Difference between revisions of "Fountain"

V-Federici (talk | contribs) m (→Inscribed) |

|||

| (227 intermediate revisions by 10 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

| − | [[ | + | Numerous European treatises stressed the fountain as a principal ornament of the garden. Its popularity was attested to by its frequent use in both European and American gardens.<ref>For histories of European fountains, see Bertha Harris Wiles, ''The Fountains of Florentine Sculptors and Their Followers from Donatello to Bernini'' (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1933), and Elisabeth B. MacDougall, ed., ''Fons Sapientiae: Renaissance Garden Fountains'' (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks, 1978), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/RJJ9ZNJ8 view on Zotero]. For information on European grotto fountains and their hydraulics, see Naomi Miller, ''Heavenly Caves: Reflections on the Garden Grotto'' (New York: G. Braziller, 1982), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/CCH54F54 view on Zotero].</ref> Hydraulics (the branch of engineering concerned with moving water), however, did not play a major role in American garden design until the late 18th century, despite the frequent mention of still-water features such as [[canal|canals]], [[pond|ponds]], and pools in garden descriptions. In spite of the rarity of early examples that were executed, the term “fountain” was utilized and was understood to describe a variety of devices that issued water under pressure. This pressure was generated by gravity from an elevated water source—by a pump, or, later, by municipal pressurized water systems. Water, conveyed in pipes, was forced through an aperture that determined the trajectory of the spray. As George William Johnson (1847) and [[Jane Loudon]] (1845) described the process, different orifices could project water horizontally, vertically, or in an arc, enabling the designer to create effects simulating the form of a sheaf, fan, dome, or basket. A fountain with a single spout of water was sometimes called by its French synonym, ''[[jet|jet d’eau]]'', but larger waterworks, such as those in public [[square|squares]] and [[park|parks]], were generally referred to as fountains (see [[Jet]]). |

| − | + | Although the research presented here has not revealed any work originating in the colonies, fountain technology was published in 18th-century European sources available in America, such as Stephen Switzer’s ''An Introduction to a General System of Hydrostaticks and Hydraulicks, Philosophical and Practical'' (1729). More widely available treatises discussed the role of fountains in garden design, but they do not include the level of detail and technical information found in Switzer. [[Andrew Jackson Downing|A. J. Downing's]] ''A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening'' (1849) was the first American source to present an illustrated typology of fountains (such as weeping, or “Tazza” fountains, [[rockwork]], and candelabra [[jet|jets]]), but for further terminology and instruction, Downing directed the reader to “numerous French works devoted to this branch of Rural Embellishment.”<ref>A. J. Downing, ''A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening'', 4th ed. (1849; repr. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1991), 471, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/K7BRCDC5 view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | on the | ||

| − | |||

| − | [[File:0483.jpg|thumb| | + | [[File:0483.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 1, Anonymous, ''Croton Water Celebration 1842'', 1842.]] |

| − | + | The chronology of fountain construction in American gardens contrasts markedly with that of European and British practice. The only two known references to fountains from the 18th century are <span id="Byrd_cite"></span>William Byrd II's 1732 account of the fountain at Col. Alexander Spotswood’s estate, near Germanna, Virginia ([[#Byrd|view text]]), and <span id="Thacher_cite"></span>James Thacher’s 1830 recollections of a visit some 42 years earlier to Col. Thaddeus Kosciusko’s garden at West Point, New York ([[#Thacher|view text]]). Even in the early 19th century, fountains in private gardens like the one built in 1814 at [[Belfield]], [[Charles Willson Peale|Charles Willson Peale's]] estate in Germantown, Pennsylvania, were rare. Public fountains appeared in descriptions near the turn of the 19th century, with the earliest examples in public [[pleasure ground|pleasure grounds]], such as Columbia and Mount Vernon Gardens in New York. Plans made in 1792 for Washington, DC, by [[Pierre-Charles L’Enfant]] included fountains at the intersections of prominent [[avenue|avenues]], but these were not executed until the second half of the 19th century, following the installation of a city water system.<ref>National Capital Planning Commission, ''Worthy of the Nation: The History of Planning for the National Capital'' (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1977), 56, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/8SBVDIEF view on Zotero].</ref> It was only after the introduction of city water systems in the 1820s through the 1840s that such public fountains became common, like the one in Springfield, Massachusetts.<ref>Gloria Gilda Deák, ''Picturing America: Prints, Maps, and Drawings Bearing on the New World Discoveries and on the Development of the Territory that is now the United States, 1497–1899'', 2 vols. (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1988), 1:349, 384, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/4A6QNFNX view on Zotero]. For a discussion of the broader history of urban water systems, see Nelson M. Blake, ''Water for Our Cities: A History of the Urban Water Supply Problem in the United States'' (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1956), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/8NTF9X77 view on Zotero].</ref> In New York, numerous paintings and prints, such as a print depicting City Hall Park [Fig. 1], captured the enthusiasm reported by Philip Hone (c. 1828–51) when he said, “Nothing is talked of or thought of in New York. . . but Croton water.” Not only did pressurized water make more elaborate hydraulics possible, but the celebration of civic pride, the advancement of “modern” technology, and the health and sanitation improvements associated with these water displays helped to justify the increased tax burden on citizens. | |

| − | + | [[File:0478.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 2, Benjamin Franklin Smith Jr., ''[[View]] of the Water Celebration, on [[Boston Common]] October 25<sup>th</sup> 1848'', 1849.]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[File: | + | [[File:1202.jpg|thumb||Fig. 3, Frederick Graff, Design for the ''Boy and Dolphin'' Fountain, Fairmount Waterworks, 1829.]] |

| − | [[ | + | American fountains varied in scale from a single spout of water, such as the [[jet]] rising from a still-water [[basin]] at [[Belfield]], to the large civic sponsored displays of City Hall Park and Union Square in New York, and the Cochituate Fountain on [[Boston Common]] [Fig. 2]. Following European design tradition, the apertures of fountains were sometimes incorporated into sculpture, often in the form of figures associated with water, such as the mythical form of a Naiad, which was praised by Mark Twain (1853) for spouting water at the Fairmount Waterworks in Philadelphia. Frederick Graff’s design of a “Boy and Dolphin” fountain, which was installed there in 1832, employed an ancient symbol of navigation safety [Fig. 3].<ref>Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, ''William Rush, American Sculptor'' (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 1982), 182, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/MDTB9JXT view on Zotero].</ref> One of the best-known examples of American fountain sculpture is William Rush’s [[statue]] “Water Nymph with Bittern,” which issued multiple [[jet|jets]] in front of Philadelphia’s first pumping station at Centre Square.<ref>For a discussion of Rush’s sculpture, see D. Dodge Thompson, “The Public Work of William Rush: A Case Study in the Origins of American Sculpture,” in ''William Rush, American Sculptor'' (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, 1982), 35–37, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/JF8XI3BT view on Zotero]. For a discussion of Krimmel’s view, see Anneliese Harding, ''John Lewis Krimmel: Genre Artist of the Early Republic'' (Winterthur, DE: Winterthur Publications, 1994), 22–23, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/4S877V88 view on Zotero].</ref> In less elaborate examples, water came forth from [[urn|urns]], multi-tiered [[basin|basins]], and, as at W. H. Corcoran’s garden in Washington, DC, described in 1846, the [[rockery]] (see [[Statue]]). |

| − | [[File: | + | [[File:0521.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 4, William Rush, ''North East or Franklin Public [[Square]], Philadelphia'', 1824.]] |

| − | + | The aesthetic appeal of garden fountains is evident in treatise literature, and this quality was often echoed and appreciated in descriptions of American fountains, such as in Lewis Miller’s poem and illustration of a fountain, both from his ''Orbis Pictus'' (c. 1850) [<span id="Fig_14_cite"></span>[[#Fig_14|See Fig. 14]]]. Depending upon its design, a fountain could add stateliness to a [[flower garden]] or a rustic naturalness to a [[rockery]]. Fountains of a “highly artificial” character, to quote [[A. J. Downing|Downing]], lent themselves to marking the intersection of paths or the end of [[walk|walks]] in much the same way as did [[obelisk|obelisks]], [[statue|statues]], or other architectural elements. William Rush’s 1824 design for Franklin Public [[Square]] in Philadelphia [Fig. 4] called for a central fountain in which the single [[jet]] of water cascaded down a pile of rocks similar to the base of his “Water Nymph and Bittern.”<ref>The plan was not executed until 1836, after Rush’s death, at which time a marble fountain not of Rush’s design, was installed. See Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts 1982, 167–68, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/MDTB9JXT view on Zotero].</ref> [[Robert Mills|Robert Mills's]] proposal for the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC (1841), shows two aligned fountains anchoring the central axis of the building and garden in the midst of the curvilinear [[walk|walks]] and planting [[bed|beds]] [<span id="Fig_12_cite"></span>[[#Fig_12|See Fig. 12]]]. As Charles Marshall (1799) noted, fountains cooled and refreshed through evaporation, and enhanced the aesthetic experience with the pleasant sounds and the animation of moving water. <span id="Johnson_cite"></span>George William Johnson’s ''A Dictionary of Modern Gardening'' (1847) pointed out the visual interest of the height of the water stream as the “surprise” and “novelty” of fountains ([[#Johnson|view text]]). Like other water features, fountains also combined the garden’s essential material of nature and art. Fountains joined the “natural” element of water with the artifice of plumbing, [[statue|statuary]], and the design of patterned streams. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | [[File:0438.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 5, Anonymous, ''Leaving the Manor House'', c. 1850–55.]] | |

| − | + | [[File:2283.jpg|thumb|Fig. 6, Anonymous (artist), Nathaniel Currier (lithographer), ''[[View]] of the Great Conflagration at New York July 19th 1845'', 1845.]] | |

| − | -- ''Elizabeth Kryder-Reid'' | + | In addition to their aesthetic appeal, fountains also conveyed the owner’s investment in an expensive water system and the specialized knowledge required to execute such a project. As obvious markers of wealth and status, fountains were often placed in prominent parts of a garden or in the center of the formal approach to a house or building, as in the painting ''Leaving the Manor House'' (c. 1850) [Fig. 5]. More symbolically, fountains were connected to the religious rites of baptism and renewal. A Shaker manuscript provided information to construct a fountain at New Lebanon, Ohio, as part of the community feast ground and to represent a “holy Fountain of waters of everlasting life” for the refreshment and purification of community members and for their reflection about heaven’s order on earth.<ref>Sally M. Promey, ''Spiritual Spectacles: Vision and Image in Mid-Nineteenth-Century Shakerism'' (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993), 77, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/JMPTCMS8 view on Zotero].</ref> Finally, fountains also served two vital practical functions. City fountains, such as the one depicted in a [[view]] of the Great Conflagration (1845) at New York, provided a water source for fighting urban fires [Fig. 6]; others, such as [[Robert Mills|Robert Mills's]] design for the [[national Mall]] in Washington, DC, provided water for irrigation. |

| + | |||

| + | —''Elizabeth Kryder-Reid'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | <hr> | ||

==Texts== | ==Texts== | ||

| − | |||

===Usage=== | ===Usage=== | ||

| − | * | + | *<div id="Byrd"></div>Byrd, William, II, September 28, 1732, describing the estate of Col. Alexander Spotswood, near Germanna, VA (1901; repr., 1970: 360)<ref>William Byrd, ''The Writings of Colonel William Byrd of Westover in Virginia, Esqr.'', ed. John Spencer Bassett (New York: B. Franklin, 1970), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/3VVVZ9XQ view on Zotero].</ref> |

| − | + | :“The afternoon was devoted to the ladys, who shew’d me one of their most beautiful [[Walk|Walks]]. They conducted me thro’ a Shady Lane to the Landing, and by the way made me drink some very fine Water that issued from a Marble '''Fountain''', and ran incessantly.” [[#Byrd_cite|back up to History]] | |

| − | :“The afternoon was devoted to the ladys, who | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | *[[ | + | *[[Pierre-Charles L’Enfant|L’Enfant, Pierre-Charles]], January 4, 1792, from notes on “Plan of the City,” describing Washington, DC (quoted in Caemmerer 1950: 164)<ref>H. Paul Caemmerer, ''The Life of Pierre-Charles L’Enfant, Planner of the City Beautiful, The City of Washington'' (Washington, DC: National Republic Publishing Company, 1950), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/PHWTAERT view on Zotero].</ref> |

| + | :“E. Five grand '''fountains''' intended with a constant spout of water. N. B. There are within the limits of the City above 25 good springs of excellent water abundantly supplied in the driest season of the year.” | ||

| − | |||

| + | [[File:0612.jpg|thumb|Fig. 7, John Bachmann, ''Bird’s Eye [[View]] of Boston'', c. 1850.]] | ||

| + | *[[Timothy Dwight|Dwight, Timothy]], 1796, describing Boston, MA (1821: 1:490–91)<ref>Timothy Dwight, ''Travels; in New-England and New-York'', 4 vols. (New Haven: The Author, 1821), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/VHBP7TH2 view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“It is remarkable, that the scheme of forming public [[square]]s, so beautiful, and in great towns so conducive to health, should have been almost universally forgotten. . . . On these open grounds the inhabitants might always find sweet air, charming [[walk]]s, '''fountains''' refreshing the atmosphere, trees excluding the sun, and, together with fine flowering [[shrub]]s, presenting to the eye the most ornamental objects, found in the country.” [Fig. 7] | ||

| − | |||

| − | : | + | *Bentley, William, September 4, 1798, describing the brewery of General Hull, Watertown, MA (1962: 2:280)<ref>William Bentley, ''The Diary of William Bentley, D.D., Pastor of the East Church, Salem, Massachusetts'' 4 vols. (Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1962), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/B63ABACF view on Zotero].</ref> |

| + | :“4. . . He is now erecting a ''brewery'' upon the river & has finished the great Building 120 feet by 42. It is 27 feet to the e[a]ves, & under the side of an hill so that the aquaduct from the surface enters at the second story. . . His Aquaduct is led a mile from a western hill & is carried in every form round his House built with Brick. It supplies the '''fountains''' in front of the house, the cold [[Bath]], the Barn [[yard]]s, the gardens, & at different distances in the fields may be unstopped for use.” | ||

| − | *[[ | + | [[File:0044.jpg|thumb|Fig. 8, [[Charles Willson Peale]], ''[[View]] of the garden at [[Belfield]]'', 1816.]] |

| + | *[[Charles Willson Peale|Peale, Charles Willson]], September 6, 1814, in a letter to his son, Rembrandt Peale, describing [[Belfield]], estate of [[Charles Willson Peale]], Germantown, PA (Miller et al., eds., 1991: 3:263)<ref>Lillian B. Miller et al., eds., ''The Selected Papers of Charles Willson Peale and His Family'', vol. 3, ''The Belfield Farm Years, 1810–1820'' (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1991), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/IZAKPCBG view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“I have finished my '''fountain''' and. . . the [[basin|Bason]] holds the water after much labour to make so having raised the Fish-[[pond]] it gives a [[jet]] of 12 feet high. . . Rubens has place all his [[Pot]]s round the '''fountain''' [[basin|B[a]son]] and it makes a very handsome display, The [[basin|Bason]] being 13 feet long & 10 wide.” [Fig. 8] | ||

| − | |||

| + | *Silliman, Benjamin, 1824, describing the mineral spring in New Lebanon, NY (1824: 46–47)<ref>Benjamin Silliman, ''Remarks Made on a Short Tour between Hartford and Quebec, in the Autumn of 1819'' (New Haven, CT: S. Converse, 1824), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/B5VWTWM5 view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“This is a very remarkable '''fountain'''. Unlike most mineral waters, it issues from a high hill; the water boils up in a space of ten feet wide, by three and a half deep. . . the water discharged amounts to eighteen barrels in a minute, and not only supplies the [[bath]]s very copiously, simply by running down hill to them.” | ||

| − | |||

| − | : | + | [[File:0484.jpg|thumb|Fig. 9, John Bachmann, ''New York City Hall, [[Park]] and Environs'', c. 1849.]] |

| + | *Hone, Philip, c. 1828–51, describing New York, NY (quoted in Deák 1988: 1:349)<ref>Gloria Gilda Deák, ''Picturing America, 1497–1899: Prints, Maps, and Drawings Bearing on the New World Discoveries and on the Development of the Territory That Is Now the United States'', 2 vols. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1988), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/4A6QNFNX view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“Nothing is talked of or thought of in New York. . . but Croton water; '''fountains''', aqueducts, hydrants, and hose attract our attention and impede our progress through the streets. Political spouting has given place to waterspouts, and the free current of water has diverted the attention of the people from the vexed questions of the confused state of the national currency. It is astonishing how popular the introduction of water is among all classes of our citizens, and how cheerfully they acquiesce in the enormous expense which will burden them and their posterity with taxes to the latest generation. Water! water! is the universal note which is sounded through every part of the city, and infuses joy and exultation into the masses, even though they are somewhat out of spirits.” [Fig. 9] | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Wailes, Benjamin L. C., December 29, 1829, describing [[Lemon Hill]], estate of [[Henry Pratt]], Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Moore 1954: 359)<ref name="Moore 1954">John Hebron Moore, “A View of Philadelphia in 1829: Selections from the Journal of B. L. C. Wailes of Natchez,” ''Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography'' 78 (July 1954): 353–60, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/Z9IBV7A4 view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| + | :“But the most enchanting [[prospect]] is towards the grand pleasure [[grove]] & [[green house]] of a Mr. Prat[t], a gentleman of fortune, and to this we next proceeded by a circutous [''sic''] rout, passing in [[view]] of the fish [[pond]]s, [[bower]]s, [[rustic style|rustic]] retreats, [[summer house]]s, '''fountains''', [[grotto]], &c., &c. The [[grotto]] is dug in a bank [and] is of a circular form, the side built up of rock and arched over head, and a number of Shells [?]. A dog of natural size carved out of marble sits just within the entrance, the guardian of the place. A narrow aperture lined with a [[hedge]] of [[arbor]] vitae leads to it. Next is a round fish [[pond]] with a small '''fountain''' playing in the [[pond]].” | ||

| − | |||

| − | :“There are also several pretty marble '''fountains''' in different parts of the city, which greatly add to its beauty. These are not, it is true, quite so splendid as that of the Innocents, or many others at Paris, but they are '''fountains''' of clear water, and they are built of white marble. There is one which is sheltered from the sun by a roof supported by light [[column]]s; it looks like a [[temple]] dedicated to the genius of the spring. The water flows into a marble cistern, to which you descend by a flight of steps of delicate whiteness, and return by another.” | + | *Trollope, Frances Milton, 1830, describing Baltimore, MD (1832: 1:292)<ref>Frances Trollope, ''Domestic Manners of the Americans'', 3rd ed., 2 vols. (London: Wittaker, Treacher, 1832), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/T5RXDF7G view on Zotero].</ref> |

| + | :“There are also several pretty marble '''fountains''' in different parts of the city, which greatly add to its beauty. These are not, it is true, quite so splendid as that of the Innocents, or many others at Paris, but they are '''fountains''' of clear water, and they are built of white marble. There is one which is sheltered from the sun by a roof supported by light [[column]]s; it looks like a [[temple]] dedicated to the genius of the spring. The water flows into a marble cistern, to which you descend by a flight of steps of delicate whiteness, and return by another.” | ||

| − | * | + | *<div id="Thacher"></div>Thacher, James, November 26, 1830, “An Excursion on the Hudson,” describing the garden of Col. Thaddeus Kosciusko, West Point, NY (''New England Farmer'' 9: 148),<ref> James Thacher, “An Excursion on the Hudson. Letter I,” ''New England Farmer, and Horticultural Journal'' 9, no. 19 (November 26, 1830): 148–49, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/VPTGX2EQ view on Zotero].</ref> |

| + | :“Among the interesting recollections pertaining to West Point is Kosciusko’s garden, situated in a deep rocky valley near the river, where in 1778, I was amused in viewing his curious water '''fountain''', spouting [[jet]]s and [[cascade]]s.” [[#Thacher_cite|back up to History]] | ||

| − | |||

| + | *Anonymous, May 9, 1831, describing Columbia Garden, New York, NY (''New York Evening Post'') | ||

| + | :“The Garden is beautifully shaded by a [[grove]] of trees, in the center of which is erected a '''FOUNTAIN''' of Italian Marble, which Mr. P. had executed in Italy, as a specimen of their style.” | ||

| − | |||

| − | : | + | [[File:1826.jpg|thumb|Fig. 10, [[J. C. Loudon]], Fountain supplied from a cistern, in ''The Suburban Gardener'' (1838), 582, fig. 233.]] |

| + | *Alcott, William A., 1838, “Embellishment and Improvement of Towns and Villages” (''American Annals of Education'' 8: 342)<ref>William A. Alcott, “Embellishment and Improvement of Towns and Villages,” ''American Annals of Education'' 8, no. 8 (August 1838): 337–47, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/5K3WRQ2I view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“It is in vain ever to expect the tone of mind or heart to be, as a general fact, so elevated under the deteriorating and withering influences of the half spoiled air, where there are nothing but huge [[wall]]s of brick and stone, thickly lining narrow streets, with no gardens and shade trees, as under the influence of pure air, and in the midst of gardens, and [[common]]s, and fields, and '''fountains''', and shade trees, and [[shrubbery]].” | ||

| − | *[[ | + | *[[J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon|Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius)]], 1838, describing the Lawrencian Villa, residence of Mrs. Lawrence, Drayton Green, near London, England (1838: 582) |

| + | :“At the point 15, we are immediately in front of the '''fountain'''. . . supplied from a cistern which forms a small tower on the top of the tool-house; and beyond that is a [[walk]] to the stone cistern at 16, which supplies water for watering the garden. The water is raised to these cisterns by a forcing pump in the stableyard.” [Fig. 10] | ||

| − | |||

| + | *Willis, Nathaniel Parker, 1840, describing Undercliff, seat of Gen. George P. Morris, near Cold-Spring, NY (1840; repr., 1971: 2: 233)<ref name="Willis 1971">Nathaniel Parker Willis, ''American Scenery, or Land, Lake and River Illustrations of Transatlantic Nature'', 2 vols. (Barre, MA: Imprint Society, 1971), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/T5CMW67U view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“In front, a circle of greensward is refreshed by a '''fountain''' in the centre, gushing from a Grecian [[vase]], and encircled by ornamental [[shrubbery]]; from thence a gravelled [[walk]] winds down a gentle declivity to a second plateau, and again descends to the entrance of the carriage road, which leads upwards along the left slope of the hill, through a noble forest, the growth of many years, until suddenly emerging from its sombre shades, the visitor beholds the mansion before him in the bright blaze of day.” | ||

| − | |||

| − | : | + | [[File:1120.jpg|thumb|Fig. 11, W. H. Bartlett, “Fairmount Gardens, with the Schuylkill Bridge,” in Nathaniel Parker Willis, ''American Scenery'', 2 vols. (1840), vol. 2, pl. 24.]] |

| + | *Willis, Nathaniel Parker, 1840, describing the Fairmount Waterworks, Philadelphia, PA (1840; repr., 1971: 2:313)<ref name="Willis 1971"></ref> | ||

| + | :“Steps and [[terrace|terrace]]s conduct to the reservoirs, and thence the [[view]] over the ornamented grounds of the country [[seat]]s opposite, and of a very [[picturesque]] and uneven country beyond, is exceedingly attractive. Below, the court of the principal building is laid out with gravel [[walk]]s, and ornamented with '''fountains''' and flowering trees; and within the edifice there is a public drawing-room, of neat design and furniture; while in another wing are elegant refreshment-rooms—and, in short, all the appliances and means of a place of public amusement.” [Fig. 11] | ||

| − | * | + | *Buckingham, James Silk, April 1840, describing the garden of Father George Rapp, Economy, PA (1842: 2:227)<ref>James Silk Buckingham, ''The Eastern and Western States of America'', 3 vols. (London: Fisher, 1842), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/FFXTKXCI/ view on Zotero].</ref> |

| + | :“This [the garden] covered about an acre and half of ground, and was neatly laid out in [[lawn]]s, [[arbor|arbours]], and flower-[[bed]]s, with two prettily ornamented open octagonal [[arcade]]s, each supporting a circular dome over a '''fountain'''.” | ||

| − | |||

| + | *Buckingham, James Silk, 1841, describing Baltimore, MD (1841: 1:280–81)<ref name="Buckingham_1841">James Silk Buckingham, ''America, Historical, Statistic, and Descriptive'', 2 vols. (New York: Harper, 1841), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/PIANFMVK view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“There are several springs or '''fountains''' in different parts of the city, which add to its beauty and convenience. The City Spring is enclosed by an iron railing, and covered by a dome supported by [[pillar]]s; it is surrounded by trees and foliage, and has a very pleasing effect. The Western '''Fountain''', in another [[quarter]] of the town, is also covered with a dome supported by [[column]]s, and is used for the supply of ships in the harbour of Baltimore with water. The Eastern '''Fountain''' is much larger, and adorned with more of architectural beauty. It has an Ionic colonnade, open all around, supporting a roof over the spring, which is enclosed within iron railings. The Centre '''Fountain''', in front of the market, is also an ornament to the spot. The markets are excellent structures, and well adapted to their several uses. | ||

| + | :“It is to be regretted that the introduction of '''fountains''' is not more frequent in the cities of England and America. Whoever has travelled much in Turkey, Greece, Italy, Spain, and Portugal, cannot fail to have admired the many beautiful '''fountains''' adorning the open places and public [[square]]s of the ancient cities of these countries. The refreshing coolness of the atmosphere, the sparkling brilliance of the waters, the soothing murmur of their falling sounds, and the air of freshness, luxury, and repose, which are all sources of enjoyment, are in themselves sufficient recommendation. It seems astonishing that London, Edinburgh, and Dublin, as well as New-York, Philadelphia, and Washington, should be do deficient as they are in these combinations of beauty and utility.” | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | *Buckingham, James Silk, 1841, describing Saratoga Springs, NY (1841: 2:102)<ref name="Buckingham_1841"></ref> | ||

:“From daylight, therefore, until seven o’clock in the morning, the well or '''fountain''', which is enclosed beneath a roof supported by a colonnade of fluted wooden [[pillar]]s, is crowded with drinkers, and some are said to take the number of twenty tumblers of the water before breakfast.” | :“From daylight, therefore, until seven o’clock in the morning, the well or '''fountain''', which is enclosed beneath a roof supported by a colonnade of fluted wooden [[pillar]]s, is crowded with drinkers, and some are said to take the number of twenty tumblers of the water before breakfast.” | ||

| − | *[[Mills, Robert]], 23? | + | <div id="Fig_12"></div>[[File:0032.jpg|thumb|Fig. 12, [[Robert Mills]], ''[[Picturesque]] [[View]] of the Building, and Grounds in front'', 1841. [[#Fig_12_cite|Back up to history]]]] |

| + | *[[Robert Mills|Mills, Robert]], February 23?, 1841, in letter to Joel R. Poinsett, describing his design for the [[national Mall]], Washington, DC (Scott, ed., 1990: n.p.)<ref>Pamela Scott, ed., ''The Papers of Robert Mills'' (Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Resources, 1990), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/9CEBJWW8 view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“The main building for the Institution is located about 300 feet south of the [[wall]] fronting the [[Botanic garden]], from which it is separated by a circular road, in the centre of which is a '''fountain''' of water from the [[basin]] of which pipes are led underground thro’ the [[walk]]s of the garden, for irrigating the same at pleasure, the '''fountain''' may be supplied from the [[canal]] flowing near the north [[wall]] of inclosure.” [Fig. 12] | ||

| − | |||

| + | *Adams, Nehemiah, 1842, describing [[Boston Common]], Boston, MA (1842: 47–49)<ref>Nehemiah Adams, ''Boston Common'' (Boston: William D. Ticknor and H. B. Williams, 1842), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/VXTWGJ58 view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“Another illustration of the same kind is a recent proposition to conduct the rain water from the dome of the state-house into a central reservoir for the fire department, and to make the water show itself, on its way through the [[Boston Common|Common]], in [[jet]]s and '''fountains'''. . . | ||

| + | :“'''Fountains''' on the [[Boston Common|Common]] would contribute greatly to the happiness of the people, — to their health of body and mind. Individuals of a melancholy disposition, occasioned by sedentary employments, would do well to spend more time on the [[Boston Common|Common]], and especially to walk often by the Frog [[Pond]], and watch the boys and children at their sport. Many a troubled mind, which neither the physician nor the clergyman can comfort, would also be soothed by lingering around a playing '''fountain''', and seeing its vigorous, graceful stream mounting into the air, waving in the wind, and falling back into its [[bed]]. . . | ||

| + | :“the sight of playing '''fountains''' on the [[Boston Common|Common]], and of multitudes participating in the enjoyment of them, will both leave a soothing and refreshing influence, and stir the social, kind feelings of the people.” | ||

| − | |||

| − | : | + | <div id="Fig_13"></div>[[File:1239_detail.jpg|thumb|Fig. 13, George Washington Sully, ''View of the New Orleans River Front from Canal Street to the Place d’Armes'', 1836, detail. [[#Fig_13_cite|Back to Associated Images]]]] |

| − | + | *Hall, Abraham Oakley, 1846, describing the Place d’Armes (renamed Jackson Square), New Orleans, LA (quoted in Upton 1994: 283)<ref>Dell Upton, “The Master Street of the World, The Levee,” in ''Critical Perspectives on Public Space'', ed. Çelik Zeynep, Diane Favro, and Richard Ingersoll (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994), 277–88, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/VRIZJBEI view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | : | + | :“A very neat railing, one or two respectable aged trees, a hundred or two blades of grass, a dilapidated '''fountain''', a very naked flag-staff. . . It has a water [[view]], and with a judicious expenditure of a few thousand dollars might be made an inviting [[promenade]]; it is now but a species of cheap lodging-house for arriving emigrants, drunken sailors, and lazy stevedores.” [Fig. 13] |

| − | * | + | *Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), October 1845, “Notes of a Visit to Several Gardens in the Vicinity of Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York,” describing the garden of W. H. Corcoran, Washington, DC (''Magazine of Horticulture'' 12: 245)<ref>Charles Mason Hovey, “Notes of a Visit to Several Gardens in the Vicinity of Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York, in October, 1845,” ''Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs'' 12, no. 7 (July 1846): 241–48, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/S9UVTJM3 view on Zotero].</ref> |

| + | :“At one end of the garden, is a very neatly constructed [[Rockwork|rock work]], with a [[basin]] in the centre, supplied with water from a cistern placed at some distance, but which is only a few feet higher than the water. Small tubes project through the [[Rockwork|rock work]], and by turning a cock, the water is thrown up in several small [[jet]]s and falls into the [[basin]]. Such '''fountains''' are constructed at very little expense, and in small gardens they afford much gratification.” | ||

| − | |||

| + | *Cleaveland, Nehemiah, 1847, describing Green-Wood Cemetery, Brooklyn, NY (1847: vi)<ref>Nehemiah Cleaveland, ''Green-Wood Illustrated'' (New York: R. Martin, 1847), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/JXFI68UM/ view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“To preserve, at all times, the supply and the transparency of the smaller [[pond]]s—to facilitate the sprinkling of the roads, and the irrigation of the grounds during periods of drought and dust— and especially to enrich the scenery, already so lovely, with a perfecting charm, the unfailing water of Sylvan Lake has been lifted into an elevated reservoir. Distributing pipes have been laid, and the visiter of the coming season will be refreshed by the sparkling beauty and gentle murmur of '''fountain''' and stream.” | ||

| − | |||

| − | : | + | <div id="Fig_14"></div>[[File:0576.jpg|thumb|Fig. 14, Lewis Miller, “In beauteous Order Terminate the Scene. . . ,” in ''Orbis Pictus'' (c. 1849), 46. [[#Fig_14_cite|Back up to history]]]] |

| + | *Miller, Lewis, c. 1849, description on a drawing of an idealized scene in the ''Orbis Pictus'' (n.p.)<ref>Lewis Miller, ''Orbis Pictus: A Picturesque Album to the Ladies of York, Pennsylvania'' (Williamsburg, VA: Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1850), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/XNQR79ST view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“In beauteous Order Terminate the Scene. | ||

| + | :the plenteous '''fountain''' the whole [[prospect]] crowned; | ||

| + | :Around the Gar-den leads its Streams. | ||

| + | :Visits each plant, and waters the Ground; | ||

| + | :While that in pipes beneath flows, | ||

| + | :And thence its Current On the town bestows. | ||

| + | :To verious use [''sic'']. for washing and drink. | ||

| + | :the People Supplies.” [Fig. 14] | ||

| − | *[ | + | *Justicia [pseud.], March 1849, “A Visit to Springbrook,” seat of Caleb Cope, near Philadelphia, PA (''Horticulturist'' 3: 411)<ref>Justicia [pseud.], “A Visit to Springbrook, the Seat of the President of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society,” ''Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste'' 3, no. 9 (March 1849): 411–14, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/AAEZMA9A view on Zotero].</ref> |

| + | :“To the left of this [[grove]] is a sheet of spring water, rising on the farm, (which farm contains upwards of 100 acres,) that supplies a powerful ''Hydraulic Ram'', diffusing the water over the whole place, supplying reservoirs, '''fountains''', [[waterfall]]s, &c.” | ||

| − | |||

| + | [[File:1967.jpg|thumb|Fig. 15, [[A. J. Downing]], ''Plan Showing Proposed Method of Laying Out the [[Public garden/Public ground|Public Grounds]] at Washington'', 1851.]] | ||

| + | *[[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing, Andrew Jackson]], 1851, describing plans for improving the public grounds of Washington, DC (quoted in Washburn 1967: 55)<ref>Wilcomb E. Washburn, “Vision of Life for the Mall,” ''AIA Journal'' 47, no. 3 (March 1967): 52–59, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/TA59MHC7 view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“5th: '''Fountain''' [[Park]] | ||

| + | :“This [[Park]] would be chiefly remarkable for its water features. The '''Fountain''' would be supplied from a [[basin]] in the Capitol. The [[pond]] or [[lake]] might either be formed from the overflow of this '''fountain''', or from a filtering drain from the [[canal]]. The earth that would be excavated to form this [[pond]] is needed to fill up low places now existing in this portion of the grounds.” [Fig. 15] | ||

| − | |||

| − | : | + | *Twain, Mark, October 26, 1853, describing Fairmount Waterworks, Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Gibson 1988: 2)<ref>Jane Mork, “The Fairmount Waterworks,” ''Bulletin, Philadelphia Museum of Art'' 84, no. 360–61 (Summer 1988): 5–40, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/RZEZDDEN view on Zotero].</ref> |

| + | :“Seeing a [[park]] at the foot of the hill, I entered—and found it one of the nicest little places about. Fat marble Cupids, in big marble [[vase]]s, squirted water upward incessantly. Here stands in a kind of mausoleum, (is that proper?) a well executed piece of sculpture, with the inscription—‘Erected by the City Council of Philadelphia, to the memory of Peter [i.e. Frederick] Graff, the founder and inventor of the Fairmount Water Works.’ The bust looks toward the dam. It is all of the purest white marble. . . [T]here was a long flight of stairs, leading to the summit of the hill. I went up—of course. But I forgot to say, that at the foot of this hill a pretty white marble Naiad stands on a projecting rock, and this, I must say is the prettiest '''fountain''' I have seen lately. A nice half-inch [[jet]] of water is thrown straight up ten or twelve feet, and descends in a shower all over the fair water spirit. '''Fountains''' also gush out of the rock at her feet in every direction.” | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Citations=== | ===Citations=== | ||

| − | * | + | *Parkinson, John, 1629, ''Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris'' (1629, repr., 1975: 5)<ref>John Parkinson, ''Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris'' (Norwood, NJ: W. J. Johnson, 1975), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/7G5933QV view on Zotero].</ref> |

| + | :“For there may be therein [the garden]. . . a '''fountaine''' in the midst thereofto convey water to every part of the Garden.” | ||

| − | |||

| + | [[File:1055.jpg|thumb|Fig. 16, Michael van der Gucht, “Four Designs for Cloisters,” in A.-J. Dézallier d’Argenville, ''The Theory and Practice of Gardening'' (1712), pl. 9.]] | ||

| + | *Dezallier d’Argenville, Antoine-Joseph, 1712, ''The Theory and Practice of Gardening'' (1712: 74, 75–76)<ref>A.-J. (Antoine Joseph) Dézallier d’Argenville, ''The Theory and Practice of Gardening; Wherein Is Fully Handled All That Relates to Fine Gardens, . . . Containing Divers Plans, and General Dispositions of Gardens. . . ,'' trans. John James (London: Geo. James, 1712), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/RNT8ZVZ8 view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“'''FOUNTAINS''', next to Plants, are the principal Ornaments of Gardens: 'Tis these that seem to animate them, by the murmuring and spouting of their Waters, and produce those admirable Beauties, that the Eye is scarce ever satisfied with beholding them. . . | ||

| + | :“[[statue|STATUES]] and [[Vase]]s contribute very much to the Embellishment and Magnificence of a Garden, and extremely advance the natural Beauties of it. . . | ||

| + | :“THESE Figures represent all the several Deities, and illustrious Persons of Antiquity, which should be placed properly in Gardens, setting the River-Gods, as the ''Naiades'', ''Rivers'', and ''Tritons'', in the Middle of '''Fountains''' and [[basin|Basons]]; and those of the [[Wood]]s, as ''Sylvanes'', ''Faunes'', and ''Dryads'', in the [[Grove]]s.” [Fig. 16] | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Miller, Philip, 1733, ''The Gardeners Dictionary'' (1733: n.p.)<ref>Philip Miller, ''The Gardeners Dictionary: Containing the Methods of Cultivation and Improving the Kitchen, Fruit, and Flower Garden. As Also, the Physick Garden, Wilderness, Conservatory, and Vineyard. . . Interspers’d with the History of the Plants, the Characters of Each Genus and the Names of All the Particular Species, in Latin and English; and an Explanation of All the Terms Used in Botany and Gardening, Etc.'', 2nd ed. (London: Philip Miller, 1733), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/HN3GIUJC/ view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | : | + | :“Of Artificial '''''Fountains''''' there is a great Variety. . . they are not only great Ornaments to a fine Garden, but also of great Use. But they ought not be plac’d too near the House, by reason of the Vapours that arise from the Water, which may be apt to strike a Damp to the [[Wall]]s, and spoil the Paintings, &c. and the Summer Vapours may cause a Malignity in the Air, and so be prejudicial to the Health of the Family; and likewise the Noise may be incommodious in the Night. |

| − | + | :“'''''Fountains''''' in the Garden should be so distributed, that they may be seen almost all at one Time, and that the Water-spouts may range all in a Line one with another; which is the Beauty of them; for this occasions an agreeable Confusion to the Eye, making them appear to be more in Number than really they are. See ''[[jet|Jet d’Eau]]'', ''Springs'', ''Vapours'', ''Water'', ''&c''.” | |

| − | *[[ | + | *[[Ephraim Chambers|Chambers, Ephraim]], 1741, ''Cyclopaedia'' (1741: 1:n.p.)<ref>Ephraim Chambers, ''Cyclopaedia, or An Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences. . . . '', 5th ed., 2 vols. (London: D. Midwinter et al., 1741–43), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/PTXK378N view on Zotero].</ref> |

| − | + | :“AJUTAGE, or ADJUTAGE, in hydraulics, part of the apparatus of an artificial '''fountain''', or [[jet|jet d'eau]]; being a sort of tube, fitted to the mouth or aperture of the vessel: through which the water is to be played, and by it determined into this or that figure. . . | |

| − | [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/ | + | :“'''FOUNTAIN''', or ''artificial'' '''FOUNTAIN''', in hydraulicks, a machine, or contrivance, whereby the water is violently spouted, or darted up; called also ''[[jet|Jet d’Eau]]''. See ''[[jet|JET d’ Eau]]'', FLUID, ''&c''. |

| + | :“There are divers kinds of artificial '''''Fountains'''''; some founded on the spring, or elasticity of the air; and others on the pressure or weight of the water, ''&c''. | ||

| + | :“The chief furniture of [[pleasure garden|pleasure gardens]] are, [[parterre|parterres]], [[vista|vistas]], glades, [[grove|groves]], compartiments, quincunces, verdant halls, [[arbor|arbour]] work, mazes, [[labyrinth|labyrinths]], '''fountains''', cabinets, [[cascade|cascades]], [[canal|canals]], [[terrace|terraces]], ''&c''. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | *Johnson, Samuel, 1755, ''A Dictionary of the English Language'' (1755: 1:n.p.)<ref> Samuel Johnson, ''A Dictionary of the English Language: In Which the Words Are Deduced from the Originals and Illustrated in the Different Significations by Examples from the Best Writers'', 2 vols. (London: W. Strahan for J. and P. Knapton, 1755), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/GE2JPJR3 view on Zotero]. </ref> | ||

| + | :“FOUNT. ''n.s.'' [''fons'', Latin; ''fountaine'', French.] | ||

| + | :“'''FOUNTAIN'''. | ||

| + | :“1. A well; a spring. . . | ||

| + | :“2. A small [[basin|bason]] of springing water. . . | ||

| + | :“3. A [[jet]]; a spout of water.” | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Anonymous, 1798, ''Encyclopaedia'' (1798: 7:542)<ref>''Encyclopaedia, Encyclopaedia, or A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Miscellaneous Literature'', 18 vols. (Philadelphia: Thomas Dobson, 1798), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/F6T8DNDF view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“3dly, The next requisite is water; the want of which is one of the greatest inconveniences that can attend a garden, and will bring a certain mortality upon whatever is planted in it, especially in the greater droughts that often happen in a hot and dry situation in summer; besides its usefulness in fine gardens for making '''fountains''', [[canal]]s, [[cascade]]s, &c. which are the greatest ornaments of a garden.” | |

| − | : | ||

| − | |||

| − | * | + | *Marshall, Charles, 1799, ''An Introduction to the Knowledge and Practice of Gardening'' (1799: 1:123, 126)<ref>Charles Marshall, ''An Introduction to the Knowledge and Practice of Gardening'', 1st American ed., 2 vols. (Boston: Samuel Etheridge, 1799), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/DVB7T4I2 view on Zotero].</ref> |

| + | :“Gardens, were formerly loaded with [[statue]]s, and great improprieties were committed in placing them, as Neptune in a [[grove]], and Vulcan at a '''fountain''', large figures in small gardens, and small in large, &c. but, perhaps, works of the [[statue|statuary]] might still be introduced, and the meeting with ''Flora'', ''Ceres'', or ''Pomona'', &c. well executed, and in proper places, could hardly give offence. . . | ||

| + | :“''Water'' should only be introduced in full sight, where it will run itself ''clear''. . . Every ''spring'' of water should be made the most of, and though '''''fountains''''' ''[[jet|jet d'eau]]'': &c. are out of fashion, something of this kind is agreable enough. Near some piece of water, as a cool retreat, it is desirable that there should be something of the ''[[summerhouse|summer-house]]'' kind, and why not the simple rustic ''[[arbor|arbour]]'', embowered with the ''woodbine'', the ''sweetbriar'', the ''jasmine'', and the ''rose''?” | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | *[[Bernard M’Mahon|M’Mahon, Bernard]], 1806, ''The American Gardener’s Calendar'' (1806: 64–65)<ref>Bernard M’Mahon, ''The American Gardener’s Calendar: Adapted to the Climates and Seasons of the United States. Containing a Complete Account of All the Work Necessary to Be Done. . . for Every Month of the Year. . .'' (Philadelphia: Printed by B. Graves for the author, 1806), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/HU4JIS9C view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“In some spacious [[pleasure ground|pleasure-grounds]] various light ornamental buildings and erections are introduced, as ornaments to particular departments; such as [[temple]]s, [[bower]]s, banquetting houses, [[alcove]]s, [[grotto]]s, rural [[seat]]s, cottages, '''fountains''', [[obelisk]]s, [[statue]]s, and other edifices; these and the like are usually erected in the different parts, in openings between the divisions of the ground, and contiguous to the terminations of grand [[walk]]s, &c. . . | ||

| + | :“'''Fountains''' and [[statue]]s, are generally introduced in the middle of spacious opens. . . | ||

| + | :“Likewise in some parts are exhibited artificial [[rockwork|rock-work]], contiguous to some [[grotto]], '''fountain''', rural piece of water, &c. and planted with a variety of saxatile plants, or such as grow naturally on rocks and mountains.” | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | : | + | [[File:1336.jpg|thumb|Fig. 17, [[J. C. Loudon]], “Drooping fountains,” in ''An Encyclopædia of Gardening'' (1826), 359, figs. 341–43. ]] |

| + | *[[J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon|Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius)]], 1826, ''An Encyclopaedia of Gardening'' (1826: 358–59)<ref>J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, ''An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening'', 4th ed. (London: Longman et al., 1826), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/KNKTCA4W/ view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“1822. ''Of constructions for displaying water'', as an artificial decoration, the principal are [[cascade]]s, [[waterfall]]s, [[jet]]s, and '''fountains'''. . . | ||

| + | :“1832. ''Drooping '''fountains'''''. . . overflowing [[vase]]s, shells (as the chama gigas), cisterns, sarcophagi, dripping rocks, and [[rockwork]]s, are easily formed, requiring only the reservoir to be as high as the orifice whence the dip or descent proceeds. This description of '''fountains''', with a surrounding [[basin]], are peculiarly adapted for the growth of aquatic plants.” [Fig. 17] | ||

| − | *[[ | + | *[[Noah Webster|Webster, Noah]], 1828, ''An American Dictionary of the English Language'' (1828: 1:n.p.)<ref>Noah Webster, ''An American Dictionary of the English Language'', 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/N7BSU467 view on Zotero].</ref> |

| + | :“FOUNT', FOUNT'AIN, n. [L. ''fons''; Fr. ''fontaine''; Sp. ''fuente'', It. ''fonte'', ''fontana''; W. ''fynnon'', a '''fountain''' or source; ''fyniaw'', ''fynu'', to produce, to generate, to abound; ''fwn'', a source, breath, puff; ''fwnt'', produce.] | ||

| + | :“1. A spring, or source of water; properly, a spring or issuing of water from the earth. This word accords in sense with well, in our mother tongue; but we now distinguish them, applying '''''fountain''''' to a natural spring of water, and well to an artificial pit of water, issuing from the interior of the earth. | ||

| + | :“2. A small [[basin]] of springing water. ''Taylor'' | ||

| + | :“3. A [[jet]]; a spouting of water; an artificial spring. ''Bacon''. | ||

| + | :“4. The head or source of a river. ''Dryden''. | ||

| + | :“5. Original; first principle or cause; the source of any thing.” | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | *Anonymous, April 1, 1837, “Landscape Gardening” (''Horticultural Register'' 3: 129)<ref>Anonymous, “Landscape Gardening,” ''Horticultural Register, and Gardener’s Magazine'' 3 (April 1, 1837): 121–31, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/TBFISAR7 view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“'''Fountains''' are going out of use, though we think without sufficient reason. In more frequented grounds, such as public [[square]]s in towns, we think them particularly appropriate. We would not, however, propose even for these, such expensive '''fountains''' as are frequently seen in Europe, where water is poured forth in immense volumes in marble [[basin]]s, amid tritons and sea horses, and cars. A single streak of water would be a more pleasing object.” | ||

| − | |||

| − | : | + | *Adams, Nehemiah, 1838, ''The Boston Common'' (1838: 21–22, 25–26)<ref>Nehemiah Adams, ''The Boston Common, or Rural Walks in Cities'' (Boston: George W. Light, 1838), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/E29QRTC3 view on Zotero].</ref> |

| − | : | + | :“Much as public [[square]]s, and [[park]]s, and [[avenue]]s, and '''fountains''' contribute to the beauty of a city, they are no less necessary to its salubrity. It was not intended by the Creator that the habitations of men should be piled upon each other, as they are in some cities, almost like boxes of merchandize in a warehouse; and he has made no provision for the security of life and health, under the circumstances which preclude the supply of an abundance of fresh and pure air. |

| − | + | :“But '''fountains''', in these and similar places [such as [[Boston Common]] and other sites nearby], seem still more important. . . Pure water is no less indispensible to the health of a city than pure air. And in this case, as probably in every other, beauty and usefulness go hand in hand. Abundant supplies of pure, fresh water ought to be within the reach of every inhabitant, while the public places should be adorned with '''fountains''' affording water for every public use.” | |

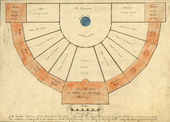

| − | * | + | *Anonymous, July 28, 1842, “Words of a Solomon and Sacred Roll. . .” (Western Reserve Historical Society Library, Shaker Manuscript Collection, reel 67VIIA43) |

| + | :“And thus follows my Law, concerning the Holy '''Fountain''', and the meeting ground, that is attached thereto, with the high way leading to the same. | ||

| + | :“Around the '''Fountain''', upon this my holy Mountain, have I caused five posts of red cedar to be placed, standing thus two upon the east side, two upon the west side, & one at the South end; and at the north end I have caused a white marble stone to be created, whereon my word is written for the nations of the earth to behold, & at each edge of this stone is placed two smaller cedar posts, to which the ends of the guard boards are attached, which encompass the '''fountain'''. | ||

| + | :“These five posts should be about 5 inches square at the base, or lower end, & about 3 at the top with the ends rounded over from each side: standing above the surface of the ground about two feet. | ||

| + | :“Ye shall make the face of the '''fountain''' smooth & even, & when once prepared, step not upon it, or suffer the feet of beasts to tread thereon, for it is holy unto me, saith the Lord. | ||

| + | :“And it is my will that all such as have not yet received their '''fountain''', & set their posts around the same should aim to make them uniform, so far as is practicable, with that established on the Holy mount. . . | ||

| + | :“Place also a guard board around the '''fountain''', one foot from the surface of the ground. If the '''fountain''' be located upon a level surface, or thereabouts; paint this and the posts also white.” | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | *[[Jane Loudon|Loudon, Jane]], 1845, ''Gardening for Ladies'' (1845: 213–14)<ref>Jane Loudon, ''Gardening for Ladies; and Companion to the Flower-Garden'', ed. A. J. Downing (New York: Wiley & Putnam, 1845), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/3Q5GCH4I view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“'''FOUNTAINS''' are of two kinds; [[jet]]s, which rise up in a single tube of water to a great height, and then fall in mist or vapour; and drooping '''fountains''', which are forced up through a pipe, terminated by a kind of rose pierced with holes, called an adjutage, which makes the water assume some particular shape in descending. The principle on which '''fountains''' are constructed is, that if a large quantity of water be contained in a cistern, or other reservoir, in any elevated situation, and pipes be contrived from it to carry the water down to the ground, and along its surface, that the water will always attempt to rise to its own level the moment it can find a vent. . . . The height to which a [[jet]] of water will ascend, therefore, depends on the height which the cistern that is to supply it is above the ground from which it is to ascend; and on the size of the orifice through which it is to issue. . . | ||

| + | :“Drooping '''fountains''' do not require the water to rise so high for them as for [[jet]]s; and consequently the cistern need not be so much elevated. The beauty of '''fountains''' of this kind depends on the adjutages, which are so contrived as to throw the water in many different forms. For example, some are intended to represent a dome, and others a convolvulus, a basket, a wheatsheaf, and a variety of other devices. The water from these '''fountains''' is generally received into a shell, whence it forms a sort of miniature [[cascade]] to the [[basin]] below.” | ||

| − | |||

| − | : | + | [[File:0401.jpg|thumb|Fig. 18, Anonymous, “Design for a Fountain,” in [[A. J. Downing]], ''A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening'' (1849), 466, fig. 91.]] |

| − | + | *<div id="Johnson"></div>Johnson, George William, 1847, ''A Dictionary of Modern Gardening'' (1847: 233–34)<ref>George William Johnson, ''A Dictionary of Modern Gardening'', ed. David Landreth (Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1847), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/D6PQSNAN view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“'''FOUNTAINS''' surprise by their novelty, and the surprise is proportioned to the height to which they throw the water; but these perpendicular [[column]]s of water have no pretence to beauty. The Emperor '''fountain''' at Chatsworth is the most surprising in the world, for it tosses its waters to a height of two hundred and sixty-seven feet, impelled by a [[Fall/Falling garden|fall]] from a reservoir three hundred and eight-one feet above the ajutage, or mouth of the pipe from which it rushes into the air. | |

| − | + | :“For an interesting description of this '''fountain''' and the grounds at Chatsworth, the [[seat]] of the Duke of Devonshire, see [[A. J. Downing|Downing’s]] ‘Horticulturist.’. . | |

| − | : | + | :“''Ajutages''—‘Some are contrived so as to throw up the water in the form of sheaves, fans, showers, to support balls, &c. Others to throw it out horizontally, or in curved lines, according to the taste of the designer; but the most usual form is a simple opening to throw the spout or [[jet]] upright. The grandest [[jet]] of any is a perpendicular [[column]] issuing from a rocky base, on which the water falling produces a double effect both of sound and visual display. A [[jet]] rising from a naked tube in the middle of a [[basin]] or [[canal]], and the waters falling on its smooth surface, is unnatural without being artificially grand.’—''Gard. Enc''. |

| − | + | :“Drooping '''fountains''', or such as bubbling from their source trickle over the edge of rocks, shells, or [[vase]]s, combining the [[cascade]] with the '''fountain''', are capable of much greater beauty.” [[#Johnson_cite|back up to History]] | |

| − | * | + | [[File:0402.jpg|thumb|Fig. 19, Anonymous, "A simple jet. . . the simplest and most pleasing of fountains," in [[A. J. Downing]], ''A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening'' (1849), 471, fig. 92.]] |

| + | *[[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing, Andrew Jackson]], 1849, ''A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening'' (1849; repr., 1991: 427, 466, 471–72)<ref>A. J. Downing, ''A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening'', 4th ed. (1849; repr., Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1991), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/K7BRCDC5 view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“The flowers are generally planted in [[bed]]s in the form of circles, octagons, [[square]]s, etc., the centre of the garden being occupied by an elegant [[vase]], a [[sundial]], or that still finer ornament, a '''fountain''', or ''[[jet|jet d’eau]]''. . . | ||

| + | :“'''''Fountains''''' are highly elegant garden decorations, rarely seen in this country; which is owing, not so much, we apprehend, to any great cost incurred in putting them up, or any want of appreciation of their sparkling and enlivening effect in garden scenery, as to the fact that there are few artisans here, as abroad, whose business it is to construct and fit up architectural, and other ''[[jet|jets d’eau]]''. . . [Fig. 18] | ||

| − | : | + | [[File:0403.jpg|thumb|252px|Fig. 20, Anonymous, “Tazza Fountain,” in [[A. J. Downing]], ''A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening'' (1849), 471, fig. 93.]] |

| + | :“A simple [[jet]] (Fig. 92) issuing from a circular [[basin]] of water, or a cluster of perpendicular [[jet]]s (candelabra [[jet]]s), is at once the simplest and most pleasing of '''fountains'''. Such are almost the only kinds of '''fountains''' which can be introduced with propriety in simple scenes where the predominant objects are sylvan, not architectural. [Fig. 19] | ||

| + | :“Weeping, or ''Tazza '''Fountains''''', as they are called, are simple and highly pleasing objects, which require only a very moderate supply of water compared with that demanded by a constant and powerful [[jet]]. The conduit pipe rises through and fills the [[vase]], which is so formed as to overflow round its entire margin. . . [Fig. 20] | ||

| + | :“'''Fountains''' of a highly artificial character are happily situated only when they are placed in the neighborhood of buildings and architectural forms. When only a single '''fountain''' can be maintained in a residence, the centre of the flower-garden, or the neighborhood of the [[piazza]] or [[terrace]]-[[walk]], is, we think, much the most appropriate situation for it. There the liquid element, dancing and sparkling in the sunshine, is an agreeable feature in the scene, as viewed from the windows of the rooms; and the falling watery spray diffusing coolness around is no less delightful in the surrounding stillness of a summer evening.” | ||

| − | + | [[File:1598.jpg|thumb|Fig. 21, Anonymous, “The Fountain of St. Peter’s,” in [[A. J. Downing]], ed., ''Horticulturist'' 5, no. 5 (November 1850): 209, fig. 56.]] | |

| + | *Humphreys, Henry Noel, November 1850, “Notes on Decorative Gardening—Fountains” (''Horticulturist'' 5: 208–9)<ref>Henry Noel Humphreys, “Notes on Decorative Gardening-Fountains,” ''Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste'' 5, no. 5 (November 1850)" 208–11, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/RF8S8ZNF view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“The most highly wrought effects produced in garden architecture have been those effected by means of '''fountains'''; of this, the well-known [[gardenesque]] water-works of Versailles and St. Cloud are sufficient evidence. . . | ||

| + | :“as '''fountains''' produce the best effect near buildings, and in combination with [[statue|statuary]], architects and sculptors, like Bernini, says Sir U. Price, would not think of inquiring what were the precise forms of natural water-spouts; but knowing that water forced into the air must necessarily assume a great variety of beautiful effects, which, added to its native clearness and brilliancy, would admirably accord with the forms and colours of [[statue]]s and architecture, would use it accordingly. . . . | ||

| + | :“Therefore, while still water finds its more appropriate locality in the lower portion of the grounds, '''fountains''' may be more properly placed in the higher levels of a garden, as their evidently artificial character seems to find its appropriate situation in a position where water would be highly desirable and ornamental, but where it could only be brought by scientific and artistic means. Here, then, the display of art, even to a degree of ostentation, becomes legitimate; and '''fountains''', of elaborate character and complicated architectural design, find their most imposing station at the extremities, or centres, of elevated [[terrace]]s, and places of similar character, where the [[gardenesque]], and semi-architectural character of the surrounding scene, is all in artistic harmony with them.” [Fig. 21] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | *New York State Lunatic Asylum Trustees, 1851, in the annual report, describing the ideal grounds for a lunatic asylum (quoted in Hawkins 1991: 53)<ref>Kenneth Hawkins, “The Therapeutic Landscape: Nature, Architecture, and Mind in Nineteenth-Century America” (PhD diss., University of Rochester, 1991), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/UVDGPDHG view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“The salutary influence on the insane mind of highly cultivated [[lawn]]s—pleasant [[walk]]s amid shade trees, [[shrubbery]], and '''fountains''', beguiling the long hours of their [''sic''] tedious confinement—giving pleasure, content, and health, by their beauty and variety, are fully appreciated by us.” | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | <hr> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Images== | ==Images== | ||

| Line 319: | Line 283: | ||

<gallery widths="170px" heights="170px" perrow="7"> | <gallery widths="170px" heights="170px" perrow="7"> | ||

| − | Image: | + | Image:1412.jpg|Stephen Switzer, “Designs for [[Parterre]] [[Quarter]]s,” in ''Ichnographia Rustica'', 2 vols. (1718), vol. 2, pl. 29. “A large [[Parterre]] [[Quarter]] with a '''Fountain''' in the middle.” |

| − | Image: | + | Image:1390.jpg|Batty Langley, “The Design of a '''Fountain''' & [[Cascade]] after the grand Manner at Versailes,” in ''New Principles of Gardening'' (1728), pl. XVII. |

| − | Image: | + | Image:0461.jpg|[[Samuel Vaughan]], Plan of [[Bath/Bathhouse|Bath]] [[Berkeley Springs|[Berkeley Springs]]], VA [detail], 1787, from the diary of Samuel Vaughan, June–September 1787. “d. the drinking spring or '''Fountain'''.” |

| − | Image: | + | Image:0474.jpg|Peter Maverick, Trade card depicting Joseph de Lacroix’s [[Ice House]], c. 1796. |

| − | Image: | + | Image:0460.jpg|Charles Varlé, ''Project for the Improvement of the [[Square]] and the Town of Bath'', 1809. “E. Reservoir or fountain. . .” |

| − | Image: | + | Image:1221.jpg|[[Robert Mills]], Plan of wings and courtyards, South Carolina Insane Asylum, 1821. “Fountain [[basin]].” |

| − | Image:1336.jpg|[[J. C. Loudon]], | + | Image:1336.jpg|[[J. C. Loudon]], “Drooping '''fountains''',” in ''An Encyclopædia of Gardening'' (1826), 359, figs. 341–43. |

| − | Image:1826.jpg|[[J. C. Loudon]], Fountain supplied from a cistern, in ''The Suburban Gardener'' (1838), | + | Image:1826.jpg|[[J. C. Loudon]], '''Fountain''' supplied from a cistern, in ''The Suburban Gardener'' (1838), 582, fig. 233. |

| − | Image: | + | Image:0989.jpg|Anonymous, Plan of '''Fountain''' on Holy Mountain, August 1, 1842. |

| − | Image: | + | Image:0996.jpg|Anonymous, “A Small Arabesque [[Flower Garden]],” in [[A. J. Downing]], ed., ''Horticulturist'' 2, no. 11 (May 1848): 504. “The centre of this garden, ''i'', is supposed to be occupied by. . . a '''fountain'''.” |

| − | Image: | + | Image:0575.jpg|Lewis Miller, “Sweet Music, like the '''Fountain''' Springs,” in ''Orbis Pictus'' (c. 1849), 44. |

| − | Image: | + | Image:0577.jpg|Lewis Miller, “Die Lebens Quelle,” in ''Orbis Pictus'' (c. 1849), 51. |

| − | Image: | + | Image:0401.jpg|Anonymous, “Design for a '''Fountain''',” in [[A. J. Downing]], ''A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening'' (1849), 466, fig. 91. |

| − | Image: | + | Image:0402.jpg|Anonymous, "A simple [[jet]]. . . the simplest and most pleasing of '''fountains'''," in [[A. J. Downing]], ''A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening'' (1849), 471, fig. 92. |

| − | Image: | + | Image:0403.jpg|Anonymous, “Tazza '''Fountain''',” in [[A. J. Downing]], ''A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening'' (1849), 471, fig. 93. |

| − | Image: | + | Image:0497.jpg|Anonymous, “[[Bowling Green]] '''Fountain''',” in E. Porter Belden, ''New-York: Past, Present, and Future'' (1850), opp. 30. |

| − | Image:1598.jpg|Anonymous, | + | Image:1598.jpg|Anonymous, “The '''Fountain''' of St. Peter’s,” in [[A. J. Downing]], ed., ''Horticulturist'' 5, no. 5 (November 1850): 209, fig. 56. |

| − | Image:1967.jpg|[[A. J. Downing]], | + | Image:1967.jpg|[[A. J. Downing]], ''Plan Showing Proposed Method of Laying Out the [[Public_garden/Public_ground|Public Grounds]] at Washington'', 1851. |

| − | Image:0023.jpg|[[A. J. Downing]], | + | Image:0023.jpg|[[A. J. Downing]], ''Plan Showing Proposed Method of Laying Out the [[Public_garden/Public_ground|Public Grounds]] at Washington'', 1851. Manuscript copy by Nathaniel Michler, 1867. |

| + | Image:0023_detail3.jpg| [[A. J. Downing]], ''Plan Showing Proposed Method of Laying Out the [[Public_garden/Public_ground|Public Grounds]] at Washington'', 1851 [detail]. Manuscript copy by Nathaniel Michler, 1867. | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

| Line 362: | Line 327: | ||

<gallery widths="170px" heights="170px" perrow="7"> | <gallery widths="170px" heights="170px" perrow="7"> | ||

| − | Image: | + | Image:1055.jpg|Michael van der Gucht, “Four Designs for Cloisters,” in A.-J. Dézallier d’Argenville, ''The Theory and Practice of Gardening'' (1712), pl. 9. |

| − | Image: | + | Image:0669.jpg|Cornelius Tiebout, after John James Barralet, ''[[View]] of the Water Works at Centre Square Philadelphia'', c. 1812. |

| − | Image: | + | Image:0551.jpg|John Lewis Krimmel, ''Fourth of July in Centre [[Square]]'', 1812. |

| − | Image: | + | Image:0044.jpg|[[Charles Willson Peale]], ''[[View]] of the garden at [[Belfield]]'', 1816. |

| − | Image: | + | Image:0044_detail3.jpg|[[Charles Willson Peale]], ''[[View]] of the garden at [[Belfield]]'', [detail] 1816. |

| − | Image: | + | Image:0063.jpg|[[Benjamin Henry Latrobe]], “Plan of the public [[Square]] in the city of New Orleans, as proposed to be improved. . .” [detail], March 20, 1819. |

| − | Image: | + | Image:1202.jpg|Frederick Graff, Design for the ''Boy and Dolphin'' '''Fountain''', Fairmount Waterworks, 1829. |

| − | Image: | + | Image:0537.jpg|Tucker Factory, Pair of vases with [[view]]s of the Fairmount Waterworks, c. 1830. |

| − | Image: | + | Image:0536.jpg|George Lehman, ''Fairmount Waterworks. From the Forebay'', 1833. Fountain visible on the left in front of the stairways. |

| − | Image: | + | Image:1298.jpg|Nicolino Calyo, ''[[View]] of the Waterworks at Fairmount'', 1835—36. |

| − | Image: | + | Image:1239.jpg|George Washington Sully, ''[[View]] of the New Orleans River Front from Canal Street to the Place d’Armes'', 1836. The fountain is in the center of the image. [<span id="Fig_13_cite"></span>[[#Fig_13|See Fig. 13]]] |

| − | Image: | + | Image:2256.jpg|John Henry Bufford. ''Fairmount from the first Landing'', cover illustration for sheet music for ''The Fairmount Quadrilles'', 1836, lithographs. Courtesy of the Free Library of Philadelphia, Print and Picture Department. |

| − | Image:1120.jpg|W. H. Bartlett, | + | Image:1120.jpg|W. H. Bartlett, “Fairmount Gardens, with the Schuylkill Bridge. (Philadelphia),” in Nathaniel Parker Willis, ''American Scenery'', 2 vols. (1840), vol. 2, pl. 24. |

| − | Image:0032.jpg|[[Robert Mills]], | + | Image:0032.jpg|[[Robert Mills]], ''[[Picturesque]] [[View]] of the Building, and Grounds in front'', 1841. |

Image:0034.jpg|[[Robert Mills]], Alternative plan for the grounds of the National Institution, 1841. | Image:0034.jpg|[[Robert Mills]], Alternative plan for the grounds of the National Institution, 1841. | ||

| − | Image:0483.jpg|Anonymous, | + | Image:0483.jpg|Anonymous, ''Croton Water Celebration 1842'', 1842. |

| − | Image: | + | Image:2283.jpg|Anonymous (artist), Nathaniel Currier (lithographer), ''[[View]] of the Great Conflagration at New York July 19th 1845'', 1845. |

| − | Image: | + | Image:0941.jpg|Anonymous, “A pair of ''tozza'' [''sic''] [[vase]]s, for a '''fountain''',” in [[A. J. Downing]], ed., ''Horticulturist'' 3, no. 1 (July 1848): 42, fig. 13. |

| − | Image: | + | Image:0576.jpg|Lewis Miller, “In beauteous Order Terminate the Scene. . . ,” in ''Orbis Pictus'' (c. 1849), 46. |

| − | Image: | + | Image:0484.jpg|John Bachmann, ''New York City Hall, [[Park]] and Environs'', c. 1849. |

| − | Image: | + | Image:0478.jpg|Benjamin Franklin Smith, Jr., ''[[View]] of the Water Celebration, on [[Boston Common]] October 25<sup>th</sup> 1848'', 1849. |

| − | Image: | + | Image:0612.jpg|John Bachmann, ''Bird’s Eye [[View]] of Boston'', c. 1850. |

| + | </gallery> | ||

| − | + | ===Attributed=== | |

| + | <gallery widths="170px" heights="170px" perrow="7"> | ||

| − | Image: | + | Image:0255.jpg|John Singleton Copley, ''Rebecca Boylston'', 1767. |

| − | + | Image:2274.jpg|[[Pierre Pharoux]], Plan of Courthouse [[Square]] in Esperanza, Architectural drawings and maps of Pierre Pharoux, 1795, HM 2028. | |

| + | |||

| + | Image:2115.jpg|Pavel Petrovich Svinin, ''Centre [[Square]] and the Marble Works, Philadelphia'', 1811–c. 13. | ||

| − | + | Image:1464.jpg|Joseph Jacques Ramée, Plan of Union College, 1813. | |

| − | |||

| − | Image: | + | Image:0902.jpg|George Bridport, Design for Washington Monument, [[Washington Square (Philadelphia)|Washington Square]], Philadelphia, 1816. |

| − | Image: | + | Image:0006.jpg|Harriet De (?), ''The Duck [[Pond]]'', c. 1820. |

| − | Image: | + | Image:0521.jpg|William Rush, ''North East or Franklin Public [[Square]], Philadelphia'', 1824. |

| − | Image: | + | Image:1173.jpg|Anonymous, The Diploma for the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, c. 1836, in ''Yearbook of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society'' (1956), frontispiece. |

| − | Image: | + | Image:0622.jpg|John Warner Barber (artist), S. E. Brown (engraver), “Court [[Square]] in Springfield, Mass.,” in John Warner Barber, ''Historical Collections'' (1844), pl. opp. 290. |

| − | Image: | + | Image:0523.jpg|[[Frances Palmer]] (artist), Nathaniel Currier (lithographer), ''Union Place Hotel, Union [[Square]] New-York'', c. 1845. |

| − | Image: | + | Image:1508.jpg|Anonymous, "English Rural Cottage," ''Horticulturist,'' Vol. 2, No. 2 (August 1847), pl. opp. 57 |

| − | Image: | + | Image:0476.jpg|James Smillie (artist), Sarony & Major (printers), ''[[View]] of Union [[Park]], New York, from the Head of Broadway'', 1849. |

| − | Image: | + | Image:2116.jpg|Edwin Whitefield, '''''Fountain''' [[Park]] near Philadelphia. Residence of A. McMakin Esq.'', c. 1850. |

Image:1993.jpg|John O'Brien Inman, Inman Homestead, c. 1850. | Image:1993.jpg|John O'Brien Inman, Inman Homestead, c. 1850. | ||

| − | Image:0438.jpg|Anonymous, ''Leaving the Manor House'', c. | + | Image:0438.jpg|Anonymous, ''Leaving the Manor House'', c. 1850–55. |

| − | Image: | + | Image:2261.jpg|Benjamin Franklin Smith Jr. (artist), William Wellstood (engraver), ''New York 1855. From the Latting Observatory'', 1855. The '''fountain''' can be seen to the middle-left of the reservoir. |

| + | |||

| + | Image:2261_detail1.jpg|Benjamin Franklin Smith Jr. (artist), William Wellstood (engraver), ''New York 1855. From the Latting Observatory'' [detail], 1855. | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <hr> | ||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| Line 447: | Line 419: | ||

[[Category: Keywords]] | [[Category: Keywords]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Water Features]] | ||

Latest revision as of 16:06, April 1, 2021

History

Numerous European treatises stressed the fountain as a principal ornament of the garden. Its popularity was attested to by its frequent use in both European and American gardens.[1] Hydraulics (the branch of engineering concerned with moving water), however, did not play a major role in American garden design until the late 18th century, despite the frequent mention of still-water features such as canals, ponds, and pools in garden descriptions. In spite of the rarity of early examples that were executed, the term “fountain” was utilized and was understood to describe a variety of devices that issued water under pressure. This pressure was generated by gravity from an elevated water source—by a pump, or, later, by municipal pressurized water systems. Water, conveyed in pipes, was forced through an aperture that determined the trajectory of the spray. As George William Johnson (1847) and Jane Loudon (1845) described the process, different orifices could project water horizontally, vertically, or in an arc, enabling the designer to create effects simulating the form of a sheaf, fan, dome, or basket. A fountain with a single spout of water was sometimes called by its French synonym, jet d’eau, but larger waterworks, such as those in public squares and parks, were generally referred to as fountains (see Jet).