Difference between revisions of "Canal"

C-tompkins (talk | contribs) (→Images) |

V-Federici (talk | contribs) m (→Inscribed) |

||

| (239 intermediate revisions by 10 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | See also: [[Basin]] | |

==History== | ==History== | ||

| − | + | [[File:0594.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 1, [[Benjamin Henry Latrobe]], ''Section of the northern course of the canal from the tide in the Elk River at Frenchtown to the forked [oak] in Mr. Rudulph’s swamp'', 1803.]] | |

| − | + | The canal was an artificial waterway built for navigation, irrigation, and ornamentation. In general, it was a channel, usually set into the ground, with parallel [[wall]]s made of earth, stone, or brick. Canals varied widely in size: from broad navigable examples, such as the Erie and the Chesapeake & Ohio, to smaller garden ones such as that depicted in a sketch of the [[seat]] of Edmund Quincy [<span id="Fig_8_cite"></span>[[#Fig_8|See Fig. 8]]] in Massachusetts. Within the garden, canals could be straight, an idea promoted by treatise author Humphry Repton (1803), or they could meander, as at the Vale, in Waltham, Massachusetts [<span id="Fig_11_cite"></span>[[#Fig_11|See Fig. 11]]]. In addition to the main channel, garden canals sometimes widened to form a fishpond emptied into a nearby river or pond, or filled a [[basin]] as in [[Benjamin Henry Latrobe|Benjamin Henry Latrobe's]] plan of an aqueduct [Fig. 1] (see [[Basin]]). | |

| − | + | [[File:0881.jpg|thumb|right|Fig. 2, Anonymous, ''Plan de la ville et environs de Williamsburg en Virginie, America'', 1782.]] | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Canals were an element of American landscape design as early as the beginning of the 18th century, <span id="Jones_cite"></span>as attested to by Hugh Jones's 1722 description of the Governor’s Palace in Williamsburg, Virginia ([[#Jones|view text]]) [Fig. 2]. The chronology of American garden canal construction, at least as recorded in garden descriptions, suggests that the popularity of building canals in residential gardens dwindled in the 19th century. They continued to be utilized in public landscape designs, however, as at the [[Columbian Institute]] in Washington, DC Although images of navigable canals, such as the Erie Canal, were popular symbols during this time of America’s burgeoning prosperity and technological achievement [Fig. 3], [[view]]s of private garden canals were rare. | |

| + | [[File:0289.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 3, John William Hill, ''[[View]] on the Erie Canal'', 1829.]] | ||

| − | + | In gardens, canals were less common than still-water features (such as fishponds and pools), most likely because canals required both a continuous water source and a relatively large amount of space. The feasibility of such a canal was obviously dependent upon the availability of water, and, not unexpectedly, garden canals were more common in coastal or riverine areas such as Charleston; Williamsburg; Washington, DC; and Philadelphia. | |

| − | + | [[File:0042.jpg|thumb|Fig. 4, Benjamin Franklin Smith Jr., ''Washington, DC with projected improvements'', c. 1852.]] | |

| − | the | ||

| − | |||

| − | Urban canals, indicated on city plans, were built as commercial transportation | + | Like other water features, canals provided a source of fresh food. The canal of Edmund Quincy supplied eel, Alexander Gordon's canal was stocked with fish, and the canal of Thomas Brattle was noted for its waterfowl. Canals also provided irrigation, ice, and, if large enough, offered opportunities for boating [Fig. 4]. In low-lying areas and in examples such as Garden’s waterway (which was fed by fresh springs), the canal also offered drainage for excess water. Like other water features, they provided a garden with the animation of moving or rippling water, the cooling effect of evaporation, the visual interest of reflective surfaces, and habitats for swans and other ornamental birds. The slow flow and placid surface of a canal might stand in contrast to the burbling course of a stream or the dynamic rush of a [[cascade]]. With a border of flowers, a canal might, <span id="Repton_cite"></span>as Repton (1803) suggested, lend “to the whole an air of neatness and careful attention” ([[#Repton|view text]]). |

| − | routes, but these canals were also embraced in efforts to create healthful, recreational areas for city dwellers. Banks along some navigable canals were ornamented with [[walk]]s, benches, and [[fence]]s. In other cases, canals constructed for commercial or navigational purposes were incorporated in public landscape design schemes, as at Fairmount Park in Philadelphia [Fig. | + | [[File:1994.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 5, Thomas Doughty, ''[[View]] of the Fairmount Waterworks, Philadelphia, from the Opposite Side of the [[Schuylkill River]]'', c. 1824—26.]] |

| + | [[File:0033.jpg|thumb|Fig. 6, [[Robert Mills]], ''Plan of the [[Mall]]'', Washington, DC, 1841.]] | ||

| + | Urban canals, indicated on city plans, were built as commercial transportation routes, but these canals were also embraced in efforts to create healthful, recreational areas for city dwellers. Banks along some navigable canals were ornamented with [[walk]]s, benches, and [[fence]]s. In other cases, canals constructed for commercial or navigational purposes were incorporated in public landscape design schemes, as at Fairmount Park in Philadelphia [Fig. 5] and the [[national Mall]] in Washington, DC [Fig. 6]. At Fairmount Park, which is depicted on a painted [[vase]] [Fig. 7], the canal for the pumping station became a popular [[promenade]]. In Washington, designers such as [[Pierre-Charles L'Enfant]], [[Benjamin Henry Latrobe]], Charles Bulfinch, and [[Robert Mills]] used the canal as an integral element of their plans for the [[national Mall]], routing it to accentuate the [[view]] of the capitol and ornamenting it with [[bridge]]s and [[walk]]s. Latrobe’s Plan of the Capitol (1815) incorporated a waterway he referred to as a Canal [<span id="Fig_10_cite"></span>[[#Fig_10|See Fig. 10]]]. L'Enfant even proposed an ambitious scheme to have water run under the U.S. Capitol and then [[cascade]] into the canal below, at the level of the [[national Mall|Mall]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:0537.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 7, Tucker Factory, Pair of [[vase]]s with [[view]]s of the Fairmount Waterworks, c. 1830.]] | ||

| + | <span id="Johnson_cite"></span>Samuel Johnson's 1755 definition of a canal as a “course of water made by art” ([[#Johnson|view text]]), and <span id="Sheridan_cite"></span>Thomas Sheridan's 1789 definition ([[#Sheridan|view text]]) are particularly telling for the canal’s significance in a landscape-design context. The use of art and water points to the canal’s combination of the artificial and the natural, a juxtaposition that is at the essence of any garden. A canal, in particular, resonates with the theme; it carries water, a basic element in the garden, yet the hand of its human creator is obvious in the contrived regularity of its construction. <span id="Garden_cite"></span>[[Alexander Garden|Dr. Alexander Garden]] (1754), in reference to [[Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery|Bartram’s Garden]], noted that the botanist’s enthusiastic attempt to put the stamp of art on every natural feature, culminated in a design in which “[e]very run of water, [was] a Canal” ([[#Garden|view text]]). | ||

| − | + | —''Elizabeth Kryder-Reid'' | |

| − | + | <hr> | |

==Texts== | ==Texts== | ||

| − | |||

===Usage=== | ===Usage=== | ||

| + | *<div id="Jones"></div>Jones, Hugh, 1722, describing the Governor’s Palace, Williamsburg, VA (1956: 70)<ref>Hugh Jones, ''The Present State of Virginia, From Whence Is Inferred a Short View of Maryland and North Carolina'', ed. Richard L. Morton (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1956), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/KE293JVS view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| − | + | :“. . . the Palace or Governor’s House, a magnificent structure, built at the publick expence, finished and beautified with [[gate]]s, fine gardens, offices, [[walk]]s, a fine '''canal''', [[orchard]]s, etc. with a great number of the best arms nicely posited, by the ingenious contrivance of the most accomplished Colonel Spotswood.” [[#Jones_cite|back up to History]] | |

| − | |||

| − | + | *Hamilton, Alexander, July 17, 1744, describing Malbone Hall, country seat of Godfrey Malbone, Newport, RI (1948: 103)<ref>Alexander Hamilton, ''Gentleman’s Progress: The Itinerarium of Dr. Alexander Hamilton, 1744'', ed. Carl Bridenbaugh (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1948), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/EWWJNEUN view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | * Hamilton, Alexander, 17 | ||

:“This house makes a grand show att a distance but is not extraordinary for the architecture, being a clumsy Dutch modell. Round it are pritty gardens and terrasses with '''canals''' and basons for water.” | :“This house makes a grand show att a distance but is not extraordinary for the architecture, being a clumsy Dutch modell. Round it are pritty gardens and terrasses with '''canals''' and basons for water.” | ||

| − | * Anonymous, 22 | + | *Anonymous, May 22, 1749, describing the kitchen garden of [[Alexander Garden]], Charleston, SC (''South Carolina Gazette'') |

| − | : | + | :“. . . at the end of which is a '''canal''' supplied with fresh springs of water, about 300 feet long, with fish.” |

| − | * Goelet, Capt. Francis, c. 1750, describing the residence and garden of Edmund Quincy, Boston, | + | <div id="Fig_8"></div>[[File:1176.jpg|thumb|Fig. 8, Eliza Susan Quincy, “[[View]] of the [[seat]] of Edmund Quincy Esqr.,” 1822. [[#Fig_8_cite|Back up to history.]]]] |

| + | *Goelet, Capt. Francis, c. 1750, describing the residence and garden of Edmund Quincy, Boston, MA (quoted in Pearson 1980: 6)<ref>Danella Pearson, “Shirley-Eustis House Landscape History,” ''Old-Time New England'' 70 (1980): 1–16, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/E2F8TJTH view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| − | : | + | :“. . . about Ten Yards from the House is a Beautiful '''Cannal''', which is Supplyd by a Brook which is well Stockt with Fine Silver Eels, we Cought a fine Parcell and carried them Home and had them drest for Supper, the House has a Beautifull [[Pleasure ground|Pleasure Garden]] Adjoyning it, and on the Back Part the Building is a Beautiful [[Orchard]] with fine fruit trees, etc.” [Fig. 8] |

| − | * Garden, Dr. Alexander, 1754, in a letter to Cadwallader Colden, describing Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery, vicinity of Philadelphia, | + | [[File:0056.jpg|thumb|Fig. 9, [[John Bartram|John]] or [[William Bartram]], "A Draught of [[Bartram_Botanic_Garden_and_Nursery|John Bartram’s House and Garden]] as it appears from the River", 1758.]] |

| + | *<div id="Garden"></div>[[Alexander Garden|Garden, Dr. Alexander]], 1754, in a letter to [[Cadwallader Colden]], describing [[Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery]], vicinity of Philadelphia, PA (Colden 1920: 4: 472)<ref>Cadwaller Colden, ''The Letters and Papers of Cadwallader Colden'', 9 vols. (New York: New-York Historical Society, 1918–37), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/UT8C2FTZ view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| − | : | + | :“. . . he disdains to have a garden less than Pensylvania & Every den is an Arbour, Every run of water, a '''Canal''', & every small level Spot a [[Parterre]].” [Fig. 9] [[#Garden_cite|back up to History]] |

| − | *Shippen, Thomas Lee, 31 | + | *Shippen, Thomas Lee, December 31, 1783, describing Westover, seat of William Byrd III, on the James River, VA (1952: n.p.)<ref>Thomas Lee Shippen, Westover ''Described in 1783: A Letter and Drawing Sent by Thomas Lee Shippen, Student of Law in Williamsburg, to His Parents in Philadelphia'' (Richmond, VA: William Byrd Press, 1952), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/3IWWPMJ5 view on Zotero.]</ref> |

| − | :“These [[meadow]]s well watered with '''canals''', which communicate with each other across the road give occasion every 50 yards for a [[bridge]]; and between every two [[bridge]]s are two [[gate]]s one on each side the road.” | + | :“These [[meadow]]s well watered with '''canals''', which communicate with each other across the road give occasion every 50 yards for a [[bridge]]; and between every two [[bridge]]s are two [[gate]]s one on each side the road.” |

| − | * L’Enfant, Pierre-Charles, 22 | + | <div id="Fig_10"></div>[[File:0035.jpg|thumb|Fig. 10, [[Benjamin Henry Latrobe]], Plan of the Capitol grounds, 1815. [[#Fig_10_cite|Back up to history.]]]] |

| + | *[[Pierre-Charles L’Enfant|L'Enfant, Pierre-Charles]], June 22, 1791, describing his plans for Washington, DC (quoted in Caemmerer 1950: 152–53)<ref>H. Paul Caemmerer, ''The Life of Pierre-Charles L’Enfant, Planner of the City Beautiful, The City of Washington'' (Washington, DC: National Republic Publishing Company, 1950), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/PHWTAERT view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| − | :“a '''canal''' being easy to open from the eastern branch and to be lead across the first settlement and carried toward the mouth of the [T]iber where it will again give an issue into the Potowmack and at a distance not to far off for to admit the boats from the grand navigation '''canal''' from getting in, will undoubtedly facilitate a conveyance most advantageous to trading Interest. . . | + | :“a '''canal''' being easy to open from the eastern branch and to be lead across the first settlement and carried toward the mouth of the [T]iber where it will again give an issue into the Potowmack and at a distance not to far off for to admit the boats from the grand navigation '''canal''' from getting in, will undoubtedly facilitate a conveyance most advantageous to trading Interest. . . |

| − | + | :“I propose in this map, of leting the [T]iber return in its proper channel by a [[Fall/Falling garden|fall]] which issuing from under the base of the Congress building may there form a [[cascade]] of forty feet heigh [''sic''] or more than one hundred waide [''sic''] which would produce the most happy effect in rolling down to fill up the '''canall''' [''sic''] and discharge itself in the Potowmack of which it would then appear as the main spring when seen through that grand and majestic [[avenue]] intersecting with the [[prospect]] from the palace.” [Fig. 10] | |

| − | :“I propose in this map, of leting the [T]iber return in its proper channel by a [[fall]] which issuing from under the base of the Congress building may there form a [[cascade]] of forty feet heigh [''sic''] or more than one hundred waide [''sic''] which would produce the most happy effect in rolling down to fill up the '''canall''' [''sic''] and discharge itself in the Potowmack of which it would then appear as the main spring when seen through that grand and majestic [[avenue]] intersecting with the [[prospect]] from the palace.” [ | ||

| − | * Bentley, William, 4 | + | *Bentley, William, October 4, 1792, describing the residence of Thomas Brattle, Cambridge, MA (1962: 1:398)<ref>William Bentley, ''The Diary of William Bentley, D.D., Pastor of the East Church, Salem, Massachusetts'', 2 vols. (Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1962), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/B63ABACF view on Zotero].</ref> |

| − | :“I visited Mr Brattle’s Gardens, &c. at Cambridge. We first saw the [[fountain]] & '''canal''' opposite to his House, & the [[walk]] on the side of another '''canal''' in the road, flowing under an [[arch]] & in the direction of the outer [[fence]]. There is another '''canal''' which communicates with a beautiful pool in the [[park]] & place for his wild fowl.” | + | :“I visited Mr Brattle’s Gardens, &c. at Cambridge. We first saw the [[fountain]] & '''canal''' opposite to his House, & the [[walk]] on the side of another '''canal''' in the road, flowing under an [[arch]] & in the direction of the outer [[fence]]. There is another '''canal''' which communicates with a beautiful pool in the [[park]] & place for his wild fowl.” |

| − | *La Rochefoucauld Liancourt, | + | *La Rochefoucauld Liancourt, François Alexandre-Frédéric, duc de, 1799, describing Middleton Place, seat of Henry Middleton, near Charleston, SC (1800: 2:438)<ref>François-Alexandre-Frédéric, duc de la Rochefoucauld-Liancourt, ''Travels through the United States of North America, the Country of the Iroquois, and Upper Canada, in the Years 1795, 1796, and 1797'', ed. Brisson Dupont and Charles Ponges, trans. H. Newman, 2nd ed., 4 vols. (London: R. Philips, 1800), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/SRMDWJ2M view on Zotero].</ref> |

| − | :“A peculiar feature of the situation is this, that the river, which flows in a circuitous course, until it reaches this point, forms here a wide, beautiful '''canal''', pointing straight to the house.” | + | :“A peculiar feature of the situation is this, that the river, which flows in a circuitous course, until it reaches this point, forms here a wide, beautiful '''canal''', pointing straight to the house.” |

| − | * Scott, Joseph, 1806, describing Fairmount Waterworks, Philadelphia, | + | *Scott, Joseph, 1806, describing Fairmount Waterworks, Philadelphia, PA (1806: 25–26)<ref>Joseph Scott, ''A Geographical Description of Pennsylvania'' (Philadelphia: Printed by R. Cochran, 1806), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/55XKIWPN view on Zotero].</ref> |

| − | :“The water-works of Philadelphia are the most extensive of their kind of any in America. They consist of a [[basin]], excavated, partly in the [[bed]] of the river Schuylkill, three feet deeper than low-water mark | + | :“The water-works of Philadelphia are the most extensive of their kind of any in America. They consist of a [[basin]], excavated, partly in the [[bed]] of the river Schuylkill, three feet deeper than low-water mark. . . The [[basin]] extends easterly to high-water mark, where it is secured by another [[wall]] and sluice, admitting the water to a '''canal''' 40 feet wide, and 200 feet long. From the east end of the '''canal''', a subteraneous tunnel, conveys the water underneath the edge of the high bank, or plain, upon which the city is built. The '''canal''' and tunnel are hewn out of the solid granite, and their bottoms are three feet below low-water mark. The east end of the tunnel enters a well, sunk from the top of the bank. The well receives the waters of the Schulkill, from the [[basin]], by means of the '''canal'''.” |

| − | * Ripley, Samuel, 1815, describing the Vale, estate of Theodore Lyman, Waltham, | + | <div id="Fig_11"></div>[[File:0716.jpg|thumb|Fig. 11, Alvan Fisher, ''The Vale'', 1820–25. [[#Fig_11_cite|Back up to History.]]]] |

| + | *Ripley, Samuel, 1815, describing the Vale, estate of Theodore Lyman, Waltham, MA (1815: 272)<ref>Samuel Ripley, “A Topographical and Historical Description of Waltham, in the County of Middlesex, Jan. 1, 1815,” ''Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society'' 3 (January 1815): 261–84, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/7INJ3GDV/ view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| − | :“Through the [[lawn]], in front of the mansion house, which is large and handsome, runs Beaver Brook, which it there formed into a serpentine '''canal''', and over which is erected a [[bridge]] of three [[arch]]es, made of the Chelmsford white stone, which is both an ornament to the place, and a specimen of correct taste and workmanship.” | + | :“Through the [[lawn]], in front of the mansion house, which is large and handsome, runs Beaver Brook, which it there formed into a serpentine '''canal''', and over which is erected a [[bridge]] of three [[arch]]es, made of the Chelmsford white stone, which is both an ornament to the place, and a specimen of correct taste and workmanship.” |

| − | * Columbian Institute, 1823, describing the Columbian Institute, Washington, | + | [[File:0034.jpg|thumb|Fig. 12, [[Robert Mills]], Alternative plan for the grounds of the National Institution, 1841.]] |

| + | *[[Columbian Institute]], 1823, describing the Columbian Institute, Washington, DC (quoted in O’Malley 1989: 127)<ref name="O'Malley 1989">Therese O’Malley, “Art and Science in American Landscape Architecture: The National Mall, Washington, DC 1791–1852" (PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1989), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/TQVME883 view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

:“The '''canal''' that surrounds it is 15 feet wide and 2 1/2 feet deep.” | :“The '''canal''' that surrounds it is 15 feet wide and 2 1/2 feet deep.” | ||

| − | *Commissioner of Public Buildings, 9 | + | *Commissioner of Public Buildings, June 9, 1827, describing the [[Columbian Institute]], Washington, DC (quoted in O’Malley 1989: 133)<ref name="O'Malley 1989"></ref> |

| − | :“The new section of the Washington '''Canal''' was laid out along a line drawn through the middle of the Capitol and of the Mall. The pathway, '''canal''' and [[plantation]] in the garden do not coincide with this line, but diverge from it at an acute angle.” | + | :“The new section of the Washington '''Canal''' was laid out along a line drawn through the middle of the Capitol and of the [[national Mall|Mall]]. The pathway, '''canal''' and [[plantation]] in the garden do not coincide with this line, but diverge from it at an acute angle.” [Fig. 12] |

| − | * Downing, | + | *[[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing, Andrew Jackson]], 1851, describing plans for improving the [[public ground]]s in Washington, DC (quoted in Washburn 1967: 55)<ref>Wilcomb E. Washburn, "Vision of Life for the Mall,” ''AIA Journal'' 47 (1967): 52–59, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/TA59MHC7 view on Zotero].</ref> |

:“5th: Fountain Park | :“5th: Fountain Park | ||

| − | :“This Park would be chiefly remarkable for its water features. The [[Fountain]] would be chiefly supplied from a [[basin]] in the Capitol. The [[Pond]] or [[lake]] might either be formed from the overflow of this [[fountain]], or from a filtering drain from the '''canal'''. The earth that would be excavated to form this pond is needed to fill up low places now existing in this portion of the grounds.” | + | :“This Park would be chiefly remarkable for its water features. The [[Fountain]] would be chiefly supplied from a [[basin]] in the Capitol. The [[Pond]] or [[lake]] might either be formed from the overflow of this [[fountain]], or from a filtering drain from the '''canal'''. The earth that would be excavated to form this [[pond]] is needed to fill up low places now existing in this portion of the grounds.” |

| + | |||

===Citations=== | ===Citations=== | ||

| − | * Chambers, Ephraim, 1741–43, '' | + | [[File:1382.jpg|thumb|Fig. 13, Batty Langley, “An Improvement of a beautiful Garden at Twickenham,” in ''New Principles of Gardening'' (1728), pl. IX.]] |

| + | [[File:1383.jpg|thumb|Fig. 14, Batty Langley, One of two “As for Gardens that lye irregularly to the grand House. . . , in ''New Principles of Gardening'' (1728), pl. X.]] | ||

| + | *Langley, Batty, 1728, ''New Principles of Gardening'' (1728; repr., 1982: xii–xiii)<ref>Batty Langley, ''New Principles of Gardening, or The Laying Out and Planting Parterres, Groves, Wildernesses, Labyrinths, Avenues, Parks, &c'' (London: A. Bettesworth and J. Batley, etc., 1728; repr., London: Garland, 1982), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/MRDTAEKC view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | |||

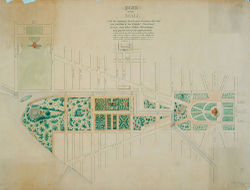

| + | :“Plate IX. is an improvement of a ''beautiful Garden at Twickenham'', situated on the ''River Thames'', which passes by the Line E F, and has a free communication with the '''Canals''' X and Z. . . [Fig. 13] | ||

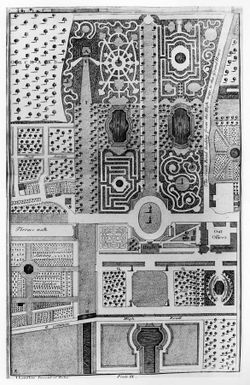

| + | :“Plates X and XI, are Designs for gardens that lye [''sic''] irregularly to the grand House. In Plate X, the House opens to the ''North'' upon the ''[[Park]]'' A, to the ''East'' upon ''Court'' B, to the ''South'' upon the ''[[Parterre]] of Grass and Water'' C; and Lastly to the ''West'' upon the ''circular [[basin|Bason]]'' D, from which leads a ''pleasant [[Avenue]]'' Z X. The ''[[Mount]]'' F, is raised with the Earth that came out of the '''''Canal''''' E E, and its [[Slope]] H is planted with ''[[hedge|Hedges]]'' of ''different Ever-Greens'', that rising behind one another of different Colours have a very good Effect, being view'd form M. I,I are contracts [[Walk]]s leading up to the [[Mount]] . . . [Fig. 14] | ||

| + | :“Plate XII is the Design of a small Garden situated in a ''[[Park]]'', where the House to the ''North'' opens upon ''a noble circular [[Basin]] of Water'' B, in the ''[[Park]]'', and to the ''South'', on a ''grand Parterre of Grass'', from which over the '''''Canal''''' you have a boundless [[View]] into the Country.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | *[[Ephraim Chambers|Chambers, Ephraim]], 1741, ''Cyclopaedia'' (1741: 1:n.p.)<ref>Ephraim Chambers, ''Cyclopaedia, or An Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences . . . '', 5th ed., 2 vols. (London: D. Midwinter et al., 1741–43), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/PTXK378N view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | :“GARDEN. . . | ||

| + | :“The chief furniture of [[pleasure garden]]s are, [[parterre]]s, [[vista]]s, glades, [[grove]]s, compartiments, quincunces, verdant halls, arbour work, mazes, [[labyrinth]]s, [[fountain]]s, cabinets, [[cascade]]s, '''canals''', [[terrace]]s, ''&c''.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | *<div id="Johnson"></div>Johnson, Samuel, 1755, ''A Dictionary of the English Language'' (1755: 1:n.p.),<ref>Samuel Johnson, ''A Dictionary of the English Language: In Which the Words Are Deduced from the Originals and Illustrated in the Different Significations by Examples from the Best Writers'', 2 vols. (London: W. Strahan for J. and P. Knapton, 1755), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/GE2JPJR3/ view on Zotero].</ref> [[#Johnson_cite|back up to History]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | :“'''CANA'L'''. n.s. [canalis, Lat.] | ||

| + | :“1. A [[basin|bason]] of water in a garden. . . | ||

| + | :“2. Any tract or course of water made by art; as the '''canals''' in Holland.” | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | *<div id="Sheridan"></div>Sheridan, Thomas, 1789, ''A Complete Dictionary of the English Language'' (1789: n.p.)<ref>Thomas A. Sheridan, ''A Complete Dictionary of the English Language, Carefully Revised and Corrected by John Andrews. . . '', 5th ed. (Philadelphia: William Young, 1789), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/T5GU4CBQ view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| − | + | :“'''CANAL''', ka-nal'. s. . . any course of water made by art.” [[#Sheridan_cite|back up to History]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | *<div id="Repton"></div>Repton, Humphry, 1803, ''Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening'' (1803: 101, 103)<ref>Humphry Repton, ''Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening'' (London: Printed by T. Bensley for J. Taylor, 1803), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/VVQPC3BI view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| − | + | :“This explanation is necessary to justify the plan which I recommended for the '''canal''' in this flower garden: for while I should condemn a long straight line of water in an open [[park]], where every thing else is natural; I should equally object to a meandering '''canal''' or [[walk]], by the side of a long straight [[wall]], where every thing else is artificial. . . | |

| + | :“The banks of this '''canal''', or fish [[pond]], may be enriched with borders of curious flowers, and a light [[fence]] of green laths will serve to train such as require support, while it gives to the whole an air of neatness and careful attention.” [[#Repton_cite|back up to History]] | ||

| − | |||

| + | *Birch, William Russell, 1808 describing "Fountain Green Pennsylv.a the Seat of M.r S. Meeker" (1808)<ref>William Russell Birch, ''The Country Seats of the United States of North America: With Some Scenes Connected with Them'' (Springland, PA: W. Birch, 1808), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/BAIMV4GZ? view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| − | + | :"On the [[Schuylkill_River|Schuylkill]], highly favored by nature, and capable of vast improvement. Upon the half ascent of the bank from the river, the new '''canal''' will pass the house and if ever finished, will become a great ornament to the place.“ | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | [[File:1368.jpg|thumb|Fig. 15, [[J. C. Loudon]], A garden in the [[Ancient_style|ancient style]], in ''An Encyclopædia of Gardening'' (1826), p. 1009, fig. 694.]] | ||

| + | *[[J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon|Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius)]], 1826, ''An Encyclopaedia of Gardening'' (1826: 942–43)<ref>J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, ''An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening'', 4th ed. (London: Longman et al., 1826), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/KNKTCA4W/ view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| − | + | :“[Water] forms a part of every garden in the ancient style, in the various artificial characters which it there assumes of oblong '''canals''', [[pond]]s, [[basin]]s, [[cascade]]s, and ''[[jet|jeux d'eux]]'' (''fig''. 694).” [Fig. 15] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | *[[Noah Webster|Webster, Noah]], 1828, ''An American Dictionary of the English Language'' (1828: 1:n.p.)<ref>Noah Webster, ''An American Dictionary of the English Language'', 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/N7BSU467 view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| − | * Sayers, Edward, 1838, ''The American Flower Garden Companion'' ( | + | :“'''CANAL'''’, ''n''. [L. ''canalis'', a ''channel'' or ''kennel''; these being the same word differently written; Fr. ''canal''; Arm. ''can'', or ''canol''; Sp. Port. ''canal''; It. ''canale''. See. ''Cane''. It denotes a passage, from shooting, or passing.] |

| + | :“1. A passage for water; a water course; properly, a long trench or excavation in the earth for conducting water, and confining it to narrow limits; but the term may be applied to other water courses. It is chiefly applied to artificial cuts or passages for water, used for transportation; whereas ''channel'' is applicable to a natural water course.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | *Sayers, Edward, 1838, ''The American Flower Garden Companion'' (1838: 21)<ref>Edward Sayers, ''The American Flower Garden Companion, Adapted to the Northern States'' (Boston: Joseph Breck, 1838), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/GHTFN8B2 view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

:“In many cases '''canals''' have a pleasing effect as on extensive places where they are so managed as to be lost to the eye of the observer; in such cases the utility of '''canals''' is obvious to the intelligent observer.” | :“In many cases '''canals''' have a pleasing effect as on extensive places where they are so managed as to be lost to the eye of the observer; in such cases the utility of '''canals''' is obvious to the intelligent observer.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | <hr> | ||

==Images== | ==Images== | ||

| − | <gallery> | + | ===Inscribed=== |

| + | <span id="roundabout_img"></span> | ||

| + | <gallery widths="170px" heights="170px" perrow="7"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0603.jpg|Anonymous, ''Plan de la Nouvelle Orleans'', 1720. The “'''canal'''” is on the left side of the plan. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:1053.jpg|Batty Langley, “Design of a ''rural Garden'', after the new manner,” in ''New Principles of Gardening'' (1728), pl. III. “The [[Walk]]s about the two '''Canals''', and the Centers Z Z [adorned] with ''Apollo'' and the ''nine Muses''. . .” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:1378.jpg|Batty Langley, “Design of an [[Avenue]] with its [[Wilderness|Wildernesses]] on each Side,” in ''New Principles of Gardening'' (1728), pl. V. “The ''[[Avenue]]''. . . having its '''Canal''' terminated on both ends with ''Groves of Forest Trees''. . .” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:1382.jpg|Batty Langley, “An Improvement of a beautiful Garden at Twickenham,” in ''New Principles of Gardening'' (1728), pl. IX. “Canals X and Z” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:1383.jpg|Batty Langley, One of two “Designs for Gardens that lye irregularly to the grand House. . . ,” in ''New Principles of Gardening'' (1728), pl. X. "''Canal'' E E” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:1384.jpg|Batty Langley, One of two “Designs for Gardens that lye irregularly to the ground House. . . House opening to the North upon a plain [[Parterre]] of Grass,” in ''New Principles of Gardening'' (1728), pl. XI. “The '''canal''' of water” is the oblong feature in the lower half of the plan. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:1385.jpg|Batty Langley, “Design of a Small Garden Situated in a Park,” in ''New Principles of Gardening'' (1728), pl. XII. "the House. . . opens. . . to the ''South'', on a ''grand Parterre of Grass'', from which over the ''Canal''. . .” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0108.jpg|Andrew Ellicott (creator), Samuel Hill (engraver), ''Plan of the City of Washington in the Territory of Columbia'', 1792. The “'''Canal'''” is south of “GeorgeTown.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0728.jpg|William Russell Birch, ''Plan of Springland'', c. 1800, in Emily T. Cooperman and Lea Carson Sherk, ''William Birch: Picturing the American Scene'' (2011), 206, fig. 117. The “'''canal'''” is on the middle right side of the plan. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0594.jpg|[[Benjamin Henry Latrobe]], ''Section of the northern course of the '''canal''' from the tide in the Elk River at Frenchtown to the forked [oak] in Mr. Rudulph’s swamp'', 1803. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:1133.jpg|Anonymous, Moore and Jones (engravers), ''District of Columbia and Vicinity'', c. 1804. The “'''canal'''” is in the middle of the plan, below the "Capitol.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0871.jpg|[[Benjamin Henry Latrobe]], ''Plan of the Washington '''Canal''', No. 1'', February 5, 1804, in John W. Reps, ''Monumental Washington, The Planning and Development of the Capital Center'' (1967), fig. 17. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0496.jpg|[[Charles Fraser]], ''A Bason and Storehouse Belonging to the Santee '''Canal''' in 1803'', 1805. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0035.jpg|[[Benjamin Henry Latrobe]], Plan of the Capitol grounds, 1815. The “'''canal'''” runs through the middle of the plan. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0414.jpg|[[Benjamin Henry Latrobe]], ''Plan of the west end of the public appropriation in the city of Washington, called the [[Mall]], as proposed to be arranged for the site of the university'', 1816. The “'''canal'''” is in the upper right of the plan. | ||

| − | Image: | + | Image:0039.jpg|Charles Bulfinch, ''Plan of [[Public garden/Public ground|Grounds]] adjacent to the Capitol'', 1822. "Proposed alteration of the '''Canal'''" |

| + | |||

| + | Image:0433.jpg|[[Robert Mills]], ''Plan of the Washington '''Canal''''', 1831. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0024.jpg|Henry Schenck Tanner, ''City of Washington'', c. 1836. A '''canal''' is southwest of Virginia [[Avenue]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0033.jpg|[[Robert Mills]], ''Plan of the [[Mall]]'', Washington, DC, 1841. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0034.jpg|[[Robert Mills]], Alternative plan for the grounds of the National Institution, 1841. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0568.jpg|William Keenan, ''Plan of the City and Neck of Charleston, SC'', September 1844. “'''Canal'''” is on the left side of the plan. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:1159.jpg|Noyes, C. J., ''A Plan of Brunswick Village'', September 1846. "Proposed '''Canal''' for Mills" at center of plan. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0567.jpg|Sam A. Gilbert, ''A Plan of the City of Charleston'', 1849. “'''Canal'''” is on the left side of the plan. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0352.jpg|[[A. J. Downing]], ''Suspension bridge across the Canal'' [proposed], 1851. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:1967.jpg|[[A. J. Downing]], ''Plan showing proposed method of laying out the [[Public_garden|public grounds]] at Washington'', 1851. “'''Canal'''” is north of the Mall. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0023.jpg|[[A. J. Downing]], ''Plan Showing Proposed Method of Laying Out the Public Grounds at Washington'', 1851. Manuscript copy by Nathaniel Michler, 1867. “'''Canal'''” is north of the [[Mall]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image: 0023_detail5.jpg|[[A. J. Downing]], ''Plan Showing Proposed Method of Laying Out the [[Public_ground|Public Grounds]] at Washington'' [detail], 1851. Manuscript copy by Nathaniel Michler, 1867. | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Associated=== | ||

| + | <gallery widths="170px" heights="170px" perrow="7"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0056.jpg|[[John Bartram|John]] or [[William Bartram]], "A Draught of [[Bartram_Botanic_Garden_and_Nursery|John Bartram’s House and Garden]] as it appears from the River", 1758. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0031.jpg|Andrew Ellicott, ''Plan of the City of Washington in the Territory of Columbia'', 1795. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0731.jpg|William Russell Birch, ''[[View]] from Springland'', c. 1808. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0302.jpg|William Russell Birch, “Fountain Green Pennsylv.<sup>a</sup> the [[Seat]] of M.<sup>r</sup> S. Meeker,” in ''The Country [[Seat]]s of the United States'' (1808), pl. 8. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0302b.jpg|William Russell Birch, “Fountain Green Pennsylv.<sup>a</sup> the [[Seat]] of M.<sup>r</sup> S. Meeker,” in ''The Country [[Seat]]s of the United States'' (1808), pl. 8. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0716.jpg|Alvan Fisher, ''The Vale'', 1820–25. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:1176.jpg|Eliza Susan Quincy, ''[[View]] of the [[seat]] of Edmund Quincy Esqr.'', 1822. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:1994.jpg|Thomas Doughty, ''[[View]] of the Fairmount Waterworks, Philadelphia, from the Opposite Side of the [[Schuylkill River]]'', c. 1824–26. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:1368.jpg|[[J. C. Loudon]], A garden in the [[Ancient_style|ancient style]], in ''An Encyclopædia of Gardening'' (1826), p. 1009, fig. 694. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0289.jpg|John William Hill, ''[[View]] on the Erie Canal'', 1829. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0537.jpg|Tucker Factory, Pair of [[vase]]s with [[view]]s of the Fairmount Waterworks, c. 1830. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0110.jpg|Joseph Goldsborough Bruff (artist), Edward Weber & Co. (lithographer), ''Elements of National Thrift and Empire'', c. 1847. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0025.jpg|Robert P. Smith, ''[[View]] of Washington'', c. 1850. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0111.jpg|Seth Eastman, ''[[Washington_Monument_(Washington,_DC)|Washington’s Monument]], Under Construction'', November 16, 1851. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0042.jpg|Benjamin Franklin Smith Jr., ''Washington, DC with projected improvements'', c. 1852. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0041.jpg|Anonymous, Capitol Under Construction, [[View]] Looking East Toward the Capitol From Third Street Vicinity, July 1860. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </gallery> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Attributed=== | ||

| + | <gallery widths="170px" heights="170px" perrow="7"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0283.jpg|Anonymous, George Hayward (engraver), ''“The Duke’s Plan,” a Description of the Towne of Mannados: or New Amsterdam as it was in September 1661'', [1664] 1859. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:1377.jpg|Batty Langley, Garden with a '''canal''', in ''New Principles of Gardening'' (1728), pl. IV. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0037.jpg|[[Charles Willson Peale]], ''William Paca'', 1772. The canal is crossed by white bridge seen on right. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0881.jpg|Anonymous, ''Plan de la ville et environs de Williamsburg en Virginie, America'', 1782. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0048.jpg|John Nancarrow, "Plan of the [[Seat]] of John Penn, jun'r: Esqr: in Blockley Township and County of Philadelphia", c. 1785. Canal is the stream of water in the center of the image. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0300.jpg|Thomas Birch, ''Fairmount Water Works'', 1821. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0288.jpg|George Cooke (artist), W. J. Bennett (engraver), ''Richmond, From the Hill Above the Waterworks'', 1834. | ||

| + | |||

| + | File:2144.jpg|William Southgate Porter, ''Panorama of Fairmount'', May 22, 1848. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0459.jpg|Jenny Emily Snow, attr., ''Fairmount Park Waterworks'', c. 1850. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </gallery> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <hr> | ||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| Line 151: | Line 292: | ||

[[Category: Keywords]] | [[Category: Keywords]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Water Features]] | ||

Latest revision as of 10:41, April 6, 2021

See also: Basin

History

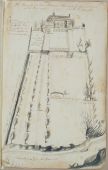

The canal was an artificial waterway built for navigation, irrigation, and ornamentation. In general, it was a channel, usually set into the ground, with parallel walls made of earth, stone, or brick. Canals varied widely in size: from broad navigable examples, such as the Erie and the Chesapeake & Ohio, to smaller garden ones such as that depicted in a sketch of the seat of Edmund Quincy [See Fig. 8] in Massachusetts. Within the garden, canals could be straight, an idea promoted by treatise author Humphry Repton (1803), or they could meander, as at the Vale, in Waltham, Massachusetts [See Fig. 11]. In addition to the main channel, garden canals sometimes widened to form a fishpond emptied into a nearby river or pond, or filled a basin as in Benjamin Henry Latrobe's plan of an aqueduct [Fig. 1] (see Basin).

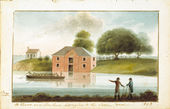

Canals were an element of American landscape design as early as the beginning of the 18th century, as attested to by Hugh Jones's 1722 description of the Governor’s Palace in Williamsburg, Virginia (view text) [Fig. 2]. The chronology of American garden canal construction, at least as recorded in garden descriptions, suggests that the popularity of building canals in residential gardens dwindled in the 19th century. They continued to be utilized in public landscape designs, however, as at the Columbian Institute in Washington, DC Although images of navigable canals, such as the Erie Canal, were popular symbols during this time of America’s burgeoning prosperity and technological achievement [Fig. 3], views of private garden canals were rare.

In gardens, canals were less common than still-water features (such as fishponds and pools), most likely because canals required both a continuous water source and a relatively large amount of space. The feasibility of such a canal was obviously dependent upon the availability of water, and, not unexpectedly, garden canals were more common in coastal or riverine areas such as Charleston; Williamsburg; Washington, DC; and Philadelphia.

Like other water features, canals provided a source of fresh food. The canal of Edmund Quincy supplied eel, Alexander Gordon's canal was stocked with fish, and the canal of Thomas Brattle was noted for its waterfowl. Canals also provided irrigation, ice, and, if large enough, offered opportunities for boating [Fig. 4]. In low-lying areas and in examples such as Garden’s waterway (which was fed by fresh springs), the canal also offered drainage for excess water. Like other water features, they provided a garden with the animation of moving or rippling water, the cooling effect of evaporation, the visual interest of reflective surfaces, and habitats for swans and other ornamental birds. The slow flow and placid surface of a canal might stand in contrast to the burbling course of a stream or the dynamic rush of a cascade. With a border of flowers, a canal might, as Repton (1803) suggested, lend “to the whole an air of neatness and careful attention” (view text).

Urban canals, indicated on city plans, were built as commercial transportation routes, but these canals were also embraced in efforts to create healthful, recreational areas for city dwellers. Banks along some navigable canals were ornamented with walks, benches, and fences. In other cases, canals constructed for commercial or navigational purposes were incorporated in public landscape design schemes, as at Fairmount Park in Philadelphia [Fig. 5] and the national Mall in Washington, DC [Fig. 6]. At Fairmount Park, which is depicted on a painted vase [Fig. 7], the canal for the pumping station became a popular promenade. In Washington, designers such as Pierre-Charles L'Enfant, Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Charles Bulfinch, and Robert Mills used the canal as an integral element of their plans for the national Mall, routing it to accentuate the view of the capitol and ornamenting it with bridges and walks. Latrobe’s Plan of the Capitol (1815) incorporated a waterway he referred to as a Canal [See Fig. 10]. L'Enfant even proposed an ambitious scheme to have water run under the U.S. Capitol and then cascade into the canal below, at the level of the Mall.

Samuel Johnson's 1755 definition of a canal as a “course of water made by art” (view text), and Thomas Sheridan's 1789 definition () are particularly telling for the canal’s significance in a landscape-design context. The use of art and water points to the canal’s combination of the artificial and the natural, a juxtaposition that is at the essence of any garden. A canal, in particular, resonates with the theme; it carries water, a basic element in the garden, yet the hand of its human creator is obvious in the contrived regularity of its construction. Dr. Alexander Garden (1754), in reference to Bartram’s Garden, noted that the botanist’s enthusiastic attempt to put the stamp of art on every natural feature, culminated in a design in which “[e]very run of water, [was] a Canal” (view text).

—Elizabeth Kryder-Reid

Texts

Usage

- Jones, Hugh, 1722, describing the Governor’s Palace, Williamsburg, VA (1956: 70)[1]

- “. . . the Palace or Governor’s House, a magnificent structure, built at the publick expence, finished and beautified with gates, fine gardens, offices, walks, a fine canal, orchards, etc. with a great number of the best arms nicely posited, by the ingenious contrivance of the most accomplished Colonel Spotswood.” back up to History

- Hamilton, Alexander, July 17, 1744, describing Malbone Hall, country seat of Godfrey Malbone, Newport, RI (1948: 103)[2]

- “This house makes a grand show att a distance but is not extraordinary for the architecture, being a clumsy Dutch modell. Round it are pritty gardens and terrasses with canals and basons for water.”

- Anonymous, May 22, 1749, describing the kitchen garden of Alexander Garden, Charleston, SC (South Carolina Gazette)

- “. . . at the end of which is a canal supplied with fresh springs of water, about 300 feet long, with fish.”

- Goelet, Capt. Francis, c. 1750, describing the residence and garden of Edmund Quincy, Boston, MA (quoted in Pearson 1980: 6)[3]

- “. . . about Ten Yards from the House is a Beautiful Cannal, which is Supplyd by a Brook which is well Stockt with Fine Silver Eels, we Cought a fine Parcell and carried them Home and had them drest for Supper, the House has a Beautifull Pleasure Garden Adjoyning it, and on the Back Part the Building is a Beautiful Orchard with fine fruit trees, etc.” [Fig. 8]

- Garden, Dr. Alexander, 1754, in a letter to Cadwallader Colden, describing Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery, vicinity of Philadelphia, PA (Colden 1920: 4: 472)[4]

- “. . . he disdains to have a garden less than Pensylvania & Every den is an Arbour, Every run of water, a Canal, & every small level Spot a Parterre.” [Fig. 9] back up to History

- Shippen, Thomas Lee, December 31, 1783, describing Westover, seat of William Byrd III, on the James River, VA (1952: n.p.)[5]

- “These meadows well watered with canals, which communicate with each other across the road give occasion every 50 yards for a bridge; and between every two bridges are two gates one on each side the road.”

- L'Enfant, Pierre-Charles, June 22, 1791, describing his plans for Washington, DC (quoted in Caemmerer 1950: 152–53)[6]

- “a canal being easy to open from the eastern branch and to be lead across the first settlement and carried toward the mouth of the [T]iber where it will again give an issue into the Potowmack and at a distance not to far off for to admit the boats from the grand navigation canal from getting in, will undoubtedly facilitate a conveyance most advantageous to trading Interest. . .

- “I propose in this map, of leting the [T]iber return in its proper channel by a fall which issuing from under the base of the Congress building may there form a cascade of forty feet heigh [sic] or more than one hundred waide [sic] which would produce the most happy effect in rolling down to fill up the canall [sic] and discharge itself in the Potowmack of which it would then appear as the main spring when seen through that grand and majestic avenue intersecting with the prospect from the palace.” [Fig. 10]

- Bentley, William, October 4, 1792, describing the residence of Thomas Brattle, Cambridge, MA (1962: 1:398)[7]

- “I visited Mr Brattle’s Gardens, &c. at Cambridge. We first saw the fountain & canal opposite to his House, & the walk on the side of another canal in the road, flowing under an arch & in the direction of the outer fence. There is another canal which communicates with a beautiful pool in the park & place for his wild fowl.”

- La Rochefoucauld Liancourt, François Alexandre-Frédéric, duc de, 1799, describing Middleton Place, seat of Henry Middleton, near Charleston, SC (1800: 2:438)[8]

- “A peculiar feature of the situation is this, that the river, which flows in a circuitous course, until it reaches this point, forms here a wide, beautiful canal, pointing straight to the house.”

- Scott, Joseph, 1806, describing Fairmount Waterworks, Philadelphia, PA (1806: 25–26)[9]

- “The water-works of Philadelphia are the most extensive of their kind of any in America. They consist of a basin, excavated, partly in the bed of the river Schuylkill, three feet deeper than low-water mark. . . The basin extends easterly to high-water mark, where it is secured by another wall and sluice, admitting the water to a canal 40 feet wide, and 200 feet long. From the east end of the canal, a subteraneous tunnel, conveys the water underneath the edge of the high bank, or plain, upon which the city is built. The canal and tunnel are hewn out of the solid granite, and their bottoms are three feet below low-water mark. The east end of the tunnel enters a well, sunk from the top of the bank. The well receives the waters of the Schulkill, from the basin, by means of the canal.”

- Ripley, Samuel, 1815, describing the Vale, estate of Theodore Lyman, Waltham, MA (1815: 272)[10]

- “Through the lawn, in front of the mansion house, which is large and handsome, runs Beaver Brook, which it there formed into a serpentine canal, and over which is erected a bridge of three arches, made of the Chelmsford white stone, which is both an ornament to the place, and a specimen of correct taste and workmanship.”

- Columbian Institute, 1823, describing the Columbian Institute, Washington, DC (quoted in O’Malley 1989: 127)[11]

- “The canal that surrounds it is 15 feet wide and 2 1/2 feet deep.”

- Commissioner of Public Buildings, June 9, 1827, describing the Columbian Institute, Washington, DC (quoted in O’Malley 1989: 133)[11]

- “The new section of the Washington Canal was laid out along a line drawn through the middle of the Capitol and of the Mall. The pathway, canal and plantation in the garden do not coincide with this line, but diverge from it at an acute angle.” [Fig. 12]

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1851, describing plans for improving the public grounds in Washington, DC (quoted in Washburn 1967: 55)[12]

- “5th: Fountain Park

- “This Park would be chiefly remarkable for its water features. The Fountain would be chiefly supplied from a basin in the Capitol. The Pond or lake might either be formed from the overflow of this fountain, or from a filtering drain from the canal. The earth that would be excavated to form this pond is needed to fill up low places now existing in this portion of the grounds.”

Citations

- Langley, Batty, 1728, New Principles of Gardening (1728; repr., 1982: xii–xiii)[13]

- “Plate IX. is an improvement of a beautiful Garden at Twickenham, situated on the River Thames, which passes by the Line E F, and has a free communication with the Canals X and Z. . . [Fig. 13]

- “Plates X and XI, are Designs for gardens that lye [sic] irregularly to the grand House. In Plate X, the House opens to the North upon the Park A, to the East upon Court B, to the South upon the Parterre of Grass and Water C; and Lastly to the West upon the circular Bason D, from which leads a pleasant Avenue Z X. The Mount F, is raised with the Earth that came out of the Canal E E, and its Slope H is planted with Hedges of different Ever-Greens, that rising behind one another of different Colours have a very good Effect, being view'd form M. I,I are contracts Walks leading up to the Mount . . . [Fig. 14]

- “Plate XII is the Design of a small Garden situated in a Park, where the House to the North opens upon a noble circular Basin of Water B, in the Park, and to the South, on a grand Parterre of Grass, from which over the Canal you have a boundless View into the Country.”

- Chambers, Ephraim, 1741, Cyclopaedia (1741: 1:n.p.)[14]

- “GARDEN. . .

- “The chief furniture of pleasure gardens are, parterres, vistas, glades, groves, compartiments, quincunces, verdant halls, arbour work, mazes, labyrinths, fountains, cabinets, cascades, canals, terraces, &c.”

- Johnson, Samuel, 1755, A Dictionary of the English Language (1755: 1:n.p.),[15] back up to History

- “CANA'L. n.s. [canalis, Lat.]

- “1. A bason of water in a garden. . .

- “2. Any tract or course of water made by art; as the canals in Holland.”

- Sheridan, Thomas, 1789, A Complete Dictionary of the English Language (1789: n.p.)[16]

- “CANAL, ka-nal'. s. . . any course of water made by art.” back up to History

- Repton, Humphry, 1803, Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1803: 101, 103)[17]

- “This explanation is necessary to justify the plan which I recommended for the canal in this flower garden: for while I should condemn a long straight line of water in an open park, where every thing else is natural; I should equally object to a meandering canal or walk, by the side of a long straight wall, where every thing else is artificial. . .

- “The banks of this canal, or fish pond, may be enriched with borders of curious flowers, and a light fence of green laths will serve to train such as require support, while it gives to the whole an air of neatness and careful attention.” back up to History

- Birch, William Russell, 1808 describing "Fountain Green Pennsylv.a the Seat of M.r S. Meeker" (1808)[18]

- "On the Schuylkill, highly favored by nature, and capable of vast improvement. Upon the half ascent of the bank from the river, the new canal will pass the house and if ever finished, will become a great ornament to the place.“

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826: 942–43)[19]

- “[Water] forms a part of every garden in the ancient style, in the various artificial characters which it there assumes of oblong canals, ponds, basins, cascades, and jeux d'eux (fig. 694).” [Fig. 15]

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828: 1:n.p.)[20]

- “CANAL’, n. [L. canalis, a channel or kennel; these being the same word differently written; Fr. canal; Arm. can, or canol; Sp. Port. canal; It. canale. See. Cane. It denotes a passage, from shooting, or passing.]

- “1. A passage for water; a water course; properly, a long trench or excavation in the earth for conducting water, and confining it to narrow limits; but the term may be applied to other water courses. It is chiefly applied to artificial cuts or passages for water, used for transportation; whereas channel is applicable to a natural water course.”

- Sayers, Edward, 1838, The American Flower Garden Companion (1838: 21)[21]

- “In many cases canals have a pleasing effect as on extensive places where they are so managed as to be lost to the eye of the observer; in such cases the utility of canals is obvious to the intelligent observer.”

Images

Inscribed

Batty Langley, “Design of a rural Garden, after the new manner,” in New Principles of Gardening (1728), pl. III. “The Walks about the two Canals, and the Centers Z Z [adorned] with Apollo and the nine Muses. . .”

Batty Langley, “Design of an Avenue with its Wildernesses on each Side,” in New Principles of Gardening (1728), pl. V. “The Avenue. . . having its Canal terminated on both ends with Groves of Forest Trees. . .”

Batty Langley, One of two “Designs for Gardens that lye irregularly to the ground House. . . House opening to the North upon a plain Parterre of Grass,” in New Principles of Gardening (1728), pl. XI. “The canal of water” is the oblong feature in the lower half of the plan.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Section of the northern course of the canal from the tide in the Elk River at Frenchtown to the forked [oak] in Mr. Rudulph’s swamp, 1803.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Plan of the Washington Canal, No. 1, February 5, 1804, in John W. Reps, Monumental Washington, The Planning and Development of the Capital Center (1967), fig. 17.

Charles Fraser, A Bason and Storehouse Belonging to the Santee Canal in 1803, 1805.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Plan of the Capitol grounds, 1815. The “canal” runs through the middle of the plan.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Plan of the west end of the public appropriation in the city of Washington, called the Mall, as proposed to be arranged for the site of the university, 1816. The “canal” is in the upper right of the plan.

Charles Bulfinch, Plan of Grounds adjacent to the Capitol, 1822. "Proposed alteration of the Canal"

Robert Mills, Plan of the Washington Canal, 1831.

Henry Schenck Tanner, City of Washington, c. 1836. A canal is southwest of Virginia Avenue.

Robert Mills, Plan of the Mall, Washington, DC, 1841.

Robert Mills, Alternative plan for the grounds of the National Institution, 1841.

A. J. Downing, Suspension bridge across the Canal [proposed], 1851.

A. J. Downing, Plan showing proposed method of laying out the public grounds at Washington, 1851. “Canal” is north of the Mall.

A. J. Downing, Plan Showing Proposed Method of Laying Out the Public Grounds at Washington, 1851. Manuscript copy by Nathaniel Michler, 1867. “Canal” is north of the Mall.

A. J. Downing, Plan Showing Proposed Method of Laying Out the Public Grounds at Washington [detail], 1851. Manuscript copy by Nathaniel Michler, 1867.

Associated

John or William Bartram, "A Draught of John Bartram’s House and Garden as it appears from the River", 1758.

William Russell Birch, View from Springland, c. 1808.

Thomas Doughty, View of the Fairmount Waterworks, Philadelphia, from the Opposite Side of the Schuylkill River, c. 1824–26.

J. C. Loudon, A garden in the ancient style, in An Encyclopædia of Gardening (1826), p. 1009, fig. 694.

John William Hill, View on the Erie Canal, 1829.

Robert P. Smith, View of Washington, c. 1850.

Seth Eastman, Washington’s Monument, Under Construction, November 16, 1851.

Anonymous, Capitol Under Construction, View Looking East Toward the Capitol From Third Street Vicinity, July 1860.

Attributed

Charles Willson Peale, William Paca, 1772. The canal is crossed by white bridge seen on right.

John Nancarrow, "Plan of the Seat of John Penn, jun'r: Esqr: in Blockley Township and County of Philadelphia", c. 1785. Canal is the stream of water in the center of the image.

Notes

- ↑ Hugh Jones, The Present State of Virginia, From Whence Is Inferred a Short View of Maryland and North Carolina, ed. Richard L. Morton (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1956), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alexander Hamilton, Gentleman’s Progress: The Itinerarium of Dr. Alexander Hamilton, 1744, ed. Carl Bridenbaugh (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1948), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Danella Pearson, “Shirley-Eustis House Landscape History,” Old-Time New England 70 (1980): 1–16, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Cadwaller Colden, The Letters and Papers of Cadwallader Colden, 9 vols. (New York: New-York Historical Society, 1918–37), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Lee Shippen, Westover Described in 1783: A Letter and Drawing Sent by Thomas Lee Shippen, Student of Law in Williamsburg, to His Parents in Philadelphia (Richmond, VA: William Byrd Press, 1952), view on Zotero.

- ↑ H. Paul Caemmerer, The Life of Pierre-Charles L’Enfant, Planner of the City Beautiful, The City of Washington (Washington, DC: National Republic Publishing Company, 1950), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Bentley, The Diary of William Bentley, D.D., Pastor of the East Church, Salem, Massachusetts, 2 vols. (Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1962), view on Zotero.

- ↑ François-Alexandre-Frédéric, duc de la Rochefoucauld-Liancourt, Travels through the United States of North America, the Country of the Iroquois, and Upper Canada, in the Years 1795, 1796, and 1797, ed. Brisson Dupont and Charles Ponges, trans. H. Newman, 2nd ed., 4 vols. (London: R. Philips, 1800), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Joseph Scott, A Geographical Description of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia: Printed by R. Cochran, 1806), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel Ripley, “A Topographical and Historical Description of Waltham, in the County of Middlesex, Jan. 1, 1815,” Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society 3 (January 1815): 261–84, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Therese O’Malley, “Art and Science in American Landscape Architecture: The National Mall, Washington, DC 1791–1852" (PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1989), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Wilcomb E. Washburn, "Vision of Life for the Mall,” AIA Journal 47 (1967): 52–59, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Batty Langley, New Principles of Gardening, or The Laying Out and Planting Parterres, Groves, Wildernesses, Labyrinths, Avenues, Parks, &c (London: A. Bettesworth and J. Batley, etc., 1728; repr., London: Garland, 1982), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Ephraim Chambers, Cyclopaedia, or An Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences . . . , 5th ed., 2 vols. (London: D. Midwinter et al., 1741–43), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language: In Which the Words Are Deduced from the Originals and Illustrated in the Different Significations by Examples from the Best Writers, 2 vols. (London: W. Strahan for J. and P. Knapton, 1755), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas A. Sheridan, A Complete Dictionary of the English Language, Carefully Revised and Corrected by John Andrews. . . , 5th ed. (Philadelphia: William Young, 1789), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Humphry Repton, Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (London: Printed by T. Bensley for J. Taylor, 1803), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Russell Birch, The Country Seats of the United States of North America: With Some Scenes Connected with Them (Springland, PA: W. Birch, 1808), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, 4th ed. (London: Longman et al., 1826), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Edward Sayers, The American Flower Garden Companion, Adapted to the Northern States (Boston: Joseph Breck, 1838), view on Zotero.