and there is ample space in the yard for drying clothes in fine weather.”

- Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), October 1850, “Notes on Gardens and Nurseries,” describing a residence in Cambridge, MA (Magazine of Horticulture 16: 462)[30]

- “The sailing pond, with the exception of the walks around the border, and the planting of a few trees on the island in the centre, have been completed since last year, and a fine boat-house, to combine a bathing-house, &c., was now just being finished.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1851, describing plans for improving the public grounds of Washington, DC (quoted in Washburn 1967: 55)[31]

- “5th: Fountain Park

- “This Park would be chiefly remarkable for its water features. The Fountain would be chiefly supplied from a basin in the Capitol. The pond or lake might either be formed from the overflow of this fountain, or from a filtering drain from the canal. The earth that would be excavated to form this pond is needed to fill up low places now existing in this portion of the grounds.”

Citations

- Johnson, Samuel, 1755, A Dictionary of the English Language (1755: n.p.)[32]

- “[vol. 1] FISH-POND. n.s. [fish and pond] A small pool for fish. . .

- “[vol. 2] POND, n.s. [supposed to be the same with pound, piñoan, Sax. to shut up.] A small pool or lake of water; a bason; water not running or emitting any stream.”

- Hale, Thomas, 1758, A Compleat Body of Husbandry (1758: 2:104–8)[33]

- “Of the advantages of fish ponds. . .

- “It is not only his [the husbandman’s] interest to put a stock of fish into ponds, when he has them; but it may be often worth his while to make ponds for this purpose [of natural advantages]. . .

- “When the ground is fixed upon for making a fish pond, let the undertaker consider, whether there be springs to feed it, or it must depend on the rains: this makes a different management necessary. Ponds that have springs will be safe from drying on an entire flat: but there should be a descent to those which are to support themselves by rains. . .

- “Of the making of fish ponds.

- “He who would make considerable advantage from fish ponds, must have several: some to receive the fish, while others are cleaning; and some for one kind, and others for another. If he put his fish of prey and his others together, he would find a very sorry account.

- “Different ponds also are intended for different uses. Some are for breeding, and others for feeding of the fish. . .

- “The size of the ponds, that must be proportioned to the nature of the ground or the quantity of fish.”

- Deane, Samuel, 1790, The New-England Farmer (1790: 222)[34]

- “POND, a collection of still water.—A millpond is so called, though it gradually receives water in one part, and discharges it in another: So that it is not perfectly still.”

- Anonymous, 1798, Encyclopaedia (1798: 7:542, 554)[35]

- “Narrow rivulets, if they have a constant stream, and are judiciously led about a garden, have a better effect than many of the large stagnating ponds or canals so frequently made in large gardens. . .

- “All inland water is either running or stagnated. when stagnated, it forms a lake or a pool, which differ only in extent; and a pool and a pond are the same.”

- Abercrombie, John, with James Mean, 1817, Abercrombie’s Practical Gardener (1817: 466)[36]

- “Water is a natural MIRROR. . . The inverted images near the banks—the softened brilliancy of the lower sky—the incessant playfulness of atoms, and streams of reflected light, combine to render an ordinary surface of water capable of supplying a mass of picture, more in contrast with the density and immobility of ground than any other object, and yet in perfect harmony with every outline and every tone of colour that the face of earthly things can present. This can be said for the pond or lake, without any reference to the shape of the bank, or inquiry whether that be picturesque or not.”

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826: 339, 1010)[37]

- “1719. Ponds or large basins. . . are reservoirs formed in excavations, either in soils retentive of water, or rendered so by the use of clay. . .

- “1722. Collecting and preserving ice, rearing bees, &c. however, unsuitable or discordant it may appear, it has long been the custom to delegate to the care of the gardener. In some cases also he has the care of the dove-house, fish-ponds, aviary, a menagerie of wild beasts, and places for snails, frogs, dormice, rabbits, &c. but we shall only consider the ice-house, apiary, and aviary, as legitimately belonging to gardening, leaving the others to the care of the gamekeeper, or to constitute a particular department in domestic or rural economy. . .

- “7219. Ponds in different levels, seen in the same view, are very objectionable on this principle. The little beauty they display as spots, ill compensates for the want of propriety; and the leading idea which they suggest, is a question between their present situation and their non-existence. The choice, therefore, as to the situation of water, must ever depend more on natural circumstances than proximity to the mansion. Is then all water to be excluded that is not in the lower grounds? We have no hesitation in answering this question in the affirmative, so far as respects the principal views, and when a lower level than that in which the water is proposed to be placed is seen in the same view. But in respect to recluse scenes, which Addison compares to episodes to the general design, we would admit, and even copy the ponds on the sides or even tops of hills, which may be designated accidental beauties of nature. In confined spots they are often a very great ornament. . . as a proof of which, we have only to observe some of the suburban villas round the metropolis, where a small piece of water often comes in between the house and the public road with the happiest effect.”

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828: 2:n.p.)[38]

- “FISH-POND, n. A pond in which fishes are bred and kept. . .

- “LAKE, n. [G. lache, a puddle; Fr. lac; L. lacus; Sp. It. lago; Sax. luh; Scot. loch; Ir. lough; Ice. laugh. A lake is a stand of water, from the root of lay. Hence L. lagena, Eng. flagon, and Sp. laguna, lagoon.]

- “1. A large and extensive collection of water contained in a cavity or hollow of the earth. It differs from a pond in size, the latter being a collection of small extent; but sometimes a collection of water is called a pond or a lake indifferently. . .

- “POND, n. [Sp. Port. It. pantano, a pool of stagnant water, also in Sp. hinderance, obstacle, difficulty. The name imports standing water, from setting or confining. It may be allied to L. pono; Sax. pyndan, to pound, to pen, to restrain, and L. pontus, the sea, may be of the same family.]

- “1. A body of stagnant water without an outlet, larger than a puddle, and smaller than a lake; or a like body of water with a small outlet. In the United States, we give this name to collections of water in the interior country, which are fed by springs, and from which issues a small stream. These ponds are often a mile or two or even more in length, and the current issuing from them is used to drive the wheels of mills and furnaces.

- “2. A collection of water raised in a river by a dam, for the purpose of propelling mill-wheels. These artificial ponds are called mill-ponds.”

- Cook, Zebedee, Jr., 1830, An Address, Pronounced Before the Massachusetts Horticultural Society (1830: 21)[39]

- “It is not to be denied that large sums have been injudiciously expended in the construction of some of our rural retreats, and more especially in the erection of the house, the preparation of gravel-walks, the construction of observatories, artificial caverns, fish-ponds, etc.”

- Teschemacher, James E., May 1, 1835, “On Horticultural Architecture” (Horticultural Register 1: 161)[40]

- “I shall not at present touch on the choice of ornamental shrubs, and also merely hint now that if the spot possess the enviable qualification of a stream or even a pond (from the former the latter could easily be formed), the cultivation of the beautiful aquatic and swamp plants of this and other countries would create very considerable additional interest and beauty.”

- Sayers, Edward, November 1, 1837, “On Laying out Gardens and Ornamental Plantations” (Horticultural Register 3: 410)[41]

- “In laying out grounds and ornamental gardens, many pleasing appendages may be very appropriately placed, to give a good effect, and appear to have a real meaning: as rustic arbors, ornamental seats, ornamental water, rockeries, and the like additional appendages, which, when properly placed and managed, give a finish to the grounds, and have the most pleasing effect, but when badly done, their absence is better than their presence; for, in such cases, they have the appearance of a feeble effort to accomplish the intended purpose of the design,—for instance, where a pond is made in such a location, that it is nearly all the summer dry; or a tumble-down bridge over a canal or stream of water; a rustic arbor exposed to the burning rays of the sun, finished in too much mechanical order, are incongruities altogether inconsistent to the purpose.

- “A pond or sheet of water has a beautiful effect in low ground, where the observer at once discovers that a low, unsightly and unhealthy piece of ground has been converted into a useful and ornamental purpose.”

- Sayers, Edward, 1838, The American Flower Garden Companion (1838: 131)[42]

- “On the Native American Flower Garden. . . the margin of the pond should be planted with drooping willows and trees of a pendulous habit for shade, under which a rustic seat might be properly placed for the accommodation of those who desire to view the sporting fishes, and other interesting objects by which they are surrounded. Attached to the pond or streams, I recommend a well arranged grass plot, with a few figures cut therein, which should be planted with native herbaceous plants, and dwarf shrubs.”

- Buist, Robert, 1841, The American Flower Garden Directory (1841: 10–11)[43]

- “if access to a spring can be obtained, it will prove a desideratum in completing the whole: it can be available for a fish-pond or an acquarium, or can be converted into a swamp for the cultivation of many of our most beautiful and interesting native plants.”

- Loudon, Jane, 1845, Gardening for Ladies (1845: 413)[44]

- “Water as an element of landscape scenery, is exhibited in small gardens either in ponds or basins, of regular geometrical or architectural forms; or in ponds or small lakes of irregular forms in imitation of the shapes seen in natural landscape. . .

- “Water in imitation of nature should be in ponds or basins of irregular shape; but always so contrived as to display one main feature or breadth of water. A pond, however large it may be, if equally broken throughout by islands, or by projections from the shores, can have no pictorial beauty; because it is without effect and does not form a whole. The general extent and outline of a piece of water being fixed on, the interior of the pond or lake is to be treated entirely as a lawn. If small, it will require no islands; but if so large as to require some, they must be distributed towards the sides, so as to vary the outline and to harmonize the pond with the surrounding scenery, and yet to preserve one broad expanse of water; exactly in the same manner as in varying a lawn with shrubs and flowers, landscape gardeners preserve one broad expanse of turf.”

- Johnson, George William, 1847, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening (1847: 474)[45]

- “PONDS, are reservoirs of water dug out of the soil, and made retentive by puddling with clay their bottoms and sides.

- “Puddling is necessary in almost all instances and the mode of proceeding is thus detailed by Mr. Marnock, in the United Gardeners’ Journal. . . The sides may slope rapidly, or the reverse: if the slope be considerable, sand or gravel to give a clean appearance will be the more likely to be retained upon the facing; plants can be more easily fixed and cultivated; gold-fish also find in these shallow gravelly parts under the leaves of the plants suitable places to deposit their spawn, and without this they are seldom found to breed. Ponds made in this way may be of any convenient size, from a couple of yards upwards to as many acres. The following [Fig. 137.] is the section of a pond thus formed: a indicates the surface of the ground at the edge of the water; b, the puddle; c, the facing to preserve the puddle from injury; d, the water; e, the surface of the latter; and f, the ordinary bottom. When a small pond of this kind is to be made, and the extent of the surface is determine upon and marked out, it will then be necessary to form a second or outer mark, indicating the space required for the wall or side puddle, and about three feet is the proper space to allow for this—the puddle requiring about two feet, and the facing which requires to be laid upon the puddle ought to be about a foot more, making together three feet. Ponds may be made very ornamental, and for suitable suggestions on this point, see Water.” [Fig. 9]

- Elliott, Charles Wyllys, October 1848, “Reviews: Cottages and Cottage Life” (Horticulturist 3: 181–82)[46]

- “Water is always desirable, in the distance and at hand. In very many situations, a spring, or a small stream, will supply the evaporation of a pretty sized pond, in which the lilies and water plants will thrive. The deeper it can be made, the better.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1849, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849; repr., 1991:349–51)[47]

- “When, however, a number of perpetual springs cluster together, or a rill, rivulet, or brook, runs through an estate in such a manner as easily to be improved or developed into an elegant expanse of water in any part of the grounds, we should not hesitate to take advantage of so fortunate a circumstance. Besides the additional beauty . . . the proprietor may also derive an inducement from its utility; for the possession of a small lake, well stocked with carp, trout, pickerel, or any other of the excellent pond fish, which thrive and propagate extremely well in clear fresh water, is a real advantage which no one will undervalue.

- “There is no department of Landscape Gardening which appears to have been less understood in this country than the management of water. . . the occasional efforts that have been put forth in various parts of the country, in the shape of square, circular, and oblong pools of water, indicate a state of knowledge extremely meagre, in the art of Landscape Gardening. The highest scale to which these pieces of water rise in our estimation is that of respectable horse-ponds;—beautiful objects they certainly are not. They are generally round or square, with perfectly smooth, flat banks on every side, and resemble in tameness and insipidity, a huge basin set down in the middle of a green lawn.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, January 1851, “Domestic Notices: Making Fish Ponds” (Horticulturist 6: 54)[48]

- “Many persons have a fancy for making ponds as ornamental features in country places. This should never be done, unless it is first ascertained that there is not only an abundance of water to keep the pond full in the dryest seasons, but also to preserve it clear and fresh. A large pond, covered with weeds and half stagnant, may be useful—but it is far from ornamental. Nothing but a constant overflow—made by a stream running continually into and out of a pond, will keep it so clear and bright as to be really ornamental.”

- L., R. B., June 1851, “On Artificial Rockeries” (Horticulturist 6: 279)[49]

- “Both rockwork and artificial ponds are, in our estimation, dangerous features in ornamental gardens, for any one to meddle with who has not a great deal of taste, or a lively feeling of natural beauty and fitness. We quite agree with our correspondent, that they should occupy secluded spots in the grounds, and that they are never so successful as when they may be wholly mistaken for nature’s own work. A little round pond, like a soup basin, set in an open, smooth lawn, and a pile of rocks heaped up upon a formal mound, as we have sometimes seen them, in the midst of high artificial flower garden scenery, are equally offensive to good sense and good taste. Nature puts her small pools of water, and her ledge of rocks filled with mosses and ferns, in the depths of some secluded dell, or under the shelter of some dark leafy bank of verdure.”

Images

Inscribed

John or William Bartram, "A Draught of John Bartram’s House and Garden as it appears from the River", 1758.

Pierre Pharoux, “General Map of the honorable Wm. frederic Baron of Steuben’s Mannor”, c. 1793.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Sketch of the Estate of Henry Banks Esqr. on York River, March 1797. “Mill Pond 3 Miles long” describes the pond at the top of the image.

Anonymous, “Barrell Farm,” Pleasant Hill, 1817. A “fish pond” is situated near the Poplar Grove.

J. C. Loudon, “Ponds or large basins” and “Tanks or cisterns,” in An Encyclopædia of Gardening, 4th ed. (1826), 339, figs. 286–88.

J. C. Loudon, A garden in the ancient style, in An Encyclopaedia of Gardening, 4th ed. (1826), 1009, fig. 694.

Alexander Wadsworth, “Plan of Mount Auburn,” November 1831.

Anonymous, “Mount Auburn,” in American Magazine of Useful and Entertaining Knowledge 1, no. 10 (June 1835): 450.

Anonymous, “Forest Pond,” in The Picturesque Pocket Companion, and Visitor’s Guide, through Mount Auburn (1839), 171.

Anonymous, “Garden Pond,” in The Picturesque Pocket Companion, and Visitor’s Guide, through Mount Auburn (1839), 85.

James Smillie, “Greenwood Cemetery,” in Nehemiah Cleaveland, Green-Wood Illustrated (1847), flyleaf.

Thomas S. Sinclair, “Plan of the Pleasure Grounds and Farm of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane at Philadelphia,” in Thomas S. Kirkbride, American Journal of Insanity 4, no. 4 (April 1848): pl. opp. 280. The pond is labelled as "15".

Anonymous, “Plan of a Mansion Residence, laid out in the natural style,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (1849), 115, fig. 25.

James Smillie, “Mount Auburn Cemetery,” in Cornelia W. Walter, Mount Auburn Illustrated (1847; repr., 1850), frontispiece.

James Smillie (artist), John A. Rolph (engraver), “Forest Pond, Mount Auburn Cemetery,” in Cornelia W. Walter, Mount Auburn Illustrated (1847; repr., 1850), opp. 94.

Associated

Sydney L. Smith (engraver) from a watercolor drawing by Christian Remick (c. 1768) . A Prospective View of part of the Commons, 1902. Boston Pictorial Archive, Boston Public Library.

William Russell Birch, “View from the Elysian Bower, Springland, Pennsylvna the residence of Mr W. Birch,” 1808, in William Russell Birch and Emily Cooperman, The Country Seats of the United States (2009), 81, pl. 20.

Anonymous, “View of Mount Auburn,” in American Magazine of Useful and Entertaining Knowledge 2, no. 6 (February 1836): 234. The walk wraps alongside the pond in the center of the image.

John Notman, Plan of Hollywood Cemetery, 1848.

James Smillie, “View of the Consecration Dell, Mount Auburn Cemetery,” in Cornelia W. Walter, Mount Auburn Illustrated (1847; repr., 1850), opp. 100.

Alexander Jackson Davis, Blithewood looking towards Montgomery Place, n.d. The Alexander Jackson Davis Sketchbook, c. 1830–50.

Attributed

Charles Fraser, Another View of the Same (Ashley Hall), 1803.

Joseph Jacques Ramée (artist), J. Klein and V. Balch (engravers), “View of Union College in the City of Schenectady,” c. 1820.

Thomas Chambers, Mount Auburn Cemetery, mid-19th century.

Notes

- ↑ Noah Webster, “Pool” entry, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), 2:n.p., view on Zotero.

- ↑ A cistern generally referred to a receptacle built to collect and retain water, either from a stream, spring, or rainfall. Similar receptacles that collected ground water were called wells. Both cisterns and wells, ubiquitous features, were sometimes incorporated into landscape designs by placing them at intersections of walks or by ornamenting them with well heads, plantings, or other decorative treatments.

- ↑ A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 4th ed. (New York: G. P. Putnam, 1849), 347–67, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Downing 1849, 366–67, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Dowing 1849, 348, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Eliza Lucas Pinckney, The Letterbook of Eliza Lucas Pinckney, 1739–1762, ed. Elise Pinckney (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1972), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Pehr Kalm, The America of 1750: Peter Kalm’s Travels in North America. The English Version of 1770, 2 vols. (New York: Wilson-Erickson, 1937), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Loutrel Winslow Briggs, Charleston Gardens (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1951), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Parker Cutler, Life, Journals, and Correspondence of Rev. Manasseh Cutler, LL.D. (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1987), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Bentley, The Diary of William Bentley, D.D., Pastor of the East Church, Salem, Massachusetts (Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1962), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Flowers, “People and Plants: North Carolina’s Garden History Revisited,” Eighteenth Century Life 8 (1983): 117–29, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Peter Martin, The Pleasure Gardens of Virginia: From Jamestown to Jefferson (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Lillian B. Miller et al., eds., The Selected Papers of Charles Willson Peale and His Family, vol. 3, The Belfield Farm Years, 1810–1820 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Therese O’Malley, “Art and Science in American Landscape Architecture: The National Mall, Washington, D.C. 1791–1852” (PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1989), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Lillian B. Miller et al., eds., The Selected Papers of Charles Willson Peale and His Family, vol. 5, The Autobiography of Charles Willson Peale (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Hebron Moore, “A View of Philadelphia in 1829: Selections from the Journal of B. L. C. Wailes of Natchez,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 78 (July 1954): 353–60, view on Zotero.

- ↑ James Boyd, A History of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1827–1927 (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1929), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Malthus A. Ward, An Address Pronounced Before the Massachusetts Horticultural Society (Boston: J. T. & E. Buckingham, 1831), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thaddeus William Harris, A Discourse Delivered before the Massachusetts Horticultural Society on the Celebration of Its Fourth Anniversary, October 3, 1832 (Cambridge, MA: E. W. Metcalf, 1832), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Martha Ogle Forman, Plantation Life at Rose Hill: The Diaries of Martha Ogle Forman, 1814-1845 (Wilmington, Del.: Historical Society of Delaware, 1976), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, The Picturesque Pocket Companion and Visitor’s Guide through Mount Auburn (Boston: Otis, Broader, 1839), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Mason Hovey, “Notices of Gardens and Horticulture, in Salem, Mass.,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 5, no. 11 (November 1839): 401–16, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Nehemiah Adams, Boston Common (Boston: William D. Ticknor and H. B. Williams, 1842), view on Zotero.

- ↑ W., “An Account of the Lowell Cemetery, Its Situation, Historical Associations, and Particular Description,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 8, no. 2 (February 1842): 47–50, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Catherine Evans, Cultural Landscape Report for Longfellow National Historic Site, History and Existing Conditions (Boston: National Park Service, North Atlantic Region, 1993), view on Zotero.

- ↑ P. B., “Progress of Horticulture in Rochester, N.Y.,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 10, no. 1 (January 1844): 15–19, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Nehemiah Cleaveland, Green-Wood Illustrated (New York: R. Martin, 1847), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Constance Greiff, John Notman, Architect, 1810–1865 (Philadelphia: Athenaeum of Philadelphia, 1979), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas S. Kirkbride, “Description of the Pleasure Grounds and Farm of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, with Remarks,” American Journal of Insanity 4, no. 4 (April 1848): 347–54, view on Zotero.

- ↑ C. M. Hovey, “Notes on Gardens and Nurseries,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 16, no. 10 (October 1850): 461–62, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Wilcomb E. Washburn, “Vision of Life for the Mall,” AIA Journal 47 (1967): 52–59, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language: In Which the Words Are Deduced from the Originals and Illustrated in the Different Significations by Examples from the Best Writers, 2 vols. (London: W. Strahan for J. and P. Knapton, 1755), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Hale, A Compleat Body of Husbandry Containing Rules for Performing, in the Most Profitable Manner, the Whole Business of the Farmer and Country Gentleman, 2nd ed., 4 vols. (London: T. Osborne, 1758), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel Deane, The New-England Farmer, or Georgical Dictionary (Worcester, MA: Isaiah Thomas, 1790), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, Encyclopaedia, or A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Miscellaneous Literature, 18 vols. (Philadelphia: Thomas Dobson, 1798), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Abercrombie, Abercrombie’s Practical Gardener Or, Improved System of Modern Horticulture (London: T. Cadell and W. Davies, 1817), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, 4th ed. (London: Longman et al., 1826), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Zebedee Cook Jr., An Address, Pronounced before the Massachusetts Horticultural Society (Boston: Isaac R. Butts, 1830), view on Zotero.

- ↑ James E. Teschemacher, “On Horticultural Architecture,” Horticultural Register, and Gardener’s Magazine 1 (May 1, 1835): 157–61, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Edward Sayers, “On Laying out Gardens and Ornamental Plantations,” Horticultural Register, and Gardener’s Magazine 3 (November 1, 1837): 409–11, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Edward Sayers, The American Flower Garden Companion, Adapted to the Northern States (Boston: Joseph Breck and Company, 1838), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Robert Buist, The American Flower Garden Directory, 2nd ed. (Philadelphia: Carey and Hart, 1841), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jane Loudon, Gardening for Ladies; and Companion to the Flower-Garden, ed. A. J. Downing (New York: Wiley & Putnam, 1845), view on Zotero.

- ↑ George William Johnson, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening, ed. David Landreth (Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1847), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Wyllys Elliott, “Reviews: Cottages and Cottage Life,” The Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 3, no. 4 (October 1848): 179–82, view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America, 4th ed. (1849; repr., Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. Downing, “Domestic Notices: Making Fish Ponds,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 6, no. 1 (January 1851): 53–54, view on Zotero.

- ↑ R. B. L., “On Artificial Rockeries,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 6, no. 6 (June 1851): 276–79, view on Zotero.