Alley

(Allée, Allies, Ally)

See also: Arcade, Avenue, Walk

History

Alley is used in the American setting to describe various forms of walks bordered by plantings on either side, and often appears alongside avenue and walk in treatises and descriptions (see Avenue and Walk).[1] General dictionaries, such as those by Thomas Sheridan and Noah Webster, even define walks and alleys to be synonymous. Despite their similar meanings, however, the term “walk” was more broadly defined in specialist literature; walks occur in a variety of settings outside the garden (for example, rope walks). Alley, despite its frequent use denoting a narrow passage in a town, has a more particular association with the designed landscape than either avenue or walk, having been derived from the French verb aller (to go), which was often associated in British and American gardening treatises with French formal gardens.

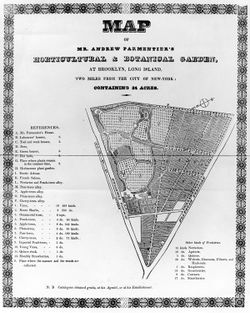

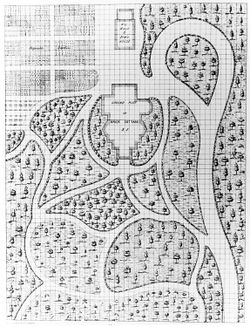

The repeated use of the phrase “walks and alleys” in American garden writing suggests that there was a distinction between the two terms, although that nuance of meaning is neither clear nor consistent. In the late 17th century, French treatise author Jean de La Quintinie often used the terms “alley” and “walk” interchangeably, and distinguished alleys as more narrow than avenues (view text). Other treatise writers find the main criteria of an alley to be a walkway formed between two rows of plantings, defined by either low borders, such as in Lewis Beebe’s description of flowers lining alleys in a Mr. Pratt’s garden (view text), or by tall, mature shade trees forming an enclosing canopy. This latter definition was exemplified at New Haven Burying Ground (as described by Timothy Dwight in 1796) (view text), André Parmentier’s Horticultural and Botanical Garden [Fig. 1], with its alleys of nectarine, peach, pear, apple, plum, and cherry trees, and Thomas Jefferson’s plantation, Monticello [Fig. 2]. In contrast to the treatises, usage examples suggest that alley referred to walkways of all sizes planted on either side, from the pedestrian paths of Gray’s Garden in Philadelphia and Jefferson’s six-foot-wide “allies” between grass plots at Monticello to the alley wide enough for two carriages to pass at the New Haven Burying Ground. The “Tenpin Alley” in the pleasure grounds of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane [Fig. 3] is an example of the use of the term to describe a site for bowling that looks completely different from the more common garden element, the bowling green.

Alleys also varied in their configuration. Like walks, they included straight, curved, and zig-zagged designs. An avenue was often planted on either side and was generally straight. An alley, on the other hand, was associated both with the geometric regularity of the ancient style and, as in André Parmentier’s usage, with descriptions of winding or serpentine walks in a “modern,” more naturalistic garden (compare with Ancient style). It is in this latter context that Manasseh Cutler’s description of the State House Yard, Philadelphia, cites Hogarth’s “Line of Beauty,” an allusion to mid-18th-century aesthetic theory (view text) (see Landscape gardening and Picturesque).

In any configuration, alleys functioned much like their counterparts, avenues and walks, in directing views in the landscape and in controlling circulation patterns. Like avenues, straight alleys were used to create an impressive approach to the main house’s front entrance and to direct a viewer’s gaze toward a focal point or vista. As G. Gregory (1816) advised (view text), the illusion of depth could be further enhanced by making the alley wider at the entrance than at the termination. Like serpentine walks, a curvilinear alley led garden visitors gradually through the landscape, with each turn revealing a new view or perspective, as conveyed by Manasseh Cutler’s 1787 description (view text) of Gray’s Tavern in Philadelphia.

Treatises describe alleys as usually laid with grass or gravel. The surfaces of American alleys are most commonly described and depicted as gravel, or rolled dirt, although an 1867 description of the garden of Charles Norris in Philadelphia mentions “graveled and grass walks and alleys” (view text). In many parts of America, the climate was less suited to growing turf than in England, and the surface material was likely selected for its durability, drainage, ease of maintenance, availability, and cost, as well as aesthetic concerns. Archaeological examples suggest packed dirt (as at Arthur Allen’s Virginia home, Bacon’s Castle), shell, and gravel were used, although none of the walkways at these sites has been associated with the term “alley.” Based on extensive excavations at Williamsburg, Virginia, the quintessential image of the colonial revival garden, the brick walk, does not appear to have been used there.

—Elizabeth Kryder-Reid

Texts

Usage

- Anonymous, May 22, 1749, describing Charleston, SC (South Carolina Gazette)

- “ . . . a garden, genteelly laid out in walks and alleys, with flower-knots, &c. laid round with bricks.”

- Cutler, Manasseh, July 13, 1787, describing State House Yard, Philadelphia, PA (1888: 1:263)[2]

- “The numerous walks are well graveled and rolled hard; they are all in a serpentine direction, which heightens the beauty, and affords constant variety. That painful sameness, commonly to be met with in garden-alleys, and others works of this kind, is happily avoided here, for there are no two parts of the Mall that are alike. Hogarth’s ‘Line of Beauty’ is here completely verified.” back up to History

- Cutler, Manasseh, July 14, 1787, describing Gray’s Tavern, Philadelphia, PA (1888: 1:275)[2]

- “We then rambled over the Gardens, which are large—seemed to be in a number of detached areas, all different in size and form. The alleys were none of them straight, nor were there any two alike. At every end, side, and corner, there were summer-houses, arbors covered with vines or flowers, or shady bowers encircled with trees and flowering shrubs, each of which was formed in a different taste.” back up to History

- Brissot de Warville, J. P., 1788, describing the State House Yard, Philadelphia, PA (1792: 316)[3]

- “Behind the State-house is a public garden; it is the only one that exists in Philadelphia. It is not large; but it is agreeable, and one may breathe in it. It is composed of a number of verdant squares, intersected by alleys.”

- Dwight, Timothy, 1796, describing New Haven Burying Ground, New Haven, CT (1821: 1:191–92)[4]

- “The field was then divided into parallelograms, handsomely railed, and separated by alleys of sufficient breadth to permit carriages to pass each other. The whole field. . . was distributed into family burying places. . . Each family burying-ground is thirty-two feet in length, and eighteen in breadth: and against each an opening is made to admit a funeral procession. At the divisions between the lots trees are set out in the alleys: and the name of each proprietor is marked on the railing.” back up to History

- Beebe, Lewis, 1800, describing a Mr. Pratt’s garden (exact location undetermined) (Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Journal of Lewis Beebe, 1799–1801, vol. 3)[5]

- “Mr. Pratts garden for beauty and elegance exceeds all that I ever saw—The main alley, 13 feet wide, and 20 rods long is upon each side graced with flowers of every kind and colours—and 18 wide. An alley of 13 feet wide runs the length of the garden thro’ the centre—Two others of 10 feet wide equally distant run parallel with the main alley. These are intersected at right angles by 4 other alleys of 8 feet wide—Another alley of 5 feet wide goes around the whole garden, leaving a border around it of 3 feet wide. . . next to the pales. . . The border of the main alley is ornamented with flowers of every description.” back up to History

- Jefferson, Thomas, c. 1804, describing Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, VA (“Plan of Spring Roundabout at Monticello,” Huntington Library)

- “The allies are 6. f. wide that thro’ the lucerne makes that plot so much more than two acres.” [Fig. 4]

- Graydon, Alexander, 1811, describing the garden of Israel Pemberton, Philadelphia, PA (1811: 34–35)[6]

- “ . . . laid out in the old fashioned style of uniformity, with walks and allies nodding to their brothers, and decorated with a number of evergreens, carefully clipped into pyramidal and conical forms.” [Fig. 5]

- Silliman, Benjamin, 1824, describing Albany, NY (1824: 59)[7]

- “It is perfectly compact—closely built, and as far as it extends, has the appearance of a great city. It has numerous streets, lanes, and alleys, and in all of them, there is the same closeness of building, and the same city-like appearance.”

- Willis, Nathaniel Parker, 1840, quoting an early visitor’s description of Mount Vernon, plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (1840; repr., 1971: 263)[8]

- “At the extremity of these extensive alleys and pleasure-grounds, ornamented with fruit-trees and shrubbery, and clothed in perennial verdure, stands two hot-houses, and as many green-houses, situated in the sunniest part of the garden, and shielded from the northern winds by a long range of wooden buildings for the accommodation of servants.”

- Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), September 1851, describing Rose Hill, residence of George Leland, Waltham, MA, in “Notes on Gardens and Nurseries” (Magazine of Horticulture 17: 411)[9]

- “A main walk extends around the garden, with alleys leading from one side to the other.”

- Logan, Deborah Norris, 1867, describing the garden of Charles Norris, Philadelphia, PA (1867: 6)[10]

- “It was laid out in square parterres and beds, regularly intersected by graveled and grass walks and alleys.” back up to History

Citations

- Parkinson, John, 1629, Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris (1629; repr., 1975: 5)[11]

- “ . . . for the fairer and larger your allies and walkes be, the more grace your Garden shall have, the lesse harme the herbes and flowers shall receive, by passing by them that grow next unto the allies sides, and the better shall your Weeders cleanse both the beds and allies.”

- La Quintinie, Jean de, 1693, “Dictionary,” The Compleat Gard’ner (1693; repr., 1982: n.p.)[12]

- “Allies, are such as we call Walks in any Garden. See Walks, and their Use and Proportion, see in the Body of the Book.

- “Allies, are said to be Bien Tirrées, Bien Repassées, or Bien Retirrées, that is, well plain’d, when they are laid smooth and firm and tight again, with the beater or rouling Stone after they have been scraped or turned up with an Instrument to destroy the Weeds.

- “Diagonal Allies. See Diagonal. [Diagonal Allies, or Lines, are Allies or Lines drawn cross one another through the Center of each, and cross any square in a Garden from corner to corner, thereby to give them the fuller view of the square.]

- Parallel Allies. See Parallel. [Parallel Allies, are Allies of an equal breadth through their whole length, and running along in lines equally distant all along from the lines that compose the sides of the Allies which answer them]. . .

- “Avenues, are certain Allies or Walks in Gardens larger than ordinary, but more properly leading to the front of Houses.” back up to History

- Dezallier d’Argenville, Antoine-Joseph, 1712, The Theory and Practice of Gardening (1712; repr., 1969: 40–41)[13]

- “OPEN Walks may be distinguished into two Kinds; namely, the Alley of Parterres, Bowling greens, Kitchen-gardens, &c. which are formed only by the Yews and Dwarfs of the Borders; and the Walks, which tho’ planted with high Palisades and tall Trees, are however kept open at Top, either by clipping the Palisades to a certain Height, or by trimming the Trees on both Sides, so that you may breathe the pure Air. . .

- “SINGLE Walks are those that consist but of two Rows of Trees or Palisades, to distinguish them from double Walks that have four, which form three Alleys close together, a large one in the Middle, and two on the Sides that accompany it, and are called Counter-walks.”

- Bradley, Richard, 1719–20, New Improvements of Planting and Gardening (1720: 2:141)[14]

- “But plant Asparagus. . . measure out your Ground, allowing four Foot for the Breadth of each Bed, and two Foot for every Alley between the Beds.”

- Chambers, Ephraim, 1741–43, Cyclopaedia (1741: 1:n.p.)[15]

- [vol. 1] “ALLEY, * in gardening, a strait parallel walk, bordered or bounded on each hand with trees, shrubs, or the like. See GARDEN, WALK, EDGING, &tc.

- “*The word alley is derived from the French word aller, to go; the ordinary use of an alley being for a walk, passage, or thorowfare from one place to another.

- “Alleys are usually laid either with grass or gravel. See GRASS, and GRAVEL-Walk.

- “An Alley is distinguished from a path, in this; that in an alley there must always be room enough for two persons at least to walk abreast; so that it must be never less than five feet in breadth; and there are some who hold that it ought never to have more than fifteen.

- “Counter-ALLEYS, are the little alleys by the sides of the great ones.

- “Front-ALLEY, is that which runs strait in the face of a building.

- “Transverse ALLEY, that which cuts the former at right angles.

- “Diagonal ALLEY, that which cuts a square, thicket, parterre, &c. from angle to angle.

- “Sloping ALLEY, is that which either by reason of the slowness of the point of sight, or of the ground, is neither parallel to the front, nor to the transverse alleys.

- “ALLEYS in Ziczac, is that which has too great a descent, and which, on that account, is liable to be damaged by floods; to prevent the ill effects whereof, it has platbands of turf run across it from space to space, which help to keep up the gravel. This last name is likewise given to an alley in a labyrinth, or wilderness, formed by several returns of angles, in order to render it the more solitary and obscure, and to hide its exit.

- “ALLEY in Perspective, is that which is larger at the entrance than at the exit; to give it a great appearance of length.

- “ALLEY of Compartiment, is that which separates the squares of a parterre. . .

- [vol. 2] “QUINCUNX is chiefly used in gardening, for a plantation of trees, disposed originally in a square; consisting of five trees, one at each corner, and a fifth in the middle; which disposition repeated again and again, forms a regular grove, wood, or wilderness, and then viewed by an angle of the square, or parallelogram, presents equal and parallel alleys. . .

- “WALKS, in gardening, See the article ALLEYS.”

- Johnson, Samuel, 1755, A Dictionary of the English Language (1755: 1:n.p.)[16]

- “ALLEY. n.s. [allée, Fr.]

- “1. A walk in a garden. . .

- “2. A passage in towns narrower than a street.”

- Hale, Thomas, 1758–59, A Compleat Body of Husbandry (1758: 1:276)[17]

- “There is great advantage in planting the young trees in rows distant from one another, the husbandman may make use of the ground between for any other growth, till the trees are of some height; and this tilling between, far from hurting the young trees, will assist their growth: and the coppice will grow afterwards with a beautiful regularity, being all laid out into natural walks and alleys.”

- Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufacturers and Commerce, 1769, The Complete Farmer (1769: n.p.)[18]

- “ALLEY, in gardening, implies a strait walk, bounded on both sides with trees or shrubs, and commonly covered with gravel or grass.

- “An ally is distinguished from a path, by being broad enough for two persons to walk a-breast, whereas a path is supposed to admit of only one at a time; but if an alley be wider then ten or twelve feet, it may, with more propriety, be called a walk.

- “Covered ALLEY, is that where the trees on each side meet at the top, so as to form a shade.”

- Abercrombie, John, 1789, The Hot-House Gardener (1789: 24)[19]

- “In the middle bottom space within is formed the pit in which to have the bark-bed, five or six to seven or eight feet wide, in proportion to the width of the house . . . having a narrow walk or alley continued all round between the wall of the pits and that of the flues, and the bottom both of the pit and walk paved with brick or paving tiles."

- Sheridan, Thomas, 1789, A Complete Dictionary of the English Language (1789: n.p.)[20]

- “ALLEY, al'-ly. s. A walk in a garden; a passage in towns narrower than a street.”

- Gregory, G. (George), 1816, A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (1816: 1:n.p.)[21]

- “ALLEY, in perspective, that which, in order to have a greater appearance of length, is made wider at the entrance than at the termination.”

- Parmentier, André, 1828, “The Art of Landscape Gardening” (1828: 185)[22]

- “For where can we find an individual, sensible to the beauties and charms of nature, who would prefer a symmetric garden to one in modern taste; who would not prefer to walk in a plantation irregular and picturesque, rather than in those straight and monotonous alleys, bordered with mournful box, the resort of noxious insects?

- “Where is the person, gifted with any taste, who would not choose those alleys that wind without constraint, in preference to those dull straight lines which can be measured by one glance of the eye, and the monotony of which is unvaried? Instead of this, the modern style presents to you a constant change of scene, perfectly in accordance with the desires of a man who loves, as he continues his walk, to have new objects laid open to his view.”

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828: 1:n.p.)[23]

- “AL'LEY, n. al'ly [Fr. allée, a passage, from aller to go; Ir. alladh. Literally, a passing or going.]

- “1. A walk in a garden; a narrow passage.

- “2. A narrow passage or way in a city, as distinct from a public street.

- “3. A place in London where stocks are bought and sold. Ash.”

- Teschemacher, James E., November 1, 1835, “On Horticultural Architecture” (Horticultural Register 1: 410)[24]

- “But instead of planting these trees in formal close orchard lines, we should dot them about apparently irregularly, but in reality with some plan, at sufficient distances to permit, when full grown, intervals of parterres of flowers; and under each tree we should spread a circular carpet of verdant grass, kept well mown, on which the ripe and bursting peach might fall uninjured, and the disfiguring tread of the gatherer be unseen. The connexion of these circular grass plots by means of trellises of the vine, or variously formed beds of herbaceous and annual flowers, with here and there a screen of three or four thick shrubs, to conceal and protect from early blasts, a bijou or jewel of a recess set apart for small masses of choice flowers, which may suddenly and unexpectedly burst on the wanderer through the alleys—these and a variety of other schemes will afford exercise to the man of taste, and create interest in the visitor.”

- Buist, Robert, 1841, The American Flower Garden Directory (1841: 13)[25]

- “All the large divisions [of a flower garden] should be intersected by small alleys, or paths, about one and a half or two feet wide.”

- Johnson, George William, 1847, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening (1847: 6)[26]

- “ALLEYS are of two kinds. 1. The narrow walks which divide the compartments of the kitchen garden; and 2. Narrow walks in shrubberies and pleasure-grounds, closely bounded and overshadowed by the shrubs and trees.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1849, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849: 63, 89–90)[27]

- “Where a taste for imitating an old and quaint style of residence exists, the symmetrical and knotted garden would be a proper accompaniment; and pleached alleys, and sheared trees, would be admired, like old armor or furniture, as curious specimens of antique taste and custom. . .

- “In these gardens, nature was tamed and subdued. . . The stately etiquette and courtly precision of the manners of our English ancestors, extended into their gardens, and were reflected back by the very trees which lined their avenues, and the shrubs which surrounded their houses. . . the gay ladies and gallants of Charles II’s court. . . fluttering in glittering processions, or flirting in green alleys and bowers of topiary work.”

- Ranlett, William H., 1847–49, The Architect (1847: 1:9, 65)[28]

- “[Design I] PLATE 2.—A protracted ground-plot, showing the several distances and dimensions, in sections of one square yard each. This plot, by its admeasurement of the ground, will guide to a ready location of the dwelling and out buildings, and a tasty arrangement of the trees, shrubbery, walks and alleys of the garden. . . . [Fig. 6]

- “PLATE 48.—A plot of village property 724 feet by 488. It is divided into 16 lots, with the cottages placed 30 ft. from the street. . . The lots are suitably intersected with walks and alleys, and shaded and ornamented by fruit and forest trees and shrubs; with the vegetable gardens near the stables.” [Fig. 7]

Images

Inscribed

Thomas Jefferson, Plan of an orchard at Monticello, c. 1778. “Bailey’s alley” inscribed at the left center.

Thomas Jefferson, “Plan of Spring Roundabout at Monticello,” c. 1804. Jefferson used narrow “allies” to define grass plots.

Anonymous, Map of Mr. Andrew Parmentier’s Horticultural & Botanical Garden, at Brooklyn, Long Island, Two Miles From the City of New York, c. 1828. On the right of this plan, alleys are straight walk-ways that have been defined by plantings of several kinds of fruit trees (“L” through “P”).

Thomas S. Sinclair, “Plan of the Pleasure Grounds and Farm of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane at Philadelphia,” in Thomas S. Kirkbride, American Journal of Insanity 4, no. 4 (April 1848): pl. opp. 280. The “Tenpin Alley” is located at “9,” above and right of “Gentlemen’s Ground.”

Associated

Frances Palmer, “Ground Plot of Brier Cottage,” in William H. Ranlett, The Architect (1849), vol. 1, pl. 2.

Frances Palmer, “A plot of village property 724 feet by 488,” in William H. Ranlett, The Architect (1849), vol. 1, pl. 48.

Attributed

George Ropes, Salem Common on Training Day, 1808.

Notes

- ↑ In American landscape writing the term “alley” was used most often in its anglicized rather than its French spelling (allée).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Manasseh Cutler, Life, Journals and Correspondence of Rev. Manasseh Cutler, LL.D., ed. William Parker Cutler and Julia Perkin Cutler, 2 vols. (Cincinnati, OH: Robert Clarke & Co., 1888), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J.-P. (Jacques-Pierre) Brissot de Warville, New Travels in the United States Performed in 1788 (New York: T. & J. Swords, 1792), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Timothy Dwight, Travels; in New-England and New-York 2 vols. (New Haven: The Author, 1821), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Lewis Beebe, Journal of Lewis Beebe, 1799–1801, vol. 3, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alexander Graydon, Memoirs of a Life Chiefly Passed in Pennsylvania within the Last Sixty Years (Harrisburg, PA: John Wyeth, 1811), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Benjamin Silliman, Remarks Made on a Short Tour between Hartford and Quebec, in the Autumn of 1819 (New Haven, CT: S. Converse, 1824), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Nathaniel Parker Willis, American Scenery, or Land, Lake and River Illustrations of Transatlantic Nature, 2 vols. (1840; repr., Barre, MA: Imprint Society, 1971), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles Mason Hovey, “Notes on Gardens and Nurseries,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 17, vol. 9 (September 1851): 410–12, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Deborah Norris Logan, The Norris House (Philadelphia: Fair-Hill Press, 1867), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Parkinson, Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris (London: Humfrey Lownes and Robert Young, 1629; repr., Norwood, NJ: W. J. Johnson, 1975), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jean de La Quintinie, The Compleat Gard’ner, or Directions for Cultivating and Right Ordering of Fruit-Gardens and Kitchen Gardens, trans. John Evelyn (1693; repr., New York: Garland, 1982), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A.-J. (Antoine Joseph) Dézallier d’Argenville, The Theory and Practice of Gardening; Wherein is Fully Handled All That Relates to Fine Gardens, . . . Containing Divers Plans, and General Dispositions of Gardens. . . , trans. John James (London: Geo. James, 1712; repr., Farnborough, England: Gregg, 1969), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Richard Bradley, New Improvements of Planting and Gardening, both Philosophical and Practical. . . , 3rd ed., 2 vols. (London: W. Mears, 1719–20), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Ephraim Chambers, Cyclopaedia, or An Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences. . . , 5th ed., 2 vols. (London: D. Midwinter et al., 1741–43), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language: In Which the Words are Deduced from the Originals and Illustrated in the Different Significations by Examples from the Best Writers, 2 vols. (London: W. Strahan for J. and P. Knapton, 1755) view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Hale, A Compleat Body of Husbandry containing rules for performing, in the most profitable manner, the whole business of the farmer and country gentleman, 2nd ed., 4 vols. (London: T. Osborne, 1758–59), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufacturers and Commerce, The Complete Farmer, or A General Dictionary of Husbandry, 2nd ed. (London: R. Baldwin et al., 1769), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Abercrombie, The Hot-House Gardener (London: J. Stockdale, 1789), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas A. Sheridan, A Complete Dictionary of the English Language, Carefully Revised and Corrected by John Andrews. . . , 5th ed. (Philadelphia: William Young, 1789) view on Zotero.

- ↑ George Gregory, A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences, 1st American ed. (Philadelphia: Isaac Peirce, 1816), view on Zotero.

- ↑ André Parmentier, “The Art of Landscape Gardening,” in The New American Gardener, ed. Thomas Fessenden (Boston: J. B. Russell, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero

- ↑ James E. Teschemacher, “On Horticultural Architecture,” Horticultural Register, and Gardener’s Magazine (November 1, 1835): 409–12, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Robert Buist, The American Flower Garden Directory, 2nd ed. (Philadelphia: Carey and Hart, 1841), view on Zotero.

- ↑ George William Johnson, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening, ed. David Landreth (Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1847), view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America. . . , 4th ed. (New York: G. P. Putnam, 1849), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William A. Ranlett, The Architect: A Series of Original Designs, for Domestic and Ornamental Cottages and Villas, Connected with Landscape Gardening, Adapted to the United States: Illustrated by Drawings of Ground Plots, Plans, Perspective Views, Elevations, Sections, and Details, 2 vols. (New York: William H. Graham et al., 1847–49), view on Zotero.