Square

See also: Bed, Common, Green, Park, Quarter

History

In landscape design vocabulary, the term square had three distinct usages derived from its definition as a geometric shape with four right angles and four equal sides. First, “square” referred to square- or rectangular-shaped beds and cultivated areas and was often used to describe the divisions within nurseries, kitchen gardens, and flower gardens. This usage was apparent in 1799 when John Latta described the flower garden at Mount Vernon, and also in 1800 when the Federal Gazette noted Adrian Valeck’s garden in Baltimore. Used in this sense, the term generally came to be subsumed under the wider terms “bed” and “plot” during the early 19th century. Second, the square represented a division of property within a city or town in a grid or orthogonal pattern, as reflected in descriptions of New Haven, Connecticut, by Manasseh Cutler (1787) and Jedidiah Morse (1789), and a report on Washington, DC, by Pierre-Charles L’Enfant (1791). J.-P. Brissot de Warville in 1788 used both senses of the term in his description of the beds in the State House Yard and the grid plan of the entire city of Philadelphia.

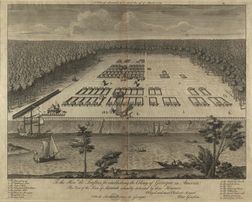

Third, and most significantly, square was used to denote a public space. An early and important example is William Penn’s 1683 plan for the city of Philadelphia, which broke from a strict grid to preserve public spaces, called squares, which would remain open for communal use. In 1734, Savannah, Georgia, was laid out with reserved open squares around which building lots were arranged [Fig. 1]. Imported from European urban planning traditions, the open square was a feature in the settlements throughout the New World. Although Spanish, French, Dutch, and German colonies designated the spaces as plaza, place d’arms, platz, and so forth, English-speaking visitors generally described these spaces as squares. They even extended application of the term to Native American settlements, as attested by William Bartram’s 1791 description of a town in Cuscowilla, Georgia (view text). Furthermore, in the English colonies, writers often used the term “square” to refer to an area that elsewhere was described as a green, yard, or common. New Haven Green, University of Virginia, and State House Yard in Philadelphia are all examples of this broader application of the term.

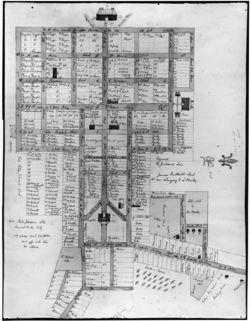

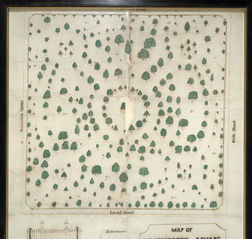

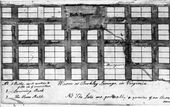

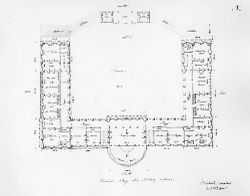

Squares marked the termination of major streets and avenues and provided visual focal points at intersections [Fig. 2].[1] Urban squares were often the setting for monuments, as in Joseph Jacques Ramée’s design for the Washington Monument in Baltimore [Fig. 3], and for public buildings, such as court houses, meeting houses, market houses, and magazines. As L’Enfant noted, the statues, columns, and obelisks that ornamented many squares not only commemorated celebrated heroes of the past, but also served as instructive examples to the present generation of proper patriotic behavior. Squares often became centers of neighborhood or civic identity, as was the case with Union Square in New York and Rittenhouse Square in Philadelphia. A 1704 resolution of the House of Burgesses of Virginia in Williamsburg suggested that the scale and openness of squares were ideally suited to position institutions of authority. As a result, squares were used as sites for civic displays, such as a parade of the Salem, Massachusetts, regiment held in 1808. Benjamin Henry Latrobe in 1800 indicated a square in his plan for a military school, a space that could be used for drilling and exercises, and that could be kept easily under surveillance [Fig. 4].

In addition to public squares, American towns occasionally included smaller residential versions of the same feature. Surrounded by private houses and intended for the recreation and enjoyment of immediate residents, these often-gated residential squares were included in the early plan of Bloomsbury Square in Annapolis, Maryland, as seen in James Stoddert’s plan of 1718 [Fig. 5]. Similar residential squares, such as Gramercy Square in New York and Louisburg Square in Boston, continued to be constructed throughout the period under study, although they never reached the popularity of their London counterparts developed after the Great Fire of 1666.[2]

Both residential and public squares provided a venue for garden or landscape design within the city. Many squares were initially grass lots, divided by walks or paths, and planted with trees in fairly simple configurations, as at New Haven Green. In the 19th century more elaborate designs became common. Benjamin Henry Latrobe’s 1819 design for Place d’Armes (renamed Jackson Square) in New Orleans [See Fig. 13], and William Rush’s 1824 plan for Franklin Public Square in Philadelphia [Fig. 6], exemplify the inclusion of intricate walks and planting beds, statuary, and ironwork fences and gates that marked these squares as ornamental—clearly intended for leisure and recreation and not as pastures for cows or drilling militia. Of particular note is the installation of fountains made possible by the introduction of pressurized water systems. These fountains set in public squares and parks became prominent symbols of civic achievement and pride.

An account of the improvements planned for Richmond’s Capitol Square in 1851 conveys the appeal of a “delightful resort” in a growing urban center, typical of mid-19th-century public landscape design projects. The attraction of these urban cases, however, went beyond aesthetics. Writers such as William A. Alcott (1838) and Louisa C. (Louisa Caroline) Tuthill (1848) argued that the healthful and moral benefits of these public spaces should be available to all classes. The opportunity that squares afforded for recreation, light, fresh air, and a mixing of the citizenry propelled these landscapes into instruments of social reform.

—Elizabeth Kryder-Reid

Texts

Usage

- Penn, William, August 16, 1683, describing Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Blome 1687: 110)[3]

- “There are also in each Quarter of the City, a Square of eight Acres to be for the like uses, as the Moor-fields in London.” [Fig. 7]

- House of Burgesses of Virginia, May 8, 1704, describing resolutions pertaining to construction in Williamsburg, VA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “The House took into consideration the report of the Committee appointed to view the Square markt out belonging to the Capitol and after some time spent therein came to these resolutions following. Resolved. That the Public Prison be included within the Bounds appropriated to the Capitol and that the said bounds already ascertained for the said Capitol be continued from the main road just before the door of One of the Capitol houses to the extent of forty one poles to the Post on the West side of the spring, thence fourteen poles to the corner of the ditch, thence along the said Ditch thirty poles and a half to a post by the said Ditch and from thence to the beginning place.” [Fig. 8]

- Ross, George, March 1, 1727, describing Newcastle, DE (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “In the middle of the Town lies a spacious green in form of a square, in a corner whereof stood formerly a Fort &c.”

- Prentis, Joseph, 1784, describing his garden in Williamsburg, VA (quoted in Lounsbury 1994: 344)[4]

- “. . . sowed Pease in the Square next Chimney. . . Glory of England, sowed same Day in Square next Street.”

- Washington, George, February 12, 1785, describing Mount Vernon, plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (Jackson and Twohig 1978: 4:89)[5]

- “Planted Eight young Pair Trees sent me by Doctr. Craik in the following places—viz.

- “2 Orange Burgamots in the No. Garden, under the back wall—3d. tree from the Green House at each end of it.

- “1 Burgamot at the Corner of the border in the South Garden just below the necessary.

- “2 St. Germians, one in each border (middle thereof) of the upper 'Square’s by the Asparagas Bed & Artichoake Ditto upper bordr.

- “3 Brown Beuries in the west square in the Second flat—viz. 1 on the border (middle thereof) next the Fall or slope—the other two an the border above the walk next the old Stone Wall.”

- Cutler, Manasseh, July 3, 1787, describing New Haven, CT, and his plans for the Ohio Company (1987: 1:218, 330–31)[6]

- “The city of New Haven covers a large piece of ground, a little descending toward the sea, with a southern aspect. It is laid out in regular square’s, with a public square' near the center. Its streets are tolerably wide, and some of them ornamented with rows of trees. There is a row of trees set round the public square, which were small while I was at college, but are now large, and add much to its beauty; a row across the center has been very lately set out, in a line with the State House, two large Meeting Houses and the Grammar School. Within the square, and on the borders of others adjoining, are six steeples and cupolas on public buildings, within a very small compass of ground.

- “You will see, by the inclosed, that our ideas of streets, and the width of front lots, nearly correspond with yours. I am not, however, pleased with the size nor form of our squares. It is proposed that there should be nine lots on a side, and four at the end, which I think will have too much of the oblong. Were the ends increased, though, I should prefer an oblong to a square; the effect would be more pleasing to the eye, and not less convenient. The rear, which I think is now too scanty, might be increased, and the whole of the lots more uniform. The plan we have formed was, unavoidably, done in a hasty manner, without drawing it on paper, and will, I think, be somewhat altered. It is our intention to set rows of mulberry trees, immediately, on each side of the streets, at the distance of ten or fifteen feet from the line on which the houses are to be built. They will make an agreeable shade, increase the salubrity of the air, add to the beauty of the streets, and, what we have principally in view, afford food for an immense number of silk-worms.”

- Brissot de Warville, J.-P., 1788, describing Philadelphia, PA (1792: 316–17)[7]

- “Behind the State-house is a public garden; it is the only one that exists in Philadelphia. It is not large; but it is agreeable, and one may breathe in it. It is composed of a number of verdant squares, intersected by alleys.

- “All the space from Front-street on the Delaware to Front-street on the Skuylkill, is already distributed into squares for streets and houses.”

- Morse, Jedidiah, 1789, describing New Haven, CT (quoted in Morse 1970: 221)

- “The town was originally laid out in squares of sixty rods. Many of these squares have been divided by cross streets. . . Near the centre of the city is the public square; on and around which are the public buildings. . .The public square is encircled with rows of trees, which render it both convenient and delightful. Its beauty, however, is greatly diminished by the burial ground, and several of the public buildings, which occupy a considerable part of it.” [Fig. 9]

- Bartram, William, 1791, describing an Indian town in Cuscowilla, GA (1928: 167–68)[8]

- “Upon our arrival we repaired to the public square or council-house, where the chiefs and senators were already convened. . .

- “The banquet succeeded; the ribs and choicest fat pieces of the bullocks, excellently well barbecued, were brought into the apartment of the public square, constructed and appointed for feasting.”

- Bentley, William, June 12, 1791, describing Pleasant Hill, seat of Joseph Barrell, Charlestown, MA (1962: 1:264)[9]

- “[June] 12. Was politely received at dinner by Mr Barrell, & family, who shewed me his large & elegant arrangements for amusement, & philosophic experiments. . . His Garden is beyond any example I have seen. . . The Squares are decorated with Marble figures as large as life. No expense is spared to render the whole amusing, instructive, & friendly.”

- L’Enfant, Pierre-Charles, August 19, 1791 and January 4, 1792, describing his plans for Washington, DC (quoted in Caemmerer 1950: 157, 165)[10]

- “The grand avenue connecting the palace and the Federal House will be magnificent. . . as also the several squares which are intended for the Judiciary Courts, the National Bank, the grand Church, the play house, markets and exchange, offering a variety of situations unparallelled for beauty, suitable for every purpose, and in every point convenient, calculated to command the highest price at a sale.

- “The Squares colored yellow, being fifteen in number, are proposed to be divided among the several States of the Union, for each of them to improve, or subscribe a sum additional to the value of the land; that purpose and the improvements around the Square to be completed in a limited time.

- “The center of each Square will admit of Statues, Columns, Obelisks, or any other ornament such as the different States may choose to erect: to perpetuate not only the memory of such individuals whose counsels or Military achievements were conspicuous in giving liberty and independence to this Country; but also those whose usefulness hath rendered them worthy of general imitation, to invite the youth of succeeding generations to tread in the paths of those sages, or heroes whom their country has thought proper to celebrate.

- “The situation of these Squares is such that they are the most advantageously and reciprocally seen from each other and as equally distributed over the whole City district, and connected by spacious avenues round the grand Federal Improvements and as contiguous to them, and at the same time as equally distant from each other, as circumstances would admit. The Settlements round those Squares must soon become connected.” [Fig. 10]

- Tucker, St. George, May 28, 1795, describing Williamsburg, VA (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “Near the center of the town there is a pleasant square of about ten acres, which is generally covered with a delightful verdure.”

- Dwight, Timothy, 1796, describing Newburyport, NH, and Boston, MA (1821: 1:439, 489–91)[11]

- “The ground, on which the former church, belonging to the same congregation [Presbyterian], stood, was purchased for $8,000; and devoted for ever to the purpose of enlarging a small public square. . .

- “A handsome lot has been purchased by Moses Brown, Esq. in front of one of the churches, for $13,000; and appropriated for ever, as an open square, to the use of the public; an act of liberality, which needs no comment.

- “Boston contains one hundred and thirty-five streets, twenty-one lanes, eighteen courts, and, it is said, a few squares: although, I confess, I have never seen any thing in it, to which I should give that name. . .

- “It is remarkable, that the scheme of forming public squares, so beautiful, and in great towns so conducive to health, should have been almost universally forgotten. Nothing is so cheerful, so delightful, or so susceptible of the combined elegancies of nature and art. On these open grounds the inhabitants might always find sweet air, charming walks, fountains refreshing the atmosphere, trees excluding the sun, and, together with fine flowering shrubs, presenting to the eye the most ornamental objects, found in the country. Here, also, youth and little children might enjoy those sports, those voluntary indulgences, which in fresh air, are, peculiarly to them, the sources of health and the prolongation of life. Yet many large cities are utterly destitute of these appendages; and in no city are they so numerous, as the taste for beauty, and a regard for health, compel us to wish.”

- Latta, John, 1799, describing Mount Vernon, plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (quoted in Martin 1991: 143)[12]

- “The garden is very handsomely laid out in squares and flower knots and contains a great variety of trees, flowers and plants of foreign growth collected from almost every part of the world.”

- Beebe, Lewis, 1800, describing a Mr. Pratt’s garden (exact location undetermined) (Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Journal of Beebe Lewis, 1799–1801)[13]

- “Likewise the border of every square is impossible for me to describe. The remaining parts of each square within the border, is planted with beans, pease, cabbage, onions, Betes, carrots, Parsnips, Lettuse, Radished, Strawberries, cucumbers, Potatoes, and many other articles.”

- Anonymous, June 14, 1800, describing in the Federal Gazette the estate of Adrian Valeck, Baltimore, MD (quoted in Sarudy 1989: 136)[14]

- “A large garden in the highest state of cultivation, laid out in numerous and convenient walks and squares bordered with espaliers, on which. . . the greatest variety of fruit trees, the choicest fruits from the best nurseries in this country and Europe have been attentively and successfully cultivated. . . Behind the garden in a grove and shrubbery or bosquet planted with a great variety of the finest forest trees, oderiferous & other flowering shrubs etc.”

- Scott, Joseph, 1806, describing Centre Square, Philadelphia, PA (1806: 25–26)[15]

- “The water-works of Philadelphia are the most extensive of their kind of any in America. . . The water is discharged into a circular aqueduct, extending along Chestnut and Broad streets, into the middle of Market-street, in the centre square. . . In the centre square, upon Market-street, is a marble edifice, which receives the water from Schuylkill. It also contains a steam engine, which raises the water to a reservoir, whence it descends into wooden pipes, which convey it through the city. The building in the centre square, is a square of sixty feet, with a Doric portico on the east and west fronts.” [Fig. 11]

- Anonymous, October 15, 1808, describing Salem, MA (Essex Register)

- “On Wednesday last the Salem Regiment, the Cadets, the Artillery and the Cavalry, formed a line on Washington Square, and were inspectedand reviewed by the proper officers. The appearance of the whole line was highly gratifying to the spectators. In the afternoon the imitation of battle was performed with spirit and precision; and very much to the satisfaction of the military men.” [Fig. 12]

- Ramsay, David, 1809, describing Charleston, SC (1858: 128)[16]

- “About the year 1755 Henry Laurens purchased a lot of four acres in Ansonborough, which is now called Laurens’s square, and enriched it with everything useful and ornamental that Carolina produced or his extensive mercantile connections enabled him to procure from remote parts of the world. Among a variety of other curious productions, he introduced olives, capers, limes, ginger, guinea grass, the alpine strawberry, bearing nine months in the year, red raspberrys, blue grapes; and also directly from the south of France, apples, pears, and plums of fine kinds, and vines which bore abundantly of the choice white eating grape called Chasselates blancs. The whole was superintended with maternal care by Mrs. Elinor Laurens with the assistance of John Watson, a complete English gardener.”

- Martin, William Dickinson, May 21, 1809, describing Princeton, NJ (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “In front of it [the College] is a very handsome green square of about four Acres, enclosed in a railing, & produces very fine herbage. It is attached to the College as a place of recreation & amusement for the students.”

- Proceedings of the Corporation, December 10, 1810, describing the Elgin Botanic Garden, New York, NY (quoted in Hosack 1811: 51)[17]

- “that so long as the said grounds are continued as a botanic garden, or as an open square for any other public use, the streets intersecting the same will not be required to be opened.”

- Anonymous, 1815, describing in the Georgia Journal the improvements of the state capitol in Milledgeville, GA (quoted in Lounsbury 1994: 292)[4]

- “[Improvements included] the enclosure of the State-House square and avenues of trees planted in it, which in a few years will form an agreeable and beautiful prominade [sic].”

- Anonymous, 1817, describing Savannah, GA (quoted in Schwaab and Bull 1973: 144)[18]

- “Squares to the amount of 14 or 16 are judiciously interspersed through the town, relieving the monotony resulting from streets crossing each other at right angles, as those of this city do. Circular enclosures surround the centres of those squares, which together with the side walks, are planted with a number of similar ornamental trees.”

- Anonymous, October 10, 1817, describing Richmond, VA (Richmond Enquirer)

- “It was but in February, 1816, that the Act passed 'Establishing a Museum on part of the Public Square, in the city of Richmond.' . . . And lo! the building is completed—an ornament to the Public Square, and an ornament to the State which contains it.”

- Latrobe, Benjamin Henry, January 13, 1819, describing New Orleans, LA (1951: 23)[19]

- “The public square, which is open to the river, has an admirable general effect, & is infinitely superior to anything in our Atlantic cities as a water view of the city. This square extends along the river about—feet, and is—feet deep. The whole of the side parallel to the river is occupied by the Cathedral in the center & by two symmetrical buildings on each side. That to the West is called the Principal, & contains the public offices & council chamber of the city. That on the East is called the Presbytery, being the property of the Church.” [Fig. 13]

- New Orleans City Council, January 16, 1819 (Howard-Tilton Memorial Library, Tulane University)

- “the Mayor is authorized to have as many young willow trees planted along the length of the City Levee as he deems necessary, and to have a protection placed around them as to insure their growth; That the Mayor is furthermore authorized to have other trees planted in the Public Square to take the place of those that are missing.”

- Anonymous, 1820, describing Memphis, TN (quoted in Schwaab 1973: 179)[18]

- “The streets run to the cardinal points. They are wide and spacious, and, together with a number of alleys, afford a free and abundant circulation of air. There are, besides, four public squares, in different parts of the town, and between the front lots and the river, is an ample vacant space, reserved as a promenade; all of which must contribute very much to the health and comfort of the place, as well as to its security and ornament.”

- Anonymous, May 26, 1824, describing the Columbian Institute, Washington, DC (quoted in O’Malley 1989: 132)[20]

- “1st. The water of Tiber Creek being thus conducted into the Capitol square, will afford ample security against the progress of fire.”

- Forman, Martha Ogle, August 20, 1824, describing Newark, NJ (1976: 185)[21]

- “Newark is a very pretty little Village. I was pleased with its fine Churches, and wide streets, and its large squares of Grass, with its neat white houses and little yards in front filled with shrubbery.”

- Trollope, Frances Milton, 1830, describing Washington Square, Philadelphia, PA (1832: 2:48–49)[22]

- “Near this enclosure [at the State House] is another of much the same description, called Washington Square. Here there was an excellent crop of clover; but as the trees are numerous, and highly beautiful, and several commodious seats are placed beneath their shade, it is, spite of the long grass, a very agreeable retreat from heat and dust. It was rarely, however, that I saw any of these seats occupied; the Americans have either no leisure, or no inclination for those moments of delassement that all other people, I believe, indulge in. . . it is nevertheless the nearest approach to a London square that is to be found in Philadelphia.” [Fig. 14]

- Bryant, William Cullen, August 23, 1832, describing Jacksonville, IL (1975: 357)[23]

- “The village of Jacksonville is a remarkably moral place—more so than most villages in New England, and the people seem intelligent. It is a collection of mean little houses about a dirty square, and is one of the ugliest and most unpleasant places I ever saw. It stands in the midst of a prairie and is without a tree, except some very little ones just planted—but these are not on the principal square.”

- Ingraham, Joseph Holt, 1835, describing a plantation near New Orleans, LA (1835: 1:81–82)[24]

- “On the left and diagonally from the dwelling house we noticed a very neat, pretty village, containing about forty small snow-white cottages, all precisely alike, built around a pleasant square, in the centre of which, was a grove or cluster of magnificent sycamores. Near by, suspended from a belfry, was the bell which called the slaves to and from their work and meals. This village was their residence, and under the shade of the trees in the centre of the square, we could discern troops of little ebony urchins from the age of eight years downward, all too young to work in the field, at their play. . .” [Fig. 15]

- Ingraham, Joseph Holt, 1835, describing New Orleans, LA (1835: 1:91)[24]

- “Though the water, or shore-line, is very nearly semi-circular, the Levée-street, above mentioned, does not closely follow the shore, but is broken into two angles, from which the streets diverge as before mentioned. These streets are again intersected by others running parallel with the Levée-street, dividing the city into squares, except where the perpendicular streets meet the angles, where necessarily the ‘squares’ are lessened in breadth at the extremity nearest the river, and occasionally form pentagons and parallelograms, with oblique sides, if I may so express it.

- “After crossing Levée-street, we entered Rue St. Pierre, which issues from it south of the grand square. This square is an open green, surrounded by a lofty iron railing, within which troops of boys, whose sports carried my thoughts away to ‘home sweet home,’ were playing, shouting and merry making.”

- Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), November 1839, “Notices of Gardens and Horticulture, in Salem, Mass.,” describing Elias Hasket Derby House, Salem, MA (Magazine of Horticulture 5: 410–11)[25]

- “The extent of the garden and pleasure ground is several acres. The garden lies to the south of the mansion, and is, we should judge, nearly a square. It is laid out with straight walks, running at right angles, with flower borders on each side of the alleys, and the squares occupied by fruit trees; the green-house and grapery stand in the centre of the garden, and are screened on the back by a hedge.”

- Buckingham, James Silk, 1841, describing New York, NY (1841: 1:38–39)[26]

- “Of the public places for air and exercise with which the Continental cities of Europe are so abundantly and agreeably furnished, and which London, Bath, and some other of the larger cities of England contain, there is a marked deficiency in New-York. Except the Battery, which is agreeable only in summer—the Bowling Green is a confined space of 200 feet long by 150 broad; the Park, which is a comparatively small spot of land (about ten acres only) in the heart of the city, and quite a public thoroughfare; Hudson Square, the prettiest of the whole, but small, being only about four acres; and the open space within Washington Square, about nine acres, which is not yet furnished with gravel-walks or shady trees—there is no large place in the nature of a park, or public garden, or public walk, where persons of all classes may take air and exercise. This is a defect which, it is hoped, will ere long be remedied, as there is no country, perhaps, in which it would be more advantageous to the health and pleasure of the community than this to encourage, by every possible means, the use of air and exercise to a much greater extent than either is at present enjoyed.” [Fig. 16]

- Mills, Robert, February 23?, 1841, describing his design for the national Mall, Washington, DC (Scott 1990: n.p.)[27]

- “A range of trees is proposed to surround three sides of the square which is intended to be laid open by an iron or other railing, the north side to be enclosed with a high brick wall to serve as a shelter and to secure the various hot houses and other buildings of an inferior character.” [Fig. 17]

- Trego, Charles, 1843, describing Philadelphia, PA (1843: 318–19)[28]

- “Public Squares.—It is to the wise and liberal foresight of the great founder of Pennsylvania that we owe most of the public squares which now ornament our city. In the original plan, as laid out by Thomas Holmes, Penn’s surveyor general in 1682, there was to be a public square in the centre containing ten acres, and one in each quarter of the city containing eight acres. . .

- “Washington square, on Sixth street between Walnut and Locust, was for many years used as a public burial ground for the poor and for strangers, under the name of the Potters’ field. . . Its improvement as a public square commenced in 1815, when a variety of trees were planted, gravel walks laid out, and other steps taken which have led to its present attractive appearance. It is intended to erect, in the centre of this square,a monument to the memory of Washington; the cornerstone having been laid with due ceremony at the celebration of his birth day, on the 22nd of February, 1833.

- “Franklin square is on Sixth street between Race and Vine, being also laid out with gravel walks and planted with trees, affording a public promenade equally agreeable with Washington square. A magnificent fountain, surrounded by a marble basin, has been constructed in the centre, supplied with water from the works at Fairmount.

- “Logan square. . . and Rittenhouse square. . . are both enclosed and planted with trees, and promise in a few years to present an appearance similar to Washington and Franklin squares, affording to the inhabitants of the western part of the city, cool and shady walks of equal attraction to those now enjoyed in the eastern squares.

- “Penn square, at the intersection of Market and Broad streets, was, within the recollection of many now living, not a square but a circle, having the street passing round it and enclosing the distributing reservoir of the city water works.”

- Bryant, William Cullen, April 7, 1843, describing Savannah, GA (Clarke 1993: 2:154)[29]

- “Savannah is beautifully laid out; its broad streets are thickly planted with the Pride of India, and its frequent open squares shaded with trees of various kinds.”

- Barber, John Warner, 1844, describing Pittsfield, MA (1844: 87–88)[30]

- “There is a public square in the center, containing about four acres: in the center of this square is a large elm, which was left standing when the original forest was cleared away.” [Fig. 18]

- Tuthill, Louisa C. (Louisa Caroline), 1848, describing the public squares in New York, NY, and Philadelphia, PA (1848: 317, 319)[31]

- “The citizens of New York have at length become aware of the beauty and salubrity of public squares. St. John’s Park, Washington Square, Union Square, and several others in recently-built parts of the city, are tastefully ornamented with trees and shrubbery, affording sweet green spots for the eye to rest upon, as a relief from the glare of brick walls and dirty pavements.

- “The public squares of Philadelphia, are incalculably important to the health of the city. Beneath the dense foliage of Washington Square, crowds of merry children enjoy, unmolested, their healthful sports. Within the enclosure of Independence Square, was first promulgated the Declaration of Independence. Franklin Square has in the centre a fountain, falling into a handsome, white marble basin. Penn, Logan, and Rittenhouse Squares are also ornamental to the city.”

- Town Council of the Borough of West Chester, March 13, 1848, describing West Chester, PA (quoted in Darlington 1849: 492–93)[32]

- “Whereas it has been deemed expedient and proper to improve the public Square, on which the upper reservoir connected with the Waterworks of the borough is situated, by laying out the same in suitable walks, and introducing various ornamental trees and shrubbery: And whereas it will be convenient and necessary to designate the said Square by some appropriate name: . . . That the public Square, aforesaid, shall for ever hereafter be designated and known by the name of ‘THE MARSHALL SQUARE.’”

- Committee on the Capitol Square, Richmond City Council, July 24, 1851, describing John Notman’s plans for the Capitol Square, Richmond, VA (quoted in Greiff 1979: 162)[33]

- “It was deemed advisable to commence the improvements of the Square itself on the western side thereof. . . the ground on that side [has been] formed into gentle natural undulations, rising gradually to the base of the capitol and to the monument. . . giving great apparent extent to the grounds and producing an agreeable variety and at the same time affording space for much greater extent of walks, leading in every direction where they may be useful or agreeable without the necessity of climbing steps and dividing the grounds into irregular and picturesque lawns. . .

- “The eastern portion of the square will likewise undergo considerable change—the rugged features will be materially softened down, a fountain and jet d’eau to correspond with those on the western side will be placed in the valley near the state courthouse. . .

- “The most beautiful feature of the contemplated alterations of the Square, however, will be found in the arrangement of the trees and shrubbery. Instead of planting these in parallel rows, like an ordinary orchard some attention will be paid to landscape gardening—groves, arbours, parterres, and fountains will combine to render the Square a place of delightful resort.”

Citations

- Parkinson, John, 1629, Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris (1629; repr., 1975: 5)[34]

- “To forme it [the garden] therfore with walks, crosse the middle both waies, and round about it also with hedges, with squares, knots and trayles, or any other worke within the foure square parts, is according as every mans conceit alloweth of it, and they will be at the charge.”

- Chambers, Ephraim, 1743, Cyclopaedia (1743: 2:n.p.)[35]

- “PIAZZA, in building, popularly called piache, an Italian name for a portico, or covered walk, supported by arches. See PORTICO.

- “The word literally signifies a broad open place or square; whence it also became applied to the walks or portico’s around them.”

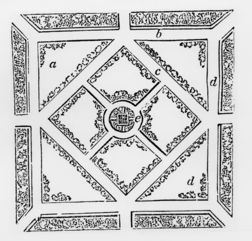

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826: 1029–30)[36]

- “7319. Public squares, of such magnitude as to admit of being laid out in ample walks, open and shady, are almost peculiar to Britain. The grand object is to get as extended a line of uninterrupted promenade as is possible within the given limits. A walk parallel to the boundary fence, and at a short distance within it, evidently includes the maximum of extent; but if the enclosure is small, the rapid succession of angles and turns becomes extremely disagreeable, and continually breaks in upon the pas des promeneurs, the conversation of a party, or individual contemplation. The angles, therefore, must be avoided, by rounding them off in a large square; in a small one, by forming the walk into a circle; and in a small parallelogram, by adopting an oval form. In laying out a large square. . . four objects ought to be kept in view. 1. Sufficient open space (a), both of lawn and walk, so as the parents, looking from the windows of the houses which surround the square, may not long at a time lose sight of their children: 2. An open walk, exposed to the sun, for winter and spring (b): 3. A walk shaded by trees, but airy for summer (c): 4. Resting-places (d); and a centrical covered seat and retreat (e), which, being nearly equidistant from every point may be readily gained in case of a sudden shower, &c. The statues of eminent public men are obvious and appropriate decorations for squares.” [Fig. 19]

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828: 2:n.p.)[37]

- “SQUARE, n. . .

- “2. An area of four sides, with houses on each side.

- “The statue of Alexander VII. stands in the large square of the town. Addison.”

- Bridgeman, Thomas, 1832, The Young Gardener’s Assistant (1832: 1)[38]

- “the centre part of the garden may be divided into squares, on the sides of which a border may be laid out three or four feet wide, in which the various flowering plants may be raised, unless a separate flower garden is intended. The centre beds, may be planted with all the various kinds of vegetables as well as Gooseberries, Currants, Raspberries, Strawberries, &c.”

- Anonymous, April 1, 1837, “Landscape Gardening” (Horticultural Register 3: 129)[39]

- “Fountains are going out of use, though we think without sufficient reason. In more frequented grounds, such as public squares in towns, we think them particularly appropriate. We would not, however, propose even for these, such expensive fountains as are frequently seen in Europe, where water is poured forth in immense volumes in marble basins, amid tritons and sea horses, and cars. A single streak of water would be a more pleasing object.”

- Alcott, William A., 1838, “Embellishment and Improvement of Towns and Villages” (American Annals of Education 8: 337–42)[40]

- “Of our larger cities, even Philadelphia and Boston, we do not hesitate to say that almost every thing, in their structure and condition, is at war with the highest physical and moral well being of their inhabitants. We do not indeed forget their beautiful commons and squares and public walks; but it is impossible for us to believe that a few of these will ever atone for that neglect whose effects stare us in the face, not merely in passing through dirty and filthy avenues, but in traversing almost every street, and in turning almost every corner. A single common, beautiful though it may be, as any spot on the earth’s surface, and refreshed though it were by the balmy breezes which 'blow soft o’er Ceylon’s isle;' or a few public squares, remembrancers though they be of him whose praises will never cease to be celebrated while the 'city of brotherly love' shall remain, will yet never purify the crowded, unventilated cellars and shops—and dwellings, too—of a hundred or a thousand thickly congregated streets. . .

- “We wish to see not only spacious squares or commons interspersed with shade, if not with fruit trees, in every village and town and city, but we wish to see public gardens on an extensive scale. We wish to see these not only for health’s sake, and for the sake of their moral tone and tendency, but as a means of rational amusement—as a means of promoting the public cheerfulness, the public taste, and of consequence, the public happiness.”

- Sayers, Edward, June 1, 1838, “The Kitchen Garden” (Horticultural Register 4: 235)[41]

- “In laying a Kitchen Garden out, it should be done in the most simple manner, both for convenience, and a correspondence of its utility. The most approved method is to have the garden so situated as to be in a square with the four points of the compass, viz: N. S. E. W., surrounded with either a boarded fence or brick wall. The ground will require to be divided into four or six squares, according to its size, if no more than an acre or two, four will be sufficient; if larger, six will be requisite.”

- Tuthill, Louisa C. (Louisa Caroline), 1848, History of Architecture (1848: 317–20)[31]

- “Every city should make ample provision for spacious public squares. Trees of every variety, shrubs, flowers, and evergreens, should decorate these grounds, and fountains throw up their sparkling waters, contrasting their pure, white marble with the deep green foliage. Here, beneath the shaded walks, the inhabitants might enjoy the sweet air, the children sport upon the fresh grass, and all be refreshed and cheered by the sight of beautiful natural objects. Here the young and the old might meet to ‘drive dull care away,’ and lose for a few brief moments the calculating, moneymaking plans that almost constantly usurp American thought and feeling. . .

- “Gardens and squares are so necessary to the health, as well as the enjoyment of those who are shut up in the close streets of a city, that it should be considered an imperative duty to provide them for all classes of the inhabitants. It may be urged, that if left open and free, the decorations would soon be destroyed by the populace; some few rude hands might occasionally make sad havoc among them, but when the people had once learnt how much such places of resort contributed to their health and pleasure, they would carefully protect them from injury.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1849, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849; repr., 1991: 154, 161, 231)[42]

- “It [the White American Elm] is one of the most generally esteemed of our native trees for ornamental purposes, and is as great a favorite here as in Europe for planting in public squares and along the highways. Beautiful specimens may be seen in Cambridge, MA, and very fine avenues of this tree are growing with great luxuriance in and about New Haven. . .

- “In avenues it [the plane tree] is often happily employed, and produces a grand effect. It also grows with great vigor in close cities, as some superb specimens in the square of the Statehouse, Pennsylvania Hospital, and other places in Philadelphia fully attest. . .

- “In New York and Philadelphia, the Ailantus is more generally known by the name of the Celestial tree, and is much planted in the streets and public squares.”

Images

Inscribed

Samuel Vaughan, “Warm or Berkeley Springs, in Virginia,” 1787, from the diary of Samuel Vaughan, June–September 1787.

William Bartram, “Arrangement of the Chunky-Yard, Public Square, and Rotunda of the modern Creek towns,” in “Observations on the Creek and Cherokee Indians” (1789), from Transactions of the American Ethnological Society 3, part 1 (1853): 54, fig. 3.

William Bartram, Plan of a Cherokee Private “Habitation,” in “Observations on the Creek and Cherokee Indians” (1789), from Transactions of the American Ethnological Society 3, part 1 (1853): 56, fig. 5.

William Bartram, “Plan of the Ancient Chunky-Yard,” in “Observations on the Creek and Cherokee Indians” (1789), from Transactions of the American Ethnological Society 3, part 1 (1853): 52, fig. 2.

Pierre-Charles L’Enfant, “Plan of the City intended for the Permanent Seat of the Government of the United States. . . ,” August 1791.

Lewis Miller, “The Light Horseman,” 1799.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Military academy. Principal story, floor plan, 1800.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, “Project for the Principal Gates of the Public Square at New Orleans,” c. March 1819.

J. C. Loudon, Plan of a large public square, in An Encyclopædia of Gardening, 4th ed. (1826), 1030, fig. 733.

Associated

Alexander Jackson Davis, Ithiel Town, and James Dakin, New York University, Washington Square, 1833.

Robert Mills, Alternative plan for the grounds of the National Institution, 1841.

Frances Palmer (artist), Nathaniel Currier (lithographer), “Union Place Hotel, Union Square New-York,” c. 1845.

Attributed

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, “Plan of the public Square in the city of New Orleans, as proposed to be improved. . .” [detail], March 20, 1819.

Anne-Marguerite-Henriette Rouillé de Marigny Hyde de Neuville, Washington City, 1821.

Notes

- ↑ For an in-depth treatment of early American squares, see John W. Reps, The Making of Urban America: A History of City Planning in the United States (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1965), view on Zotero, and Carl Feiss, “Early American Public Squares,” in Town and Square, from the Agora to the Village: Instruments of Social Reform, ed. Paul Zucker (New York: Columbia University Press, 1959), 237–55, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Feiss, “Early American Public Squares,” 245, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Richard Blome, The Present State of His Majesties Isles and Territories in America (London: H. Clark, 1687), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Carl R. Lounsbury, ed., An Illustrated Glossary of Early Southern Architecture and Landscape (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), view on Zorero.

- ↑ George Washington, The Diaries of George Washington, ed. Donald Jackson and Dorothy Twohig, 6 vols. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1976-79), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Parker Cutler, Life, Journals, and Correspondence of Rev. Manasseh Cutler, LL.D. (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1987), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J.-P. (Jacques-Pierre) Brissot de Warville, New Travels in the United States of America, Performed in 1788, ed. Durand Echeverria, trans. Maro S. Vamos and Durand Echeverria (Cambridge, MA: Belknap, 1964), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Bartram, Travels through North and South Carolina, Georgia, East and West Florida, ed. Mark Van Doren (New York: Dover, 1928), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Bentley, The Diary of William Bentley, D.D., Pastor of the East Church, Salem, Massachusetts (Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1962), view on Zotero.

- ↑ H. Paul Caemmerer, The Life of Pierre-Charles L’Enfant, Planner of the City Beautiful, The City of Washington (Washington, DC: National Republic Publishing Company, 1950), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Timothy Dwight, Travels; in New-England and New-York, 4 vols. (New Haven: The Author, 1821–22), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Peter Martin, The Pleasure Gardens of Virginia: From Jamestown to Jefferson (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Lewis Beebe, Lewis Beebe Journal, 1776–1801, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Barbara Wells Sarudy, “Eighteenth-Century Gardens of the Chesapeake,” Journal of Garden History 9 (1989): 104–59, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Joseph A. Scott, Geographical Description of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia: Printed by R. Cochran, 1806), view on Zotero..

- ↑ David Ramsay, Ramsay’s History of South Carolina, from Its First Settlement in 1670 to the Year 1808 (Newberry, SC: W. J. Duffie, 1858), view on Zotero.

- ↑ David A. Hosack, Statement of Facts Relative to the Establishment and Progress of the Elgin Botanic Garden (New York: C. S. Van Winkle, 1811), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Eugene L. Schwaab and Jacqueline Bull, Travels in the Old South (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1973), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Impressions Respecting New Orleans: Diaries and Sketches, 1818–1820, ed. Samuel Wilson (New York: Columbia University Press, 1951), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Therese O’Malley, “Art and Science in American Landscape Architecture: The National Mall, Washington, D.C., 1791–1852” (PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1989), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Martha Ogle Forman, Plantation Life at Rose Hill: The Diaries of Martha Ogle Forman, 1814–1845 (Wilmington: Historical Society of Delaware, 1976), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Frances Trollope, Domestic Manners of the Americans, 3rd ed., 2 vols. (London: Wittaker, Treacher, 1832), view on Zotero..

- ↑ William Cullen Bryant, The Letters of William Cullen Bryant, ed. William Cullen Bryant II and Thomas G. Voss (New York: Fordham University Press, 1975), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Joseph Holt Ingraham, The South-West, 2 vols. (New York: Harper, 1835), view on Zotero.

- ↑ C. M. Hovey, “Notices of Gardens and Horticulture, in Salem, Mass.,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 5, no. 11 (November 1839): 401–16, view on Zotero.

- ↑ James Silk Buckingham, America, Historical, Statistic, and Descriptive, 2 vols. (New York: Harper, 1841), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Pamela Scott, ed., The Papers of Robert Mills (Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Resources, 1990), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Charles B. Trego, A Geography of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia: Edward C. Biddle, 1843), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Graham Clarke, ed., The American Landscape: Literary Sources and Documents, 3 vols. (East Sussex, England: Helm Information, 1993), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Warner Barber, Historical Collections, Being a General Collection of Interesting Facts, Traditions, Biographical Sketches, Anecdotes, &c., Relating to the History and Antiquities of Every Town in Massachusetts, with Geographical Descriptions (Worcester, MA: Warren Lazell, 1844), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Louisa C. Tuthill, History of Architecture, from the Earliest Times; Its Present Condition in Europe and the United States; with a Biography of Eminent Architects, and a Glossary of Architectural Terms, by Mrs. L. C. Tuthill (Philadelphia: Lindsay and Blakiston, 1848), view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Darlington, Memorials of John Bartram and Humphry Marshall: With Notices of Their Botanical Contemporaries (Philadelphia: Lindsay & Blakiston, 1849), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Constance Greiff, John Notman, Architect, 1810–1865 (Philadelphia: Athenaeum of Philadelphia, 1979), view on Zotero.

- ↑ John Parkinson, Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris (1629; repr., Norwood, NJ: W.J. Johnson, 1975), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Ephraim Chambers, Cyclopaedia, or An Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences. . . , 5th ed., 2 vols. (London: D. Midwinter et al., 1741–43), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, 4th ed. (London: Longman et al., 1826), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Bridgeman, The Young Gardener’s Assistant, 3rd ed. (New York: Geo. Robertson, 1832), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, “Landscape Gardening,” Horticultural Register, and Gardener’s Magazine 3 (April 1, 1837): 121–31, view on Zotero.

- ↑ William A. Alcott, “Embellishment and Improvement of Towns and Villages,” American Annals of Education 8, no. 8 (August 1838): 337–47, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Edward Sayers, “The Kitchen Garden,” Horticultural Register, and Gardener’s Magazine 4 (June 1, 1838): 235–37, view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America, 4th ed. (1849; repr., Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1991), view on Zotero.