Difference between revisions of "Charles Willson Peale"

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

Peale’s three years abroad—from 1767 to 1770—enhanced his artistic skill and reputation, and his career continued to grow following his return from abroad. In 1776 he relocated his growing family from Maryland to Philadelphia, then the most cosmopolitan city in the British colonies, to develop an expanded network of patronage.<ref>Charles Coleman Sellers, ''Charles Willson Peale'' (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1969), 119–20, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/PWCSA5AD view on Zotero]. Peale would marry three times and have eighteen children, though only eleven of them would live to adulthood. See Kate Nearpass Ogden, “The Peale Family of Painters,” in ''The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia'', http://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/peale-family-of-painters/.</ref> There he painted portraits of the city’s political figures and became politically engaged himself: he was a lieutenant in the Philadelphia militia during the American Revolution, and also fought in the Continental Army under General [[George Washington]].<ref>Ward 2004, 72–73, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/BCITM4SK view on Zotero].</ref> He would play an important role in developing Washington’s political image through the seventy portraits he made, beginning in 1772, of the noted military figure and first U.S. President.<ref>Sellers 1969, 99–100, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/PWCSA5AD view on Zotero]; Ward 2004, 45–46, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/BCITM4SK view on Zotero].</ref> | Peale’s three years abroad—from 1767 to 1770—enhanced his artistic skill and reputation, and his career continued to grow following his return from abroad. In 1776 he relocated his growing family from Maryland to Philadelphia, then the most cosmopolitan city in the British colonies, to develop an expanded network of patronage.<ref>Charles Coleman Sellers, ''Charles Willson Peale'' (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1969), 119–20, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/PWCSA5AD view on Zotero]. Peale would marry three times and have eighteen children, though only eleven of them would live to adulthood. See Kate Nearpass Ogden, “The Peale Family of Painters,” in ''The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia'', http://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/peale-family-of-painters/.</ref> There he painted portraits of the city’s political figures and became politically engaged himself: he was a lieutenant in the Philadelphia militia during the American Revolution, and also fought in the Continental Army under General [[George Washington]].<ref>Ward 2004, 72–73, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/BCITM4SK view on Zotero].</ref> He would play an important role in developing Washington’s political image through the seventy portraits he made, beginning in 1772, of the noted military figure and first U.S. President.<ref>Sellers 1969, 99–100, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/PWCSA5AD view on Zotero]; Ward 2004, 45–46, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/BCITM4SK view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| − | [[File:William_Bartram.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 2, | + | [[File:William_Bartram.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 2, Charles Willson Peale, ''William Bartram'', c. 1808.]] |

[[File:The Gigantic Mastodon.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 3, Titian Ramsay Peale, ''The Gigantic Mastodon'', 1821.]] | [[File:The Gigantic Mastodon.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 3, Titian Ramsay Peale, ''The Gigantic Mastodon'', 1821.]] | ||

As the Revolutionary War drew to a close, Peale began a series of portraits of statesmen, designers, and naturalists—including [[Thomas Jefferson]], [[Benjamin Henry Latrobe]], [[William Bartram]], among many others—who he believed would shape the future of the new nation [Fig. 2].<ref>Ward 2004, 83, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/BCITM4SK view on Zotero]. Ward describes this series as a “pantheon that would perpetuate American republicanism.”</ref> Many of these figures were members of the American Philosophical Society, one of Philadelphia’s first learned societies, to which Peale had likewise been elected in 1786.<ref>Sellers 1969, 214, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/PWCSA5AD view on Zotero].</ref> Their portraits became a key feature of his Philadelphia Museum, which he opened following his official “retirement” from painting in 1794 [Fig. 2]. The institution, a “world in miniature,” married Peale’s keen interest in natural history with his passion for art. Developed to enlighten and educate the public, the museum’s central gallery or “Long Room” featured preserved zoological specimens arranged in discrete dioramas according to the Linnaean system—the prevailing taxonomy of the second half of the 18th century—surmounted by Peale’s portraits of American patriots (see Fig. 1).<ref>Sidney Hart and David C. Ward, “Peale’s Philadelphia Museum,” in Lillian B. Miller and David C. Ward, eds., ''New Perspectives on Charles Willson Peale'' (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1991), 222–23, 233, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/XDT5MHM3 view on Zotero]. Though Peale would continue to paint in the coming years, his output was less prodigious; see Sellers 1969, 262, for Peale’s notice of his retirement in ''Claypoole’s Daily Advertiser'' (April 24, 1794), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/PWCSA5AD view on Zotero].</ref> Following Peale’s ambitious exhumation of mastodon bones in Newburgh, New York, in 1801, he included the reassembled skeleton in his galleries [Fig. 3]. | As the Revolutionary War drew to a close, Peale began a series of portraits of statesmen, designers, and naturalists—including [[Thomas Jefferson]], [[Benjamin Henry Latrobe]], [[William Bartram]], among many others—who he believed would shape the future of the new nation [Fig. 2].<ref>Ward 2004, 83, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/BCITM4SK view on Zotero]. Ward describes this series as a “pantheon that would perpetuate American republicanism.”</ref> Many of these figures were members of the American Philosophical Society, one of Philadelphia’s first learned societies, to which Peale had likewise been elected in 1786.<ref>Sellers 1969, 214, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/PWCSA5AD view on Zotero].</ref> Their portraits became a key feature of his Philadelphia Museum, which he opened following his official “retirement” from painting in 1794 [Fig. 2]. The institution, a “world in miniature,” married Peale’s keen interest in natural history with his passion for art. Developed to enlighten and educate the public, the museum’s central gallery or “Long Room” featured preserved zoological specimens arranged in discrete dioramas according to the Linnaean system—the prevailing taxonomy of the second half of the 18th century—surmounted by Peale’s portraits of American patriots (see Fig. 1).<ref>Sidney Hart and David C. Ward, “Peale’s Philadelphia Museum,” in Lillian B. Miller and David C. Ward, eds., ''New Perspectives on Charles Willson Peale'' (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1991), 222–23, 233, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/XDT5MHM3 view on Zotero]. Though Peale would continue to paint in the coming years, his output was less prodigious; see Sellers 1969, 262, for Peale’s notice of his retirement in ''Claypoole’s Daily Advertiser'' (April 24, 1794), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/PWCSA5AD view on Zotero].</ref> Following Peale’s ambitious exhumation of mastodon bones in Newburgh, New York, in 1801, he included the reassembled skeleton in his galleries [Fig. 3]. | ||

Revision as of 13:53, August 9, 2018

Charles Willson Peale (April 15, 1741–February 22, 1827) was an American artist, naturalist, and museum proprietor [Fig. 1]. He fought in the Revolutionary War under George Washington, of whom he made numerous portraits, and corresponded with Thomas Jefferson regarding their shared interest in natural history, agriculture, and landscape design. Their correspondence informed the development of his country retreat, Belfield, just outside Philadelphia.

History

Born in straitened circumstances in Chester, Maryland, Charles Willson Peale initially pursued a variety of careers—saddler, harness-maker, upholsterer, and silversmith—before landing on the profession by which he would make his livelihood: portrait painter.[1] He began creating portraits of Maryland’s colonial elite, who later underwrote Peale’s travel to England. In the absence of art academies in the colonies, an academic art education required travel abroad. Supported by this group of wealthy Marylanders, thanks to his wife’s well-connected family, Peale sailed for London to study with the expatriate American artist, Benjamin West.[2]

Peale’s three years abroad—from 1767 to 1770—enhanced his artistic skill and reputation, and his career continued to grow following his return from abroad. In 1776 he relocated his growing family from Maryland to Philadelphia, then the most cosmopolitan city in the British colonies, to develop an expanded network of patronage.[3] There he painted portraits of the city’s political figures and became politically engaged himself: he was a lieutenant in the Philadelphia militia during the American Revolution, and also fought in the Continental Army under General George Washington.[4] He would play an important role in developing Washington’s political image through the seventy portraits he made, beginning in 1772, of the noted military figure and first U.S. President.[5]

As the Revolutionary War drew to a close, Peale began a series of portraits of statesmen, designers, and naturalists—including Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Henry Latrobe, William Bartram, among many others—who he believed would shape the future of the new nation [Fig. 2].[6] Many of these figures were members of the American Philosophical Society, one of Philadelphia’s first learned societies, to which Peale had likewise been elected in 1786.[7] Their portraits became a key feature of his Philadelphia Museum, which he opened following his official “retirement” from painting in 1794 [Fig. 2]. The institution, a “world in miniature,” married Peale’s keen interest in natural history with his passion for art. Developed to enlighten and educate the public, the museum’s central gallery or “Long Room” featured preserved zoological specimens arranged in discrete dioramas according to the Linnaean system—the prevailing taxonomy of the second half of the 18th century—surmounted by Peale’s portraits of American patriots (see Fig. 1).[8] Following Peale’s ambitious exhumation of mastodon bones in Newburgh, New York, in 1801, he included the reassembled skeleton in his galleries [Fig. 3].

Peale oversaw the Philadelphia Museum until 1810, when he passed its directorship to his son Rubens and removed to Belfield, his country retreat outside Philadelphia. Though retired, his entrepreneurial spirit remained active and, as with his museum, he endeavored to merge his scientific and aesthetic interests in the farm’s design. Belfield was intended to be functional and profitable as well as beautiful: Peale cultivated clover, corn, buckwheat, and oats, as well as ornamental plants, and featured a number of garden structures—such as a Chinese summerhouse, a temple, and an obelisk [Figs. 4 and 5]—drawn from such landscape design sources as Batty Langley’s City and Country Builder’s Treasury (1740) and George Gregory’s Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (1807).[9] Peale sought both plants and advice for Belfield from the rich network of botanists and plant enthusiasts in the early republic, such as the nurseryman Bernard M’Mahon; the botanist, Benjamin Smith Barton; and William Hamilton, the proprietor of The Woodlands.[10] Belfield was essentially an ornamental farm or ferme ornée, much like Jefferson’s Monticello, and Peale often corresponded with the former president about his farm’s progress and considerable challenges.[11]

Disappointed by his struggles to make Belfield profitable, Peale returned in 1821 to Philadelphia, where he set about creating a series of portraits, this time of himself. He portrayed himself as painter, as naturalist, and—in his 1822 opus, The Artist in His Museum—as entrepreneurial showman who could craft knowledge and order from the raw materials of the natural world (see Fig. 1).[12] This series of portraits would constitute Peale’s final efforts at solidifying his legacy as an enlightened American patriot before his illness and death in 1827.[13]

—Elizabeth Athens

Texts

- Peale, Charles Willson, February 15, 1772, describing a portrait of William Paca, including his garden in Annapolis, MD (Miller et al., eds., 1983: 1:113)[14]

- “I have spent some time about Mr. Paca’s whole lenght [sic] . . . if you remember the action he is resting on a pedestal on which I have introduced the Bust of Tully but believe [I] will be obliged to put some other in its [ ] place in the distance is a View of his Summer house.” [Fig. 6]

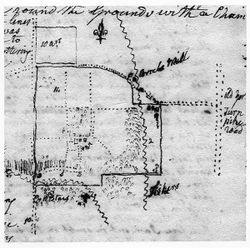

- Peale, Charles Willson, December 8, 1783, describing his triumphal arch erected in Philadelphia (quoted in Sellers 1969: 196)[15]

- “I am at this time employed in painting a transparent triumphal Arch for the Public rejoicings on the peace, and very much hurried.” [Fig. 7]

- Peale, Charles Willson, June 1788, describing Annapolis, MD (Miller et al., eds., 1983: 1:498)[14]

- “being invited to dine with the fish Club, I took my Gun for further Amusement; the club had a marqui fixed opposite the Cool Spring (bath House) on the other side of the creek. They have skittle Ground and qu[o]ites to amuse themselves.”

- Peale, Charles Willson, June 12, 1804, describing the Carroll Garden, Annapolis, Md. (Miller et al., eds., 1988: 2:704)[14]

- “at each end of the wall is an octagon Building projecting beyond it, one is a Summer House & probably the other is a Temple, it is locked up, & at first sight they might be thought to be intended for such purposes but on finding that one has no holes, People are naturally led to believe that the internal structure is similar, since the outsides are perfectly so.”

- Peale, Charles Willson, July 22, 1810, in a letter to his son, Rembrandt Peale, describing farms in Pennsylvania (Miller et al., eds., 1991: 3:49, 51)[14]

“I visited Job Roberts the day before yesterday, his farm is a model of excellence in the Culture. . . . He is growing several hedges which in less than 7 yrs. will be complete fences against all sorts of Cattle. The management of which is a good lesson, which I hope to make usefull to this place. . . .

“I am often pleased with the solemn groves skirting meadows in majestic silence and cool appearance. There is a Spring belonging to Chas Wistar in the most romantic scinery [sic] your imagination can conceive. . . . The spring comes out a large rock into a bason which is covered with another large rock, then passes beneath a rock under your feet, and bursts out again before it joins the creek.”

- Peale, Charles Willson, July 29, 1810, describing the ground plot at Belfield (Miller et al., eds., 1991: 3:53)[14]

- “This ground plot is made by recollection, but I think it near anough [sic] the truth to give you a more precise Idea of the place & the other Sketches which I intend to annex to my letters.” [Fig. 8]

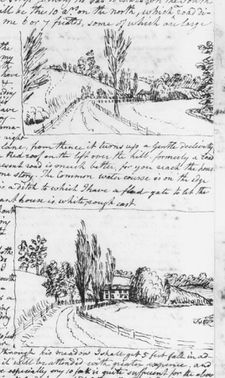

- Peale, Charles Willson, July 29, 1810, describing his sketches of Belfield (Miller et al., eds., 1991: 3:54–56)[14]

“In this view imagine that you see a beautiful Meadow on the right. The Tennants House seems to terminate the lane, from thence it turns up a Gentle declivity to the Mansian, of which you see the Top of a Red roof on the left over the hill. formerly a road went over this hill at the dotted lines. . . . The Common water course is on the edge of the Meadow on the right and the doted [sic] line is a ditch to which I have a flood-gate to let water on the Meadow at Pleasure. . .

“I have marked the ends of some Joice between the windows, from these I intend to make a Piazer extending round the south End. at the X is a fine spring runing out of a Rock—at this I shall make a spring House & perhaps a Mill. . .

“This View is taken at a point [from] the Tennants house a small distance, by which you see the Roof of the Mantion over the Garden fence which are of boards on a Stone Wall. The Barn and one of the Barracks on the West, the Coach-House near the Center, Spring-house on the East side and the Bath House below it. There is 4 large Popplers (Tulip Tree) which crosses the Road, and the Lumbardy Poppler a row of them on your right hand. Just above the bath-House is a small fish pond with about 200 Catfish which I brought from the falls of Schulkill. . .

“In this view the stone steps at the End of the house is seen, which lead to the yard in front of the Garden, the Garden pails are on a stone wall on which grows Creepers now in full bloom they are a fine crimosen [sic] bell flowers in Clusters and an abundance of humming birds are daily sucking the honey. Green Gages, Damsons & quinces are along this wall & beneath rose bushes. you may discover a long Roof which has shelves for Bee hives conveniently situated to get their food from the flowers of the Garden.” [Fig. 9]

- Peale, Charles Willson, August 2, 1813, in a letter to his daughter, Angelica Peale Robinson, describing Belfield (Miller et al., eds., 1991: 3:202)[14]

- “We are now beginning to ornament about the House Our Garden is much admired, Franklin is shewing his taste in neat workmanship. He has built an Elligant Summer House on that commanding spot which you may remember being pointed out to you. It is a hexicon base with 6 well turned Pillars supporting a circular Top & dome on which is placed a bust of Genl. Washington, it would have been more appopriate [sic] to have had 13 pillars, but I did not want so large a building, and it was work enough for Franklin to turn those 6 pillars which he was able to execute will [with] the layth in the mill.”

- Peale, Charles Willson, November 12, 1813, in a letter to his daughter, Angelica Peale Robinson, describing Belfield (Miller et al., eds., 1991: 3:216)[14]

- “I have made an Oblisk to terminate a Walk in the Garden, read in Dictionary of Arts for description of them. I made it of rough boards & white washed it with lime & allum—The allum It is said will convert the lime in time to Stone. I have put the following motto on it—on one side ‘Never return an Injury, It is a noble Triumph to overcome Evil by Good.’ another, ‘Labour while you are able it will give health to the Body—peaceful content to the mind.’ another, ‘He that will live in peace & Rest, must hear, and see, and say the best & in french ‘y voy, & te tas, si tu veux vivre en paix.’ and on another ‘Neglect no Duty.’ The distick which I have adopted is claimed by several Nations, I have put the french because it is more concise & equally expressive.”

- Peale, Charles Willson, November 22, 1815, in a letter to his daughter, Angelica Peale Robinson, describing Belfield (Miller et al., eds., 1991: 3:370–71)[14]

“I have also painted . . . a tolerable large Landscape almost finished, it is a View of the Garden and most of the Buildings, as seen from what we call my seat in the Walk to the mill,—difficult part in it, that is, a representation of the down hill or rather Valley between the point of sight and the Garden.

“The objects in sight are the road ascending to the Dwelling, Stone wall & Thorn hedge on it inclosing the Garden. The Garden Gate at the Fountain, Green House, Summer house a doom supported by 6 Pillars and bust of Washington crowning it – beyond that an Oblisk The Hay barracks; Barn with the wind mill on top of it to <pu> pump water for the Stock; Stables; Mantion-House Wash house and connecting Piaza; Carriage House; Spring House; Bath house and Cover of the Ice-House. The whole comprehending a tolerable handsome View including Trees of various folliages—But what must render this Picture more interesting, will be some Portraits setting on the Bench under a Beach Tree, (as yet a Small Tree) but being the nearest object, it must be most distinctly finished, The declining Meadow will form a charming background for the figures on the Bench. There should also be figures in various parts of the Ground to give animation to the sciene, all of which are yet to be done. I intend it for the Museum when finished to my mind I wish I could have you as one of the figure on the Bench.” [Fig. 10]

- Peale, Charles Willson, March 15, 27, 29, 1814, in a letter to his sons, Benjamin Franklin Peale and Titian Ramsey Peale, describing Belfield (Miller et al., eds., 1991: 3:239)[14]

“As soon as the weather becomes settled & warm, I will have the Bason walled up with a proper morter, and when that is doing I shall put a Cock to the Leaden pipe to let the water pass out untill the Bason is prepaired to receive it. and when my leasure and I can spare a man to hall dirt I will raise the water in the fish Pond which will encrease its surfaces considerably raising the water to the stone wall at the head of the Pond, deeper, and more water, will be better for fish & will raise the get [jet] at the fountain considerably.

“The stone and ground is remooved at the Bottom of the Garden but the Wall is not as high and access into the Garden is not so easey as it used to be, even before any wall is made.”

- Peale, Charles Willson, September 6, 1814, in a letter to his son, Rembrandt Peale, describing Belfield (Miller et al., eds., 1991: 3:263)[14]

- “I have finished my fountain and . . . the Bason holds the water after much labour to make fountain so having raised the Fish-pond it gives a jet of 12 feet high. . . . Rubens has place all his Pots round the fountain B[a]son and it makes a very handsome display, The Bason being 13 feet long & 10 wide.”

- Peale, Charles Willson, September 14, 1814, describing Belfield (Miller et al., eds., 1991: 3:266)[14]

- “The fountain Bason now holds water completly, and the jet is 12 feet high, and is kept continually playing; Day & night, Rubens has placed all his plants round the Bason, and it is very handsome.”

- Peale, Charles Willson, August 4, 1816, in a letter to his son, Rembrandt Peale, describing Belfield (quoted in Rudnytzky 1986: 44)[10]

- “I have been so long neglecting the view I am about in [the] garden that the trees & shrubbery have grown so high that I cannot represent them truly without almost totally hiding the walks, therefore I shall prefer leaving out many of them—and also make them smaller.”

- Peale, Charles Willson, October 13, 1816, describing Belfield (Miller et al., eds., 1991: 3:452)[14]

- “Other parts of my farm excited the curiousity of the Public—a wind-mill for pumping Water for the Cattle &c.—A falling Garden, fountain, fish Pond, common Sewers &c Machines to add [aid] the dairy and carriages of various uses—all these things employed the whole of my time to emprove & to keep them in proper order.”

- Peale, Charles Willson, October 1, 1818, in a letter to his son, Rembrandt Peale (Miller et al., eds., 1991: 3:607)[14]

- “'I have chosen two views I wish to paint, one is at the beginning of the rise of the high hill leading to Germantown, it takes in my Oblisk, Barn and Mansion House and both the Summer Houses—The Gate & willow tree on the left, the hill back of the Garden, the road, the water in the road & mill race, and a piece of Mr. Wistar's wood for a finish on the right of the picture.”

- Peale, Charles Willson, January 14, 1824, in a letter to his son, Charles Linnaeus Peale, describing Belfield (quoted in Rudnytzky 1986: 32)[10]

- “Dear Linnius I wish you to consider whether it is not better to avoid these expenses by burying your Child in the Garden on the south side of the Oblisk, a place which if I hold the farm untill my decease, I shall desire to have my body deposited. This has been my determination ever since I painted those inscriptions.”

- Peale, Charles Willson, c. 1825, describing Philadelphia (Miller et al., eds., 2000: 5:91)[14]

“When Peace was concluded between Great Britain & the united States of America, President Dickenson and the Executive Counsil employed Peale to paint a Triumphal Arch in transparent Colours. It consisted of three arches, the Center Arch was 20 feet high, and the side arches each 15 feet high, and the whole length extended nearly to the width of Market street, and it was 46 feet high, independant of the statues of the 4 cardenal Virtues larger than human figures. The architecture was of the Ionic order, ornamented with reaths of Flowers, in festoons and winding round the Columes. It was also ornamented in sundry parts of the building as follows[:]

“A figure of Peace, represented in a beautiful female figure, and various attendants amidst the Clouds. These were to be lighted by lights placed behind the clouds and out of the sight of the spectators, and doubtless would have had a most pleasing affect in passing down from the Top of the Presidents House to the Triumphal Arch, with a fuse in the hand of Peace, which was to be directed to a fuse which would light 1100 Lamps, & illuminate the whole of the Triumphal Arch in a minute.”

- Peale, Charles Willson, c. 1825, describing Wye House, estate of Col. Edward Lloyd, Talbot County, MD (Miller et al., eds., 2000: 5:147)[14]

- “The Coll. is possessed of immence property, he had 400 Ars. of land in a park to keep Deer, round which was a fence of 20 rails high, Maise were planted within for sustenance of his deer.”

- Peale, Charles Willson, c. 1825, describing the Brideswell (Workhouse), New York, NY (Miller et al., eds., 2000: 5:167–68)[14]

- “In the garden they saw the remains of the statue of Mr. Pitt . . . the head was gone and other parts much mutilated, This was done by the British, pehaps because the americans had broken to pieces the statue of King George, which was an equistrian statue of Lead, which they cast into bullets.”

- Peale, Charles Willson, c. 1825, describing New York, N.Y. (Miller et al., eds., 2000: 5:247–48)[14]

“Peale went to a bathing house on the north river, this building has a private as well as public bathing places, for men or women. The cost of public bathing is 12 1/2 Cts. and 25 Cents for private bathing. . . .

“The public Bath is extended wings on each side about 40 feet into the river on which there are a range of boxes to dress and undress, these have stairs with ropes to decend into the water on the 3 sides and at the end next the river is a sunken vessel of an oblong square, and the debth of the water therein is about 4 feet, for the accomdation of those who cannot swim. In the private baths they have the same kind of vessels which rise and fall with the tide. You are furnished with a towel and an oil cap for the head. They have warm baths for those who want them. The[re] is another bathing house on the same river, which at present is not in order except for the accomodation of women.

“If there were also Bathing houses on the east river, and it was the custom generally for the Inhabitants to make frequent use, especially during the hot seasons, it would contribute much to ward off those dreadful fevers which too oftain afflict large Cities.

“Walking with Mrs. Peale one evening to take the fresh air at the Battery, in those pleasant gravelly walks skirted with Trees. Adjoining to these pleasure grounds they observed places of entertainment brilliantly lighted up with lamps and to regaile the Ear a variety of Musick—they are called Gardens, small but neatly fitted up with boxes and seats, walks divided by small beds of flowers. In the center of that they visited was a circular sort of Temple with an ornamented vase in the center, round the cornich [cornice] of this temple a considerable number of lamps, the light of which shew a number of small jets from the vase of waters thrown as high as the cornish. perhaps this fountain gets its supply of water from some resevoir in the adjacent building, and by pipes beneath the walks conveyed to the Vase. They paid 1/4$ for each ticket, which purchases Ice creams, Cakes or other refreshments as may be choosen to the value. There was another Garden near this where the company are regailled with vocal musick.”

“The proprietor made summer houses (so called) roofs to ward off the Sunbeams with seats of rest. one made of the chinease [sic] taste, dedicated to medieation [sic], with the following sentiments round within it:

“Mediate on the Creation of Worlds, which perform their evolutions in proscribed periods! . . .

“He wanted a place to keep the garden seeds & Tools, and in a part of the Garden where a seat in the shade was often wanted, he built a shed or small room, and to hide that Salt-like-box, and to try his art of Painting, he made the front like [a] Gate Way with a step to form a seat, and above, steps painted as representing a passage through an Arch beyond which was represented a western sky, and to ornament the upper part over the arch, he painted several figures on boards cut to the outlines of said figures as representing statues in sculpture. . . .

“Having a good spring-house the water from it supplied a small fish-pond, in which he put many cat-fish brought from the Schulkill and although they lived and perhaps might be breed there yet being petts never was served at his table[.] The same with Pidgeons, they had commodious house, and once a pr. of squabs was taken to the Kitchen, but the Parent came after them and alighting on the Kitchen window, Mrs. Peale’s delicate feelings could not suffer them to be killed and accordingly they were returned to the Pidgeon-house.

“finding a spring stream in the Garden he followed it up the side of the hill, untill it become of some debth and among large Stones—and having at this place made a considerable cavity in the bank round the source of the Spring, to wall it up this hollow and arch it over, it was thought that it might be an excellent place to keep cabbage and Turnups &c during the winter season, but on tryal it was found to[o] moist and warm, for those vegetables sprouted and took a second groath, and they were obliged to take them out, in the first of January, and cover them with earth in the usial mode. This tryal gave the Idea of building a green house jouining to the arched cave—and that Green house keepted all exotic plants perfectly well without the aid of Stoves in the severest winters.

“below the Green house he made a round bason to receive the Water from the cave back of it—and from the fish-pond near the spring-house, to this bason in the Garden is a fall of 15 feet, and in order to have a fountain in the Bason he put log-pipes under ground, and thus had a jet of 13 feet high but of small diameter, in order that it might constantly [be] rising. but unfortunately he make the bore of his logs only of one inch diameter, the consequence was that Frogs in two instances got into the bore of the logs and not being able to pass through all the joints, stopped the water, of course to free the passage of the logs, gave much labour. had these things been foreseen, trouble might have been prevented, by making the bore of the logs of a greater diameter, with other provisions to keep the passage free.”

Images

James Trenchard after Charles Willson Peale, “An East View of GRAY’S FERRY, near Philadelphia, with the TRIUMPHAL ARCHES, &c. erected for the Reception of General Washington, April 20th. 1789,” in Columbian Magazine 3, no. 5 (May 1789): pl. opp. 282.

Charles Willson Peale, Sketches of Belfield, 1810.

Charles Willson Peale, Letter to Angelica Peale describing his garden at Belfield, Nov. 12, 1813.

Charles Willson Peale, Letter to Angelica Peale describing his garden at Belfield, Nov. 22, 1815.

Charles Willson Peale, Cabbage Patch, The Gardens of Belfield, Pennsylvania, c. 1815–16.

Charles Willson Peale, Belfield Farm, c. 1816.

Charles Willson Peale, View of the garden at Belfield, 1816.

Charles Willson Peale, “Grand Civic Arch,” 1824, in Charles Coleman Sellers, “Charles Willson Peale with Patron and Populace,” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 59, no. 3. (1969): 103.

Other Resources

Library of Congress Authority File

Notes

- ↑ David Ward, Charles Willson Peale: Art and Selfhood in the Early Republic (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 8–16, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Ward 2004, 26–29, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Coleman Sellers, Charles Willson Peale (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1969), 119–20, view on Zotero. Peale would marry three times and have eighteen children, though only eleven of them would live to adulthood. See Kate Nearpass Ogden, “The Peale Family of Painters,” in The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, http://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/peale-family-of-painters/.

- ↑ Ward 2004, 72–73, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Sellers 1969, 99–100, view on Zotero; Ward 2004, 45–46, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Ward 2004, 83, view on Zotero. Ward describes this series as a “pantheon that would perpetuate American republicanism.”

- ↑ Sellers 1969, 214, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Sidney Hart and David C. Ward, “Peale’s Philadelphia Museum,” in Lillian B. Miller and David C. Ward, eds., New Perspectives on Charles Willson Peale (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1991), 222–23, 233, view on Zotero. Though Peale would continue to paint in the coming years, his output was less prodigious; see Sellers 1969, 262, for Peale’s notice of his retirement in Claypoole’s Daily Advertiser (April 24, 1794), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Therese O’Malley, “Belfield in American Garden History,” in Miller and Ward 1991, 271–72, view on Zotero; David C. Ward, “Enlightened Agriculture in the Early Republic,” in Miller and Ward 1991, 291–93, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Kateryna Rudnytzky, “The Union of Landscape and Art: Peale’s Garden at Belfield” (honor’s thesis, La Salle University, 1986), 25, view on Zotero; O’Malley 1991, 269, view on Zotero; Ward 1991, 297, [1].

- ↑ O’Malley 1991, 269–74, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Roger B. Stein’s essay “Charles Willson Peale's Expressive Design: The Artist in His Museum” offers an in-depth analysis of this painting; see Miller and Ward 1991, 167–218, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Sellers 1969, 431–33, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 14.00 14.01 14.02 14.03 14.04 14.05 14.06 14.07 14.08 14.09 14.10 14.11 14.12 14.13 14.14 14.15 14.16 14.17 14.18 Lillian B. Miller et al., eds.,, eds., The Selected Papers of Charles Willson Peale and His Family, 5 vols. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1983–2000), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Coleman Sellers, “Charles Willson Peale with Patron and Populace,” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 59, no. 3. (1969), view on Zotero.