Bridge

History

Bridges had many applications beyond the bounds of the garden. The term bridge referred to structures that carried pedestrians, carriage, and rail traffic over obstacles such as water and ravines. In the context of the garden, however, bridges also took on ornamental roles, and their construction was dictated by aesthetics as well as load-bearing requirements.

Bridges were built by the earliest settlers along main transportation routes. It is not until the second half of the 18th century, a period of sharp increase in the construction of elaborate landscape gardens, that there is evidence of bridges constructed specifically for garden settings. Treatises such as William and John Halfpenny’s Rural Architecture in the Chinese Taste (1755) and J. C. Loudon's An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826) demonstrate a wide variety of designs, styles, and materials used for bridges. Most American examples of garden bridges, however, appear to have followed relatively simple designs built of wood and stone.

Garden bridges were built over waterways both natural, as with the cascade at Blithewood on the Hudson River [Fig. 1], and artificial, as at the Vale in Waltham, Massachusetts [Fig. 2]. At the garden of the Vassall-Craigie-Longfellow House in Cambridge, Massachusetts, it was said that a pond was created “as an apology for the bridge.” While water was the most common obstacle crossed, bridges were used also to span roads or depressions, such as fosses or ditches. Around 1804, Thomas Jefferson proposed a bridge to connect the park grounds of his estate, which lay on either side of a public road.

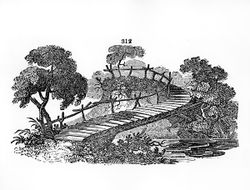

Bridges also were used as focal points and as viewing platforms. At Gray’s Garden in Philadelphia and William Paca’s garden in Annapolis, a bridge was used to signal movement from one part of a garden to another. In Paca’s garden, the bridge has been reconstructed using a combination of archaeological findings and Charles Willson Peale's portrait of Paca [Fig. 3]. Crossing the fish-shaped pond, the bridge marks the transition between the regular geometric form of the parterres and the relative naturalism of the wilderness at the base of the garden.

The artistic convention of using a bridge to demarcate various zones in a landscape painting, a practice that can be traced back to 17th-century painters, explains the prominence of bridges in paintings of estate gardens. This compositional technique is particularly apparent in the work of artists who sought to model themselves after the pastoral painting traditions of Poussin, Claude, and the Carracci. A case in point is Charles B. Lawrence’s painting of the Bordentown, New Jersey, estate Point Breeze [Fig. 4], in which the artist used a bridge to define the middle ground between the Delaware River in the foreground and the distant prospect of the house. In his painting of Canfield House [Fig. 5], in Sharon, Connecticut, Ralph Earl took painterly poetic license by using a bridge to frame his view of the house, echo the line of the road, and lead the viewer to examine the wider landscape.[1] 18th-century treatise writer Thomas Whately, a strong advocate of modeling designed landscapes after paintings, suggested using a ruined bridge in “wild and romantic scenes” as a picturesque object that would lend “antiquity to the passage.” His advice was repeated by later writers such as George William Johnson in A Dictionary of Modern Gardening (1847) who recommended bridges as a means to create the illusion that a pond was a river or lake, visually amplifying the extent of the property.

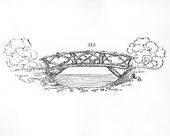

Although American garden bridges were generally simpler than many of the designs included in garden and architectural treatises, a clear change in style occurred through time. In the eighteenth century, bridges such as those described in Gray’s Garden in 1790 displayed the fashion for the exotic allure of China. William and John Halfpenny (1755) and Bernard M’Mahon (1806) articulated the “romantic and pleasing effect” of Chinese-style garden elements. The Halfpennys’ Rural Architecture in the Chinese Taste included numerous designs for bridges, including a plan of a single-trussed timber bridge [Fig. 6] that strikingly resembles the bridge in the Paca portrait. In the 19th century, rustic bridges, such as those described by A. J. Downing (1847), became popular. Builders often used materials that appeared to be natural. For instance, the irregularly shaped branches with their original bark and the rugged stone used at Mr. V.’s residence in Hallowell, Maine, were described by Timothy Dwight (1796) as resulting from an “accident, rather than the effect of human labour.” Such rustic bridges were in keeping with the irregular and naturalistic qualities associated with the picturesque, and were particularly recommended for moving water and smaller streams. Johnson’s passage of 1847 argued for the suitability of a bridge’s scale, design, and materials to its setting. A bridge, he wrote, is “not a mere appendage to a river, but a kind of property which denotes its character.”

—Elizabeth Kryder-Reid

Texts

Usage

- Constantia [Judith Sargent Murray], June 24, 1790, “Description of Gray’s Gardens, Pennsylvania” (Massachusetts Magazine 3: 414)[2]

- “. . . this [avenue], as well as all the smaller avenues, alike produces us in the wilderness, into which we enter, passing over a neat chinese bridge, preparing with much pleasure to penetrate a recess so charming. It is indeed a wilderness of sweets, and the views instantly become romantically enchanting, the scene is every moment changing. Now, side long bends the path; then, pursues its winding way; now, in a straight line; then, in a pleasing labyrinth is lost, until, in every possible direction, it breaketh upon us, amid thick groves of pines, walnuts, chestnuts, mulberries, &c. &c. we seem to ramble, while at the same time, we are surprized [sic] by borders of the richest, and most highly cultivated flowers, in the greatest variety, which even from a royal parterre we might be led to expect.”

- Dwight, Timothy, 1796, describing the residence of Mr. V., Hallowell, ME (1821: 2:219)[3]

- “Behind the garden is a. . . small mill stream. . . On either side, the banks, which are of considerable height, and sometimes steep, formed of rude forested grounds, and moss-grown rocks, are left absolutely in the state of nature. Along the brook Mr. V. has made a convenient foot-way, rather appearing to have been trodden out by the feet of wild animals, than to have been contrived by man, and winding over a succession of stone bridges, so rude and inartificial, as to seem the result of accident, rather than the effect of human labour.”

- Jefferson, Thomas, c. 1804, describing the improvements of Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, VA (Massachusetts Historical Society, Coolidge Collection)

- “The north side of Monticello. . . and all Montalto above the thoroughfare to be converted into park & riding grounds, connected at the thoroughfare by a bridge, open, under which the public road may be made to pass so as not to cut off the communication between the lower & upper park grounds.”

- Ripley, Samuel, 1815, describing the Vale, estate of Theodore Lyman, Waltham, MA (1815: 272)[4]

- “Through the lawn, in front of the mansion house, which is large and handsome, runs Beaver Brook, which it there formed into a serpentine canal, and over which is erected a bridge of three arches, made of the Chelmsford white stone, which is both an ornament to the place, and a specimen of correct taste and workmanship.”

- Bryant, William Cullen, August 25, 1821, in a letter to his wife, Frances F. Bryant, describing the Vale, estate of Theodore Lyman, Waltham, MA (1975: 108)[5]

- “He took me to the seat of Mr. Lyman. . . It is a perfect paradise. . . In front of the house, to the south was an artificial piece of water winding about and widening into a lake, with a little island of pines in it, an elegant bridge crossing it, and swans swimming on the surface.”

- Anonymous, April 28, 1826, “On Landscapes and Picturesque Gardens” (New England Farmer 4: 316)[6]

- “Mr. [Andrew] P[armentier] by the advice of several of his friends, will furnish plans of landscape and picturesque gardens; he will communicate to gentlemen who wish to see him, a collection of his drawings of Cottages, Rustic Bridges, Dutch, Chinese, Turkish, French Pavilions, Temples, Hermitages, Rotundas, &c. For further particulars, inquiries personally, or by letter, addressed to him, post paid, will be attended to.”

- Thacher, James, December 3, 1830, “An Excursion on the Hudson,” describing Hyde Park, seat of Dr. David Hosack, on the Hudson River, NY (New England Farmer 9: 156)[7]

- “This avenue to the mansion is over a stone bridge, crossing a rapid stream precipitated from the milldams above, and falls in a cascade below. The winding of the road, the varied surface of the ground, the bridge, and the falling of the water, continually vary the prospect and render it a never tiring scene.”

- Dearborn, H. A. S., 1832, describing Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, MA (quoted in Harris 1832: 80)[8]

- “In the centre [of the upper garden pond] an island has been formed, having a path on the margin, which is connected with the avenue on the western side by a bridge twenty-four feet in length, neatly railed and painted; and another bridge of like form and extent thrown over the outlet, which affords a communication with the Cemetery ground by the way of the Indian Ridge Path.” [Fig. 7]

- Ritchie, Anna Cora Ogden Mowatt, 1839, describing Point Breeze, estate of Joseph Bonaparte (Count de Survilliers), Bordentown, NJ (quoted in Weber 1854: 186)[9]

- “A narrow stream winds itself gracefully through one part of the grounds, over which several rustic bridges are erected.” [See Fig. 4]

- Trego, Charles, 1843, describing Bedford, PA (1843: 185–86)[10]

- “Near this town are the celebrated Bedford Springs, the water of which has been found to have a beneficial effect in many complaints. . . The buildings for the accommodation of strangers are large and commodious; the grounds about the springs are tastefully ornamented with neat bridges, railings and gravel walks; and few places of the kind present more agreeable attractions to the invalid, the citizen, or the traveller.”

- Longfellow, Alexander W., January 1844, describing the Vassall-Craigie-Longfellow House, Cambridge, MA (quoted in Evans 1993: 38)[11]

- “We were very busy planning the grounds & I laid out a linden avenue for the Professor’s private walk. I was often reminded of your fancy for such things. . . The house is to be repaired but not essentially altered, the old out buildings to be removed, trees planted a pond, & rustic bridge, created the pond is an apology for the bridge.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, October 1847, describing Montgomery Place, country home of Mrs. Edward (Louise) Livingston, Dutchess County, NY (quoted in Haley 1988: 49)[12]

- “He takes another path, passes by an airy looking rustic bridge, and plunging for a moment into the thicket, emerges again in full view of the first cataract.”

- Notman, John, 1848, describing his designs for the Hollywood Cemetery, Richmond, VA (quoted in Greiff 1979: 143)[13]

- “Five bridges are necessary on the whole route. These may be readily and simply constructed of the trunks of the white oaks that have been cut down, laid on abutments of dry stone walling on each side of the runs or brooks, built without mortar; the granite on the ground might be easily quarried to serve the purpose; a simple rustic railing made of the branches of the trees cut down (with the bark on) placed on each side, will be in better keeping with the place and purpose than the most expensive railing planed and painted.”

Citations

- Halfpenny, William and John, 1755, Rural Architecture in the Chinese Taste (1755: 7)[14]

- “Represents the Plan of a single truss’d Timber Bridge, whose Span is 30 Feet and Width in the Clear 9 Feet. The Posts tend to the Center of the Curve, and the Floor of the Bridge, with the Rails, &c. answerable thereto; for the Length and Scantling of the Timbers see the Scale. This Bridge contains 380 Cube Feet of Timber.” [Fig. 8]

- Anonymous, 1798, Encyclopaedia (1798: 7:561)[15]

- “‘IV. The BRIDGE should never be seen where it is not wanted: a useless bridge is a deception; deceptions are frauds; and fraud is always hateful, unless when practised to avert some greater evil. A bridge without water is an absurdity; and half an one stuck up as an eye-trap is a paltry trick, which, though it may strike the stranger, cannot fail of disgusting when the fraud is found out. . .

- “In the construction of bridges also, regard must be had to ornament and utility. A bridge is an artificial production, and as such it ought to appear. It ranks among the noblest of human inventions; the ship and the fortress alone excel it. Simplicity and firmness are the leading principles in its construction.’ Practical Treatise on Planting and Gardening p. 593 &c.”

- Repton, Humphry, 1803, Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1803: 6)[16]

- “The same reasoning induced me to prefer at STOKE POGIES a bridge of more arches than one over a river which is the work of art, whilst in natural rivers a single arch is often preferable, because in the latter we wish to increase the magnitude of the bridge, whilst in the former we endeavour to give importance to the artificial river.”

- M’Mahon, Bernard, 1806, The American Gardener’s Calendar (1806: 61, 65)[17]

- “. . . if it [water] should be continued to any considerable length, one or more ornamental Chinese bridges, may be carried over it at convenient places, which will have a beautiful effect, and serve for communication with the opposite divisions, on each side of the rivulet. . .

- “Ornamental bridges over artificial rivers, or any rural piece of water in some magnificent opening, so as to admit of a prospect thereof, at some distance from the habitation, have charming effects. . .

- “It being absolutely necessary to have the whole of the pleasure ground surrounded with a good fence of some kind, as a defence against cattle, &c. a foss being a kind of concealed fence, will answer that purpose where it can conveniently be made, without interrupting the view of such neighbouring parts as are beautified by art or nature, and at the same time affect an appearance that these are only a continuation of the pleasure-ground. Over the foss in various parts may be made Chinese and other curious and fanciful bridges, which will have a romantic and pleasing effect.”

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826: 348, 350–51)[18]

- “1769. Useful decorations are such as while they serve as ornaments, or to heighten the effect of a scene, are also applied to some real use, as in the case of cottages and bridges. They are the class of decorative buildings most general and least liable to objection. . .

- “1782. The bridge is one of the grandest decorations of garden-scenery, where really useful. None require so little architectural elaboration, because every mind recognises the object in view, and most minds are pleased with the means employed to attain that object in proportion to their simplicity. There are an immense variety of bridges, which may be classed according to the mechanical principles of their structure; the style of architecture, or the materials used. . .

- “1783. The fallen tree is the original form, and may sometimes be admitted in garden-scenery, with such additions as will render it safe, and somewhat commodious.

- “1784. The foot-plank is the next form, and may or may not be supported in the middle, or at different distances by posts.

- “1785. The Swiss bridge . . . is a rude composition of trees unbarked, and not hewn or polished. . . [Figs. 9 and 10]

- “1787. A very light and strong bridge may be formed by screwing together thin boards in the form of a segment, or by screwing together a system of triangles of timber. . .

- “1788. Bridges of common carpentry. . . admit of every variety of form, and either of rustic workmanship or with unpolished materials, or of polished timber alone, or of dressed timber and abutments of masonry.

- “1789. Bridges of masonry. . . may either have raised or flat roads; but in all cases those are the most beautiful (because most consistent with utility) in which the road on the arch rises as little above the level of the road on the shores as possible . . .

- “1790. Cast-iron bridges are necessarily curved; but that curvature, and the lines which enter into the architecture of their rails, may be varied according to taste or local indications.”

- Anonymous, April 28, 1826, “On Landscapes and Picturesque Gardens” (New England Farmer 4: 316)[19]

- “A few fabrics, rustic bridges, hermitages, a Temple, or a Chinese Kiosk or Pagoda, not expensive in their execution, would advantageously complete the embellishment of a country seat.”

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828: 1:n.p.)[20]

- “BRIDGE, n. [Sax. bric, brieg, brigg, or brye, bryeg; Dan. broe; Sw. bryggia, bro; D. brug; Ger. brücke; Prus. brigge.]

- “1. Any structure of wood, stone, brick, or iron, raised over a river, pond, or lake, for the passage of men and other animals. Among rude nations, bridges are sometimes formed of other materials; and sometimes they are formed of boats, or logs of wood lying on the water, fastened together, covered with planks, and called floating bridges. A bridge over a marsh is made of logs or other materials laid upon the surface of the earth. . . Encyc.”

- Anonymous, April 1, 1837, “Landscape Gardening” (Horticultural Register 3: 129)[21]

- “Foot bridges are always pleasing where there are streams.”

- Sayers, Edward, November 1, 1837, “On Laying out Gardens and Ornamental Plantations” (Horticultural Register 3: 410)[22]

- “A well-contrived bridge over a stream of water gives the same impression of improvement by a better communication from one part of the ground to the other.”

- Johnson, George William, 1847, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening (1847: 99)[23]

- “BRIDGES are inconsistent with the nature of a lake, but characteristic of a river; they are on that account used in landscape gardening to disguise a termination; but the deception has been so often practised, that it no longer deceives, and a bolder aim at the same effect will now be more successful. If the end can be turned just out of sight, a bridge at some distance raises a belief, while the water beyond it removes every doubt, of the continuation of the river; the supposition immediately occurs, that if a disguise had been intended, the bridge would have been placed further back, and the disregard thus shown to one deception gains credit for the other.

- “As a bridge is not a mere appendage to a river, but a kind of property which denotes its character, the connexion between them must be attended to; from the want of it, the single wooden arch once much in fashion, seemed generally misplaced; elevated without occasion so much above it, it was totally detached from the river; and often seen straddling in the air, without a glimpse of the water to account for it, and the ostentation of it as an ornamental object diverted all that train of ideas which its use as a communication might suggest. The vastness of Walton Bridge cannot without affectation be mimicked in a garden where the magnificent idea of inducting the Thames under one arch is wanting; and where the structure itself, reduced to a narrow scale, retains no pretension to greatness. Unless the situation make such a height necessary, or the point of view be greatly above it, or wood or rising ground instead of sky behind it fill up the vacancy of the arch, it seems an effort without a cause, forced and preposterous.

- “The vulgar footbridge of planks, only guarded on one hand by a common rail, and supported by a few ordinary piles, is often more proper. It is perfect as a communication, because it pretends to nothing further, it is the utmost simplicity of cultivated nature; and if the banks from which it starts be of a moderate height, its elevation preserves it from meanness.

- “No other species so effectually characterizes a river; it seems too plain for an ornament, too obscure for a disguise; it must be for use, it can be a passage only; it is therefore spoiled if adorned, it is disfigured if only painted of any other than a dusky colour. But being thus incapable of all decoration and importance, it is often too humble for a great, and too simple for an elegant scene. A stone bridge is generally more suitable to either, but in that also an extraordinary elevation compensates for the distance at which it leaves the water below.

- “A gentle rise and easy sweep more closely preserve the relation; a certain degree of union should also be formed between the banks and the bridge, that it may seem to rise out of the banks, not barely to be imposed upon them; it ought not generally to swell much above their level, the parapet wall should be brought down near to the ground, or end against some swell, and the size and the uniformity of the abutments should be broken by hillocks or thickets about them; every expedient should be used to mark the connexion of the building, both with the ground from which it starts, and the water which it crosses.

- “In wild and romantic scenes may be introduced a ruined stone bridge, of which some arches may be still standing, and the loss of those which are fallen may be supplied by a few planks, with a rail thrown over the vacancy. It is a picturesque object, it suits the situation and the antiquity of the passage; the care taken to keep it still open, though the original building is decayed, the apparent necessity which thence results for a communication, give it an imposing air of reality.— Whateley.”

- Elder, Walter, 1849, The Cottage Garden of America (1849: 26)[24]

- “The rich gentleman may have his broad domain finely diversified with wood lots, open fields, deep ravines, creeks, cataracts, canals, rock works, fancy or rustic bridges, etc.; and the wide extended lawn, with its dark green sod, which surrounds his mansion, may be beautifully interspersed with winding walks and deciduous and evergreen trees.”

Images

Inscribed

William and John Halfpenny, “A Single Truss’d Bridge in the Chinese Taste,” in Rural Architecture in the Chinese Taste (1755), pl. 27.

William and John Halfpenny, “A Single Truss’d Bridge in the Chinese Taste,” in Rural Architecture in the Chinese Taste (1755), pl. 25.

Charles Varlé, Project for the Improvement of the Square and the Town of Bath [detail], 1809.

Jacques-Gerard Milbert (artist), Formentin (printer of plates), State of New-York. Mc.Comb’s Bridge Avenue, c. 1819.

J. C. Loudon, “The Swiss bridge,” in An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826), p. 350, fig. 312.

J. C. Loudon, "The Swiss bridge,” in An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826), p. 351, fig. 313.

Robert Mills, “Plan of the Mall,” 1841.

Anonymous, “A rustic bridge,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849), p. 461, fig. 89.

A. J. Downing, Suspension bridge across the Canal [proposed], 1851.

Associated

Charles B. Lawrence, Point Breeze, c. 1820.

Anonymous, “Garden Pond,” in The Picturesque Pocket Companion, and Visitor’s Guide, through Mount Auburn (1839), p. 85.

Attributed

Charles Willson Peale, William Paca, 1772.

James Trenchard after Charles Willson Peale, “An East View of Gray's Ferry, on the River Schuylkill,” in Columbian Magazine 1 (August 1787): pl. opp. p. 565.

Ralph Earl, Landscape View of the Canfield House, c. 1796.

Pavel Petrovich Svinin, The Upper Bridge over the Schuylkill, Philadelphia—Lemon Hill in the Background, c. 1811–13.

Janika de Fériet, The Hermitage, c. 1820.

Joseph Jacques Ramée (artist), J. Klein and V. Balch (engravers), “View of Union College in the City of Schenectady,” c. 1820.

Alexander Jackson Davis, View in Grounds at Blithewood, Seat of Robt. Donaldson, 1840.

Alexander Jackson Davis, View in Grounds at Blithewood, Seat of Robt. Donaldson, Dutchess Co. Hud.[son] riv[er]. N.Y., 1840.

Anonymous, House Lot, Gardens, and Orchard of Bacon’s Castle (after an 1843 survey plan), 1911, in Peter Martin, The Pleasure Gardens of Virginia: From Jamestown to Jefferson (1991), p. 10. fig. 5.

Notes

- ↑ Elizabeth Mankin Kornhauser, Ralph Earl: The Face of the Young Republic (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1991), 208, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Constantia [Judith Sargent Murray], “Description of Gray’s Gardens, Pennsylvania,” Massachusetts Magazine, or, Monthly Museum of Knowledge and Rational Entertainment 7, no. 3 (July 1791): 413–17, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Timothy Dwight, Travels; in New England and New York, 4 vols. (New Haven, CT: T. Dwight, 1821), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel Ripley, “A Topographical and Historical Description of Waltham, in the County of Middlesex, Jan. 1, 1815,” Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society 3 (January 1815): 261–84, view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Cullen Bryant, The Letters of William Cullen Bryant, ed. William Cullen II Bryant and Thomas G. Voss (New York: Fordham University Press, 1975), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, “On Landscape and Picturesque Gardens,” New England Farmer 4, no. 40 (April 28, 1826): 316, view on Zotero.

- ↑ James Thacher, “An Excursion on the Hudson. Letter II,” New England Farmer, and Horticultural Journal 9, no. 20 (December 3, 1830): 156–57, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thaddeus William Harris, A Discourse Delivered before the Massachusetts Horticultural Society on the Celebration of Its Fourth Anniversary, October 3, 1832 (Cambridge, MA: E. W. Metcalf, 1832), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Constance Weber, “A Sketch of Joseph Bonaparte,” in Godey’s Lady’s Book (Philadelphia: L. A. Godey, 1854), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles B. Trego, A Geography of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia: Edward C. Biddle, 1843), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Catherine Evans, Cultural Landscape Report for Longfellow National Historic Site, History and Existing Conditions (Boston: National Park Service, North Atlantic Region, 1993), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jacquetta M. Haley, ed., Pleasure Grounds: Andrew Jackson Downing and Montgomery Place (Tarrytown, NY: Sleepy Hollow Press, 1988), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Constance Greiff, John Notman, Architect, 1810–1865 (Philadelphia: Athenaeum of Philadelphia, 1979), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Halfpenny and John Halfpenny, Rural Architecture in the Chinese Taste (Bronx, NY, and London: Benjamin Blom, 1968), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, Encyclopaedia, or A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Miscellaneous Literature, 18 vols. (Philadelphia: Thomas Dobson, 1798), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Humphry Repton, Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (London: Printed by T. Bensley for J. Taylor, 1803), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bernard M'Mahon, The American Gardener’s Calendar: Adapted to the Climates and Seasons of the United States. Containing a Complete Account of All the Work Necessary to Be Done . . . for Every Month of the Year . . . (Philadelphia: Printed by B. Graves for the author, 1806), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, 4th ed. (London: Longman et al., 1826), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, “On Landscape and Picturesque Gardens,” New England Farmer 4, no. 40 (April 28, 1826): 316, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, “Landscape Gardening,” Horticultural Register, and Gardener’s Magazine 3 (April 1, 1837): 121–31, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Edward Sayers, “On Laying out Gardens and Ornamental Plantations,” Horticultural Register, and Gardener’s Magazine 3 (November 1, 1837): 409–11, view on Zotero.

- ↑ George William Johnson, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening, ed. David Landreth (Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1847), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Walter Elder, The Cottage Garden of America (Philadelphia: Moss, 1849), view on Zotero.